Step 1: Stand for Something: Agree on Purpose and Principles

Helena Gottschling had been working at the same organization for more than three decades when they decided to make the fundamental shift toward flexible work. Gottschling is the Chief Human Resources Officer for the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), an institution with a long history dating back to 1864. It has more than 86,000 employees worldwide serving an excess of 16 million clients.

It was feedback from employees that first caused RBC to consider this shift. During the pandemic, when so many people were working remotely, they did a series of surveys, focus groups, and town halls across the globe, out of which came a clear message: The vast majority of their employees appreciated the personal benefits of flexible work. That dovetailed with the main business purpose for RBC, which was to gain a competitive advantage in the battle for talent. “We're in a very competitive marketplace for talent,” Gottschling says. “If done right, we believe flexibility could be a true differentiator.”

Flexible work options, while available, were not widely used across RBC before the pandemic, so what they were contemplating was a real sea change for the company. One of their first steps was to create what they called their “enterprise principles.” This was particularly important because of the global diversity of the company: RBC is a complex organization with multiple lines of business spanning 36 countries. They needed principles to help guide the right decisions and drive behavior change across the organization. “The nature of the work across our various businesses is very different, so we knew out of the gate that we couldn't push out a one-size-fits-all solution,” Gottschling explains. Someone working in personal banking, for example, might have to be on hand to meet with customers, whereas someone working in analytics or accounting would have very different requirements. Their principles—five in all—set a foundation, helping to create alignment across the large, diverse, and geographically dispersed organization and guide leaders in determining what's best for their respective businesses.

Getting to a place where they could distill their own vision of flexibility into five simple, easy-to-understand principles that applied to the entire organization was a process—one that involved lots of discussion about how to tailor some of the best practices of flexible work to the specific needs of their business. For example, when RBC launched their flexible work strategy, they focused on both schedule flexibility and location flexibility, but with some boundaries. They decided that, for their organization, “Proximity still matters” (Enterprise Principle number three). That doesn't mean employees have to be in the office five days a week, but similar to how “Digital-First does not mean never in person” at Slack, RBC's leadership recognized the importance of bringing people together every now and then in intentional ways (something we'll discuss in greater detail in Step 5). “Proximity still matters” communicates to the organization that it's important to RBC that people are generally located close enough that showing up once a week—or maybe a week at the beginning or end of each quarter, depending on what works for their team—is an option for meetings, events, or simply to plan and connect with colleagues.

“What we didn't want,” Gottschling says, “is to have one group say that all their team members could move to a different region and never come into the office while another group that does similar work says the complete opposite.” You'll note that “Proximity still matters” doesn't dictate that people need to live in a certain region or city. Instead, Gottschling points back to employees to make the decision by asking “What's your tolerance for commuting?” based on the team's frequency of in-person gatherings. You can see how this specific principle helps to provide a balance between flexibility and structure—something that both leaders and employees say they want.

Early feedback on their flexible work strategy has been positive, and the company has been using it in recruiting materials, like their “Why RBC?” aimed at potential new employees. There are some skeptics in their ranks, but when doubts arise Gottschling likes to remind people that they worked remotely for at least 18 months during the pandemic and they didn't skip a beat. That doesn't mean there isn't more work to be done to ensure their strategy is successful.

“We're going to learn as we go, keep having conversations about what works and what doesn't, and we're going to get better at it,” Gottschling says. They will make adjustments along the way, but she believes flexibility is here to stay. And she's leading by example: “I will never, personally, go back to five days in the office every week.” And, she projects, neither will most of their people.

Just like with RBC, the process of creating your flexible work purpose and principles at the leadership level—which is what you will learn to do in this step—is how you will start to gain the understanding and alignment necessary to drive an organization-wide change in how your people work together.

Your Flexible Work Purpose: What's Your Why?

