CHAPTER 6

Workplace

The HR expertise domain of Workplace Knowledge counts toward 16 percent for both exams. This domain covers the essential HR knowledge needed for relating to the workplace. The following are the functional areas that fall within the Workplace Knowledge domain:

• Functional Area 11—HR in the Global Context

• Functional Area 12—Diversity and Inclusion

• Functional Area 13—Risk Management

• Functional Area 14—Corporate Social Responsibility

• Functional Area 15—U.S. Employment Law and Regulations

HR professionals are expected to know how to perform the following Body of Competency and Knowledge (BoCK) statements for the Workplace Knowledge domain:

• 01 Fostering a diverse and inclusive workforce

• 02 Managing organizational risks and threats to the safety and security of employees

• 03 Contributing to the well-being and betterment of the community

• 04 Complying with applicable laws and regulations

Functional Area 11—HR in the Global Context

Here is SHRM’s BoCK definition: “HR direction required to achieve organizational success and to create value for stakeholders.”1

Globalization is here. It has been coming for more than half a century. Now, technology has altered our lives and the way we interact so that world markets, world politics, and world education have all come to our personal cell phones. Employers, too, are now tapped into world suppliers, world customers, and world recruiting like never before in history. It is going to be increasingly difficult to locate an employer that doesn’t tap into the Internet resources available from these world sources.

Key Concepts

• Best practices for international assignments (e.g., approaches and trends, effective performance, health and safety, compensation adjustments, employee repatriation, socialization)

• Requirements for moving work (e.g., co-sourcing, near-shoring, off-shoring, on-shoring)

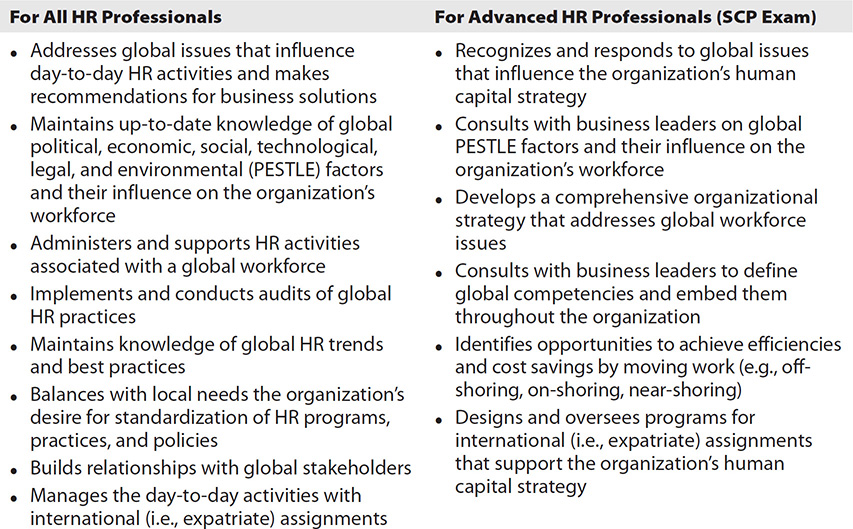

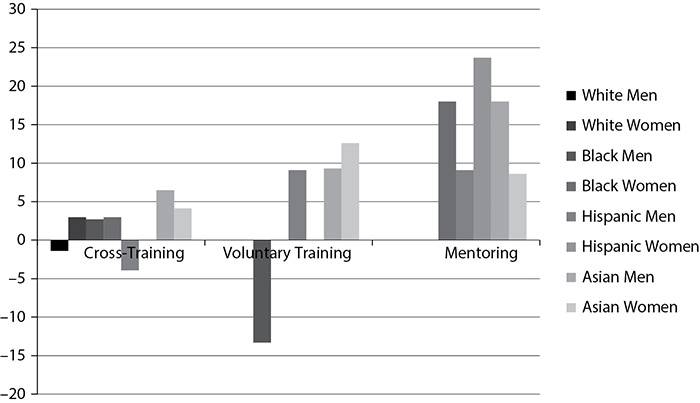

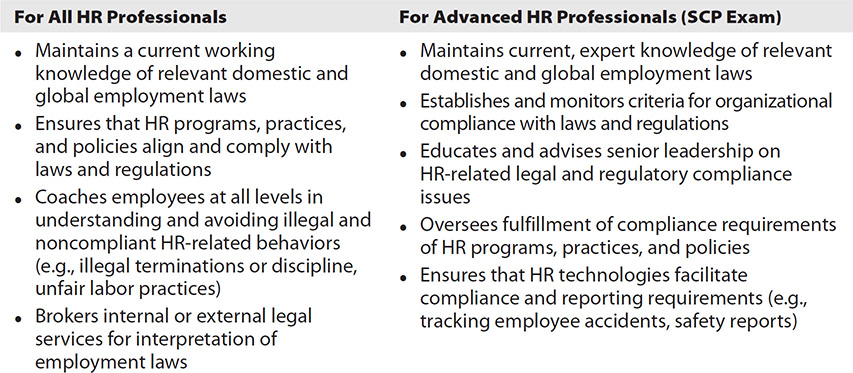

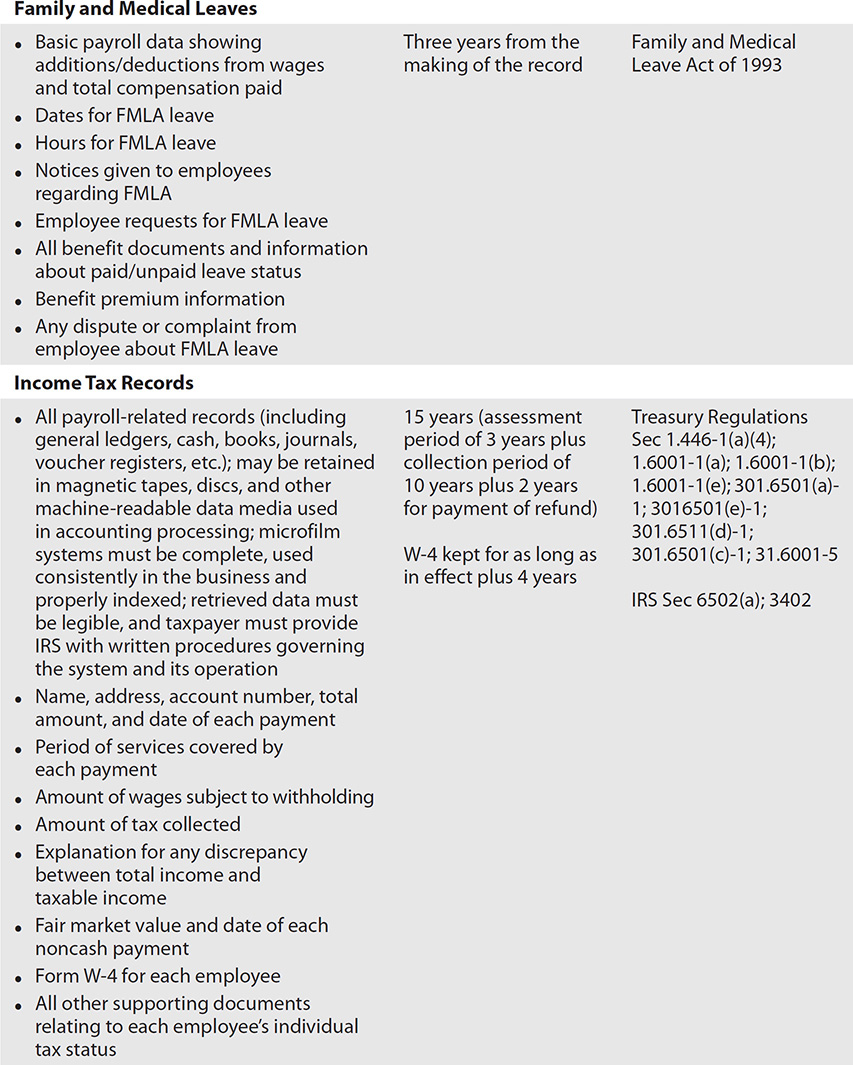

The following are the proficiency indicators that SHRM has identified as key concepts:

![]()

The Global Context

No longer are we just Americans, Mexicans, Canadians, or Swiss. Global interactions mean we must find ways to place our employer issues in a global context while still abiding by the cultural and legal requirements of each country in which we operate. Globalization is a larger version of the U.S. state differences and how they contribute to the American context.

Defining Globalization

Globalization is the trend of increasing interaction between people on a worldwide scale because of advances in transportation and communication technology.2 Business and governmental requirements are also contributing factors in the new definition of globalization. Overall, it represents a compression of the world and intensification of the consciousness of the world as a whole.

Forces Shaping Globalization

International economic influences (finance and development), environmental forces, political forces, global insecurity, and a refugee crisis, along with insecure investment trading markets (Dow Jones, Nasdaq, commodities markets), all contribute to shaping the thing we call globalization. Ultimately, these forces boil down to the shift from developed to emerging economies, a global recession and global warming, and hyper-connectivity.

Three Precepts of Global Force Interconnectedness Taking all of the forces into consideration, there are three precepts of global force interconnectedness that become apparent.

