CHAPTER 2

The GlobalEconomy

________________

Global Economic Evolution

If we go back only 20 years or so to the turn of the century, the total value of goods and services produced around the world (gross domestic product, GDP) stood at the equivalent of US$33 trillion. The world economy has tripled since then and is expected to exceed US$100 trillion in 2022.1 That is an enormous increase, and it is even more impressive when you consider the fact that we suffered three global recessions during that time: the tech bubble, a global financial crisis, and a global pandemic. Admittedly, a majority of the growth in GDP has resulted from the seemingly endless liquidity provided by central banks around the world that has served to drive interest rates lower and help sustain economic growth. In fact, of the $67 trillion increase in world GDP since 1999, an estimated $44 trillion resulted simply from rising prices (inflation), whereas the remaining $23 trillion could be considered “real” economic growth coming from actual increases in production.2 The infinitely complex workings of a world economy driven by the interactions of nearly 7.8 billion people creates a massive pool of investment opportunities, not to mention an equal number of potential hazards for an investor's portfolio. This chapter gives the reader an overview of the global economy, where it is going, and what the implications are for investors. As we look to the future and try to gauge where the global economy is headed, it is best to begin by looking at how we got to where we are today.

The history of the global economy has been marked by periods of extraordinary transformation and expansion. From time to time, the economies of different countries and regions around the world have benefited from human innovations that served to increase productivity and generate significant economic growth. The wealth and improvement in our quality of life that can be created in these periods is remarkable. While some of these transformations have been localized, others have encompassed much of the globe.

An early example of an economic transformation is the Agricultural Revolution, which began in Great Britain in the eighteenth century. The Agricultural Revolution resulted in increased crop yields through the introduction of better crop rotation methods, the use of nitrogen as fertilizer, and advancements in soil drainage. Greater food production meant that more people could be fed, leading to a dramatic increase in the population.3 Another achievement during this time included improvements to infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and inland waterways, which allowed for the more efficient transport of goods.

The Industrial Revolution, which occurred in the late 1700s to mid-1800s, involved the transition from making goods by hand to mass production using newly invented machinery and manufacturing processes. The Industrial Revolution was characterized by a wide range of smaller advancements that, taken collectively, resulted in what many consider to be the most significant economic transformation in history. Among these, the large-scale manufacturing of chemicals and textiles is notable, as was the switch from wood to coal as a source of heat, which allowed for rapid growth in iron production. Transportation networks also improved tremendously during the Industrial Revolution, with the introduction of the railway as well as further improvements to roads and inland waterways. The impact of this remarkable economic transformation was widespread and played a significant role in creating the world economy as we know it today. Over time, these advances led to improvements in our health, education, and overall quality of life, which helped accelerate gains in human productivity. In the words of Ray Dalio, “[h]uman productivity is the most important force in causing the world's total wealth, power and living standards to rise over time.”4

The Digital Economy

Today, we are in what has become known as the technological or Digital Revolution. This transformation began with the invention of computing and the rise of the digital economy. Digitization continues at a rapid pace and is responsible for improvements in healthcare, education, finance, travel, the way we shop, and how we learn about the world around us. Blockchain is one example of a new digital technology that has the potential to transform many different industries. Blockchain is a special type of database that chains together blocks of data to form a sequential record of historical transactions. The data is stored in a way that makes it difficult or impossible to alter, which helps prevent fraud, and it is distributed across many computers, making it difficult for a single person or even group of people to control. While the primary focus of blockchain to date has been to create digital cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, there are many potential applications for the technology that have yet to be explored.

Similarly, some innovations can have dramatic effects on individual industries. In these situations, the impact could be felt globally or limited to a single country or region. For example, innovations or regulatory changes can significantly change the profitability of a specific industry or make a country's entire economy more competitive on the world stage. Conversely, these changes can also make an economy less competitive or less attractive for foreign investment. The global investor must stay alert for new developments that can change business dynamics and create new financial opportunities or risks. The most conscientious investors will take note of these early on, understand their implications, and invest accordingly.

