1

Rethinking Your Definition of Talent Mobility

In 2010, I was sitting at a relocation industry conference listening to people talk about the term “talent mobility.” I had just started my MBA at London Business School, fresh off working in finance, which had brought me from the United States to Asia to Europe. I couldn’t believe how cumbersome and frustrating it had been to move for work. So, as I started business school, I decided to take a closer look at the outdated relocation industry and how I could make it easier for families everywhere to move. This catapulted me into becoming an entrepreneur (like my mother, a small business owner of 47 years) and founding Topia, a relocation and HR software company that enables talent mobility for the Fortune 1000 and the employees who work there. Since then, Topia has helped tens of thousands of families move, created hundreds of jobs, and grown to global operations.

At that point, however, I knew virtually nothing about the nuts and bolts of corporate relocation or talent management or human resources. I had talked my way into a “consulting” role with the Forum for Expatriate Management, a horribly named but incredibly large corporate relocation conference group, where I figured I’d learn why things were so outdated and what kind of business was needed for the future. And that is how I found myself sitting in an ugly-carpeted hotel ballroom drinking stale coffee and listening to HR professionals talk about talent mobility.

The problem was that no one at the conference, and I later learned anywhere else, actually knew what talent mobility meant. For most people at the conference, it was a sexier label for corporate relocation, a way to jazz up a staid industry in the back-office of big companies. For others, it referred to people who moved between companies or jobs within companies—a sexier label for internal and external recruiting. For some, it referred to people whose jobs were displaced by automation and had to find another form of work. For still others, it meant employees who had mobile phones.

Nearly 10 years later, we still don’t have a good definition for talent mobility—even though talent mobility is defining us. Growing disruptions to the way we work and the jobs we do means that today more people move, for many more reasons, for many more durations, and in many more configurations. They move between countries. They move between cities. They move between jobs. They move between teams. They move between careers. They move between their home and office. They move between traditional employment and freelance work. My generation will work across more careers than our parents did companies.

I have spent most of the last decade in meetings discussing talent mobility and the future of jobs—with business leaders, government officials, industry analysts, investors, journalists, consultants, employees, and customers of Topia. In these discussions, we consistently talked about how unleashing talent mobility is the key to traditional companies transforming to win the war on global talent, creating new jobs that can be done anywhere and evolving jobs in the face of a changing economy. The problem, however, is that most of the world is still just as confused as the corporate relocation professionals were in 2010. We still don’t have a clear definition of talent mobility. And we don’t understand how it can be used to support businesses, workers, and families in the face of change.

It’s well known today that globalization, automation, and demographic change are upending the way we work. We have seen storied companies overtaken by upstart new competitors, the gig (or freelance) economy emerge to account for a growing share of jobs, escalating demand for job flexibility and autonomy from millennial workers, and communities decimated by globalization, automation, and unpredictable work. It’s less clear, however, what our companies and country should do in the face of these trends, which together have created the Talent Mobility Revolution. This book gives you the answer.

To succeed amid the Talent Mobility Revolution—in the future of jobs—companies must first know what talent mobility exactly means. In this first chapter, we provide an applicable definition of talent mobility that you can use as your guiding framework for transformation. From there, we can look at how business leaders can reinvent their companies, how workers can best be supported through change, and how government leaders must rethink policies to foster a new economy that benefits everyone.

Companies and managers that are stuck in the past with traditional definitions of business operations, human resources, and corporate relocation will fail in the twenty-first century. Success today comes from being a Flat, Fluid, and Fast Company (an F3 Company). Once you understand what talent mobility means today, you’ll understand how it impacts all parts of your business and talent strategy, and how to transform in the face of the seismic macro trends of globalization, automation, and demographic change.

The Traditional Company Lexicon

Human resources (HR) can be traced to the ideas of two men in the nineteenth century—Robert Owen, a Scottish social reformer, and Charles Babbage, a mechanical engineer. Although the term human resources did not emerge until later, these two men are generally regarded as the first to see that the well-being of workers made them more effective and productive for companies. The first formal human resources department is generally believed to have been the result of a large worker strike at the National Cash Register Company in 1901. After this strike, the company established a “personnel” department responsible for record keeping, workplace safety, wage management, and employee grievances—the world’s first HR department.*

Through the early twentieth century, with trade unions and personnel management departments growing, the traditional human resources discipline started to take hold. As employment legislation passed, including the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935 that protected certain rights of employees and employers, and companies grew larger and more complex, HR departments became responsible for ensuring companies were compliant with state and federal employment laws and that workers were protected. As HR evolved through the twentieth century, the discipline evolved to include traditional HR operations to manage employees, recruiting to hire employees, and corporate relocation to move employees. For decades, this is how HR was set up and defined.

