CHAPTER FOUR

EMBEDDED FINANCE IN THE OFFLINE WORLD

Embedded finance's suitability for online transactions and digital businesses was discussed in Chapter 3, but now we turn our attention to the world of brick-and-mortar businesses, which is probably the most exciting iteration of what embedded finance can offer. In 2019, Angela Strange, general partner at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, announced: “In the not-too-distant future, I believe nearly every company will derive a significant portion of its revenue from financial services.”

Bain Capital Ventures’ Matt Harris agrees. Strange didn't just mean Google and Apple. The ongoing Covid pandemic and the accompanying restrictions on activity placed severe stresses on offline businesses, but in the summer of 2021, with Covid still ongoing in most of the world, brick-and-mortar business still counted for 75% of retail transactions in the US. In Europe, the numbers are similar, with about two-thirds of retail transactions in 2021 taking place offline.1

A LOOK INTO THE FUTURE: THE SUPER APPS

It is no secret that China is well ahead of the West when it comes to having their life fully embedded into apps such as Alipay and WeChat. When asked what the day-to-day life of a person living in China powered by embedded finance looks like, Yassine Regragui, fintech specialist and expert on China, refers to his own experience:

During my six years living in China, I never had to withdraw cash or use my bank card to pay, I only used Alipay or WeChat. I was a foreigner living in China, but could experience these two apps the same as a Chinese citizen. Ever since I connected my bank card to these apps, everything was possible. So what is possible with these apps? We can, of course, make in-store payments using QR codes. We can also make online payments. We can use insurance. We can have microloans. We can have investments, products, etc. But more than 50 percent of the time, we do not use the app for payments, instead we use it to book a cab, use public transports, talk with our doctors, communicate with our friends, rent an apartment, even formalize a marriage by signing such agreements within the app. So the possibilities are limitless. Also, all Chinese administrative services are provided on these apps. For example, the Chinese government relied on these two apps to initiate the COVID QR codes to allow citizens to move freely when they didn't have some symptoms. On Alipay alone, there are more than 1000 features. Over one billion people in China are using those apps. So it means that there is a kind of value they get from it and that makes their life more convenient.

The question is: how does the rest of the world get to this level of embedded finance simplifying the lifestyle and life events of their citizens at the point of context, when they most need it?

THE DATA PLAY

Businesses with a digital presence are ideally suited to benefit from embedded finance because they have a great deal of customer data at their disposal. This data allows the business to predict future needs for the customer, to offer relevant deals and pricing for them based on those predictions, but also gives them the ability to offer a fairer and more tailored interest rate when it comes to providing them with a credit facility if they so chose to do so. Today, even offline merchants such as retailers include a digital component to their businesses and embedded finance can help them supercharge their customer's experience. Shoppers are asked for email addresses and phone numbers as ways to communicate rewards and boost loyalty. This will be discussed in more detail later, but for now we note that just as few businesses are truly “online-only” today, few businesses are also “brick-and-mortar-only.”

Financial institutions can see a great deal into customers’ lives, and receive strong indicators of life events. Still, in general, they have largely failed to predict customer needs and offer the right products at the right price at the right time due to outdated systems and processes. They can see which stores and brands merchants’ customers spend the most money at frequently, how often they shop there, and how much they spend in each transaction, but crucially, they cannot see what specific products the customers are actually buying. The concept of what consumers are actually purchasing is often known as Level 3 data.

Let's discuss the three levels of data for a moment:

- Level 1 data is the merchant, or store, name and transaction amount.

- Level 2 data includes the merchant location, tax ID, and sales tax amount.

- Level 3 data includes the item description and quantity. Only merchants typically have access to Level 3 data.

This asymmetry of information is what puts so much potential power into the hands of merchants, especially those that customers trust and visit repeatedly. Merchants may not have anything like a complete view into customers’ lives and spending habits, but in their specific area, they know a great deal.

If Sam goes to his local coffee shop every Monday through Friday and orders a double espresso and a croissant, the coffee shop can be proactive with Sam for future orders or know what to offer him as incentives for a certain amount of spend. It's a Saturday and Sam doesn't normally show up to the coffee shop. On Friday, the coffee shop could encourage Sam to show up on Saturday as well by offering him a free croissant with the purchase of his double espresso or on Sam's birthday (information the shop is likely to have if Sam provided the basic information when signing up as a frequent customer), the shop could do something special and custom for Sam, based on his spending habits throughout the year.

OFFLINE TO ONLINE

A few of the most striking trends regarding embedded finance in the offline world are:

- Cards

- Invisible Payments

- Checkout-Free In-Store Shopping

- Buy Now, Pay Later

- Internet of Things

- Insurance

In the pages that follow we will explore these trends more closely and look at relevant examples.

The Ancestor of Embedded Finance Offline: Cards

One of the first instances of embedded finance in a brick-and-mortar context came through payment cards issued by department stores. The “closed-loop cards,” were also known as single-purpose cards because they could only be used in one location, at the department store. With closed-loop cards, merchants do not need a network such as Visa or Mastercard, nor do they need an issuing bank. The merchant acquiring bank is all that is needed, so terms for the merchant are very advantageous, resulting in better margins. The greatest benefit, however, is keeping the customer in the store's network and increasing their customer lifetime value or CLV. An in-store card can offer generous incentives or bonuses because of its advantageous terms. Have you ever been at a department store, maybe a Macy's or Best Buy, and upon checking out, been offered a store-branded card that offers you a significant percentage off the purchase you are about to make and an ongoing discount for all future purchases made at that shop? If it is a store that you frequent often, it might make sense because the discounts add up over time or if you are at a home improvement store like a Lowes or Home Depot and know you are going to make a large purchase to redo your kitchen, as an example, the offer is quite attractive.

Across the world, we still see closed-loop cards in play, though it has evolved somewhat. Starbucks is probably the most pre-eminent example. The Starbucks card/wallet requires customers to load credit onto it, so it is prepaid, while most department stores are willing to offer credit. This way of doing business brings in tremendous revenue for Starbucks, and not just in lower-friction coffee and pastry sales. Starbucks holds about $1.5 billion in customer funds at any one time, and they held as much as $3 billion in December of 2020, as their cards are popular gifts for the holidays.2 As with funds held by banks, this money can be claimed at any time, but meanwhile Starbucks is free to earn interest on it. These Starbucks accounts began as cards, but evolved into mobile wallets. While the world knows Starbucks as a coffee company with stores across the globe, in the years before Apple Pay, Starbucks was far and away the most successful mobile payments company in the world.

