6

Hello, stock market millionaire

Everyone would like to be a millionaire, but what does that really mean? When you look deeper into it, you realise everyone wants the freedom of a millionaire. Not everyone wants a big house or a private jet; not everyone needs 10 bathrooms in their homes or fancy clothes. When people say they want to be millionaires, what they really mean is they want to have the freedom to do what they want, and that often involves time.

So how do you get more time? To have more freedom of time you need more money, but to get more money you need more time. This is where investing comes in.

How the stock market can make you money

Let's forget about the millions for a moment and get started with a basic question: how do you make money through the stock market?

There are two ways to make money in the stock market — capital gains and dividends.

Capital gains

Capital gains are simple to understand. If you bought a home for $500 000 and it sold for $600 000, you made a capital gain of $100 000.

It's the same story with the stock market: if you buy an Apple share for $150 and sold it at $160, you've made $10 in capital gains.

You may be thinking: ‘$10 isn't really helping me on my way to retiring a millionaire though, is it?'

And you'd be correct. Usually it takes a few years, with that beautiful thing called compound interest, before you start to see some really big capital gains in your investing portfolio. For example, if you invested $1000 in Apple at its IPO in 1982 and cashed in now, you'd have a 203 000 per cent return on your money. Or even more recently, if you had spent $1000 in 2001 on Apple stocks, you would have turned that into $500 000 in 20 years.

Until you sell those stocks, though, the capital gains aren't money in your pocket. This is called unrealised gains. It's basically like having a $500 000 home that's worth $600 000 now. You don't see that $100 000 in cash in your account until you sell it. Investors often wonder about the best time to sell shares. Investors in training understand that, as a long‐term investor, you don't sell shares as soon as they bring up capital gains; you hold on to them until you have reached your investing goal. For most of us, that goal is saving up for an earlier retirement, buying a home or putting money away for our children/family. It's not about making a quick buck in the market; it's about playing the long game.

Capital gains are what younger investors usually go for due to having more time on their side, making capital gains more likely. But other investors who want cash flow, aka a lump sum hitting their bank account four times a year, invest for dividends.

Dividends

Dividends are the other way you make money in the stock market, and they're a true form of passive income. It's basically how a company says thank you for holding their stocks in your portfolio; they pay you a small per cent of their profits, usually every quarter. The company's board of directors decides how much dividend to give, and they try and keep it consistent every time. And you still get dividends of companies if you hold them inside a mutual fund.

With dividends, there are three factors to consider, which I like to call the ABCs of dividends: Aristocrats, Burners and Calculations.

Aristocrats

Some companies hold themselves up to a high standard, and promise to provide dividends regularly. Aristocrats are dividend stocks that have consistently paid dividends every year to their investors for 25 years straight and include companies such as Coca‐Cola and AT&T.

Burners

Companies that give dividends don't actually owe it to you — it's just a nice little bonus. So sometimes, if they burn through their money that year, they have nothing to offer their shareholders. In 2020, during the COVID pandemic, companies such as Estée Lauder and Ford Motors paused their usual dividends. The thing is, dividends come from the profit a company makes, so if profits are low or nonexistent, they may choose to not pay out to their shareholders — and there's nothing you can do about it. You have to be careful of burners; if you're trying to pay your mortgage with dividends, this can be a pain.

Calculations

It's important to not get sucked into the lure of some high‐yield dividend offers and look at what is really being offered. Sometimes companies provide very high yields, which is the percentage you get in dividends for each share you have invested.

For example, if you owned $100 of stock A, and the dividend yield was 20 per cent, you'd get back $20 as a dividend. If you had $100 of Stock B, and the yield was 5 per cent, you'd get $5 as a dividend.

Stock A seems more attractive, if you just look at the dividend yield, but it may not be the best option. Let me tell you a little industry secret: those who speak the loudest have the most to hide.

A company that provides a wildly high dividend (‘wildly high’ is really anything that's above 6 per cent), is usually trying to lure investors into buying their shares because the company may be in trouble. An investor in training knows that if they're trying to invest for dividends, they are better off with stocks that give lower dividends but are more reliable than investing in companies that promise high dividends but go bankrupt in a few days.

It's also important to note not all companies give dividends; some companies may look at dividends as getting in the way of their growth. For example, imagine you are the CEO of a fast‐growing electric car company. The company makes $1 billion in net income. Nice. You could distribute this to all your shareholders, or you could use this money to invest back into your company, investing in research, more engineers and bigger factories or machinery that can produce your cars faster. This in turn will make the company grow faster and increase the capital gains of its stock.

See, with dividends and capital gains, companies usually prefer to give you one or the other; they don't like to give you both. A company that needs to grow to give you that capital gain needs the money. A company like a bank or utility provider that gives you dividends is not interested in putting money into development, and they instead share their profits with you.