How Traditional HR Departments Managed Employees

Traditional HR operations were responsible for exactly what the name said—managing the operations of the company’s human resources. Employees were considered resources that the company needed to manage to get work done. Traditional activities included paying their compensation, administering their benefits, conducting their annual performance reviews, and ensuring compliance with labor laws. Business leaders sometimes perceived traditional HR departments as a type of operational policeman—keeping companies out of trouble and ensuring people got pay, benefits, and performance reviews on time.

Topia’s first VP People, Rachael King, had an impressive career across companies like Cisco, Vodafone, and AXA before joining Topia in 2014. She remembers her early career as “operational HR,” with work largely done on files and paper. “When I started in HR, the jobs were transactional,” says King. “As my career has evolved, so has the HR discipline. I saw a more strategic side of HR gradually develop, and I became a greater partner to the business. But even as HR grew in strategic importance, we still had to knock down the door to business leaders to get them to take us seriously. Today, however, my role is increasingly seen as a true partner to the CEO, like at Topia.”

Peggy Smith is CEO of Worldwide ERC, a trade body that educates and connects more than 250,000 corporations, thought leaders, learners, and mobile people. She has had a front-row seat to the evolution of HR operations across her member companies.

“Over the last 10 years, I’ve seen a retooling of the broader HR function from tactical (compliance, annual reviews, offer letters, etc.) to strategic (workforce and succession planning, critical skill deployment, and the like). Companies now recognize that talent is not a resource to be managed, but a critical asset to business success,” says Smith. “HR functions are now expected to have the business acumen to both manage talent and drive the results needed.”

How Traditional HR Departments Hired Employees

As companies grew and needed to hire workers more regularly, the recruiting function became an important part of the traditional HR department. The purpose of the recruiting department was to source candidates for open full-time roles, convince them that they should join the company, and complete the hiring process. In nearly all cases, recruiting was done with external candidates in the relevant local market, often in partnership with external recruiters who maintained a database of candidates. Company recruiters would schedule and conduct interviews, negotiate compensation and benefits, and execute offer letters with the selected candidate. Over time, graduate recruiting programs sprung up where recruiters would go to college campuses to source and interview candidates for entry-level roles, often as a part of a broader graduate program. Other than campus recruiting programs, it was rare to source candidates from afar. Recruiting focused on local hiring for full-time roles for jobs done in an office.

How Traditional HR Teams Moved Employees

Corporate relocation departments came about when an employee needed to move to a new office location, generally the result of international expansion of the company or some type of knowledge transfer or training that was required in a different market. Generally, about 3 to 5 percent of staff moved like this each year. In these circumstances, a manager asked an employee to relocate, and after the employee said yes, he or she interacted with the corporate relocation department, a part of the broader HR organization, to manage the details of the move. These moves were generally either full relocations, a permanent move to a new location, or expatriate assignments, a three-to-five-year engagement where the employee and family would relocate and then return back home. Packages were full of benefits—housing, cars, school support, tax, and immigration support, etc.—to entice families to relocate or accept assignments and carry out work that the company needed done. The corporate relocation department was the back-office function that made all of this happen—with no hiccups for the employee or with local laws. No one really thought much about corporate relocation beyond this.

In 2006, I joined Lehman Brothers as an investment banker after college and interacted with these very departments—HR, recruiting, and corporate relocation. After learning Mandarin and studying China in depth in college, I talked my way into an investment banking job in Hong Kong instead of the traditional analyst program starting in New York. After accepting the offer, I was handed over to the corporate relocation team to process my relocation from the United States to Hong Kong—sending them into a tailspin since I didn’t fit the model of an existing employee relocating at the request of the company. A year later, bored with writing pitch decks in a cubicle in Hong Kong, I again talked my way into an opportunity to long-distance commute to India to work on the country’s largest initial public offering at the time. Again, falling outside of the definition of traditional corporate relocation, the bank didn’t know how to handle me. Instead I got a travel visa and hotel room for nearly a year, and I crossed my fingers every time I entered the country that I wouldn’t be stopped at the border for spending so much time working in India. With these experiences—and similar ones I saw my colleagues and friends starting to have—I knew that the traditional definition of corporate relocation was changing. I knew that I was witnessing a systemic shift in the way we work, and that companies would have to adapt.

