CHAPTER TWO

THE ORIGINS OF EMBEDDED FINANCE

How big of an opportunity is embedded finance? We will answer this question throughout the book, but before we talk about where we are now and where we are going in the future, we must start with the past.

HOW WE GOT HERE: BANKING IN REVIEW

Let's begin our journey by going back to the beginning of financial technology—fintech. Some industry experts say fintech began in the 1950s when the first credit cards were mailed to 60,000 consumers in Fresno, California. Others point to the widespread adoption of ATMs in the 1970s. Still others look much farther back, all the way to the telegraph system used to transmit financial orders in the nineteenth century.

But the very earliest instance of “financial technology” may be even older than that. Cuneiform is a system of writing developed more than 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, what is now Iraq and Kuwait. It was here, and in a few other areas such as Egypt, India, and China, that agriculture developed to a point where dependable harvests could provide food for urban developments, which served as centers of commerce and other forms of specialized labor. On clay tablets unearthed in the Middle East, archeologists have discovered a system of accounting in cuneiform, including loans and credits to farmers for the purchase of seeds, land, and equipment. It may be said without exaggeration that financial services accompanied the very earliest flowering of civilization.

Note that this is well before coins or cash or fiat money. This was an age of barter, of goods themselves being the means of transaction, rather than abstract symbols of value. The first coins seem to have appeared 3,000 years ago in China and a few hundred years later in Turkey. Both were advanced, literate societies with established social norms and laws protecting persons and property. But the act of borrowing and lending is more fundamental to human activity than the idea of “money,” as any child on the playground can tell you.

Lending appears to have been a family matter in ancient Mesopotamia, with wealthy families lending from their own reserves. In ancient Greece and Rome, banking became more formal and less personal, with lending and money-changing often tied to the economic activities of powerful entities such as temples or government offices.

The institutions we recognize today as banks originated in Italy during the Middle Ages. Banking groups would finance voyages, gambling that ships would return to port with more valuable cargo than they shipped out. In Renaissance Italy, banking became available to more of the population, what we would today call retail or consumer banking. The word bank comes from the Latin bancus, meaning bench or table. Bankers (banchieri) set up tables outdoors, at the entrance to markets, to help customers solve liquidity problems. They changed currency, operated as pawnbrokers, and made loans to people visiting the market. Wall Street brokers began much the same way, trading securities at tables along the tree-lined streets of lower Manhattan, when commerce was still an out-of-doors activity.

The consumer banking most of us are familiar with arrived in Europe and North America in the nineteenth century, along with industrialization and the emergence of the middle class. And of course, the twentieth century saw the trappings of traditional financial life become standardized: the checkbook, the bills arriving like clockwork every month, the plastic cards, and the bankers in their suits and ties.

Financial services companies have always been one of the most avid and enthusiastic adopters of whatever new technology is available. We already mentioned the telegraph. Banks were also early adopters of computers, the first to bring computing power to their employees—after all, banks have a lot to compute. Today the idea of banks being tech-forward may seem antiquated, because banks typically seem to be behind the times when compared with technology companies, but a look at the technology budgets of the largest banks shows that bankers’ enthusiasm for technology remains strong. For example, JP Morgan Chase, the largest retail bank in the US, budgeted an astonishing $12 billion for technology in 2022.1

What has changed is that technology is moving more quickly than banks’ internal processes, and banks must play catch-up. Mobile technology was taken up enthusiastically in the private world, by consumers, before it saw widespread use cases in business (beyond reaching employees at off-hours). This is in contrast to desktop computers, which first saw adoption in business offices before they became known as “home computers.” This gap, along with the stringent regulations banks have followed since the crash of 1929, and later 2008, has created an enormous opportunity for technology companies to enter financial services.

The intersection of banking and technology, or financial technology now commonly known as fintech, began in the internet era. It got its start with digital banking over dial-up internet connections in the 1990s, the arrival of application programming interfaces (APIs) as a communication tool between applications in the 2000s, and truly came into its own in 2009, as the financial crisis wreaked havoc on consumer credit and the entire business of banking. Why was this the moment? The 2009 financial crisis meant that traditional banks became subject to new regulations stemming from repeated crises, and at the same time millions of smartphones (the first iPhone was released in the summer of 2007) found their way into consumers’ hands. This created a unique confluence of circumstances for the new wave of fintech companies to emerge and challenge the banks.

Fintech relies on a number of technology layers from a multitude of providers whose interactions can be quite complex, but consumers don't care how all the processes work together on the backend. Very few users know about the financial systems and programming languages used to deliver services to their touchscreens. An important point about fintech is that, whenever possible, it is automated, and performed with minimal human intervention, removing friction as far as possible to complete any desired action. However, when human intervention is needed, fintechs offer this service, and often more seamlessly than the banks because they focus on providing the best possible customer experience.

Though technological innovation is expensive, it is worth the investment, as paying humans to interact with other humans every step of the way (even to check one's balance in a checking account) is even more expensive and does not provide the benefit of scale. The consumer, using sophisticated technology platforms and tools available nowadays, is serving herself and guiding the actions. This means that she should be able to perform the same transaction at 3 AM that she could at 3 PM, and can do it just as well from home or on a train as at the bank branch. She interacts when it is most convenient for her that naturally intertwines with her everyday lifestyle. As we will see, embedded finance takes this key idea even further.

But to return to 2008, financial services in this era still relied on physical locations to deliver products and services to their customers. Branch tellers and their cordoned-off lines were a familiar sight for millions of consumers every day. But bank branches were expensive to maintain, from rent to cleaning to utilities to supplies to employee salaries, and more. To offset these costs, banks had to make revenue elsewhere, like any other business, or think of a way to reduce those costs drastically. The end result of this necessary cost of doing business negatively impacted the customer. Banks retreated from certain products to focus on others, and fintech entered the breach.