Flexibility, especially schedule flexibility, will only succeed if you are willing to set aside outdated conceptions of how work should be done and think differently. But with so many different ideas about what flexibility can mean to each person, team, and company, it can be hard to band together and create this kind of shift. You should start by understanding your purpose and aligning leaders around it: WHY do you want to enable flexible work in the first place?

Why start here? Because too many organizations have jumped into defining a flexible work strategy without understanding why they're implementing it, other than the fact that their employees want it or they want to keep up with peer companies who are already doing it. This is a flawed approach for a couple of reasons.

First, as we know from research, companies with a clear purpose have an advantage. Increasingly, employees—especially younger ones—say they want to work for purpose-driven organizations that can clearly articulate how they serve their people, customers, and community. These kinds of companies perform better, too. A global Harvard Business Review study found that companies with a clearly articulated purpose had higher growth rates. They were also better able to innovate and transform—capabilities that are crucial in today's competitive marketplace. As one executive in the study put it: “Organizations do better when everyone is rowing in the same direction. A well-integrated, shared purpose casts that direction. Without the shared purpose, organizations tend to run in circles, never making forward progress but always rehashing the same discussions.”1 The same could be said about taking a purpose-driven approach to anything as fundamental to your business as how work should get done.

Second, as we explained in the last chapter, flexible work can mean a variety of things. If you did a Google search in 2021, as companies were figuring out how to move forward after pandemic-imposed restrictions eased, you would have seen everything from “going back to the office full time” (Goldman Sachs) to “working two-to-three days in the office” (many Fortune 500 companies) to “fully remote” (Gitlab) and “virtual first” (Dropbox). You would have found companies that were focusing only on a Work From Home (WFH) policy, and others that were offering not just location flexibility, but the kind of schedule flexibility that a greater number of workers really want and that is inherent in the Digital-First approach that we recommend.

To move forward, your leadership team needs to talk through the real business purpose behind flexible work. After all, this isn't just something you do to make your people happy. It can have a real impact on your bottom line. Purposes may vary somewhat from company to company, but they all generally come back to addressing one key issue: talent. As we touched on in the last chapter, flexible work helps companies attract top talent. It allows them to recruit from a larger pool of candidates. It helps them engage and retain the talent they already have. As you have seen already, RBC's purpose for flexible work was to address the needs of their current employees, who valued flexibility, and to be a differentiator in a highly competitive marketplace for talent—which is compatible with their overall business purpose of “helping clients thrive and communities prosper.” There may be additional, often secondary, reasons for a flexible approach—like allowing more agility and connection among a global workforce or an initial savings on real estate costs—but your main Flexible Work Purpose will almost surely center on your people.

At Slack we touched on similar themes when defining our purpose. After much (often messy) debate over the course of several months, we articulated our purpose through a set of key questions and beliefs that the leadership team needed to agree on:

- Do we want access to the best, most diverse talent pool that exists? There's a giant pool of talent that today is inaccessible to us because unless someone lives within commuting distances of our offices, we didn't hire them.

- Will employees continue to demand flexibility as a basic benefit? In the same way compensation is market driven, work-from-home policies, flexible schedule policies, and a Digital-First approach are going to be expectations that employees demand.

- Do we want the agility that comes with being Digital-First? The ability to collaborate across cities and suburbs, time zones, and around the globe; the removal of the barriers of “remote offices” being second class; and the speed that comes with shared knowledge and understanding of goals all are better served by a Digital-First model over office-centric.

It's in those often messy debates about how flexible work will support your business objectives that you begin to build alignment among your leadership team. You will then continue to build it as you take that purpose and translate it into a set of core principles that will help you to introduce your flexible work strategy and align the rest of your organization around it.

Your Flexible Work Principles: How Can You Support Your Purpose?

Principles don't look too different from core company values in some ways. They're not focused on the tactical how (like how many days you should be coming into the office), but more on the mindset required to make a significant shift in how you do business.

You already saw RBC's principles, which cover:

- Their overarching intention: “Flexible work is here to stay.”