“Corporate relocation has historically been a caretaker-oriented, operational role for a small portion of relocations and expatriate assignments, largely for mid- and senior-level employees. There was a heavy focus on ensuring all went smoothly regarding compliance, and that the employee could get from point A to B and start work as quickly as possible,” says Peggy Smith. “But now corporate relocation has evolved to be just one part of a much broader definition of talent mobility that is at the heart of today’s successful economy, job creation, and company operations.”

The Building Blocks of Talent Mobility Today

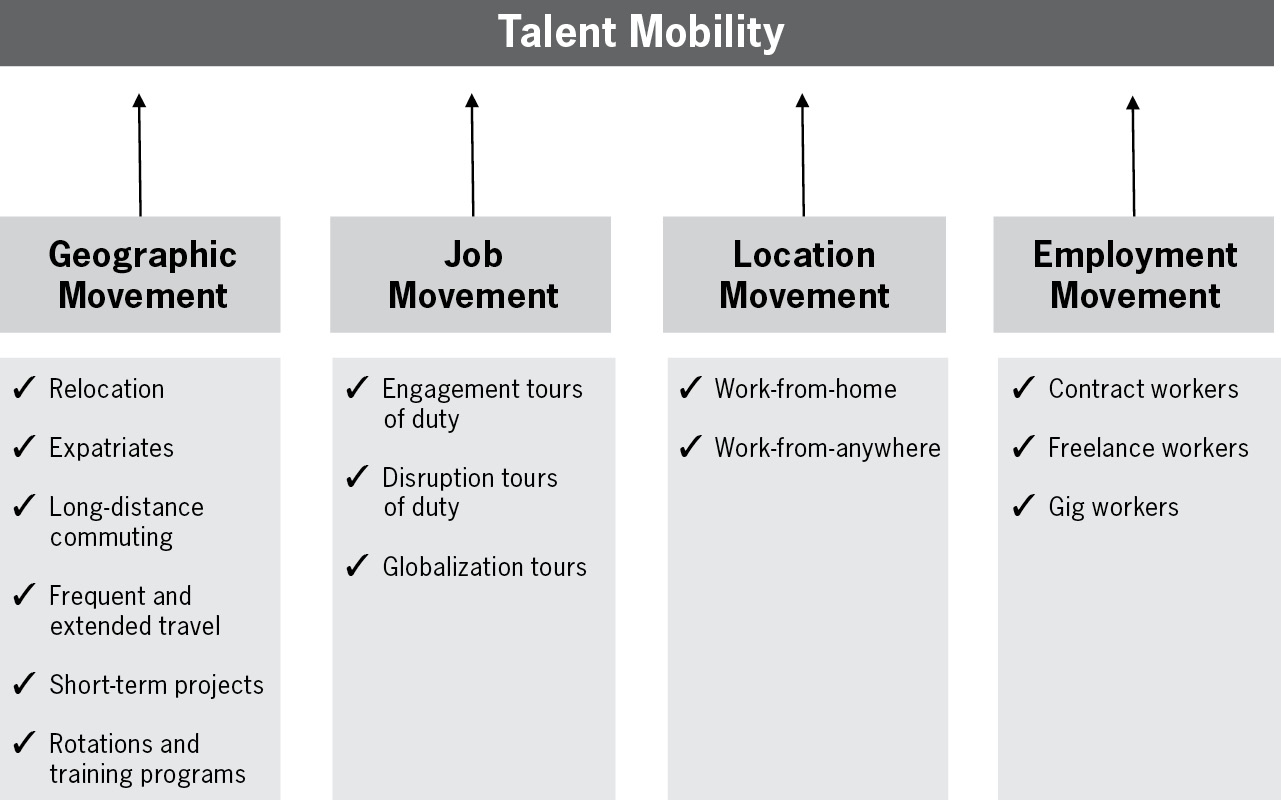

With the forces of globalization, demographic change, and automation, we are seeing a fundamental shift in the nature of the HR department. F3 Companies now recognize that talent mobility—and the ability to leverage employee movement to drive employee engagement, accelerate innovation, and unleash growth—gives them a competitive advantage. The way they think about their workforce, strategy, and operations must be redefined with talent mobility at their core. To tap into the Talent Mobility Revolution, F3 Companies transform from running traditional HR departments to putting talent mobility at the core of their whole business to unlock work from everywhere. This transformation starts with defining what talent mobility means. Talent mobility is the movement of employees across geographies, jobs, locations, and employment classifications. We discuss each of these four building blocks of talent mobility in this chapter—and then how they influence different parts of your business in subsequent chapters.

Geographic Movement

Employees today move geographically more than ever. But these moves are not only the traditional relocations and assignments of yesteryear that you’re probably thinking of. (In fact, traditional relocations are waning in the United States.) Rather, when we say moves, we mean many different configurations of geographic movement from commuting to short-term projects to frequent travel. Workers today move for an ever-greater set of reasons and depend on frictionless geographic mobility for training programs, career progression, continued engagement, lifestyle, fulfillment, salary, family needs, and much more. Increasingly, this geographic movement doesn’t only come from companies asking employees to move to fulfill a business need, but from employees raising their hands for personal reasons, and growth and learning to fulfill their own career ambitions.

In our definition of talent mobility, geographic movement includes six configurations:

• Relocations. The traditional one-way permanent move

• Expatriate assignment. The traditional three-to-five-year move with a return home

• Long-distance commute. Regular work across two locations with travel between them (e.g., working every other week between Sacramento and San Diego)

• Frequent travel (aka, the road warrior). Regular work across many locations with travel in between them

• Short-term projects. Structured fixed-term work in a given location

• Rotation and training programs. Structured fixed-term work in multiple locations