• PEST factors can be fully understood only as global impacts.

• Forces may be global, but impacts can be uniquely felt locally.

• We need to distinguish between large-scale forces and trends and more immediate events and “trendy” phenomena.

Globalization in the Twenty-First Century Thomas L. Friedman reminds us, we used to build our towns and factories along rivers because they provided access to neighbors and their ideas, power, mobility, and nourishment. “But the rivers you want to build on now are Amazon Web Services or Microsoft’s Azure—giant connectors that enable you, your business, or your nation to get access to all the computing power applications in the [worldwide Internet of Things], where you can tie into every flow in the world in which you want to participate.”3

HR professionals no longer have the luxury of thinking only about their own local, state, or federal interactive requirements. International requirements are always nearby in terms of off-shore manufacturing, importing rules and procedures, and exporting rules and procedures. Monetary impact comes from all parts of the earth. Workforce recruiting, talent management, and policy influences come from more countries as time goes by.

Some experts have pointed out that the workforce in emerging world economies is primarily young, while the workforce in developed countries is aging. The problems presented by each of those populations are quite different. HR professionals must be able to address both.

Shift from Developed to Emerging Economies

The long-term global economic power shift away from the established advanced economies is set to continue to 2050, as emerging market countries continue to boost their share of world GDP in the long run despite recent mixed performance in some of these economies.4

The Diaspora The World Encyclopedia suggests diaspora refers to any people or ethnic population forced or induced to leave its traditional homeland, as well as the dispersal of such people and the ensuing developments in their culture. It is especially used with reference to the Jewish population, who have lived most of their historical existence as a diasporan people.5

Demographic Dichotomy The workforce in emerging economies is becoming disproportionately young, while the workforce in developed economies is rapidly aging (parallel demographic shift).6

Reverse Innovation Innovations created for or by emerging-economy markets and then imported by developed-economy markets suggests that the “new” economies will have a greater influence over world economic events because they are selling their innovations to markets in developed countries.

Global Recession and Global Warming

Episodes of severe weather in the United States, such as the abundance of rainfall and then drought in California, are brandished as tangible evidence of the future costs of current climate trends. A study by Hsiang et al. (published in the journal Science)7 collected national data documenting the responses in six economic sectors to short-term weather fluctuations. This data was integrated with probabilistic distributions from a set of global climate models and used to estimate future costs during the remainder of this century across a range of scenarios. In terms of overall effects on the gross domestic product, the authors predict negative impacts in the southern United States and positive impacts in some parts of the Pacific Northwest and New England.

Hyper-connectivity

Hyper-connectivity is a state of unified communications (UC) in which the traffic-handling capacity and bandwidth of a network always exceed the demand. The number of communication pathways and nodes is much greater than the number of subscribers.8 This is evidenced by the increasing digital interconnection of people and things around the clock from anywhere.

Achieving a Public-Private Balance The government fiscal balance is one of three major financial sectorial balances in the national economy, the others being the foreign financial sector and the private financial sector. The sum of the surpluses or deficits across these three sectors must be zero by definition. Hence, a foreign financial surplus (or capital surplus) exists because capital is imported (net) to fund the trade deficit. Further, there is a private sector financial surplus due to household savings exceeding business investment. By definition, there must therefore exist a government budget deficit so all three net to zero. The government sector includes federal, state, and local.9

Measurability If you can’t measure it, why spend time working on it? Each of the issues we are discussing in this functional area can be measured if you take the time to think about them.

Moving Work

Globalization more than anything has resulted in employers finding ways to do their work better, cheaper, and faster by looking outside traditional local recruiting sources. Here are some of the influences we see today:

• Outsourcing The transfer of some work to organizations outside the employer’s payroll. The vendor may be across the street or across the country.

• Off-shoring The transfer of some work to sources outside the United States.

• On-shoring (home-shoring) The relocation of business processes or production to a lower-cost location inside the same country as the business.

• Near-shoring Contracting part of the business processes or production to an external company located in a country that is relatively close. For the United States, that could mean Mexico or Canada.

HR professionals play a critical role in supporting the decision-making effort involved in moving work from one location to another. In performing due diligence, HR professionals should perform research on each of the following:

• Talent pool Languages spoken, cultural differences.

• Sociopolitical environment Governmental regulations, the expense involved in meeting them. Quality of life and ethical environment can create certain expenses.

• Risk levels IT security, political and labor conflicts, natural disasters, and security for individuals and property.

• Cost and quality Wage structure, tax structure, communication facilities, Internet access.

Defining the Global Organization

A global corporation is a business that operates in two or more countries. It also goes by the name multinational company.

![]()

Defining the Role of Global HR

Global businesses should have a global HR function. At the same time, to compete successfully in diverse markets, companies should recruit, train, and manage people locally—reflecting local culture, local labor markets, and the needs of diverse local business units.10

• Business and talent strategies should be global in scale and local in implementation. Effective programs recruit, train, and develop people locally.

• Global HR and talent management is the second most urgent and important trend for large companies around the world (those with 10,000 or more employees), according to Deloitte Insights’ global survey.10

• Companies face the challenge of developing an integrated global HR and talent operating model that allows for customizable local implementation, enabling them to capitalize on rapid business growth in emerging economies, tap into local skills, and optimize local talent strategies.

Creating a Global Strategy

As firms expand into countries around the world, more and more are deciding that they need to create an overarching, global human resources strategy. This is because HR leaders must adhere to local laws but still meet the needs of regional staff all while maintaining an across-the-board strategy.11

The Strategic Attraction of Globalization

Current attitudes toward globalization have resulted in new thinking called guarded globalization. Governments of developing nations have become wary of opening more industries to multinational companies and are zealously protecting local interests. They choose the countries or regions with which they want to do business, pick the sectors in which they will allow capital investment, and select the local, often state-owned, companies they want to promote. That’s a different flavor of globalization: slow-moving, selective, and with a heavy dash of nationalism and regionalism.12

“Push” Factors These are examples of “push” factors influencing global organizations:13

• Saturation of domestic demand and need for new markets The market for a number of products tends to saturate or decline in advanced countries. This often happens when the market potential has been almost fully tapped. For example, the fall in the birth rate implies contraction of a market for several baby products. Businesses undertake international operations to expand sales, acquire resources from foreign countries, or diversify their activities to discover the lucrative opportunities in other countries.

• Shortfalls in natural resources and talent supply When natural resources begin dwindling in developed countries, it seems reasonable for organizations to look to other countries for their raw materials. Creating a physical presence where the resources are located can help reduce the costs of acquisition. Moving to locations where talent can be found is a common solution for dwindling talent supplies in the home country.

• Trade agreements Global expansion is driven by domestic competition from foreign competitors.

• Technological revolution Revolution is a right word that can best describe the pace at which technology has changed in the recent past and is continuing to change. Significant developments are being witnessed in communication, transportation, and information processing, including the emergence of the Internet and the World Wide Web.

• Globalized supply chain Moving production facilities closer to supplier locations can help reduce costs involved in moving raw materials before processing.

• Domestic recession Domestic recession often provokes companies to explore foreign markets. One of the factors that prompted Hindustan Machine Ltd. (HMT) to take up exports seriously was the recession in the home market in the late 1960s.

• Increased cost pressures and competition as driving force Competition may become a driving force behind internationalization. There might be intense competition in the home market but little in certain foreign countries. A protected market does not normally motivate companies to seek business outside the home market.

• Government policies and regulations Government policies and regulations may also motivate internationalization. There are both positive and negative factors that could cause internationalization. Many governments offer a number of incentives and other positive support to domestic companies to export and to invest in foreign locations. Tax subsidies or even tax forgiveness can be a strong magnet for international business moves.

• Improving the image of companies International business has certain spin-offs too. It may help the company improve its domestic business; international business helps to improve the image of the company. There may be the “white skin” advantage associated with exporting: when domestic consumers get to know that the company is selling a significant portion of the production abroad, they will be more inclined to buy from such a company.

• Strategic vision The systematic and growing internationalization of many companies is essentially part of their business policy or strategic management. The stimulus for internationalization comes from the urge to grow, the need to become more competitive, the need to diversify, and the need to gain strategic advantages of internationalization.

“Pull” Factors Here are some factors that make “foreign” markets attractive:14

• Government policies When policies encourage foreign investment, domestic organizations may find it financially beneficial to locate in foreign markets. There may be tax advantages gained by expanding into foreign locations.

• Strategic control Many multinational companies (MNCs) are locating their subsidiaries in low-wage and low-cost countries to take advantage of low-cost production. When it becomes easier to control things such as brand image by having a subsidiary in a foreign country, organizations can be seen taking that leap.

• Taking advantage of growth opportunities MNCs are getting increasingly interested in several developing countries as the income and population are rapidly rising in these countries. Foreign markets can flourish in both developed and developing countries.

• Declining trade and investment barriers Declining trade and investment barriers have vastly contributed to globalization. Business across the globe has grown considerably in a free trade regime. Goods, services, capital, and technology all benefit significantly moving across nations.

