Chapter 12

Implementation: Making It Happen

12.1. Introduction

When I read the summary of the UK Met Office report on climate change (Kendon et al., 2021) I was thinking of borrowing the title from Tom Clancy's novel, Clear and Present Danger. The report has shown that visible evidence of climate change is already here in the UK and that the twenty-first century so far has been warmer than the previous three centuries. The rate of sea level rise has been over 3 mm per year for the period 1993–2019. There can be no doubt looking at these figures that climate change is happening right now.

This is also reflected by the spate of climate-related disasters in July 2021 in geographical areas as widespread as Western Europe, North America, China and South Asia. In August 2021, a UNICEF report (Carrington, 2021) noted that of the 2.2 billion children in the world, almost half were already at “extremely high risk” from the effects of both pollution and climate change, and that nearly every child alive was at risk from at least one risk, such as disease, drought, or air pollution and extreme weather events such as cyclones, flooding and heat wave. The report highlighted the fact that for those living in the 33 countries that constitute the most endangered areas – including sub-Saharan Africa, India and the Philippines – they face the consequences of at least three events at once.

IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2021) also carries the same urgent message of the ‘clear and present danger’ of climate change. This report clearly states, ‘Unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5 °C or even 2 °C will be beyond reach…. Extreme sea level events that previously occurred once in 100 years could happen every year by the end of this century.’ However, it is encouraging to note that the report also suggests that ‘human action has the potential to determine the future course of climate’.

In the preceding chapters I have described plans for both mitigating and adapting to the consequences of climate change. There is a Japanese proverb that says, ‘Action without a plan is a nightmare and a plan without actions is a day dream’. It is clear that we need implementation plans urgently in order to avoid imminent catastrophe – we need to make it happen.

In this chapter implementation plans are presented in two parts:

- Implementation of Climate Change Initiatives

- Implementation of Green Six Sigma

As the primary domain of this book is Green Six Sigma, more details regarding implementation plans are included in the Green Six Sigma sections. This is where this book will add greater values. In the climate change initiatives section, high-level points for implementation are outlined.

12.2. Implementation of Climate Change Initiatives

Any implementation programme including climate change initiatives, whether international or national, should follow a structured plan based on the best practices of project management and change management (Basu, 2009). The implementation plan of Green Six Sigma, as described in Section 9.3, also follows the principle of change management. The success of the implementation of climate change initiatives at a national level, in particular, is linked to the way they are integrated with the economic and social policies of the national government in power. The leadership strategy/attitude to green initiatives of the national government also plays a critical role. There are many learning points that can be derived from earlier implementation projects related to climate change (de Oliviera, 2009; Sharp et al., 2011) that would be useful for other climate change initiatives. These learning points include:

- Start with an immediate and recognisable threat, such as frequent forest fires, hurricanes or flooding. It will help spur action, especially if the community has recently experienced the disaster.

- Begin with a project that can be integrated with an initiative that is already in progress to minimise the duplication of activities and resources.

- Recognise local values and be prepared to be flexible and respond to a community's needs. Reach out to the community and provide open communication.

- Involve elected officials of the local and regional governments early. Although they may not lead on climate change initially, they appreciate being involved and their support is crucial.

- Use outside resources and consultants based on their expertise and track records. Early-stage community organising is the most important skill. Later on, technical experts can help with specific needs to provide the solution.

- Recognise that mitigation can be a first step. Climate mitigation and adaptation are close cousins. If there are separate budgets for mitigation and adaptation for the same problem, combine them.

- Ensure that the project is funded adequately either from a budget or an emergency relief fund.

- Focus critically on data-driven communication, transparency and stakeholder management rather than media-driven public relations.

It is also recommended that the application of Green Six Sigma tools should be considered, and its approaches for ‘fitness for purpose’ and ‘fitness for sustainability’.

A stakeholder is a party that has interest in the project and can influence its outcomes. It cannot be emphasised enough that stakeholder management is crucial to the success of a climate change solution – both to deliver and also to initiate. It is important that key stakeholders are proactive either to activate or influence climate change projects right now.

12.2.1. International Community

The role of the international community is arguably the most crucial driver of implementing any climate change initiatives. 2021 has been coined as a ‘super year’ for the environment. President Joe Biden and other G7 leaders have committed to a new partnership to build back better for the world. The upcoming summits, such as COP26 and the G20, are promising green recovery opportunities from the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite some failures of previous summits, experts are predicting tangible outcomes.

12.2.2. National and Local Governments

There are visible signs that the national, devolved and local governments of the UK have started the implementation of climate change projects. Communities across the UK are tackling the climate crisis with hundreds of local schemes ranging from neighbourhood heating to food co-ops, community land ownership projects and flood defences (The Guardian, 10 March 2021). In spite of the Covid-19 pandemic, major climate change projects have started in other countries as well. Political campaigns by Green parties are also driving changes.

12.2.3. Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs)

There are tens of NGOs, including Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, across the world. These organisations have been campaigning, often by direct action, over decades to influence the policy makers to achieve a greener planet. Now their campaign has changed from policy to actions.

12.2.4. Industry and Service Providers

This is a powerful sector to make changes happen. If the big four corporations of the oil and gas industry get together then alternative aviation fuels will be guaranteed within five years. If the largest private sector consumers of materials like steel, cement and plastics can cooperate then cleaner substitutes will soon be found. The good news is that some of the world's richest people like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are contributing billions of dollars to work to fix the climate crisis. Companies can also invest in their own R&D projects to develop innovative zero carbon products. Many companies around the world have already committed to using renewable energy for a large part of their operations.

12.2.5. The General Public

Every member of the general public is both a consumer and a citizen and, as such, there is much that each of us can do. As a consumer, a person can influence demand for products by fossil fuel energy and as a citizen an adult can vote to change a policy towards achieving climate change solutions. If all of us make individual adjustments in what we buy and use, as discussed in Chapter 10, it will also force the suppliers to change. We can also create demand, say, by buying electric cars and the market will respond accordingly. In a democracy, we can also use our voice to express a view and request change from those in power. As a citizen, if we write to our local elected representative demanding actions for climate change then this can have a real impact.

