Chapter 2

THE MONEY MARKETS

Part of the global debt capital markets, the money markets are a separate market in their own right. Money market securities are defined as debt instruments with an original maturity of less than 1 year, although it is common to find that the maturity profile of banks’ money market desks runs out to 2 years.

Money markets exist in every market economy, which is practically every country in the world. They are often the first element of a developing capital market. In every case they are comprised of securities with maturities of up to 12 months. Money market debt is an important part of global capital markets, and facilitates the smooth running of the banking industry as well as providing working capital for industrial and commercial corporate institutions. The market provides users with a wide range of opportunities and funding possibilities, and the market is characterized by the diverse range of products that can be traded within it. Money market instruments allow issuers, including financial organizations and corporates, to raise funds for short-term periods at relatively low interest rates. These issuers include sovereign governments, who issue Treasury bills, corporates issuing commercial paper and banks issuing bills and certificates of deposit. At the same time, investors are attracted to the market because the instruments are highly liquid and carry relatively low credit risk. The Treasury bill market in any country is that country’s lowest risk instrument, and consequently carries the lowest yield of any debt instrument. Indeed, the first market that develops in any country is usually the Treasury bill market. Investors in the money market include banks, local authorities, corporations, money market investment funds and mutual funds, and individuals.

In addition to cash instruments, the money markets also consist of a wide range of exchange-traded and over-the-counter off-balance-sheet derivative instruments. These instruments are used mainly to establish future borrowing and lending rates, and to hedge or change existing interest rate exposure. This activity is carried out by both banks, central banks and corporates. The main derivatives are short-term interest rate futures, forward rate agreements and short-dated interest rate swaps, such as overnight index swaps.

In this chapter we review the cash instruments traded in the money market. In further chapters we review banking asset and liability management, and the market in repurchase agreements. Finally, we consider the market in money market derivative instruments including interest rate futures and forward rate agreements.

INTRODUCTION

The cash instruments traded in money markets include the following:

- time deposits;

- Treasury bills;

- certificates of deposit;

- commercial paper;

- banker’s acceptances;

- bills of exchange;

- repo and stock lending.

Treasury bills are used by sovereign governments to raise short-term funds, while certificates of deposit (CDs) are used by banks to raise finance. The other instruments are used by corporates and occasionally banks. Each instrument represents an obligation on the borrower to repay the amount borrowed on the maturity date together with interest if this applies. The instruments above fall into one of two main classes of money market securities: those quoted on a yield basis and those quoted on a discount basis. These two terms are discussed below. A repurchase agreement or ‘repo’ is also a money market instrument.

The calculation of interest in the money markets often differs from the calculation of accrued interest in the corresponding bond market. Generally, the day-count convention in the money market is the exact number of days that the instrument is held over the number of days in the year. In the UK sterling market the year base is 365 days, so the interest calculation for sterling money market instruments is given by (2.1):

However, the majority of currencies, including the US dollar and the euro, calculate interest on a 360-day base. The process by which an interest rate quoted on one basis is converted to one quoted on the other basis is shown on p. 68. Those markets that calculate interest based on a 365-day year are also listed on p. 68.

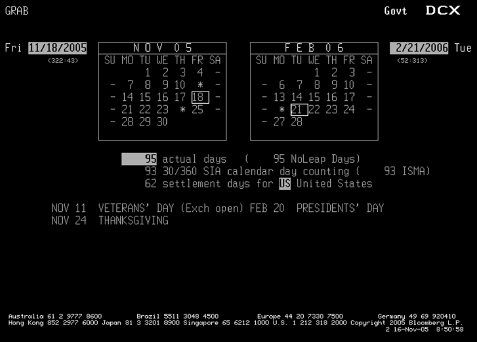

Dealers will want to know the interest day base for a currency before dealing in it as foreign exchange (FX) or money markets. Bloomberg users can use screen DCX to look up the number of days of an interest period. For instance, Figure 2.1 shows screen DCX for the US dollar market, for a loan taken out on 16 November 2005 for spot value on 18 November 2005 for a straight 3-month period. This matures on 21 February 2006; we see from Figure 2.1 that this is a good day. We see also that 20 February 2006 is a USD holiday. The loan period is actually 95 days, and 93 days under the 30/360-day convention (a bond market accrued interest convention). The number of business days is 62.

Figure 2.1 Bloomberg screen DCX used for US dollar market, 3-month loan taken out for value 18 November 2005.

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

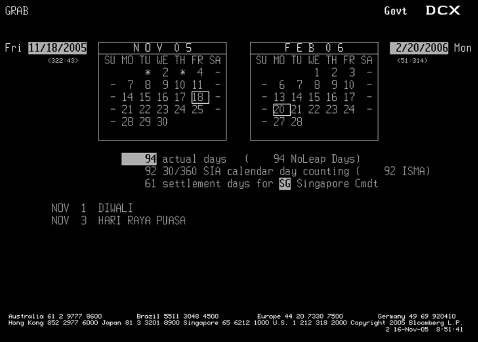

For the same loan taken out in Singapore dollars, look at Figure 2.2. This shows that 20 February 2006 is not a public holiday for SGD and so the loan runs for the period 18 December 2005 to 20 February 2006.

Figure 2.2 Bloomberg screen DCX for Singapore dollar market, 3-month loan taken out for value 18 November 2005.

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Settlement of money market instruments can be for value today (generally only when traded before mid-day), tomorrow or 2 days forward, which is known as spot. The latter is most common.

SECURITIES QUOTED ON A YIELD BASIS

Two of the instruments in the list at the top of p. 25 are yield-based instruments.

Money market deposits

These are fixed interest term deposits of up to 1 year with banks and securities houses. They are also known as time deposits or clean deposits. They are not negotiable so cannot be liquidated before maturity. The interest rate on the deposit is fixed for the term and related to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) of the same term. Interest and capital are paid on maturity.

LIBOR

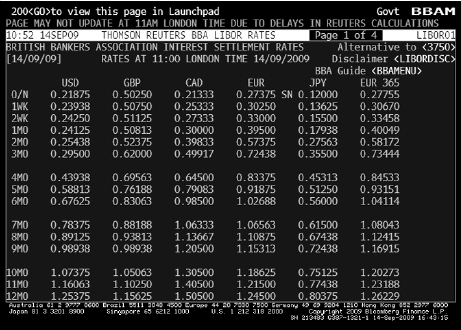

The term LIBOR or ‘Libor’ comes from London Interbank Offered Rate and is the interest rate at which one London bank offers funds to another London bank of acceptable credit quality in the form of a cash deposit. The rate is ‘fixed’ by the British Bankers Association at 11a.m. every business day morning (in practice, the fix is usually about 20 minutes later) by taking the average of the rates supplied by member banks. The term LIBID is the bank’s ‘bid’ rate – that is, the rate at which it pays for funds in the London market. The quote spread for a selected maturity is therefore the difference between LIBOR and LIBID. The convention in London is to quote the two rates as LIBOR–LIBID, thus matching the yield convention for other instruments. In some other markets the quote convention is reversed. EURIBOR is the interbank rate offered for euros as reported by the European Central Bank, fixed in Brussels. Figure 2.3 shows the Bloomberg screen BBAM, which is the daily listing of the BBA Libor fix, as at 14 September 2009.

Figure 2.3 British Bankers’ Association Libor fixing, Bloomberg page BBAM, as at 14 September 2009.

© 2009 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The effective rate on a money market deposit is the annual equivalent interest rate for an instrument with a maturity of less than 1 year.

Example 2.1

A sum of 250,000 is deposited for 270 days, at the end of which the total proceeds are 261,000. What are the simple and effective rates of return on a 365-day basis?