Invisible Payments

The most fundamental form of payment is the cash transaction, which still covers 20% of consumer spend in the US, even in a rapidly digitizing world.3 In some countries, such as Japan and Germany, the number is far higher, while in Sweden and Singapore, it is rapidly approaching zero. Cash can typically not be used very easily in the digital economy, but it is possible, and with billions of cash-dependent customers around the world, it is still an essential form of payment. The problem with cash is that it yields the least data to merchants and none at all to issuers. Cash makes it difficult for merchants to form relationships with customers. For the greater privacy advocates, this is a feature, not a bug.

Invisible payments, also known as embedded payments, are the opposite of cash transactions. They are completed without the traditional handover of cash or even swipe of a payment card. They happen because of stored credentials: payment instruments, either cards or bank account information, that are stored with the merchant. They deliver a large amount of data to the merchant, who can use this to forge stronger bonds with customers.

Storing payment information with merchants, particularly involving bank accounts, involves trust, for obvious reasons. Payment information can be stored with an endless number of merchants, which is convenient, and carries many advantages, but not all merchants have the same protections and data security. The security has increased over time with the movement into the cloud with the likes of Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and others, but recall the Target breach of 2013, in which the payment information of more than 40 million cardholders was compromised. This breach involved a flaw in the point-of-sale system provided to Target by a third party, and had nothing to do with storage of data for future use. In other words, storing data with merchants is not necessarily any more dangerous than making a single payment.

Many consumers were first introduced to invisible payments with the rise of Uber, which was founded in 2009 but rose rapidly in popularity in 2012. You may remember how game-changing it felt to use this service for the first time. Uber knew exactly how much to charge, told you this in advance, and the payment happened only when the ride was completed. There was no delay in finishing the ride, no taking time to find your card or cash, and no thinking about which payment method to use. Instead there was complete transparency in the amount you would be charged, right there on your mobile phone screen. To make this magical experience happen, the mobility company required users’ payment card information to be preloaded into the app before use. This has now become common practice in many online services, but is less common in the offline world (but see Starbucks, above).

The appeal of invisible payments is undeniable: it's all about convenience. A buyer doesn't need to dig out her card or, in some cases, even mobile device—the payment simply happens.

If macroeconomic behavior teaches us anything, it is that convenience trumps most competing priorities (price and security are often but not always exceptions) and invisible payments offer today's busy shopper yet another advantage in the race to get through the day and get home faster. For this reason, data and trends show that invisible payments will continue to increase. The technology research firm Juniper Research estimated in Fall 2021 that invisible payments would process $78 billion transactions during the year, compared with about $10 billion in 2017. This represents growth of 700% in just four years.4

Matt Harris, Partner at Bain Capital Ventures, explains:

Perhaps five years ago, the next leg of the journey became obvious. Once financial services were digital, they no longer needed to exist as discrete products; they could become embedded in software that consumers and businesses use all day long, and with which they have a durable and data-rich relationship. We are early in that process, and it requires imagination to see where it ends. For a while, it's just going to feel like everyone we do business with wants to offer us a debit card, make us a loan or help us save 15% on our car insurance.5

Eventually, though, when these products and services are all fully digital and embedded, the cognitive load of opening and managing these accounts will go away, as the operations are executed and automated by the software in which they are integrated.

In-Store Shopping: A Fully Checkout-Free Experience

The introduction of invisible payments in brick-and-mortar stores is a game changer. Invisible payments will continue to grow in importance because they offer advantages not just to consumers but to merchants as well. Invisible payments at the brick-and-mortar store means not just a faster checkout (which today, as in banking, often means self-service) but the possibility of no checkout at all.

Outside of offering a more convenient shopping experience for the customer, what does a checkout-free experience offer the store, i.e. the merchant? Checkout-free stores allow merchants to reduce personnel and free up space used for checkouts, providing more inventory for other items. Because items are tracked from the moment they are picked up, sellers can learn more about customer behavior and where to place items for optimum uptake. This concept of tracking items from the moment they are picked up is not new and one most of us are at least slightly familiar with. How many of us have gotten charges on our hotel bill from the minibar by grabbing that bottled water or box of peanuts for a late-night snack? Checkout-free stores take the minibar concept into the digital age. This additional customer data, tracking both inventory and customers, allows merchants to fine-tune their loyalty and rewards offerings on a highly granular level. Did customers pick up the name brand bag of chips to replace it with the generic brand later? The merchant could use the data to offer coupons or rewards on the name brand items in the future.

Due to the low number of checkout-free stores in existence today, only a small percentage of the population has shopped in one, but all evidence points to the expansion of these stores moving forward. What will your first checkout-free experience be like? Here's a sneak peak for the most curious of our readers.

In March 2021, with the Covid pandemic still in full force, Amazon opened cashierless Amazon Fresh stores in London. Featuring “Just Walk Out” technology, also known as Grab & Go, that allows shoppers to collect their goods and just walk out, Amazon Fresh stores caused something of a sensation, and not just in the UK, Media around the globe paid close attention. In a time when every additional human contact could be dangerous, or even fatal, shopping without the need to pause and scan goods or talk with a cashier seemed to respond to deeply held customer desires.

The idea is simple but the execution requires several interlocking systems of scanners. Upon entering the store, customers scan QR codes on their Amazon apps, which contain embedded payment information. A series of overhead cameras and sensors backed by artificial intelligence track users’ progress through stores, tallying up purchases as they progress through the aisles. If a customer picks up an item, they must put it back in the same spot or they will be charged for the item. As an example, you can't pick up a banana and put it back in the apple section. When shoppers are done, they simply exit the store with their purchases, and the total value of the merchandise is charged to them via their apps. One shopper at an Amazon Fresh Store described the experience as positive and noted his receipt took about 20 minutes to appear after he left the store.

One of the things that makes Amazon Fresh so attractive for consumers is that it solves a primary problem that we are all acutely aware of—lines and dwell time. By allowing people to focus on the primary action or experience, in this case, picking up key grocery items, and having everything else be secondary (including the payment), you will have happier customers who will over a life cycle spend more money with fewer abandoned carts or frustration with scanning items themselves or other issues. The experience becomes more immersive and allows the retailer, Amazon Fresh or others, to focus on creating a more engaging experience while in store or offering a broader range of products.