12.2.6. Media

The media world of newspapers, books, television, radio and social media is playing its role by influencing the mindsets of people and affecting government policies on climate change paradigms. The impact of the movie, ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ by Al Gore in 2006 and the ‘Blue Planet II’ documentary on plastics pollution by David Attenborough in 2017 have been game changers. Progressive newspapers (e.g. The Guardian) and television channels (such as the BBC, who showed ‘Blue Planet’) have been providing fact-based information to inform, educate and update the audience on both climate change challenges and possible solutions. Sky News has dedicated 30 minutes every day to broadcasting news exclusively about climate change. However, there are also some channels and social media platforms feeding ‘fake news’ to the deniers of climate change, and their impact and reach cannot be underestimated.

12.3. The Implementation of Green Six Sigma

The implementation of Green Six Sigma presented here is also part of the application of climate change initiatives. The implementation of Green Six Sigma, and for that matter the instigation of any change programme, is a bit like having a baby – it may be very pleasant to conceive, but the delivery of change can be a tricky process. According to Carnall (1999), ‘the route to such changes lies in the behaviour: put some people in new settings within which they have to behave differently and, if properly trained, supported and rewarded, their behaviour will change. If successful, this will lead to mindset change and ultimately will impact on the culture of the organisation’. The implementation of Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma has been going on for decades. Thus, learning from the proven pathways of both the successful and failed programmes are suggested here for consideration in implementing Green Six Sigma for climate change initiatives.

Below we outline proven pathways for implementing Green Six Sigma for organisations involved in climate change initiatives and potential organisations for climate change that are in different stages of Six Sigma awareness and development. As Green Six Sigma is an adaptation of Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma principles, any reference to Six Sigma or Lean Six Sigma also relates to Green Six Sigma. We have categorised three stages of development:

- New starters of Green Six Sigma.

- Started Six Sigma, but stalled.

- Green Six Sigma for small and medium enterprises.

- Green Six Sigma for successful organisations.

12.4. Implementation for New Starters

There are many large climate change projects waiting to happen where Green Six Sigma can be applied right from the start. The significant projects in this category include the decommissioning of a fossil fuel power plant, building a new regeneration power supply system, a high-speed train project, setting up a new EV manufacturing plant, a major climate change research project (e.g. for carbon capture) and so on.

At the earliest stage the decision makers should understand the urgent need for a climate change initiative towards a net-zero carbon objective and the necessity for an improvement programme underpinned by a data-driven holistic process of Green Six Sigma. The main concern will be the change required to the culture of the organisation and the absence of a proven structure for transformation of a culture. Management knows what they want but how do they convince their staff that they need to or want to change and encourage to buy into the process? And how do they sell Green Six Sigma to stakeholders? You can take a horse to water – but how do you make it drink?

Here I provide a total and proven pathway for implementing a Green Six Sigma programme, from the start of the initiative via the embedding of the change, right through to a sustainable organisation-wide culture. Note that both the entry point and the emphasis on each step of the programme could vary depending on the ‘state of health’ of the organisation.

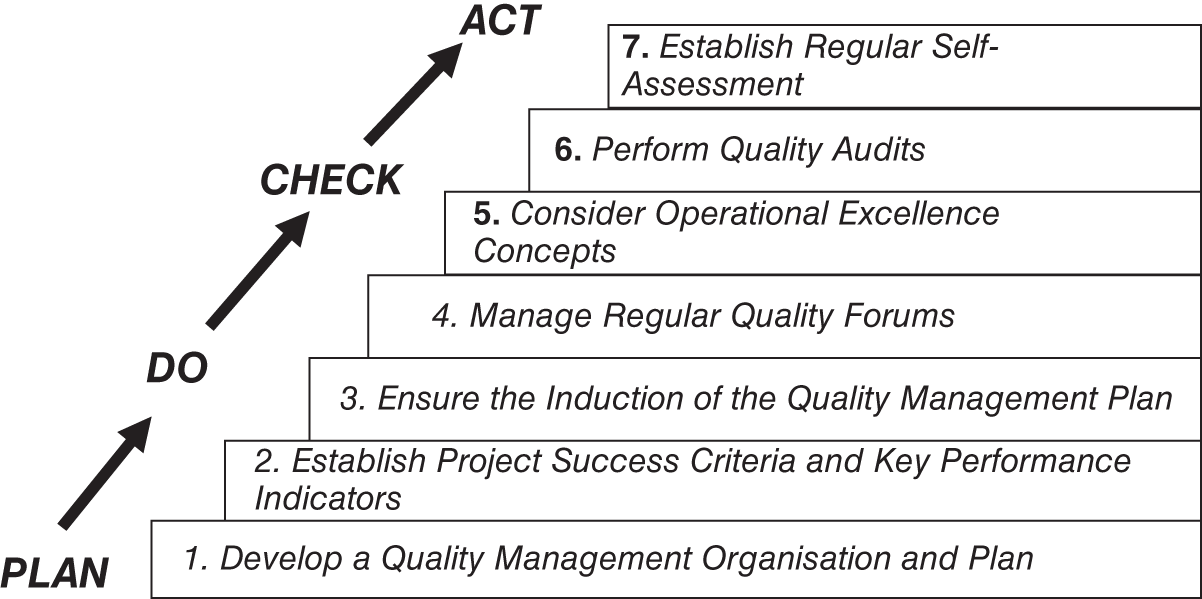

Figure 12.1 Framework of a Green Six Sigma implementation© Ron Basu

The framework of a Green Six Sigma programme is shown in Figure 12.1 and described below.

