12

Readiness to Act: Leadership and Scaling a New Venture

As the Superintendent of Denver Public Schools, Tom Boasberg wanted to go beyond conventional approaches to solving the problem of underachievement in the city's schools. Like many American cities, Denver had a long history of racial and socioeconomic disparity across school districts. Efforts to improve performance had generated mixed results. Anxious to find a way to help students get a better education, Boasberg adopted an ambidextrous approach. One part of the organization, led by Chief of Schools Susana Cordova, pursued the traditional educational model. A teacher spoke to a classroom full of students, who listened, answered questions, took notes, and then did homework assignments to reinforce what they had learned. Then, he created a separate group to develop experiments to test new pedagogical approaches. His Corporate Explorer was Alyssa Whitehead-Bust, chief innovation officer for Denver schools and leader of the “Imaginarium,” a unit charged with focus on reinventing schooling.1

This was a bold effort to reinvent teaching by helping schools both improve their current teaching and learning methods as well as developing fundamentally different teaching and learning methods (at that time, blended and personalized learning). These new teaching models gave more freedom to students to direct their own learning. They experimented with techniques like “flipping the classroom.” This involved students watching traditional educational content online and then doing homework assignments in class when the teacher was there to help. The Imaginarium was a conscious attempt to experiment with new learning models. It freed schools from traditional teaching norms, positioning teachers as facilitators, rather than a “sage on the stage.”

Despite generating promising results, the Imaginarium was controversial. Teachers were concerned about losing their traditional professional identity. They had trained to perform in one model, now Boasberg and Whitehead-Bust were upending that role. Also, parents were uncomfortable with children being used for pedagogical experiments. They wanted better results for their children but were suspicious about the Imaginarium's unproven approach. Finally, even though there was excitement in the Denver Public Schools Vision for 2020, there was mixed enthusiasm in Boasberg's leadership team on when to scale these new teaching approaches.

Boasberg's innovation was at a critical point, he had to decide how far he would take the new Imaginarium model. His team had created a concept for a new approach to education, won support for funding from the school board and city and state authorities, and now it was time to bring it to scale. Could he get parents, teachers, and his extended leadership team on board with the new approach and demonstrate how innovation could transform educational outcomes in Denver? It was at this moment, that Boasberg went on a six-month sabbatical. He placed Cordova in charge as his temporary replacement. When Boasberg returned, the Imaginarium was effectively gone.2 Faced with budget cuts from the city and a painful teacher's strike, Cordova cut its budget and it closed a year later. She applied the logic of the core business and defended the conventional approach. Even when the data suggested that the new, decentralized teaching methods improved student outcomes, it was hard for these experiments to survive. When it came time to make a decision to scale the Immaginarium's learnings, Boasberg and his team stepped back. Core had beaten explore.

Competing Commitments

Boasberg originated the Imaginarium strategy, and when the going got tough he avoided the battle ahead. He was not ready to commit to the innovation when the stakes were high. Boasberg is not alone in stumbling at this point in the journey. A similar story is repeated in different guises by leaders in organizations large and small, private, and public, for profit and not-for-profit. Leaders faced with the opportunity to commit to a new technology or business model that could enable them to lead disruption often choose a path of safety. Instead of committing resources to scale a new venture, they withdraw, preferring to lament the failure of the innovation (and innovators) than publicly commit to its success.

Innovation is exciting and safe when it starts, harder when it means making a decision that involves sacrificing something about the present. Ideation has only positive consequences for leaders. Employees engage their imaginations and enjoy the near-addictive experience of generating new ideas. The outcomes are usually incremental improvements to what you already have today; occasionally a brilliant idea emerges, and it moves to incubation. This requires more resources and there is some expectation that something good will come from the effort. However, incubation requires modest resources and can be done at a safe distance from the core business, so consequences remain relatively low. Scaling is when the stakes get high.