One thing that fintechs collectively aren't focusing on is building storefronts. Since 2008, the US has seen a 12% decline in the number of bank branches.2 In the UK the drop is even more dramatic—a 17% decline since the financial crisis struck in 2008.3 These declines are to be expected as digital banking is adopted. Indeed, bank branches have been in general decline since the 1980s, as card payments have taken transactions away from cash, and telephone and internet banking offered different means to transfer money. As you might infer from these numbers, digital banks have had more success in the UK than in the US. Particularly for small businesses, digital offerings in the US financial services sector still have a long way to go. Its revenue model is not aligning with customer needs, because banks make money when customers make mistakes. When customers don't pay back their loans on time, or spend more than they have in their accounts, the banks profit. When customers are financially healthy, banks can earn money alongside them, instead of against them.

A word here about the basic revenue model for a bank. Banks earn revenue by providing loans, including home loans (mortgages), auto loans, business loans, and personal loans, including credit cards, and from interchange fees received from card payments. For the privilege of borrowing money, consumers and businesses pay interest. Banks also hold customer deposits, and sometimes charge for this service. These deposits provide the capital to make loans.

Customer needs have changed, and the customer base has grown younger and more diverse. New products and services are required to meet the new customers’ needs. Consider how radically other industries have changed over recent decades. It is happening in banking too, but up until now banking has lagged behind the rest of the economy.

CATASTROPHE AS THE MOTHER OF INVENTION

The financial crisis of 2008 resulted from a cascade of causes within the banking industry and in society at large. Loose regulations led to irresponsible lending and borrowing, particularly in the mortgage sector, and then losses from failed loans led to catastrophe for consumers and financial institutions alike. Ivy League graduates formerly flocked to the large investment banks and the secure life they promised, but in 2008 this changed forever. The five largest investment banks at that time were Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Bear Stearns, and Lehman Brothers. All five were severely compromised by toxic assets (mortgages in default) that were worse than worthless—they were negative equity.

Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in September of 2008, the largest bankruptcy filing in American history, and disappeared. Bear Stearns also failed and was bought for a fraction of its previous value by JP Morgan Chase. Merrill Lynch was similarly acquired by Bank of America. A week after Lehman's collapse, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley announced they would become traditional banks offering deposit services to retail customers. American Express also became a bank around this time. This move afforded the banks more protections by bringing them under closer supervision from federal agencies, which was, for a brief period, an attractive prospect. Japan's MUFG Bank subsequently bought a considerable portion of Morgan Stanley, which also borrowed more than $100 billion from the federal government, more than any other financial institution. Goldman Sachs has since seen considerable success innovating on the retail model with its digital bank, Marcus, named for the company's founder, Marcus Goldman, and more recently with its newly launched transaction banking division and TxB platform, which already supports embedded finance use cases.

The financial crisis resulted in a significant tightening of consumer credit, with some banks pulling back entirely from lending to consumers and small businesses outside of established channels such as credit cards. Just because banks no longer wanted to lend didn't mean that the needs of consumers and small businesses changed. They still needed to borrow money, but the traditional providers were no longer available.

THE TECHNOLOGY THAT MAKES IT POSSIBLE

Smartphones, following the birth of the iPhone in 2007, came of age in the wake of the financial crisis, delivering internet access and computing power to consumers wherever and whenever they wanted it. Apple sold nearly 1.5 billion iPhones in the 2010s, according to company sales figures. Here are a few data points to consider. Nearly all adult Americans (97%) own a mobile phone. Most (85%) of adult Americans own a smartphone, and 62% of them have made a purchase on the device.4 The average amount of time a person spends interacting with a smartphone is more than three hours per day.

As of May 2021, China counted more than 911 million smartphone users, and India 440 million. The US was next with 270 million users, out of a population of 329 million. One of the marks of a highly developed economy is the percentage of its population that uses a smartphone. The cutoff is generally 70%, though Japan is a notable exception at only 60%.

Deloitte estimated in 2018 that 59% of the global population had used mobile phones for banking needs.5 This number is likely considerably higher today, especially in response to the pandemic and an acceleration of digital adoption.

As smartphones proliferated in the developed world, feature phones, mobile phones with internet access but lacking the advanced interface of a smartphone, became ubiquitous in the developing world, including the Global South, such as Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa. While smartphones allowed consumers in developed nations to avoid the bank branch for everyday issues and to make purchases, feature phones allowed consumers in countries with underdeveloped financial systems and very few bank branches to access financial services for the first time.

Most consumers, some 70%, in Latin America and Africa are underbanked, meaning they lack access to traditional financial services. The transformation of financial services in countries that had underdeveloped banking infrastructure is far more dramatic than the changes happening in countries with advanced banking systems. Smartphone penetration is also expanding rapidly in the Global South, and with it, so are more sophisticated financial services. Brazil counts 110 million smartphone users, and Indonesia,160 million.

One thing we can say is that using mobile phones for finance can be tremendously empowering. With a few clicks, users can see balances, pay bills, and send money to friends and relatives.

Mobile phones open up a whole world to the curious and seekers of knowledge. The potential is endless, though the reality may sometimes fall short. But on a fundamental level, mobile phones opened up rather than closed off humanity, and connected us with every other mobile user.