12.4.1. Step One: Management Awareness

A middle manager has been tasked by the CEO with leading a Green Six Sigma programme in a large organisation that has no previous experience of Six Sigma or Lean Six Sigma. The CEO has just read an article concerning Jack Welch's successes with Six Sigma at General Electric, and he is full of enthusiasm and has high expectations. The middle manager, however, is less enthused; in fact, he does not want to participate at all and has grim forebodings of failure. He realises that the CEO is a powerful member of the board, but after all he is only one member. Meanwhile, in another organisation, the Quality Manager for a medium-sized company has attended a Six Sigma conference and has mixed feelings about the task ahead – optimism as well as some doubts. So, which one of them has the correct approach? In fact, the author believes that both these managers are right to be concerned.

Learnings from previous Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma programmes suggest that it is essential to convince the CEO and at least a third of the board regarding the scope and benefits of Green Six Sigma, prior to launching the programme. The success rate of a ‘back door’ approach without the endorsement of the key players cannot be guaranteed. If a programme is not company-wide and wholly supported by senior management it is simply not Green Six Sigma. It may be a departmental improvement project – but it is not Green Six Sigma. In cricketing terms, a CEO can open the batting, but a successful opening stand needs a partner at the other end.

Research by the Corporate Leadership Council (2005) revealed that through using leadership and change training programmes, companies can substantially increase the potential for change initiatives to be successful. The research also indicated that companies that initiate too much change too quickly actually negatively affect the motivation of employees and their performance.

Learnings from previous Six Sigma programmes suggest that Management Awareness has been a key factor in the successful application of Six Sigma in large organisations. Various methods have been followed including:

- Consultants’ presentation to an offsite board meeting (e.g. General Electric)

- The participation of senior managers in another organisation's leadership workshop (e.g. GSK and Raytheon)

- Study visits by senior managers to an ‘experienced’ organisation (e.g. Noranda's visit to General Electric, DuPont and Alcoa)

Popular Six Sigma literature has advocated that Six Sigma cannot be implemented successfully without top management commitment (Pyzdek, 2003; Ladhar, 2007; Breyfogle, 2008). Moreover, Basu (2009) further argues that if the chief executive does not have a passion for quality and continuous improvement, and if that passion cannot be transmitted down through the organisation, then paradoxically the ongoing driving force will be from the bottom up. It can be argued that the apparent lack of total commitment but tacit support of management has empowered the middle management and acted as an incentive to demonstrate tangible results.

Small- and medium-sized firms can learn from the experience of larger organisations, and indeed there can be mutual benefits for the larger organisation through an exchange of fact-finding missions. A service industry organisation could well benefit by exchanging these sorts of visits with successful Six Sigma companies in the finance sector such as American Express, Lloyds TSB and Egg plc.

During the development of the management awareness phase it is useful to produce a board report or ‘white paper’ summarising the findings and benefits. This account has to be well written and concise, but it should not be rushed. It is recommended that you allow between four and twelve weeks for fact finding, including visits, and the writing of the ‘white paper’.

12.4.2. Step Two: Initial Assessment

Once the agreement in principle from the board is achieved, it is recommended that an initial ‘health check’ should be carried out at the organisation to develop a ‘fitness for purpose’ approach. There are many good reasons for conducting an initial assessment before formalising a Green Six Sigma programme. These include:

- Having a destination in mind and knowing which road to take are not helpful until you find out where you are to start.

- You should get to know the organisation's needs through analysis and measurement of the initial size and shape of the business and its problems/concerns or threats. Once these are ascertained, then the techniques of Green Six Sigma can be tailored to meet these needs.

- The initial assessment acts as a spring board by bringing together a cross-functional team and reinforces the ‘buy in’ at the middle management level.

- It is likely that most organisations will have pockets of excellence along with many areas where improvement is obviously needed. The initial assessment process highlights these at an early stage.

- The health check must take into account the overall vision/mission and strategy of the organisation, so as to link Green Six Sigma to the key strategy of the board. Thus, the health check will serve to reinforce or redefine the key strategy of the organisation.

There are two essential requirements leading to the success of the assessment (health check) process:

- The criteria of assessment (checklist) must be holistic, covering all aspects of the business and specifically addressing the key objectives of the organisation.

- The assessing team must be competent and ‘trained’ in the assessment process. (Whether they are internal or external is not a critical issue.)

It is sensible that the assessment team be trained and conversant with basic fact-finding methods, such as those used by industrial engineers. Some knowledge of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM, 2003) would be most useful.

Once the health check assessment is completed a short report covering strengths and areas for improvement is required. It is emphasised that this report should be short (not the 75 page detailed account required for the EFQM). In writing the document the company might require the assistance of a Six Sigma consultant. The typical time needed for the health check is two to six weeks.

12.4.3. Step Three: Programme Brief and Organisation

This is the organisation phase of the programme requiring a clear project brief, the appointment of a project team and the development of a project plan. All elements are essential since ‘major, panic driven changes can destroy a company; poorly planned change is worse than no change’ (Basu and Wright, 1997).

The brief must clearly state the purpose, scope objectives, benefits, costs and risks associated with the programme. A Green Six Sigma syllabus is a combination of Total Quality Management, Lean Management, Six Sigma and culture change supervision. It is a huge undertaking and requires the disciplined approach of project management. ‘Programme management is a portfolio of projects that change organisations to achieve benefits that are of strategic importance’ (MSP, 2007).

One risk at this stage is that management might query the budget for the programme, and there might be some reluctance to proceed. If this is the case, then it is obvious that management has not fully understood the need for change. This is why the importance of the first step, ‘Management Awareness’, is stressed. However, reinforcement could be needed during step three, underpinned with informed assumptions and data including a cost/benefit/risk analysis. Unless management is fully committed there is little point in proceeding.