Because they make checkout easier (or nonexistent) for customers, they reduce cart abandonment online and off, and encourage return visits. One 2018 estimate said removing checkout lines across the industry could bring in $37 billion in increased sales worldwide.6 How many times have you been in a store with a cart full of items to get to the checkout line that is rows deep to decide that maybe tonight is takeout night? Customers waste hundreds of hours a year waiting in lines, and the Covid pandemic and digital shopping behaviors have reduced many shoppers’ capacity for dealing with crowds and waiting long periods of time for items they can receive in other ways.

The idea of no checkout line at all is certainly an alluring one but what happens if someone tries to steal something? There must be a higher chance of theft with a checkout-free experience, right? It turns out that the opposite is true. Checkout-free stores are nearly impossible to steal from. Inventory is minutely tracked, and merchants can pinpoint when an item left the store and with whom, resulting in fewer losses to shrinkage and misplacement.7 Ars Technica reporter, Sam Machkovech wrote an article about his experience with one of the checkoutless stores, Amazon Fresh, and his ability to trick the system by entering the bathroom and changing clothes.8 The result was that Sam was only charged for the items he picked up prior to entering the bathroom, not what he picked up after changing. Of course there will be a minority that will find a way to game the system, but given the level and complexity of tracking in this new world era, the minority that beats the system will be less than the traditional checkout experience.

Author and commentator on digital financial services, Dave Birch believes this process needlessly violates customer privacy, because customers are identified rather than merely authenticated or credentialed. In other words, rather than saying, Ok, here is a shopper with a valid card who has permission to make a purchase, the store will say, “Oh, here's Dave Birch, maybe he'd like to buy some more pecans today.” This is a tricky issue that may depend on customer comfort levels, and is a case of technology outrunning social etiquette.

At the time the Amazon Fresh cashierless experiment launched, experts in both the retail and payments worlds predicted Amazon would soon see competitors in the checkout-less market, either using technology purchased from Amazon, or a homegrown solution.9 Time has proven these estimations correct. In the fall of 2021, Tesco, another major UK grocery chain, launched its GetGo stores, using very similar technology. The artificial intelligence in this case was said to build unique profiles of shoppers without using facial recognition software. Dave Birch would approve.

The insights gained from checkout-free stores mean that, to name just one example, tailored offers can be sent to users’ apps based on the data in their profiles. And more stores are set to join, eliminating the pain point of the grocery checkout line. Around the time of the Tesco announcement, two other grocers, ALDI and Morrisons, also announced plans to go checkout-free.

While checkout-free stores are still in the experimental mode and far from ubiquitous, this is beyond the concept of innovation for the sake of innovation. Merchants employing checkout-free experiences learn more about their customers, offer them relevant deals, and ultimately sell more products.10 With these successful early experiments, it is easy to see these experiences becoming the norm in the next few years. The future is bright for brick-and-mortar customers, and the merchants who serve them.

Buy Now, Pay Later

One of the most striking trends for both online and offline merchants that came to fruition in recent years is Buy Now, Pay Later, often shortened to BNPL. Merchants have struggled for years to get customers inside their own closed payment loop as described above, such as store cards, with few finding notable success. BNPL has enabled merchants to offer a similar function today. When BNPL emerged several years ago, first in Europe with the likes of Klarna and later in the US, many in the fintech space (and some still do) scoffed at the concept, calling it another name for layaway or installment plan purchasing, or just another form of consumer debt. While this may be true in the most basic sense of allowing consumers to purchase things they want today and pay for it over a period of time, the technology and methodology around BNPL have advanced quite drastically. There is no denying that entrepreneurs have built billion-dollar businesses on this model, and that it has found an enthusiastic customer base among credit-averse millennial and Gen Z shoppers. This group watched their parents and older siblings struggle with debt through the financial crisis of 2008–2009 that we have already seen was a major catalyst for the development of fintech.

One of the most important advantages of BNPL is a legacy of fintech innovation—transparency around pricing. We have already spoken of the banking industry's misalignment of incentives with its customer base. Banks are also notorious for hidden fees and fine print that no one in their right mind (other than lawyers and fintech nerds like us) reads.

Everything that can be said of banks is doubly true of credit cards, one of the banking industry's primary revenue drivers. Credit cards’ ease of use and the ease of forgetting to pay off balances, have made credit cards the preferred payment form of millions of Americans and Europeans. In the US, for example, if you pay your balance every month, you benefit from rewards such as cashback and airline miles while paying no interest. But if, like millions of consumers—the vast majority of credit card users in the US—you carry a balance into the next month, you will be hit by high interest rates and quickly come to appreciate the downside of compound interest.

Buy Now, Pay Later looks to be an old offering by a new name, and it does have much in common with those earlier incarnations offered 50 or more years ago, but the payment landscape of retail sales has changed. Merchants are now forced to do business with the large payment networks who charge 2% or more for transactions. That means that for every payment you make for an item, 2% goes to the payment network behind the scenes. For businesses with narrow margins, that is a huge amount, which is why cash is preferred at so many businesses, especially mom and pop shops, even though managing cash carries costs and risks of its own. In major cities in the US, restaurants, nail salons, and corner shops prefer cash and incentivize you to pay that way by offering a lower price if you pay with cash. The expense of accepting cards also helps ensure the continued presence of checks at the point of sale in the US, which astounds visitors from other countries.

Fundamentally, BNPL results in customers spending more than they otherwise might, and to complete sales they might otherwise abandon. It widens consumer choices, and opens up products that might otherwise be out of reach. While some BNPL customers are wealthy, the majority are of limited means. A study from PYMNTS.com showed that 57% of BNPL customers earn less than $50,000 a year.11

BNPL offers merchants three crucial advantages over other forms of payment:

- Merchants, unlike payment networks, have complete visibility into what customers are buying. This is the Level 3 data mentioned above, also known as SKU-level data (SKU stands for stock-keeping unit). Getting access to this is the Holy Grail for loyalty and rewards, but Visa, Mastercard, and the banks do not have it. With this data, merchants can offer special deals on certain items to customers who want them. That level of specificity is rarely possible for others in the payment value chain.