While much of the focus has centered around mobile phones, the other component to mobile phone success is mobile internet. Mobile internet access has changed the world forever. Mobile, unlike most previous technology, moved from the consumer sphere to the workplace instead of the other way around. Adoption scaled rapidly, we might even say virally, in the consumer world, forcing companies to adopt policies around bringing these powerful devices into the workplace. When we think about the leading indicators that drive the evolving changes in mobile, they lead back to consumer behavior. This behavior not only drives the consumer but also the business world that interacts with consumers. The consumer has never before been as empowered as they are now, and the way they are consuming cultural products such as books (Kindle), movies (Netflix, Hulu), food (Deliveroo, InstaCart, HelloFresh, JustEatsTakeaway), and music (Spotify, Apple Music) is constantly evolving. This has repercussions across their expectations toward other industries, including financial services, as the lines are now blurred on what specific industry offerings look like as consumers want all experiences to be as simple and easy as the last.

The internet provides communication and information tools to the majority of humans on Earth. It has toppled governments, upended industries, and changed the way people live. No business is insulated from its effects. As hard as it may be to believe today, when the internet was young, many experts downplayed its effects and ridiculed it as a toy or fad. Those predictions are laughable now, but underestimating the internet has happened again and again, always with the same result. Embedded finance represents another evolution along this arc.

Many in the banking industry doubted the internet would have much effect on their business. But, like many other industries, it has fundamentally shifted the way that humans interact with the companies they do business with and with each other. The ubiquity of the internet as a truly global platform is a primary reminder that technology and the ability to connect should not be underestimated. Shoppers now search online for deals first even if they intend on making their purchase at a brick-and-mortar store. How many times have you been at an airport, an appliance store, or an electronic store staring at that item that caught your eye to then go online and see how the price compares to a similar shop?

From the youngest to the oldest in society, this has become the norm. As with anything in life, macroeconomic factors from natural disasters, global health crises, etc. change the way that humans operate in their day-to-day life. When applied to the present, the Covid-19 pandemic, and resulting lockdowns, forced many businesses around the world to shift their business model and interact digitally first with their customers. While this had broad scale implications, it was felt strongest with brick-and-mortar shopping experiences and mom and pop businesses. The pandemic caused them to adapt or die and unfortunately, many of them failed as a result of the inability to connect with their customers digitally. The car rental giant Hertz was among these casualties, as were the retailers JC Penney and J Crew.6 While the pandemic is a deeply timely and personal example for many, it is important to note that there will continue to be large-scale factors that will push consumers online for many of their everyday needs.

Let's now bring this back to the financial services world, one industry that saw both the positive and negative impact of Covid. Those institutions that were already digital first or at least had an adequate digital strategy fared better than those that had digital as a roadmap item that was never quite checked off as complete. Why has this continuously been a theme where banks are slower to adopt change than most, as with the financial crisis of 2008? It goes back to a relatively simple concept: trust. Banks (and other banking institutions such as credit unions, etc.) are the trusted custodians of our financial lives. The financial services industry is conservative with good reason. It is charged with securing the movement and storage of money for both consumers and businesses. It cannot be overemphasized how important a role this is and may be a strong reason why the industry as a whole still uses technology built as long as half a century ago. This has made innovating on time-tested models challenging and expensive. That fact combined with the utter scale that banks had built on the mindset that banks had a monopoly on financial services for consumers. As the world has shifted to external factors, some within the financial industry have tried to get on board by collaborating with startups through acquisitions, investments, innovation labs, and accelerators, but the harsh reality is that large percentages have not. Finding the winning formula can be challenging. In addition to technological challenges, banks are often large organizations with multiple decision-making levels, numerous stakeholders with differing priorities, and departments that often compete for customers. These large ships are difficult to turn, even when the iceberg is clearly visible ahead, but it is possible, as we will see further in the book.

Because of the aforementioned reasons, banks were slow to react to the moment, so when consumers went looking for financial solutions, it was other companies that met their needs.

THE BIRTH OF INSURTECH

According to an article by Jennifer Rudden in Statista,7 insurance is defined as a contract, represented by a policy, in which an individual or a business entity receives financial protection or reimbursement against possible future losses. Insurance is a concept that most, if not all of us, are familiar with in some aspect of our lives. Whether it be for our homes, our cars, our life, or for specific products, it is a class that we all are used to dealing with and it is one that is in great need of disruption. Today, most insurance policies are sold through existing distribution networks, i.e. the brokers. This means that most insurance policies are still sold offline through a brick-and-mortar office. Florian Graillot, founding partner of the Insurtech investment fund Astorya.vc, believes these numbers to be close to 80% for mortgages and 60% for auto insurance in Europe.

The same way that fintech entered the traditional banking space, insurtech, or insurance technology, entered the insurance space. Insurtech has been around since the early 2010s and the initial cohort of companies in the space focused on B2C, or business-to-consumer opportunities. From the early days in the space, discussions were started around the ability for on-demand or just-in-time insurance. These technologies focused on digitizing the incumbents, the traditional insurance companies, by enabling them to distribute insurance products more quickly. The goal was right but, as we have seen across all industries, the movement to digital can take time and there are a lot of bumps on the road. Close to a decade later, there hasn't been much traction to date as companies discovered that the cycles are incredibly long and the technology stacks of the incumbents were outdated, making it very difficult to plug into the systems. These challenges are very similar to those on the banking side as well. Even if a connection is successfully made to an existing system, the work has just begun. As a result, there are only a handful of players that have managed to truly crack the code.