Since founding Topia in 2010, I have seen this evolution happen firsthand. When I founded the company, most of the businesses I spoke to had a traditional corporate relocation department responsible only for relocations and expatriate assignments. Today, Topia’s most innovative customers now define geographic mobility to include all of the major configurations of geographic mobility—and many of them have rebranded their corporate relocation departments as talent mobility departments. These companies use long-distance recruiting to fill talent needs, host training programs for workers around the world, regularly deploy people to open new markets or conduct short-term projects in different places, embrace commuting and frequent travel as a way to balance employees’ work and personal needs, and hire people who live outside of traditional urban hubs.

Each year at Topia, we host Customer Advisory Board meetings where we bring together our customers to discuss upcoming product developments and hear their feedback. Almost always these conversations include discussions about the many more ways employees are moving today, and the complexity this brings to the talent mobility teams who have to manage it. I recall discussions about frequent travel across states and countries, which kicked off tax challenges, and high performers who wanted to move to other locations and commute to their jobs—should the company allow this? And how could the company do this if it had no entity in the location where the employee wanted to live? The general consensus in all these conversations was that employees today move for many reasons and in many ways—all of which should be included and managed under one talent mobility umbrella.

Eric Halverson joined eBay 15 years ago to build its talent mobility program. Over that time, he has led the transformation of eBay’s geographic movement from a small number of domestic relocations and expatriate assignments to frequent geographic mobility—including sharp growth in short-term project moves, rotational and training programs, commuting, and frequent business travel in recent years. Today, a large portion of the company falls into the frequent business traveler classification.

Halverson started this transformation by reviewing with HR leadership and specific business unit leaders throughout the company the changing demographics of employees and their preferences for greater geographic mobility—and the different and more frequent configurations it would entail. He educated the company on how opportunities for geographic movement could be leveraged as a part of recruiting, developing, and retaining top talent, particularly in the fierce talent wars between top technology companies. Halverson created frameworks to enable employees to work across different locations and scenarios, including business-directed geographic movement and self-initiated geographic movement—like we discussed at the Customer Advisory Board meetings.

The result is that, as Halverson says, “eBay now recognizes that this is how employees today work and it helps us to attract and retain the talent we need—in a very competitive recruiting environment. Geographic movement, coupled with flexible remote work scenarios, is a key pillar of both our business and talent strategy.”

