8

___________

The Essentials of Managing Conflict and Improving Relationships

___________

ONE FACTOR THAT weighs heavily in the evaluation of a leader’s executive presence—at least from senior management’s perspective—is how well the business units or departments perform. This shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, reliably delivering results and achieving key outcomes through others is the raison d’être for executives. What appears to be less obvious to managers and executives, however, is that the key to success in meeting organizational objectives and assuring outcomes lies in the engagement of their employees, and that many, many employees are not so engaged. One only has to look at Gallup research, which found in 2017 that an astounding 85 percent of employees worldwide are unengaged in their jobs. And these numbers don’t budge very much from year to year, if you keep up with Gallup’s findings.

The quantifiable results of such low engagement are, unsurprisingly, low productivity, low customer satisfaction, and low unit financial performance. In fact, Gallup attributed approximately $7 trillion in lost productivity, globally, to low engagement. Other research has shown that the better the quality of the relationship between leaders and followers, the more engaged employees are, whereas low-quality relationships lead to sagging performance and even retaliation by employees against their leaders. Citing his own research, Dr. Robert Hogan of Hogan Assessments quipped at an assessment conference in Prague: “70 percent of American employees would take a pay cut if someone would fire their boss.” He continued, “People care more about how they’re treated than how they’re paid.”

Clearly, this is a call to action for leaders. A focus on building strong relationships at work can have a noticeable positive impact on one’s overall reputation as a manager and one’s perceived executive presence.

Of course, if you’ve spent more than a day or two wandering the halls or filling a cubicle in a corporation or another type of organization—including schools and federally funded bureaucracies—you know that somewhere between the lobby and the backdoor exit lies the potential for interpersonal friction. In fact, even if the head count of your organization amounts to only single digits, you probably have the scars to prove it. Anywhere two or more people occupy the same space, professional or otherwise, in the context of a shared mission and under the looming shadow of personal goals and desires, the laws of human behavioral dynamics kick in. When they do, sooner or later, conflict will erupt. It’s like weather to pilots and blood to surgeons: At the end of the day, success depends not on its avoidance (which is impossible), but on how well you land the airplane or sew up the patient. In other words, view these inevitable conflicts as opportunities to flex your executive presence, as chances to optimize the consequences of conflict. Conflict avoidance is a nonstarter strategy.

In one study on managerial effectiveness, the subordinates of 457 managers were asked to evaluate their bosses. The managers who were deemed most effective, as measured by the satisfaction and commitment of their subordinates and how well their organizational units performed, spent much more of their time motivating and developing people, and, most notably, managing conflict, than their less effective peers.

To be more effective in managing conflict, first learn about its more common causes.

Common Causes of Interpersonal Conflict

Most people don’t require a definition of conflict any more than they need to know what Webster’s says about hunger. However, in this case a definition can be helpful because conflict too often is written off as one party making another party angry by not giving the second party his or her way or by being obnoxious and unreasonable. Although this is a plausible definition, a better one is this: Conflict is a dynamic that occurs when one person does not receive the expected or desired response or behavior from another person.

This definition, of course, opens up a very expansive landscape of potential dust-ups. For rising executives whose organizational success depends on the support of various teams and other corporate stakeholders, the matrix of variables is deep and wide, resulting in a nearly infinite combination of combustible dynamics. Everything from personal values, to preferences and needs, to resentments and triangulated agendas, can furnish the spark that starts the fire. When conflict emerges from the frequent interactions of colleagues and peers or bosses and direct reports, it’s sometimes less an issue of who is right and who is wrong and more a matter of a stylistic difference: a clash of perspectives, occasionally seasoned with a dash of insensitivity. And in a conflict, a tiny speck of emotion can detonate an otherwise reasonable disagreement.

In his 1992 book The Eight Essential Steps to Conflict Resolution (later in the chapter we too will explore conflict strategies), Dr. Dudley Weeks presents the following seven sources of interpersonal conflict.