Certificates of deposit

Certificates of deposit (CDs) are receipts from banks for deposits that have been placed with them. They were first introduced in the sterling market in 1958. The deposits themselves carry a fixed rate of interest related to LIBOR and have a fixed term to maturity, so cannot be withdrawn before maturity. However, the certificates themselves can be traded in a secondary market – that is, they are negotiable.1 CDs are therefore very similar to negotiable money market deposits, although the yields are about 0.15% below the equivalent deposit rates because of the added benefit of liquidity. Most CDs issued are of between 1 and 3 months’ maturity, although they do trade in maturities of 1 to 5 years. Interest is paid on maturity except for CDs lasting longer than 1 year, where interest is paid annually or, occasionally, semiannually.

Banks, merchant banks and building societies issue CDs to raise funds to finance their business activities. A CD will have a stated interest rate and fixed maturity date, and can be issued in any denomination. On issue a CD is sold for face value, so the settlement proceeds of a CD on issue are always equal to its nominal value. The interest is paid, together with the face amount, on maturity. The interest rate is sometimes called the coupon, but unless the CD is held to maturity this will not equal the yield, which is of course the current rate available in the market and varies over time. The largest group of CD investors are banks, money market funds, corporates and local authority treasurers.

Unlike coupons on bonds, which are paid in rounded amounts, CD coupon is calculated to the exact day.

CD yields

The coupon quoted on a CD is a function of the credit quality of the issuing bank, its expected liquidity level in the market and, of course, the maturity of the CD, as this will be considered relative to the money market yield curve. As CDs are issued by banks as part of their short-term funding and liquidity requirement, issue volumes are driven by the demand for bank loans and the availability of alternative sources of funds for bank customers. The credit quality of the issuing bank is the primary consideration, however; in the sterling market the lowest yield is paid by ‘clearer’ CDs, which are CDs issued by the clearing banks – such as RBS NatWest plc, HSBC and Barclays plc. In the US market ‘prime’ CDs, issued by highly rated domestic banks, trade at a lower yield than non-prime CDs. In both markets CDs issued by foreign banks – such as French or Japanese banks – will trade at higher yields.

Euro-CDs, which are CDs issued in a different currency from that of the home currency, also trade at higher yields in the US because of reserve and deposit insurance restrictions.

If the current market price of the CD including accrued interest is and the current quoted yield is, the yield can be calculated given the price, using (2.2):

The price can be calculated given the yield using (2.3):

After issue a CD can be traded in the secondary market. The secondary market in CDs in the UK is very liquid, and CDs will trade at the rate prevalent at the time, which will invariably be different from the coupon rate on the CD at issue. When a CD is traded in the secondary market, the settlement proceeds will need to take into account interest that has accrued on the paper and the different rate at which the CD has now been dealt. The formula for calculating the settlement figure is given at (2.4) which applies to the sterling market and its 365 day-count basis:

The settlement figure for a new issue CD is, of course, its face value...!2

The tenor of a CD is the life of the CD in days, while days remaining is the number of days left to maturity from the time of trade.

The return on holding a CD is given by (2.5):

Example 2.2

A 3-month CD is issued on 6 September 1999 and matures on 6 December 1999 (maturity of 91 days). It has a face value of 20,000,000 and a coupon of 5.45%. What are the total maturity proceeds?

What are the secondary market proceeds on 11 October if the yield for short 60-day paper is 5.60%?

On 18 November the yield on short 3-week paper is 5.215%. What rate of return is earned from holding the CD for the 38 days from 11 October to 18 November?

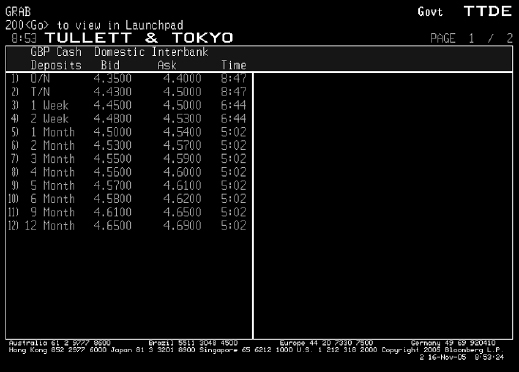

An example of the way CDs and time deposits are quoted on screen is shown at Figure 2.4, which shows one of the rates screens displayed by Tullett & Tokyo, money brokers in London, on a Bloomberg screen. Essentially the same screen is displayed on Reuters. The screen has been reproduced with permission from Tullett’s and Bloomberg. The screen displays sterling interbank and CD bid and offer rates for maturities up to 1 year as at 18 November 2005. The maturity marked ‘O/N’ is the overnight rate, which at that time was 4.35–4.40. The maturity marked ‘T/N’ is ‘tom-next’, or ‘tomorrow-to-the-next’, which is the overnight rate for deposits commencing tomorrow. Note that the liquidity of CDs means that they trade at a lower yield to deposits. The bid–offer convention in sterling is that the rate at which the market-maker will pay for funds – its borrowing rate – is placed on the left.A 6-month time deposit is lent at 4.62%.

Figure 2.4 Tullett & Tokyo brokers' sterling money markets screen, 18 November 2005.

© Tullett & Tokyo and Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

This is a reversal of the sterling market convention of placing the offered rate on the left-hand side, which existed until the end of the 1990s.

US dollar market rates

Treasury bills

The Treasury bill (T-bill) market in the US is the most liquid and transparent debt market in the world. Consequently, the bid–offer spread on them is very narrow. The Treasury issues bills at a weekly auction each Monday, made up of 91-day and 182-day bills. Every fourth week the Treasury also issues 52-week bills as well. As a result there are large numbers of T-bills outstanding at any one time. The interest earned on T-bills is not liable to state and local income taxes. T-bill rates are the lowest in the dollar market (as indeed any bill market is in respective domestic environments) and as such represent the corporate financier’s risk-free interest rate.

Federal funds

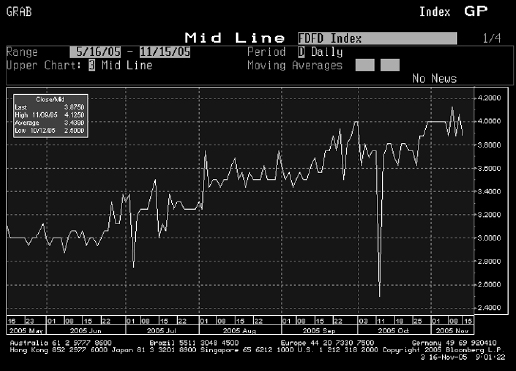

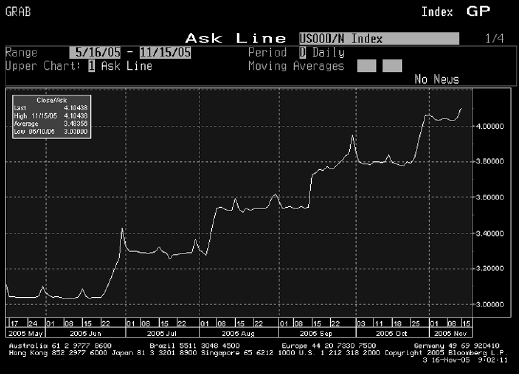

Commercial banks in the US are required to keep reserves on deposit at the Federal Reserve. Banks with reserves in excess of required reserves can lend these funds to other banks, and these interbank loans are called federal funds or fed funds and are usually overnight loans. Through the fed funds market, commercial banks with excess funds are able to lend to banks that are short of reserves, thus facilitating liquidity. The transactions are very large denominations, and are lent at the fed funds rate, which can be a relatively volatile interest rate because it fluctuates with market shortages. On average, it trades about 15 basis points or so below the overnight Libor fix. The difference can be gauged by looking at Figures 2.5 and 2.6, which are the graphs for historical USD fed funds and overnight Libor rates, respectively.

