5

What's your type (of investment)?

Let's get into what it's like using the stock market to grow wealth.

A good place to start is to understand what investing is. In its simplest form, investing is the process of putting your money into something with an expectation that it will make a return. The word ‘expectation’ is important; it's not guaranteed that you'll make a return on your money, even though that's the only point of investing. You could put that money into real estate, a stock or even into a Birkin bag collection; all of these are forms of investing, because money is being allocated with the goal of not only getting your money back but making a return as well.

That's it.

Investing is just the idea that you throw some money into something, and you hope more money comes out.

No men in suits in sight.

There are many different ways to invest your money, but I'm going to break down the most popular ones you'll come across:

- stocks/shares

- bonds

- mutual funds

- index funds

- ETFs

- REITs (real estate investment trusts)

- hedge funds

- commodities and alternative investments.

Stocks/shares

Firstly, ‘shares’ and ‘stocks’ are interchangeable terms. In North America they're often referred to as stocks, while ‘down under’ we go by shares.

A share is simply a small piece of a company; when a company sells a portion of its ownership, it does so by issuing stocks/shares. When someone says ‘I'm investing in Apple' it means the same thing as ‘I'm buying Apple shares'. It also means ‘I'm a shareholder of Apple'.

Having a small piece of a company technically makes you a shareholder of a company, meaning you own that small portion of the company. So if you bought a share of Apple and Twitter today, you'd own part (albeit a tiny part) of these companies. Better update your LinkedIn profile.

By being a shareholder of any company, you get to reap the rewards of that business's success: if it makes a profit you may get paid dividends, and if the company does well, the stock price usually goes up over time. But this also means you get to deal with the downfalls of a company; when the company lands in hot water, its price can sometimes falter too. For example, when you buy $1000 worth of Boeing shares, there is a risk that your $1000 is going to drop if a Boeing plane has a malfunction that reflects poorly on the company.

Shares are known to be a bit volatile compared to the other investing types we'll get into, such as funds or bonds. It's because they are at their core just one investment type. When it comes to the saying ‘don't put all your eggs in one basket', it's often referring to the idea that it may not be wise to only hold shares of one company in your entire portfolio. Even five companies aren't enough, but we'll get into that in chapter 9 when we speak about diversifying.

Shareholders also get to have a say in how the company runs, but to a pretty small scale. You can go to shareholder meetings, although these are often virtual, and vote on how the company is run.

The voting includes stock‐standard items such as electing the board of directors. Yes, that's right, you can technically vote Larry Page off Google's board. Their 2021 meeting, for example, voted on appointing their accounting firm, Ernst and Young, and whether they should add a human rights and/or civil rights expert to the board. (Interestingly enough, there were more votes against it than for it.) You don't have to go to these meetings, but I highly recommend attending one for the sake of it. And yes, they’re over Zoom.

Stocks are broken down into a range of categories, but the six most common are as follows:

- Growth stocks: These are usually tech companies that are trying to grow quicker than the rest of the stocks in their sector. These are like potential romantic partners that are a bit wild and spontaneous; you don't know what you're going to get and you may crash and burn. High risk with the potential for high reward.

- Blue Chip stocks: These are the partners your parents want you to end up with. They're established, stable and reliable, with a strong reputation (e.g. Disney stock).

- Sector stocks: Stocks can be broken down by sector, such as stocks in healthcare (e.g. pharmacy companies), utilities, IT, energy, pharmaceuticals, materials, financials and consumer discretionaries or staples.

- Large cap stocks: Market capitalisation is how much a company is worth (e.g. $1 billion or $5 billion). Companies that are worth over $10 billion are large cap. Stocks in large cap companies tend to be more stable, but don't grow as fast (e.g. Alphabet stock).

- Mid cap stocks: Companies with a market capitalisation between $2 and $10 billion. They're a mixture of the benefits and drawbacks you'd see in both large cap and small cap stocks. The best of both worlds, as Hannah Montana would say.

- Small cap stocks: Companies with a market capitalisation of less than $2 billion. These stocks are the most volatile but can provide high reward for high risk. They're essentially like startups. Most fail but some ‘shoot to the moon’ and provide great returns.

Stocks can be thought of as the purest form of investing: choosing a company and putting your money on the line to back them.

