9

Transforming Systems and Operations for Talent Mobility

When Susanna Warner went to Schneider Electric to lead its global mobility department, she knew that the HR transformation already underway posed one of the most complex global mobility challenges that she had faced in her career. Warner, however, brought a unique background to the leading energy management company. She had worked in talent management, international mobility, and compliance, so she brought both a strategic and operational lens to the job. Her mandate was to set up talent mobility for the future—and in doing so support the global power company’s international business footprint and recruiting of top talent.

In order to support the HR transformation, Warner included with the policy review already underway (as discussed in Chapter 7) a three-year transformation plan with one major theme each year. Her next two years focused on digitizing systems and enhancing the employee experience amid a talent mobility world. In parallel, Schneider Electric initiated transformation to link geographic mobility with job mobility, launching a talent marketplace, as we also discussed in prior chapters. As she drove the changes in policies, systems, and operations, Schneider Electric itself was moving to an increasingly distributed work model, introducing further need to unify all of the parts of talent mobility in the digitization roadmap.

The goal of Warner’s digitization phase was to unify talent mobility systems and operations in modern digital systems, first looking at geographic movement to ensure she knew where all her mobile employees were at a given point in time so that she could manage tax and immigration compliance and geopolitical risk. After this, the mobility team started to focus on the “consumer facing” experience for geographically mobile employees—the systems, vendors, and partners that employees engaged with to manage their relocations, travel, and virtual work experiences.

Warner’s team started with more than 50 Microsoft Access databases that the HR team used to manage employees who were geographically mobile. This meant that Schneider Electric, a company of 144,000 employees, was largely managing its mobile talent from spreadsheets, and entirely separately from the other company systems, such as core HR, payroll, and finance, and external vendors, such as compensation providers, real estate firms, and immigration providers. The team started thinking about how to unite the more innovative systems like relocation experience applications, a talent marketplace for job matching, and employee collaboration software. The team had to first digitize the nuts and bolts of geographic movement to ensure that all the basics could actually be managed within the frameworks of the company’s operations and global legislation. This required implementing a global mobility management (GMM) system to replace the databases.

We worked with Schneider Electric’s global mobility team as they implemented Topia’s global mobility management (GMM) system to digitize these nuts and bolts of geographic mobility. Their journey is not unique. Over my nine years leading Topia, I saw countless companies like Schneider Electric start the journey to transform their systems and operations for the Talent Mobility Revolution, often starting with implementing a GMM system. Like Schneider Electric, many of them were large, venerable, international, publicly listed brands that had been operating as traditional companies for decades. They started these transformations because they knew that, in order to succeed in the twenty-first century, they needed to make talent mobility the basis of their business and talent strategies. To do this, they had to transform their operations to make it happen. They realized that companies that could execute this transformation successfully would succeed in the twenty-first century and continue to win the global war on talent; those that didn’t recognize the need, or succeed in execution, would lose out to their more agile, innovative competitors.

While many business leaders recognize the forces of the Talent Mobility Revolution—globalization and automation—few know how to practically implement the operations and systems to make the talent mobility transformation we’ve discussed in this book happen. This is particularly acute because much of the world’s legislation—across employment, tax, and immigration law—was set up for the traditional way of working. At the same time, increasing geopolitical uncertainty and security threats make the reality of managing talent mobility more complex than ever.

With these forces all converging, companies need a clear operational and systems roadmap to harness the talent mobility revolution for success. This chapter shares how to set up systems and operations to harness the Talent Mobility Revolution to drive employee engagement, accelerate innovation, and unleash growth. It is the final puzzle piece to transforming into an F3 Company.