Figure 2.5 Bloomberg screen GP showing fed funds rate for period May–November 2005.

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 2.6 Bloomberg screen GP showing USD overnight Libor for period MayNovember 2005.

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Prime rate

The prime interest rate in the US is often said to represent the rate at which commercial banks lend to their most creditworthy customers. In practice, many loans are made at rates below the prime rate, so the prime rate is not the best rate at which highly rated firms may borrow. Nevertheless, the prime rate is a benchmark indicator of the level of US money market rates, and is often used as a reference rate for floating-rate instruments. As the market for bank loans is highly competitive, all commercial banks quote a single prime rate, and the rate for all banks changes simultaneously.

SECURITIES QUOTED ON A DISCOUNT BASIS

The remaining money market instruments are all quoted on a discount basis, and so are known as ‘discount’ instruments. This means that they are issued on a discount to face value, and are redeemed on maturity at face value. Hence T-bills, bills of exchange, banker’s acceptances and commercial paper are examples of money market securities that are quoted on a discount basis – that is, they are sold on the basis of a discount to par. The difference between the price paid at the time of purchase and the redemption value (par) is the interest earned by the holder of the paper. Explicit interest is not paid on discount instruments, rather interest is reflected implicitly in the difference between the discounted issue price and the par value received at maturity.

Treasury bills

Treasury bills (T-bills) are short-term government ‘IOUs’ of short duration, often 3-month maturity. For example, if a bill is issued on 10 January it will mature on 10 April. Bills of 1-month and 6-month maturity are issued in certain markets, but only rarely by the UK Treasury. On maturity the holder of a T-bill receives the par value of the bill by presenting it to the central bank. In the UK most such bills are denominated in sterling but issues are also made in euros. In a capital market, T-bill yields are regarded as the risk-free yield, as they represent the yield from short-term government debt. In emerging markets they are often the most liquid instruments available for investors.

A sterling T-bill with 10 million face value issued for 91 days will be redeemed on maturity at 10 million. If the 3-month yield at the time of issue is 5.25%, the price of the bill at issue is:

In the UK market the interest rate on discount instruments is quoted as a discount rate rather than a yield. This is the amount of discount expressed as an annualized percentage of the face value, and not as a percentage of the original amount paid. By definition, the discount rate is always lower than the corresponding yield. If the discount rate on a bill is, then the amount of discount is given by (2.6):

The price paid for the bill is the face value minus the discount amount, given by (2.7):

If we know the yield on the bill then we can calculate its price at issue by using the simple present value formula, as shown at (2.8):

The discount rate for T-bills is calculated using (2.9):

The relationship between discount rate and true yield is given by (2.10):

Example 2.3

A 91-day 100 T-bill is issued with a yield of 4.75%. What is its issue price?

A UK T-bill with a remaining maturity of 39 days is quoted at a discount of 4.95% What is the equivalent yield?

If a T-Bill is traded in the secondary market, the settlement proceeds from the trade are calculated using (2.11):

Banker’s acceptances

A banker’s acceptance is a written promise issued by a borrower to a bank to repay borrowed funds. The lending bank lends funds and in return accepts the banker’s acceptance. The acceptance is negotiable and can be sold in the secondary market. The investor who buys the acceptance can collect the loan on the day that repayment is due. If the borrower defaults, the investor has legal recourse to the bank that made the first acceptance. Banker’s acceptances are also known as bills of exchange, bank bills, trade bills or commercial bills.

Essentially, banker’s acceptances are instruments created to facilitate commercial trade transactions. The instrument is called a banker’s acceptance because a bank accepts the ultimate responsibility to repay the loan to its holder. The use of banker’s acceptances to finance commercial transactions is known as acceptance financing. The transactions for which acceptances are created include import and export of goods, the storage and shipping of goods between two overseas countries, where neither the importer nor the exporter is based in the home country,3 and the storage and shipping of goods between two entities based at home. Acceptances are discount instruments and are purchased by banks, local authorities and money market investment funds.

The rate that a bank charges a customer for issuing a banker’s acceptance is a function of the rate at which the bank thinks it will be able to sell it in the secondary market. A commission is added to this rate. For ineligible banker’s acceptances (see below) the issuing bank will add an amount to offset the cost of additional reserve requirements.

Eligible banker’s acceptance

An accepting bank that chooses to retain a banker’s acceptance in its portfolio may be able to use it as collateral for a loan obtained from the central bank during open market operations – for example, the Bank of England in the UK and the Federal Reserve in the US. Not all acceptances are eligible to be used as collateral in this way, as they must meet certain criteria set by the central bank. The main requirement for eligibility is that the acceptance must be within a certain maturity band (a maximum of 6 months in the US and 3 months in the UK), and that it must have been created to finance a self-liquidating commercial transaction. In the US eligibility is also important because the Federal Reserve imposes a reserve requirement on funds raised via banker’s acceptances that are ineligible. Banker’s acceptances sold by an accepting bank are potential liabilities for the bank, but the reserve imposes a limit on the amount of eligible banker’s acceptances that a bank may issue. Bills eligible for deposit at a central bank enjoy a finer rate than ineligible bills, and also act as a benchmark for prices in the secondary market.

COMMERCIAL PAPER

Commercial paper (CP) is a short-term money market funding instrument issued by corporates. In the UK and US it is a discount instrument. A company’s short-term capital and working capital requirement is usually sourced directly from banks, in the form of bank loans. An alternative short-term funding instrument is CP, which is available to corporates that have a sufficiently strong credit rating. CP is a short-term unsecured promissory note. The issuer of the note promises to pay its holder a specified amount on a specified maturity date. CP normally has a zero coupon and trades at a discount to its face value. The discount represents interest to the investor in the period to maturity. CP is typically issued in bearer form, although some issues are in registered form.

Originally, the CP market was restricted to borrowers with high credit ratings, and although lower rated borrowers do now issue CP, sometimes by obtaining credit enhancements or setting up collateral arrangements, issuance in the market is still dominated by highly rated companies. The majority of issues are very short term, from 30 to 90 days in maturity; it is extremely rare to observe paper with a maturity of more than 270 days or 9 months. This is because of regulatory requirements in the US,4 which state that debt instruments with a maturity of less than 270 days need not be registered. Companies therefore issue CP with a maturity lower than 9 months and so avoid the administration costs associated with registering issues with the SEC.

There are two major markets, the US dollar market with an outstanding amount in 2005 just under $1 trillion, and the Eurocommercial paper market with an outstanding value of $490 billion at the end of 2005.5 Commercial paper markets are wholesale markets, and transactions are typically very large. In the US over a third of all CP is purchased by money market unit trusts, known as mutual funds; other investors include pension fund managers, retail or commercial banks, local authorities and corporate treasurers. A comparison between USCP and ECP is given in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Comparison of US CP and Eurocommercial CP.

| Currency | US dollar | Any euro currency |

| Maturity | 1–270 days | 2–365 days |

| Common maturity | 30–180 days | 30–90 days |

| Interest | Zero coupon, issued at discount | Fixed coupon |

| Quotation | On a discount rate basis | On a yield basis |

| Settlement | T + 0, T + 1 | T + 2 |

| Registration | Bearer form | Bearer form |

| Negotiable | Yes | Yes |

Although there is a secondary market in CP, very little trading activity takes place since investors generally hold CP until maturity. This is to be expected because investors purchase CP that matches their specific maturity requirement. When an investor does wish to sell paper, it can be sold back to the dealer or, where the issuer has placed the paper directly in the market (and not via an investment bank), it can be sold back to the issuer.