Bonds

If stocks are the party animals of the world, bonds are the studious, quiet types. They don't bother anyone, they do what they say they'll do, and, sadly, they're often left out of the equation until things start to fall apart.

Bonds are when you get to act like a bank and loan your money to a government or company. With bonds, the company or government are basically asking you to loan them money. They'll pay it back to you with a fixed amount of interest to say thank you for letting them borrow it. In fancy terms bonds are a debt instrument (think of an ‘instrument’ like a service) representing a loan by you, the investor, to a borrower, such as a government.

Companies and organisations use the money raised through bonds to finance their work. Companies issue corporate bonds and governments issue municipal bonds, but the way they both work is very much the same. The bond rates are affected by interest rates, so when interest rates rise, people tend to buy more bonds. You buy your bond at an agreed interest rate, then you get paid your fixed interest (e.g. 2 per cent) no matter what the climate of the world is, unlike shares where the returns you get fluctuate. After the agreed amount of time, you get your initial money back. This initial money is called your principal.

Bonds are much less risky than stocks. One way I remember this is thinking ‘the government can't not pay me back if I lend them money — it'll make them look bad!' However, due to the lower risk of them ghosting you, they give you a lower return on your money. You'll notice this trend a lot through this book: if you want to increase your chance of making more gains, you need to factor in more risk. Investors in training know they can't quite have their cake and eat it too.

Mutual funds

Rather than holding your money in individual companies, you can put a bunch of companies together in a basket and invest in a piece of that basket, called a fund. This is where mutual funds come in. Mutual funds (also known as managed funds) are baskets that can be filled with many different combinations of stocks, bonds, cash or cash equivalents, and other investments.

Some mutual funds have these companies chosen by a computer (e.g. an index fund), while other mutual funds are actively managed by a human being. For the purpose of this book, when I say ‘mutual funds’, I'm referring to actively managed mutual funds, as that is what most personal finance jargon refers to. But technically mutual funds are just a management style. A mutual fund can be an actively managed fund as well as a passive index fund. Technically it is incorrect to assume all mutual funds are actively managed, but for the purpose of simplicity we’ll assume the mutual funds we speak about are in fact actively managed.

Mutual funds pool money from many investors and invest them on their behalf. One mutual fund could be a basket of tech stocks or energy stocks. It could be a basket of high‐growth companies or more stable companies. You can buy a ‘share’ of a mutual fund in the same way that you can buy a share of a company; only instead of buying a piece of a company, you're buying a piece of the basket of stocks. (It's worth noting these funds don't always have to invest in stocks — they can also be made up of bonds or other types of investments.)

How do actively managed mutual funds choose their stocks? Imagine a person is tasked with the job of selecting the best berries on a farm. They examine the berries and clear them of anything that makes them unattractive, thus screening through all the berries and only putting the best ones in the basket. This is what the fund manager is trying to do. It is someone's full‐time job to screen hundreds of companies to try and find the ones that are going to beat the average returns you'd get from the stock market.

Because mutual funds involve people who spend time doing a lot of work, and need offices and spaces to work, these funds tend to have higher fees. Fund managers on average take a 1.4 per cent fee of a portfolio. This may not seem like a lot, but the fee is taken regardless of whether the fund makes you a profit. They are also a lot higher than what you'd be paying in a fund that isn't actively managed, which can sit as low as 0.03 per cent.

Let me tell you a little secret. It's human nature to assume that actively managed funds are more likely to do well, since the fund managers do so much work analysing companies and charge high fees. That's how things are meant to work right? The higher the fee, the more work put in, the better the outcome?

Funnily enough, mutual funds have a lot in common with high‐end moisturisers: the cheaper ones do just as well, if not better.

Mutual funds can sometimes do better in the short term, but rarely in the long term. In fact, a study done in 2018 by Standard and Poor’s (S&P) Research Group found that over a 15‐year investment horizon, only 2.3 to 7.57 per cent of actively managed mutual funds beat the passive index funds (which we'll get into next). Actively managed funds are managed by professionals, who are highly qualified and skilled, equipped with the best software in the world to try and beat the market, and only 2.3 to 7.57 per cent actually get it right.

Investors in training know that despite costing more in fees, actively managed mutual funds usually do as well as or worse than index funds that are cheaper and require less time in research — a fund manager spending 50 hours a week to find the best companies to invest in is spending a lot more time than a passively managed index fund.