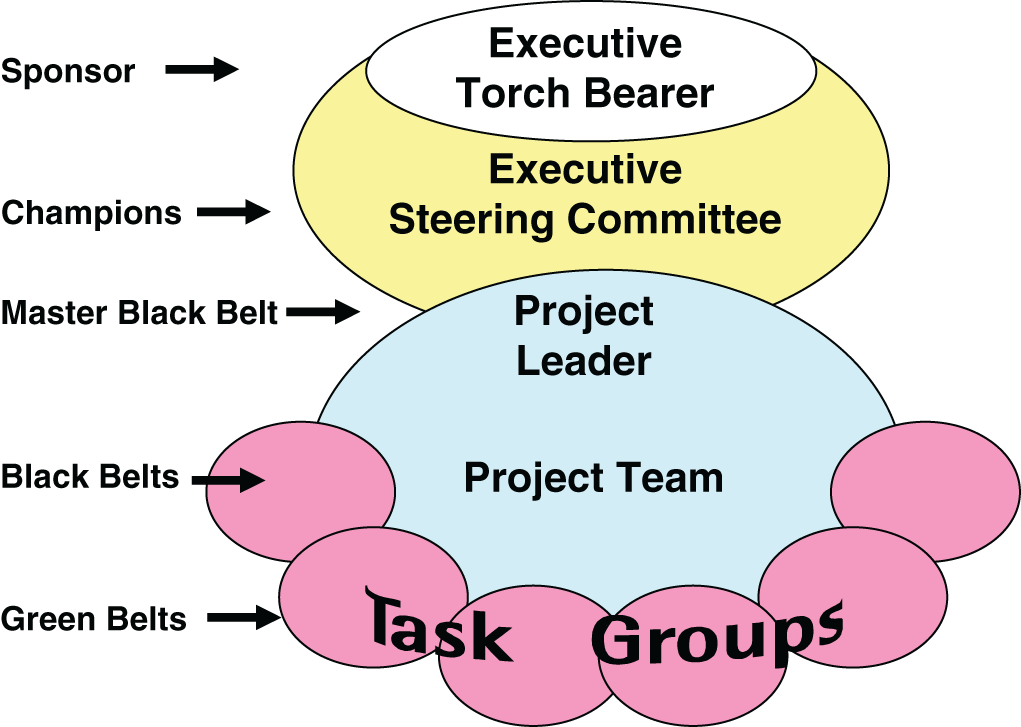

There is no rigid model for the configuration of the Green Six Sigma team. Basic elements of a project structure for a major change programme can be found in Basu and Wright (1997). A tested Green Six Sigma model is shown in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2 Green Six Sigma programme organisation© Ron Basu

Executive Torch Bearer

Figure 12.2 shows an Executive Torch Bearer, who ideally will be the chief executive officer (CEO) and will be the official sponsor for Green Six Sigma. There is a correlation between the higher up the organisation the Torch Bearer is and the greater the success of the programme. The role of the Torch Bearer is to be the top management focal point for the entire programme and to chair the meetings of the Executive Steering Committee. Being a Torch Bearer may not be a time-consuming function, but it is certainly a very important role to give the programme a high focus, to expedite resources and to eliminate bottlenecks.

Executive Steering Committee

To ensure a high level of commitment and ownership to the project, the steering committee should be drawn from members of the board plus senior management. Their role is to provide support and resources, to define the scope of the programme consistent with corporate goals, to set priorities and consider and approve the programme team recommendations. In Six Sigma terminology they are the champions of processes and functional disciplines.

Programme Leader

The Programme Leader should be a person of high stature in the company – a senior manager with broad knowledge of all aspects of the business and possessing good communication skills. He or she is the focal point of the project and also the main communication link between the Executive Steering Committee and the programme team. Often the Programme Leader will report direct to the Torch Bearer.

The Programme Leader's role can be likened to that of a consultant. The function of the Leader is to a great extent similar to Hammer and Champy's ‘czar’ in Re-Engineering the Corporation (1993). In other words, the Programme Leader's task is to:

- Provide necessary awareness and training for the project team, especially regarding multi-functional issues,

- Facilitate the work of various project groups and help them develop and design changes and

- Interface across functional departments.

In addition to the careful selection of the Programme Leader, two other factors are important in forming the team. Firstly, the membership size should be kept within manageable limits. Secondly, the members should bring with them not only analytical skills but also an in-depth knowledge of the total business covering marketing, finance, logistics, technical and human resources. The minimum number of team members should be three, with a maximum of seven. Any more than even this figure can lead to a series of practical difficulties such as arranging meetings, communicating and keeping to deadlines. The dynamics within a group of more than seven people allows a pecking order to develop and for sub-groups to emerge. The team should function as an action group, rather than as a committee that deliberates and makes decisions. Their role is to:

- Provide objective input into the areas of their expertise during the health check stage

- To lead activities when changes are made

For the Programme Leader the stages of the project include:

- Education of all the people in the company

- Gathering the data

- Analysis of the data

- Recommending changes

- Regular reporting to the Executive Steering Committee and to the Torch Bearer

Obviously, the Programme Leaders cannot do all the work themselves. A Programme Leader has to be the type of person who knows how to make things happen and who can motivate and galvanize other people to help achieve this aim.

Programme Team

The members of the Programme Team represent all functions across the organisation and they are the key agents for making changes. Members are carefully selected from both line management and a functional background. They will undergo extensive training to achieve Black Belt standards. Our experience suggests that a good mix of practical managers and enquiring ‘high flyers’ will make a successful project team. They are very often the process owners of the programme. Most of the members of the Programme Team are part time. As a rule of thumb, no less than one percent of the total workforce should form the Programme Team. In smaller organisations the percentage will of necessity be higher so that each function or key process is represented.