Commercial paper programmes

The issuers of CP are often divided into two categories of company: banking and financial institutions and non-financial companies. The majority of CP issues are by financial companies. Financial companies include not only banks but also the financing arms of corporates – such as British Airways, BP and Ford Motor Credit. Most of the issuers have strong credit ratings, but lower rated borrowers have tapped the market, often after arranging credit support from a higher rated company, such as a letter of credit from a bank, or by arranging collateral for the issue in the form of high-quality assets such as Treasury bonds. CP issued with credit support is known as credit-supported commercial paper, while paper backed with assets is known naturally enough as asset-backed commercial paper. Paper that is backed by a bank letter of credit is termed LOC paper. Although banks charge a fee for issuing letters of credit, borrowers are often happy to arrange for this, since by so doing they are able to tap the CP market. The yield paid on an issue of CP will be lower than that on a commercial bank loan.

Although CP is a short-dated security, typically of 3-to-6-month maturity, it is issued within a longer term programme, usually for 3 to 5 years for euro paper; US CP programmes are often open-ended. For example, a company might arrange a 5-year CP programme with a limit of $100 million. Once the programme is established the company can issue CP up to this amount – say, for maturities of 30 or 60 days. The programme is continuous and new CP can be issued at any time, daily if required. The total amount in issue cannot exceed the limit set for the programme. A CP programme can be used by a company to manage its short-term liquidity – that is, its working capital requirements. New paper can be issued whenever a need for cash arises, and for an appropriate maturity.

Issuers often roll over their funding and use funds from a new issue of CP to redeem a maturing issue. There is a risk that an issuer might be unable to roll over the paper where there is a lack of investor interest in the new issue. To provide protection against this risk issuers often arrange a standby line of credit from a bank, normally for all of the CP programme, to draw against in the event that it cannot place a new issue.

There are two methods by which CP is issued, known as direct-issued or direct paper and dealer-issued or dealer paper. Direct paper is sold by the issuing firm directly to investors, and no agent bank or securities house is involved. It is common for financial companies to issue CP directly to their customers, often because they have continuous programmes and constantly roll over their paper. It is therefore cost-effective for them to have their own sales arm and sell their CP direct. The treasury arms of certain non-financial companies also issue direct paper; this includes, for example, British Airways plc corporate treasury, which runs a continuous direct CP programme, used to provide short-term working capital for the company. Dealer paper is paper that is sold using a banking or securities house intermediary. In the US, dealer CP is effectively dominated by investment banks, as retail (commercial) banks were until recently forbidden from underwriting commercial paper. This restriction has since been removed and now both investment banks and commercial paper underwrite dealer paper.

Commercial paper yields

CP is sold at a discount to its maturity value, and the difference between this maturity value and the purchase price is the interest earned by the investor. The CP day-count base is 360 days in the US and euro markets, and 365 days in the UK. The paper is quoted on a discount yield basis, in the same manner as T-bills. The yield on CP follows that of other money market instruments and is a function of the short-dated yield curve. The yield on CP is higher than the T-bill rate; this is due to the credit risk that the investor is exposed to when holding CP, for tax reasons (in certain jurisdictions interest earned on T-bills is exempt from income tax) and because of the lower level of liquidity available in the CP market. CP also pays a higher yield than CDs, due to the lower liquidity of the CP market.

Although CP is a discount instrument and trades as such in the US and UK, euro currency eurocommercial paper trades on a yield basis, similar to a CD. The expressions below illustrate the relationship between true yield and discount rate:

(2.12)

(2.13) ![]()

(2.14)

where is the face value of the instrument, is the discount rate and the true yield.

Example 2.4

1.A 60-day CP note has a nominal value of 100,000. It is issued at a discount of 7% per annum. The discount is calculated as:

The issue price for the CP is therefore 100,000 – 1,232, or

98,768. The money market yield on this note at the time of issue is:

![]()

Another way to calculate this yield is to measure the capital gain (the discount) as a percentage of the CP’s cost, and convert this from a 60-day yield to a 1-year (365-day) yield, as shown below:

2.ABC plc wishes to issue CP with 90 days to maturity. The investment bank managing the issue advises that the discount rate should be 9.5%. What should the issue price be, and what is the money market yield for investors?

The issue price will be 97.658.

The yield to investors will be:

![]()

Asset-backed commercial paper

The rise in securitization has led to the growth of short-term instruments backed by cashflows from other assets, known as asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). Securitization is the practice of using cash flows from a specified asset, such as residential mortgages, car loans or commercial bank loans, as backing for an issue of bonds. The assets themselves are transferred from the original owner (the originator) to a specially created legal entity known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV), so as to make them separate and bankruptcy-remote from the originator. In the meantime, the originator is able to benefit from capital market financing, often charged at a lower rate of interest than that earned by the originator on its assets. Securitized products are not money market instruments, and although ABCP is, most textbooks treat ABCP as part of the structured products market rather than as a money market product.

Generally, securitization is used as a funding instrument by companies for three main reasons: it offers lower cost funding compared with a traditional bank loan or bond financing; it is a mechanism by which assets such as corporate loans or mortgages can be removed from the balance sheet, thus improving the lender’s return on assets or return on equity ratios; and it increases a borrower’s funding options. When entering into securitization, an entity may issue term securities against assets into the public or private market, or it may issue commercial paper via a special vehicle known as a conduit. These conduits are usually sponsored by commercial banks.

Entities usually access the commercial paper market in order to secure permanent financing, rolling over individual issues as part of a longer term programme and using interest rate swaps to arrange a fixed rate if required. Conventional CP issues are typically supported by a line of credit from a commercial bank, and so this form of financing is in effect a form of bank funding. Issuing ABCP enables an originator to benefit from money market financing that it might otherwise not have access to because its credit rating is not sufficiently strong. A bank may also issue ABCP for balance sheet or funding reasons. ABCP trades, however, exactly as conventional CP. The administration and legal treatment is more onerous, however, because of the need to establish the CP trust structure and issuing SPV. The servicing of an ABCP programme follows that of conventional CP and is carried out by the same entities, such as the ‘Trust’ arms of banks such as Deutsche Bank and Bank of New York Mellon.

Example 2.5 (see p. 46) details a hypothetical ABCP issue and typical structure.

Basic characteristics

Asset-backed CP programmes are invariably issued out of specially incorporated legal entities (the SPV, sometimes called the SPC for special purpose corporation), which in the money markets are known as conduits. They are typically established by commerical banks and finance companies to enable them to access Libor-based funding, at close to Libor, and to obtain regulatory capital relief. This can be done for the bank or a customer.

An ABCP conduit has the following features:

- it is a bankruptcy-remote legal entity that issues commercial paper to finance a purchase of assets from a seller of assets;

- the interest on the CP issued by the conduit, and its principal on maturity, will be paid out of the receipts on the assets purchased by the conduit;

- conduits have also been set up to exploit credit arbitrage opportunities, such as raising finance at Libor to invest in high-quality assets such as investment-grade-rated structured finance securities that pay above Libor.

The assets that can be funded via a conduit programme are many and varied; to date they have included:

- trade receivables and equipment lease receivables;

- credit card receivables;

- auto loans and leases;

- corporate loans; franchise loans, mortgage loans;

- real estate leases;

- future (expected) cashflows.

Conduits are classified into a ‘programme type’, which refers to the makeup of the underlying asset portfolio. This can be single-seller or multi-seller, which indicates how many institutions or entities are selling assets to the conduit. They are also designated as funding or securities credit arbitrage vehicles.

A special class of conduit known as a structured investment vehicle (SIV, sometimes called a special investment vehicle) was introduced that issued both CP and medium-term notes (MTNs), used to fund the purchase of longer dated assets such as ABS and CDO securities. These were described as ‘credit arbitrage vehicles’ but were as much funding arbitrage vehicles. They were the first casualties of the 2007–2008 financial crisis and were either wound up or consolidated by their parent banks. The vehicles are now extinct and as a concept the SIV has been debunked.