Not all periods of economic transformation are the result of technological innovation. Political upheaval or changes to government policy can also have dramatic effects on the rate of a country's economic growth. A remarkable and more recent economic phenomenon that resulted partly from policy changes is the rise of China. Renowned political scientist Graham Allison explains that “[m]illennia of Chinese dominance ended abruptly in the first half of the nineteenth century when the Qing Dynasty came face-to-face with the power of an industrializing, imperial Western Europe. The following decades were marked by military defeat, foreign-influenced civil war, economic colonization and occupation by outside powers—first by the European imperialists and later by Japan.”5 At the end of this period China's economy was in tatters, with the vast majority of its population living on less than $2 per day.6 In 2010, Robert Zoellick, then president of the World Bank, noted that “[b]etween 1981 and 2004, through a variety of measures, China succeeded in lifting more than half a billion people out of extreme poverty. This is certainly the greatest leap to overcome poverty in history.”7 Assuming China continues to improve the productivity of its workforce, the math is simple. According to Allison, “[i]f over the next decade or two [Chinese workers] become just half as productive as Americans, China's economy will be twice the size of the US economy. If they equal American productivity, China will have an economy four times that of the US.”8

China's economic transition benefited greatly from existing technological know-how in other parts of the world. However, as China's economy has advanced, it has been able to increasingly contribute to the world economy with technological breakthroughs of its own. In fact, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a specialized agency of the United Nations, China was the worldwide leader in patent applications in 2019 after receiving around 1.4 million applications. The United States was second with nearly 600,000 patent applications, while Japan was third with almost 308,000 applications. WIPO estimates that Asia received 65% of all patent applications filed in 2019 worldwide.9 While the United States, Japan, and Europe will undoubtedly continue to be leaders in technological innovation, countries in other regions of the globe are also making significant advancements in terms of technology and productivity.

It is important to remember that economic revolutions or transformations are not merely a thing of the past. We can only guess when the next major technological advancement will occur, but it will probably be met with some initial skepticism and take time to develop. Astute investors recognize the importance of critical innovations at an early stage. Since economic transformations usually take place over extended periods of time, it is often only with hindsight that we can see how significant the events of the day truly were and the extent to which they proved to be a generational opportunity to create wealth for investors. Obviously, not every innovation that comes along is going to change the world. Distinguishing between game-changing innovations and fads is one of the many difficulties the global investor must contend with. A healthy dose of skepticism is required and is an attribute of the most successful investors.

Economic Growth Rates

Most investors regard the world economy as being divided between developed and developing (or emerging) economies. A developing economy is often viewed as one that is dominated by agricultural production but increasingly moving toward modern industrial production. However, the line between developed and developing economies has become blurred, as many countries still referred to as “developing” have made significant advancements and no longer have “backward,” agrarian-based economies. The labels “emerging” and “developing” also imply a high degree of risk that may not accurately reflect the realities of investing in a particular country. Rather than concern myself with labels that may be misleading, I prefer to focus on the size and growth rate of a country's economy, the level of political stability, and the degree to which its capital markets have been developed.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 27 countries around the world generated GDP greater than US$500 billion in 2019. By the year 2026, it is expected that number will grow to 38. In addition, the combined GDP of the top 50 economies is expected to grow from US$87 trillion in 2019 to more than $122 trillion in 2026. This is a cumulative increase of $35 trillion or 40%. Approximately 3% of the annual increase is expected to come from inflation while the remaining 1.9% would represent a real increase in annual global production. In dollar terms, the largest incremental gains in GDP in the period 2019 to 2026 are expected to be led by China, with an increase of nearly US$9.8 trillion, followed by the United States, with an increase of around US$6.2 trillion. This is followed by Japan, Germany, India, and the United Kingdom, which are each expected to grow their economies by more than US$1 trillion by the year 2026.10

Economic growth is subject to unforeseen events that can have a dramatic effect on the world economy. As a result, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to forecast economic growth with any accuracy. The 2020 global pandemic is a prime example of an event that few forecasters predicted, at least in terms of its timing as well as the impact it would have on the world economy and global financial markets. Some might call it futile, but despite our limited ability to accurately predict future events and economic growth rates, economic forecasts remain useful when we try to determine where we are in the economic cycle and where to focus our efforts when we search for businesses in which to invest.

The creation of economic wealth is the engine that will drive future investment returns. To begin our analysis of global economic trends and wealth creation, we can assess with a high degree of certainty the current state of the world and regional economies. Figure 2.1 shows the 10 largest economies in the world as measured by GDP in US dollars. Not surprisingly, the United States and China stand out as the world's economic powerhouses, with Japan, Germany, and India running a distant third, fourth, and fifth, respectively.