1. Differing Worldviews and Cultures

Don’t look now, but not everybody thinks the same way you do. You may have a fundamental difference of opinion with another person about a specific policy or situation, or the cause of the friction may be far broader: The two of you may view the world through vastly different lenses. Some corporate cultures value the giving and receiving of open and honest feedback; others prefer to “keep the peace” and avoid sensitive topics for fear of upsetting people. Some organizations value building consensus among the team for major decisions, whereas in others the boss makes the call and informs the team after the fact. Whatever the particular norms may be, if you didn’t “grow up” in that culture, you may bring a contradictory perspective to work. And if you can’t sign up for their way of doing things, the potential for interpersonal conflict is high. Fortunately, more and more organizations these days understand the need for diverse perspectives and welcome dissenting voices. But where cultures are deeply entrenched, the battle may be uphill.

2. Priorities

You’re fine with ambiguity; someone else needs crystal clarity. You think before you speak; someone else speaks in order to think. You believe the company should invest in a new facility; someone else thinks that’d be a huge waste of money that’s needed elsewhere. People differ in everything from decision making to communication styles to business strategy; in an eight-person department, in fact, you are likely to find eight different sets of needs and priorities. Each of them is a potential bomb when it collides with the needs and priorities of others.

3. Perception and Filters

As we’ve seen from Chapter 1, how we’re perceived by others may not remotely be how we see ourselves or intend to come across. And yet it’s the everyday reality we operate in. You may be challenging someone’s ideas in order to arrive at a better solution, but to the other person you may be seen as cunning and competitive. Similarly, you may think you’re adding value in a meeting, where others may see you as hogging the spotlight. While adjusting your style may smooth things over a bit, such misperceptions can lead to many conflicts that eat up precious time and detract from the real issues.

4. Power

Managers who rely on power to get compliance, without giving much thought to whether others buy in or are even engaged in the work, often bump up against an ugly reality. From active disengagement to outright sabotage, people find creative ways to rebel against dictators. Genuine influence, rather than raw power, is the better way to sidestep this type of conflict, no matter how hierarchical the organizational culture may be.

5. Values and Principles

If you work for a company whose values and norms you don’t share and can’t get on board with no matter how hard you try, you’ll be miserable on a scale that hurts your soul. Maybe you value working autonomously, but you’re being micromanaged to the nth degree. Maybe you want to do right by customers no matter what it takes, but your organization has strict rules that allow little flexibility in case of a dispute. Missed the deadline for a return? Sorry, customer; not our problem. If what you value doesn’t match the commitments you signed up for, conflict is pretty much woven into the fabric of your daily routine.

6. Feelings and Emotions

Especially on big projects, ones with massive investments of time, money, effort, and ego, emotions can interfere with rational thinking, and heated discussions can quickly escalate into a raging firestorm. One of my coaching clients, the general counsel and chief compliance officer at a fast-growing health insurance agency, whose job it is to keep the company’s stakeholders from running afoul of the law in a heavily regulated industry, often finds himself the bearer of bad news. In one instance he had to tell colleagues from business development that a project they’d been working on for months, an innovative marketing initiative to promote the company’s offerings to their provider network, would violate anti-kickback laws and could get the company barred from profitable governmental programs. As my client was new to the company and hadn’t yet established strong relationships, the business development team—emotionally invested in the initiative—said he didn’t know what he was talking about. This highly emotional clash prompted the CEO to hire two outside law firms to provide a second opinion on the matter. Later, at $50,000 in consulting fees, the law firms confirmed my client’s legal assessment. Although the resolution was expensive, this conflict was almost certainly unavoidable; heightened emotions had drowned out rational thinking and reasoned dialogue. In such cases, the more that awareness exists around individual hot buttons, emotional biases, or lingering feelings in a discussion, the more likely an efficient resolution to a conflict becomes.

7. Conflicts Within a Person

This catchall category could pertain to people who bring personal problems to work as well as those with neuroses, substance abuse problems, hidden resentments, and a host of other issues that, when not successfully managed, can easily lead to conflict and bring down entire teams.

Regardless of the source of the conflict, there are always stakes surrounding a successful resolution. When upwardly mobile managers and executives learn to recognize these and other originating sources as potential conflicts in the making, they can prepare for and minimize what seems to be an inevitable clash. From our discussions on social intelligence, you may already be equipped to read some initial warning signs. The following section provides additional tools.