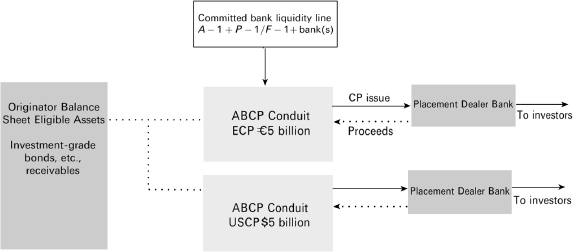

Figure 2.7 illustrates a typical ABCP structure issuing to the USCP and ECP markets.

Figure 2.7 Single-seller conduit.

Example 2.5 Illustration of ABCP structure

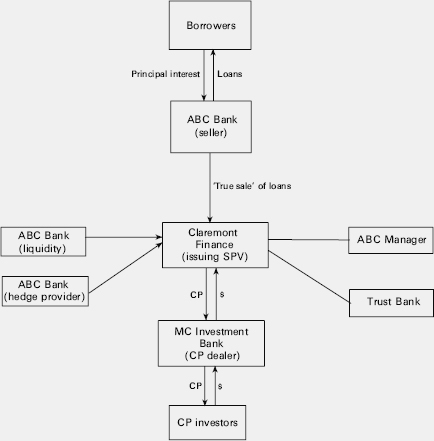

In Figure 2.8 we illustrate a hypothetical example of securitization of bank loans in an ABCP structure. The loans have been made by ABC Bank plc and are secured on borrowers’ specified assets. They are denominated in sterling. These might be a lien on property, cashflows of the borrowers’ business or other assets. The bank makes a ‘true sale’ of the loans to a special purpose vehicle, named Claremont Finance. This has the effect of removing the loans from its balance sheet and also protecting them in the event of bankruptcy or liquidation of ABC Bank. The SPV raises finance by issuing commercial paper, via its appointed CP dealer(s), which is the Treasury desk of MC Investment Bank. The paper is rated A-1/P-1 by the rating agencies and is issued in US dollars. The

Figure 2.8 ‘Claremont Finance’ ABCP structure.

liability of the CP is met by the cashflow from the original ABC Bank loans.

ABC Manager is the SPV manager for Claremont Finance, a subsidiary of ABC Bank. Liquidity for Claremont Finance is provided by ABC Bank, who also act as the hedge provider. The hedge is effected by means of a swap agreement between Claremont and ABC Bank; in fact, ABC will fix a currency swap with a swap bank counterparty, who is most likely to be the swap desk of MC Investment Bank. The trustee for the transaction is Trust Bank Limited, who act as security trustee and represent the investors in the event of default.

The other terms of the structure are as follows:

| Programme facility limit | US$500 million |

| Facility term | The facility is available on an uncommitted basis renewable annually by the agreement of the SPV manager and the security trustee. It has a final termination date five years from first issue. |

| Tenor of paper | Seven days to 270 days. |

| Pre-payment guarantee | In the event of pre-payment of a loan, the seller will provide Claremont Finance with a guaranteed rate of interest for the relevant interest period. |

| Hedge agreement | Claremont Finance will enter into currency and interest rate swaps with the hedge provider to hedge any interest rate or currency risk that arises. |

| Events of default | In the event of default the issuance programme will cease and in certain events will lead Claremont Finance to pay loan collections into a segregated specific collection account. Events of default can include non-payment by Claremont Finance under the transaction documentation, insolvency or ranking of charge (where the charge ceases to be a first-ranking charge over the assets of Claremont Finance). |

| Loans guarantee: | Loans purchased by Claremont Finance will meet a range of eligibility criteria, specified in the transaction-offering circular. These criteria will include requirements on currency of the loans, their term to maturity, confirmation that they can be assigned, that they are not in arrears, and so on. |

REPO

The term repo is used to cover one of two different transactions, the classic repo and the sell/buyback, and sometimes is spoken of in the same context as a similar instrument, the stock loan. A fourth instrument is also economically similar in some respects to a repo, known as the total return swap, which is now commonly encountered as part of the market in credit derivatives. However, although these transactions differ in terms of their mechanics, legal documentation and accounting treatment, the economic effect of each of them is very similar. The structure of any particular market and the motivations of particular counterparties will determine which transaction is entered into; there is also some crossover between markets and participants.

Market participants enter into classic repo because they wish to invest cash, for which the transaction is deemed to be cash-driven, or because they wish to borrow a certain stock, for which purpose the trade is stock-driven. A sell/buyback, which is sometimes referred to as a buy–sell, is entered into for similar reasons but the trade itself operates under different mechanics and documentation.6 A stock loan is just that, a borrowing of stock against a fee. Long-term holders of stock will therefore enter into stock loans simply to enhance their portfolio returns. We will look at the motivations behind the total return swap in a later chapter.

Note that during the interbank liquidity crisis from September 2008 to well into 2009, when unsecured inter-bank markets dried up, repo was the only funding mechanism still available to many banks.

Definition

A repo agreement is a transaction in which one party sells securities to another, and at the same time and as part of the same transaction commits to repurchase identical securities on a specified date at a specified price. The seller delivers securities and receives cash from the buyer. The cash is supplied at a predetermined rate – the repo rate – that remains constant during the term of the trade. On maturity the original seller receives back collateral of equivalent type and quality, and returns the cash plus repo interest. One party to the repo requires either the cash or the securities and provides collateral to the other party, as well as some form of compensation for the temporary use of the desired asset. Although legal title to the securities is transferred, the seller retains both the economic benefits and the market risk of owning them. This means that the ‘seller’ will suffer if the market value of the collateral drops during the term of the repo, as she still retains beneficial ownership of the collateral. The ‘buyer’ in a repo is not affected in P&L account terms if the value of the collateral drops, although there are other concerns for the buyer if this happens.

We have given here the legal definition of repo. However, the purpose of the transaction as we have described above is to borrow or lend cash, which is why we have used inverted commas when referring to sellers and buyers. The ‘seller’ of stock is really interested in borrowing cash, on which (s)he will pay interest at a specified interest rate. The ‘buyer’ requires security or collateral against the loan he has advanced, and/or the specific security to borrow for a period of time. The first and most important thing to state is that repo is a secured loan of cash, and would be categorized as a money market yield instrument.7

The classic repo

The classic repo is the instrument encountered in the US, UK and other markets. In a classic repo one party will enter into a contract to sell securities, simultaneously agreeing to purchase them back at a specified future date and price. The securities can be bonds or equities but can also be money market instruments, such as T-bills. The buyer of the securities is handing over cash, which on the termination of the trade will be returned to him, and on which he will receive interest.

The seller in a classic repo is selling or offering stock, and therefore receiving cash, whereas the buyer is buying or bidding for stock, and consequently paying cash. So, if the 1-week repo interest rate is quoted by a market-making bank as ![]() , this means that the market-maker will bid for stock – that is, lend the cash – at 5.50% and offers stock or pays interest on cash at 5.25%.

, this means that the market-maker will bid for stock – that is, lend the cash – at 5.50% and offers stock or pays interest on cash at 5.25%.

Illustration of classic repo

There will be two parties to a repo trade, let us say Bank A (the seller of securities) and Bank B (the buyer of securities). On the trade date the two banks enter into an agreement whereby on a set date – the value or settlement date – Bank A will sell to Bank B a nominal amount of securities in exchange for cash.8 The price received for the securities is the market value of the stock on the value date. The agreement also demands that on the termination date Bank B will sell identical stock back to Bank A at the previously agreed price, and, consequently, Bank B will have its cash returned with interest at the agreed repo rate.