Index funds

Index funds are like that humble, low‐key friend who is actually a secret superhero, volunteering all their time at the hospital and making you care packages when you're sick. Index funds used to be the overlooked part of the investing world. Funnily enough, they were invented by someone who was sick of mutual funds.

John Bogle, the founder of the Vanguard Group, which is now one of the world's most popular investment management companies, decided to create a type of mutual fund that stripped away all the active investing and instead made it as passive as possible. Though, mind you, Vanguard still has some actively managed funds to this day!

In 1976, Bogle decided that computers were the solution and, rather than relying on someone to spend hours trying to decide what companies to invest in, an automatic system could do it better.

Bogle proposed that instead of trying to beat the market, why not try and be the market? His index fund, which was essentially a basket made of the top 500 companies in the US, now called the S&P 500, ended up becoming a huge success.

See, an index fund follows an index, which is just a list. You could follow the top 200 companies in Australia, with an index called the ASX 200, or the top 50 companies in New Zealand, called the NZ 50. You could follow the top 100 companies in the UK, called the FTSE 100, or the top 100 companies in India, the NIFTY 100 — the options of indexes are limitless. They also don't have to be a list of top companies; you can have funds that follow a list of only female‐run companies, or a list of the top ethical companies in the US.

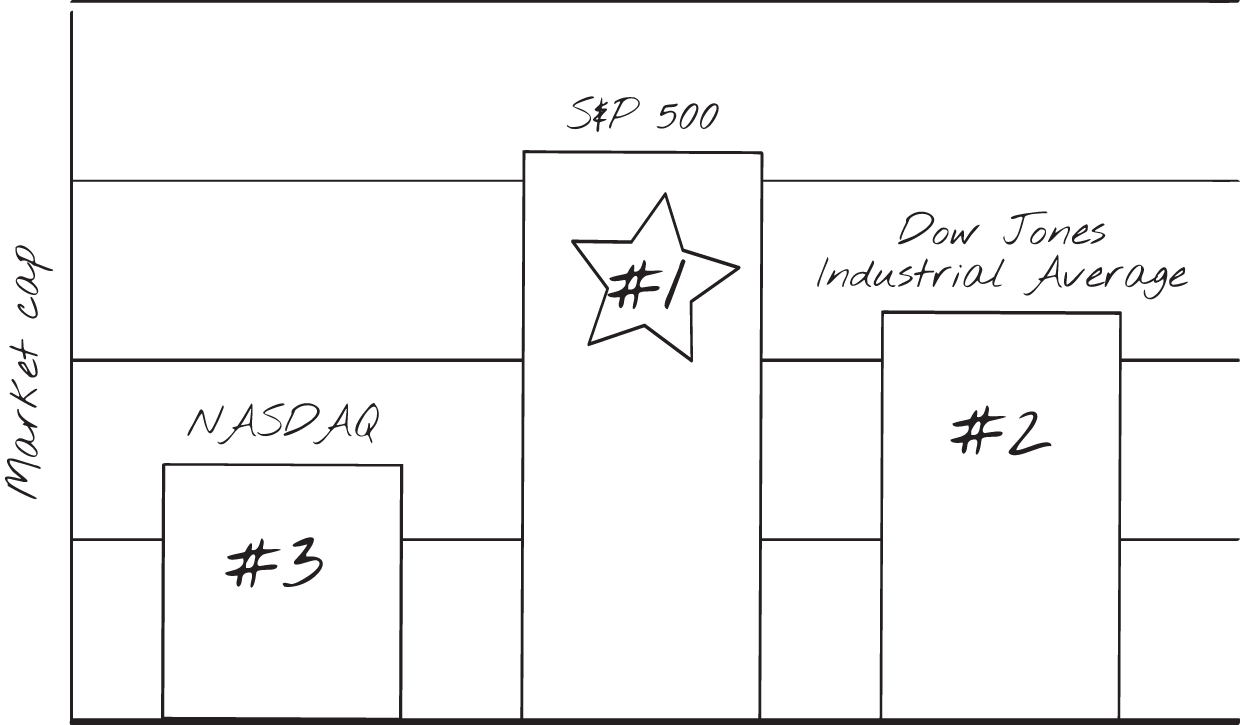

The three most common indexes are the S&P 500, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which follows the top 30 companies in the US, and NASDAQ, which follows the top 1000 tech companies in the US. These funds are often quoted to represent when the market moves (e.g. ‘the Dow is down 3 per cent’). See figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1: the top three indexes

