Chapter 14

Thinking Strategically

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Exploring a low-cost leadership strategy

Exploring a low-cost leadership strategy

![]() Applying differentiation strategies

Applying differentiation strategies

![]() Zeroing in on a focus strategy

Zeroing in on a focus strategy

![]() Using strategy to establish your market position

Using strategy to establish your market position

![]() Coming up with your own strategy

Coming up with your own strategy

In this chapter, we help you formulate a strategy for your company that gives life to your basic mission and puts you on the road to goal achievement (see Chapter 4 to find out more about missions and goals). We introduce several basic kinds of strategy that different businesses can apply across many industries. These off-the-shelf strategies include efforts to

- Be the low-cost provider

- Differentiate your products

- Focus on specific market and product areas

We also talk about several other general strategic alternatives and answer a variety of important planning-related questions, such as these:

- What does it mean to become more vertically integrated as a company?

- What are the pros and cons of outsourcing a part of your business operations?

- How should a company act as the market leader or market follower?

Because you live and work today in a dynamic environment characterized by near constant change, we also hand out some tips on how to create a strategy built around flexibility, so that you can pivot fast to a Plan B when unforeseen circumstances suddenly hit (see Chapter 13 to get a sense of what we’re talking about).

Applying Off-the-Shelf Strategies

Maybe you think your company’s situation is absolutely unique and the issues you face are one of a kind. In the fine details, every company is different. Of course, if you look through a microscope, every snowflake is also unique (well, almost all). But snowflakes have a great deal in common when you stand back and watch them pile up outside. Companies are like snowflakes. Although all the details give companies their individual profiles, companies and industries in general have remarkable similarities when you step back and concentrate on their basic shapes.

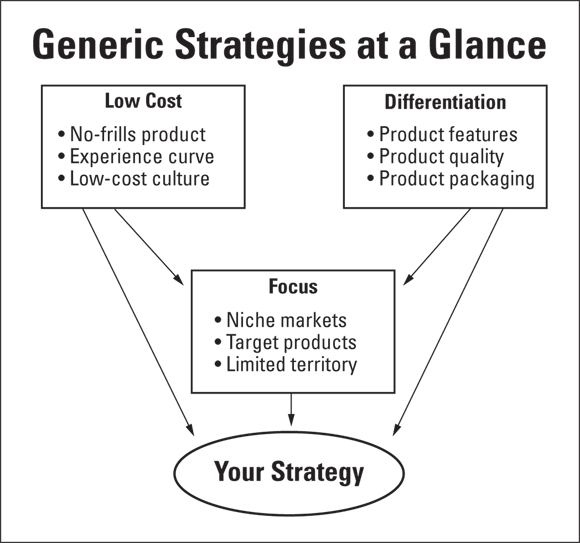

For a long time, academic observers who analyzed and reported on corporate planning defined three generic approaches to strategy. The generic strategies are important because they promised off-the-shelf answers to a basic question: What does it take to be successful in a business over the long haul? The answers, we were told, would work across all markets and industries.

- Cut costs to the bone. Become the low-cost leader in your industry. Do everything you can to reduce your costs and deliver a product or service that measures up well against the competition.

- Offer something unique. Figure out how to provide customers with unique products or a valuable service and deliver your product or service at a price that customers are willing to pay.

- Focus on only one customer group. Focus on the precise needs and requirements of a narrow slice of the market, using either low cost or a unique product to woo your target customers away from the general competition.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 14-1: Generic strategies involve deciding whether to become the low-cost leader or to provide unique customer benefits.

Cutting costs and offering something unique represent two generic strategies that work almost universally. After all, business, industry, and competition are driven by customers who base their purchase decisions on the value equation — an equation that weighs the benefits of any product or service against its price tag. (Refer to Chapter 8 for more information on the value equation.) Generic strategies simply concentrate your efforts on influencing one side of the value equation or the other.

Leading with low costs

Becoming the low-cost leader in your industry may sound pretty straightforward. In reality, it requires the commitment and coordination of every aspect of your company, from product development to marketing, from manufacturing to distribution, and from raw materials to wages and benefits. Every day you find ways to track down and exterminate unnecessary costs. Hear of a new technology that simplifies manufacturing? Install it. See a region or country that has a more productive labor force? Move there. Know of suppliers that provide cheaper raw materials? Sign ’em up.