In essence, a repo agreement is a secured loan (or collateralized loan) in which the repo rate reflects the interest charged.

On the value date, stock and cash change hands. This is known as the start date, first leg or opening leg, while the termination date is known as the second leg or closing leg. When the cash is returned to Bank B, it is accompanied by the interest charged on the cash during the term of the trade. This interest is calculated at a specified rate known as the repo rate. It is important to remember that, although in legal terms the stock is initially ‘sold’ to Bank B, the economic effects of ownership are retained with Bank A. This means that if the stock falls in price it is Bank A that will suffer a capital loss. Similarly, if the stock involved is a bond and there is a coupon payment during the term of trade, this coupon is to the benefit of Bank A and, although Bank B will have received it on the coupon date, it must be handed over on the same day or immediately after to Bank A. This reflects the fact that, although legal title to the collateral passes to the repo buyer, the economic costs and benefits of the collateral remain with the seller.

A classic repo transaction is subject to a legal contract signed in advance by both parties. A standard document will suffice; it is not necessary to sign a legal agreement prior to each transaction.

Note that, although we have called the two parties in this case ‘Bank A’ and ‘Bank B’, it is not only banks that get involved in repo transactions – we have used these terms for the purposes of illustration only.

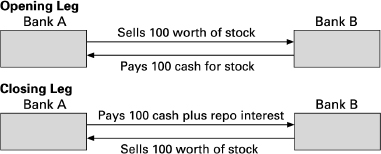

The basic mechanism is illustrated in Figure 2.9.

Figure 2.9 Classic repo transaction.

A seller in a repo transaction is entering into a repo, whereas a buyer is entering into a reverse repo. In Figure 2.9 the repo counterparty is Bank A, while Bank B is entering into a reverse repo. That is, a reverse repo is a purchase of securities that are sold back on termination. As is evident from Figure 2.9, every repo is a reverse repo, and the name given is dependent on from whose viewpoint one is looking at the transaction.9

Examples of classic repo

The basic principle is illustrated with the following example. This considers a specific repo – that is, one in which the collateral supplied is specified as a particular stock – as opposed to a general collateral (GC) trade in which a basket of collateral can be supplied, of any particular issue, as long as it is of the required type and credit quality.

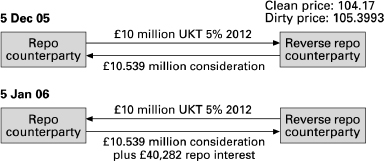

We first consider a classic repo in the UK gilt market between two market counterparties, in the 5.75% Treasury 2012 gilt stock as at 2 December 2005. The terms of the trade are given in Table 2.2 and the trade is illustrated in Figure 2.10.

Figure 2.10 Classic repo trade.

Table 2.2 Terms of a classic repo trade.

| Trade date | 2 December 2005 |

| Value date | 5 December 2005 |

| Repo term | 1 month |

| Termination date | 5 January 2006 |

| Collateral (stock) | UKT 5% 2012 |

| Nominal amount | 10,000,000 |

| Price | 104.17 |

| Accrued interest (89 days) | 1.229,281,8 |

| Dirty price | 105.3993 |

| Haircut | 0% |

| Settlement proceeds (wired amount) | 10,539,928.18 |

| Repo rate | 4.50% |

| Repo interest | 40,282.74 |

| Termination proceeds | 10,580,210.92 |

The repo counterparty delivers to the reverse repo counterparty 10 million nominal of the stock, and in return receives the purchase proceeds. In this example no margin has been taken, so the start proceeds are equal to the market value of the stock which is 10,539,928. It is common for a rounded sum to be transferred on the opening leg. The repo interest is 4.50%, so the repo interest charged for the trade is:

![]()

or 40,282.74. The sterling market day-count basis is actual/365, so the repo interest is based on a 7-day repo rate of 4.50%. Repo rates are agreed at the time of the trade and are quoted, like all interest rates, on an annualized basis. The settlement price (dirty price) is used because it is the market value of the bonds on the particular trade date and therefore indicates the cash value of the gilts. By doing this, the cash investor minimizes credit exposure by equating the value of the cash and the collateral.

On termination the repo counterparty receives back its stock, for which it hands over the original proceeds plus the repo interest calculated above.

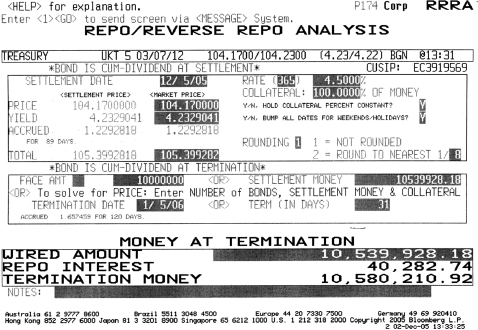

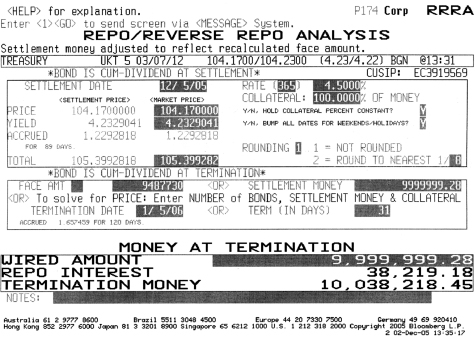

Market participants who are familiar with the Bloomberg LP trading system will use screen RRRA for a classic repo transaction. For this example the relevant screen entries are shown at Figure 2.11. This screen is used in conjunction with a specific stock, so in this case it would be called up by entering:

Figure 2.11 Bloomberg screen RRRA for classic repo.

© Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

![]()

where ‘UKT’ is the ticker for UK gilts. Note that the date format for Bloomberg screens is mm/dd/yy. The screen inputs are relatively self-explanatory, with the user entering the terms of the trade that are detailed in Table 2.2. There is also a field for calculating margin, labelled ‘collateral’ on the screen. As no margin is involved in this example, it is left at its default value of 100.00%. The bottom of the screen shows the opening leg cash proceeds or ‘wired amount’, the repo interest and the termination proceeds.

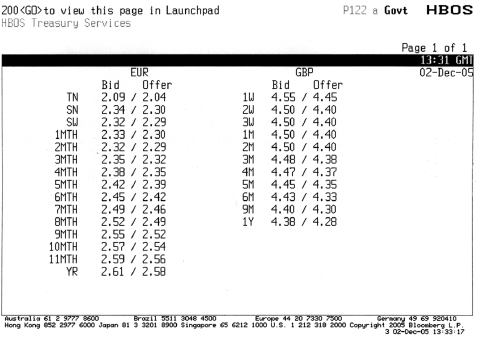

The repo rate for the trade is the 1-month rate of 4.50%, as shown in Figure 2.12, which is the HBOS repo rates screen as at 2 December 2005.10

Figure 2.12 HBOS repo rates screen as at 2 December 2005.

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

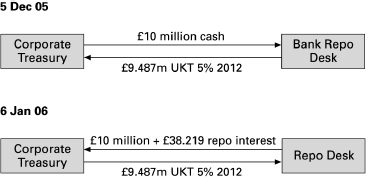

What if a counterparty is interested in investing 10 million against gilt collateral? Let us assume that a corporate treasury function with surplus cash wishes to invest this amount in repo for a 1-week term. It invests this cash with a bank that deals in gilt repo. We can use Bloomberg screen RRRA to calculate the nominal amount of collateral required. Figure 2.13 shows the screen for this trade, again against the 5.75% Treasury 2012 stock as collateral. We see from Figure 2.13 that the terms of the trade are identical to those in Table 2.2, including the tenor and the repo rate; however, the opening leg wired amount is entered as 10 million, which is the cash being invested. Therefore, the nominal value of the gilt collateral required will be different, as we now require a market value of this stock of 10 million. From the screen we see that this is 9,487,773.00. The cash amount is different from the example at Figure 2.14, so of course the repo interest charged is different and is 38,219.18 for the 1-month term.