Of course, as with most rules, there is an exception. One such exception is a company known as Wakam. Formally known as La Parisienne Assurances, Wakam is an example of an incumbent that has seen success in digitizing its services. According to its LinkedIn page,8 Wakam “is a digital-first insurance company that creates white-label, tailor-made and embedded insurance solutions for its distributor partners and clients via its high-tech Plug & Play platform.” Wakam has been in the market for a handful of years and now is one of the most advanced in terms of digitization and its ability to plug into external players. In some cases, Wakam is faster at doing this than the insurtechs that are known to compete with them. What makes Wakam different from the other incumbents who have pursued this path with somewhat limited success? Wakam was able to switch all of its technology infrastructure to API-first, which is game-changing and allows them to do a lot more with third parties faster, in a shorter period of time. As Florian Graillot states, “An insurance company, which is running close to 100% of its activity on the state-of-the-art IT system is quite unique, and I believe that this is the reason why there is an ability to gain market share.” As of 2020, according to LinkedIn,9 Wakam was among one of the top 20 P&C insurers in France.

From those early entrants into insurtech, a few companies are successful, but most are struggling. Because of the struggle, there is a real play for embedded insurance, where we can expect to see adjacent players to the early vision start to push insurance products in the customer journey in a natural way, making it easier for the end customer to understand the value proposition. As Graillot puts it:

The core value of embedded insurance is education. When it comes to insurance, for most customers, it's a requirement to have insurance policies for your home, your car, and in many countries, your health. Otherwise, it's not really clear why people should pay for an insurance product. By embedding this kind of product in the same journey they are already engaging with makes it obvious, and the value proposition is really clear, which will result in a higher conversion rate.

As we will share many times throughout this book, the focus on an incredible customer experience is absolutely crucial. This may sound like fluff or something easy to do, but it's quite hard to do well. The same issues that arose in banking with the emergence of neobanks and others applies to the insurance space as well. Graillot discussed the importance of the user experience, saying:

We were running a due diligence on a health insurance startup, and we were having a look at the mobile apps for insurance, and it was quite surprising because almost all of them, both on iOS and Android, were below three stars out of five. It may appear very easy to achieve a great customer experience but the reality is that it's really tough. We increasingly believe that there is something around the product itself, the user experience that insurtech can deliver at scale and better than the insurance company themselves.

FINTECH RISING

As mentioned earlier, one of the important consequences of the 2008 financial crisis was setting up the conditions for fintech to flourish. Technology companies could now offer services previously only available from regulated financial services entities. The growing use of e-commerce, accelerated by the adoption of mobile internet, increased the need for financial services available literally at consumers’ fingertips.

The two areas where new companies first made inroads into banking were payments and lending. PayPal, arguably the first big “fintech” that the world became accustomed to, founded in 1999, was already invading banks’ territory by enabling payments online. While there were many other payments startups that have had an impact post-PayPal, the next big shift happened in the mid-2000s with the several new lending startups. Prosper (founded 2005) and Lending Club (2006) were well positioned to take over unsecured personal loans as nearly every bank pulled back from this endeavor that brought much risk and little profit. Banks held back on lending even as economic activity increased post-recession and the demand for loans grew from both small businesses and consumers. Regulations greatly increased on banks, making lending to these customers more complex and technically challenging. Continued low interest rates also made lending less enticing to banks (and saving less enticing to consumers).

The phenomenon of new companies, soon to be known as fintechs, taking over individual functions previously only performed by banks became known as the unbundling of banks. Banks offer a dizzying array of different products and services. This concept was once a selling point, that an individual or a business could get every product and service related to their financial lives in one place. They were built to be the one-stop shop for your financial needs. Checking and savings accounts, mortgages, credit cards, wealth management and investing—the list goes on, and your local bank can generally do it all. Before fintech, banks competed with other banks on price, and rates, and in some cases geographical convenience, but the products were generally all the same.

The rise of fintech makes sense when you sit back and think about it. How could a single bank with a limited technology budget be expected to create a dozen first-class financial products serving all their customers in a customized way? Add to this that the thousands of community banks in the US lacked—and generally still lack—the technological resources to create top-quality digital products. While they have an abundance of data that should enable them to tailor their offerings, they typically don't have the technology or resources to extract the key pieces of data. Each bank is reinventing the wheel, with thousands of banks each building the same products in parallel and competing with the bank down the street, often while having the same core providers powering them. In general, bank products are generic. You and your neighbor may have very different financial situations, but you are both using the same financial products.

Technology companies operate very differently. These companies are skilled at customizing solutions and offering bespoke options based on the sophisticated use of data about their customers. When this is applied to financial services, the result is an influx of fintech companies specializing in one service that they believe they can do better than anyone else. By offering what they think is a best-in-class product or service, they can own that piece of the pie. This “unbundling” applied to all parts of the ecosystem from international transfers (Wise), investing (Nutmeg), to lending (Funding Circle). To start out with, all of these companies focused on delivering a unique and smooth experience for this single service only.

Partner at Bain Capital Ventures, Matt Harris breaks down the evolution of fintech into two components. The first focus is digitization. As Matt puts it, “If you go back 20 years, that's what the world needed. All financial service companies—banks, insurance, and wealth companies—are extremely analog. This is true from account opening through to servicing, underwriting, everything they did required in-presence work and tons of paper.” The early fintech companies answered this need. Companies like OnDeck, Lending Club, Square, the first neobanks like Moven and Simple. These early fintechs took well-understood and utilized products and digitized them. While this sounds simple, it is actually quite hard to execute well and the companies that did got big rewards. Many of the companies that were created and grew from the first version of fintech Matt described have gone on to become public companies with valuations in the billions or be acquired for hundreds of millions. There was real traction here, but Matt questions how innovative it was: “It really wasn't changing much about those products other than the user experience. It improved the lives and experiences of consumers and businesses but it wasn't actually fundamentally disruptive.”