You may have heard of an S&P 500 index fund. Different companies have their own funds based on the index, like Vanguard's S&P 500 fund or Smartshares' S&P 500 fund. They both invest in the same thing. It's like buying a plain black Nike shirt versus an identical plain black Adidas shirt: it's the same black shirt, just different branding. You can buy the fund through a broker (like buying the shirt through Asos or The Iconic) or from its investment company (e.g. buying the shirt directly from Nike or Adidas). In simple terms, these index funds are the world's most common funds and there are many variations of where and how to buy them — but more on that in ‘Putting it all together’.

An index fund is a type of mutual fund, but it's passively managed rather than actively managed. If company A surges in value and becomes a top 500 company, the portfolio automatically gets adjusted by investing into company A and kicking out company B, which was #500 on the list but is now #501.

It's simple. Since there's no need to have a person there to adjust the funds and go over which companies should and shouldn't be there, the fees associated with managing index funds are significantly lower. We like lower fees.

Both index funds and mutual funds have a high cost to entry, with mutual funds being the higher of the two. It's not uncommon to see a mutual fund that still asks for a $10 000 minimum entry into the fund, though you're more likely to see them asking around $1000 to $5000 to begin with.

And because you're investing in a basket of shares, rather than owning the shares directly, you don't have voting rights. (Look, it was unlikely that your one vote was going to push Larry Page off the Google executive board anyways.)

While index funds are technically a kind of mutual fund, in the general sense, when they are spoken about in the world of investing, most people refer to ‘mutual funds’ when they speak about actively managed funds and they refer to index funds as passive funds. Investors either love actively managed funds or passive index funds. They either believe actively chosen funds are going to provide them better outcomes in the long term, or that passive funds do better long term. While the evidence shows that the vast majority of actively managed funds do not outperform the index, some do. There's a wide range of reasons why someone may prefer to invest with an actively managed fund, but the most common come down to assuming that the higher cost must equate to better returns, the ‘human’ element of a fund manager, and the ability to quickly react to the market when things change.

A downside of index funds and mutual funds in general is that their price is valued at the end of the day, and buying/selling of these funds occur after the stock market closes for the day. This means if you wanted to invest at 9 am, you wouldn't be able to. And since index funds often have a minimum investment, you'd need to save up until you could deposit this money (e.g. if you have $100 but the fund is currently valued at $1000, you have to wait and save up $1000 before you can invest in that fund).

In the same way index funds were created to solve a problem, so were ETFs.

ETFs

ETFs or exchange‐traded funds, like myself, were introduced in the mid 1990s. They are similar to index funds, and ETFs can often invest in the exact same fund an index would.

In fact, more often than not, you can find an ETF that tracks an index fund. ETFs are like shadows to index funds.

For example, a Vanguard S&P 500 index fund also has a Vanguard S&P 500 ETF.

If the index fund goes up 10 per cent, so does the ETF.

If the index fund goes down 9 per cent, so does the ETF.

They invest in the same thing — so why do ETFs exist when index funds do the same job?

There are two important reasons:

- lower barrier to entry

- you can buy and sell throughout the day, not just when the market has closed.

Remember that idea of fractional shares, where can you buy a small per cent of one share for as little as $1? That's the same with ETFs. ETFs bypass the minimum $1000 usually needed to buy into index funds. You get to buy a fraction of the basket at a fraction of the cost. This is helpful when you have less money to invest with, and don't want to only be investing every time you save up $1000. With ETFs you can invest in those baskets with $10 or even $1 if you wished to.

The other issue with index funds and mutual funds in general is that they give you one price every day, and you take it or leave it. With ETFs, however, their price varies throughout the day. This also means you can sell it or buy it throughout the day. It's not a huge bother, but it's one of the main differences between index funds and ETFs.

Since ETFs are fan favourites, there are quite a few types of ETFs out there. Let's go over some of the common ones:

- market ETFs: they invest in indexes, like the S&P 500

- bond ETFs: you can buy a basket of bonds (remember bonds as those loans you give to governments or organisations) as an ETF

- sector ETFs: these are ETFs that invest in just one sector, like a basket of just healthcare companies or a basket of just car companies; the most common type is a basket of tech companies

- foreign market ETFs: these let you invest in overseas companies outside of your home country

- actively managed ETFs: yup, to throw everything you've just learned into the gutter, sometimes ETFs can be actively managed too. They're not always following an index fund. These ETFs are basically like actively managed mutual funds, but you can buy a per cent of them and their price varies throughout the day. Ark Innovative ETFs are currently the most well‐known actively managed ETFs on the market. Created by Cathie Wood, their goal is to try and beat the market ETFs by investing in emergent technology, such as stem cell research.