- BNPL forms its own payment network that operates in parallel to other payment rails. Customers can pay by directly linking to their bank, rather than a payment card (i.e. Visa or Mastercard). Alex Rampell of Andreessen Horowitz notes on Twitter that because of this, BNPL may be a gateway to a true payments revolution, and the most serious threat the payment networks have faced since cash. Currently BNPL operates simply, offering installment plans for repayment of borrowed funds. But BNPL payment systems have the potential to extend beyond point-of-service loans to other types of offerings unique to the businesses offering them. While we typically associate BNPL with large purchase items, the principle of the parallel payment rail directly to a bank account could be applied to even the smallest of transactions. As Rampell puts it, “Rather than a financing carrot, it might be a discount carrot, a warranty carrot, etc.”12

- BNPL also allows product manufacturers to have direct relationships with customers. While the internet similarly enabled direct relationships with customers, BNPL extends this to offline purchases as well. Take, for example, a bicycle manufacturer. With merchant cooperation, the manufacturer could learn of a brand enthusiast who has just purchased a new bicycle and extend special discounts, offers, or rewards for complementary products.

BNPL extends the relationship with customers beyond the point of purchase. A credit card customer may be paying off a major purchase years later, but she may have forgotten what the purchase was, and the merchant plays no part in that. BNPL means customers have a reason to come back to the store. Because loans are offered on singular products rather than baskets of goods, the customer retains a strong connection with the product, as opposed to paying off a portion of an amorphous credit card bill each month.

Merchants gladly front the money to customers for the purchase because it converts more customers and overcomes the reluctance of hesitant buyers. Merchants include this cost as part of their CAC or cost-of-acquisition and reallocate part of their marketing budget to cover the costs here. Consumers are happy with the relationship because, as previously discussed, there is a huge convenience for them being able to pay at the point of context. You walk into a store and see the TV you want. You are able to walk out of the store with that TV that day and the rest is background to the primary intention. You don't have to request a loan through a bank which may or may not be approved and in any case, can take a number of days or even weeks to hear back.

BNPL in Practice

What type of impact does BNPL have on merchants? Let's take a look at the high-end pet supplies manufacturer Whisker that charges $500+ for a self-cleaning litter box and unsurprisingly, its financing option has many takers. The company saw conversions increase 16% when it introduced BNPL financing through BNPL partner Affirm.13

As with everything else fintech-related, this industry is cyclical, and banks are taking a piece of the BNPL pie. While banks like JP Morgan Chase, the largest retail bank in the US, joined the BNPL movement, the challenge still remains on the exact use case. Banks typically do not know what a customer has purchased (though they can often make good guesses). Banks may miss some benefits of BNPL, but cutting down on cart abandonment and increasing spend per card may still make the endeavor worthwhile. Chase, with its massive card portfolio, is willing to take the chance.

In the online world, PayPal, which is in a very similar position to banks in terms of limited visibility into customer carts, has been offering BNPL for many years without great fanfare. PayPal has had a front row seat to cart abandonment for several decades now. Increased customer spend and reduced abandonment clearly bring in enough revenue to make extending credit worthwhile. There is an argument to be made that banks that say no to BNPL as they have said no to personal loans will miss out on BNPL's considerable advantages to financial institutions.

You may be wondering, what happens if consumers can't make their payment for that new couch they bought? You aren't alone and it certainly happens. Critics of the BNPL movement often focus on the high percentage of people who are delinquent on their payments. Customers who miss payments on BNPL loans enter the same collections process used by other types of lenders. Credit Karma noted in a 2021 report that 44% of its customers had used a BNPL service, and 34% of those borrowers had missed at least one payment.14 Affirm noted in the same period that non-delinquent loans, meaning loans with no missed payments, made up 95% of its book. But all lenders know the losses from one bad loan can erase the revenue from many good loans. Now, let’s take a look at another company in the space, Katapult.

The Internet of Things

The Internet of Things is the network of connected devices in the world around us. These are everyday objects, not computers or mobile phones. They may be stationary or moving, useful in their own right, or only as a point of internet connection. We will walk through examples of each of these kinds of products. While right now there are a handful of examples that really showcase embedded finance in practice, soon, there will be many more, and they will be so ubiquitous in our lives that we may not even be aware of them.

Our world is full of internet-connected devices that act as a field of sensors detecting the activities of individuals going about their day. In a way it is a marketer's dream, since data is the name of the game for sales and marketing today. What do you know about your prospect? Can you anticipate her wants? Can you prove yourself valuable enough so that she seeks you out?

To some, this activity is by its very nature nefarious because it impinges on privacy (but what is privacy when your mobile phone manufacturer, service provider, and various apps know exactly where you are and even how many steps you took that day?). While privacy concerns are valid, tracking customers is not necessarily sinister. It is an activity of commerce and an opportunity to meet customer needs more efficiently than ever before. As author and commentator on digital financial services Dave Birch noted earlier, sometimes we are asked for more information than is necessary (and sometimes we volunteer more).

Companies in certain industries enjoy privileged insights into the day-to-day movements of people. The transportation space, particularly the automotive space, is an innovation hotspot for the simple reason that we as consumers spend a lot of time moving, whether driving or taking public transportation. On public transit systems across the globe, commuters can use stored payment credentials to access subways, buses, and trams, or to pay for parking. Where once coins had to be dug out of pockets and purses and forced into grimy germ-laden slots, now mobile phones or cards waved near sensors suffice. This doesn't mean the transactions are faster—indeed, it's often the opposite—but it does mean travelers don't need to remember to carry a fistful of coins or bills, standing in long lines to get a metro card and leave with leftover balance, and can avoid touching devices shared by many others throughout the course of a day.

Take the case of driving. The Department of Transportation estimated in 2017 that Americans spent an average of 1.1 hours a day driving, which cumulatively works out to more than 17 days a year behind the wheel.15 (Americans drive about twice as many miles per year compared to Germans, who cover the most distance on the road in Europe.) With 5,000 miles of toll roads in the US, a frequent pain point for drivers is sitting in traffic waiting to toss coins into a plastic receptacle or hand them to a toll collector.

Electronic toll collection (ETC) devices, such as EZPass, used in the Eastern United States, California's FasTrack, France's Liber-t, and Spain and Portugal's VIA-T to name just a few, save their users both time and money. An inexpensive plastic device that is loaded with an individual's payment credentials is placed on the windshield of your vehicle. Every time the vehicle passes a certain point, usually but not always a toll charging a specific sum, payment is deducted from the connected account. The amount charged by ETCs is often discounted from the cash payment rate. This may seem surprising, since cash earns discounts for purchases such as gasoline, but electronic payments have greatly reduced the cost and risk to toll collection companies of storing and transporting physical currency, not to mention staffing toll booths.