As an aspiring Corporate Explorer, it can be demoralizing when a company backs away from innovation, unwilling to put resources at risk on an unproven new business or initiative. It confirms our assumptions about a short-term focus, risk aversion, and concern for the judgment of the financial markets. However, most leaders, including Boasberg, are deeply committed to the success of new ventures. Their challenge is that they have another, competing commitment that usually wins. This is a commitment to sustaining the performance of their current business or organization. As the scale of commitment to a new venture increases, this competition intensifies. It is always hard for innovation to win this head-to-head because, no matter how well incubated, it only has an indication of future potential, not a guarantee. Managers code the risk of an immediate hit to short-term performance as a higher priority than converting long-term opportunity or avoiding the potential to be disrupted by a new entrant.

This is the reason we struggle making the decision to scale a venture. We have competing commitments – one to stability and one to innovation.3 Leaders that commit to new ventures, without being forced into it by a performance crisis, are fighting against the forces of human psychology and organizational culture. We want to avoid loss and minimize risk.

How do we create the readiness to act? Our recommendation is that Corporate Explorers work hard to replace the question, “Do we have either stability or innovation” with “How do we have both stability and innovation?” This reframing of the competing commitments as a both/and leadership challenge is more than a linguistic trick. It opens new solutions that can unlock ways of meeting both commitments without making compromises that purport to support innovation, but really sustain the status quo. We have found that this reframing requires a senior leadership team that can have honest and open dialogue about why meeting both commitments is difficult and what it means to the core business. Doing this relies on an ability to maintain productive tension in the senior team, where it is possible to address tough issues with objectivity. The Corporate Explorer may need to develop some techniques for holding up a mirror to the CEO and senior team to raise constructive tension. This is not simple, but it is a powerful way to intervene and help senior leadership work out how to sustain their commitments.

Reframing the competing commitments as a both/and problem takes you to the point of action. We still need a leader with the courage to commit. This is a necessary, if not sufficient condition, for the success of the Corporate Explorer. It may seem frustrating given our focus on rigorous, data-driven methods, that success should hang on the predisposition of a leader; however, it turns out that leadership matters. Someone needs to be ready to make the decision to take an opportunity from incubation to scale.

Both/And Leadership

The key first step to managing the competing commitments between core and explore is to admit that the tension exists. Transparency about the tension between core and explore helps to make issues discussable and resolvable. Early in the life of a new venture it may seem like a sour note. Expectations are high, there is ambition and excitement about the possibilities a new set of experiments will bring. However, the longer the tension is denied, the harder it becomes to address. The alternative is to “fudge it” by finding a way to compromise between the two commitments. That means the commitment to the core business wins by default. Reframing as a both/and problem can open a different set of options (see Table 12.1). We will explain this with a real-life example.4

Anna is the founder CEO of a business-to-business technology company.5 Her firm grew rapidly over the past decade and now has more than $1 billion in revenue. The firm has loyal customers that adopted the company's solution early on, helping to fuel its meteoric rise. Now, Anna worries about sustaining the pace of growth, especially after the company goes public. Many new areas of opportunity are emerging as their market matures; even so the pace of technological change is high and new entrants are emerging to threaten their markets. Developing these opportunities means leveraging the same technology base that serves the core market, threatening to pull key software engineers away from work for existing customers. Anna fears that serving new markets would divert key technical and sales resources away from the customer base that had served her so well.

Anna resolved her competing commitment by setting up new ventures to build solutions for a new market, but with the existing sales organization providing the go-to-market capability. This way, she reasoned, the sales team could ensure current customers did not suffer any negative impacts from the push into new markets. The commitment to customers undermined the commitment to new engines of growth. This compromise strategy diminishes both commitments. It makes it difficult for the new venture to succeed, yet still consumes the time, resources, and attention of the core business.

Anna adopted an either/or problem-solving strategy that put the commitment to the core ahead of the explore. Anna was framing the problem as either they pursued innovation in new markets, or they secured the needs of current customers. It was a false dichotomy. An alternative problem-solving strategy is to reframe this as a both/and question. We worked with her to reframe the opportunity to serve new markets as a both/and strategy. There are five steps to this approach:

- Separate the components of the problem.

- Reframe the either/or choice as a both/and challenge.

- Recombine assets, using techniques described in Chapters 6, 7, and 8.