Task Groups

Task Groups are spin-off sets formed on an ad hoc basis to prevent the Programme Team getting bogged down in detail. A Task Group is typically created to address a specific issue. The topic could be relatively major, such as the Balanced Score Card, or comparatively minor, such as the investigation of losses in a particular process. By nature, the Task Group members are employed directly on to the programme on a temporary basis. However, by supplying basic information for the programme, they gain experience and Green Belt training. Their individual improved understanding and ‘ownership’ of the solution provide a good foundation for sustaining future changes and ongoing improvements.

Time Frame

A preliminary time plan with dates for milestones is usually included in the Programme Brief.

The ‘Do’ Steps

In Figure 12.1 we can see that after the ‘Plan’ phase there comes the ‘Do’ phase.

Once the programme and project plan have been agreed by the Executive Steering Committee it should receive a formal launch. It is critical that all stakeholders, including managers, employees, unions, key suppliers and important customers are clearly identified. A high-profile programme launch targeted at stakeholders such as these is desirable.

12.4.4. Step Four: Leadership Workshop

All board members and senior managers of the company need to learn about the Green Six Sigma programme before they can be expected to give their full support and input into the scheme. Leadership training is a critical success factor. Leadership Workshops can begin simultaneously with Step One, but should be completed before Step Five (see Figure 12.1). Workshops will last between two and five days and will cover the following issues:

- What are Six Sigma and Green Six Sigma?

- Why do we need Green Six Sigma?

- What will it cost and what resources will be required?

- What will it save, and what other benefits will accrue?

- Will it interrupt the normal business?

- What is the role of the Programme Leader and the Executive Committee?

12.4.5. Step Five: Training Deployment

The training programme, especially for the team members, is rigorous. One might question whether it is really necessary to train in order to achieve Black Belt certification. Indeed, formal certification might not be essential. However, there is no doubt that without the in-depth training of key members of the programme, little value will be added in the short term, and certainly not over a longer period. The training/learning deployment creates a team of experts. It is presupposed that programme members will be experts in their own departments and processes as they are currently being run. It is expected that they will have the capability of appreciating how the business as a whole will be organised in the future. Green Six Sigma will equip them with the tools for the business overall in order to achieve world class performance.

Apart from the rigorous education in techniques and tools, it is emphasised that the training will change how the members will look at things. Training is an enabler, not only to understand the strategy and purpose of change but – as evidenced by the experience of American Express – it will help members to identify:

- Project replication opportunities

- Leveraging the results of the programme

- Identification and elimination of areas of rework

- Drivers for customer satisfaction

- Leverage of Green Six Sigma principles into new products and services

Smaller organisations are very often concerned about the cost of training, especially the money paid out to consultants and for courses. In a Green Six Sigma programme teaching costs can be minimised by the careful selection of specialist consultants and through the development of own in-house training programmes.

12.4.6. Step Six: Project Selection and Delivery

The Project Selection process usually begins during the Training Deployment Step.

Project selection, and subsequent delivery, is the visible aspect of the programme. A popular practice is to begin by having easy, and well publicised, successes (known as ‘harvesting low hanging fruit’). We recommend that ‘quick wins’ should be aimed for (or ‘just do it’ projects).

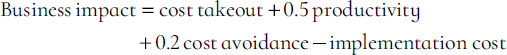

In a similar fashion, Ericsson AB applied a simplified ‘Business Impact’ model for larger schemes. They categorise ventures under three headings:

- Cost Takeout

- Productivity

- Cost Avoidance

Table 12.1 Categories of savings

| Level | Cost Takeout | Productivity and Growth | Cost Avoidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | ‘Hard’ savings - Recurring expense prior to Six Sigma - Direct costs | ‘Soft’ savings Increase in process capacity so you can ‘do more with less’, ‘do the same with less’, ‘do more with the same’ | Avoidance of anticipated cost or investment that is not in today's budget |

| Example |

|

|

|

| Impact | Whole unit | Partial unit | Not in today's cost |

| Weighting | 100% | 50% | 20% |

A variable weighting is allocated to each category, as shown in Table 12.1.

For smaller, ‘just do it’ projects, it is a good practice to establish an ‘Ideas Factory’ to encourage Task Groups and all employees to contribute to savings and improvement. Very often small projects from the ‘Ideas Factory’ require negligible funding.

Project Review and Feedback

One important point of the Project Selection and Delivery Step is to monitor the progress of each task and to control the effects of the changes so that expected benefits are achieved. The Programme Leader should maintain a progress register supported by a Gantt Chart, defining the change, expected benefits, resources, time scale, and expenditure (to budget), and showing the people who are responsible for each of the identified actions.

This phase of review and feedback involves a continuous need to sustain what has been achieved and to identify further opportunities for improvement. It is good practice to set fixed dates for review meetings as follows:

- Milestone Review (at least Quarterly)

- = Executive Steering Committee,

- Torch Bearer, and

- Programme Leader

- = Executive Steering Committee,

- Programme Review (Monthly)

- = Programme Leader and Team,

- with a short report to Torch Bearer

- = Programme Leader and Team,

The problems/hold-ups experienced during projects are identified during the Programme Review with the aim of the project team taking action to resolve sticking points. If necessary, requests are made to the Executive Steering Committee for additional resources.