- How they're approaching the shift: “Starts with our business strategy.”

- Three main things they care about when considering what flexibility means to them, and how they want flexible work to play out in their organization: “Proximity still matters,” “Strategic investment is required,” and “Inclusive culture with growth opportunities.”

Principles are meant to be shared across an organization in order to provide direction, consistency, and inspiration as people make the big changes required to enable flexible work. Think back to the example of RBC: The bank has multiple business units across numerous countries. They have a wide variety of functions and tens of thousands of employees, all with unique needs. How do you create a flexible work strategy that can accommodate all that?

The answer is that you “don't push out a one-size-fits-all solution,” as Gottschling put it. Instead you allow for flexibility in the execution of your strategy, and you enable individual department and team leaders to decide what works best for their group—but within a framework and with top-level guidance. Your principles act as a kind of North Star. Any decision that gets made at any level—about how often a team will meet, for example, or how to measure team or individual success—should be consistent with those principles.

Principles are also meant to help people begin to think in new ways. You have to always remember that flexibility upends traditional ideas about how work is supposed to be done, ones that date back far longer than the careers of anyone reading this book. Redesigning work and replacing old notions with something new and better will take time and reinforcement. It's another reason why spending the time up front to create clear and considered principles is so important. They provide your people with that North Star, that anchor, as they go about changing not just how they do their work, but how they think about it as well.

Some principles will be unique to your business, like RBC's “Proximity still matters.” Contrast that to the many companies that have gone in the opposite direction by instituting “work from anywhere” policies that allow employees to relocate to an island in the South Pacific if that's what they choose. Open source software company Gitlab, for example, is fully remote with no corporate headquarters at all, so they would have different requirements.2 Your principles should marry your flexible work strategy with the overall needs and objectives of your business.

That said, we have found that many principles are pretty universal across different organizations and industries. (See the sidebar for some examples.) One is to “Ensure equitable access.” This is such an important one that we devote the next step to it. What's key to know now is that flexible work is meant to enable your people to do their best work. You undercut that if people feel like they lose access to knowledge within the company, opportunities for advancement, or a sense of community and camaraderie with coworkers if they don't show their faces in the office. It's not enough to simply say, “You can work from home if you want to.” You have to make sure that working from home doesn't make people feel like second-class citizens.

We're going to talk more about how you can start the process of defining and aligning around your flexible work purpose and principles in the next section. But before we do that, there are a couple of useful hints to keep in mind when articulating your principles:

- Provide context: Your principles should help your people envision what flexible work will look like and understand what matters most when putting it into practice.

- Keep it simple: Don't overengineer this. RBC has five principles. Most companies have between three and six. It's up to each business to decide what's most important to communicate, but the more complicated you make it, the harder it will be for your people to appreciate your vision.

You'll find further guidance on how to create your purpose and principles in the toolkit at the back of this book (see “A Simple Framework for Creating Your Flexible Work Purpose and Principles” on page 180).

The Process: How Leaders Can Start to Create Alignment

Even something that sounds straightforward, like defining your purpose or principles, can be a messy endeavor when you start talking about it among different people with differing opinions—as anyone who has ever tried it will know. We've been through a flexible work transformation at Slack, and we have worked with numerous companies as they've done the same, so we know what it's like. From those experiences we've distilled some best practices that will make your discussions a little less messy, providing focus and structure as you start defining and aligning around a purpose and principles that will guide this fundamental shift and continue to drive the change going forward.

The following sections will walk you through six ways to start creating leadership alignment around flexible work:

- Start with the right orientation

- Check your assumptions

- Dedicate resources

- Involve your people early

- Lead with transparency

- Keep a “more to learn” mindset

Start with the Right Orientation

When you start your conversations to align on a flexible work purpose and principles, keep in mind that organizations that are successful at this have a common orientation. They've made the conscious decision that they're not going back to old ways of working that really don't make a lot of sense anymore. Instead they have stated their intention to move forward with an understanding and appreciation of how much has changed and how it's time that notions of work caught up to those changes.