How to Recognize and Prepare for Brewing Conflicts

The warning signs of impending interpersonal conflict in the workplace differ from person to person. Big red flags may be noticed, but someone who seems perfectly well adjusted may one day go off the deep end, up to and including the dark incidents that make the evening news. Given this wide range, it is better to look for behavioral and attitudinal variance in the people with whom one works. Someone who for years has been friendly and jovial but lately seems down and quiet may be a source of conflict in waiting. Changing patterns of attendance and tardiness can signal trouble, as can unexpected requests for time off or schedule or assignment changes—especially when motivated by a desire to get away from someone else. Increasing emotional outbursts and uncharacteristic moodiness are other warning signs.

Although it seems far-fetched to assume that any of these symptoms is signaling that an employee is ready to detonate, it’s prudent to look closely and see if you can somehow help. Such circumstances also present an opportunity to assert your executive presence; after all, interpersonal integrity and compassion are recognized hallmarks of executive presence. For instance, if a colleague is timid about coming forward with personal issues but his workplace behavior has turned troubling, take him for a coffee. By taking notice of the altered behavior, you can intervene in a supportive manner rather than the critical or threatening one that is common after conflict has surfaced. That early move can sap the energy out of whatever potential conflict resides just below the surface. In addition, the respect you’ll possibly gain from the interaction—or intervention—contributes to others’ perception of your executive poise.

Preparation for conflict resolution comes in two flavors: creating a means of prevention and offering resources for resolution. The former may include having an employee grievance process in place as well as a safe way to discuss issues with supervisors or coworkers in a confidential manner. Some companies offer counseling to employees whose problems warrant that level of attention, and others train managers in spotting conflict before it happens and intervening accordingly. If neither practice applies to your workplace, you can assert your status as a rising executive and approach appropriate stakeholders in the company—human resources might be a good place to start—to discuss the possible adoption of such programs. This is not a bad initiative to have on your curriculum vitae when promotion time arrives.

Back in the trenches, once a conflict has ignited, the response becomes trickier, especially when the supervisor or leading manager is part of the square-off. Firm company policies can mitigate the problem, such as a no-physical-contact rule whose violation can result in immediate termination, a take-it-behind-closed-doors rule, the availability of immediate mediation, and a culture of peer involvement and enforcement to help employees resolve issues quickly among themselves. An overarching corporate culture that prizes peacefulness, respectful debate, and comradeship is also highly valuable.

Choose Your Ideal Conflict Management Approach

Conflict is not inherently bad. If everyone agrees all the time or if no one is ever challenged out of fear of reprisal—in other words, if employees have no voice—by definition a cultural ceiling has been placed on the company’s potential. Conflict can be viewed as an opportunity to strengthen relationships and fortify cultures, though this can happen only when the ground rules and consequences line up with a process of healthy debate and open and honest conversations. Without a foundation of trust and the commitment to such rules of conduct (and in the presence of unfortunate consequences), relationships and cultures almost always take a hit when trouble arises.

In marriages and long-term relationships, for example, conflict is as opportune as it is inevitable. It presents a chance for the partners to clarify intentions, perceptions, needs, and feelings, to be heard and to hear. A committed relationship grows through conflict, or at least it should. In a perfect world, the result is an opportunity to make changes as part of the resolution process, to strengthen respect and solidify the process of meaningful communication. This principle works just as well in an organizational culture, corporate and otherwise, albeit with a wider range of personal issues and styles than in a marriage. When executed poorly, however, in either environment, the result is likely to be resentment, anger, and an ongoing agenda of revenge that can turn into a vicious circle of simmering conflict.

By understanding our own default conflict management style as well as that of others, we have the opportunity to make positive strategic and behavioral choices that reflect both a mature confidence and a desire to preserve valuable relationships—both qualities that can add to one’s executive presence.

A tool I’ve often used with clients to help them gain awareness of their dominant conflict management style, as well as alternative styles available to them, was developed by two professors of management from the University of Pittsburgh—Ken Thomas and Ralph Kilmann. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI™) is a simple self-assessment tool that can develop more productive conflict resolution behaviors. One of its key ideas is that none of the identified conflict styles are either good or bad. They are simply options that may suit one conflict situation better than another.

We all have our go-to conflict management styles. Some people prefer to avoid conflict altogether, whereas others strive to accommodate, collaborate, compromise, or push back (“competing” is what the TKI calls this more assertive style). A corollary is that we may overly rely on one style.

You may recognize your dominant conflict management style below, as well as take note of others you rarely deploy. By understanding the utility of all the styles, however, you’ll position yourself for quicker resolution of any conflict.