While this serves as a starting point, looking at current levels of GDP is essentially looking in the rearview mirror and shows what has already happened. Instead of concerning ourselves with what occurred in the past, our goal is to capture future incremental economic growth and, in the words of Wayne Gretzky, to “… skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” To do this we must also consider the rate at which different regions, countries, and industries are expected to grow in the future. Naturally, actual economic growth rates are likely to deviate meaningfully from expectations. There are many variables that affect economic growth, such as central bank monetary (interest rate) policy, demographic trends, advances in productivity, exchange rate fluctuations, and government fiscal (spending) policy. While basing one's investment decisions solely on these macroeconomic expectations is inadvisable, we can view economic growth rates as tendencies and therefore get an idea of where economic profits are most likely to be generated in the future. With this knowledge in hand, the global investor can increase their odds for success and find industries and geographic regions where economic profits, and therefore wealth, are most likely to increase.

FIGURE 2.1 The World's Largest Economies (2019 GDP in Billions USD)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April, accessed July 17, 2021.

Unfortunately, many of the fastest-growing economies are not easily accessed by foreign investors. Many of the fastest-growing economies have underdeveloped capital markets or restrictions on foreign investment and therefore investment opportunities may be limited or even nonexistent. Still others may not be safe to invest in when you consider the protections afforded to investors. Simply put, some countries may not provide adequate protection of shareholder rights, potentially exposing investors to unnecessary risks, including corruption, poor accounting practices, political instability, or even the nationalization of businesses or entire industries. We discuss these risks in greater detail in Chapter 7, but in the interest of both protecting our capital from unnecessary risks and best allocating our most precious resource, time, we will focus exclusively on investing in markets that have developed capital markets and a regulatory environment that protects shareholder rights for all investors regardless of where they reside.

While economic growth is an important driver of wealth creation, it is only one of many factors we need to consider as investors. With high rates of economic growth could come elevated levels of inflation, which erode the value of money and may turn otherwise attractive investments sour. Other considerations include the level of political and economic stability in which these businesses operate. The price we pay for a business is also critical to determining whether an investment is profitable. You may invest in the highest-quality, fastest-growing business on the planet, but if you pay too much for it you can still lose money on your investment. Balancing what you pay with what you get is challenging and a shrewd investor will walk away from most potential investments. Owning businesses that operate in growing industries and economic regions is preferable to owning those that are in stagnant or declining industries or regions. Simply put, when investing I prefer to “swim downstream with the current” rather than upstream where there may be greater business risks lurking below the surface.

Wealth Creation

When making our decisions on where to invest capital, we should consider expected long-term economic growth. Over time, faster economic growth leads to greater wealth creation, which should result in a more developed equity market. As the value of the equity market increases in size, its importance to the local economy also increases and greater efforts are made to help protect shareholders and thereby enhance the integrity of the market. When we look at stock market capitalization as a percentage of GDP, wealthier countries tend to have more developed financial markets and greater total stock market capitalizations as a percentage of GDP. We discuss these issues in more detail in Chapter 4.