Regional trading blocs are adding to the pace of globalization. WTO, EU, NAFTA, MERCOSUR, and FTAA are major alliances among countries. Trading blocs seek to promote international business by removing trade and investment barriers. Integration among countries results in efficient allocation of resources throughout the trading area, promoting growth of some business and decline of others, development of new technologies and products, and elimination of old technologies.

Strategic Approaches to Globalization

A firm using a global strategy sacrifices responsiveness to local requirements within each of its markets in favor of emphasizing efficiency. This strategy is a complete opposite of a multidomestic strategy. Some minor modifications to products and services may be made in various markets, but a global strategy stresses the need to gain economies of scale by offering essentially the same products or services in each market.15

These are some approaches to strategic globalization:

• Creating a new organization in the foreign country

• Acquiring a subsidiary in the foreign country perhaps through merger or acquisition

• Creating a new partnership

• Outsourcing all or at least some of the production tasks to a supplier in a new work location

• Adding capacity to existing domestic locations by offshoring

Global Integration (GI) vs. Local Responsiveness (LR) Adjustments for consumer preference is one strategy for the globalization of product marketing. H. J. Heinz adapts its products to match local preferences. Because some Indians will not eat garlic and onion, for example, Heinz offers them a version of its signature ketchup that does not include these two ingredients. On the other hand, such alterations are not needed in products hidden from consumer view. Intel’s processing chips are an example. There is no need to modify the chips for various international cultures. The chips will work the same across all cultures. Such is a benefit of global integration.

Achieving Global Integration Global integration means the decisions are made from a global perspective, and in some cases the meganational firm operates as if the world were one market.

Achieving Local Responsiveness Local responsiveness is achieved by delegating most of the decision-making responsibility to local units and by appointing a local manager to the top management teams of subsidiaries.

Global integration vs. Local Responsiveness Examples BASF is a German-based corporation that is one of the largest chemical production companies in the world. It has more than 330 plants producing a host of chemicals for nearly all industries in the world that use chemicals. Its chemicals are standard, regardless of the country where they will be used. That is global integration.

Beverage companies produce various brands and flavors in local markets worldwide. Coca-Cola offers Georgia Coffee in Japan, Café Zu in Thailand, Inca Cola in Peru, and the Burn energy drink in France. Adjustments for local taste are examples of local responsiveness.

Global-Local Models There is a range of strategic choices available within the global-local concept.

Upstream and Downstream Strategies A simple metaphor like “upstream and downstream” can help you identify the strategies that you can apply.

• Upstream Decisions are made at headquarters and apply to strategies for focusing on the standardization of processes and integration of resources. That can be a strategy for workforce alignment, organizational development, and sharing knowledge and experience across internal organization boundaries.

• Downstream Decisions are made at the local level and target adapting strategic goals to local realities. That can be a strategy for agreements with local work groups, adjustments to standard policies related to working conditions that reflect local requirements, and adjustments to operations based on local requirements.

Identity Alignment and Process Alignment As strategies, identify alignment and process alignment offer some possible benefits to multinational organizations.

• Identify alignment This is based on the diversity of people, products/services, and branding; differences among locations; and adjustment of brand identity and products/services based on local culture. Some downside risks are that localized offerings can dilute the brand or product/service image unless the corporate brand is well established, and local approaches can diffuse the core organizational identity. Think of McDonald’s hamburgers. In most markets around the world, beef burgers are acceptable. In India, however, religion prevents a large portion of the population from eating beef. In that local market, products with chicken and fish are much more widely accepted.

• Process alignment This is how well common internal functions can work across all locations. Are the same technologies used in all locations for accounting, HR, finance, legal? Are the same performance measurements used in all locations? Is a unified HR system used in all locations? This can be a problem when one organization acquires another. There is great inertia within each organization for continuing to use their own systems. Blending them or replacing them can be and is often problematic.

The FI-LR Matrix: Strategic Options For many years scholars have been studying the relationships between global integration and local responsiveness.16 The following table illustrates what they developed.

• International strategy All products/services, processes, and strategy at all levels are developed in the home country even though the organization may export products or services to other countries.

• Multidomestic strategy Headquarters has little influence over remote subsidiary units. They develop their own strategies and goals.

• Global strategy Headquarters develops and disseminates strategies, products, and services. All offerings are the same worldwide. Local entities can influence global image or products very little. Customizable elements are kept to a minimum.

• Transnational strategy Remote locations are chosen for their access to supplies, vendors, and local markets. Subsidiaries are permitted to make adaptations to global products for appeal to local markets. Knowledge and practices are shared among all units in the organization. HQ assumes responsibility for certain factors such as advertising and strategies.

Perimutter’s Headquarters Orientations Howard Perlmutter identified a way of classifying alternative management orientations, which is commonly referred as Perlmutter’s EPRG model. He states that businesses and their staff tend to operate in one of four ways.17

• Ethnocentric These people or companies believe that their home country is superior. When they look to new markets, they rely on what they know and seek similarities with their own country. Overseas subsidiaries or offices in international markets are seen as less able and less important than the head office. Typically, these companies make few adaptations to their products and undertake little research in the international markets.

• Polycentric Polycentric organizations or managers see each country as unique and consider that businesses are best run locally. Polycentric management means that the head office places little control on the activities in each market, and there is little attempt to make use of any good ideas or best practices from other markets.

• Regiocentric Regiocentric sees similarities and differences in a world region and designs strategies around this. Often there are major differences between countries in a region. For example, Norway and Spain are both in Europe but are very different in climate, culture, transport, retail distribution, and so on. Another example of a regiocentric management orientation occurs when a U.S. company focuses on countries included in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

• Geocentric Geocentric companies, as truly global players, view the world as a potential market and seek to serve this effectively. Geocentric management recognizes the similarities and differences between the home country and the international markets. It combines ethnocentric and polycentric views; in other words, it displays the “think global, act local” ideology.

Sourcing and Shoring

As a product of globalization, work is moved to the most advantageous location. That can bring off-shoring and outsourcing into play.

Off-shoring This is the practice of placing production or other elements of the organization in another country. Off-shoring is sometimes chosen because it offers lower costs, it offers production a closer location for raw materials, it offers better tax impact or other financial impact, or there are direct financial incentives, such as government-sponsored loans or cash payments. It can also take advantage of time zone differences, and work can be done on a project without interruption should the appropriate workforce be scattered around the globe.

Disadvantages of off-shoring can include a strong resistance from customers, whom even call the practice “unpatriotic.” Other problems that sometimes arise are language difficulties, cultural differences, high turnover rates, quality control issues, and educational degrees that do not offer reliable skills or talents.

On-shoring When business processes, product manufacturing, or other functions are contracted out to another organization within the home country, it is called on-shoring. Having home-country employees can often avoid the problems associated with off-shoring.

Near-Shoring The practice of contracting part of the organization’s business processes to a country that is close to the home country is known as near-shoring. A company in the United States selecting manufacturing subcontractors in Mexico for making its automobiles or washing machines is a good example. These arrangements are influenced to a great degree by trade agreements and social or economic stability.

Outsourcing Almost always outsourcing is evidenced by contracts with vendors in the home country other countries that can provide products or services more cheaply than can be offered at headquarters. A prime example is the use of call centers to support customer service and order processing.

HR’s Role in Globalization

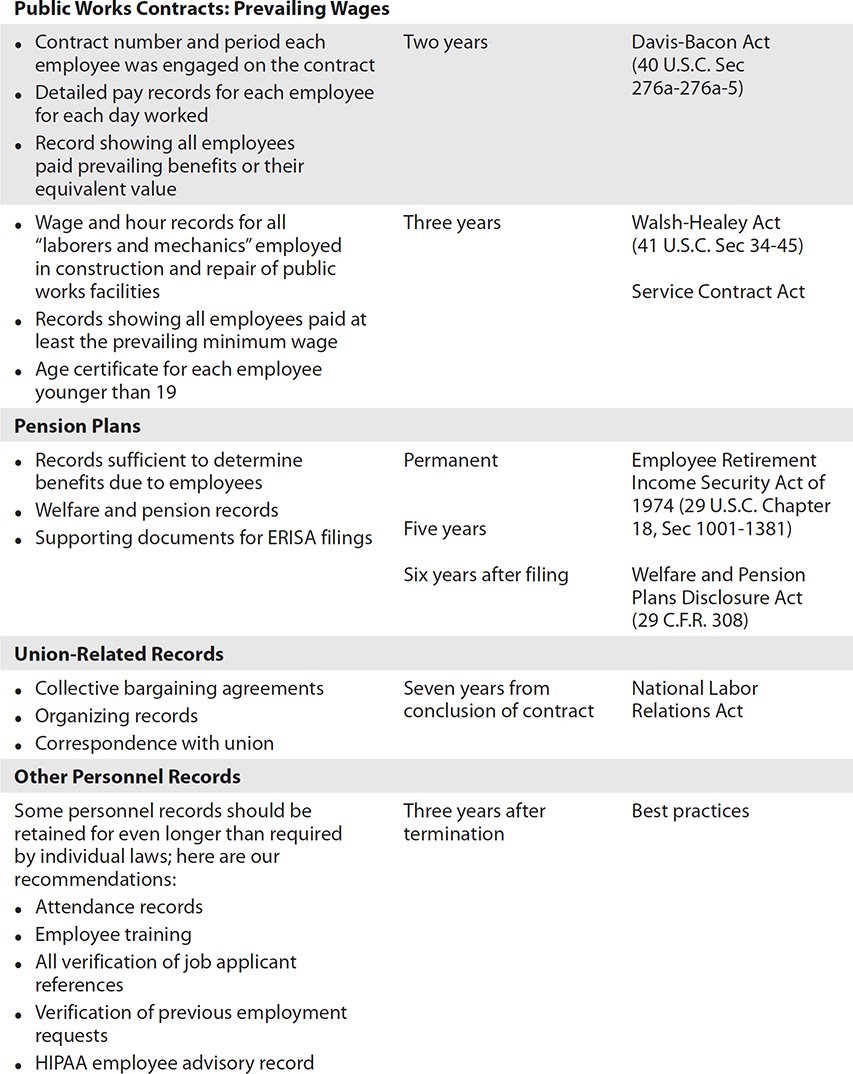

![]()

Anytime a strategic decision is contemplated that involves placing a workforce in a distant location, HR has some responsibility for contributing portions of due diligence in that process. What is the workforce talent pool? What are the local laws and customs that will influence operations? What will be the approach to product quality in the new location?