How to Employ People and Get Them Paid

The Traditional Employment and Pay Model

Traditionally, employees were employed by one entity with their payroll running from that entity. As we’ve discussed in prior chapters, talent mobility across locations, jobs, and employment was rare; however, a small portion of employees did move geographically for expatriate assignments or relocations. One of the main differences between these two policies was the entity that the employee was employed by: expatriates stayed employed by the entity in their home country; relocations moved to be employed by the entity in the host country. The entity that the employee was employed by then dictated where the employee’s payroll was run and in what currency. So, if relocating employees moved to a new entity in the host country, they were set up on the new local payroll and received their paychecks from there in the new local currency. If an employee instead moved as an expatriate, she would remain an employee of the home entity and have a payroll processed from there in that currency. Certain expatriates also received a split payroll, a portion paid by their home country payroll and a portion by their host country so they could cover local living expenses.

Lehman Brothers, as we’ve discussed in prior chapters, was a traditional company with traditional geographic mobility operations. When I relocated to Hong Kong for a permanent relocation, I became an employee of the Hong Kong entity and received my paychecks in local Hong Kong dollars. When I spent multiple months working on a project in India, but not relocating there, I continued to be paid by the Hong Kong entity in Hong Kong dollars. When colleagues moved from New York to Hong Kong for one-year expatriate assignments, they continued to be paid in US dollars from the US entity.

Entity and Employment Strategy for Talent Mobility

The overarching assumption in the traditional employment and pay model was that employees worked in geographies where the company had an entity and operating presence, whether as local employees or expatriates, and they were employed and paid from one of these entities. In the talent mobility era, however, this is changing. The continuous movement of the talent mobility era challenges the assumption that every worker will be working from a location where the company has a local entity and payroll operation. With frequent geographic and job mobility, and work-from-everywhere and work-from-home models, employees increasingly demand the flexibility to work where they want to even if a company doesn’t have an entity there. At the same time, freelancers with nontraditional payroll structures are becoming a greater portion of the workforce.

All of this introduces operational complexity for companies today. Current US employment law classifies workers as employees (W2 workers) or contractors (1099 workers). Employees must be hired by an entity, set up on the company’s payroll, and receive the corresponding employee benefits and protections, as we discussed in Chapter 8. Contractors must fall under certain requirements for hours worked for a single company so as not to be classified as employees. When contractors work for a sustained period of time from a location where a company does not have an entity, there can be a risk that they are deemed to be employees and create a “permanent establishment” in that market. Then the company is required to pay local taxes and classify workers as employees.

As discussed in Chapter 1, conversations on entity and employment strategies for talent mobility and the growing work-from-everywhere structure was a constant point of discussion over the years at our Customer Advisory Board meetings at Topia. Talent mobility leaders are accountable for managing the risk and operations of employee movement. Business leaders often say yes to work-from-everywhere models—in a drive to attract, retain, or engage key employees—without understanding the operational complexity it introduces. I have heard stories of talent mobility leaders reviewing company messaging channels to identify anyone who may be working somewhere that introduces company risks, fighting with business leaders about their decisions, and scrambling to set up entities to avoid tax exposure.

Forward-thinking companies know that employees will be continuously mobile, and they intentionally design a multitiered entity and employment model to support this. It should look like this:

• Contractor/freelancer employment. In this model, workers are hired as contractors, not full-time employees, and companies do not bear responsibility for benefits or taxes. The worker bears all risk for local tax payments and generally signs a contract detailing that he is not an employee and bears any and all employment liability. This model should be used when hiring workers as freelancers on project teams, for contracted part or fixed-term work on project teams, or when a company does not have an entity or permanent establishment (PE) in a given market. (Although beyond the scope of this book, it’s important to note that contractor status can be abused to take advantage of workers, leaving them with unpredictable hours, low wages and no benefits, and the company with higher profits. This is a big issue for the working and middle class in America today, and must be rectified.)

• Professional employer organizations (PEOs). A PEO is a local organization that employs and pays local workers on a company’s behalf. Workers are not formally employed by the company but are able to get the local benefits as employees of the PEO. Often companies treat their PEO workers as if they were full-time employees and also expand the benefits provided to be in line with their traditional employment benefits. It’s common for companies to transition contractors to a PEO model if they work with the company for an extended duration or in a largely full-time capacity creating employment risk. The PEO employment model mitigates employment and tax risk for companies and outsources operations and administrations to local experts.