- Learn how to balance commitments by using incubation approaches described in Chapter 5.

- Reconnect with the higher-level purpose provided by the strategic ambition.

The first step is to separate the components of the problem. Here the components were the highly uncertain new market areas, constrained technology resources, go-to-market capabilities, and customers. They each had distinct needs to meet.

Table 12.1 Both/and leadership.

| Either/Or Framing | Both/And Framing | |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunities | We must choose between sustaining the current business and growing. | We can do both by using experimentation to manage exposure to uncertainty. |

| Technology Resources | We are constrained by the availability of specialists. | We can adopt a hybrid team model and train new specialists that will benefit both core and explore. |

| Go to Market Capabilities | Our current sales team must own go to market. | We can segment sales by customer group with the same management to provide integration. |

| Customers | We may lose out if resources are diverted to new areas. | Our current customers benefit from our innovations because they are looking for us to stay competitive. |

This reframing exercise enables different potential solutions, in this case by recombining assets in new ways. For example, a hybrid team approach (see Chapter 8) expanded the responsibility of the software engineering team and brought in additional resources as apprentices to learn how to replicate the secret sauce that made the core business offering so valuable. This created capacity for the new ventures, and it helped sustain efforts to scale the existing business, which is still growing. Another solution was to accept that the answer is incomplete and that you need to learn how best to commit resources. Business experiments are a way of learning and generating data so that we can update our decisions about how to act based on the weight of evidence. This helps to inform the sort of decision you can make: Is it an irrevocable commitment or an incomplete one? At Amazon, they define the difference between one-way doors (once you commit, there is no way back), and two-way doors (you can commit, learn, and decide). This implicitly recognizes that there are at least two different types of problems – ones where the answer is knowable (you have enough evidence to make a choice) and ones which remains complex (without clarity on cause and effect).6

Anna decided to leave the return door open for longer as the business learned. She took an experiment-led approach to exploring the new market opportunities, enabling her to commit incrementally beyond her comfort zone.

Finally, Anna reconnected with her higher-level commitment to the firm's strategic ambition: innovation that improves our customers competitiveness. This connected investments in explore to the needs of the customers Anna was so keen to maintain. Admitting that current customers would likely desert the business if she were not able to sustain her market leadership position gave Anna the motivation to sustain her twin commitments to sustaining growth and developing innovation.

Both/and problem solving is a powerful logical thinking tool that a Corporate Explorer can use to unfreeze a leader's or leadership team's thinking. It allows them to acknowledge their commitment to both exploration and sustaining the current business. However, it does depend on senior leaders that are willing to openly address these issues, to live with the productive tension between the two.

Productive Tension

Capital allocation is one of the most important and contentious aspects of any business. However, these discussions rarely happen in the open. As pressure increases business units defend their turf, even at the expense of the strategic ambition. Every business unit leader wants to maximize their share of resources to help them achieve their growth plans. Although the resources being committed to the new venture may be small in the overall scheme of a corporate R&D investment, its symbolic power is very high. It is activity outside the “normal” system. Hard-pressed business unit leaders striving to meet annual performance targets eye these investments with suspicion. This is true even when they were involved in the decision to fund a Corporate Explorer. At the time they subscribed to the bold strategic ambition and manifesto there were few consequences. It is logical and sounds like the right thing to do. As a Corporate Explorer gets closer to the point of asking for a larger commitment of resources, the decision becomes more consequential. Doubts that business leaders may have suppressed at the beginning, in the name of being a good team member, become more significant when there is a significant financial decision to make. One-time supporters become neutral on whether to back a new venture, and those that were neutral become, overtly or covertly, opponents. The Corporate Explorer needs the senior team to talk about these concerns. If concerns go unaddressed, then the best outcome is a compromise between the competing commitments to stability and exploration. That is a loss for the new venture.