The Styles at a Glance

Thomas and Kilmann identify five conflict management styles. Competing, a power-oriented mode, pertains to someone who is primarily concerned with winning, with whatever power at his or her disposal and often at the other person’s expense. It isn’t as sinister as it sounds, and it can be a suitable choice at times, especially when it’s important to stand up for one’s rights, defend an idea, or win for the sake of the team. Other appropriate circumstances include crises and situations where rapid action is needed or unpopular measures—new rules, cost cutting—need to be implemented. Do you overuse the style? Maybe so, if people are loathe to disagree with you lest they get rebuked for speaking their mind, or if they commonly may put on a Potemkin-like facade of being more informed than they really are (which has obvious ramifications for a leader). Conversely, if you underemploy this style, you may fail to take charge or to exercise power when strong leadership is needed, or you may overly defer to others’ concerns and feelings when decisive action is required.

A second style, collaborating, involves seeking a solution that meets the needs of both parties. This style can help preserve relationships by demonstrating that the other person’s concerns are valid and that one is committed to finding creative solutions. It can also deepen one’s understanding of a controversial issue by seeing it from the opponent’s perspective. Overuse of collaborating can result in spinning your wheels and belaboring issues that don’t warrant that level of attention, and can also result in holding off too long on making a decision because of an eagerness to seek consensus. On the flip side, if you underemploy this style, you may notice that others lack the motivation to buy into your ideas because you convey the impression that their concerns are none of yours.

Then there is compromising, a style that may work when both parties are interested in moving things along and don’t mind giving something up in return. Both typically walk away satisfied to some degree, with a solution that may have come at a higher cost or lesser benefit if a different style had been used—say, competing or accommodating. If seeking compromise is your go-to resolution mode in any conflict, be aware that you may end up compromising some of your most important values in the process, all for the sake of a quick resolution that, in the end, may not serve your long-term goals. Conversely, if compromise is typically the last thing on your mind, you may sacrifice valuable opportunities to save a relationship or to get your fair share in a fierce competition for resources.

The conflict resolution style of accommodating is not the most assertive style but, like the others, may be the smart strategy to adopt in certain situations. Use it when it’s important to keep the peace and prevent a conflict from escalating—especially if you have little stake in the outcome or it matters far more to the other person than to you. Accommodating may also be the best option when it’s time to align with the boss or the team after a difficult decision’s been made and you want to show you’re a team player. Accommodate as a matter of routine, however, and you may come across as a pushover. If, on the contrary, to accommodate is anathema to you, you may be labeled “difficult to work with” and a person who is unreasonable and unwilling to take one for the team.

Finally, there is avoiding. While I mentioned earlier that it’s virtually impossible to avoid conflict in an organizational environment, avoiding is a conflict management style that can be used when it makes sense to remove oneself from an emotionally charged situation, avoid giving oxygen to a trivial matter, or wait for a more opportune time to discuss a controversial issue. One sign that you may be too much of a conflict avoider, though, is that colleagues notice and talk about your lack of input on challenging topics. You appear to be missing in action when it comes to taking a stand on an issue, making tough decisions, or debating solutions to niggling problems. But if you use this style rarely, you may get embroiled in too many issues not worth your time or effort, sapping you of valuable mental energy. You may also come across as thin-skinned and quick to jump into an argument without first considering the stakes. This, in turn, can impact others’ perception of your judgment, a key component of executive presence.

Diagnosing Style Conflicts

When the new CEO of a global food manufacturer asked me to work with Rob, a member of his senior leadership team and the CFO of the company, to help him develop his executive presence, I asked what he felt was missing. “I don’t feel like I have a good business partner in him,” the CEO responded, and “Rob seems disengaged in meetings and appears to constantly undermine my authority as CEO in front of others.” When I interviewed Rob, he had a different take on this interpersonal conflict: “When I offer my perspective on an issue, in meetings or in private, all I get is a brush-off or silent treatment,” he complained of his boss. “I don’t feel like he respects me or even wants me in the position.”

Both based their perceptions on certain behaviors of the other that they had observed over time. This made it so difficult for them to work together productively in a highly competitive environment that a member of the board was dispatched from European headquarters to the United States to mediate and bring the relationship back on track. Meanwhile, I had started to work with Rob, and I determined that it would be useful to conduct an assessment of both Rob’s and the CEO’s conflict management styles to see if a solution lay in that direction.