HR Global Abilities Experts say that some of the core competencies international HR careers demand are the same as those for domestic HR professionals—the skills are just on a heightened scale. For example, global HR managers need effective communication skills, including the ability to listen well.18 It is common for international HR professionals to be multilingual. It is often a job requirement. Here are some questions you should include in performing due diligence for HR management in a new distant work location:

• What is the wage structure?

• What is the tax structure for payroll in addition to operational taxes?

• What is the real estate situation?

• How will telecommunications, Internet, and transportation be provided?

• How much government regulation will be involved in managing a workforce?

• How ethical are the government, political influences, or business environments?

• What is the quality of life in the new location?

• Is there a history of labor unrest or political upset?

• Have there been any natural disasters? What is that likelihood?

• How can IT security be addressed?

• What are the possibilities for intellectual property rights and personal and property security?

• Is the economy stable? How widely does the currency exchange value fluctuate?

• What cultural differences are there?

• Is there a qualified labor force available?

HR Global Tasks On a global level, HR professionals must work toward helping the organization achieve its maximum value. Strategically, HR must help balance the priorities of headquarters and subsidiaries. How can human resources be distributed and balanced within budget restrictions and still maximize goal achievement? On a tactical level, HR professionals must facilitate management groups so that different disciplines and professions can achieve joint goals within differing cultural and sociopolitical environments.

HR Global Skills HR professionals must be capable of doing a lot of things that require professional HR skills. Here are some of the skills HR professionals must possess in the global workplace:

• Develop a strategic view of the organization How does value get created? What can HR contribute to the strategic plan development of the organization?

• Develop a global organizational culture Training plays a key role, and HR needs to be the training provider. How can communication issues be overcome?

• Secure and grow a safe and robust talent supply chain Work for a ready supply of leaders at each global location. Monitor the availability of qualified workforce candidates at all levels. Support efforts to develop a strong employer brand.

• Use and adapt HR technology Assure HR technology can be applied at all locations globally. Work with IT professionals to assure technology supports both domestic and global operations.

• Develop meaningful metrics Develop and implement consistent measurement devices and their application at all global locations. Be sure it is obvious that employee investment supports strategic goals.

• Develop policies and practices to manage risks Assure health, safety, and security of employees. Protect physical assets and intellectual property of the organization. Assure all legal requirements are being met at all global locations, including safety requirements, nondiscrimination requirements, payroll requirements, benefit requirements, and ethical requirements.

Auditing Global HR Practices It is important to know how your global HR practices are actually serving your organization and its people. To determine that, you will need to assemble a global compliance audit project team. Consider these types of representatives in your team selection process:

• Headquarters HR representative

• Foreign location HR representative

• In-house legal counsel

• Compliance officer

• Outside legal counsel

• Outside international HR expert

• Corporate audit department representative

An audit of global HR practices would be advisable if you have received a lawsuit challenging your HR practices, you are going through a merger or acquisition, you are undergoing corporate restructuring, you want to be sure you are complying with antibribery and insider trading laws, or you simply want to be sure your practices are being followed.

An audit should begin by identifying the countries that are involved. Next, define what focus you want the audit to have. Will it look at legal compliance, union contracts, corporate policies, or simply best practices? It is possible to take in all of these focal areas, but that becomes more complex.

Will your audit look only at local host country employees, or will you include expatriates, consultants, independent contractors, international transfers, temporary workers, or some other group? Will the audit engage in examining international payroll tax laws or data security issues?

Build a master checklist of areas to be examined. Then, expand that into a matrix that includes individual team member assignments, expected completion date for each component, and the ultimate audit report completion. Be sure you include time for a review process by identifying who will be involved in the review and approval sequence and how long each contributor will have to submit approval or additional report requirements. Finally, determine who will receive the final report when it is issued. What role will the report have in legal filings with organizations such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or other similar oversight group?

Becoming a Multicultural Organization

![]()

Organizations cannot become multicultural by proclamation. It takes concerted effort.

Developing a Global Mind-Set

Personal development precedes organizational development. First leaders must develop their own global mind-set. Then they will be able to help guide their organization into the same way of thinking. Here are five steps toward that goal:19

• Recognize your own cultural values and biases Developing a strong self-awareness has shown to foster a nonjudgmental perspective on differences, which is critical to developing a global mind-set.

• Get to know your personality traits, especially curiosity There are five specific traits that affect your ability to interact effectively with different cultures, listed here:

• Openness

• Flexibility

• Social dexterity

• Emotional awareness

• Curiosity

Ask yourself how open you are to different ways of managing a team. Are you flexible enough to attempt a different feedback style? How easy is it for you to strike up a conversation with people from foreign countries?

• Learn about the workplace and business expectations of relevant countries and markets Learn about the typical workplace habits, expectations, and best practices in other countries and cultures.

• Build strong intercultural relationships Just like when learning to speak a second language, it’s helpful to immerse yourself with people from other parts of the world to develop a global mind-set. These relationships facilitate valuable learning about what works and what doesn’t. The ability to form relationships across cultures is not a given, but the more positive intercultural relationships you develop, the more comfort you’ll have with diverse work styles and the less you’ll resort to stereotyping.

• Develop strategies to adjust and flex your style What has made you successful in a domestic or local context likely won’t help you reach the same level of success on a global scale, which is why learning to adapt your style is often the hardest part of mastering a global mind-set. This step involves expanding your repertoire of business behaviors by learning to behave in ways that may be unusual to you but highly effective when interacting with others.

Defining a Global Mind-Set We would define global mind-set as one that combines an openness to and awareness of diversity across cultures and markets with a propensity and ability to see common patterns across countries and markets.

Benefits of a Global Mind-Set The main benefit of a global mind-set is the organization’s ability to combine speed with accurate response. The organizational global mind-set can bring about benefits that can manifest themselves in one or more competitive advantages.

Acquiring a Global Mind-Set Acquiring a global mind-set requires you to recognize situations in which demands from both global and local elements are compelling; you need to be open and aware of diversity across cultures and markets with a willingness and ability to synthesize across this diversity.

Types of Cultures

Some people consider there are seven major cultures in the world today.

• Western culture This includes Anglo America, Latin American culture, and the English-speaking world.

• African American culture Also known as Black-American culture, this refers to the cultural contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or as distinct from mainstream American culture.

• Indosphere This is a term coined by the linguist James Matisoff for areas of Indian linguistic and cultural influence in Southeast Asia.

• Sinosphere The Sinosphere, or East Asian cultural sphere, refers to a grouping of countries and regions in East Asia that were historically influenced by the Chinese culture.

• Islamic culture This is a term primarily used in secular academia to describe the cultural practices common to historically Islamic people.

• Arab culture The Arab world stretches across 22 countries and consists of more than 200 million people. Arab is a term used to describe the people whose native tongue is Arabic. Arab is a cultural term, not a racial term, and Arabic people come from various ethnic and religious backgrounds.

• Tibetan culture Buddhism has exerted a particularly strong influence on Tibetan culture since its introduction in the seventh century. Buddhist missionaries who came mainly from India, Nepal, and China introduced arts and customs from India and China.

Definition of Culture Culture is the beliefs, customs, arts, etc., of a particular society, group, place, or time. It’s a particular society that has its own beliefs, ways of life, art, and so on, and it’s a way of thinking, behaving, or working that exists in a place or organization (such as a business).

How Types of Culture Affect an Organization Here are five types of corporate culture.20 Can you find one that describes your organization?

• Team-first corporate culture Team-oriented companies hire for culture fit first, skills and experience second. A company with a team-first corporate culture makes employee happiness its top priority. Frequent team outings, opportunities to provide meaningful feedback, and flexibility to accommodate employee family lives are common markers of a team-first culture. Netflix is a great example; its recent decision to offer unlimited family leave gives employees the autonomy to decide what’s right for them.