Without EZPass, FasTrack, Liber-t, or VIA-T, drivers need to wait in line to hand over cash to an agent. This is a convenience users are willing to pay for, and they do, depositing lump sums of money into EZPass accounts to be used when needed, similar to the cards and apps used by Starbucks and other quick-service coffee restaurants. Customers are willing to load hundreds of dollars at a time because they use the product on a consistent basis or they acquire a pass at a rental car agency to ease the friction of travel even if only for a few days. The Pennsylvania Turnpike Authority said in 2020 that 86% of drivers on its roads used EZPass.16 Many exits on the Pennsylvania Turnpike are only available to EZPass customers, meaning cash customers will need to drive out of their way simply because they are cash users. FasTrack in California is particularly aggressive in removing any alternative payment option—you either use FasTrack or a photo is taken of your license plate and you are sent an invoice for more money (payable by check or card). Some of the European systems are using direct debit to the user-linked account to pay for the toll fee and in the near future it is probable that open banking, in which third parties can access consumers’ funding accounts, will be used to trigger a payment initiation from the user account every time she crosses a Liber-t or VIA-T point of control.

EZPass is also used to measure and optimize traffic flow, as are mobile phones and internet-connected cars. Conduent, the company that operates EZPass, can share this data with municipalities in order to determine where motorists are getting slowed down or stuck. So-called smart cities can use all the data generated by moving residents to eliminate bottlenecks and optimize the flow of people, goods, and services. Some municipalities, of which Singapore is a notable example, have taken this concept quite far and serves as an example for others to follow.

Transit data in cities is enriched by information provided by stored credential payments. Where previously a transit system might know how many people entered the system at Station A and exited at Station B, now it can know who entered at Station A and exited at Station B. Smart cities can utilize data from bike rentals, such as London's Santander Bike and New York City's Citibike, transit systems such as London's TFL (which was also one of the first in the world to implement contactless payment from one's payment card), and toll collection points, to gauge where people need to get to, and when. While this data may not be of much use to New York City, cities such as Singapore and Berlin, with some of the best transit systems in the world, have embraced the use of data in smart city strategies to improve travel for residents and visitors.

The network of data receptors that is the Internet of Things is a precursor to a future where everything is connected and at the consumer's fingertips. Invisible payments have the ability to make life smoother and more efficient. It is notable that payments are rarely shown in science fiction movies and TV shows, because they are, naturally, embedded and invisible.

The Connected Car: Tesla and Beyond

Connected vehicles such as those in Tesla's electric fleet offer numerous opportunities for IoT and embedded finance. Like any device with stored payment credentials, internet-connected cars can make purchases with the driver-user's consent, often using spoken commands.

While some users may doubt the utility of a smart oven or smart refrigerator, few debate that connected vehicles can improve their driving experience. Tesla's vehicles not only warn drivers of traffic jams and optimal routes, but also report on weather hazards such as tornadoes and hurricanes.

Connecting Cars and Payments

We are seeing more and more how IoT is playing a role in embedded finance, but there is another way that traditional industries can have a piece of the pie. Other car manufacturers are getting involved from a different lens, starting with payments. As we know, a car is typically the second largest purchase we have as individuals in our lifetime and car manufacturer Volvo has taken the opportunity to turn that model on its head. Volvo offers an alternative to buying or leasing a car and instead has a subscription car service called “Care By Volvo.” There is no down payment or long-term contracts. Through the subscription service, everything related to your car experience is included—things like auto insurance, maintenance, protection for the tires, wheels, breakdown issues—all are included if you subscribe to the car. Michael Jackson, the former COO of Skype and non-executive director on the board for Volvo sees a strong comparison to the world of communications as he says:

20 years ago, if you wanted to make a phone call, you had to go to the phone on your desk and pick it up and use the phone company AT&T. Now phone calls and communications are built into everything we know. This is true wherever you are, there is a chat function built into websites, there is a click to chat button within your car. You are not using the phone company any longer. This is what embedded finance is all about.

What does that mean for the Volvo driver with a subscription? Michael says: “It means they pay their fee to get their car and it automatically comes out of their bank account. But it also means that whenever extra services are used, whenever you do, it gets automatically managed. Parking is automatically debited, extra software in the car is automatically debited, functionalities debited, etc.” Why does this work? Because the customer doesn't care to be involved in these details and frankly, there is no reason they need to be.

As to the importance of embedded finance for car manufacturers and beyond, Michael says, “Embedded finance is definitely what we're going to see in 20 years time, the same way as we have seen with embedded communication. You need to build payments and other core financial service components naturally into your product. You just need to. It's what people expect.”

Let's move over to an iconic brand in the automobile space, McLaren. Why would McLaren want to get into financial services? For starters, racing is quite an exclusive sport. Stadiums only hold a limited capacity, and merchandising is quite limited to things like hats, shirts, etc. While McLaren has great success with Formula One and racing, they are much more than that. They are also a world class engineering company for new materials, manufacturing techniques, etc. How could a brand like McLaren expand their fanbase? McLaren and others like them are finding other ways to engage and expand fan bases outside of the traditional path through channels like eSports. There are virtual races happening 24 hours a day. Why not offer McLaren skins and reward the McLaren skinned car when they win? That reward could then be converted into local currency and spent by the person collecting the rewards.

As Nigel Verdon, CEO of Railsbank, the primary partner and enabler for McLaren to get into financial services, puts it: “It's about developing the relationship between McLaren and the fans. It is not just engagement. It's about revenue. It's about repeat purchases. You learn about the consumer, learn about their wallet and their spending habits. It's about giving the consumer the experience and then using the experience to benefit the consumer and the business.”

This model has real revenue potential. Let's say that McLaren has 1 million fans and through embedded finance and this multichannel approach, McLaren can make $1/mo from each fan. That is $12 million dollars a year. Now imagine this at an even greater scale. Let's take the most popular football/soccer team in the world, Manchester United. According to research from the global market research agency, Kantar, Manchester United has a global fanbase of 1.1 billion as of 2019, some estimate that number to be 1.5 billion now.17 For simplicity's sake, let's use the 1 billion number. Imagine tapping into this fanbase through embedded finance and making even 25 cents a month? That's revenue of $250 million a year.