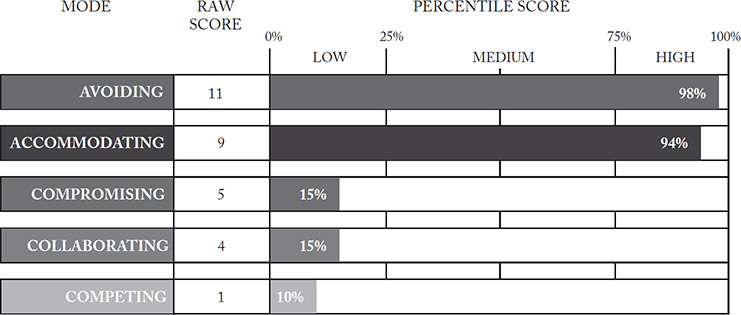

The results showed that Rob, the CFO, was off the charts high on the avoiding conflict management style, which would explain the CEO’s perception that Rob was disengaged and unwilling to provide input or engage in debate. Rob’s scores were almost equally high on accommodating—which meant that when he wasn’t avoiding; he was simply acquiescing to whatever the CEO and the rest of the leadership had decided. On collaborating and competing, Rob’s scores were as low as the other two were high, meaning he put little effort into working with the team to ferret out integrative solutions or vocally advocate for an idea he believed in (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Profile of TKI scores

The CEO’s conflict management styles? His competing score was exceptionally high, which, in light of Rob’s extremely low competing score, could explain why Rob felt that whenever he did offer his opinion to the CEO, he was brushed off or made to feel wrong. In turn, this behavior of the CEO may have reinforced Rob’s tendencies to conduct himself passively. Add the fact that, like Rob, the CEO had a relatively high score on avoiding, and it becomes clear why critical issues that needed resolving between them were simply left to fester.

A cautiously happy ending to this story was that both the CEO and Rob realized that each had contributed in his own way to their troubles, and both were willing—with my support as coach—to collaborate on holding each other accountable for more productive behaviors and conflict management styles.

Nine Powerful Ways to Resolve Conflict, Restore Harmony, and Strengthen Interpersonal Rapport

For business professionals who hope to positively impact their organizations while also building their executive presence, conflict can provide great opportunities to test their mettle and show enlightened leadership. The following list offers some additional tools and strategies to aid in that process.

1. Use active listening. Most of us understand the benefits of “being in the moment.” In a conflict situation, this means listening carefully to all sides without an emotional filter, the way a judge listens to lawyers pitching their cases. If you’re a manager arbitrating a conflict between two employees, this is a bit easier than if you are a party to the conflict. Nonetheless, being crystal clear on the reasoning of each side in a conflict is critical to helping create a mutually satisfying resolution. The term “listening” in this context applies to more than words; you should strive to perceive the multitude of signals—from vocal tonality to facial expressions and body language—all of which can speak volumes about the intent and motivation of the participants.

2. Acknowledge and validate. As an arbitrating manager, it is critical that you not only seek to understand both positions in a conflict but also validate each party’s claim. You don’t have to agree with the claim; just acknowledge each party’s unique perspective. This alone can open the parties’ minds with the assurance that they’ve been heard, even if the outcome doesn’t exactly go their way. People need respect and consideration just as much as they want to get their way. In the game of conflict, sometimes emerging emotionally validated, with one’s status intact, is enough.

3. Empathize. The power of empathy in conflict resolution cannot be overstated. Empathy happens when you put yourself, minus your biases and personal experiences, in the shoes (the circumstances) of both parties or, if you’re one of the combatants, in the shoes of your opponent. Try more than to just see the situation from the other person’s point of view; try to feel it, too. If you do, you may find that the picture takes on a slightly different hue.

4. Implement boundaries and expectations. Because you are a manager, people are looking to you to clarify boundaries and expectations for behavior and outcomes. If these things are muddy in the middle of a conflict, your job is to clarify them for the feuding parties. The idea here isn’t to reprimand but to prevent escalating emotions from clouding the established norms of conduct in a conflict and to reinforce the expectations for roles, behaviors, and outcomes. A good way to open this can of behavioral worms is to simply ask the parties to state what they believe the boundaries and expectations to be that pertain to debating the issue at hand, using their perspectives as a platform for your clarification and reinforcement. This approach enables open and honest communication and will keep the parties within acceptable boundaries as they (or you) work through the issues.