A cost-leadership strategy is often worth the effort because it gives you a powerful competitive position. When you market your company as the low-cost leader, you call the shots and challenge every one of your competitors to find other ways to compete. Although the strategy is universal, it works best in markets and industries in which price drives customer behavior — the bulk- or commodity-products business, such as the large-scale purchase of grain, sugar, or oil, for example; or low-end, price-sensitive market segments such as those who patronize FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) limited goods retail chains such as Dollar General or Dollar Tree.

The following sections describe the ways in which you can carry out a cost-leadership strategy.

No-frills product

The most obvious and straightforward way to keep costs down is to invoke the well-known KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid!) principle. When you cut out all the extras and eliminate the options, you can put your product together on the cheap. A no-frills product can enjoy success if you can market it to customers who don’t see any benefit in (or are even annoyed by) the “bells and whistles” in your competitors’ products that drive up costs and prices — the upscale fashion house with personal shoppers at the customer’s beck and call and, of course, a glass of chilled champagne and canapes readily available.

In addition to removing all the extras, you can take advantage of a simple product redesign to gain an even greater cost advantage. Home-builder firms replaced plywood with pressed board, for example, to lower the costs of construction. Camera makers replaced metal components with plastic. And of course, you can follow the example of those hip West Coast techie firms with their cool open-space offices — which coincidentally cut down on the amount of floor space per employee and reduces the rent.

Stripped-down products and services eventually appear in almost every industry. Some obvious examples today include the following:

- No-frills airlines, such as Spirit Airlines in the United States, or Ryan Air in Europe and AirAsia in — well, you guess.

- Warehouse stores, such as Costco and Sam’s Club, which offer a wide selection, low prices, and hardly any customer service.

- Online educational providers like University of Phoenix and American Public University System, which offer college degree programs to students via digital technology — without the cost of expensive classrooms, dormitories, or rah-rah sports teams with their “fight on for old whomever” songs.

Experience curve

Companies often attain (or fall short of) cost leadership based on the power of the experience curve, which traces the declining unit costs of putting together and selling a product over time (see Figure 14-2). This is one of those concepts that apply mostly to production sector goods rather than intangibles like legal services or educational training programs. The curve measures the real cost per unit of various general business expenses: plant construction, machinery, labor, office space, administration, advertising, distribution, sales — everything but the raw materials that make up the product in the first place. The combined total of these costs tends to go down over time when they’re averaged out over all the products that you make. (You can refresh your knowledge of “economies of scale” in Chapter 5.)

There is, however, an implicit experience curve effect for intangible goods firms, such as online retailers or online securities firms selling stocks and bonds. Astute programmers in these lines of business learned long ago that building in the ability to scale a software product (that is, reproduce it exponentially at essentially zero additional cost) was often required before investors would plunk down the necessary start-up dollars. The difference was that the benefit of lower cost didn’t derive from the firm’s learning as it brought in more and more customers; rather, it was assumed that growth would occur so an ability to handle expansion was hard-wired into the original bits-and-bytes design.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 14-2: The experience curve traces the declining unit costs of putting together and selling a product as total accumulated production increases.

The underlying causes of the experience curve include the following:

Scale: Scale refers to your fixed business costs, which are fixed in the sense that the amount of your product that you make and sell doesn’t affect the costs. (Fixed costs usually include such things as your rent, the equipment you buy, and some of your utility bills.) The more products you produce, however, the more immediate scale advantage you gain, because the fixed costs associated with each unit go down automatically.

Think about widgets for a moment. Suppose you rent a building at $1,000 a month to house widget production. You add that rental expense into the cost of the widgets that you make so you don’t lose money. Perhaps you turn out only ten widgets in the first month. No matter what they cost, you have to add $100 rent ($1,000 divided by 10 units) to the price of each widget if you want to break even. But if you can boost production to 100 units the next month, you add only $10 in rent ($1,000 divided by 100 units) to the price of each widget, reducing your rental costs per unit by a whopping 90 percent. Scale is good for business and your bottom line.

Scope: Scope works a little like the scale effect, although it refers to the underlying cost benefit that you get by serving larger markets or by offering multiple products that share overhead expenses associated with business areas such as advertising, product service, and distribution. (Chapter 15 provides more information on your product portfolio.) These expenses aren’t exactly fixed, but you do gain an automatic scope advantage if the ad you run reaches a larger market or if your delivery trucks deliver two or three different products to each of your sales outlets at the same time.