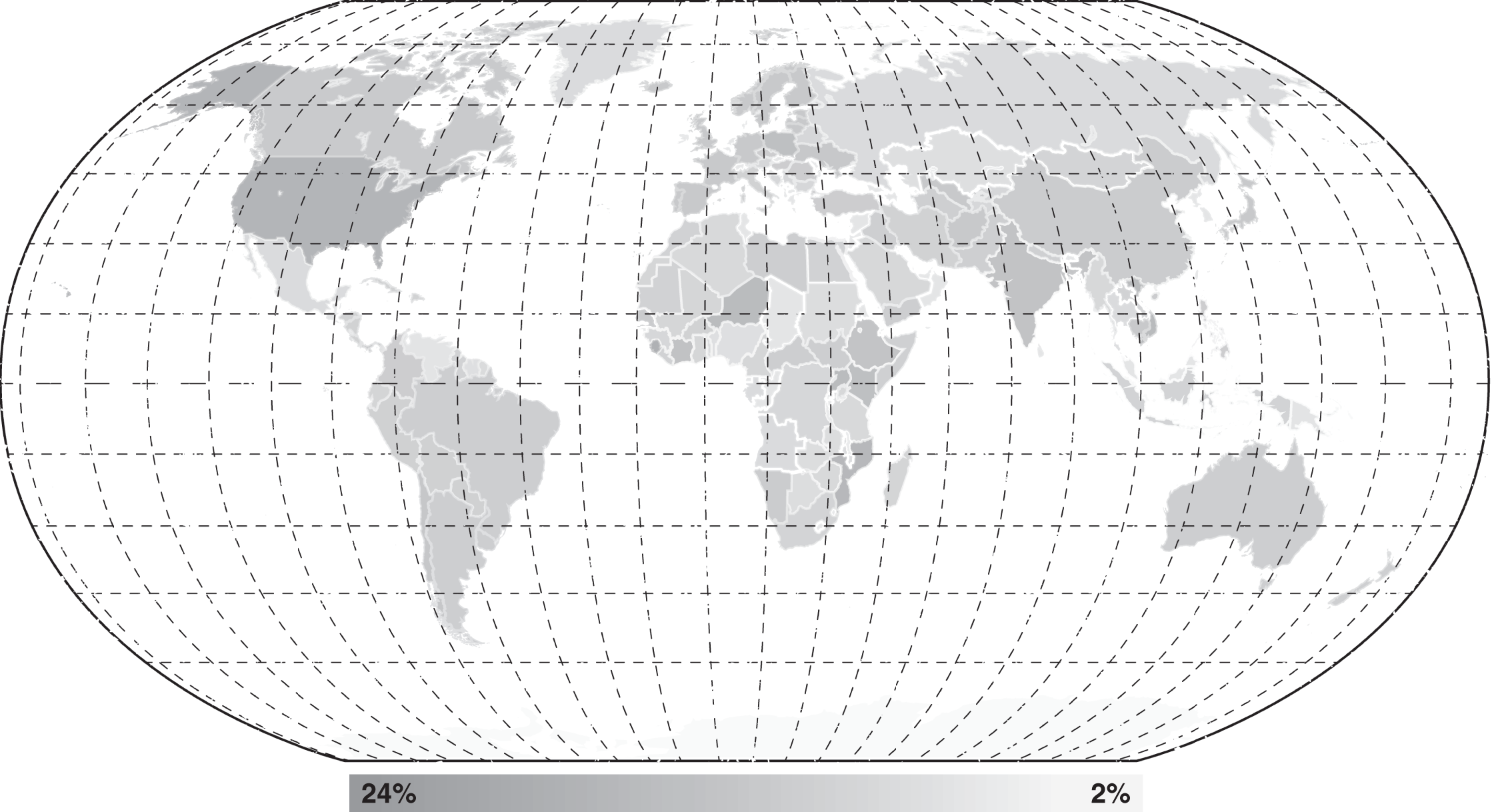

From a regional perspective, there is a large gap between expected economic growth rates. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) currently estimates that developed economies will grow their GDP by an average of 13% from 2022 through 2027, while emerging and developing economies are expected to grow GDP by more than twice that amount at 29%.11 Viewing economic growth forecasts across the globe shows that the highest growth rates are expected in developing Asia and Europe, Africa, and Latin America, as shown in Figure 2.2.

To some degree, the higher economic growth rates in developing countries can be attributed to more favorable demographics. For example, a younger population combined with higher birth rates forms a strong backdrop for economic growth in Southeast Asia. To compensate for lower birth rates and an aging population, the world's developed countries must either expand immigration, incentivize their citizens to have more children, increase exports, or improve productivity. If they do not do any of these things, they will eventually struggle to grow their economies.

As a result of their higher growth rates, emerging and developing economies are slowly but surely becoming a bigger piece of the world GDP pie, and now represent a majority. Figure 2.3 shows how developing countries have grown from 40% of world GDP only 40 years ago to around 60% today, and this trend is expected to continue for the near future.

Combining the current size of the world's economies and adjusting them by their expected growth rates offers investors a glimpse of the future global economic landscape. In other words, if we take the world's economies as they are today and apply a reasonable growth rate to each region, we can get an idea of what the global economy might look like in the future. Of course, this process is highly subjective, and forecasts are prone to being wrong. It is difficult to accurately predict how fast an economy will grow next year, let alone over the next decade. Despite this fact, trying to figure out where and how wealth will be created in the future remains a valuable exercise when thinking about where to invest your capital. As noted earlier, the main reason we want to track economic growth is because it is a primary driver of wealth creation. Greater wealth in turn drives increased demand for goods and services and it forms a growing monetary base that can be invested in real assets (such as real estate), as well as financial assets (like stocks and bonds). By focusing on wealth creation, we are trying to follow the money. Therefore, we can begin by looking at investable assets by region and try to estimate to what level they are likely to grow in the future.

FIGURE 2.2 Total GDP Growth

Source: International Monetary Fund, IMF DataMapper, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD, accessed July 23, 2021. Based on purchasing power parity (PPP) in constant 2017 US dollars.