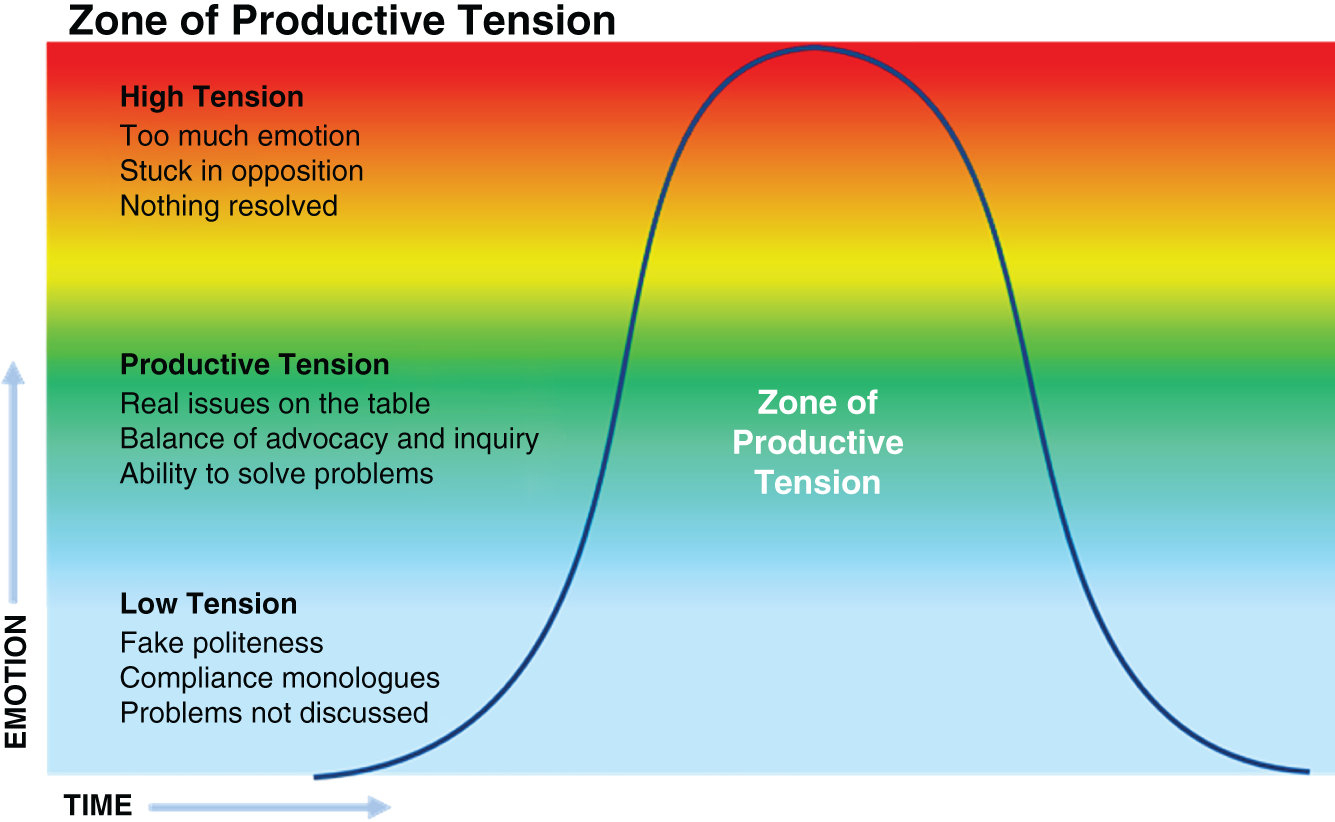

Figure 12.1 Zone of productive tension.

Source: Todd Holzman.

The Corporate Explorer needs to help create productive tension in the group, so that there is a real, open dialogue about whether to invest in scaling the new venture (see Figure 12.1). If tension in a group is too low, then everyone is polite, and no serious issues get discussed. This is a typical response of humans to high-stakes issues that may generate an emotional response. It is the maximize-comfort approach we described earlier. Humans play safe and avoid conflict. It is easy to recognize this from family dynamics. At holidays, we gather with relatives and know to stay clear of certain topics, lest we reignite a long-running dispute. Senior teams are no different. There are unresolved issues that become “undiscussable.” Team members present, there are polite questions, and nothing of substance is discussed. A low-tension conversation where there is no discussion about concerns should be an alarm bell for the Corporate Explorer. That means the issues will get solved outside of any meeting; perhaps the CEO or another power sponsor can succeed, but it becomes more difficult to influence the outcome. The alternative is a high-tension conversation, rich with emotional outbursts and angry exchanges between team members. This is better than ignoring the concerns the team has about investing in the new venture; at least the tension is out in the open. Unfortunately, it is hard to solve a problem when tension is this high. People's logical faculties shut down and they get stuck defending a point of view, rather than trying to understand the other person. Nothing gets resolved in high-tension.