We might add that economies of scope are an opportunity for service providers (as opposed to strictly tangible product manufacturers) to benefit from scale. A general hospital that offers patient services in obstetrics and pediatrics as well as general surgery and ophthalmology can use a centralized IT system, food or laundry service, and front door admission personnel to serve all the patients in the facility regardless of their specific ailment. However, a specialty health provider like a surgery center, which does no more than surgical procedures, must maintain all these services for only the limited number of patients it cares for.

- Learning: As you learn, the overall cost of doing business goes down. Remember the first time you tried to tie your shoelaces? Big job. A lot of work. Now you can do it in your sleep. What happened? The more you tied your shoes, the better you got at it. The same is true whether you work on a factory floor, at a computer workstation, or in a conference room. You (and your employees) get better at something the more you do it. And there’s another benefit here as well: Doing the same thing repetitively calls attention to the task and triggers innovation. Tying shoelaces — who does that anymore? Now just press the Velcro together to secure the fit. Moms and dads everywhere were relieved.

A general rule suggests that all these underlying causes result in what’s known as an 80 percent experience curve. Every time you double the total number of products you produce, unit costs go down by about 20 percent — or 80 percent of what they were before. This isn’t voodoo; it comes from the accumulated cost reduction from all of the above. Lots of empirical studies support this finding.

Low-cost culture

You can sustain low-cost leadership only if every part of your company commits to keeping costs under control by reducing or eliminating expenses and unnecessary spending. This kind of commitment doesn’t occur without the owners’ leadership.

Perhaps more than any other strategy and business plan that you can pursue, the push to be the low-cost leader in your industry succeeds or fails based on how well you carry it out. Knowing where and when to bring in cost-saving technology may be one important aspect of your drive, for example. But at the heart of your plan, you absolutely need to figure out how to structure the company, reward your employees, and create the spirit of a “lean, mean fighting machine.”

But be careful; sometimes the intensity of competition tempts incumbents to cross the line and seek underhanded means to avoid mutual destruction.

Standing out in a crowd

Not every company can be the low-cost leader in an industry, and many companies don’t even want to be. Instead, they prefer to compete in the marketplace by creating unique products and services, offering customers luxuries that they just have to have — products or services that they don’t mind paying a little extra for. This generic strategy is known as differentiation.

Businesses that can distinguish themselves from their competitors often enjoy enviable profits, and they frequently use those extra dollars to reinforce their unique positions in the marketplace. A premium winery, for example, earns its reputation based on the quality of its grapes and expertise of the winemaker, but it polishes that reputation through expensive packaging and promotional campaigns. These added investments make it more difficult for competitors to join in, but they also raise the cost of doing business. A maker of jug wine has trouble competing in premium markets. But at the same time, a premium winery can’t afford to compete on price alone. No company can ignore cost, of course, even if it offers something unique. Wine lovers may be willing to spend $15–$20 for a special bottle of chardonnay, but they may balk at a $50+ price tag.

- Who are my customers?

- How do I best describe them?

- What are their basic wants and needs?

- How do they make choices?

- What motivates them to buy a product or service?

Keep in mind that a differentiation strategy usually means you’re offering something at a higher price than your customer can find elsewhere. They’re not going to be willing to pay if they can’t see the difference. Check out Chapters 6 and 7 for more insights on customers. The following sections describe the ways you can set yourself apart from the competition.

Product features

You often can find the source of a successful differentiation strategy in what your product can or can’t do for customers. Some smarties out there have likened products to candidates in a hiring hall: The boss wants to hire the worker for a specific job. So what is your product being “hired” to do? A product’s features are frequently among the first factors that a potential buyer considers. How do your products compare? Are you particularly strong in product design and development? Or is the customer selection criteria based on the need for accurate order fulfillment and delivery speed? If so, you should consider how to leverage your strength in developing new features to make your company’s products stand out. (Chapters 9 and 10 help you answer these questions.)

Unfortunately, major product features represent big targets for your competitors to aim at, so differentiating your company based on major product attributes alone is sometimes hard to sustain over the long haul. Technology-driven companies — such as Apple, Google, and pharmaceutical firms — stay one step ahead of the competition by investing tremendous resources in research and development (R&D) and always offering the latest and greatest products.

Different companies create successful differentiation strategies for distinct dimensions. The auto industry is a prime example of product differentiation. The purpose of a car is to get you from point A to B. When you think of Porsche, for example, you think of performance; Volvo signifies safety; and Toyota and Honda are energy-efficient, reliable choices. Tesla indicates environmental concern. These differences allow competitors to prosper in the same industry, each in its own way, even though their products all do essentially the same thing.