So what does disruption in financial services look like? That is wave two, according to Matt. In wave two.

Once you digitize these products, you can embed them in software that consumers and businesses are already using all day. By embedding it, you can make them less expensive and you can inform them with the data that these software products contain. Embedding is not an incremental step forward from that analog to digital phase. It's actually transformative, and we've got room to go here.

A prime example of this in action is through fintech companies like AvidXchange or Bill.com. Their account payable software allows companies to save an incredible amount of time by automating the process, which is a vast improvement from using a lock box operator. As AvidXchange shares on its website,10 the goal of the software is to “give teams the flexibility, security, and efficiency to approve invoices and make payments anytime, anywhere.”

The companies that utilize the data and resources around them to truly understand their customers are the best positioned to offer them financial solutions, which is another point in favor of embedded finance.

With the advent of fintech, banks slowly came to understand they were not only competing with other banks, but with tech-forward upstarts. Soon they would realize there were even more competitors in the market than they dreamed of. If we look at the advantages of technology, data, and a deep understanding of your customer, it is reasonable to think that, at least in part, nearly every company in the world has the potential to be a financial services company!

The new fintech companies focused their efforts on one product, or even one aspect of one product, and devoted their skills and expertise in order to execute it perfectly. With regard to lending in particular, bankers have long argued that Silicon Valley technologists lack the expertise to build the right product and manage the risk, but increasingly these functions are automated and software does the work. As financial services become more digital, technology companies feel more at home with these products.

The first question investors ask entrepreneurs is often, “What problem are you solving?” Fintechs were developed to take on specific problems, such as consolidating credit card debt for which banks no longer delivered solutions. For the generation that came of age in the wake of the financial crisis, there was a feeling that banks were simple utilities rather than companies looking to delight their customers and deliver elegant solutions. And we will see later in the book on why this utility angle, called “banking-as-a-service,” is an opportunity banks cannot miss, given the opportunity it represents for them in the era of embedded finance.

Banks foreclosing on the homes of buyers who were encouraged to take out a loan they couldn't afford reinforced this perception. Fintech companies capitalized on this in the early days, emphasizing that banks make money when customers suffer, when they can't pay off their credit card balance every month, or when they overdraft their account. Customers wondered with some justification if their bank was even on their side. This misalignment of interest between banks and their customers led to further alienation and made consumers more likely to seek out nonbank solutions.

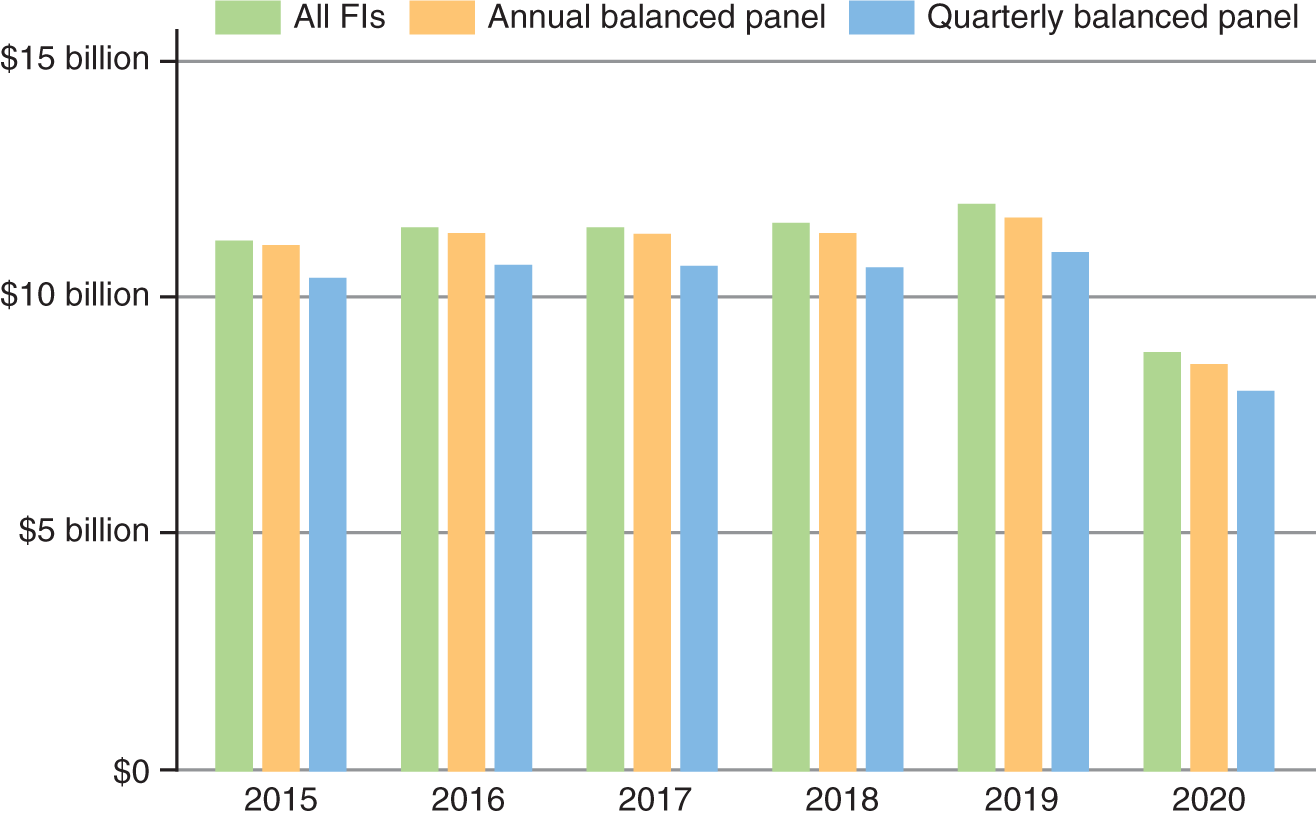

This misalignment is not just theory. In 2020, US banks in aggregate collected about $8.8 billion in overdraft fees. This is an unusually low figure from a very unusual year (Figure 2.1). The previous year, banks collected over $12 billion. JP Morgan Chase and Bank of America collect the most in absolute dollars, but overdraft contributes a smaller percentage of their bottom line than regional and midsize institutions.