The zone of productive tension is when a conversation has sufficient candor to raise emotion in the group because issues of consequence are being discussed, but not so much that it is impossible for the group to understand one another.

The Mirror

How can Corporate Explorers keep the senior team in the zone of productive tension? They are not usually members of the senior team, so intervening to create a high-stakes conversation is harder, but not impossible. Some CEOs will help by naming the issues that they know concern business-unit leaders and then encourage an open dialogue to resolve them. Even when this happens, it is still useful to have the senior team do the hard work of assessing the situation themselves. Senior teams are full of people with strong opinions, who have been rewarded for acting on them, and have had enough success to believe that they are right most of the time. That means it can be smarter to help them reach a conclusion on their own, rather than advocate it too strongly. One way to do this is to encourage self-diagnosis by holding up a mirror to the situation and asking them what they make of it. If done skillfully, this gets the team to put the issues on the table and leads them into the zone of productive tension where they can solve them.

There are four ways Corporate Explorers can hold up a mirror to the senior team to help them engage in such self-diagnosis of their commitment to innovation. The first is to use a framework to evaluate the key success factors for firms seeking to grow new businesses. This can provoke a self-examination of a firm's readiness to scale new ventures. One Corporate Explorer we worked with used a framework from an article by one of our colleagues and co-authors, Bruce Harreld. He gave the team Bruce's Harvard Business Review article, “Six Ways to Sink a Growth Initiative,” to read.7 He then started his presentation to them by asking them to rate themselves against Bruce's advice (plus two additional criteria) on a scale from 0 to 10, poor to excellent. The self-assessment inspired a rich dialogue about the key gaps in their support to the new venture. The team admitted that it had not done enough to make the resources of the core business available to help scale the venture, nor had they fully engaged with the feedforward metrics used to assess its progress. The Corporate Explorer left with specific commitments on both issues, which led to significant action.

The second approach is to invite an outsider to appraise the status of the new venture and then engage the senior team in dialogue about the progress. We are frequently asked to perform this role with companies. Our impartiality and knowledge of success cases elsewhere helps to provoke an honest conversation in the leadership team. We also sometimes use business school cases that help leaders reason by analogy and learn about their own situations. Any good consultant or facilitator with knowledge of innovation and growth strategies can perform a similar function. If they have sufficient gravitas, they can help to change the course of a senior team conversation.

The third approach is to use the investment decision-making group we described in Chapter 8 as a forum for these tough discussions. If you have designed them as a separate space unlike the normal corporate environment, then this also can encourage open dialogues. Meeting in a more informal environment can inspire deeper conversations that give people more time to listen to one another and open them to information that they might otherwise be unwilling to hear.

The fourth approach is for the Corporate Explorer to role model the radical transparency that they want to encourage the senior team to adopt. That means being tremendously disciplined about how you speak and present data. Instead of being a traditional, corporate manager that advocates for their point of view, and tries to win arguments, you are transparent about what you have learned, what hypotheses are confirmed, which are refuted, and the principal risks that remain to be addressed. If you engage people in dialogue in this way then, over time, it sets a tone for all your interactions. It is not easy to do in the intensity of a corporate environment, where the pressure to “know the answer” is very strong. It is one of the leadership capabilities that a Corporate Explorer can bring to the work of developing an organization's readiness to act. This capability, and the techniques described, are best used throughout the life of the new venture, not just when there is the need for a commitment to invest for scaling. This sets a tone for open dialogue that fosters a constructive dialogue. Even so, dialogue alone will not get you to action. Knowing is not the same thing as doing. There is one additional element that an individual leader brings, courage.