“Today, there is an expectation that work is frictionless,” says Nick Pond, who leads EY’s People Advisory and Consulting services, advising the world’s largest companies on their talent mobility strategies. “People see movement as part of their career learning, experiences, and life. We are seeing a huge increase in geographic movement across our global clients, particularly in frequent short-term moves and extended business travel, which allow employees to get work experience in different places while balancing personal and family needs.”*

Job Movement

Underlying all of this geographic movement is a stark increase in employees moving between jobs within companies. Today, an employee may start her career as a customer service rep, then move to a sales role, before working for some time in marketing, before becoming a project manager. Much of today’s workforce watched the promise of a job for life erode for their parents amid the 2008 recession. This recession threw away the long-held social contract where workers traded autonomy and flexibility for the stability and benefits that came from a traditional job. Today’s generation of workers are realistic about disruptions that may occur to their jobs, and may instead seek autonomy, flexibility, and continuous learning in their careers. They want to build a tool kit of skills that they can leverage across different opportunities throughout their career. Workers often now look at their careers as a series of different job segments, or tours of duty, a phrase coined by LinkedIn Co-Founder Reid Hoffman, with Chris Yeh and Ben Casnocha, in their 2014 book, The Alliance. Employees today expect to have many career segments rather than a “job for life.”

With disruptions to jobs more frequent and employees demanding tours of duty, job movement is on the rise within companies. Facilitating it is an increasingly important part of attracting and engaging top talent, and having the agility to respond to opportunities and disruptions that arise for your company. To do so, companies must rethink how they structure and staff work, something we’ll discuss in detail in Section 2.

Job movement includes three types of tours of duty:

• Engagement tour of duty. An employee who is disengaged with a current job and requests a new job. Companies that don’t make this happen often lose employees to another company or to work in the freelance economy.

• Disruption tour of duty. An employee whose job has been disrupted or made obsolete, often as the result of automation. These employees now can be moved to a new job, and must be supported well through the transition. Companies that don’t make this happen lose institutional and cultural knowledge.

• Geographic tour of duty. An employee who is moved to a new job to gain experience in a new market or fill a business need there. Companies that don’t make this happen often lose out to their more agile competitors.

Kerwin Guillermo leads HP’s Global Talent Mobility function and has transformed the traditional corporate relocation function to include dynamic job movement. Guillermo first joined HP as a part of the Talent Acquisition team Asia, which also included traditional corporate relocation in the region. He progressed through the organization to eventually lead Global Talent Mobility, where he set off to transform the way HP thought about talent mobility, and bring more dynamic job movement into the company’s traditional definition.

Fresh off reading Simon Sinek’s book, Start with Why, Guillermo says he approached his new role by thinking hard about “the why of mobility—both in terms of how it achieves company objectives and each employee’s objectives, particularly for millennial employees.” He knew that it would be difficult to align a large, complex, global company like HP around a new definition of talent mobility, so he set out to rapidly show value to business leaders through increasing job movement.

Guillermo knew that HP’s business and staffing leaders traditionally looked to local hiring to fill new jobs. He thought that if he could show that talent mobility can offer diverse talent and business solutions to rapidly fill jobs and skills needs with internal talent, the company would start to think about job movement—and tours of duty—as a key part of its talent mobility definition and business strategy. Similarly, he knew that HP employees were increasingly looking for tours of duty as a part of their careers. Including job movement in the traditional talent mobility definition would help attract, retain, and engage the talent the company needed to succeed.

Guillermo cites examples of matching employees with emerging skills, like artificial intelligence, data science, or cybersecurity with jobs across the company, and where employees from “mature skill markets,” like the United States and United Kingdom, were matched to tours of duty in “growing skill markets” like China or the Czech Republic.

“My first success in clarifying the definition and perceived value of talent mobility was quickly filling ‘difficult-to-fill’ jobs that were revenue-generating and would previously go unfilled for over 120 days with traditional local recruiting processes. Filling that vacancy could be directly attributed to revenue generation, showing the clear benefit of talent mobility,” says Guillermo.