FIGURE 2.3 Emerging and Developing Economies Share of World GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April, accessed July 22, 2021. Based on PPP in constant US dollars.

Boston Consulting Group (BCG) estimates that the worldwide total of investable assets (such as stocks and bonds) grew 8.3% to a record-high US$250 trillion in 2020, and that investable wealth will grow to US$315 trillion by 2025. They expect the US$65 trillion increase through 2025 to come primarily from North America ($25 trillion), Asia ($22 trillion), and Western Europe ($10 trillion). Real assets (such as precious metals, land, and real estate), which tend to be more prominent in developing economies where financial markets are not as well established or where the local currency may be more volatile, add another $235 trillion to global wealth. BCG also notes that high-growth economies are expected to see a shift from real assets to financial assets.

Over the next five years, however, a combination of greater financial inclusion and growing capital market sophistication will change the wealth composition in growth markets. In Asia, for example, financial asset growth is likely to exceed real asset growth (7.9% versus 6.7%). In particular, investment funds will become the fastest-growing financial asset class, with a projected CAGR [compounded annual growth rate] of 11.6% through 2025. This spike comes as more individuals embrace viable alternatives to investments in traditional real assets.12

Although the highest economic growth rates are expected to occur in developing economies, it is important to keep in mind that the vast amount of wealth already accumulated in developed economies means that a substantial percentage of new wealth creation will continue to come from more advanced economies. Furthermore, even economies with slower growth rates can experience short bursts of growth that can exceed the levels of growth experienced in high-growth economies. Demographic and other structural issues generally prevent these situations from being sustained in the long run, however, and will eventually cause a mature economy to revert lower to its long-term average growth rate.

Effects of Wealth Creation

As the world's economies grow, a part of the wealth that is created will be invested in the local equity market, helping to drive better long-term stock market returns. High-growth economies should have the joint benefit of higher levels of investable wealth as well as an increasingly well-developed stock market in which to invest. Wealth creation is self-perpetuating, as businesses and individuals look for ways to deploy the wealth they have accumulated. Over time, greater spending and new business formations will lead to greater numbers of listed equities and, ultimately, greater capital market sophistication and regulation. Figure 2.4 shows the current amount of financial assets by region.

As a country grows its economy it creates wealth, which in turn can be reinvested in local businesses or spent on goods and services. Subsequently, there are several beneficial side effects of economic growth that create opportunities for global investors.

One such side effect of economic growth is increased healthcare spending. As countries grow their economies, they tend to spend a greater percentage of their GDP on healthcare products, facilities, and services. As of 2019, the average high-income country spent 12.5% of GDP on healthcare, while the average for low-income countries was 4.9%. Figure 2.5 shows how much countries around the world spend on healthcare as a percentage of their GDP. Near the higher end of the range is the United States, which spent around 16.8% of its GDP on healthcare in 2019. The worldwide average for healthcare spending is close to 9.8% of GDP, whereas the average for the least developed countries is only 3.9%.13 As a country's economy grows, not only does the pie become larger, but the size of the healthcare piece becomes larger as a percentage of the total, providing a strong tailwind for the businesses that operate in the healthcare sector. While it currently ranks near the bottom of the list in terms of healthcare expenditures as a percent of its GDP, India is a great example of a country that is benefiting from high levels of foreign and domestic investment in its healthcare industry.

FIGURE 2.4 Financial Assets by Region (Trillions USD)

Source: Boston Consulting Group, “Global Wealth 2021: When Clients Take the Lead,” https://web-assets.bcg.com/d4/47/64895c544486a7411b06ba4099f2/bcg-global-wealth-2021-jun-2021.pdf.

Another side effect of high rates of economic growth is an increase in the number of wealthy individuals. This has created strong demand for luxury goods. Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH) and other luxury goods retailers are seeing extraordinarily strong demand from Asia as newly minted millionaires look for ways to spend their money. Similarly, rapid wealth creation will create strong demand for wealth management services. BCG estimates that wealth management services in Southeast Asia will grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.6% from now until 2025.14 A company like Zurich-based UBS (the world's largest wealth management company) may be particularly well-positioned, given its leading market position in Asia. Interestingly, the 2020 global pandemic served to accelerate the trends toward the accumulation of wealth and increased healthcare spending.

FIGURE 2.5 Healthcare Spending by Country (% of 2019 GDP)

Source: World Bank, World Bank Data Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS&country=, accessed May 1, 2022.