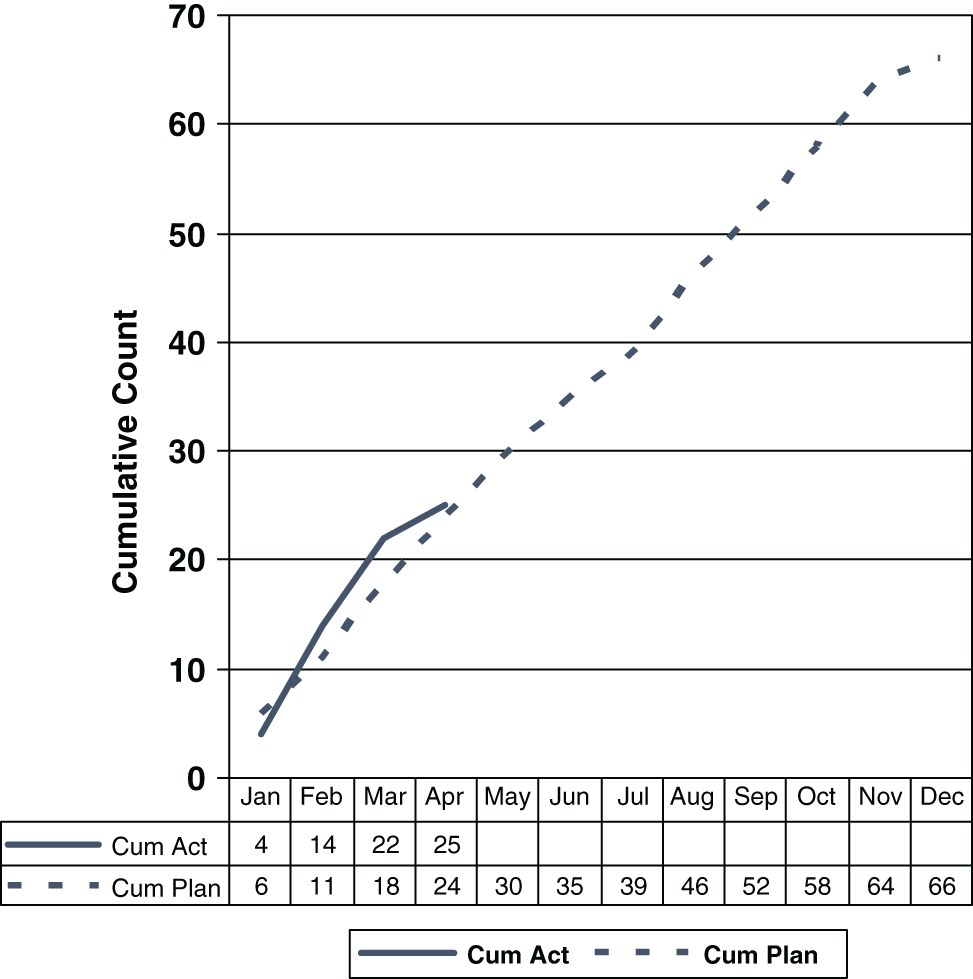

12.4.7. Step Seven: Measurement of Success

The fundamental characteristic of a Six Sigma or Green Six Sigma programme that differentiates it from a traditional quality curriculum is that it is results orientated. Effective measurement is the key to understanding the operation of the process, and this forms the basis of all analysis and improvement work. In a construction project the milestones are both tangible and physically obvious, but in a change programme such as Green Six Sigma the modifications are not always apparent. It is essential to measure, display and celebrate the achievement of milestones in a Green Six Sigma programme, and in order to improve and sustain its results, the importance of performance management is strongly emphasised. The process and culture of measurement must start during the implementation of changes.

The components of measurement of success should include:

- Project tracking

- Green Six Sigma metrics

- Balanced Score Card

- Self-assessment review (e.g. EFQM or Baldridge).

There are useful software tools available such as Minitab (www.minitab.com) for carrying out detailed tracking of larger Six Sigma projects. However, in most programmes the progress of savings generated by each project can be monitored on an Excel spreadsheet. It is recommended that summaries of results are reported and displayed each month. Examples of forms of displays are shown in Figures 12.3 and 12.4.

Figure 12.3 Project planned and completed© Ron Basu

Figure 12.4 Value of planned and completed projects© Ron Basu

Green Six Sigma Metrics

Green Six Sigma metrics are required to analyse the reduction in process variance and the reduction in the rate of defects resulting from the appropriate tools and methodology.

A word of caution: Black Belts can get caught up with the elegance of statistical methods and this preoccupation can lead to the development of a statistical cult. Extensive use of variance analysis is not recommended.

The following Green Six Sigma metrics are useful, easy to understand and easy to apply:

- Cost of Poor Quality = COPQ ratio

- Defects per Million Opportunities = DPMO and

- First Pass Yield = FPY

- Carbon Footprint

COPQ

DPMO

- Total number of defects × 1,000,000

- Total units and opportunities per unit

FPY

- Number of units completed without defects and rework

- Number of units started

Carbon Footprint

A carbon footprint is the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions caused by an individual, event, organisation or process expressed as a carbon dioxide equivalent. There are digital tools available (e.g. Emitwise, emitwise.com) for automatic calculations of carbon footprints.

By measuring and monitoring Green Six Sigma metrics each month, opportunities for further improvement will be identified.

As has already been emphasised in Chapter 5, a carefully designed Balanced Score Card is essential for improving and sustaining business performance. It is generally agreed that the Balanced Score Card is applicable for a stable process and thus should be appropriate after completion of the Green Six Sigma programme. This may be so, but unless the measures of the Balanced Score Card are properly defined and designed for the purpose at an early stage, its effectiveness will be limited. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that during the Green Six Sigma programme the basics of the Balanced Score Card should be established in order to manage the company-wide performance system.

The fourth component of measurement is the ‘self-assessment and review’ process. There are two options to monitor the progress of the business resulting from the Green Six Sigma programme, and either of the following can be used:

- A simple checklist to assess the overall progress of the programme or

- A proven self-assessment process such as the European Foundation of Quality Management (EFQM) or the American Malcolm Baldridge system.

In the initial health check appraisal stage, the use of EFQM is advocated; thus the methodology will already have been applied. Additionally, it gives further experience in the self-assessment process, which will enable future sustainability. Finally, it will provide the foundation should the organisation wish at a later stage to apply for an EFQM or Baldridge award.

12.4.8. Step Eight: Culture Change and Sustainability

A culture change must not begin by replacing middle management by imported ‘Black Belts’. Winning over as opposed to losing middle management is essential to the success of Green Six Sigma, or for that matter any quality initiative.