Courage

In 2013, British Telecom's (BT's) then-CEO, Gavin Patterson, made a $2 billion commitment. He decided to bid for the television rights to broadcast UK Premiership Football. This was an audacious move that upped the competition with satellite television provider, Sky TV. Sky had disrupted broadcast television in the UK in the 1990s. It used its deep pockets to attract subscribers to premium sports channels, knowing that for some it was “must-have” TV and they were willing to pay for it. Now, Sky TV had diversified into telephone and broadband. Patterson's competitor was attacking his core business, and he needed a response. He eyed the Premiership Football rights as an audacious counterpunch that would catapult BT into becoming a broadcaster.

Patterson's challenge was that if he won the rights to broadcast Premiership Football, his team would only have one year to set up a live sport broadcasting channel. British Telecom had carefully planned a move into television over many years. Before he was promoted to CEO, Patterson had led the creation of BT Vision in 2007. This provided broadcast TV channels via a set top box connected to BT's broadband internet connection. It was a first in the UK at the time. They had incubated BT TV as a separate, ambidextrous unit, and it put the company in the entertainment industry. It gave them an opportunity to learn about television viewers and subscribers. However, they were distributing content from broadcasters like the BBC, and becoming an actual broadcaster was another level of commitment.8 Although Patterson understood the market and how sports drove television viewership, there was still an act of courage needed to make the step. “When I made the decision, I didn't know what was involved really. I believed in the opportunity and the team that I had. I learned it was harder and more complex than I thought. I'm not sure I would have made the same decision if I had known.”9 Patterson's willingness to commit enabled his nascent business to make the leap to the big leagues. BT is now head-to-head with Sky TV competing for television eyeballs as well as voice minutes and broadband subscribers.

It would be disappointing if after 11 chapters we end the book saying that the fate of a Corporate Explorer comes down to a single act of individual leadership from a courageous CEO like Gavin Patterson. It does not. We have advocated that our Corporate Explorers focus on leading change inside the corporation by building social networks to support them, executing a rigorous, evidence-led approach to innovation that ideates, incubates, and scales new ventures, and then that there are the organizational arrangements that give them appropriate autonomy to act with access to the core business assets. These methods and disciplines are all essential to making you ready to commit. It is critical to frame this commitment as a both/and, to sustain productive tension around that decision with radical transparency, and to learn how you are doing by holding up the mirror.

However, at some point, someone needs to commit. Like Patterson, they need to step off the precipice and enable the new business to scale, even when uncertainty remains. Information reduces uncertainty, it does not eliminate it. You can increase the probability of success but expanding into an emerging market that will always carry more short-term risk than an existing one. Corporate Explorers depend on someone with the courage to commit. Jim Peck had LexisNexis CEO Andy Prozes. Balaji Bondili at Deloitte relied on Matt David. Krisztian Kurtisz at UNIQA had Andreas Brandstetter and Wolfgang Kindl. Innovators at NEC have Takayuki Morita. All these leaders knew when it was time to enter the one-way door. Courage alone though is not enough. Havas, GE, Mozilla, and many others, had leaders who had the courage to commit. They moved too early, however, without applying the three disciplines of innovation and giving the new venture autonomy from the core business and access to its assets. Courage is a necessary but not sufficient condition of success.

Passion

We have given you a detailed blueprint for how to go about building new ventures inside an existing company. We are very confident that aspiring Corporate Explorers can replicate this approach and, if empowered by the right structures, resources, incentives, and scale of ambition, they can succeed. The extra ingredient is courage of the leader to commit and follow through on the opportunity. The Corporate Explorer can inspire this courage with passion. Passion for the possibilities that the new venture will create for the business, in terms of revenue, but also as an incubator for the company's future development. The ventures that our Corporate Explorers lead – Kurtisz at UNIQA, Balaji at Deloitte, Peck at LexisNexis – should not be evaluated with a simple ROI calculation. They each create future options from the capabilities that they develop for the business. A Corporate Explorer should remain objective, open, led by evidence, and yet can still have passion for the possibilities.