“These real experiences, that benefited the business, really expanded people’s understanding that talent mobility is not just corporate relocation anymore. It is about dynamically matching people with skills to jobs that need those skills. By doing this, we were also responding to our employees’ increasing demands for more career phases and skills development.”*

Robert Horsley is both the Executive Director of Fragomen, the world’s largest private immigration firm, and the Chairman Emeritus of Worldwide ERC, the trade body where Peggy Smith is CEO. Through these roles, he sees growing job movement at companies like HP.

“I am seeing work happening in smaller segments that build on themselves,” says Horsley. “We can think of this as a modularization of the workforce, similar to what we’ve known as the traditional internship. These ‘modules’ happen in one place with one team, and then they end, and a new one starts, often in a different place, with a different team, not unlike the nonlinear way a film is made. This is a new iteration of job movement, and should be part of our definition of talent mobility.”*

Location Movement

In addition to growing geographic and job movement, work today has a growing amount of flexible and remote (or distributed) work. Companies eager to reduce costs and carbon footprint and to support employees with flexibility and work-life balance embrace flexible work arrangements as an important part of their business and talent strategy. Location movement, or remote and flexible work, is the third building block of talent mobility.

Many companies, however, don’t yet define or manage location movement in a cohesive manner. Rather location movement often emerges as a series of one-off allowances managed haphazardly across the different business areas. With growth in distributed work comes the need to manage employee collaboration and compliance, plus new opportunities to hire from a larger talent pool. Location movement must be a deliberate part of talent mobility definition and strategy.

Location movement includes two types of distributed work:

• Work-from-home. Full- or part-time work done from a home office

• Work-from-anywhere. Full- or part-time work done from outside the company office, including in coworking spaces, cafés, and while traveling

Companies like Automattic, which owns popular content management platform WordPress.com, have made remote work a key part of their business strategy and employee value proposition. Automattic has 877 employees across 68 countries, all of whom work remotely. At Automattic, employees can truly work from anywhere: a home office, a beach, or a local café or coworking space. (The company even provides an “office stipend” for those who prefer to work around others and leverage a local coworking space.)* Similarly, companies like HP, where Kerwin Guillermo leads talent mobility, have moved away from “office face time” to partial work-from-home models, where staff comes into the office to collaborate or work on specific projects using “hot desks” in the office. Like employees moving between geographies, these employees are moving—from external work locations to an internal office location—and this should be included as part of the talent mobility definition and managed as part of one cohesive strategy.

From 2016 to 2018, Jing Liao was the Chief Human Resources Officer for rapidly growing Silicon Valley lending company SoFi, where she saw a surge in employees asking to work-from-anywhere—a frequent request from today’s millennial staff.

“Every week, I have employees coming into my office and asking to move to some location and work from there,” said Liao at the Bay Area Mobility Management Conference. She then went on to cite a recent example where a high potential engineer wanted to spend some time exploring Mexico while still working at SoFi, and she had to figure out how to make this work.

“As a company, we need to make this happen, or we will lose our talent to our competitors. It’s very difficult to manage, but it’s critical for our success—and the success of so many other companies—with today’s millennial workforce,” said Liao.*

Stephane Kasriel, CEO of NASDAQ-listed company Upwork, the world’s largest freelancer platform, says that nearly two-thirds of companies (63 percent) now have full-time employees who work outside the office.† Upwork, like Automattic, lives this—it has about 400 people who work from a company office and about 1,000 who work remotely.‡ “Companies that refuse to properly support a remote workforce risk losing their best people and turning away tomorrow’s top talent,” says Kasriel.