Embedded finance is also a consumer data play. Sticking with the McLaren example, if you have data on your fans and can see what they are doing, where they are spending money on their cards and on what they are spending on, you can use that data to offer them incentives that are directly relevant to them in a meaningful way. Moreover, if the fan is back at the same racing track physically or virtually in the eSports stadium, you as a brand have a clearer idea on where to place merchandise or advertising. Best yet, the data just discussed becomes owned by the brand as opposed to third parties.

The Internet of Things at Home

The Internet of Things is also sprouting up around the home, typically, at first, in luxury items such as the Samsung refrigerator and stove. Alexa, the virtual assistant technology distributed by Amazon, which takes the form of a speakerphone at home, has allowed its users to pay for things they were ordering on Amazon vocally for a long time. Alexa is indeed linked to payment details stored on Amazon, enabling a smooth payment experience to order whatever a user wants on Amazon itself. Users can now employ the Alexa app to pay their bills by just asking their speakerphone or mobile device.18 But as with robotics, internet-connected devices can also be made very cheaply and very small. In 2015, Amazon took an early stab at providing fingertip convenience in the home via embedded payment credentials with its Dash buttons. These were simple plastic buttons that cost $5 each and contained adhesives to stick on refrigerators, washing machines, or anywhere else. Users could re-order detergent or toilet paper with the click of a button, a dream for the homeowners of previous generations. The information was stored in the user's Amazon account, to make re-ordering as simple as possible. Why is this example of effortless convenience no longer with us? One issue was that many Dash-using parents found their children were fond of clicking the buttons. Repeatedly. Endless supply of dish detergent, anyone?

While it may not seem like a significant problem for the industry at large, the role of children ordering goods and services using stored payment credentials is indeed one of the stumbling blocks of invisible payments, and has even made its way into popular culture. The 2017 film, Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Long Haul, features two children using their parents’ phone to summon an Uber and take a long and expensive journey, while telling each other, “It's free!”

Dash buttons were widely ridiculed soon after their release, and called dystopian, and were ultimately discontinued. The New Yorker quipped, “The idea of shopping buttons placed just within our reach conjures an uneasy image of our homes as giant Skinner boxes, and of us as rats pressing pleasure levers until we pass out from exhaustion.”19 But more pointedly, a Danish court found that Dash buttons violated consumer protection laws because the action of clicking to order provided no information about costs, which might have changed since the previous order, or include hidden or unexpected fees. Virtual assistants such as Alexa offer greater utility and can serve a similar function—but, unless asked, they offer no more information about the cost of products than Dash buttons.

Dash buttons and the virtual assistant devices prefigure smart homes equipped with arrays of sensors and internet connections to merchants that frictionlessly deliver goods via embedded payments. Coffee makers and washing machines will re-order supplies on their own. It is simple to add on services to existing orders, as with warranties, insurance, or more complex financial products. The home will be the venue for these transactions, as the home has become the venue for so much economic activity in recent years.

Insurance

Much like financial services, insurance at the point of context, whether when driving or renting a car or booking a trip, is extremely relevant for consumers and customers. When a purchase is made and the customer is thinking about the product and the company, the right insurance can be offered and chances of uptake are much higher in that moment in real time as opposed to a paper notice arriving weeks later, out of mind, out of context.

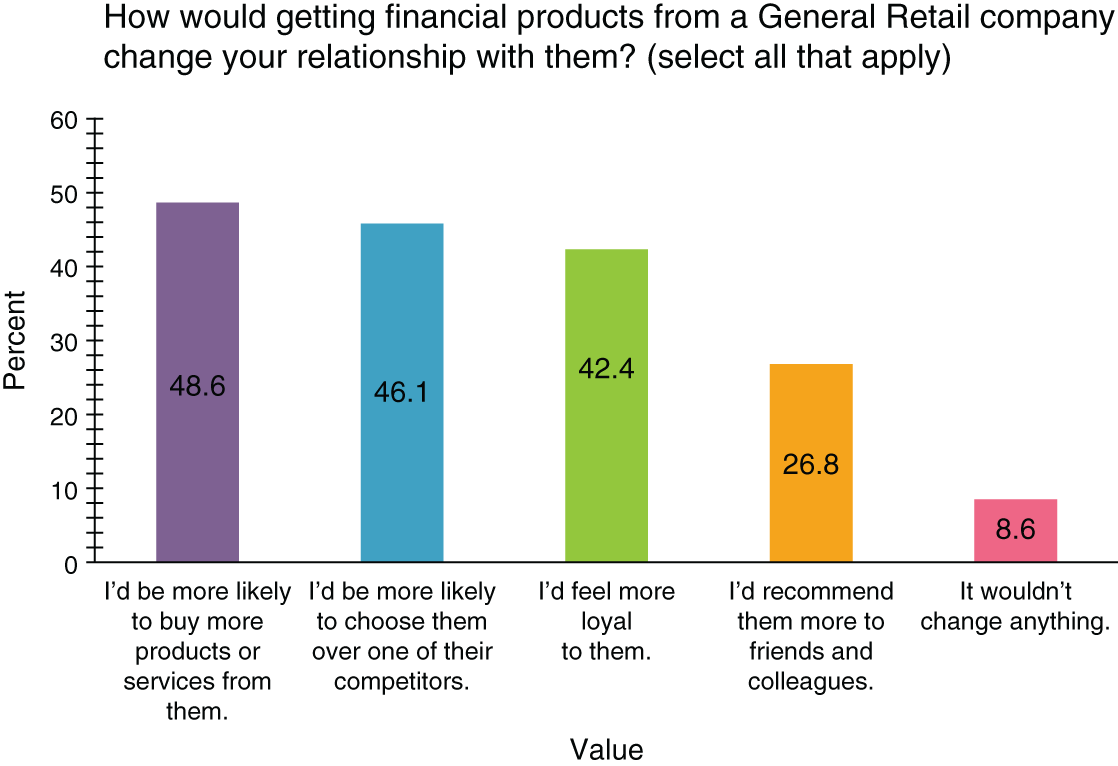

Of McKinsey's estimated $7 trillion market opportunity for embedded finance by 2030, insurance accounts for over 40% of that, at $3 trillion.20 Why? The reason for this lies primarily in that insurance enjoys a huge greenfield. Many younger and underbanked people are underinsured, and technology and data now mean underwriting and the products associated with them can be more efficient and tailored to specific needs. Imagine buying a TV from a brand you love that you have multiple touchpoints with, and the next time you engage, you are offered an insurance product (Figure 4.1). When the service is tied to a product and company you love, you are much more likely to click Yes.