5. Be tactful. This may not be easy, as any one of the parties to a conflict may be way out of line from the outset. But don’t get sucked into the brewing emotion, and don’t convey even the slightest sense of disrespect for the parties or their views even if they originated on another planet. If you remain sensitive to their feelings, the chances that they’ll remain open to your input increase—to everyone’s benefit.

6. Explore alternatives. The parties to a conflict rarely are interested, at least at first, in looking at things differently. It’s your job as the arbitrating manager to help them do this, and it happens when you begin exploring alternative views and solutions with them. Ask open-ended questions such as “How would you act differently if this policy were reversed?” that require thought and elaboration. If you can get them to talk about an alternative, you’re a step closer to getting them to accept one.

7. Use “I” statements. When you are a party to a conflict, using a first-person context is much more productive than using other language. If you say, for example, “I was angry when you said that about me,” you’ll be greeted with more openness than you would be if you say, “What you said about me was wrong.” People can’t argue with how you felt, but they can certainly dispute the right or wrong of things. Speaking about how you feel avoids accusation, and accusations are fuel on the fire of conflict.

8. Make use of the power of stroking. It may sound manipulative, but if you can say something positive about the other person in the heat of a dispute, that person will be more open to hearing what you have to say about the issue at hand. Stroking the other person says you aren’t attacking her character and haven’t lost respect for her, only that in this instance you disagree with something that was said or done. Conflict goes off the rails when it becomes personal, but ironically, injecting something personal in a positive manner is the best way to keep it from going there.

9. Attack the issues, not the person. Conflicts sometimes are smoke from another fire or the surfacing of past disagreements or personality conflicts. When you sense triangulation entering the argument—the use of an unrelated opinion or issue to create a negative context for the present one, such as “You always put yourself first in these situations”—you know that this is personal rather than issue-driven. As an arbitrating manager, listen for anything that is personal in nature and bring the conversation back to the issue as quickly as possible.

How to Nurse a Strained Relationship Back to Health

No matter how enlightened your conflict management approach is, when emotions run high and egos get bruised, relationships can suffer long-term damage. And particularly in a work environment where cooperation and teamwork reign supreme, this isn’t something to shrug off. Fortunately, there are a few proactive ways to restore a relationship, or at least replace simmering resentment with mutual respect and collegiality

One key to healing a broken or strained relationship is to let go of any residual negative emotions that remain from the conflict. If you were one of the participants in the conflict, remember that holding a grudge certainly won’t add luster to your executive presence or elevate your status with your colleagues. Being generous, however, might. Drop the grudge, and you may find yourself empowered by doing so. (For managers with a bird’s-eye view of the conflict, it may be necessary to nudge the parties to repair the relationship if they are not sufficiently motivated on their own to do so.)

If you owe someone an apology, give it. If someone owes you an apology, make it easy for the person by extending an olive branch first. Show that you harbor no hard feelings and are willing to forgive (this is better shown than told). Asking for help or advice on something you’re working on or inviting the person for a cup of coffee can do the trick. If you have trouble forgiving and letting go of resentment or continue to evaluate that person in a negative light, seek different perspectives from trusted coworkers. You might even consult a mentor, especially if you feel your attitude is compromising your other relationships. The bigger man and woman win points here. (But don’t think of yourself as the “bigger” person. Instead, adopt humility as one of your new core leadership traits. It will serve you far beyond the context of conflict resolution and has shown to be a key predictor of business success among senior executives.)

One of the most powerful ways to heal a strained relationship is to go right at the problem. Be transparent, warm, and open-minded and find a place and time—again, lunch or a hot beverage can be a nice excuse for an occasion—to lay it all on the line, not with the intention to revisit the conflict in minutiae, but to mend the relationship. Looking forward, point out what you’ll do differently from now on (this is not the same as admitting fault), given the lessons you’ve learned in the process. Ask your colleague what he or she thinks it will take from both of you to make the relationship whole again. And then listen with empathy.

When the intention is to heal and move forward rather than to revisit the past, you’ll find the process easier than you expected.

In Chapter 9 we’ll look at how we can assert and reinforce executive presence and gain respect by managing difficult conversations: the conversations we’d rather not have but need to have in various situations for personal and professional success.