When defining our flexible work principles at Slack, we began with one that speaks to this very idea: “We aren't going back; we're moving forward, with all that we've learned.” That principle grew out of disagreements that took place among our leadership team about how (and if) we should return to the office once pandemic restrictions were lifted. As we debated the topic, some leaders expressed a desire to return to how things were. That was when our then Chief People Officer, Nadia Rawlinson, asked a question that really hit home about whether we wanted to go backward or whether we wanted to move forward.

In our talks there were real questions about whether going back was even possible now that so many people had experienced, and appreciated, a new way of doing things. There was also concern that if we tried to, we'd be missing a real opportunity. As our CEO, Stewart Butterfield, put it: “We had a once in a lifetime opportunity to reinvent the way we worked—for the better.” We decided we didn't want to waste the opportunity.

We made that clear to everyone in our company by making it principle number one. When we published our principles, we also expanded on it and included the following context:

The Change Must Be Leader Driven

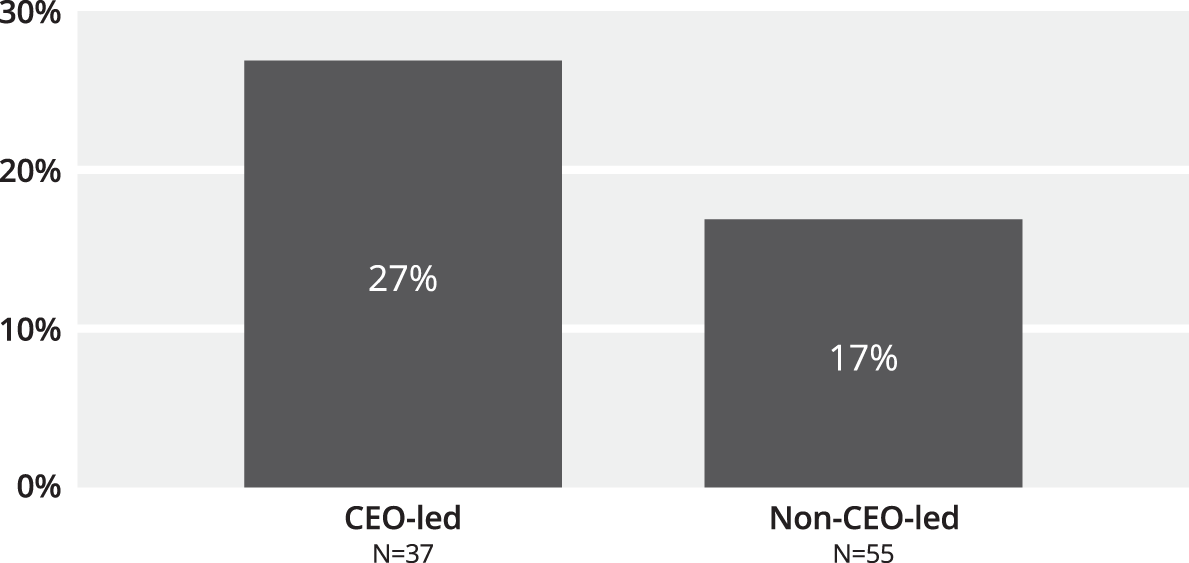

The question of how people will work together is so fundamental to any business that a move toward flexibility must be driven by top leaders—preferably the CEO. In fact, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) was able to measure the importance of CEO participation in their Future of Work survey. It found that flexible work strategies that were CEO-lead progressed faster than those that weren't (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The percentage of companies that are experimenting with new ways of working, CEO-led vs non-CEO-led

Source: Boston Consulting Group CEO survey, June 2021. Options: Not started, Early Stages, Well Along, Experimenting.