• Employment by entity. When a company has a critical mass of workers in a given market and/or workers it wants to hire as full-time employees, it generally sets up a local entity that employees can be hired from. In this traditional model, employees are classified as full-time local employees. The best practice is for companies to tie their entity expansion to hiring a critical mass of workers in a given market.

• Employment by global employment company (GEC). Certain companies use global employment companies to employ employees who are continuously geographically mobile and reduce the associated operational friction. This model has been historically used by energy companies for their “career expats” and may grow common again in the talent mobility era as we discussed in Chapter 8.

Automattic employees can elect to work from wherever they want—from a rural hometown to a bustling urban metropolis to a remote emerging market. As you would expect, Automattic has a number of entities around the world through which employees are hired and paid. However, it also frequently has workers who want to work in markets where Automattic doesn’t yet have entities, so it hires these workers as contractors, but culturally engages them as if they were employees. Managers include them in project teams and don’t discuss or differentiate internally between their full-time employees and contractors—very much embodying the tenants of an F3 Company. When Automattic reaches a critical mass of freelancers in a given location—for example if numerous workers decide they want to live and work from Mexico—it considers establishing an entity and hiring them as full-time employees of the Mexican entity.

“Distributed teams expose you to different regulatory risk,” says Chief Business Officer Catherine Stewart. “It’s important to keep in mind local employment and tax policies.”

We found a similar challenge at Topia. When we acquired Teleport in 2017, its distributed team structure meant that there were a number of employees working as freelancers from locations around the world. Similarly, as we expanded our sales footprint into new markets, such as Germany and Australia, we found that the overhead of setting up an entity often did not make sense. Like Automattic, we pursued a multitiered employment strategy hiring freelancers to contribute to teams part-time, using PEOs to hire team members in markets where we did not have an entity but needed to hire staff and setting up entities once markets justified a permanent presence.

“The employment model that we follow at Topia with contractors, PEOs, and employees is the best practice for employment in the talent mobility era,” says Jacky Cohen, who leads Topia’s People and Culture team. “Outside of a PEO, today there is really no other way of hiring people in markets where you don’t have an entity, while having the confidence of being compliant and giving the best employee experience.”

Payroll Setup for Talent Mobility

Traditionally, payroll systems were set up in each market where a company operated and used to pay salaries and withhold local taxes. Amid the Talent Mobility Revolution, companies will have a diverse set of entities and workers that includes employees, contractors, and PEO-employed staff. In addition to this, employees will move frequently between entities and payroll systems as they work across geographies, jobs, and locations. Companies should follow the guidelines below for paying their different classifications of workers:

• Paying contractors and freelancers. Freelancers may be hired directly or through traditional staffing agencies. When hired directly, companies pay their project fees in an agreed-upon gross amount. The worker then bears responsibility for paying taxes. Therefore, the company does not need a local payroll system to administer these payments. Freelancers hired through staffing agencies may be paid by the agency, which then bills the company. Similar to this model, modern freelancer marketplaces like Upwork also now offer payroll management services, where they essentially act as a PEO for freelancers and pay salaries, and bill the company.

• Paying via PEO. When workers are employed by a PEO, the PEO is responsible for processing the local payroll, handling withholding taxes, and administering statutory local benefits. The PEO then bills the company regularly for these costs and the PEO’s services fees.

• Paying employees. Employees are paid through local payroll systems, which also process the local taxes. When employees move geographically, they may be transferred to a new local payroll, continue to be paid from the home country payroll, or have a hybrid setup where part of their paycheck is paid to them in the currency of their home office and part is paid in the currency of their new location. Because payroll systems are generally locally run, it’s important for all local payroll systems to be linked to the central global mobility system to ensure equalization and other benefits are calculated and withheld correctly. (See the following sections for an overview of the systems roadmap to enable talent mobility.)