It is often suggested that investors can gain adequate exposure to high-growth economies simply by owning large, developed-economy businesses that sell into those markets. In reality, while there are exceptions, the average company located in an advanced economy generates only a small portion of its revenue from developing economies. A study completed in May 2021 by Morgan Stanley Research showed that North America–based companies generated an average 29% of their revenue from foreign sources, but after excluding the 15% of revenue coming from Japan and Europe only 14% was derived from emerging markets.15 They also found that technology and materials businesses tended to have the highest exposure to emerging markets, at 56% and 48%, respectively. This suggests that North American investors may be able to get adequate exposure to rapid growth in those sectors globally by simply investing “domestically.” However, to gain exposure to other segments of developing economies, investing in a foreign company will likely be necessary. The same study found that while European companies derived close to 30% from emerging markets, the companies that generate the most revenue from developing economies are the businesses headquartered in those markets, where the domestic economy generates an average of 72% of revenues. The implication of this is simple: to obtain the maximum benefit from localized areas of rapid economic growth, investors are often better off investing directly in businesses located in those regions.

Economic growth rates and trends are important considerations for all investors, especially those who see the entire world as their playground. Growth rates in emerging and developing economies are expected to be significantly higher than for developed economies and so maintaining exposure to those regions is likely to pay off for years to come. Keep in mind that these higher growth rates may come with greater risk, a fact that we address later in Part Three, where we discuss the risks of investing globally.