Competition is a bit different in service industries. For one thing, you have to face the importance of customers’ impressions when you deal with services. By definition, a service is something you can’t physically hold; you can’t touch it, feel it, or kick its tires. So customers face a bit of a quandary when it comes to making well-informed decisions. Figuring out what is and isn’t a quality service is harder. How do you know whether your doctor is a genius or a quack, for example? Is the pilot of your flight an ace or just so-so?

Based on this lack of insider information, customer perception dominates the service industry. When customers don’t have all the data, they go with what they can see. No matter what other dimensions are important, the tangibles — equipment, facilities, and personnel — play a significant part in a customer’s perception of service quality. They look for any clues to either confirm or deny a priori beliefs and attitudes. This is especially important if your market offering is a one-time experience, like a college education, a coronary bypass operation, or a bucket-list vacation. Perception is everything.

Product packaging

Customers often look beyond the basics to make the final decision on what to buy. In fact, your packaging may influence customers as much as the standard set of features that your product or service offers. You can’t judge a book by its cover, as the saying goes — but many people buy books simply because of that cover. Remember those universities noted earlier in this chapter? Today college administrators are adding expansive food courts in the dorms and upgrading the sports stadium to professional level standards. It’s like dressing up the diploma.

You can develop an effective differentiation strategy based on product or service packaging — how and where you advertise, what warranties or maintenance agreements you provide, and where you decide to sell your product or service.

With creative advertising, attentive service, and sophisticated distribution, you can make almost any product or service unique in one way or another.

Focusing on focus

The two generic strategies we talk about in the previous two sections concentrate on one side of the customer value equation or the other (check out Chapter 8 for more value equation info). A cost-leadership strategy points out the price tag, and differentiation emphasizes the unique benefits that a product or service offers. The final generic strategy plays off the first two strategies: A focus strategy aims at either price or uniqueness, but it concentrates on a smaller piece of the action.

A focus strategy works because you concentrate on a specific customer group. As a result, you do a better job of meeting those customers’ particular needs than your competitors who try to serve larger markets. The following sections discuss several ways to concentrate your efforts.

Niche markets

If you’ve traveled to nations that are struggling to move up the economic ladder, you may have noticed that many products and services you find there are basic commodities, without much variety or choice. This is not because people living in those lands don’t want a broader selection. It’s due to the fact that low income levels and a lack of communications and distribution infrastructure makes it difficult for sellers of upscale goods to survive. In many product and service categories, it’s a one-size-fits-all market.

Countries with large populations in which household incomes are spread over many levels create opportunities for the diligent business planner to find niches. These nations typically enjoy modern communications technologies, such as TV and the Internet in addition to radio stations. This allows for relatively easy access to large numbers of people, so that the planner can slice and dice markets into countless shapes and sizes and target a relatively small group. For example, KingSize is an online seller of men’s apparel — but targeted to those who are greater than 6'2″ in height and 225 pounds in weight, a group of 13 million that is less than 4 percent of the U.S. population. And then there’s so-called one-to-one marketing, in which sellers are able to pinpoint just a tiny fraction of potential customers and give them precisely what they’re looking for.

Limited territory

A focus strategy works especially well for the new kids on the block who want to establish a foothold in an industry in which the big guys have already staked out their claims. Instead of going after those fat, juicy markets (and getting beat up right away), you can avoid head-on competition if you focus on smaller markets, which may be less attractive to existing players. After you establish yourself in a niche market, you may want to challenge the market leaders on their own turf. Motel 6, for example, started out as a small regional chain that offered clean beds and private baths at bargain-basement prices. Now the company is a major player in the motel industry — and, of course, attracted others who saw success and said “I can do that, too.” While we’re not yet aware of any Motel 1s, this is what competition is all about. (Actually, we are aware of Motel 1s; ever been around a college campus?)

For small, established companies in a market, a focus strategy may be the only ticket to survival when the big guys decide to come to town. If your company has few assets and limited options, concentrating on a specific customer segment gives you a fighting chance to leverage the capabilities and resources that you have.

Changing Your Boundaries

Generic strategies form the basic building blocks that you can use to start assembling your company’s business plan (see the section “Applying Off-the-Shelf Strategies” earlier in this chapter). But building blocks are just the beginning. Strategy should also address all the fine details that make your company and its goals unique. How do you take the next step? A successful strategy and plan depend on your business circumstances — what’s happening in your industry and marketplace and what your competitors are up to (see the example of Kohl’s in the nearby sidebar). These factors often determine what strategy can best serve your company.