At Slack the change to flexible work started with dedicated time and attention from our CEO and executive team, including weekly dates on the calendar for in-depth conversations. Those conversations largely centered on three main questions that can provide a starting point for any organization:

- What problems are we trying to solve?

- What business outcomes do we want to achieve?

- What perceived challenges are we facing?

The team was largely starting from scratch because much of the research and examples we're including in this book didn't exist yet or hadn't been widely published. It took more than two months of conversations to agree on a purpose and come up with a set of principles that were ready to be shown to the rest of the organization. It may seem like a lot of time spent up front, but it was worth it because of the alignment we were able to build as a result.

Check Your Assumptions

What came out of those executive conversations at Slack—and what we hear over and over again from the organizations we work with—is a common set of concerns among top leaders about how, and even if, flexible work can really work. Following are some of the ones we hear most often:

- How will I know my people are actually working and being productive?

- What will happen to our culture if we aren't in the office?

- Won't it hamper our ability to innovate and be creative?

- Won't new and younger employees be left behind with fewer opportunities for apprenticeship and learning?

When you hear them, or if you think of them yourself, it's a good opportunity to check your instincts and ask why you believe that flexible work will have the kind of negative impact that these questions imply. We have talked already about how many of these concerns aren't rooted in data. Flexible work has been linked to higher productivity, not less, for example, and doesn't negatively impact creativity based on Future Forum research.

Gottschling says she gets asked these kinds of questions at RBC, too, and she has a useful way of addressing them. When she's asked how managers will know if someone's actually working, for example, her typical answer is: “How did you know they were working when they were in the office?” You will know your people are being productive if you set clear goals, check in with them regularly, and pay attention to the results they get. These are things any good manager should be doing no matter where someone works. As Gottschling points out, “Frankly it's no different. It's not like you are looking over their shoulder to see what they are doing on a day-to-day basis in the office either.”

In fact, her tactic of answering a question with a question is a useful one for addressing all these concerns:

- How will I know my people are working and being productive?

- How did you know they were productive before?

- What will happen to our culture if we aren't in the office?

- Why do we need an office to create culture?

- Won't it hamper our ability to innovate and be creative?

- Why do we believe the office is required for innovation and creativity?

- Won't new and younger employees be left behind with fewer opportunities for apprenticeship and learning?

- Who did office-based learning work for the most, and why do we think it's the best way to learn?

So you don't think we are simply dodging these common questions, we assure you we will address each one in more detail in later chapters. We bring them up here to show the importance of checking your reflexes from the start—to become more conscious of default ways of thinking that may get in your way.

To put it more broadly, ask yourself why you believe people need a fixed schedule in the first place. Or, why do any of us need to be available eight hours a day for meetings? If your answer is because we've always done it that way, then it really is time to examine your thinking. After all, just because something worked in the past doesn't mean it will work in the future. And it doesn't mean there isn't a better way to do it right now—a way that can lead to even better results.

Dedicate Resources

A fundamental shift like this one isn't going to work if a company simply puts out the purpose and principles and leaves it at that. It will take time, investment, and long-term accountability to make something like this work. It will also require a shift in how you think about allocating some of your resources, so that needs to be part of your leadership discussions.

For example, instead of looking at flexible work as something that will require a big, new investment, think about it more in terms of reallocating resources. All that time and money you once put into your real estate portfolio and office layout—figuring out who got what office and which departments went on which floors to enable collaboration—can now be shifted toward determining which digital tools and infrastructure will best enable those collaborations. Investments in many of the perks you once offered to attract top talent—like in-office restaurants and gyms—can be redistributed to individuals to use in ways that will best serve them and their work.

You will also have to rethink some of your people resources. There must be people focused on making flexible work successful, and not just through the transition, but over the long-term as well. At Slack we formed a dedicated “Digital-First task force” composed of senior members across geographies and functions (HR, communications, IT, etc.), as well as core teams that are responsible for the work to move us forward. They worked directly with Slack's executive team for support, feedback, and ultimately, implementation of new policies. Some companies are even creating a new role, a Flexible Work Leader, because like anything in business, if someone isn't accountable, it probably isn't going to work.