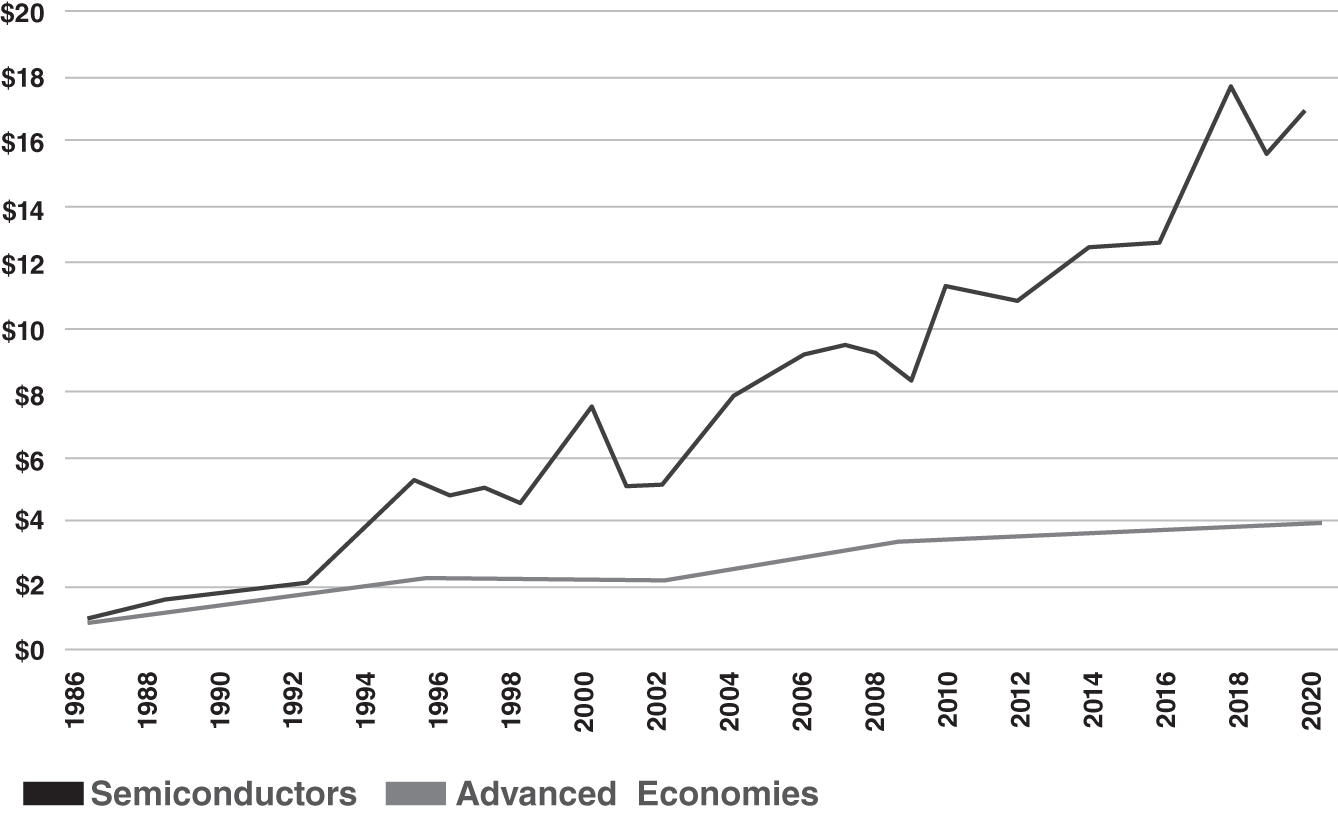

Naturally, great investment opportunities are not limited to high-growth economies. Certain industries within slower-growing, advanced economies can experience prolonged periods of above-average growth. As you can see from Figure 2.6, the semiconductor industry is a terrific example of an industry with an elevated level of sustained growth. Based on worldwide billings, the industry grew at a CAGR of 8.6% globally from 1986 to 2020,16 while advanced economies as a whole grew at only a 4% rate over the same period.17

FIGURE 2.6 Semiconductor Industry Growth versus Advanced Economies

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April, accessed September 9, 2021, and the Semiconductor Industry Association at (https://www.semiconductors.org), accessed September 9, 2021.

Investors should watch the relative growth rates of industries and remain alert for new developments that could cause the growth rate to change. Whether this news will have a positive or negative impact on a company's earnings is not always immediately obvious. Occasionally, stock prices will react to news in the opposite manner from what you would expect. In some cases, there may be mitigating or offsetting factors that affect how investors view new information. Sometimes good news can be construed as bad and at other times bad news can be seen as good. In these situations, good news may be not good enough and prices fall, or bad news may be so bad that investors believe things can only get better and prices rise. This reaction is not easy to predict and can be difficult to decipher by the most experienced investors, even with the benefit of hindsight.