• Elite corporate culture Companies with elite cultures are often out to change the world by untested means. An elite corporate culture hires only the best because it’s always pushing the envelope and needs employees to not merely keep up but lead the way (think Google). Innovative and sometimes daring, companies with an elite culture hire confident, capable, competitive candidates. The result? Fast growth and making big splashes in the market.

• Horizontal corporate culture Titles don’t mean much in horizontal cultures. Horizontal corporate culture is common among startups because it makes for a collaborative, everyone-pitch-in mind-set. These typically younger companies have a product or service they’re striving to provide yet are more flexible and able to change based on market research or customer feedback. Though a smaller team size might limit their customer service capabilities, they do whatever they can to keep the customer happy—their success depends on it.

• Conventional corporate culture Traditional companies have clearly defined hierarchies and are still grappling with the learning curve for communicating through new mediums. Companies where a tie and/or slacks are expected are, most likely, of the conventional sort. In fact, any dress code at all is indicative of a more traditional culture, as are a numbers-focused approach and risk-averse decision-making. Your local bank or car dealership likely embodies these traits. The customer, while crucial, is not necessarily always right—the bottom line takes precedence.

• Progressive corporate culture Uncertainty is the definitive trait of a transitional culture because employees often don’t know what to expect next. Mergers, acquisitions, or sudden changes in the market can all contribute to a progressive culture. Uncertainty is the definitive trait of a progressive culture because employees often don’t know what to expect next (see almost every newspaper or magazine). “Customers” are often separate from the company’s audience because these companies usually have investors or advertisers to answer to.

Cultural Layers21

There are differing interpretations of culture. A metaphor describes it well: culture looks at it like an onion, consisting of layers that can be peeled off.

Schein’s Model22 In 1980 the American management professor Edgar Schein developed an organizational culture model to make culture more visible within an organization.

• Artefacts and symbols Artefacts mark the surface of the organization. They are the visible elements in the organization such as logos, architecture, structure, processes, and corporate clothing. These are not only visible to employees but also visible and recognizable for external parties.

• Espoused values This concerns standards, values, and rules of conduct. How does the organization express strategies, objectives, and philosophies, and how are these made public? Problems could arise when the ideas of managers are not in line with the basic assumptions of the organization.

• Basic underlying assumptions The basic underlying assumptions are deeply embedded in the organizational culture and are experienced as self-evident and unconscious behavior. Assumptions are hard to recognize from within.

Cultural Dimensions

Social scientist Geert Hoftstede suggests that there are six unique cultural dimensions that can be seen anywhere. These dimensions rank cultures on a scale of 1 to 100 for each dimension.23

• Power distance This dimension displays how a culture handles inequality, particularly in relation to money and power. In some cultures, inequality and hierarchal statuses are a way of life.

• Individualism versus collectivism This dimension focuses on the unification of culture. In individualistic cultures, the population is less tightly knit, and there is an “every man for himself” mentality.

• Masculinity versus femininity In this dimension, a culture is measured on a scale of masculinity versus femininity, which represents a culture’s preferences for achievement, competition, and materialism versus preferences for teamwork, harmony, and empathy.

• Uncertainty avoidance Have you ever been in a situation where a new idea or element is introduced? How did you react to that? For this dimension, cultures are gauged on their response to ambiguity and new ideas and situations. Change in the future can be a terrifying notion for some, while others will see it as an exciting possibility.

• Long-term orientation versus short-term orientation When dealing with the present and future, a culture either will look to innovate when facing new challenges or will look to the past for answers.

• Indulgence versus restraint In the final dimension, all cultures acknowledge that the natural human response in life is the urgent need to gratify desires. However, each culture will answer this need by either enjoying (indulgence) or controlling (restraint) those impulses.

Hall’s Theory of High- and Low-Context Cultures Hall defines intercultural communication as a form of communication that shares information across different cultures and social groups. One framework for approaching intercultural communication is with high-context and low-context cultures, which refer to the value cultures place on indirect and direct communication.24

Hofstedes’s Dimensions of Culture25 Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is a framework for cross-cultural communication, developed by Geert Hofstede. It describes the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis.

Hofstede developed his original model as a result of using factor analysis to examine the results of a worldwide survey of employee values by IBM between 1967 and 1973.

Trompenaars’s and Hampde-Turner’s Dilemmas Anglo-Dutch gurus Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner have become the go-to guys on multinational mergers. Their recipe: making opposites attract.26

If you followed dilemma theory to its logical conclusion, you would attribute every pernicious culture clash, and most other management problems, to the human habit (especially common in Western cultures) of casting life in terms of all-or-nothing choices: winning versus losing strategies, right versus wrong answers, good versus bad values, and so on. As a manager, when you unconsciously approach a business issue (or any issue) as a contest between good and evil, you lose sight of the potential benefits the “evil” side has to offer. It’s far better to interpret, say, the battle between English and French management styles or American dominance and European resistance as a dilemma that can be reconciled when both sides see they have something to learn from the other.

Cross-Cultural Challenges for HR27

With the rapid increase in the globalization of business, workforces are becoming increasingly diverse and multicultural. Managing global workforces has increased pressure on human resource managers to recognize and adapt to cultural differences, which when ignored can result in cross-cultural misunderstandings. With the growing significance of developing economies in the global business environment, human resource management is facing increased difficulty in managing cross-border cultural relationships.

Challenges of Culture As workplaces become more complex and the mingling of cultures becomes more challenging, HR professionals must keep an eye open for these specific challenges:28

• Colleagues from some cultures may be less likely to let their voices be heard.

• Integration across multicultural teams can be difficult in the face of prejudice or negative cultural stereotypes.

• Professional communication can be misinterpreted or difficult to understand across languages and cultures.

• Navigating visa requirements, employment laws, and the cost of accommodating workplace requirements can be difficult.

• There may be different understandings of professional etiquette.

• There may be conflicting working styles across teams.

Dilemma Reconciliation The essence of the reconciliation of a dilemma lies in the recognition that a dilemma is a nonlinear problem and therefore needs a nonlinear problem-solving approach. It replaces “either-or” thinking with “and-and and through-and-through” thinking.29

Creating Cultural Synergy Cultural synergy is a term coined from work by Nancy Adler30 of McGill University that describes an attempt to bring two or more cultures together to form an organization or environment that is based on combined strengths, concepts, and skills. High-synergy organizations have employees who cooperate for mutual advantage and usually tackle their problems by following a simple structure that focuses on identifying the problem, culturally interpreting it, and, finally, increasing the cultural activity. Contrary to this, there are low-synergy organizations that work with employees who are ruggedly individualistic and insist on solving any problem alone.

Managing Global Assignments

Only 51 percent of companies track the actual total cost of international assignments, yet 69 percent say there is pressure to reduce mobility program costs, according to a recent survey report on global mobility trends and practices. In addition, 76 percent of companies do not compare the actual versus estimated cost at the end of an assignment, and a whopping 94 percent do not measure the program’s return on investment.31

Strategic Role of Global Assignments

Global assignments can contribute to the organization’s strategic plan. They offer cross-training for senior managers and executives. This can enhance cultural exposure and even cultural emersion. Global assignments also provide an opportunity to assess global presence and expansion plans.

Types of Assignments

Specialists in international human resource management identify different types of global assignment. Technical assignments occur when employees with technical skills are sent from one country to another to fill a particular skill shortage. Developmental assignments, in contrast, are typically used within a management development program and are used to equip managers with new skills and competencies. Strategic assignments arise when key executives are sent from one country to another to launch a product, develop a market, or initiate another key change in business strategy. Finally, functional assignments resemble technical assignments but differ in one important respect.32

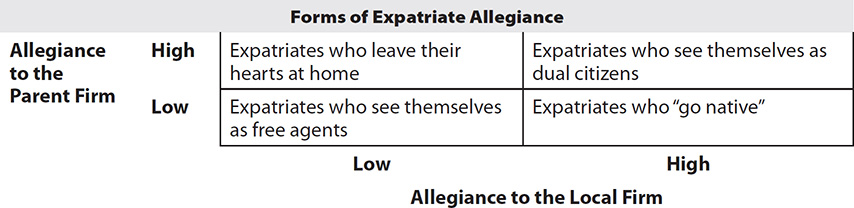

Managing Allegiances

Sometimes people are torn between their parent company and their local company. According to Kate Hutchins and Helen De Cieri, those allegiances can be understood by using the following chart:33

Global Assignment Guidelines

The companies that manage their expats effectively come in many sizes and from a wide range of industries. Yet they all follow three general practices.34

• When making international assignments, they focus on knowledge creation and global leadership development. Many companies send people abroad to reward them, to get them out of the way, or to fill an immediate business need. At companies that manage the international assignment process well, however, people are given foreign posts for two related reasons: to generate and transfer knowledge and to develop their global leadership skills (or to do both).

• They assign overseas posts to people whose technical skills are matched or exceeded by their cross-cultural abilities. Companies that manage expats wisely do not assume that people who have succeeded at home will repeat that success abroad. They assign international posts to individuals who not only have the necessary technical skills but also have indicated that they would be likely to live comfortably in different cultures.