Funds (or baskets) can be used to hold more than just companies; they can also be used for real estate. Enter REITs.

REITs

REITs, or real estate investment trusts, are the funds of the real estate world. Rather than investing in a basket of companies, you now get to invest in a basket of real estate: usually commercial real estate, which is real estate that businesses hire for their companies or stores, rather than homes or apartments where people live.

REITs are a great way for people to get some exposure into the world of real estate without being a landlord. You don't have to manage the real estate, you don't have to deal with contracts or tenants. It doesn't matter if there is a leak in the roof — that is all dealt with.

REITs are also a good option for those who are uncomfortable with the idea of directly being a landlord for private property. By choosing commercial real estate REITs, the younger generations are expressing their moral stance in not owning rental homes. This book is not to judge or make that decision for you, but if you wish to step into real estate, REITs can be a good alternative.

REITs can be bought as mutual funds or as an ETF. Like ETFs, they can also be broken down into sectors. You may prefer to invest in just resorts or hospitals, or just in retail (e.g. a REIT made out of malls).

The reason REITs can be an attractive option is that they provide high‐yield dividends, which can be thought of as the equivalent of rent. Rather than buying a commercial property yourself and getting rent from a tenant, you buy a REIT and get a dividend. Some stocks provide dividends too, but REITs do this on a larger scale.

In the last 10 years, the performance of US REITs based on the FTSE NAREIT Equity REIT Index was 9.5 per cent. That's a mouthful, but what it means is that the return was less than or equal to what the broad stock market brought over that 10‐year period, so it shouldn't replace your entire portfolio.

It's worth noting that when it comes to physical real estate, ‘real’ real estate investing often beats out a 9.5 per cent gain, if you leverage. Leverage is the fancy word to say you're using the bank's money to grow your money. For example, say you owned a $500 000 home and you put down a $50 000 deposit. If the house went up 10 per cent the next year, you made a 10 per cent return on the total value of the house, not a 10 per cent return on your $50 000 deposit. This would leave you with a $50 000 return on the original $50 000 you put down. Whereas if you had invested $50 000 in the share market and made a 10 per cent gain, that is only on the $50 000 invested. This would leave you with a $5000 return on your original $50 000 you put down. Leverage can be powerful.

So if you're looking to make big money through real estate, REITs aren't the way to do it. But if you're looking to diversify your stock market portfolio with real estate, REITs fit in quite nicely.

Another benefit of REITs is that, unlike buying or selling physical real estate yourself, which is a process that can take a few months or even a year, REITs are easy to buy and sell. You can have your money in real estate while having a lot more liquidity. (I like to think of liquidity like literal liquid; the more liquidity an investment type has, the easier it is to ‘swish around’ from one account to another.)

One thing to note about REITs is that they're more sensitive to interest rates and can drop quickly when rates rise. In some countries such as the US, their dividends are also taxed at a higher rate than the dividends of stocks.

Hedge funds

Most people, whether they have invested or not, have heard of the mysterious, exclusive hedge fund.

Hedge funds used to really confuse me. The first time I heard of them I thought they were related to hedges or gated communities. Then I felt like maybe they were so hard to get into because they were protected by ‘hedges’. You couldn't have paid me to guess what a hedge fund did.

Eventually I learned that, in essence, hedge funds are just mutual funds — but on steroids. They are run by investment fund managers who are allowed to make riskier investments on behalf of their investors in the hope that they outperform the market average. This means they get to invest in ways that normal investors don't always have access to, unless we have a net worth of more than $1 million.

A hedge fund is still a basket, but rather than a basket just filled with some companies that the fund managers think will do better, it's filled with shinier, newer, more interesting and riskier products that they hope will do better, such as investing in real estate, derivatives or even currencies, among other ‘riskier’ asset types. If our S&P 500 index fund was a straw basket, a hedge fund is a gold‐plated Hermès Birkin bag.