Figure 2.13 Bloomberg screen for classic repo trade described on this page.

© Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 2.14 Corporate treasury classic repo, as illustrated in Figure 2.13.

The diagram at Figure 2.14 illustrates the transaction.

The sell/buyback

In addition to classic repo, there exists sell/buyback. A sell/buyback is defined as an outright sale of a bond on the value date, and an outright repurchase of that bond for value on a forward date. The cashflows therefore become a sale of the bond at the spot price, followed by repurchase of the bond at the forward price. The forward price calculated includes interest on the repo, and is therefore a different price to the spot price. That is, repo interest is realized as the difference between the spot price and forward price of the collateral at the start and termination of the trade. The sell/buyback is entered into for the same considerations as a classic repo, but was developed initially in markets where there is no legal agreement to cover repo transactions, and where the settlement and IT systems of individual counterparties were not equipped to deal with repo. Over time sell/buybacks have become the convention in certain markets, most notably Italy, and so the mechanism is still retained. In many markets, therefore, sell/buybacks are not covered by a legal agreement, although the standard legal agreement used in classic repo now includes a section that describes them.11

A sell/buyback is a spot sale and forward repurchase of bonds transacted simultaneously, and the repo rate is not explicit, but is implied in the forward price. Any coupon payments during the term are paid to the seller; however, this is done through incorporation into the forward price, so the seller will not receive it immediately, but on termination. This is a disadvantage when compared with classic repo. However, there will be compensation payable if a coupon is not handed over straight away, usually at the repo rate implied in the sell/buyback. As sell/buybacks are not subject to a legal agreement in most cases, in effect the seller has no legal right to any coupon, and there is no provision for marking to market and variation margin. This makes the sell/buyback a higher risk transaction when compared with classic repo, even more so in volatile markets.

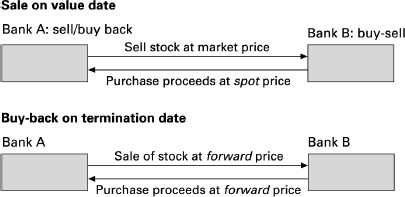

A general diagram for the sell/buyback is given at Figure 2.15.

Figure 2.15 Sell/buy-back transaction.

Examples of sell/buyback

We use the same terms of trade given in the previous section, but this time the trade is a sell/buyback.12 In a sell/buyback we require the forward price on termination, and the difference between the spot and forward price incorporates the effects of repo interest. It is important to note that this forward price has nothing to do with the actual market price of the collateral at the time of forward trade. It is simply a way of allowing for the repo interest that is the key factor in the trade. Thus, in sell/buyback the repo rate is not explicit (although it is the key consideration in the trade), rather it is implicit in the forward price.

In this example, one counterparty sells 10 million nominal of the UKT 5% 2012 at the spot price of 104.17, this being the market price of the bond at the time. The consideration for this trade is the market value of the stock, which is 10,539,928.18 as before. Repo interest is calculated on this amount at the rate of 4.50% for 1 month, and from this the termination proceeds are calculated. The termination proceeds are divided by the nominal amount of stock to obtain the forward dirty price of the bond on the termination date. For various reasons – the main one being that settlement systems deal in clean prices – we require the forward clean price, which is obtained by subtracting the accrued interest on the bond on the termination date from the forward dirty price. At the start of the trade, the 5% 2012 had 89 days’ accrued interest, therefore on termination this figure will be or 120 days.

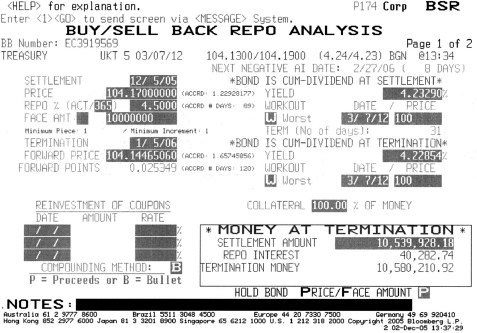

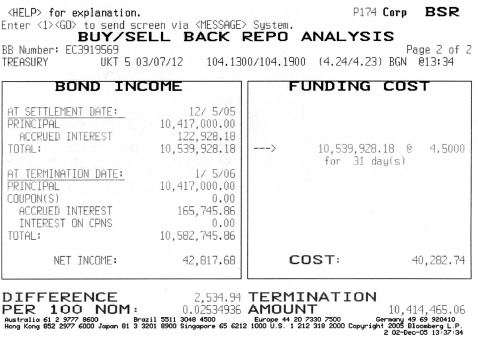

Bloomberg users access a different screen for sell/buybacks, which is BSR. This is shown at Figure 2.16. Entering in the terms of the trade, we see from Figure 2.16 that the forward price is 104.144. However, the fundamental element of this transaction is evident from the bottom part of the screen: the settlement amount (‘wired amount’), repo interest and termination amount are identical to the classic repo trade described earlier. This is not surprising; the sell/buyback is a loan of 10.539 million for 1 month at an interest rate of 4.50%. The mechanics of the trade do not impact on this key point.

Figure 2.16 Bloomberg screen BSR for sell/buyback trade in 5% 2012.

© Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Screen BSR on Bloomberg has a second page, which is shown at Figure 2.17. This screen summarizes the cash proceeds of the trade at start and termination. Note how repo interest is termed ‘funding cost’. This is because the trade is deemed to have been entered into by a bond-trader who is funding his book. This will be considered later, but we can see from the screen details that during the 1 month of the trade the bond position has accrued interest of 165,745.00. This compares favourably with the repo funding cost of 122,928.18. The funding cost is therefore below the accrued interest gained on the bondholding, as shown in the screen.

Figure 2.17 Bloomberg screen BSR page 2 for sell/buyback trade in 5.75% 2009.

© 2009 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

If there is a coupon payment during a sell/buyback trade and it is not paid over to the seller until termination, a compensating amount is also payable on the coupon amount, usually at the trade’s repo rate. When calculating the forward price on a sell/buyback where a coupon will be paid during the trade, we must subtract the coupon amount from the forward price. Note also that sell/buybacks are not possible on an open basis, as no forward price can be calculated unless a termination date is known.

Repo collateral

The collateral in a repo trade is the security passed to the lender of cash by the borrower of cash. It is not always secondary to the transaction; in stock-driven transactions the requirement for specific collateral is the motivation behind the trade. However, in a classic repo or sell/buyback, the collateral is always the security handed over against cash.13 In a stock loan transaction, the collateral against stock lent can be either securities or cash. Collateral is used in repo to provide security against default by the cash borrower. Therefore, it is protection against counterparty risk or credit risk, the risk that the cash-borrowing counterparty defaults on the loan. A secured or collateralized loan is theoretically lower credit risk exposure for a cash lender compared with an unsecured loan.

The most commonly encountered collateral is government bonds, and the repo market in government bonds is the largest in the world. Other forms of collateral include Eurobonds, other forms of corporate and supranational debt, asset-backed bonds, mortgage-backed bonds, money market securities such as T-bills, and equities.

In any market where there is a defined class of collateral of identical credit quality, this is known as general collateral (GC). So, for example, in the UK gilt market a GC repo is one where any gilt will be acceptable as repo collateral. Another form of GC might be ‘AA-rated sterling Eurobonds’. In the US market the term stock collateral is sometimes used to refer to GC securities. In equity repo it is more problematic to define GC and by definition almost all trades are specifics; however, it is becoming more common for counterparties to specify any equity being acceptable if it is in an established index – for example, a FTSE 100 or a CAC 40 stock – and this is perhaps the equity market equivalent of GC. If a specific security is required in a reverse repo or as the other side of a sell/buyback, this is known as a specific or specific collateral. A specific stock that is in high demand in the market, such that the repo rate against it is significantly different from the GC rate, is known as a special.