• Global employment company (GEC) payroll. In prior sections, we discussed the setup and potential for using a global employment company to employ, pay, and administer benefits to employees who are continuously mobile. Companies who employ this model can pay employees offshore in a standard currency like US dollars. This model has been used in the past to pay those who frequently go on expatriate assignments, but we may see it come back as talent mobility grows.

How to Manage Compliance and Risk

Location Tracking and Compliance

When we founded Topia in 2010 and started speaking to HR leaders about their challenges from growing geographic movement, almost all of them told me that their biggest issue was tracking their employees—that is, knowing where their employees are and what they are doing at any given point in time. This is the “first order problem” of talent mobility—if companies can’t track employee locations and projects, all of the more complex strategic and operational tasks are irrelevant. Additionally, it’s impossible for companies to carry out their duty of care for their employees without clarity on where they are!

You might think this sounds crazy. I certainly did. But when you think about it further, it’s not. With growing talent mobility, employees are constantly on the move—across geographies, coffee shops, hotels, and homes—as well as working dynamically across project teams. And many of the workers at a company are not even full-time employees. Traditional HR systems were designed as a system of record with basic information for each employee: name, address, age, compensation, office, manager, department, entity, team, and so on. Since employees were in the office each day and had fixed roles, companies could easily look at their HR system and see where an employee was working. When expatriate assignments or relocations happened, the HR team updated the information in the HR system. But since these happened infrequently and generally lasted for a decent amount of time, this process didn’t cause too much friction. Travel systems were used to plan trips and process expenses but didn’t provide dynamic movement information, let alone link to the HR system to provide a single view of employee location.

In the talent mobility era, however, companies must track a complex employee footprint across geographies, locations, and teams. Without a global mobility management (GMM) technology system in place, tracking employee location is virtually impossible.

When we founded Topia, we made this one of the first focuses of our global mobility management system. We helped companies centralize their employee movement data in our system to provide a single place where HR teams could access all this data. This started with initiating each geographic mobility experience in the system, and then updating it as an employee footprint evolved. Through the years, we saw companies get many benefits from this centralization—from rapid responses to locating employees who may be at risk, to reviewing nationalities amid immigration law changes, to ensuring employees did not overstay their tax and immigration authorization (one of the biggest fears for companies in the talent mobility era).

“At the same time that working everywhere is getting more common, governments are getting tougher in protecting their borders,” says Nick Pond, Mobility Leader, EY People Advisory Services. “Company and employee demands don’t always marry up easily with the realities of government. People can’t just pick up and work where they want. Companies need to invest in the frameworks to make it happen within the constraints of today’s rules and regulations.”*

Tracking Tax and Immigration Compliance

When I was researching Topia, I heard many stories about employees who had violated tax and immigration authorization. Often this was from traveling across borders to work regularly without the right visa—like an employee who commuted between the United States and Canada without a work visa. Sometimes it was employees who overstayed a visa in a particular country, not realizing that it had expired—like an employee we heard of who was deported when a work visa expired. Other times, it was employees whose taxes were not calculated correctly by local payroll systems and then found themselves with big tax liabilities after returning home from an assignment. All of this stemmed from companies not being able to easily track where their employees were and how long they were in given states and countries and to ensure necessary tax and immigration compliance. Many companies hadn’t even implemented the basics of a global mobility management system, let alone the complex calculations and alerts for tax and immigration compliance.

Once companies implement a GMM system to track their employee footprints, they should ensure global tax and immigration logic is set up to flag risks as they arise—for example when immigration thresholds are hit (whether through travel, days in country, or renewal dates); when permanent establishment becomes an issue from working time in a given location where the company doesn’t have an entity; or what tax calculations need to be done based on the time working in a given state or country. GMM systems should come with this tax and immigration logic included and able to automatically prompt talent mobility teams, employees, and external service partners to take action when needed. Automating this in the GMM system streamlines the management of mobile talent and ensures employees can work everywhere while still meeting the compliance constraints of existing tax and immigration frameworks.