• They end expatriate assignments with a deliberate repatriation process. Most executives who oversee expat employees view their return home as a nonissue. The truth is, repatriation is a time of major upheaval, professionally and personally, for two-thirds of expats. Companies that recognize this fact help their returning people by providing them with career guidance and enabling them to put their international experience to work.

What Managers Should Know Global human resource managers can use the high failure rates of international job assignments to support investing in up-front and ongoing programs that will make international assignments successful. Selecting the right person, preparing the expat and the family, measuring the employee’s performance from afar, and repatriating the individual at the end of an assignment all require a well-planned, well-managed program. Knowing what to expect from start to finish as well as having some tools to work with can help minimize the risk.35

The Global Assignment Process

There are five stages involved in the global assignment process.

• Stage 1: Assessment and selection Determining who will be appointed to the international job opening depends on who meets the job requirements in the best way. There may be a formal assessment, or there may be only a single selecting manager who makes the decision.

• Stage 2: Management and assignee decision The selecting manager determines how long the assignee will have to accept or reject the appointment.

• Stage 3: Predeparture preparation Before anyone leaves the home country, there are important considerations to be processed and questions answered. What are the immigrant requirements in the destination country? What visa requirements must be processed? What provisions will be made for the employee’s family members (school or spouse work appointment)? What about selling a home before departure? Will a home be purchased in the destination country?

• Stage 4: On assignment When the employee arrives at the new job location, there is a “settling in” process. Are the living arrangements going to be satisfactory? Where is the local grocery store? What about dentists, optometrists, and physicians? What about automobiles?

• Stage 5: Completing the assignment When the expat comes home, there should be a debriefing process that could last several days. Inquiries should be made about the employee’s opinion of the job environment, the work itself, the support received from the employer, and what things could be done differently.

Navigating the Global Legal Environment

There are always labor-management laws to be considered regardless of where one works in the world. They vary greatly in their control over the workplace, but both employee and the employer should understand them for the destination country so no one violates one of them even by accident.

World Legal Systems

Around the globe there are several different types of legal systems, and they don’t always agree with one another.

Types of Legal Systems

Civil law, common law, and religious law are the three primary kinds of legal systems in the world today.

Civil Law Civil law systems have drawn their inspiration largely from the Roman law heritage that, by giving precedence to written law, have resolutely opted for a systematic codification of their general law. It is the most widespread system of law in the world.

Common Law Common law systems are legal systems founded not on laws made by legislatures but on judge-made laws, which in turn are based on custom, culture, habit, and previous judicial decisions throughout the world.

Religious Law The Muslim law system is an autonomous legal system that is of a religious nature and predominantly based on the Koran.

Key Concepts of Law

While laws bring us some level of consistency in treatment for the same or similar events, there are some key elements that you should recognize in all of them.

Rule of Law The rule of law is the principle that law should govern a nation, as opposed to being governed by decisions of individual government officials.

Due Process Due process acts as a safeguard from arbitrary denial of life, liberty, or property by the government outside the sanction of law.

Jurisdiction Legal jurisdiction applies to government agencies as well as courts. State courts have jurisdiction only in their state. Federal courts have jurisdiction over federal matters. Federal case law is determined by appellate courts, and those decisions apply only within the jurisdiction of the appellate court. The U.S. Supreme Court has jurisdiction over all matters of the U.S. Constitution.

Levels of Law

Each governmental strata can offer its own laws.

Within a Nation At the national level, there can be laws created that apply to the entire country and others that apply only to a subset of the nation.

National Laws Federal laws apply to all governmental subsets such as states in the United States. Nondiscrimination rules apply to all states equally. Of course, there are qualifying thresholds such as the number of employees that can cause certain employers to be exempt from the provisions of the law, but all those who qualify by employee head count will be expected to comply with the national law.

Subnational Called a nation-state, canton, or province, each smaller entity within the federal umbrella can create its own laws. These laws apply only within its own jurisdiction.

Between and Among Nations When nations agree that the same laws should apply to each of them, one of the following types of rule would come into existence.

Extraterritorial Extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ) is the legal ability of a government to exercise authority beyond its normal boundaries. Any authority can claim ETJ over any external territory they want. This is the stuff that wars are fought over. The European Union and the World Trade Organization are examples.36

Regional/Supranational A supranational organization is an international group or union in which the power and influence of member states transcend national boundaries or interests to share in decision-making and vote on issues concerning the collective body.

International This is a body of rules established by custom or treaty and recognized by nations as binding in their relations with one another.

For example, EU law is divided into primary and secondary legislation. The treaties (primary legislation) are the basis or ground rules for all EU action. Secondary legislation—which includes regulations, directives, and decisions—is derived from the principles and objectives set out in the treaties.

Background The European Union was set up with the aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbors, which culminated in World War II. As of 1950, the European coal and steel community began to unite European countries economically and politically to secure lasting peace. The six founding countries are Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The 1950s were dominated by a Cold War between East and West. Protests in Hungary against the Communist regime were put down by Soviet tanks in 1956. In 1957, the Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community (EEC), or Common Market.37

With the collapse of communism across Central and Eastern Europe, Europeans become closer neighbors. In 1993, the single market was completed with the “four freedoms” of movement of goods, services, people, and money. The 1990s was also the decade of two treaties: the Maastricht Treaty on European Union in 1993 and the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1999. People were concerned about how to protect the environment and also how Europeans could act together in security and defense matters. In 1995 the EU gained three more new members: Austria, Finland, and Sweden. A small village in Luxembourg gives its name to the Schengen agreements that gradually allowed people to travel without having their passports checked at the borders. Millions of young people study in other countries with EU support. Communication was made easier as more and more people started using mobile phones and the Internet.

Legal Institutions Here are the current institutions serving the European Union:

• The European Parliament (EP) and its 751 members represent the citizens of the member states and are directly elected every five years. The Parliament makes decisions on most EU laws, together with the Council of the EU, via the ordinary legislative procedure. Parliamentary positions are prepared by 22 committees, which work on different policies, and adopted during plenary sessions held in Strasbourg or Brussels. Seven political groups have been established at the European Parliament for the current term of office.38

• The European Council comprises the 28 heads of state or government of the member states and sets the EU’s overall political agenda. The president of the European Council, whose primary role is to coordinate and drive forward the work of the European Council, is elected by the members of the European Council and can serve for a maximum of 5 years.

• The European Commission is the executive branch of the union. It represents the interests of the European Union and is composed of 28 commissioners (one from each member state) and chaired by a president. The latter is nominated by the European Council and appointed by the European Parliament for a term of five years. The commission has 35,000 staff members working in 33 different departments known as directorate-generals (which represent specific policies) and 11 other services. The commission is the only EU institution with the right to propose legislation as part of the ordinary legislative procedure. It also ensures that EU legislation and the EU budget are properly implemented, and it represents the European Commission in international negotiations.

• The Court of Justice of the European Union reviews the legality of the acts of the institutions of the European Union, ensures that the member states comply with obligations under the treaties, and interprets EU law at the request of the national courts and tribunals.

• European Central Bank is the central bank of the 19 European Union countries that have adopted the euro. Its main task is to maintain price stability in the euro area and so preserve the purchasing power of the single currency.

• The European Court of Auditors (ECA) mission is to contribute to improving EU financial management, promote accountability and transparency, and act as the independent guardian of the financial interests of the citizens of the union. The ECA’s role as the EU’s independent external auditor is to check that EU funds are correctly accounted for, are raised and spent in accordance with the relevant rules and regulations, and have achieved value for money.

Legal Instruments All of those institutions of the European Union rely on various legal instruments as the foundation of their work.

Treaties The European Union is based on the rule of law. This means every action taken by the European Commission is founded on treaties that have been approved voluntarily and democratically by all EU member countries. For example, if a policy area is not cited in a treaty, the commission cannot propose a law in that area. A treaty is a binding agreement between EU member countries. It sets out EU objectives, rules for EU institutions, how decisions are made, and the relationship between the EU and its member countries. Treaties are amended to make the European Union more efficient and transparent, to prepare for new member countries, and to introduce new areas of cooperation such as the single currency.

Regulations A regulation is a legal act of the European Union that becomes immediately enforceable as law in all member states simultaneously. Regulations can be distinguished from directives that, at least in principle, need to be transposed into national law.

Directives A directive is a legal act of the European Union, which requires member states to achieve a particular result without dictating the means of achieving that result. It can be distinguished from regulations that are self-executing and do not require any implementing measures.

Judicial Decisions EU case law is made up of judgments from the European Union’s Court of Justice, which interpret EU legislation.

Recommendations and Opinions Recommendations are without legal force but are negotiated and voted on according to the appropriate procedure. Recommendations differ from regulations, directives, and decisions, in that they are not binding for member states. Though without legal force, they do have a political weight. An opinion is an instrument that allows the institutions to make a statement in a nonbinding fashion, in other words, without imposing any legal obligation on those to whom it is addressed. An opinion is not binding.

Functional Area 12—Diversity and Inclusion

Here is SHRM’s BoCK definition: “Diversity and Inclusion encompasses activities that create opportunities for the organization to leverage the unique backgrounds and characteristics of all employees to contribute to its success.”39

Diversity and inclusion are linked together both by definition and by practice. Having a diverse workforce will not persist if that diverse group doesn’t feel included as individuals.