Where a coupon payment is received on collateral during the term of a repo, it is to the benefit of the repo seller. Under the standard repo legal agreement, legal title to collateral is transferred to the buyer during the term of the repo, but it is accepted that the economic benefits remain with the seller. For this reason, coupon is returned to the seller. In classic repo (and in stock lending) the coupon is returned to the seller on the dividend date, or in some cases on the following date. In a sell/buyback the effect of the coupon is incorporated in the repurchase price. This includes interest on the coupon amount that is payable by the buyer during the period from the coupon date to the buyback date.

Legal treatment

Classic repo is carried out under a legal agreement that defines the transaction as a full transfer of the title to the stock. The standard legal agreement is the PSA/ISMA GRMA, which we review in the sister book in this series, An Introduction to Repo Markets. It is now possible to trade sell/buybacks under this agreement as well. This agreement was based on the PSA standard legal agreement used in the US domestic market, and was compiled because certain financial institutions were not allowed to legally borrow or lend securities. By transacting repo under the PSA agreement, these institutions were defined as legally buying and selling securities rather than borrowing or lending them.

Margin

To reduce the level of risk exposure in a repo transaction, it is common for the lender of cash to ask for a margin, which is where the market value of collateral is higher than the cash value of cash lent out in the repo. This is a form of protection, should the cash-borrowing counterparty default on the loan. Another term for margin is overcollateralization or a haircut. There are two types of margin: initial margin taken at the start of the trade and variation margin which is called if required during the term of the trade.

Initial margin

The cash proceeds in a repo are typically no more than the market value of the collateral. This minimizes credit exposure by equating the value of the cash to that of the collateral. The market value of the collateral is calculated at its dirty price, not clean price – that is, including accrued interest. This is referred to as accrual pricing. To calculate the accrued interest on the (bond) collateral we require the day-count basis for the particular bond.

The start proceeds of a repo can be less than the market value of the collateral by an agreed amount or percentage. This is known as the initial margin or haircut. The initial margin protects the buyer against

- a sudden fall in the market value of the collateral;

- illiquidity of collateral;

- other sources of volatility of value (e.g., approaching maturity);

- counterparty risk.

The margin level of repo varies from 0%–2% for collateral such as UK gilts to 5% for cross-currency and equity repo, to 10%–35% for emerging market debt repo.

In both classic repo and sell/buyback, any initial margin is given to the supplier of cash in the transaction. This remains the case in the case of specific repo. For initial margin the market value of the bond collateral is reduced (or given a haircut) by the percentage of the initial margin and the nominal value determined from this reduced amount. In a stock loan transaction the lender of stock will ask for margin.

There are two methods for calculating margin; for a 2% margin this could be one of the following:

- the dirty price of the bonds × 0.98;

- the dirty price of the bonds ÷ 1.02.

The two methods do not give the same value! The RRRA repo page on Bloomberg uses the second method for its calculations, and this method is turning into something of a convention.

For a 2% margin level the PSA/ISMA GRMA defines a ‘margin ratio’ as:

![]()

The size of margin required in any particular transaction is a function of the following:

- the credit quality of the counterparty supplying the collateral – for example, a central bank counterparty, interbank counterparty and corporate will all suggest different margin levels;

- the term of the repo – an overnight repo is inherently lower risk than a 1-year repo;

- the duration (price volatility) of the collateral – for example, a T-bill against the long bond;

- the existence or absence of a legal agreement – a repo traded under a standard agreement is considered lower risk.

However, in the final analysis, margin is required to guard against market risk, the risk that the value of collateral will drop during the course of the repo. Therefore, the margin call must reflect the risks prevalent in the market at the time; extremely volatile market conditions may call for large increases in initial margin.

Variation margin

The market value of collateral is maintained through the use of variation margin. So, if the market value of collateral falls, the buyer calls for extra cash or collateral. If the market value of collateral rises, the seller calls for extra cash or collateral. In order to reduce the administrative burden, margin calls can be limited to changes in the market value of collateral in excess of an agreed amount or percentage, which is called a margin maintenance limit.

The standard market documentation that exists for the three structures covered so far includes clauses that allow parties to a transaction to call for variation margin during the term of a repo. This can be in the form of extra collateral, if the value of collateral has dropped in relation to the asset exchanged, or a return of collateral, if the value has risen. If the cash-borrowing counterparty is unable to supply more collateral where required, he will have to return a portion of the cash loan. Both parties have an interest in making and meeting margin calls, although there is no obligation. The level at which variation margin is triggered is often agreed beforehand in the legal agreement put in place between individual counterparties. Although primarily viewed as an instrument used by the supplier of cash against a fall in the value of the collateral, variation margin can of course also be called by the repo seller if the value of the collateral has risen.

CURRENCIES USING MONEY MARKET YEAR BASE OF 365 DAYS

- Sterling;

- Hong Kong dollar;

- Malaysian ringgit;

- Singapore dollar;

- South African rand;

- Taiwan dollar;

- Thai baht.

In addition, the domestic markets, but not the international markets, of the following currencies also use a 365-day base:

- Australian dollar;

- Canadian dollar;

- Japanese yen;

- New Zealand dollar.

To convert an interest rate quoted on a 365-day basis to one quoted on a 360-day basis use the expressions given at (2.15):

1 A small number of CDs are non-negotiable.

2 With thanks to Del Boy during the time he was at Tradition for pointing this out after I’d just bought a sizeable chunk of Japanese bank CDs circa 1993.

3 A banker’s acceptance created to finance such a transaction is known as a third-party acceptance.

4 This is the Securities Act of 1933. Registration is with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

5 Source: BIS.

6 We shall use the term ‘sell/buyback’ throughout this book. A repo is still a repo whether it is cash-driven or stock-driven, and one person’s stock-driven trade may well be another’s cash-driven one.

7 That is, a money market instrument quoted on a yield instrument, similar to a bank deposit or a CD. The other class of money market products are discount instruments such as T-bills or CP.

8 The two terms are not necessarily synonymous. The value date in a trade is the date on which the transaction acquires value – for example, the date from which accrued interest is calculated. As such it may fall on a non-business day – such as a weekend or public holiday. The settlement date is the day on which the transaction settles or clears, and so can only fall on a working day.

9 Note that the guidelines to the syllabus for the Chartered Financial Analyst examination, which is set by the Association for Investment Management and Research, defines repo and reverse repo slightly differently. Essentially, a ‘repo’ is conducted by a bank counterparty and a ‘reverse repo’ is conducted by an investment counterparty or non-financial counterparty. Another definition states that a ‘repo’ is any trade where the bank counterparty is offering stock (borrowing cash) and a ‘reverse repo’ is any trade where the non-bank counterparty is borrowing cash. The author does not make this distinction; by definition every repo is a ‘reverse repo’ for the other side.

10 The author used to deal with Leeds Permanent Building Society, whose rates screen he made use of in the early 1990s. This became Halifax plc and then HBOS. Sadly, these entities are no longer with us, but the HBOS screen has been retained for nostalgic reasons.

11 This is the PSA/ISMA Global Master Repurchase Agreement, which is reviewed in the author’s book Introduction to Repo Markets, 3rd edition, part of this series by John Wiley & Sons.

12 The Bank of England discourages sell/buybacks in the gilt repo and it is unusual to observe them in this market. However, we use these terms of trade for comparison with the classic repo example given in the previous section.

13 So that even in a stock-driven reverse repo the collateral is the security handed over against the borrowing of cash by the repo seller.