Responding to Geopolitical and Security Risks

With systems in place to track employee locations and ensure tax and immigration compliance, companies can then rapidly respond to geopolitical and security risks, an increasingly frequent consideration amid today’s uncertain world. If an event happens in a particular location, the company can quickly pull a real-time log of the employees in that location and use it to check their safety. If a law changes in a given country, companies can quickly categorize who may be affected and respond to it promptly.

In November 2015, a series of coordinated terrorist attacks took place in Paris, France. With a GMM system in place to track employee location, companies were able to quickly identify which employees were in Paris and start to contact them. Similarly, in January 2017, President Donald Trump issued an executive order restricting entry into the United States for citizens of certain predominantly Muslim countries. At the time of the executive order, many companies had employees of these nationalities either already in the United States, on their way to the United States, or with upcoming plans to come to the United States. Using the GMM system, companies were able to quickly identify who might be affected by this change of legislation and make alternative plans for them. We saw companies change the locations where they were hosting meetings, divert project teams to be based in other locations, and have certain team members long-distance commute to the United States rather than moving.

Eric Halverson, Head of Global Mobility at eBay, spoke about this experience at an industry conference in San Francisco shortly thereafter. “When the executive order happened, all of a sudden, we had to categorize our entire global workforce to know where people were, what nationality they held, and their visa status,” said Eric. “We had to leverage our systems and do it quickly. As the world becomes more globalized with geopolitical disruptions continuing to occur, I expect this rapid categorization and response will become an increasing need, and systems to power it will be critical.”

Managing Costs and Budgets

Scenario Planning to Fill Open Jobs

With constant talent mobility, companies also must manage dynamic scenario planning about how to move employees, budgeting for the cost of moves and managing the approval processes with business and finance owners. Traditionally—with infrequent movement—this process was handled as a one-off by global mobility (a part of HR), finance, and the managers involved. With near continuous movement, however, this manual process is inefficient and cumbersome. Therefore, companies automate talent mobility workforce planning, budgeting, and approvals in their global mobility management (GMM) systems, allowing for complex considerations of different scenarios for filling open jobs and real-time approvals for managing workers.

As we’ve discussed in prior chapters, the best practice is for companies to set up a talent marketplace listing open jobs and categorizing workers’ skills. When a job needs to be filled—remember, this happens continuously tied to dynamic projects—companies source potential candidates from inside the company (for development, skills match, or movement tied to disruption of a traditional job) and outside the company (full-time candidates and freelancers). As discussed in Chapter 5, the first screening of a candidate is for whether the worker has the skills needed for the job. Once a potential worker (or set of workers) has been identified with the skills required for the job, the company runs dynamic scenarios on how to staff them on the project team. For example, a company may compare hiring a new employee locally for the job, relocating an existing employee whose job has been disrupted by automation and investing in a learning program for the new job, expatriating a more senior employee who doesn’t require an investment in a learning pathway but is more expensive to relocate, hiring an employee in another location and supporting frequent travel or a long-distance commute to the new job, or hiring a freelancer who is completely remote. In summary, these scenarios should consider the worker type, location type, geographic movement, policy, and costs for the workers and job in a mix of configurations:

• Worker type. Scenario planning should look at hiring a new employee, existing employee, or freelancer to fill the job.

• Location type. Scenario planning should consider whether a worker needs to be physically at a job or whether he can work remotely and be hired from anywhere.

• Geographic movement. Scenario planning looks at the location requirements and then considers geographic movement configurations. If a worker needs to move to be physically at a job, scenarios should look at relocations and expatriate assignments. If a there is location flexibility, scenarios should look at short-term assignments, frequent travel, commuting, or fully remote work.

• Policy. Scenario planning should look at the policy for the different configurations above, taking into consideration the benefits provided and compensation, tax, cost of living, and retirement adjustments.

• Cost. Scenario planning should look at the costs of each of these configurations and compare them versus the contribution that the worker is likely to make to the company.