Figure 2.1 Aggregate overdraft/NSF (non-sufficient funds) fee revenues by year in the call reports.

Source: CFPB report Dec. 2021 / Consumer Financial Protection Bureau / Public domain

THE ENTRANCE OF THE NEOBANKS

The unbundling of the bank continued throughout the 2010s, with virtually every banking function being reproduced and in most cases improved upon by fintech startups. Even backend functions that are remote from the customer experience were re-created by fintech startups.

This continued innovation led to the creation of a new category of fintech called neobanks—digital-only banks built from the ground up. Neobanks aimed to take over the customer experience entirely from banks, and offered a broad suite of products for their users, though this range of products was generally narrower than that offered by banks.

The first neobanks launched in the early days of fintech: Simple, co-founded by Shamir Karkal and Josh Reich, and Moven, founded by Brett King, are two well-known retail examples on the US side. Both saw great initial traction, and Simple was known for having the second highest NPS (net promoter score) across all of financial services behind USAA, which serves members of the armed forces and their families.11

SIMPLE

Shamir Karkal remembers the early days when the idea for Simple emerged:

I was chatting with Josh who was (and still is) a good friend. And he sent me this email saying, “Let's start a retail bank.” I remember this was 2009, and we spent a lot of time chatting about the financial crisis and everything that had happened from ’07 to ’09. It wasn't completely out of the blue for him to talk about entrepreneurial ideas with me, but, starting a retail bank was like, what was out there? He laid out this vision of how customers hated existing banks. The whole financial model of banks was built around trying to sell more products to customers and charge them more fees. What customers wanted had not been articulated, but what customers wanted was financial wellness, and they wanted to have access to their money, and really to live a better life. There was such a deep disconnect between what banks were selling and what customers were asking for. And Josh's idea was, “Hey, let's just build a simple, easy-to-use customer-friendly bank that held your money, helped you pay your bills, gave you loans when you needed them, and then got out of your way and let you live your life.” And it was just such a compelling idea. I read that email and I was, like, “Oh man, we should do this now.” Facebook and Twitter were already beginning to take off. And yet most banks did not even have a mobile app at that point.

Josh and Shamir launched a website saying, “Hey, we're going to build a better bank. If you like the idea, drop your email and we'll add you to the waiting list.” 200,000 people signed up before the company launched a product.

Simple offered a number of innovative features, including displaying a “safe to spend” amount, to help customers stay on budget, and also put a great deal of thought into the customer experience, including customer service, and both Shamir and Josh logged many hours and late nights helping their early customers solve problems. Simple was ultimately sold to the global bank BBVA.

MOVEN

In 2009, Brett King was a consultant and newly minted author of a book about the future of banking called Bank 2.0:

I was on the book tour talking about banking and how it would evolve with technology. I was talking about the fact you'd be able to download your bank account in the future. It'll be embedded in your phone, you'll pay with your phone. It'll give you advice and coach you on money. This is the vision I was talking about associated with my book. And I was speaking to a bunch of VCs from California and they said, “You know, banks aren't going to do this. So who's going to do it?” And I said, “I will.” And literally that afternoon, I went home and registered the domain movenbank.com, which became Movenbank, which then would drop the bank and it became Moven. That was August the 18th, 2010. Now, at the time, there was no such word as neobank or challenger bank. Josh and Shamir at Simple and myself, we would often talk on the phone and collaborate because there was just no one else doing this stuff back in the day. And so we called ourselves nonbank banks at that time. And then the term neobank, I think Dave Birch (author and commentator on digital financial services) came up with that one.

King continued:

We were the first mobile direct bank in the world. We were at least the first to offer a debit card from an in-app application for a bank account for Moven. We launched that capability in 2012. We had a bunch of other firsts we did. We were the first mobile banking app that used the home page differently than just listing your accounts. We put our spending meter and money path on the app, the financial wellness focus. We were the first to do contactless. This was pre-Apple Wallet and Google Pay, so we stuck a contactless sticker on the back of your phone that was RFID-based initially, then there was an NFC tag. We were the first to do a real-time receipt with categorization for your expenses, which we had by 2013. So we really did pioneer the space. But the problem is that we were too early. In 2013, we had a quarter of a million customers in the United States.

King believes that, despite its traction, Moven was too early, but that its features were influential on neobanks that followed, as well as on traditional banks, and remain selling points for Moven's current iteration as a banking-as-a-service tool.

The gap in the market simply was that the bank account would evolve to be contactless, cloud-based, and would coach you on your money. The biggest selling point we used to talk about were things like, you go to a store and you swipe your plastic card, and you don't know what your balance is. You don't know whether the transaction was good or not. The only thing you know is whether the transaction was approved or not. There's not a lot of context in terms of day-to-day spending that will help you make decisions. So now that's how we position Moven and initially the idea was that it would give you smart feedback. If you're getting out of a taxi and you get a receipt on your phone that says, “Hey, you spent $200 on Uber this month” or you come out of Starbucks and it says, “Hey, you spent $400 on dining out and coffee this month” and that elicits behavioral change because most people just simply aren't aware that they spend that sort of money on those activities. So raising the awareness level was a tool to change behavior and make people financially healthier. And that's the way Moven has always worked.