Employment Movement

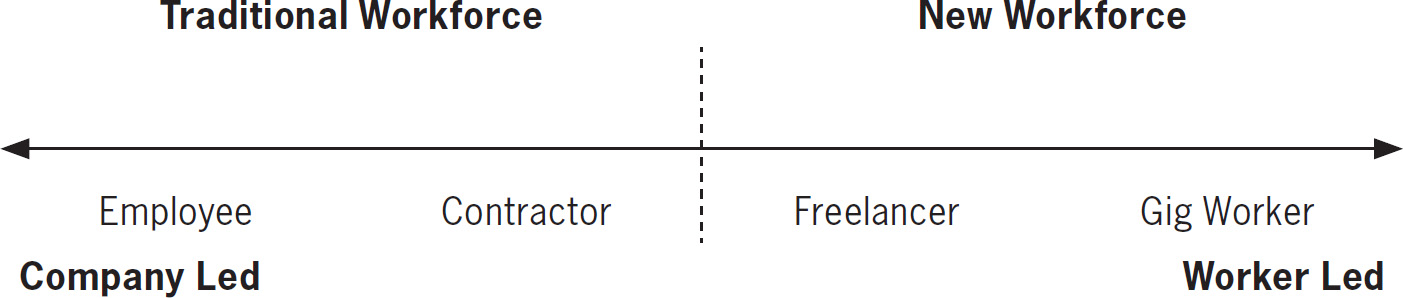

The rise of the freelance or gig workforce has created a fourth type of movement for our talent mobility definition: employment movement. Companies today increasingly have a workforce that includes both traditional full-time employees (FTEs) and freelancers—workers who contribute their skills on demand for a particular job, project, or team as microentrepreneurs. Companies have historically used contractors for specific fixed-term work, but today staffing models are evolving to include dynamic skills matching with teams regularly made up of FTEs and freelancers. Similarly, workers increasingly look at their careers as having both full-time work and freelance gigs—a given worker may work as an FTE at one company and freelance across gigs at the same time, or may have different career segments moving between full-time work and freelance gig work. The definition of talent mobility should include managing an expanded definition of the workforce and workers’ movement between classifications.

Employment movement includes four classifications of workers and their movement:

• Employees (FTEs). Workers hired full-time with traditional employment benefits, protections, and contract provisions.

• Contractors. Workers hired for specific, fixed-term work with particular requirements for the amount of work that can be done so as to not classify workers as FTEs. Often called a 1099 worker in the United States to signify the tax treatment (workers’ income is reported to the IRS on Form 1099) and independent nature of the work.

• Freelancers. Workers hired to complete high-value, specific work (e.g., engineering or design). Often freelance workers are hired on demand when their skills are needed, and frequently they work remotely.

• Gig workers. Workers hired to complete work that is short and simple in nature (e.g., a delivery or translation of a specific document). Often gig workers are hired on demand when needed, and frequently they work remotely, augmenting their principal income.

These four classifications of workers are reinventing the way companies define their workforce and manage movement between types of work. This has also spurred a vigorous debate among policy makers in the United States about employment benefits, protections, and tax treatment for this growing cohort of freelance workers, and whether a new worker classification is needed under federal labor law (see Chapter 10 for a full discussion of this).

Today’s workforce can now be defined as including both a traditional workforce and a new workforce:

Stella and Dot is a company that was founded with employment movement and an expanded definition of the workforce at its core. The company has both full-time employees and contract workers as a part of its business model. Stella and Dot sells jewelry, bags, and other accessories both directly on its website and through a large group of social sellers, freelance microentrepreneurs that manage their own independent businesses selling Stella and Dot’s products. It’s common for FTEs to also work as sellers—both working full-time at the company and independently as members of the freelance economy. Stella and Dot thinks of the company’s workforce as including both its FTEs and freelance workers and regularly brings together its top sellers to interact with FTEs, something we’ll discuss in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Like at Stella and Dot, one of the principles of employment movement is flexibility—workers have the choice to use their skills when they want to, whether as independent microentrepreneurs in the freelance economy or as a part of a team at a Fortune 500 company.

“For large, traditional companies to survive digital transformation [and disruptions], we must rethink their talent models.” says Stephane Kasriel. “Innovative companies adopt more agile approaches to sourcing talent—often finding skills they need online among a growing workforce of independent professionals.” According to Upwork, 9 out of 10 hiring managers said they were open to working with freelancers in 2018.*

“We must use an expanded definition of the workforce, and tie flexibility and learning into today’s employment model,” says Peggy Smith. “Employees increasingly are choosing what type of work they want to have—whether full-time, working as a part of the freelance economy or taking a career break for an adventure, or to volunteer somewhere. Throughout all of this what you’re seeing is people placing a greater value on skills development and their time. My generation was about money and stability. This one is about time and experiences. This is why I see the full employment model as under attack, and why employment movement and different staffing models are such an important part of talent mobility.”