In the talent mobility era, there is a near infinite set of configurations for how a job can be filled by new employees, existing employees, and freelancers. To enable this, companies adopt a GMM system that can dynamically run a near infinite set of configurations and iterations, so that company leaders can make real-time decisions on how to fill jobs in the right way.

One of the most popular parts of Topia’s GMM system is Topia Plan, our cost projection and workforce planning application that allows companies to run parts of these scenarios. Traditionally, these projections were done in spreadsheets by the global mobility team or, in more recent years, outsourced to consultants at a Big Four accounting firm or relocation company, who charged high prices and then sent back a spreadsheet. Over the years, I heard countless stories from customers who were frustrated by this structure—if they needed to run another scenario or make a change, they waited days and paid another price for another spreadsheet. Or, if they needed to talk to a business leader tomorrow, the spreadsheet might not be ready. Companies adopted Topia Plan and saw dramatic improvements in their planning and approval efficiency. Many of them set up Topia Plan with the global mobility team running these scenarios on behalf of hiring managers; some of them took this a step further and trained recruiters, HR business partners, and managers across the business to run these scenarios—empowering them to easily plan how to fill their dynamic jobs internally or for clients (e.g., at consulting and engineering firms). This transformation dramatically increased efficiency across our customers and enabled business leaders to continuously consider how to fill dynamic jobs. In short, they could all embrace agile work.

Approving and Initiating Talent Mobility

After running scenarios and selecting a worker for a job, the GMM system supports an approval workflow with the business and finance leaders. Each of the designated approvers can easily review the configuration and cost of the selected worker, submit any questions, and seamlessly click on an approval button, replacing countless conversations and e-mails of the past. The GMM system keeps a log of questions and approvals for future reference, removing previous confusion that may have arisen without central documentation. The GMM system should send the approved cost to the finance system, where it can be accrued for in the appropriate management accounts, with the costs tracked going forward.

Once approved and logged in the finance system, the GMM system should automatically initiate a move, sending a notification to the worker, project owner, and any external service providers that may be required, such as immigration or tax firms. By initiating all geographic, location, and job mobility in the same system, companies create a single database of all mobile employees that they can use to dynamically track employee location, managing geopolitical and compliance risks (as discussed above). If there is a learning program tied to the worker’s move, it should be tied to her profile in the GMM system so that the development of competencies for the job can be tracked. We take a closer look in the next section at the full talent mobility systems roadmap.

Topia Plan’s approval and initiation workflow was another popular part of our offering. Our customers had been used to sending many e-mails to discuss selected workers and obtain approvals. This process was inefficient and cumbersome for them. With Topia Plan, this moved from days of back-and-forth to minutes of review and approval.