Why did these early neobanks gain traction? They focused on the technology, making it extremely simple to use, and then doubled down on the customer experience. The concept of neobanks wasn't only gaining traction in the US though. Across the pond, neobanks like Fidor, Monzo, Starling and N26 are prominent European examples as well.

Chief research officer at Cornerstone Advisors, Ron Shevlin, known for his contrarian opinions on many subjects, argues that neobanks did not actually gain significant traction compared with bank competitors. Shevlin said:

I would argue they didn't gain traction, but the gap that they perceived, one perception was right and one was wrong. The wrong perception they had was that consumers didn't want to do business face-to-face, person-to-person. The gap that they were correct in was that there's a way to reduce the cost of the delivery of financial services by not going through the branches.

In other words, digital works, but not because customers don't want to see other humans. Where neobanks succeed, according to Shevlin, is in serving specific niches, such as Aspiration, which serves environmentally conscious customers, or Panacea, which serves physicians starting out in the field.

The neobanks were being formed after years of studying the industry, using contemporary technology and in some cases, operating with updated business models. But neobanks are not necessarily vertically integrated companies that own every piece of the technology stack. They often rely on partnerships with other technology companies that specialize in particular products, and often have banks at the bottom of the stack. Using bank licenses has been an important early step in both Europe and the US. Some of these companies have ultimately gone on to acquire their own banking licenses.

Despite initial traction and a lot of venture funding into the early neobanks, few have gained the traction significant enough to seriously challenge banks, let alone the megabanks with millions of users. The landscape has shifted a bit in recent years and today, neobanks such as Chime (US, valued at $35 billion), NuBank (Brazil, valued at $41.5 billion at the time of their NYSE IPO), Revolut (World, valued at $33 billion), and Tinkoff (Russia, valued at $22.5 billion) are gaining serious traction and, in general, the industry defines them as successful. Each neobank listed above uses varying models to arrive at relatively full feature sets for their customers.

What did those successful neobanks do differently? When asked about NuBank, Chris Skinner, author, commentator and founder of The Finanser blog, believes they have been particularly successful because they reached out for financial inclusion while many banks in the region still do not understand what it means. Financial inclusion in its most simple form is offering banking services to people who cannot afford it. Some 20% of NuBank's customers are individuals who couldn't access banks before. Many neobanks currently try to compete with traditional banks in a similar way. In today's world, the customer needs digital connectivity. Bunq, Starling, and Tinkoff are a few examples of neobanks who understand this concept and are successful in creating digital connectivity to customers who have not been served before.

While, in general, the neobanks have started with one specific product offering, some have done well in expanding their product suites in a compelling way which in turn increases touchpoints with their customers, customer lifetime value, and the total addressable market. This larger movement has become known as the rebundling of the bank and now is being referred to as Super Apps.

What is the difference between the rebundled bank that is digital first versus the traditional players? Customer segmentation. Many neobanks started their journey by catering to specific segments of the population, such as millennials or travelers. Even more specialization is popping up around the globe supporting the theory of specialization and deep knowledge of core customers as a potential winning strategy.

With neobanks’ digital-first (or digital-only) offerings, banking services can be delivered à la carte and on-demand, and can happen in any context. Companies, such as Monese for migrants and Daylight for LGBTQ+ consumers, are addressing specific problems for their communities, and building products that make sense.

At the same time, other neobanks who started off with a specialization are now expanding from their initial highly targeted customer base to a much broader one to achieve scale and hit growth targets. Revolut, who initially targeted mostly travelers, broadened their financial services offering beyond multi-currency accounts and cheap FX toward investments, crypto, and savings, and even launched a SME offering, to maintain its growth rate and increase its total addressable market. Tinkoff similarly started off by offering simple credit products before becoming a Super App touching most segments of the Russian population, and plans to expand to the Philippines.

BEHAVIORAL SHIFTS ACROSS GENERATIONS

Embedded finance is an improvement upon fintech, because companies who are already successfully employing embedded finance already start with a significant customer base. Throughout its history, despite all the headlines and money pouring into the space, fintech has struggled with customer acquisition, which represents one of every fintech company's greatest costs. Part of this has to do with low virality of fintech apps compared to social and other types of apps. How many times a day do you scroll your social feeds, whether it be Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, or Snapchat? What about your banking app? When you do open your banking app, how long are you engaged for? You might tell a friend about a new social network because you want them to join and having them on the platform with you enhances your experience. But, you don't tell your friend about a hot new lending app that will help consolidate your credit card debt, because talking about debt or even wealth can be awkward and uncomfortable and there typically isn't an opportunity for you and your friend to connect and collaborate on the app.

The exception is with peer-to-peer apps, in which you need the person on the other end of the transaction to be part of your network. Another exception is investing and cryptocurrency services, in which people enjoy sharing expertise, and information can be shared without sharing dollar amounts.

There are signs that Gen Z consumers will show greater openness about money and have a greater comfort level sharing personal details, but it is still early in their financial lives. This is certainly true of platforms like TikTok with the craze of “FinTok” and “Finfluencers” including Queenie Tan who, as of January 2022, has nearly 120,000 followers, and Andres Garza, also known as @capital_inteligente, as of January 2022, who has nearly 1,000,000 followers. They openly talk about once taboo topics and make the concepts of financial literacy cool and relatable.