The New Lexicon of Talent Mobility

The Talent Mobility Revolution is driven by the forces of globalization, automation, and demographic change. Talent mobility should be defined as all types of employee movement across geographies, jobs, locations, and employment classifications. Unlocking this helps companies win the war on talent and create business agility, ensuring they can respond to disruptions and opportunities as they hit.

However, just like in 2010 at the relocation conference, there remains significant confusion about how to bring these four building blocks together into a single definition of talent mobility that can underpin a new business and talent strategy. While building Topia, I met with countless investors, analysts, and customers who looked at me with blank stares when I talked about talent mobility. They asked me if I actually meant recruiting, movement between companies. Or if I meant relocation. Or meant the growing amount of remote and virtual work. Actually, I’d say, these are all part of talent mobility—and this is the future of your company.

Today, I still ask company leaders and managers I meet how they define talent mobility. The most forward-looking companies have evolved to include geographic, job, and employment mobility under their talent mobility definition, but few have brought all four building blocks together to harness the new workforce in an intentional and efficient way.

The definition of talent mobility today must include geographic, job, location, and employment mobility. Put together, it should look like this:

Companies—from pharmaceutical manufacturers to investment banks to technology companies like HP, are taking steps to define talent mobility like the blueprint in the figure. In 2018, I was speaking about the Talent Mobility Revolution, and the new definition of talent mobility, at a conference when the Head of Talent Mobility at a Fortune 500 financial services company approached me. She told me that her company was taking steps to do exactly what I was talking about—bring together the various forms of employee movement into a single talent mobility area, and she had recently been appointed to lead this initiative. Another Topia customer—a global bank—started to redefine talent mobility and reorganize around it in 2017. The firm had appointed a new head of human resources, who was not from a traditional HR background. Upon taking his new role, he had reorganized around talent mobility, uniting geographic, job, and employment movement under a single umbrella, now defined as talent mobility. With this updated definition and reorganization, I had been called to discuss the operations and systems to manage this new talent mobility area, something we’ll cover in Section 3.

Peggy Smith regularly advises companies on talent mobility transformation, as part of her role as CEO of Worldwide ERC. She believes we are just at the beginning of this transformation, however.

“The definition of talent mobility is being rewritten,” says Smith. “Movement doesn’t need to mean crossing a state or regional border, as ‘corporate relocation’ historically did. I worry that most companies and leaders still only understand talent mobility with a physical manifestation. But today, talent mobility includes all types of mobile talent—virtual and remote work, contingent workers, frequent travelers and commuters, short-term moves for tours of duty or projects, or new jobs internally at the company, and relocations and expatriate assignments.

Smith continues, “Talent mobility means you’re able to move people resources in and out as you need them, whether physical or virtual, full-time or contingent.”

Some might say it’s the human equivalent of scalability. This talent mobility revolution isn’t exclusive to crossing a border. Companies must transform along these lines to be positioned for the future. Not many have figured out how to do this yet—especially larger companies—but it’s coming, and that’s what many of my conversations with employers are about these days.”

This Talent Mobility Revolution is what I saw starting more than a decade ago at Lehman Brothers, and what made me found and build Topia. What I also saw was that the vast majority of companies were not ready for this revolution, and instead risked being left behind by more nimble and agile competitors. Most companies hadn’t even recognized this revolution was happening, let alone defined talent mobility and its components. Many still haven’t.

Defining talent mobility is the first step to succeeding amid the Talent Mobility Revolution. But the vast majority of companies haven’t even done this first step. Any business leader who wants to survive in the next 10 years must become an expert at talent mobility and leverage it for strategic advantage.

_____________________________

* Fast Company, “Welcome to the New Era of Human Resources,” May 20, 2015,https://www.fastcompany.com/3045829/welcome-to-the-new-era-of-human-resources.

* Interview with Nick Pond, Partner, EY People Advisory, December 17, 2018.

* Interview with Kerwin Guillermo, VP Talent Mobility, December 27, 2018.

* Interview with Robert Horsley, Executive Director, Fragomen, December 6, 2018.

* Interview with Catherine Stewart, CBO at Automattic.

* Discussion on a panel at 2017 Bay Area Mobility Management Conference.

† Upwork, Future Workforce Report, 2018.

‡ Interview with Stephane Kasriel, CEO, Upwork, December 4, 2018.

* https://www.upwork.com/press/2018/02/06/fortune-500-enterprises/.