Systems to Enable Talent Mobility and Engage Workers

Core Talent Mobility Systems Map

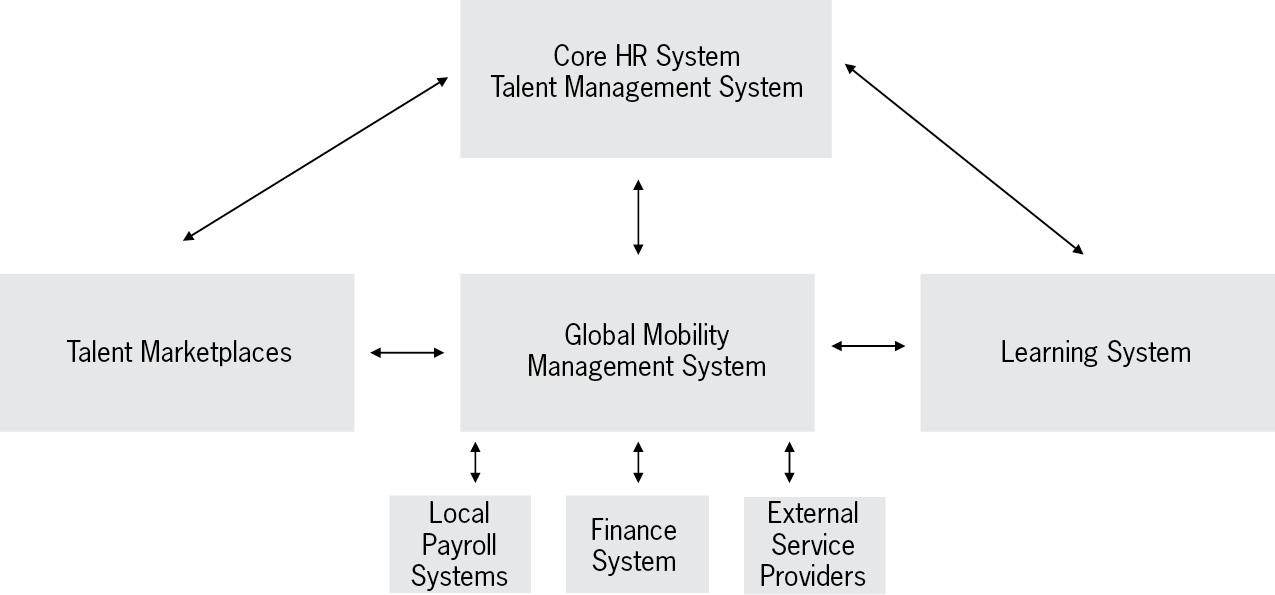

The GMM system is a critical part of enabling efficient talent mobility. But it is just one system in an overall talent mobility systems roadmap that makes talent mobility work. Implementing and adopting this systems roadmap is an essential part of transforming to be an F3 Company.

The talent mobility systems roadmap should include three core systems bidirectionally linked to one other and to a broader set of company technology platforms. This system structure should also connect to an ecosystem of offline service providers who carry out services like immigration, tax, relocation, and healthcare that support mobile employees. The three critical talent mobility systems are the talent marketplaces, global mobility management system, and learning system. Below we take a look at what they are, how they work with one another, and the other systems and service providers they should connect to:

• Talent marketplaces. As discussed in Section 2, companies should shift from fixed roles to dynamic jobs that include employees and freelancers. To enable this, companies should adopt a talent marketplace for employees and freelancers. The jobs graph should list all open jobs and the skills required for them. The skills graph should categorize employees, their skills, and competency levels. These should work seamlessly to recommend workers for jobs.

• Global mobility management (GMM) system. As discussed above, the GMM system is the backbone to make geographic, location, and job mobility work. It handles scenario planning to fill jobs, approvals for selected workers, initiations for moves, tracking and compliance for mobile employees, and a broad universe of logistics for geographic mobility, including initiations to external service providers, status updates on external services, and document storage. It should also handle compensation, payroll, and withholding adjustments when workers are working in different geographies.

• Learning system. In many cases, a worker is matched to a new job without all of the skills required for it. This may be particularly acute when a prior job is disrupted by artificial intelligence and a worker gets a new job that requires him to develop new skills or competencies. In these scenarios and others, employees may have a learning program associated with their new job and administered by a learning system. Companies should link their learning systems to their GMM system and talent marketplaces.

These three systems—the talent marketplace, global mobility management system, and learning system—are the backbone of supporting efficient talent mobility. You can also think of this as enabling continuous “matching, moving, and learning.” These three core systems should then be linked to the other company systems and service providers. Overall, the systems roadmap should look like this:

Employee Engagement and Collaboration Systems

The final piece to unleashing talent mobility is setting up the infrastructure for virtual work. With increasing geographic, job, and location movement, workers need robust collaboration and engagement systems to work seamlessly while outside the office. The key systems for workers in the talent mobility era are collaboration software, messaging applications, and virtual meeting technology.