The evolution of new strategic models

The historic changes that began to reshape business and commerce throughout the world at the end of the 20th century offered both threats and opportunities for many large firms that were “vertically integrated” — that is, they chose to handle in-house all aspects of their business from A to Z. But rapid innovation of new products and services meant that many of these firms that tried to be all things to all comers were finding it difficult to be the go-to supplier for increasingly demanding customers. As a result, companies began to establish strategic alliances with companies that had complementary products that customers wanted, rather than attempting to make them everything in-house. Take a look at Chapter 16 for our description of the new “dynamic capabilities” model of strategy that addresses these concerns. Meanwhile, consider what IBM did.

Since the beginning of its production of computers in the 1950s, IBM had insisted on a strategy of vertical integration: mainframe processors, memory cards, terminals, CRTs (the visual display monitor), keyboards, printers — everything came from this one giant firm, and most of these goods were made in large manufacturing facilities in Poughkeepsie, New York. But when it entered the PC (personal computer) segment in the early 1980s to compete with new upstarts like Apple, IBM realized that its complex and bureaucratic structure would probably mean years of development time before it had a competitive product. It consequently moved all manufacturing for PCs to Florida, partnered with a small and unknown software developer in Seattle named Microsoft to provide the operating system (OS), and contracted with Intel in Silicon Valley to supply the microprocessors that powered these machines.

Rapid innovation of new products, their complexity, and high costs have caused many firms to create ecosystem partners to bring together all of the necessary ingredients to satisfy choosy customers who are far more knowledgeable than in the past. These firms began to realize that customers today want the best solution to fix their problems, and not necessarily a single brand to do it. Some verbal gymnasts have called the practice “co-opetition.” In the tech world, one variant is called the “platform economy,” whereby a company creates a digital means — an online site — to bring parties together, and takes a tiny sliver of revenue from each transaction (kind of like a dating site for nerdy firms).

Outsourcing and offshoring

Global competition has touched nearly every market in every corner of the world. One result is that companies had to find new ways to compete with products coming from nations with lower costs, such as labor, allowing those offshore suppliers to offer lower prices. By now it’s conventional wisdom that domestic firms need to streamline operations, transforming themselves into leaner and meaner tigers if they want to survive in the global jungle. One strategy that became popular as a way to do this was to outsource certain activities in the value chain (see Chapter 10 for details on value chains). Outsourcing was a rediscovery of the old “make-or-buy” idea: Do the job yourself in-house — make — or turn to an external source to handle the task — buy. With globalization this extended into offshoring, with external suppliers located in countries like Mexico, China, India, Vietnam, and numerous others.

In each case, the idea is to take a piece of your business operations — your payroll system or your computer support, for example, or the production of a major component or even the entire manufacturing process — and hire an outsider to do it for you to save you money. This decision obviously implies that you have taken steps to ensure that quality is not compromised. But the benefit is that outsourcing can help you do what you do better. When you no longer have to worry about certain parts of your business, you can focus your energies on the operations that you do best and the activities that set you apart from the competition.

Leading and Following

No matter what industry you’re in, you can divide your competition into two major groups: the market leaders and the market followers.

- Market leaders are top-tier companies that dominate the marketplace, set the agenda for the industry, and make things happen; they occupy the driver’s seat.

- The market followers, well, follow along. They’re not always small, by the way. Because of history, tradition, or whatever, they have chosen to let others go first. These companies still work hard and think big, and if they sometimes don’t play follow-the-leader, then the front-runner might have to pull back.

Depending on the market situation, companies in both groups behave very differently. Whether you already operate as part of an industry or you want to join one as a new business owner, you need to understand what motivates both the market leaders and the rest of the pack. The following sections explore some market strategies that focus on industry position.

Market-leader strategies

Market leadership varies, from the absolute dominance of one company to shared control of the industry by several leading players. If you enjoy a spot among the leaders, look at these possible strategic approaches. It’s kind of like playing offense, playing defense, or keeping the score tied:

- Full speed ahead: In this situation, your company is the clear market leader. Even so, you should always try to break farther away from the pack. You should strive to make the first move, whether you implement new technology and introduce innovative products or promote new uses and set aggressive prices. You should not only intend to stay on top, but also want to expand your lead.

- Hold the line: Your company certainly ranks high in the top tier of the market, but it doesn’t have the commanding position of strength in the industry, so your goals center on hanging on to what you currently have. Those goals may involve locking distributors into long-term contracts to make it more difficult for customers to switch to competing brands or going after new market segments and product areas to block competitors from doing the same thing.