Key Concepts

• Approaches to developing an inclusive workplace (e.g., best practices for diversity training)

• Approaches to managing a multigenerational/aging workforce

• Demographic barriers to success (e.g., glass ceiling)

• Issues related to acceptance of diversity, including international differences (i.e., its acceptance in foreign nations or by employees from foreign nations)

• Workplace accommodations (e.g., disability, religious, transgender, veteran, active-duty military)

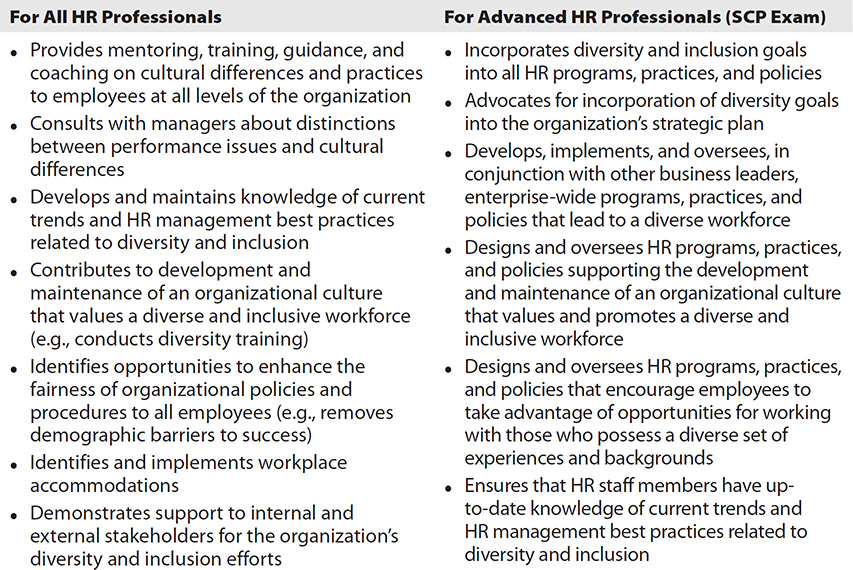

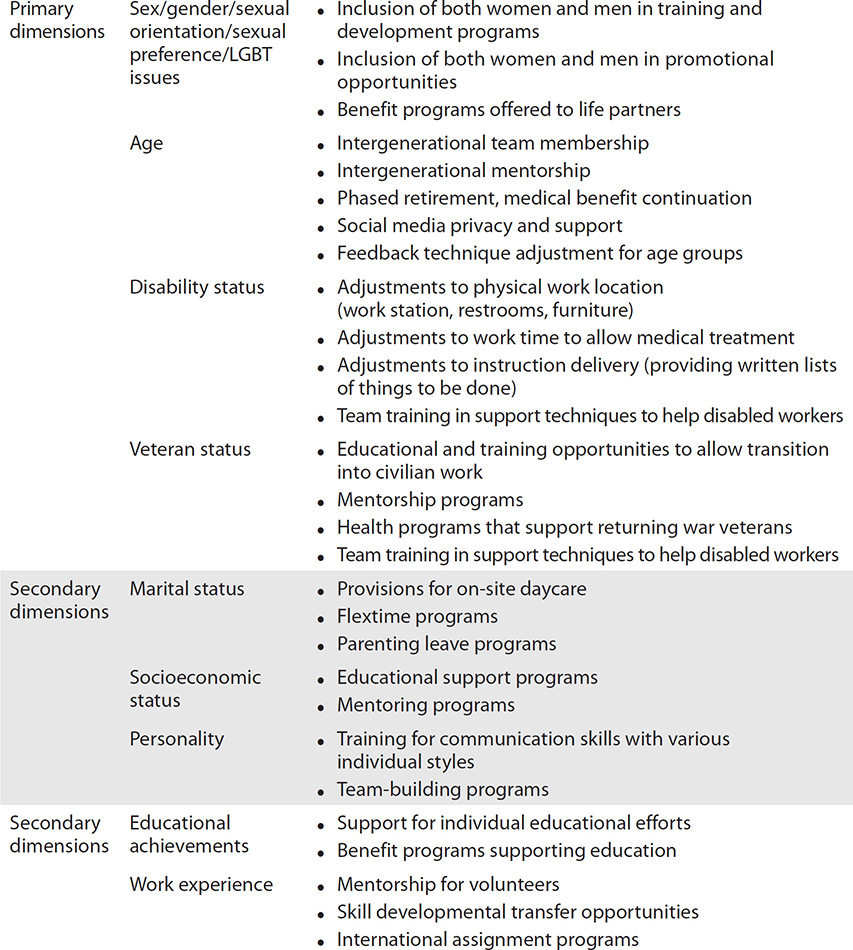

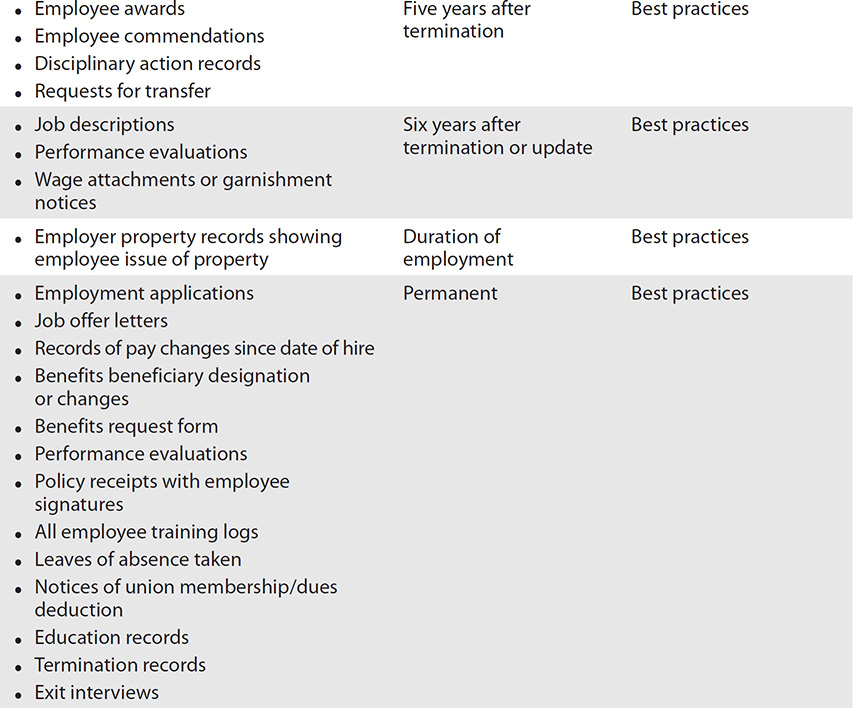

The following are proficiency indicators that SHRM has identified as key concepts:

![]()

Overview: Key Terms

The two key terms are diversity and inclusion. It is helpful to define them to understand how to incorporate them into an organizational culture and management.

Diversity

Diversity is a workforce characteristic. It indicates a mixture of social, cultural, and personal attributes that affect individual attitudes and behaviors. Diversity characteristics impact how others react to individuals “because they are different.”

Diversity of Thought Experiences are tightly linked to cultural background. Food, housing, recreation, and life activities are tied to the culture in which one grows up and matures. Thought processes and references are determined by the experiences people have had and the interactions with others that were part of those experiences. If we were rewarded early on for our “fresh ideas,” it is easier for us to generate ideas later in life. If we were encouraged to contain our behavior within strict boundaries of social decorum and not deviate much from those expectations, then it will be more difficult for us to be inventive or creative later in life.

Organizational leaders need to understand each individual’s background to understand how to encourage them to fully participate in the organizational workings.

Inclusion

Inclusion is the characteristic of a workplace referring to behaviors within the organization that determine how individuals are valued, engaged, and respected. Inclusion is also linked to “fairness” and equal access to resources and opportunities. You can see the link between inclusion and equal employment opportunity (EEO). While EEO is a legal obligation, inclusion goes further by valuing the importance of being part of the group in every way.

Diversity Without Inclusion Through a strong outreach program, it is possible that an organization can recruit a diverse group of employees. And it is possible that some of those employees may not be made to feel like a part of the company because they are not invited to contribute their ideas or suggestions. They may not be invited to participate in out-of-hours activities or assigned the really good jobs. Some folks may not be comfortable with co-workers because they look different or come from different cultures.

Any exclusion, whether subtle or overt, can lead to a feeling of being an outsider. So, diversity does not innately result in inclusion. Inclusion comes from conscious efforts. Inclusion depends on more than a lack of bias. It depends on commitment to assuring each person is welcomed as a participant in every facet of work life.

Diversity and Globalization

Not every culture in the world has the same view of diversity and inclusion as found in the United States. Some are theocracies, monocracies, or other monogenic countries. Whatever the circumstance, lack of variety in cultural experience makes it more difficult to accept, let alone encourage, recruiting a diverse group of job candidates. When it comes to selecting new hires, this cultural bias often plays a part in the hiring decision. That bias usually isn’t intentional. Yet it exists, and its results are seen in a high percentage of people in the organization that look alike. It may be based on religion or race or even gender. The differences in cultural experience are measured along a broad spectrum. From one country to another, the pointer along that spectrum line can shift dramatically.