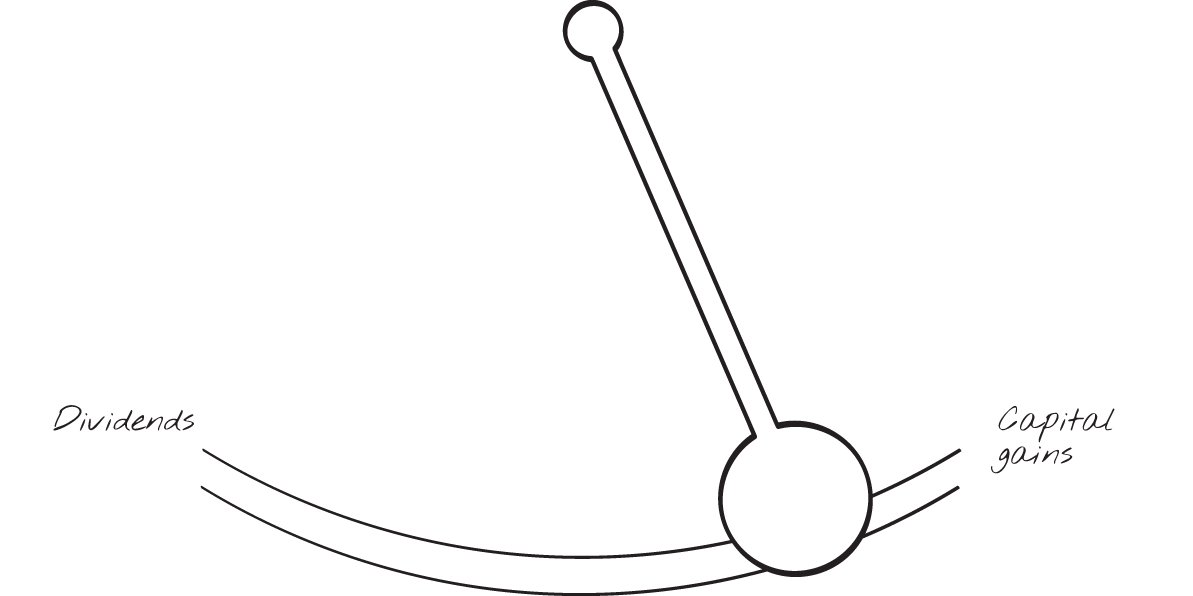

It's like a pendulum (see figure 6.1): when you invest in companies or funds, there is usually a dividend versus capital gain tradeoff.

Figure 6.1: dividends or capital gains

Blended funds (the forgotten Jonas brother of the stock market)

There is a third (not so well‐known) way to make money in the stock market. It reminds me of the extra Jonas brother: there, but kind of forgotten about (sorry, Frankie). These are called blended funds, and they exist to fix this pendulum problem, aiming to get a healthy mixture of both capital gains and dividends.

Blended funds are picked to have a mixture of some growth companies that provide dividends, but also some companies that reinvest their dividends so they can continue to grow and create capital gains (and potentially even larger dividends later on). They're not as popular, but they serve as a good option for people still on the fence.

Starting a FIRE with our wealth

An extreme form of investing is starting to gain traction around the world. It's called financial independence, retire early (or FIRE), a concept coined in the 1992 bestseller Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin and revitalised by Peter Adeney with his Mr. Money Mustache blog in the early 2000s. It's enabling people to retire earlier, in their thirties and forties rather than at the traditional age of 65.

The FIRE movement is built off the idea that you can build up an investing portfolio large enough that it acts like an unlimited little pot of gold. It's like being a trust fund baby, but rather than being gifted a trust fund by your Upper East Side parents, you created it yourself.

You do this by increasing your income (e.g. upskilling in a job), living frugally and investing the difference (as much as you can) into a broad market index fund. People who follow the FIRE movement try to save as much as 60 to 70 per cent of their income. The more you can save, the better.

Sounds too good to be true? I thought so as well, but the maths check out. The FIRE movement proposes that if you get your investing portfolio to the point where you can live off 4 per cent of its annual return you can retire from your job and work because you want to, not because you have to.

But won't 4 per cent every year drain your investment portfolio? This is where your financial knowledge comes in. Remember how I've said the stock market usually returns 7 to 10 per cent annually? Let's keep it at 7 per cent to be conservative. If, on average, the market rises at least 7 per cent annually, your draw down of only 4 per cent will still allow your portfolio at least 3 per cent to continue to grow. It's neat.

The first step is to decide how much you can live off. There are different levels of FIRE:

- fat FIRE is when the 4 per cent drawdown from your portfolio is at least $100 000 a year

- lean FIRE is when that drawdown is $25 000 to $35 000 a year

- barista FIRE is when the 4 per cent drawdown covers your basic expenses (such as mortgage and utilities) and you work part time to pay for any luxury you want to add to your life.

I know $35 000 a year to live off doesn't sound like a lot, but if you think about it, if you were a single person who spent $500 a week on rent, $100 a week on food and $30 a week on utilities (heating, water, etc.) then your necessities are $32 760 a year. This means you'd no longer have to work to survive, and any job you take on is for your own benefit.

There's one catch (because there always is). To live off $35 000 a year by drawing down 4 per cent of a portfolio, that portfolio ‘nest egg’ that you save up will need to be at least $875 000.

To live a leaner FIRE lifestyle, living off $20 000 a year by drawing down 4 per cent, you'd need at least $500 000 invested.

To live a life of fat FIRE, where you have an annual salary of $100 000 a year, the nest egg gets much larger: at least $2.5 million.

I get it, $2.5 million sounds impossible. FIRE requires a level of privilege; you need to not only find a way to increase your income, but you also need to be able to decrease your living expenses. This gets significantly harder when you're a guardian or financially funding your parents' retirement, as many people of colour do, or if you have commitments to your family, such as contributing to a younger sibling's college fund. It also fails to take into account that not everyone has the ability to upskill, such as people living with disabilities, or those who are time poor due to family commitments.

With all that in mind, retiring even 5 or 10 years earlier, at 50 or 60, is still a feat, and something worth aiming towards if you can.

Even investing $500 a month, or $125 a week, for 37 years at a rate of 7 per cent annual returns can give you $1 000 000 (not adjusted for inflation). And if you are a student who may not be making much, you have time on your side, investing $62.50 a week for 46 years also brings you to $1 000 000.

***

Making money through the stock market can be broken into two main options: capital gains, which are suited for those interested in staying in the market for a long time, and dividends, for those who want to earn cash flow. Can't decide between the two? No worries, there's a flavour for that too: blended funds! At the end of the day, making money in the stock market is why you're here — so it's important to understand the different ways investors have been using it in their journey to financial freedom.