Involve Your People Early

A Future Forum survey of remote workers found that more than two-thirds (68%) of executives want to work in the office all or most of the time—that's three times the number of non-executives who said the same.3 Remember, employees have a clear preference for flexibility: 93% want schedule flexibility.

There's obviously a disconnect here between executives and employees. What's driving it? Future Forum's survey looked at that too, and one of the main culprits is the fact that the two groups have very different experiences of work. Executives have a 62% higher rate of satisfaction than employees. They also report a better work-life balance (78% better) and a better ability to manage stress (114% better). These numbers aren't all that surprising when you consider the fact that executives tend to have stronger networks, more autonomy, and better access to resources like space and childcare that support their work. In essence executives have always had more flexibility in their work, so their need for a company-wide policy supporting it is far less.

You won't be able to bridge this disconnect unless you get feedback about your flexible work plans from people at all levels of your business—and you get it early. At Slack we created advisory groups with employees representing different regions, employee resource groups, and functions to get input about different aspects of our strategy or potential points of failure. RBC also made a point of bringing in multiple perspectives. “We often think about our work preferences and the experiences we had growing up in the bank,” Gottschling says, “but you really have to think about it through the employee perspective. I often remind leaders that they are simply a focus group of one. What we really have to guard against is projecting our personal preferences into the actions we take.”

Lead with Transparency

This guidance goes hand in hand with what we just covered. A flexible work strategy is about enabling your people to do their best work, so your people need to understand it. They need to know your why—the purpose behind the changes you're making—as well as what those changes will look like and how they will be impacted. But organizations often miss the mark in creating this kind of transparency. For example, Future Forum's survey revealed another big disconnect within organizations when we asked executives and non-executives about post-pandemic reopening plans. Two-thirds of executives believed they were being transparent about their plans while fewer than half of employees agreed. And employees who don't believe their employers are being transparent report substantially lower job satisfaction, and are far more likely to be open to new opportunities outside their company.

One of the main reasons we started in this first step by asking you to define your flexible work purpose and principles is not just to get alignment among your executive team. It's so you have something to show to your entire organization. It's a way to begin communicating broadly and build greater alignment. It's also a way to open up conversation about your plans. We will come back to the concept of transparency and communication throughout this book because it's crucial to creating change—any change, really, but especially the kind of fundamental, organization-wide change we're talking about here. Transparency is what allows you to build trust with your people, and you're going to need that trust to do something as big and bold as redefining the way you work.

Keep a “More to Learn” Mindset

Finally, you can continue to build trust through transparency by admitting up front that your flexible strategy is a work-in-progress and you don't have all the answers. Starting with those first conversations about your purpose and principles, and continuing as you hone your strategy and put it into practice, your company will be best served by keeping an open mind and a willingness to learn. This is a new way of operating for most companies, so you will need to try things out, pay attention to what works, and be willing to adjust and adapt. Business isn't stagnant, as we all know, and your flexible work strategy should grow and change with the changing needs of your business. As Gottschling said about RBC's plans: “We're going to learn as we go, keep having conversations about what works and what doesn't, and we're going to get better at it.”

Notes

- 1. Keller, V. (2015). ‘The business case for purpose’, Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/digital/ey-the-business-case-for-purpose.pdf (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 2. Pendleton, D. (2021). ‘CEO who built GitLab fully remote worth $2.8 billion on IPO’, Bloomberg, 14 October. Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/companies/ceo-who-built-gitlab-fully-remote-worth-2-6-billion-with-ipo/ar-AAPw2db (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 3. Sarasohn, E. (2021). ‘The great executive-employee disconnect’, Future Forum, 5 October. Available at: https://futureforum.com/2021/10/05/the-great-executive-employee-disconnect/ (Accessed: 18 November 2021).