Storytelling for Audience Engagement

Take a moment right now and think back to a year ago. What’s the first memory that pops into your mind? What’s the first thing you can recall from 12 months ago? My guess is that whatever you remember, it’s tied to a strong emotion. It could be good, bad, happy, sad, or any of a million emotions in between. We, as humans, remember emotions first and details second.

As my all-time favorite quote from the great Maya Angelou states: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

This is why we tell stories. This is why we need stories in presentations. If you can weave information into one big story, or tie information forward or back to a story, you’ll connect an emotion to it. When there’s an emotion surrounding your content, it will be infinitely more memorable to your audience, and they’ll be more likely to take your desired action.

If stories connect emotionally (and I 100 percent believe that they do), that in turn immediately builds trust and rapport between you and your listeners and can shake them out of a staid mindset. When you present only data and facts, you keep your audience in “critical thinking” mode. When they’re restricted to thinking critically, their mind is more inclined to find ways to push back on, or shut down to, the information that you are giving them. Data and facts are important. Data and facts persuade, but emotion inspires people to take action.

Telling stories is also more enjoyable for everyone involved. Entertainment potential aside, our brains love a story. A satisfying story ending activates our sensory cortex and triggers the limbic system to release dopamine. Similar to the “runner’s high,” a story can make people feel better. And when your audience is feeling good, they’ll be more open to listening to your ideas, your data, or even difficult news.

Effective storytelling is a skill. Simply rambling off a bunch of stories with no previous thought, effort, or relation to your content won’t yield the benefits of emotional connection. But, never fear, it’s a skill you can learn. This chapter will help you discover how, when, and where to incorporate stories in your presentations to create that all-important emotional bond with your audience.

How to Tell a Story

With all due deference to Aristotle, there’s a bit more to storytelling than just a beginning, middle, and end. Any story you tell, be it 30 seconds or 30 minutes long, needs to have six elements: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

These six plot elements originate with a German playwright and author named Gustav Freytag, who lived in the nineteenth century. He created what came to be known as “Freytag’s Pyramid”: a graphic-based layout of what he discerned to be the most common dramatic story arc. His analysis of the structure of stories was spot-on, and still holds to this day. It can be found in plays, movies, and written stories of any kind. I simply call this the Story Map (Figure 7-1). It’s an easy way to navigate the action when creating a story to use during your presentations.

Figure 7-1. The Story Map

Chances are, you may be familiar with some of these terms. Good! Let me show you a breakdown of how they work in a real-life story. Like all of the stories in this book, this is true and from my life. I’ll use this story as our guinea pig and apply parts of it to the Story Map.

Exposition

“One of the many nonactor jobs I had while living in New York City was selling payroll for one of the big national payroll companies. I had a teeny-tiny territory in midtown Manhattan. It was three blocks long and two avenues wide. I spent a lot of time trying to get appointments with business owners and visiting as many small businesses as I could.”

This sets the scene of my story. I told you that I was an actor working at a payroll company (who), that I spent a lot of time selling payroll (what), that it was an event from my past (when), and that I lived in New York City (where). The rest of my story will encompass the “why.” I included some colorful details to help paint a picture for you, the listener.

Inciting Incident

“One day, I was sitting at the desk in my cube, making some cold calls, when my manager walked over to me with a big stack of papers. Because he knew I was an actor, he said, ‘Hey Kerri, you like to talk in front of people don’t you?’

“‘Yeah?’ I answered timidly, guarded about what his request might be.

“‘Here!’ he said as he threw all of the papers on my desk. ‘Tomorrow morning at 9 a.m., there are 20 CPAs coming to this office. You’re going to deliver this two-hour training on fringe tax benefits for New York State. Have a good night!’”

My manager’s request to deliver this last-minute presentation wasn’t something that happened every day. This inciting incident changed my course of action and made this day different from all of the other days that I sat at my desk making phone calls.

Rising Action

“I stared at the stack papers. It was a printout of a PowerPoint deck supporting the material that I needed to deliver. I didn’t know much about fringe benefits, but I was confident in my ability as an actor to analyze my ‘script’ and prepare to deliver a decent training session. So, I began like any good actor would.

“First, I read the deck and the training manual. I nearly fell asleep right there sitting in my cube. ‘Wow,’ I thought, ‘This really needs some help.’ I immediately started a talk-through out loud. I found areas of the training where I could tell some personal stories. I made notes on the printout of my PowerPoint deck and then got on my feet for my walk-through. A few hours later, I was ready for my dress rehearsal.

“It was after office hours, so I had the training room all to myself. I stood in the front of the room and I delivered the session just as I would the following morning. I felt pretty good and was ready to go. I packed up my stuff and headed to the subway to go home.”

I told you every step I took along the way after my inciting incident. In this story, my rising action elements happened to include the Rehearsal Process! However, I also told you what happened before I started my rehearsal, as well as what happened after.

The Climax

“During my subway ride, I was going over the presentation in my head. Did I have enough stories to tell? Would it be engaging? Were people going to leave with the information they need about fringe benefits?