• Collaboration software. With employees working virtually from places around the world, the need for digital collaboration increases. Gone are the days—like at Lehman Brothers—when files could only be accessed from the office and collaboration required printing documents and discussing them in person. In the talent mobility era, employees access files and collaborate from everywhere. To enable this, companies adopt collaboration software based in the cloud to support virtual work and access. Popular systems are: Box, Dropbox, Google Docs, or SharePoint. These should be adopted by all people in the company. Certain teams may also adopt niche collaboration software for their functions, such as NetSuite for finance or Confluence for product roadmaps.

• Messaging applications. With continuous movement and work everywhere, companies adopt messaging applications for worker communication. They shift from in-person conversations and e-mail to dynamic messaging applications, like Slack, that allow people to participate in multiperson conversations digitally and review what’s been discussed. This shift must start from the top with the company leaders adopting messaging applications and must become a part of the cultural and operational norms within the company, with expectations set in onboarding programs. Messaging applications should become the central hub where information, such as management reports, is shared and accessed even if it is produced in another system, like a business intelligence platform.

• Virtual meeting technology. With distributed teams and continuous movement, companies move from in-person to virtual meetings. Companies should adopt virtual meeting technology, like BlueJeans, and champion videoconferences as the standard for all meetings. Adopting a “videoconference-first” strategy ensures that all workers, regardless of location, feel included and equal. As virtual meeting technology evolves, companies may begin to adopt virtual reality meeting systems where workers don headsets and meet with others as avatars in a virtual setting.

Many technology companies use these systems as a part of their standard operations. Increasingly traditional companies are also making this transformation. When I worked at Lehman Brothers, we accessed files from the office, had meetings in person, and social media messaging was blocked—even LinkedIn. When I founded Topia, we immediately adopted Google Docs and Box for collaboration, Slack for messaging, and WebEx (later BlueJeans) for virtual meetings. When we acquired Teleport, Sten Tamkivi and the founding team had taken this a step further: they used collaboration systems for almost everything they did and set clear guidelines for using them.

“At Teleport, virtual and remote working was a core part of our founding principles,” says Tamkivi. “We set rules for which system to use when and for what. This is important so that everyone knows how to work, where to find things, and no one misses anything. This might sound mundane, but it actually makes people’s lives simpler. It doesn’t take away employee freedom per se, but rather starts to align them around default behaviors for using these systems that make it easier for everyone to work from everywhere.”

The Talent Mobility Revolution is the result of the seismic forces of globalization, automation, and demographic change. It has almost entirely changed the nature of work and the way that companies need to operate to be successful in the future. Much of what we have discussed in these three sections may seem difficult to enable and manage. But by implementing a core set of systems and championing adoption of them across the business, companies seamlessly harness the benefits of talent mobility—increased employee engagement, innovation, and growth. Peggy Smith, CEO of global trade body Worldwide ERC, puts it succinctly:

“In the next five years, companies are going to be very chaotic on the surface. For someone used to pretty org charts and fixed roles, the new project-based way of working will seem very complex,” says Smith. “But under the hood, companies will be incredibly efficient. They’ll be agile to respond to disruptions and opportunities. They’ll apply the concept of mobile talent to see results for business and customers’ wants much more quickly. They’ll tap into vast networks of workers to mobilize and bring people together to complete projects. And these workers will develop their own vast networks because they will work with many different people for short bursts of time.”

Transforming systems and operations is the ninth and final step to success amid the Talent Mobility Revolution. To succeed, companies must restructure their business and talent operations across employment strategy, workforce planning, and payroll. They must implement a new set of systems to power their F3 Company, following the talent mobility systems roadmap. Companies that effectively make this operational change will be set up to harness the benefits of talent mobility for their businesses and workers.

In these three sections, we looked at the nine steps of talent mobility transformation. Any company that follows this playbook will be ready for success in the Talent Mobility Revolution. We conclude the book with a final chapter on how to unleash the Flat, Fluid, and Fast economy everywhere, looking at how to transform traditional companies, start new companies, and reinvent government policies.

_____________________________

* Interview with Nick Pond, Partner, EY People Advisory, December 17, 2018.