As a result, hedge funds are notoriously expensive to invest in. They also take a whoppingly high cut of profits — 20 per cent. It makes the 1 to 2 per cent cut from mutual fund managers look like pennies. In fact, the top 15 hedge fund managers together earned an estimated $23.2 billion in 2020 during the COVID pandemic, according to Bloomberg News. The head of Tiger Global Management alone made $3 billion. Not bad for a pandemic year.

Whether it's a straw basket or a Birkin bag, it actually doesn't matter how much the bag costs (or how much the fees are) — what truly matters is what's inside.

A hedge fund's main purpose is to maximise returns and remove as much risk as possible.

They're called hedge funds, not because of anything related to plants, but rather due to a technique called ‘hedging’. You may have heard people say they're ‘hedging their bets’, meaning they're trying to minimise their risk. Hedging is an investment technique to offset the risk of other investments. For example, if you invest in Apple in the hope that it goes up, you can also hedge your bet so that if it goes down in price, you still make money regardless.

Hedge funds basically try to make money regardless of whether the market goes up or down. It's kind of clever.

So are they worth the hype and all those fees?

In 2008, Warren Buffett, one of the most successful stock market investors in the world, made a 10‐year bet to see if hedge funds could beat someone investing in the S&P 500. Warren chose Vanguard's S&P 500 Admiral fund (an index fund that goes by the ticker VFIAX). (A ticker is a symbol made up of two to five letters given to every stock or fund, a bit like a car numberplate, e.g. GOOG for Google.)

Buffett believed that including fees, costs and expenses, passive investing into the S&P 500 was a better strategy than active investing, given their notoriously high fees and the lack of data that supports active investing. Buffett found a hedge fund, Protégé Partners, to take on the bet. The loser would have to donate $1 million to charity. So who would win: the passive index fund or the exclusive and prestigious hedge fund?

In May of 2017, several months before the competition ended, the hedge fund owner wrote an open letter: ‘the game is over, I lost’.

It was a huge shock to the investment industry that a passive fund with a fee of 0.04 per cent could outperform a hedge fund that would be charging 2 per cent in fees and 20 per cent of profits. Billions are poured into the hedge fund industry, and yet a passive investor with access to an S&P 500 index fund or ETF could outperform hedge funds? Phenomenal.

It again highlighted the misconception that to make money in the stock market you need a lot of money to start with, or that you need to do a lot of work to invest. It just isn't true, and the sooner investors in training realise that they do not need a net worth of $1 million to begin investing, the better.

Now that we have the most popular investment types down, are there any other investments to consider?

Commodities and alternative investments

To put it simply, commodities are types of investments that help provide more diversification and they help to hedge against inflation. We don't like inflation in the stock market as it can cause stock prices to pull down. It sounds a bit counterintuitive as inflation is known to raise prices of goods and services — but for a company, this means more costly materials and thus lower profits, hence lower share prices. Commodities are stocks in physical things: metals like gold and silver, agricultural products like wheat and livestock, and energy like crude oil and natural gas. You can buy commodities directly, and the most common way to do so is through stocks or funds (e.g. an energy ETF).

Alternative investments

While traditional investing methods include stocks, bonds and cash, alternative methods include non‐traditional approaches to investing. (Technically, hedge funds are alternative investments but I felt like they deserved a section of their own.)

Items such as art, cars, handbags, cryptocurrency and NFTs (the latter two are covered more in chapter 11) are also alternative investments.

That's right. Even luxury bags can be alternative investments. Hermès Birkin bags are so rare they can outperform the market. A crocodile skin Birkin, which can cost anywhere between $60 000 and $200 000, can see an annual return of 14.2 per cent. According to BagHunter, Birkin bags have outperformed the S&P 500 for the last 35 years. The most expensive purchase was a white gold and diamond Birkin selling for $372 000 in 2016. (Now it makes sense why Kris Jenner's wardrobe features a neon sign saying ‘Need Money for Birkin’.)

For an investor in training, alternative investments are something we shouldn't be giving too much attention to at the start, especially as the barrier to entry is high. Most of us don't start out with $10 000 to put into a luxury bag or a Picasso piece.

***

In the world of investing, there are many types of investments that investors in training have access to — from index funds to ETFs, REITs to commodities. Once broken down in easy‐to‐understand language, the structure of these investments is digestible even for the most novice investor.