Figure 4.1 Most consumers would think more positively of a retailer that provided them with financial services.

Source: Cornerstone Advisors.

How does embedded insurance play out in the future and who will it impact? Florian Graillot, founding partner at Astorya.vc, notes that even with the advantages of embedded insurance, not every customer will be targeted and benefit. He says:

I believe it's very important to keep that in mind that we are not saying that all the industry will switch online. We are just seeing that customers are in need of digitization at one point. In terms of what penetration to target, it is probably best to look at retailers and e-commerce. As of 2021, let's say 30–50% of the total retail market is now done through e-commerce. These are the type of numbers we can target for insurance and we could even start with a more modest 10–20%.

While this is a rather small percentage, the opportunity is still huge with the insurance market in Europe. As Jennifer Rudden shares in her Statista article: “The gross written premiums of the European life-insurance companies in 2018 amounted to 764 billion euros. In the non-life segment of the market, premiums amounted to approximately 407 billion euros, which constituted just over half of the life premiums value. During 2018, almost 704 billion euros was paid out in life insurance benefits in Europe.”21 We are seeing numbers like this across the globe and the opportunities in this space are vast.

There is the ability to get quite specific and granular with the opportunities within embedded insurance offering specific products for specific use cases. This is particularly true for companies across industries who own the market or have large market share. What areas or products could take off first? It is a safe guess to bet on pocket products, devices or things you always have with you—your watch, your phone, etc. When purchasing devices like this, you are often asked if you want to pay for insurance to cover any damage or excessive wear and tear. This covers many physical goods beyond phones and moves into areas like bicycles. If you purchase a $500 bike, it is normal to be asked if you would like to add insurance on your bike for incidental damages. More and more, customers are accustomed to being asked for such things as part of the checkout process. As Florian puts it, “If you are selling bikes, you are very relevant to sell bike insurance. If you are selling home improvement, you are relevant to sell home insurance. If you are Fitbit or any health wearable, you are relevant to sell either life or health insurance policies.”

Embedded Insurance in Practice

We are seeing an abundance of insurtech startups across the continent of Europe from the UK, to Germany, to France and beyond. Bought by Many, an insurtech startup based in the UK, has already accumulated hundreds of thousands of customers. Get Safe, an insurtech startup in Germany offering insurance products focused on bicycle, home, and electronics, has more than 250,000 customers in Germany alone. In France, insurtech Luko, focused on home insurance, has more than 200,000 customers. While these are still small figures compared to the incumbent insurance providers like AXA or Alliant who have millions of customers, the collective power of these new entrants shows that there is certainly a demand to buy directly from these insurtech startups.

Insurtech startups like Qover, established in 2016 out of Belgium, is a great example of the traction we are seeing with embedded insurance. One of the more exciting partnerships Qover has entered into is with Revolut, the biggest neobank in Europe valued at over $5.5 billion, as of early 2022. As with other products that Revolut and other neobanks offer, there is a seamless customer experience that is easy to access and understand. Companies with large customer bases like Revolut, that has more than 15 million customers, want to embed insurance because they see it as an additional product allowing them to generate margin on their existing customer base. In the case study on the Qover website, the Qover team further outlines why Revolut chose them.22 As they state: “Revolut wanted a partner who was capable of offering innovative insurance solutions across 32 European countries through a single technical integration – an impossible mission for a traditional insurance company.” As Florian Graillot, founding partner at Asorya.vc puts it, “If you are a platform or company with an existing customer base and need to generate additional revenues on your existing base, insurance is a very accurate way to do this. Contrary to the banking space, insurance is the margin product.”

What does the Revolut insurance product look like in detail? According to the use case, “the insurance solution is fully integrated into the banking app allowing users to access the 3 new insurance products in real-time from ‘Plus’, ‘Premium’ and ‘Metal’ accounts.” Revolut customers are able to view details about their insurance policy including all legal documents, in one easy-to-find place. To add to the all-in-one mentality, “the Qover team has put in place technology enabling Revolut customers to report, track and control claims directly in the app. A push notification system allows users to be informed at every stage of the claims process.” This is a prime example of going back to the basic principle of meeting the customer where they are in a way that is convenient to them and enhances their experience.

The US has several new insurance companies that offer quick decisioning as well as mobile and embedded experiences. New York–based Lemonade raised nearly half a billion dollars before going public in the summer of 2020. In its S-1 filing the company writes, “By leveraging technology, data, artificial intelligence, contemporary design, and behavioral economics, we believe we are making insurance more delightful, more affordable, more precise, and more socially impactful. To that end, we have built a vertically-integrated company with wholly-owned insurance carriers in the United States and Europe, and the full technology stack to power them.” Lemonade offers full functionality through the Lemonade API and is embedded in the sites of rental and moving companies. Lemonade also offers home and auto insurance, all done with a few clicks on its mobile app, or embedded in another's app. While its stock had a difficult 2021 as Wall Street fretted about an overheated housing market, Lemonade's market cap is still $2.2 billion, as of early 2022.

There are great examples of embedded insurance already at place from nontraditional brands as well. Ornikar started out as a driving school for young drivers and the company had so much traction they started selling car insurance for their young drivers. This also proved to be successful to the point the company raised a hundred million–plus euros and is now an insurance distributor themselves offering insurance products to all drivers.

Why was Ornikar successful in getting into embedded insurance? They followed the principle of addressing the market need first and then built insurance on top of it. A suggested approach for any companies that have a desire to get into insurance is to follow the guiding principles: Start with addressing the market need, then solving for the customer problem, then focus on building the right technology and product to address that need and the last step is then to plug in the insurance capacity to it.

THE IMPACT OUTSIDE FINANCIAL SERVICES

As the examples above showcase, from traditional retail brick-and-mortar businesses to insurance companies, the opportunities to embed finance into everyday life is enormous. Below are examples of other traditional industries where embedded finance can have an impact: healthcare, media, and telecom.

Healthcare

Healthcare is a sector that has a huge opportunity to move from antiquated ways into the digital world and embedded finance can help it to do so. One such company that exemplifies this is Peachy Pay.