Keeping these at the forefront of the minds of the CEO and senior team, as well as the organization, and even shareholders, helps to tilt the balance in favor of exploration. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus taught us that “you cannot put your foot in the same river twice” – when you return the water has already flowed on. The courageous leader is one that steps into the unknown, not because they are certain of what financial return they will get, but because by acting they learn and help to shape where the water will flow next.

We began by promising to demonstrate how corporations have learned to use their assets to create an innovation advantage over startups. We have demonstrated how corporations have set bold, emotionally compelling strategic ambitions to lead disruption in their markets and succeeded. They have done this by applying disciplines that have moved innovation out of the category of “artform” to something that, although lacking scientific rigor, is driven by evidence and understanding, not simply gut instinct. Our Corporate Explorers – Krisztian Kurtisz, Sara Carvalho, Carol Kovac, Jim Peck, Balaji Bondili, Kevin Carlin, and many others – have proven that an explore business system is a possibility, one that is fit for managing in high uncertainty. They have also overcome the silent killers of the core organization, demonstrating skill as leaders of change, not only of innovation.

Becoming a Corporate Explorer is not a route to a safe or easy corporate career. Those that accept the role have chosen to stand out from the crowd, break the rules, and defy the usual corporate career ladder. However, in an uncertain world in which corporation career paths are less structured, the certainties of advancement have become less secure. The capabilities of the Corporate Explorer to manage uncertainty and mobilize an organization around them may be increasingly in demand. Paradoxically, stepping into Heraclitus's River may be the best way to secure a future for company and Corporate Explorer alike.

Chapter Summary

This chapter discussed the final ingredient to success in building new corporate ventures – the readiness of leaders to act. All the factors we have described so far – Corporate Explorer, three disciplines of innovation, ambidextrous organization – will put you in a position to succeed. The final hurdle is committing financially, strategically, and organizationally to scaling the venture.

A CEO has competing commitments. They need to sustain short-term financial results and grow new businesses. When framed as an either/or choice – core or explore – it highlights all the risks associated with supporting the innovation. This can cause CEOs to falter in their commitment to the future.

Corporate Explorers need to influence CEOs and help create a readiness to act. They do this by reframing competition between the core and explore as both/and leadership choices, not either/or choices. Reexamining the logic behind choices helps to find new options that had not been considered.

It also requires a senior team that can engage with productive tension, so that they have authentic conversations that openly discuss the reasons behind opposition to continuing to invest in the new venture. Sometimes, the senior team each has a vested interest in diverting investment back to the core business. Corporate Explorers need to be skilled at helping to hold up the mirror to the senior team at points of high tension. This enables them to do a self appraisal of their motivations.

Finally, these decisions require a leader making a choice to commit. They need courage to leap into the unknown and make something remarkable happen.

Notes

- 1. Michael Tushman, Colin Maclay, and Kerry Herman, “Denver Public Schools 2015: Innovation and Performance?” Harvard Business School Case PEL-076, 2016.

- 2. Meg Wingerter, “Imaginarium Never Got a Chance to Make Change for DPS Students, Some Former Leaders Say,” Denver Post, August 12, 2019, https://www.denverpost.com/2019/08/12/imaginarium-denver-public-schools-achievement-gap/

- 3. Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, “The Real Reason People Won't Change,” Harvard Business Review, November 2001.

- 4. Wendy K. Smith, Marianne W. Lewis, and Michael L. Tushman, “‘Both/And’ Leadership,” Harvard Business Review, June 2016.

- 5. This is a real situation and company; name is disguised to respect confidentiality.

- 6. David Snowden and Mary Boone, “A Leader's Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review, November 2007.

- 7. Donald L. Laurie and J. Bruce Harreld, “Six Ways to Sink a Growth Initiative,” Harvard Business Review, July 2013.

- 8. Michael L. Tushman, David Kiron, and Adam Kleinbaum, “BT Plc: The Broadband Revolution (A),” Harvard Business School, Case 407-001, September 2006 (revised October 2007).

- 9. Interview with author, September 2017.