“And then it hit me. ‘What this presentation needs is a costume!’ I thought to myself. As soon as I got back to my apartment, I rummaged through my closet and found an old leather jacket with fringe on the sleeves. That was it! That was what would make my presentation memorable! My plan was to show off the fringe on my jacket every time I said ‘fringe benefits.’”

The climax of the story, my big “ah-ha moment,” was the discovery that my presentation needed a costume. It’s the high point of my whole story. Everything that happens from here on out will be the descent to the finish.

Falling Action

“Then, the next morning, in front of 20 New York City CPAs, that’s exactly what I did.

“I presented the information at a good pace. I told a few stories that loosely tied back to the concept that I was introducing. I donned my fringed leather jacket over my business suit, and every time I said the phrase ‘fringe benefits,’ I opened my arms nice and wide so everyone could see the fringe. The audience watched me in a slightly stunned manner, but everyone stayed in the room for the entire two hours. For the duration, I got a lot of nonverbal encouragement; there were a lot of head nods and good eye contact from the audience throughout. I was pleased with my performance.”

In this case, the falling action of my story was actually the delivery of the presentation itself. Giving the performance, showing off the fringe, and receiving good feedback are all action elements that lead toward the resolution.

Resolution

“What I was most pleased with was that out of all of the payroll reps that delivered training that day, I was rated the highest. And I thought, ‘There is something to this rehearsal preparation and storytelling ...’ That was the very first seedling that became my company, Ovation Communication.

“Incidentally, I also learned that training sessions don’t need costumes.”

My resolution to this story always includes the overall point of the story (that my rehearsal and storytelling efforts made a difference), the lessons I learned (that training sessions don’t require a costume—whoops!) and the future action it sparked (the creation of my own company).

When I deliver this story in a presentation skills training session, I’m teaching the audience through my own actions—not only laying out an interesting story according to the Story Map, but tying it back to my content for that day.

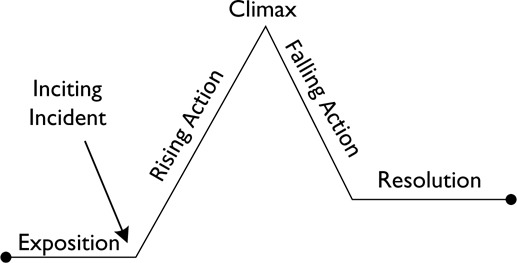

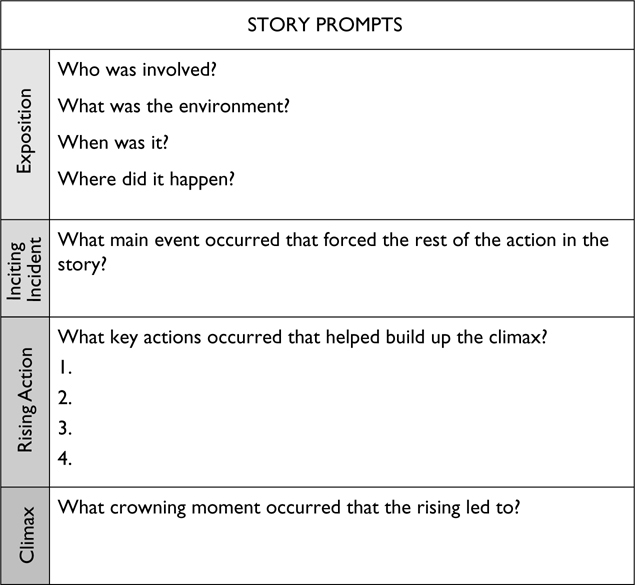

You’ve got plenty of stories from your own life that you can use to do exactly the same thing. I know you do. However, you want to make sure that, regardless of the story you tell, it follows the Story Map. If you’re not sure that’s the case, Figure 7-2 is a worksheet with questions to help you develop each of the points on the map.

Figure 7-2. Story prompts to get your story started

Incorporating Stories into Presentations

You can use a story or stories at any time during your presentation. There are, however, three specific applications where a story really shines: as an opener or closer, as a vehicle to put facts in context, and woven throughout your presentation. Each option is effective. They can ensure that your storytelling is purposeful and always related to your content.

Using a Story to Open or Close Your Presentation

A powerful place to use a story is right at the top of your presentation, as the attention grabber. Opening with a story lets your audience know they’re in for something different. If you launch right into a story (versus the old standby line: “Hi, my name is Kerri and I’m super excited to be here today.”), your audience will be pleasantly surprised and ready to listen to you.

Stories that start off your presentation don’t have to be long. Depending on how much time you have for your presentation, a 30-second or 1-minute story will suffice. In the case of a starter story, you don’t even necessarily need to speak directly to your content. It could be a mode for introducing yourself, or a foreshadowing of what’s to come. If you can actually make a connection between your opening story and your content, even better.

You can also use a story to close your presentation as your button. The button is going to solicit a reaction from your audience (hopefully applause) and let them know the presentation is over. It’s the last thing they’ll hear and might be the piece of information they remember most. A closing story will ensure that your all-important emotional connection with your audience remains intact.

Putting Facts into Context

Telling a story at any time gives your audience’s brain a nice break from the nitty-gritty, dry content, or heavy data you may be covering. After hearing a story and activating a different part of their brain—even if it’s just for a minute—they’ll be ready to jump back in and hear about numbers, codes, or any other details that may need to be presented, perhaps even with a better understanding of how they work.

A story can also be used to highlight some key points or put a fact into context. Perhaps a sagging set of sales numbers reminds you of the season when your favorite football team went from winning the Super Bowl to coming in last place in the league. The story of a downturn in production not only comes through but gets “underlined” with this example from another industry.

One of the things I cover when I speak on professional presence is a tip about how to quickly change your own mood. I like to highlight this key point, and put the fact into context, with this story:

“A few years ago, I was spending a training day with a group of eight speakers in Fargo, North Dakota. They were learning essential presentation skills, and I was helping them get ready for an upcoming conference. When lunch break rolled around, all the speakers left to eat, and I had a few quiet minutes in the room alone to check my phone.

“I had a number of missed phone calls and text messages from my husband telling me to call him immediately. I called him back and learned that our dog, a four-pound rescue Maltese, had suddenly passed away. This was a shock to me, and I was extremely sad.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to get upset. I had a very short lunch break. I was on-site at a client’s office, so maintaining my professionalism was extremely important—I didn’t want to be known as the trainer who cried.

“I took a few deep core breaths, and I smiled. Initially, I felt ridiculous. I felt sad, and I felt angry. But after just a few seconds of standing there smiling, I started to feel better. I continued to smile, maybe a minute more, and my mood lifted. I was able to get through the second half of the training day without falling apart and breaking down over the loss of my beloved dog.”

This story connects with the audience well and puts the tip into context. Many people have, or have had, dogs in their life. If not a dog, then, unfortunately, they’ve experienced the loss of something (or someone) vitally important at some point. By sharing my story of loss, and how I dealt with some of it in the moment, I’m connecting with their own emotional experiences of the same.

The piece of information that I want to highlight in my presentation is this: smile when you’re upset to trick your brain to thinking you’re in a better mood. My story not only utilizes that tip, but demonstrates a real-life application. It’s one thing just to hear a tip, fact, or step in a process. Tell how it was used in a real-life situation and the audience is more likely to remember the advice you’re giving them and take the action that you’d like them to.

Weaving a Story Throughout

Like most of the skills in this book, storytelling is flexible. There are many ways to do it effectively. But perhaps the most flexible application of storytelling is weaving a story throughout your presentation.

Begin your story as your attention grabber. Tell the audience a little bit more about your journey in each of the presentation’s transitions. Bring everything together and tell them the story end during the final part of your conclusion.

This adds great energy and interest to your content. It keeps the audience on the hook throughout your presentation, wondering what’s going to happen next. Often, the resolution of the story drives home a major take-away from your content—the life-changing thing about this information. When you weave a story into well-laid-out content, you’ve got a fully engaged audience.

Storytelling Is Fluid

I’m fond of each of these three applications. What’s great is that you don’t have to use just one of them! Mix them up, combine them, and come up with your own best practices. Tell a story as an attention grabber. Use another to highlight a major point. Weave yet another in and out of your presentation. The choice is yours.

If you’re new to storytelling and want to just dip your toe in the water, my best advice is to start with a short story as your attention grabber. This is a great way to test your comfort level with storytelling and gauge your audience’s reaction. I suggest trying this at the beginning versus the end because if it doesn’t go as smoothly as you’d like, you’ve still got your entire well-organized, well-rehearsed presentation to make up for it. But, if you use the Story Map and the Story Prompt questions to build your story, and apply the Rehearsal Process to it with as much care and time as you do for the rest of your presentation, you’re highly unlikely to deliver anything other than a fantastic, engaging story.

As humans, we love stories. Look at all of the money we spend on movies, music, television, books: we’re always looking to hear a great one. Your audience is already waiting to hear something good.

Actors know this secret: a waiting audience is always looking for you to succeed. So, be brave and tell them a story! You’ll offer them something really engaging; they’ll leave with useful details that they remember because of the emotional connection you’ve created. They’ll connect with the information coming out of your mouth, no matter how dry that information may be.

Manager’s Checklist for Chapter 7

![]() Stories create emotional connections. Embrace the idea of storytelling in your presentations!

Stories create emotional connections. Embrace the idea of storytelling in your presentations!

![]() Build a well-structured story around the points of the Story Map: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Build a well-structured story around the points of the Story Map: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

![]() Pick a way (or many ways) to incorporate a story into your presentation.

Pick a way (or many ways) to incorporate a story into your presentation.

![]() Openings and closings are great places to tell a story.

Openings and closings are great places to tell a story.

![]() Stories at any point can help put major points in context.

Stories at any point can help put major points in context.

![]() Stories woven throughout take your audience on a journey.

Stories woven throughout take your audience on a journey.

![]() Tell stories in the way that works for you, but make sure they’re detailed, truthful, and yours.

Tell stories in the way that works for you, but make sure they’re detailed, truthful, and yours.