Media

Few industries were as profoundly upended by the internet as the music industry. When music went digital with the likes of Spotify, Apple Music, etc., the role of the record label changed profoundly, but they are still critical for the industry. Just because a business model shifts, it doesn't mean that core components are no longer valuable, they just change shape. Media and music are another great example of an industry ripe with opportunity for embedded finance. In the age of streaming, music creators see far less direct revenue from fans in terms of album or song purchases and fees from live performances, and the time it takes artists to get paid for their work is often long. Instead, the funds go to platforms such as Spotify, which sets the pay scales for creators. As dominant platforms grow in strength, content creators face similar challenges across all creative fields. This has led to the rise of platforms like Patreon, in which consumers of media can directly pay the creators themselves, or Paperchain, in which record companies can provide cash advances to creators based on number of downloads, etc.

Services catering to specific industries can offer targeted products to their customer base. We have mentioned several—Aspiration, Daylight, and more—already in this book. The neobank Nerve is another, built to serve musicians, and including several features built to meet the specific challenges of today's music industry.

Jonathan Larsen, chief innovation officer of Ping An, sums up the impact on embedded finance across traditional businesses best when he says:

What has changed is that digital has upended the distribution models for so many businesses, providing less expensive and more convenient shortcuts. I think that what's really going on here is that what used to define industries, overwhelmingly in many cases for consumers, was the physical distribution channels that inevitably came with the business and the products. You used to go to Tower Records to buy your vinyl and then your CDs, right? You used to go to Blockbuster Video. You used to go wherever you went for your bookshops. It could have been the corner store, it could have been Barnes & Noble, And you used to go to a movie theater to see most of the films that you consume. And we probably still do some version of a number of those things. But clearly, that's the minority, and all of those services have been digitized and they're all able to be consumed through a set of devices that we now all own that are cost-effective and are pretty much ubiquitous and end-running the traditional distribution channels and infrastructure. I think integrated digital providers, and Ping An certainly aspires to be among those, have been able to redefine the industry boundaries by bringing together value propositions in a powerful way.

Telecom

The telecommunications industry is no exception to the challenges faced by other industries. The telecommunications operator Telefonica was one of the first to make a move into financial services in Europe with its O2 banking proposition launch in Germany, supported by Fidor. This banking proposition, powered with fintech Fidor's banking platform and banking license, was offered to all Telefonica's mobile customers based in Germany. This effort by brands like Telefonica to offer banking services to customers was the first attempt at reconciling the experience of lifestyle and banking, ultimately leading to the inception and growth of embedded finance, and its limitless opportunities. Telefonica and other telcos have been looking into leveraging the opportunities provided by financial services to increase customer loyalty and lifetime value, by offering banking services to their massive audiences.

As we will discuss later in this book, telcos played a huge role in bringing banking to underserved populations with no credit history by enabling people to prove their creditworthiness through the payment of their phone bill. M-Pesa is a prime example of a fintech who leveraged this, as we will see.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Embedded finance requires the cooperation of several parties: a bank or regulated entity to create the basic product, a fintech service to act as a conduit, and a consumer-facing retailer to manage the user experience. Additionally, the technology and regulation must be aligned to allow the necessary interactions, and crucially, the end customer must be ready and willing to buy a financial product in a nontraditional context. All of these pieces are in place, and in the next chapter we will look at them one by one, paying special attention to the phenomenon known as Banking-as-a-Service, a necessary underpinning to embedded finance whereby bank offerings can be offered individually in context-specific settings. But the most important point is that, as shown by the myriad of examples in both the offline and online world throughout this chapter, the time is now to begin implementing embedded finance.

NOTES

- 1. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1257230/european-consumers-that-shop-online-and-offline-each-week/ Accessed December 8, 2021.

- 2. https://www.inc.com/justin-bariso/starbucks-devised-a-brilliant-plan-to-borrow-money-from-customers-without-getting-anybody-angry.html Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 3. https://www.frbsf.org/cash/publications/fed-notes/2019/june/2019-findings-from-the-diary-of-consumer-payment-choice/ Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 4. https://www.americanbanker.com/payments/opinion/invisible-payments-bring-visible-benefits-and-risks Accessed October 23, 2021.

- 5. https://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewharris/2021/10/22/a-complete-revolution/?sh=47d7e6d3f3a1 Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 6. http://files.constantcontact.com/30ddbc6b001/713f63a1-9353-4a51-97ad-1e4b0aa3af11.pdf Accessed October 25, 2021.

- 7. https://blog.cfte.education/we-tried-to-break-the-amazon-fresh-system-and-guess-what-happened/ Accessed November 30, 2021.

- 8. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2020/02/amazon-made-a-bigger-camera-spying-store-so-we-tried-to-steal-its-fruit/ Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 9. https://www.digitalcommerce360.com/2019/04/05/amazon-go-may-face-competition-for-checkout-free-stores-in-europe/ Accessed January 16, 2022.

- 10. https://news.crunchbase.com/news/checkout-free-shopping-its-bigger-than-you-think/ Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 11. https://www.pymnts.com/buy-now-pay-later/2021/new-filings-show-missed-payments-are-on-the-rise-at-bnpl-firms/ Accessed January 16, 2022.

- 12. https://twitter.com/arampell/status/1435692958179753985?s=20 Accessed October 25, 2021.

- 13. https://www.affirm.com/business/blog/affirm-whisker-drive-more-sales Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 14. https://www.creditkarma.com/insights/i/buy-now-pay-later-missed-payments Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 15. https://www.volpe.dot.gov/news/how-much-time-do-americans-spend-behind-wheel Accessed November 1, 2021.

- 16. https://www.pennlive.com/news/2020/07/pa-turnpike-raising-tolls-again-in-2021-those-without-e-zpass-will-pay-much-more.html Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 17. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/manchester-united-fans-news-latest-16771943 Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 18. https://voicebot.ai/2020/06/02/alexa-bill-payment-in-india-now-on-android-app/ Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 19. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-horror-of-amazons-new-dash-button Accessed November 1, 2021.

- 20. https://www.simon-torrance.com/blog/EmbeddedFinance1 Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 21. https://www.statista.com/topics/3382/insurance-market-in-europe/#dossierKeyfigures Accessed January 11, 2022.

- 22. https://www.qover.com/blog/embedded-insurance-supporting-revolut-clients-in-their-everyday-lives Accessed January 11, 2022.

- 23. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/20/upshot/medical-debt-americans-medicaid.html Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 24. https://www.hellowalnut.com/ Accessed January 15, 2022.