What is required is that the all-important middle management, and everyone else in the organisation, understands what Green Six Sigma is and possesses the culture of quality.

The Green Six Sigma Culture is shown in Table 12.4.

Green Six Sigma requires a balanced culture comprising the key characteristics of the above four categories. If an organisation is predominantly one type, then some cultural change will be required. Training Deployment, see Step Five of Figure 12.5, includes preparation for culture change, but education alone will not transform the mindset required for Green Six Sigma.

Table 12.4 Green Six Sigma Culture

|

Communication

Finally, the key to sustaining a Green Six Sigma culture is the process of good communication. Methods of communication include:

- A Green Six Sigma website, specifically developed, or clearly visible on the corporate website

- Specially produced videos

- A Green Six Sigma monthly newsletter

- Internal emails, voicemails, memos with updated key messages – not slogans such as ‘work smarter not harder’ and other tired clichés

- Milestone celebrations

- Staff get-togethers, such as special morning teas, a Friday afternoon social hour or ‘town hall’ type meetings

- An ‘ideas factory’ or ‘think tank’ to encourage suggestions and involvement from employees

12.4.9. Step Nine: Improve and Sustain

‘Improve and sustain’ is the cornerstone of a Green Six Sigma programme. This is similar to Tuckman's (1965) fifth stage of team dynamics for project teams (‘Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and Mourning’). During the Mourning step the project team disbands and members move onto other ventures or activities. They typically regret the end of the project and the breakup of the group, and the effectiveness or maintenance of the new method and results gradually diminish. In Chapter 5 we have discussed in some detail that, in order to achieve sustainability, four key processes must be in place:

- Performance management

- Senior management review

- Self-assessment and certification

- Knowledge management

The ‘end game’ scenario should be carefully developed long before the completion of the programme. There may not be a sharp cut-off point like a project handover and the success of the scenario lies in the making of a smooth transition without disruption to the ongoing operation of the business.

As part of the performance management, improvement targets should be gradually, and continuously, stretched and more advanced tools considered for introduction. For example, the DFSS (Design for Six Sigma) is resource hungry (Basu, 2009) and can be considered at a later stage in a Green Six Sigma programme. With Six Sigma, the aim is to satisfy customers with robust ‘zero defect’ manufactured products. In order to do so, DFSS is fully deployed covering all elements of Manufacturing, Design, Marketing, Finance, Human Resources, Suppliers and Key Customers (including the supplier's suppliers and the customer's customers).

At an advanced stage of the programme, a milestone review should be included in senior management operational review team meetings (such as the sales review meetings and operational planning meetings/committees). In other words, a milestone review should occur not only within the Green Six Sigma Executive Steering Committee.

It is recommended that a pure play EFQM (or other form of self-assessment) should be incorporated as a six-month feature of the Green Six Sigma programme. Even if the company gains an accolade, such as an EFQM or Baldridge award, the process must still continue indefinitely.

Two specific features of knowledge management need to be emphasised. Firstly, it is essential that the company seek leverage from Green Six Sigma results by rolling out the process to other business units and main suppliers. Secondly, it is equally important to ensure that career development and reward schemes are firmly in place to retain the highly trained and motivated Black Belts. The success of the sustainability of Green Six Sigma occurs when the culture becomes simply an undisputed case of ‘this is the way we do things’.

Time Scale

The time scale of Green Six Sigma implementation will last several months and is, of course, variable. The duration not only depends upon the nature or size of the organisation but also on the business environment and the resources available. Four factors can favourably affect the time scale:

- Full commitment of top management and the board

- Sound financial position

- Correct culture (workforce receptive to change)

- A competitive niche in the marketplace

It is good practice to prepare a Gantt Chart containing the key stages of the programme and to use it to monitor progress. Figure 12.5 shows a typical timetable for a Green Six Sigma agenda in a single-site medium-sized company. The diagram shows an order of magnitude only, and the sequence could well vary. The time line is not linear, stages overlap and frequent retrospection should occur in order to learn from past events and work towards future progress.

Figure 12.5 A typical time plan for a Green Six Sigma programme

12.5. Green Six Sigma for ‘Stalled’ Six Sigma

Some organisations have already attempted to implement a Six Sigma (or a TQM) programme, but the process has stalled. Results are not being achieved and enthusiasm is waning; in some cases the programme has effectively been abandoned. The reasons for stalling are various but often progression has ground to a halt due to an economic downturn (such as that experienced in the Telecommunications industry in 2001), a change in top management or a merger or takeover.

There are some organisations in this category who applied Lean Six Sigma for a specific project but not across the whole organisation, e.g. Network Rail in Case Example 9.3. These organisations will benefit by focusing on a net-zero carbon strategy supported by an organisation-wide Green Six Sigma approach.

Green Six Sigma: Not a ‘Quick Fix’

During restructuring, or if the company is in survival mode, the implementation of Green Six Sigma is not appropriate. Green Six Sigma is not simply a ‘quick fix’, a plaster hastily stuck over gaping wounds, and in such cases it is not sufficient. Instead, the underlying, more serious, issues must be addressed. After applying the short-term cost saving measures of a survival strategy, when the business has stabilised and a new management team is in place, then Six Sigma can be restarted. However, this time it should be done correctly, and using the Green Six Sigma approach.

It is likely when restarting that many of the steps will not need to be repeated, including Training/Learning Deployment. However, in a restart there is one big issue that makes life more difficult, and that is credibility. How do you convince all the necessary people that it will work the second time around, when things did not come together at the first attempt? This will put special pressure on Step Eight, Culture Change. The employees could well be tired of excessive statistics and complex Six Sigma tools. Thus the selection of appropriate tools is a strong feature of Green Six Sigma.

The Green Six Sigma programme for a re-starter will naturally vary according to the condition of the organisation, but the programme can be adapted within the framework shown in Figure 12.1. The guidelines for each step are:

- Management Awareness. If there is none, then you cannot re-start.