Global Scope Provides Flexibility

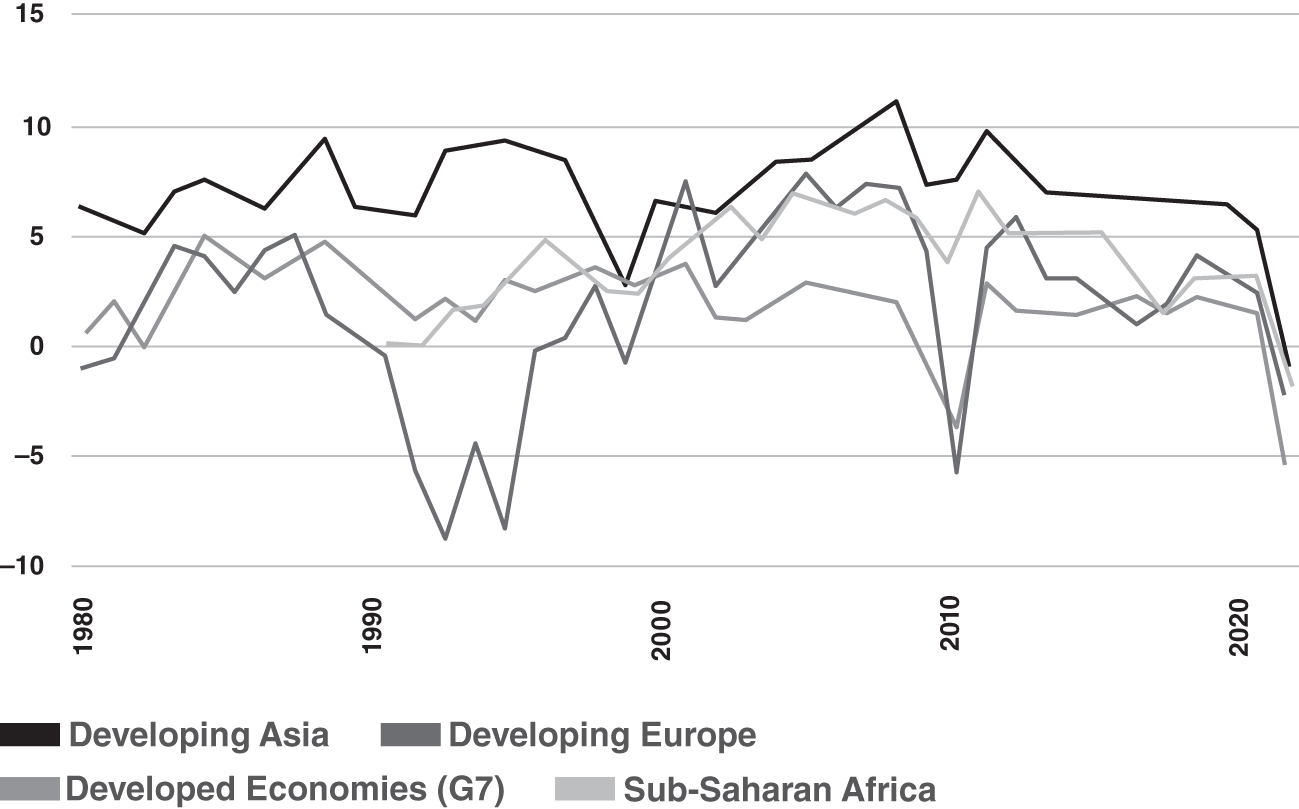

Although the various segments of the world economy tend to move in a synchronous fashion, they do diverge from time to time. Figure 2.7 shows how the economic cycle in select regions can differ meaningfully from one another, especially over shorter periods of time.

FIGURE 2.7 Annual Percentage Change in GDP by Region

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April, accessed September 9, 2021.

As you can see, regional economies do not always move in tandem. During the reintegration of Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, for example, developing Europe showed weak or even contracting economic growth while developing Asia continued to grow. Then in the mid- to late 1990s developing Europe grew strongly while developing Asia was in decline. Whereas the global financial crisis of 2008 had a relatively muted effect on developing economies in Asia and Africa due to their limited exposure to subprime mortgage-backed securities, economies in other regions contracted significantly. Extenuating circumstances may cause one region to lag the world economy for a period only to catch up and accelerate above the worldwide average later. This provides global investors with a potential advantage over investors who limit themselves to their own region or local market. The fact that different regions of the world economy diverge from one another occasionally provides the global investor with greater flexibility, but it also poses a risk, a fact that we discuss in more detail in Chapter 5.

Keep in mind that economic growth does not always translate into corporate earnings growth. Jeremy Siegel noted that “[t]he reason that economic growth does not necessarily increase [corporate earnings] is because economic growth requires increased capital expenditures and this capital does not come freely.”18 That said, earnings growth is more difficult for companies to achieve without underlying economic growth. If your local economy is expected to grow at a below-average rate for an extended period, consider “going global” and diversify into higher-growth economies. At any given point in the economic cycle, differing rates of growth around the world mean that a greater number of investment options are available to those investors who are searching the entire globe for opportunities. No matter what part of the world you live in, taking a global view when assessing sources of growth and wealth creation provides more opportunities to you as an investor.

Notes

- 1. International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Update, July 2021: Fault Lines Widen in the Global Recovery,” https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/07/27/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2021.

- 2. International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Update, July 2021.”

- 3. Mark Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy: 1500–1850 (Cambridge University Press, 1966).

- 4. Ray Dalio, Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail (Simon & Schuster, 2021), p. 28.

- 5. Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? (First Mariner Books, 2018), p. 111.

- 6. Data from World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/.

- 7. World Bank, “World Bank Group President Says China Offers Lessons in Helping the World Overcome Poverty,” September 15, 2010, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2010/09/15/world-bank-group-president-says-china-offers-lessons-helping-world-overcome-poverty (sourced from Allison, p. 15).

- 8. Allison, Destined for War, p. 7.

- 9. The World Intellectual Property Organization, “World Intellectual Property Indicators 2020,” https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4526, accessed July 25, 2021.

- 10. International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Update, July 2021.”

- 11. International Monetary Fund, IMF DataMapper, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD, May 1, 2022.

- 12. Boston Consulting Group, “Global Wealth 2021: When Clients Take the Lead,” https://web-assets.bcg.com/d4/47/64895c544486a7411b06ba4099f2/bcg-global-wealth-2021-jun-2021.pdf.

- 13. World Bank, World Bank Data Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS&country=, accessed May 1, 2022.

- 14. Boston Consulting Group, “Global Wealth 2021.”

- 15. Michelle Weaver, Michael Wilson, Adam Virgadamo, and Andrew Pauker, “Global Exposure Guide 2021—US,” Morgan Stanley Research, 2021. Source: FactSet financial data and analytics.

- 16. Data from World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, Historical Billings Report 35, https://www.wsts.org/67/Historical-Billings-Report.

- 17. International Monetary Fund, IMF DataMapper.

- 18. Jeremy Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns and Long-Term Investment Strategies (McGraw-Hill, 2002), p. 94.