Global Legal Distinctions Legal requirements for equal employment opportunity and diversity vary widely from one country to another. In some cases, imposition of quotas for some groups exists. Here are a few random examples. Equal employment opportunity requires some serious study of local and federal requirements in each political jurisdiction where you will have employees located.

• Australia Australia requires employers with 100 or more workers to report their gender equity plans and submit reports on the participation of women in their workforce and their board of directors.

• Canada Seven provinces and the federal government have pay equity legislation that requires employers to provide equal pay for work of equal or comparable value.

• Germany There are absolute quotas for the employment of severely disabled people based on the size of the employer workforce. Employers with 60 or more employees must have 5 percent of their workforce composed of severely disabled employees. Smaller quotas apply to smaller organizations.

• Great Britain The practice of a fixed retirement requirement at age 65 has been rescinded by law.

• South Africa There is a legal prescription for annual turnover thresholds. Exceed those limits, and affirmative action requirements will apply for recruiting and hiring. Protected groups include black people, women, and people with disabilities.

The Benefits and Costs of Diversity

A few years ago, the European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Industrial Relations, and Social Affairs conducted a study using input from 200 companies in four European countries.40 It identified some specific benefits and costs associated with employment diversity policies and programs.

The benefits of active diversity policies were determined to include the following:

• Strengthened cultural values within the organization

• Enhanced corporate reputation

• Helped attract and retain highly talented people

• Improved motivation and efficiency of existing staff

• Improved innovation and creativity among employees

• Enhanced service levels and customer satisfaction

• Helped overcome labor shortages

• Reduced labor turnover

• Resulted in lower absenteeism rates

The costs of diversity programs were determined to include the following:

• Costs of legal compliance Recordkeeping systems, staff training, policy communication.

• Cash costs of diversity Staff education and training, facilities and diversity support staff, monitoring and reporting processes.

• Opportunity costs of diversity Loss of benefits because a scarce resource cannot be used in other productive activities (diversion of top management time, productivity shortfalls).

• Business risks of diversity Plans taking longer than planned to implement or fail completely. This is known as the execution risk. Sustainable diversity policies are an outcome of a successful change in corporate culture.

The Four Layers of Diversity

According to Color Magazine,41 the four layers of diversity can be compiled into the four layers model, which has radiating rings from a center where personality constitutes the core.

• Personality This includes an individual’s likes and dislikes, values, and beliefs. Personality is shaped early in life and is both influenced by, and influences, the other three layers throughout one’s lifetime and career choices.

• Internal dimensions These include aspects of diversity over which we have no control (though “physical ability” can change over time because of choices we make to be active or in cases of illness or accidents). This dimension is the layer in which many divisions between and among people exist and which forms the core of many diversity efforts. These dimensions include the first things we see in other people, such as race or gender, and on which we make many assumptions and base judgments.

• External dimensions These include aspects of our lives that we have some control over, which might change over time, and which usually form the basis for decisions on careers and work styles. This layer often determines, in part, with whom we develop friendships and what we do for work. This layer also tells us much about whom we like to be with and decisions we make in hiring, promotions, and so on, at work.

• Organizational dimensions This layer concerns the aspects of culture found in a work setting. While much attention of diversity efforts is focused on the internal dimensions, issues of preferential treatment and opportunities for development or promotion are impacted by the aspects of this layer.

The Color Magazine article tells us, “The usefulness of this model is that it includes the dimensions that shape and impact both the individual and the organization itself. While the ‘Internal Dimensions’ receive primary attention in successful diversity initiatives, the elements of the ‘External’ and ‘Organizational’ dimensions often determine the way people are treated, who ‘fits’ or not in a department, who gets the opportunity for development or promotions, and who gets recognized.”

Implications of an Inclusive Definition In its simplest terms, a narrow definition will narrow impact to the organization. A broad definition will increase that organizational impact. There are many things that can be measured to determine whether the definition being used is broad enough for the organization. Some of them are job satisfaction, relations with supervisors and group members, intention to stay with the organization, commitment to the organization, job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, well-being, creativity, and career opportunities for diverse individuals. For many of these metrics, benchmarks will need to be established so direct application to any given organization can be accurately developed.

Visible and Invisible Diversity Traits

SHRM breaks down diversity into two categories, namely, visible diversity traits and invisible diversity traits. Basically, everyone matters.

Visible diversity traits are the more typical and visible areas associated with diversity such as race, gender, physical abilities, age, body size/type, skin color, behaviors, and physical abilities.

Invisible diversity traits include areas less visible such as sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic status, education, sexual orientation, military experience, culture, habits, education, native born/non-native, values/believes, and parental status, among other things.

Developing a Diversity and Inclusion Strategy

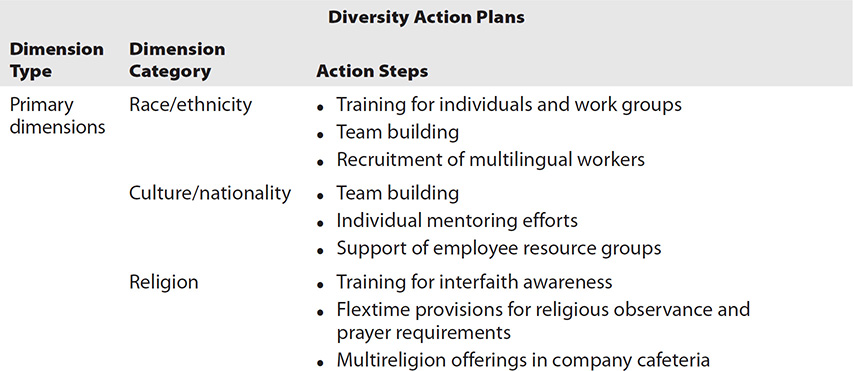

![]()

There is a key question to be answered at the beginning of any organizational policy discussion: What do you want to accomplish and how will you measure it? Strategy involves the plan for implementation. You must look at problems to be anticipated and identify alternatives for dealing with them. You must identify the value to be received from creating an executive steering committee that will monitor the program implementation. Once the alternatives have been assessed, strategy can be cited from the remaining options.

Why a Diversity and Inclusion Strategy?

Three reasons mark the need for a strategy to be used in creating and implementing a diversity and inclusion (D&I) program for any organization.

• Reason 1: Priority Without a strategy, the D&I efforts will always take a backseat to other more immediately urgent matters.

• Reason 2: Complexity D&I programs are not simple. The complexity requires organization-wide strategies if successful implementation is to be achieved.

• Reason 3: Resistance D&I programs require organizational change, regardless of the organization. There will be more change in some organizations than in others. Change is hard. Therefore, making the changes needed for successful D&I programs will take some significant effort.

The D&I Strategic Process

Once the decision has been made to develop and implement a diversity and inclusion program in your organization, you will need to identify the strategic steps you must take to achieve success.

Executive Commitment Changing organizational behaviors and individual attitudes are results that don’t come easily. If they are to be achieved at all, the highest level of executive will be needed to lay out the program, its reasons, and its objectives. Without the constant challenge and reinforcement from the senior leader, there can be no hope for reaching the established goals. “What the boss says is what gets done.” If the boss isn’t fully behind the program, it will just waste organizational resources and not accomplish what is hoped.

Making the Business Case for D&I The Conference Board published some thoughts in 2008 that still hold true today.42

• Business acumen and external market knowledge This becomes the foundation of understanding how a D&I program can support business needs. It includes the following characteristics:

• Executives understand and are current on global and local trends/changes and how they inform and influence D&I.

• Executives gather and use competitive intelligence.

• Executives understand diverse customer/client needs.

• Executives understand and are current with global sociopolitical environments.

• Executives understand context and lessons learned.

• Holistic business knowledge This requires understanding of the impact of the financial, economic, and market drivers on the bottom-line results. Additional requirements include the following:

• Executives understand core business strategies.

• Executives possess solid financial acumen.

• Executives use information from multiple disciplines and sources to offer integrated ideas and solutions on issues important to the organization.

• Diversity and Inclusion return on investment (ROI) This is where the financial impact of the D&I program becomes evident. Requirements include the following:

• Determine and communicate how D&I contributes to core business strategy and results.

• Create insights on how D&I contributes both to people and HR strategies as well as business results.

• Design and develop D&I metrics that exhibit the ROI impact.

Preliminary Assessment A quick way to determine how you are doing with your D&I program is to conduct an employee survey. It may take some professional help to identify the specific information you want to gather and the form of the inquiries you craft for each. But, surveying the workforce will help you understand the “state of the enterprise” about diversity and inclusion.

Infrastructure Creation If you are just beginning to address the issues of diversity and inclusion, it is important to recognize that there is going to be a need for some changes in the way you do things within the organization. Sometimes those changes can be uncomfortable for people, and that demands you be ready to give them the support they need to get past their discomfort to participate in the successful implementation of your program.