- Initial Assessment. This has to be the re-start point. Where are we, where do we want to go?

- Programme Brief and Organisation. The programme will need to be re-scoped and new teams formed.

- Leadership Workshop. This will be essential, even if management has not changed.

- Training/Learning Deployment. Appropriate tools should be selected. If past team members, in particular Black Belts, are not happy with the terminology of the old programme, then new expressions should be used. The title ‘Black Belt’ in itself is not sacrosanct and might be changed. If the ‘old’ experts are still in the organisation, then training time might be reduced; for example, a workshop of only one week's duration might be sufficient.

- Project Selection and Delivery. This is the same as the full Green Six Sigma programme; harvest the ‘low hanging fruit’.

- Measurement of Success Review. This involves looking at the old measures, ascertaining what worked and what did not, and following the full Green Six Sigma programme.

- Culture Change. This will be critical. Top management support must be extremely evident. Reward and appraisal systems will have to be aligned to Green Six Sigma.

- Improve and Sustain. Same as for Green Six Sigma.

12.6. Green Six Sigma for Small and Medium Enterprises

There are many small and medium enterprises (SMEs) which are delivering products and services for climate change initiatives, especially for retrofitting buildings. These are the companies engaging in the manufacture of heat pumps, home insulation and the circular economy.

The organisation structure of the programme will vary according to the nature and size of the organisation. For small and medium enterprises (SMEs) a typical structure is as shown in Figure 12.6. In small enterprises the Programme Leader might be part time. In all other cases the Programme Leader will be full time.

Small and Medium Enterprises may follow the DMAIC Lite process (Basu, 2011). Similar to the full DMAIC process, the DMAIC Lite procedure has three structured steps (viz. Define, Measure and Analyse and Improve and Control). However, the boundaries between ‘Measure’ and ‘Analyse’ and also between ‘Improve’ and ‘Control’ are more flexible in the DMAIC Lite version. DMAIC Lite should be followed by the sustainability tools of Green Six Sigma.

Figure 12.6 Green Six Sigma structure for SMEs© Ron Basu

12.7. Green Six Sigma for Successful Organisations

There are some organisations that have been consciously engaged in successful Lean Six Sigma projects to achieve clean energy or green transports. The examples in this category include Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System (Case Example 7.1) and Tesla Electric Vehicles (Case Example 9.2). The approach for these projects should be to focus on the sustainability tools of Green Six Sigma. This is also a case for ‘we've completed Six Sigma, but where to now?’

William Stavropoulos, the CEO of Dow Chemical, is reported to have once said, ‘The most difficult thing to do is to change a successful company.’ It is true that employees of firms enjoying a high profit margin with some dominance in the market are likely to be complacent and to feel comfortable with the status quo. Perhaps it is even more difficult to remain at the top or to sustain success if the existing strategy and processes are not adaptable to change. Darwin famously observed, ‘It is not the strongest species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.’ It is possible for the management of some companies, after the completion of a highly successful Six Sigma programme, to find their attention diverted to another major initiative such as e-business or Business to Business Alliances. Certainly, new schemes must be pursued, but at the same time the long-term benefits that could be achieved from Six Sigma should not be lost. Green Six Sigma for sustainability – staying healthy – is the answer.

If a company has succeeded with Six Sigma, then the time is now right to move onto Green Six Sigma to achieve Step Nine: Improve and Sustain.

12.8. External Consultants

Many businesses, especially SMEs, are often concerned with the cost of consultants for a Six Sigma programme. Large consulting firms and academies for Six Sigma could well expect high front-end fees. However, with Green Six Sigma the recommended approach is to be selective in the use of outside consultants. We advocate that you should use outside consultants to train your own experts, and to supplement your own expertise and resources when necessary. No consultant will know your own company as well as your own people. For this reason, the use of external consultants is not favoured in the role of the Programme Leader.

In a Green Six Sigma programme the best use of consultants is in:

- Step Two: Initial Assessment. Here one would use a Six Sigma expert or an EFQM consultant to train and guide your team

- Steps Four and Five: Leadership Workshop, and Training/Learning Deployment. Outside consultants will be needed to facilitate the Leadership Workshops, and to tutor your own ‘Black Belts’. Once trained, your own ‘Black Belts’ will in turn train ‘Green Belts’ and develop new ‘Black Belts’.

- Step Eight: Culture Change. An outside consultant is best suited to develop a change management plan for a change of culture.

12.9. Summary

Chapter 12 provides practical guidelines for selecting appropriate tools and techniques and ‘making it all happen’ in a quality programme like Green Six Sigma. Many a Six Sigma exercise started with high expectations and looked good on paper. Many an organisation has been impressed by success stories of Six Sigma, but unsure of how to start. The implementation plan shown here will enable any organisation at any stage of a Green Six Sigma initiative to follow a proven path to success and to sustain benefits. The implementation plan has nine steps, beginning with Management Awareness right through to the ongoing process of Improve and Sustain. There is no end to the process of striving for and measuring improvement.

In the spirit of Green Six Sigma, fit for purpose, this framework can be adjusted and customised to the specific needs of any organisation. Explicit comments have been included in this chapter for the implementation of Green Six Sigma in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) where resources are constrained (see Sections 12.4.1 and 12.4.3). Instead of all nine steps in Figure 12.1, SMEs should focus primarily on steps 1, 3, 5, 6 and 9.

At all stages of the programme, it is essential not only that the Executive Steering Committee and the Torch Bearer are kept informed (and in turn the Torch Bearer will keep the board up to date), but that there is open communication with all members of the organisation, so that everyone is aware of the aims, activities and successes of the programme.

As a final thought, with the ‘clear and present danger’ of climate change upon us, it is hard to be optimistic about the future. However, it is also possible that we have a fact-based worldview of climate change and when we all work together we can hope for and look to achieve a greener world for our future generations.