- Steady as she goes: In this case, your company is one of several powerful companies in the market. As one among equals, your company takes on part of the responsibility of policing the industry to see that nothing upsets the boat. If an upstart challenger tries to cut prices, you quickly match those lower prices. You always scan the horizon for new competitors, and you work hard to discourage distributors, vendors, and retailers from adding new companies and brands to their lists.

Market-follower strategies

Market followers often take their cues and develop strategies based on the strength and behavior of the market leaders. An aggressive challenger, for example, may not thrive in an industry that has a powerful, assertive company on top. Fortunately, you can choose among several strategic alternatives if you find yourself in the market-follower position:

- Make some waves. Your company has every intention of growing bigger by increasing its presence in the industry, and you’re willing to challenge the market leadership head-on to do it. Perhaps your strategy includes an aggressive price-cutting campaign to gain market share. Maybe you back up this campaign with a rapid expansion of distribution outlets and a forceful marketing effort. The strategy requires deep pockets, commitment, and the skill to force a market leader to blink, but in the end, your efforts could make you the leader of the pack.

- Turn a few heads. Your company enjoys success in its market niche, and you want it to stay that way. So although you don’t want to challenge the market leadership directly, you fiercely defend your turf. You have strengths and advantages in your market segment because of your product and customer loyalty. To maintain this position, you focus on customer benefits and the value you bring to the market.

- Just tag along. You can easily point out companies that have settled into complacency. Frankly, they usually operate in rather boring industries where not much ever happens. These companies are quite pleased to remain toward the end of the pack, tagging along without a worry. Don’t count on them to do anything new or different in the marketplace. (If you find your company in this position, you may be quite happy to tag along, too. If not, you should think about making a change while you’re still awake.)

We are sad to report that the XYZ Company unfortunately died last month after x years of service to its customers. The cause of death was ______________. The attending physicians stated that the firm might have been able to avoid this unfortunate fate if it had done the following: ___________.

We either ask each participant to complete their report individually (giving them 20–30 minutes to do this), or we place participants in small groups of 3 or 4 and give them 60 minutes. The participants then re-group, and each presents the results of their obituary, followed by a general discussion. We have found this to be a sobering experience that forces company leaders to probe deeper into what strategic problems they might have, and to consider steps to overcome them. Perhaps this is an exercise that might fit your organization as well.

Tailoring Your Own Strategy

Coming up with the right strategy is something that you have the chance to work on over and over again — rethinking, revising, and reformulating. If you approach strategy in the right way, you don’t ever finish the task.

As you begin to shape your strategy, let the following pointers guide you:

- Never develop a strategy without first doing your homework.

- Always have a clear set of goals and objectives in front of you.

- Reflect on your assumptions and make sure they reflect reality.

- Build in flexibility and always have an alternate strategy.

- Understand the needs, desires, and nature of your customers.

- Know your competitors and don’t underestimate them.

- Leverage your strengths and minimize your weaknesses.

- Emphasize core competence to sustain your competitive advantage.

- Make your strategy clear, concise, consistent, and attainable.

- Trumpet the strategy so you don’t leave your organization guessing.

If you’re a seasoned business planner, you already realize the need to create a strategic blueprint for your business. You can’t have something as important as this simply sloshing around your overcrowded brain, hoping you don’t forget the important parts. You should include a summary of your strategic blueprint in the “

If you’re a seasoned business planner, you already realize the need to create a strategic blueprint for your business. You can’t have something as important as this simply sloshing around your overcrowded brain, hoping you don’t forget the important parts. You should include a summary of your strategic blueprint in the “ This is one reason why online product/service customer evaluations by prior users have become so popular with shoppers. They want guidance. Lo the firm that generates a gaggle of negative reviews and does nothing in response.

This is one reason why online product/service customer evaluations by prior users have become so popular with shoppers. They want guidance. Lo the firm that generates a gaggle of negative reviews and does nothing in response. In our consulting and training work with a wide variety of firms in many industries, we have often used a little exercise as a way to focus key leaders on what might be a problem with their strategy, and what to do about it. We ask each participant in the program to prepare a one-page obituary for the company. Yes, you read that correctly. We ask them to start as follows:

In our consulting and training work with a wide variety of firms in many industries, we have often used a little exercise as a way to focus key leaders on what might be a problem with their strategy, and what to do about it. We ask each participant in the program to prepare a one-page obituary for the company. Yes, you read that correctly. We ask them to start as follows: