1

___________

The Natural Laws of Perception

How People Perceive You

___________

WHEN KAREN ABRAMSON became CEO of Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting, she learned quickly that she was under a magnifying glass. In a 2014 interview with the New York Times, she revealed how surprised she was at the little things people around her started watching. “If I were seen having a conversation with somebody in the hallway, people assumed they were my best friend, though it was the first time I had talked to them all month.” Even her clothing drew scrutiny. After staff meetings she’d get feedback and suggestions on her style—including her lipstick color. “The first couple of times it happens, you feel very insecure, but then you learn to move on with your life,” Abramson told the Times.

Of course, astute leaders like Abramson know quite well that to simply “move on with your life” without considering the myriad perceptions we create along the way, many of them unintended, is bound to present some speed bumps on the road to leadership effectiveness. When Abramson discovered that people would act on an offhand comment she’d made, she became more careful. When she learned that her trademark blunt communication style led to unintended consequences, she softened it.

While you may have more flexibility in terms of self-expression at the senior level of management, the flip side is that people assign more weight to your messages, and as Abramson learned, may jump to conclusions and into action.

Executive presence is anchored in what others perceive, not what we intend to communicate. To paraphrase Robert Hogan, cofounder of Hogan Assessments: Others marry us, hire us, fire us, promote us, lend us money, and follow us, not because of what we think of ourselves, but because of what they think of us.

I often see firsthand how a blind spot to this crucial distinction threatens to upend the careers of otherwise talented and smart individuals.

One leader I worked with, Ross, the charismatic head of public affairs at a global public relations firm, was well connected and was reliable in bringing new business to the firm. He also considered himself the kind of manager who developed his team members, giving them opportunities to learn and grow and stretch beyond their comfort zone. But that’s not how his direct reports and peers perceived his delegation of tasks. These comments on his management style were typical: “His instinct is to delegate, but [he] doesn’t always do it in the most effective way; his instinct is to forward things to somebody without discussion and not necessarily keeping track of what he’s supposed to do and whether it’s his responsibility or somebody else’s. Everything is delegated. Can be frustrating sometimes. He is perceived as not being willing to do the work; he doesn’t like to get his hands dirty.”

Another client of mine was Danielle, a senior vice president in risk management for a global insurance firm. Danielle’s biggest strengths were her business acumen, her critical thinking skills, and her drive, which enabled her to see and seize opportunities within the business. She was perceived as someone who was driving the business forward rather than being passive. She also had excellent relationships with her direct reports, who loved her. But Danielle had a major blind spot. While she thought she was well positioned for a more senior executive role in an upcoming round of promotions, her bosses disagreed. They felt she needed to work on enhancing relationships with regional presidents and other individuals at more senior levels than she; that she needed to work on managing up; that she needed to get comfortable connecting with regional VPs and be more proactive in building those relationships. Danielle’s networking efforts had mostly focused on her operational network, consisting of the individuals whom she needed to engage to get the work done. In the process she lost sight of the importance of the type of personal and strategic networking that would have put her on the radar of key decision makers at more senior levels.

Both Ross and Danielle were strong contributors to the success of their respective companies. But their blind spots kept them from reaching their full potential. From what I’ve seen in my coaching practice, their predicaments are common. One biopharma CEO I coached viewed himself as “consensus seeking” while his leadership team saw him as indecisive. The VP of technology for a consumer products company considered himself “laid-back” while others interpreted his behavior as a lack of engagement. The director of provider relations at a regional health plan saw herself as a “humble leader,” but many of her colleagues saw her as a pushover who lacked confidence. All these executives expressed some dismay at how others got it wrong. But as we already know, their intentions weren’t what mattered. The perceptions of others did.

To develop our executive presence and understand our true impact on others, we must have a clear idea of the good, the bad, and the ugly of how we’re perceived. Self-awareness of our strengths and weaknesses is the key to this understanding, and I’ve devoted the entire next chapter to helping readers develop this ability.

Perceptions of Executive Presence

Some people don’t merely enter a room; they take possession of it. Their relaxed confidence is reflected in their walk, their posture, and the ease with which they engage others. Their eye contact is steady and their smile sincere. They’re socially appropriate in dress and conversation, and everyone they meet can’t help but feel their presence. Yet if that were all there is to executive presence, you’d be holding a pamphlet instead of a book right now.

Instead, authentic executive presence is a fluid combination of certain characteristics, behaviors, skills, and personality traits that all add up to a personal power that inspires and engages people. But while executive presence is complex, it is also attainable. Over two decades of coaching high-potential managers and leaders in the Fortune 500, I’ve found that anyone with a desire to change and grow can indeed develop this presence in all its facets.

My appreciation of what constitutes executive presence was formed in several ways: years of conversations with senior leaders about what executive presence looks like and the qualities they need to see in emerging leaders; close observation of respected leaders who bring out the best in others; research in the social sciences and leadership literature; and the failures of leaders who had talent and cognitive ability but nonetheless faltered due to an unwillingness to listen to feedback and adapt their behavior.

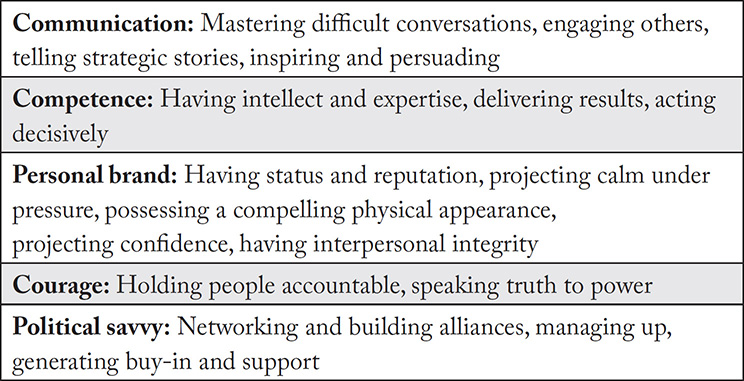

I’ve distilled my perspectives on executive presence into 5 categories and 17 distinct yet interdependent traits and abilities that I believe to have the biggest impact on this critical quality (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Traits of Executive Presence

We’ll be discussing all of them throughout this book.

It’s worth noting that we all have different executive presence profiles; we’re stronger in some areas and weaker in others. Similarly, our strengths may naturally emerge in some situations and waiver or even vanish at other times, perhaps when we’re under stress. For instance, you may give excellent presentations to peers and direct reports but bungle the same task in front of a more senior audience. Or you may be perceived to have executive presence in initial encounters due to your strong engagement skills and conversational savvy, but you may lose that distinction over time when others perceive—rightly or wrongly—that you’re mostly style over substance. The reverse may also be true, where your humble demeanor may initially be interpreted as timidity, but after some exposure it is viewed as a “quiet strength” that is an integral component of your leadership effectiveness.

The Path from Observation to Action

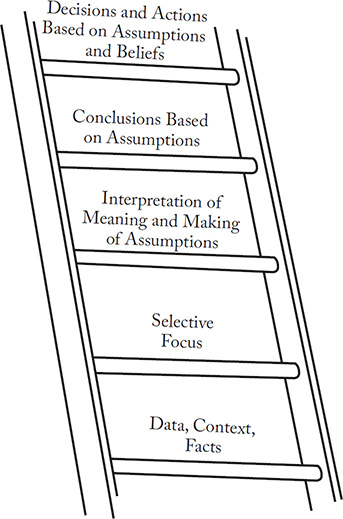

An easy way to understand how perceptions are formed and how people reach faulty conclusions is called the ladder of inference (Figure 1.2), a concept developed by organizational psychologist Chris Argyris. Made popular in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization, by systems scientist Peter Senge, this theory describes the journey that our general thinking process takes in leading us from observable reality—or facts—to our decisions and actions.

Figure 1.2 The Ladder of Inference

In this “ladder,” each rung represents a different stage in the reasoning process. It looks something like this:

1. We start with observable reality—the raw data, the context, and other “facts.”

2. We then selectively focus on certain aspects of this observable reality—the facets that catch our eye, often based on our interests, biases, beliefs, and prior experiences.

3. Then we try to make sense of what we perceive and make assumptions based on this meaning.

4. Next, we draw conclusions based on our assumptions that either reinforce our beliefs or alter them.

5. Finally, we make decisions and take actions based on what we believe to be true.

As you can see, the ladder of inference can be a useful checklist for determining whether our reasoning is based on verifiable facts or the subconscious influence of our beliefs and preexisting assumptions. It also shows clearly how easy it can be for people to climb up to certain conclusions that may lead to undesirable consequences. An example involving one of my clients illustrates this point.

When Jeremiah was promoted to executive managing director at a major financial services company, his leadership team almost doubled in size. In his former role, he valued loyalty and socialized with his team members in meetings, at lunch, and after hours; this approach lifted morale and created a strong team esprit de corps. But when he continued this behavior with his original team members after his promotion, he created the perception that he had an inner circle, a cadre of favorites, which alienated the new team members. This caused strife between the camps and throttled collaboration. While the warm friendships Jeremiah forged with members of his original, smaller team helped create a collegial atmosphere, this approach is rarely sustainable with larger teams, as perceived inequities will inevitably arise in terms of personal chemistry, attention, and distribution of rewards and resources.

The new team members’ conclusion that Jeremiah had an inner circle and their resistance to cooperating with these “teacher’s pet” colleagues affected more than the productivity of Jeremiah’s team. It also cast a shadow over his judgment as a leader; after all, a leader’s main job is to be inclusive and harness the talents and skills of all his people.

Jeremiah’s troubles remind us that we are constantly on display and that our behaviors are up for interpretation, for better or worse. Also, if we are in a leadership position, the results are often magnified.

Other Factors That Influence Perceptions

While we can’t very well control what others think of us, it can be helpful to understand some of the more powerful filters through which we all process incoming data that color our perceptions.

1. Stereotypes

To gauge the strength of stereotypes, consider an exercise that has been adopted by organizational psychologists in workshops across the globe. “Draw a leader” was the simple instruction that Tina Kiefer, a professor of organizational behavior at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom, gave to a room full of male and female executives. The results, regardless of gender, were that the executives would reliably draw pictures of males every time, attributing such equally imaginary leadership qualities to their creations as “Vision,” “Decisive,” “Charisma,” and “Listens.”

Yet in a study on leadership effectiveness that was published in APA’s Journal of Applied Psychology in 2014, “Women were seen as more effective leaders than men in middle management, business and education organizations.” The same study found that women were also seen as more effective in senior management positions, as rated by others.

Researchers from Florida International University analyzed over five decades of data and found that while men would generally rate themselves higher in leadership effectiveness, ratings by others often found women to be the more effective leaders across a variety of leadership contexts.

One way to combat “Man = Boss” stereotypes is to expose people to more women leaders and use strategic storytelling strategies to highlight their many contributions and achievements in general, and specific to an organization. Gender, of course, is just one of the stereotypes that executives may confront; ethnicity and race and many other traits have also prompted unjustified generalizations that these tactics can help to blunt.

2. Beliefs

Belief systems represent a view of the world, the ideas that a person holds as true and unquestionable, spanning everything from religion, cultural norms, and political affiliations to educational experiences, child-rearing, and leadership styles. Our various biases and learned preferences are the product of a lifetime of emotional and intellectual evolution, and they rest in part on things that are not provable. Then, when we encounter ideas, we’re drawn to the ones that support our current beliefs, selectively focusing on the confirming evidence and dismissing the contradictory evidence. Conversely, when we encounter ideas that violate our preexisting beliefs, we often bend over backward trying to disprove them.

Strategically, this means it’s often best to concentrate one’s efforts on influencing people who are on the fence about an issue, rather than people whose heels are dug in. New research may help in this regard. A study led by Princeton University showed that weakly held beliefs based on misinformation can be weakened or even rendered insignificant by repeatedly exposing the holder to correct information that is related to the misinformation. While the study centered mostly on such scientific topics as allergies, nutrition, and health, we might extrapolate the strategy to everyday management challenges. Say, for instance, that a leader is viewed as tough and difficult to work for. By repeatedly sharing accurate information and examples about her that illustrate that she has high standards but treats people fairly, those on the fence about the leader’s management style will grow more likely to remember the positive information and less likely to believe the negative stories. The key is to make sure the new information is related in nature to the misinformation and based on objective data, as opposed to just someone’s opinion.

3. Values

Closely aligned with belief systems is the filter of personal values. Indisputably, most people like people who share their values and are wary or even downright hostile to those who don’t. Unscrupulous politicians exploit this tendency, pitting us against each other by underscoring our differences rather than emphasizing our shared values to bring us closer together. An organization runs more smoothly when workers share its values—or at least abide by them during working hours. “Cultural fit” is often a criterion in the search for future company leaders, not least because those at the top set the tone for what’s expected, what’s rewarded, and what’s punished.

Yet despite best efforts to ensure that values are aligned, organizational life is often rife with interpersonal dust-ups triggered by clashing values. If, for example, you’re pushing a web developer to go live with a site that is still experiencing some functionality problems, but the developer stakes his reputation on everything running smoothly, then the conclusion he’ll reach in a nanosecond about your request is that you are very wrong! We are constantly faced with such challenges to our values. Sometimes, depending on how strongly we hold certain values, we may make concessions. Think of the senior executive who promotes a fellow Harvard alumnus over a more qualified candidate from a different alma mater. Although the senior executive values fairness and merit, he feels no harm will result if once in a while he lets emotional attachments tip the scale to favor a conflicting value. Nevertheless, generally speaking, our values frame our perceptions and guide us through all kinds of moral challenges. And if they don’t, they may not be values at all. To quote the inimitable philosopher Jon Stewart: “If you don’t stick to your values when they’re being tested, they’re not values. They’re hobbies.”

4. First Impressions

The power of first impressions has been so well documented that the utterance of the cliché about not getting a second chance can turn the utterer into Captain Obvious. And while we all know that the perceptions we create in initial encounters can have an outsized impact on how a relationship unfolds—if one does, that is—we’re often not sure what to do when it didn’t go so well. Because, you know, that second chance thing.

But don’t give up. First of all, new research from a series of joint studies by Cornell, Harvard, Yale, and the University of Essex reveals that most of us tend to think we did worse in initial encounters and conversations than we actually did. We think that our conversation partners like us less than we like them, and that the moments when others formed their opinions about us were generally more negative than the moments when we formed our opinions about them. We’re so wrapped up in our own worries about what we should say or do that we often miss signals of others’ positive affections toward us, the studies show. What to do? When you encounter someone for the first time, remember that we tend to view our performance negatively, and also remember that your counterparts in these meetings are themselves often plagued by the same insecurities and critical self-assessments. If you do these things, you will be able to relax a bit at these initial meetings, and by being relaxed and less focused on yourself, you really will make a better first impression than if you were anxious and in your head.

What if, though, an initial encounter really didn’t go so well; in fact, we barely blundered our way through? There’s bad news here but also good news, according to research by a team of psychologists from Canada, Belgium, and the United States. The bad news, as noted above, is that perceptions based on negative first impressions tend to stick like glue. Even when we have that second chance, any positive new perceptions we create are limited to the context in which they’re formed. For instance, say you made a poor first impression on a new colleague when you interrupted her several times during her presentation. After some time, you run into her again—at a company-sponsored community fund-raiser, say—and you end up having a pleasant chat, and your colleague realizes that you’re actually a nice person. Unfortunately, though, your colleague’s new, positive perception about you is limited to contexts like the fund-raiser event. The original negative perception about you will continue to dominate in all other contexts.

The good news? Forewarned is forearmed. If you have made a bad first impression, identify as many different contexts as possible in which you can create positive impressions that will help to weaken that negative initial impression. As one of the study’s researchers explained: “What is necessary is for the first impression to be challenged in multiple different contexts. In that case, new experiences become decontextualized and the first impression will slowly lose its power.” But if all you do is rely on the occasional friendly chat in the lunchroom to counter a bad first impression, you’ll only spin your wheels and miss valuable opportunities to build your executive presence.

We never run out of opportunities to make first impressions in life: There are the job interviews, client pitches, investor presentations, contract negotiations, meeting your new boss and colleagues for the first time, speaking at conferences—the list is endless. And that’s just at work. Each opportunity comes with its unique risks and rewards; do well, and you’re off to a good start with other opportunities sure to follow. Botch the whole thing, however, and the best that will happen is nothing. The worst runs the gamut from getting fired or not hired to being ignored, rebuked, cold-shouldered, or labeled a dud. To avoid such fates, I recommend keeping three simple yet powerful ideas in mind whenever you make your debut before a new audience: warmth, strength, and value.

Warmth, Strength, and Value Create Powerful First Impressions

Warmth

The first tool for making a powerful first impression and forging an emotional connection is warmth. Warmth fosters trust and puts people in the receptive frame of mind known to psychologists as an approach state, as opposed to an avoid state. Those opposite states stem from the ancient part of our brain, which is constantly scanning for pain or pleasure, for threat or reward. We want to know very quickly, from the moment we become aware of someone else, Is this person friend or foe? Can this person help me or hurt me?

Genuine warmth and the ability to engage others with socially appropriate behavior is one of the keys that can unlock the gates to mutual trust and liking. People are constantly asking themselves three things: What’s happening? What’s going to happen next? And how am I being treated? The answer to that last question is particularly important because people are highly protective of their status—i.e., how they view themselves in a group and how they’re seen by others. Being treated coldly or indifferently makes people feel rejected, which triggers a threat response in the brain that makes us shun new experiences—the avoid state. In fact, neuroscience research has shown that feelings of rejection affect the same areas of the brain that are involved in the processing of physical pain, which can often make us withdraw or lash out in anger. By showing warmth and sharing part of ourselves in initial encounters, we enable others to let their guard down as they assess our motives and intentions.

There are myriad ways to demonstrate warmth: by engaging rather than appearing passive, by relaxing our expression, by flashing a genuine smile (the so-called Duchenne smile that wrinkles the corners of the eyes), by nodding and displaying open body language and gestures. As the encounter proceeds, you can further demonstrate interest by asking the person questions about things that are important to him or her and by sharing something about yourself that will create trust and help the person relate to you. Remember, we’re drawn to those who share our values and avoid those who don’t.

Strength

Showing strength is a second tool for making effective first impressions. Such a display will boost perceptions of our competence and credibility, which also help gain the attention and trust of others. Strength is conveyed by the way you carry yourself, posture, tone of voice, eagerness to engage, and confidence. Even if you’re nervous, you must appear outwardly calm, or you’ll raise suspicions about your competence and readiness. Research has shown that strong reputations, significant achievements, and impressive networks are associated with executive presence, especially in initial encounters. The challenge is to demonstrate all this without being accused of braggadocio. But do not be so wary of that accusation that you say too little. When others are trying to gauge whether you can be trusted and are someone they want to affiliate with, you can benefit by association when you link yourself to people, organizations, and institutions that they trust and respect. Statements like “The way we solved these problems at Google . . . ,” or “After I finished my MBA in Boston, I decided to . . . ,” or “Mary Barra (CEO of General Motors) once asked me how . . .” can signal your achievements and associations without triggering your hearer’s gag reflex. Humility in recounting any such nuggets is important, but if it is to lead to more, it must be balanced with strength to give you solid footing in these initial encounters. What’s important to remember is, don’t do any of this to build yourself up or make yourself feel important. The entire purpose is to let the people in your audience know they are safe with you: They will not be wasting their time. They will be getting top value from you.

Value

Value is the third component of a powerful first-impressions strategy. But don’t be misled by one popular value theory, deemed the “elevator speech” approach. I understand the intention behind it—be concise in getting your point across; speak no longer than the duration of a short elevator ride. But the elevator metaphor is clumsy and as such often misinterpreted. What “point” are we talking about? Your idea for something? Your suitability for a job or assignment? Your ability to solve a problem? Better than wasting your time on crafting an elevator speech, think about how you can illustrate your value to a person, team, or organization. And say it for as long as it takes to say it, whether that’s 10 seconds or 2 minutes. By value I mean outcomes. What is the outcome you can effect? What is the end result we’ll get if we associate with you? What value do you contribute to the organization?

I’ve heard senior leaders say about someone they have known for a long while, “I still have no idea what he does.” Why? Because we frequently lose people at “Hello.” We flub the opportunity to communicate our value right from the start—the meaning of what we bring to the table, the outcome—so that people can know our purpose instantly and whether we’re someone they want on their team, or we’re someone worth listening to, or we’re someone who might be a good fit for a particular role.

Imagine that you had to introduce yourself to your peers, vendors, and customers at a conference for technology executives. A company whose public communication strategy I’ve long admired is Emerson Technologies, so I’ll use one of its award-winning advertising campaigns and imagine that campaign as an introduction in the following example.

Say an Emerson employee introduced himself like this: “My name is Bob Shaw. I’m the senior VP of engineering for Emerson’s digital scroll compressor technology for refrigerated food transport. Happy to be here.” This wouldn’t tell you much. It would go in one ear and out the other. And you’d likely forget you ever met this person.

But suppose he continued, “What this means is that my team helps companies like Dole protect and preserve the world’s most popular fruit—bananas—with precise shipping temperatures over thousands of miles of ocean travel to ensure fresh arrival at local stores.” This part of his statement sits squarely in the spirit of Emerson’s advertising campaign. It explains clearly the outcome of his work and the value to his customers and the end consumer: ripe yellow bananas, ready for consumption.

This sort of clarity and communication of value and outcome stimulates the reward center in our brain, because from a neuroscience perspective, our brains crave clarity and certainty, and those qualities make people more real to us and boost our perception of their presence. But most of us would just stop at the first part of the introduction—name, role, function, and maybe tenure at the company, none of which is very useful in terms of helping someone perceive value.

There are many other ways you can illustrate value. One is by offering a sort of proof of concept—evidence of your success or achievements, either organizationally or personally. Maybe you can mention how many units you’ve shipped, or how many orders you’ve processed, or the prestigious awards you’ve received, or the number of lives you’ve saved. When people perceive the value you’ve contributed to others, it’s much easier to imagine what you could do for them.

In the battle between reality and perception, perception wins every time. Therefore, if we keep in mind what’s important to others and the myriad ways their perceptions may be influenced, we can make informed decisions that add to rather than subtract from our executive presence.

In Chapter 2 we’ll explore how you can develop your self-awareness, which is the quality on which most of your success as a respected communicator and leader will ride.