We saw this movement of open sharing for younger generations with the peer-to-peer payments app Venmo, owned by PayPal. Venmo was an early experimenter in making its interactions shareable, encouraging users to invite their friends from other social platforms and making payments fun by adding emojis as descriptions for transactions. It has since made privacy more of a default, but part of the app's original value proposition was showing friends where and how you were spending your money. P2P companies like Venmo are still growing. To quantify the scale of a company like Venmo, Venmo did 2.6 billion transactions worth $159 billion in 2020, 56% higher than the previous year.12

We can't discuss customer segmentation excellence and the success that neobanks have had without mentioning that a portion of the traditional finance service players, particularly credit unions, pioneered the customer segmentation piece for financial services.

Many of the innovations commonly attributed to neobanks using advanced technology to segment customers first appeared with credit unions or building societies. Credit unions serve specific groups, for example, the employees of the same business or industry, and therefore were advanced in tailoring their services to meet the needs of their customers, known as members. There are credit unions targeted toward the military, teachers, Disney employees, and the list goes on.

While there are a few primary examples of credit unions leading from a data perspective, such as the early payment of paychecks based on the simple data of direct deposit information, a benefit for consumers that is still a marquee function of neobanks today, there are some differences for this generation of neobanks. The key difference lies in the neobanks’ ability to utilize technology and data as a primary competitive advantage. Equipped with this information, the next generation of neobanks allows people of different communities, regardless of location, to become part of the movement.

This customization based on data and truly knowing your customer is where embedded finance comes front and center.

LOOKING ACROSS BORDERS: THE CASE OF CHINA

Yassine Regragui, fintech specialist and expert on China, explains that China's development in fintech is very unique, as it started in 2003, 19 years ago, with Alipay that was an escrow service created to build trust between the buyers and sellers of the e-commerce platform Taobao. Over the years, Alipay became a Super App that is today used by nearly everyone in China. Alipay and its competitor, WeChat Pay, now represent over 90% of mobile payments in China, while their offering extends far beyond financial services into lifestyle. The lifestyle services offered by those payment apps are now used more than 50% of the time by users engaging within the Super App. While this is something very typical to China, we are now seeing similar use cases in Southeast Asia, in Europe, in the US, and in other countries, because these payment apps are expanding their services and taking part in the daily lives of their users. The natural integration of financial services in these Super Apps, along with the fact that Chinese consumers are accustomed to going to one place to meet most of their needs, positions China to be at the forefront of fintech innovation. This is in large part thanks to the Big Tech platforms leading the charge when it comes to financial innovation, a progressive regulator encouraging competition, and the banks that offered API-based services early on to enable Big Tech to connect to it.

China's speed of innovation and technological developments can be attributed to several factors. The first factor is that those who started these payment services are nonbanking companies, including Alibaba, an e-commerce platform and Tencent, a gaming or messaging platform, who built a relationship with their users. Many gamers in the US will be familiar with Tencent for their hit games including Fortnite and PubG. This relationship and Chinese cultural tendency of being more open to new services enable the fast and consistent adoption of the new services they deploy. The second factor focuses on the ecosystem. These two giants have many external services connected to their internal ecosystem (the Super Apps) which creates a halo effect and builds trust externally through their partner's brands. The last factor is the Chinese regulators’ openness and support to encourage more competitors to enter to stimulate innovation. By contrast, Western payment companies are kept out of the Chinese market, protecting the homegrown players.

EMBEDDED FINANCE IS HERE

It has taken time for the embedded finance ecosystem to develop. First, banks needed to digitize their offerings and open products and services via APIs, which allow two sites or apps to communicate and exchange data. Next, a sophisticated fintech sector needed to emerge and begin interfacing with bank technology in order to deliver superior versions to their customers, consumer, or business. Third, regulators needed to soften their approach to nonbank vendors offering financial services. Fourth, companies needed to understand the opportunity embedded finance offers and find the right opportunities to offer products. Software-as-a-service companies are seeing the value in financial offerings, which can become the most lucrative parts of their business. Big Tech has the audience, the agility to innovate, and is already searching for solutions to improve customer stickiness and brand loyalty and diversify their revenue base. They also have the data on their users that they can leverage to provide the best possible financial services, at the best price, with the least risk. Finally, most individuals have reached the point of psychological safety needed to start accepting financial services products in other shopping contexts and through different distribution channels.

Embedded finance is officially here. Are you ready?

NOTES

- 1. https://www.ft.com/content/e543adf0-8c62-4a2c-b2d9-01fdb2f595cc Accessed January 15, 2022.

- 2. https://www.statista.com/statistics/193041/number-of-fdic-insured-us-commercial-bank-branches/ Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 3. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8570/CBP-8570.pdf Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 4. https://www.statista.com/statistics/201183/forecast-of-smartphone-penetration-in-the-us/ Accessed January 2, 2022.

- 5. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/financial-services/online-banking-usage-in-mobile-centric-world.html Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 6. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hanktucker/2020/05/03/coronavirus-bankruptcy-tracker-these-major-companies-are-failing-amid-the-shutdown/?sh=119921dc3425 Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 7. https://www.statista.com/topics/3382/insurance-market-in-europe/#dossierKeyfigures Accessed January 11, 2022.

- 8. https://www.linkedin.com/company/wearewakam/about/ Accessed January 13/2022.

- 9. https://www.linkedin.com/company/wearewakam/about/ Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 10. https://www.avidxchange.com/ Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 11. https://www.bain.com/contentassets/7c3b1535c4444f7b8a078c577078a705/bain_report-in_search_of_customers_who_love_their_bank-2018.pdf Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 12. https://balancingeverything.com/venmo-statistics/ Accessed December 2, 2021.