CHAPTER 6

LEARN ALL YOU CAN FROM EVERYONE YOU CAN

If you want to go fast, go alone; but if you want to go far, go together.

—AFRICAN PROVERB

None of us can transform by ourselves. And as the product manager of your personal transformation, an essential component of the Design step is to map who your key stakeholders are. In this chapter, we explore how having the right tribe has the potential to propel your goals even further. Throughout this chapter, I describe how to create a stakeholder map, and I will guide you through the process of designing to have the right people in your life. You will also learn how to identify, assess, and prioritize your stakeholders and plan for how you will engage with them, adding all this into your plan of action.

When I was younger, I didn’t know the value of role models, mentors, coaches, accountability buddies, and sponsors. I didn’t know there was a thing called “networking,” and I certainly didn’t think there were folks who would want to help me win, so I didn’t go after them. But the millennial professionals today are some of the most connected and stakeholder-oriented people I have seen. However, even these well-connected millennials will still need to ensure they are connecting with the right people. There will be people who may not be interested in you but will still influence the outcomes of your project, your career, and even your compensation. Still, you are the product manager of your personal transformation, and as we know, products have:

• A market of customers—those who buy/rent and consume what the product offers

• Supporters

• Detractors

• Competitors

As a product going into the market as a new and improved version, you will encounter people who want what you have to offer, who may not want what you have to offer, and those who don’t care. And they will all have varying degrees of power and influence over how successful your product will be in the market. Let’s see how having a map of stakeholders is critical to your being able to win when they say you won’t.

STAKEHOLDERS ARE CRUCIAL TO YOUR SUCCESS

Who are the people who have an interest in your growth and development, and/or may be able to influence your success? It could be your boss, your bank, your fellow employees, your mentor, your former college professor, or your spiritual advisor, for example. Stakeholders include anyone who will speak on your behalf; will pour wisdom, guidance, and support into your life’s bucket; has an interest in or is impacted by you as product, or your plan; and/or can influence your journey in any way. Determining as much as possible who these people are and how they feel about you and your project will help you decide how much and what kind of attention you should pay to each of them in order to keep your plan on track. This is sometimes a difficult thing to embrace—that you cannot “go it alone” or that you are not “self-made” and don’t need anyone. Yet as we listen to winners we know—most people who win talk about those who helped them along the way.

My sixth-grade teacher, Mrs. Long, introduced me to the “time out” if I played during class or caused other mischief. I learned about consequences of my decisions from her. Mrs. Buckner (the mother of former NBA star Quinn Buckner) was a teacher at my grade school and taught me the importance of understanding history, which I value to this day. Those two teachers were just the first of many people who helped me win, in some way.

There are internal stakeholders, such as a spouse, a partner, a child, work colleagues on your team, a close family member, or a best buddy, who will be affected if you take a larger new job or move to a new city. If the context is strictly your job, then your team, your boss, your peers, your mentor, your sponsor, your CEO, and perhaps the board of directors would be internal stakeholders.

You will also have external stakeholders who may be less affected and may impact your life objective or project less than the internal stakeholders, but they could still be important. You may not know them well but may still need to get their support. These could include suppliers, end users, customers, the community, and professional organizations that are a little further away from your initiative than the internal ones. Their low influence could easily change into high influence—for example, with an acquisition, a new role, or someone whispering in their ear—so their status as an influencer may be fluid.

Here’s an example of how I really got the point of the value of stakeholders and how they can affect not only a project but an entire career. When I was making my high-power move across the J&J enterprise (albeit slower than I wanted), I was on my way to J&J’s Medical Device & Diagnostic Division, and Connie S. was the president of OCD—Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, one of the companies in MD&D. During my onboarding orientation, Connie told me she was leaving. “Leaving to go to which other J&J company?” I asked. I was disappointed that she was leaving OCD, but I assumed she was going to be around J&J, which I was glad about. I’d never worked for a female president, and I had accepted the move to this company because I wanted to work for a female president.

She told me she was leaving J&J. “Why?” I asked. She then sat me down and told me about the facts of sponsorship. She hadn’t met her revenue quota for a second consecutive year, and she didn’t have anyone who would spend influential capital on her to help her get a third chance to hit her targets in the upcoming year. In other words, she didn’t have a stakeholder who could be her sponsor and support her.

Sometimes it is an effective strategy to rely only on yourself to drive your own performance. But I believe we should not move alone or in isolation. We can be leading the pack, or we can be part of the pack, but we can’t go everywhere alone. It’s far better to have other people in your back pocket or on hand to come in on your behalf in case you eventually encounter a tough situation, like Connie encountered. You may at some point need someone to speak on your behalf. Connie didn’t have that network of support, so her warning for me—especially as a relative newcomer to J&J—was that I needed to establish my network of contacts and stakeholders early and “keep them warm” so they would always be ready to go to bat for me.

That made me think, “Who were the people in my corner?” After this experience with Connie, I thought about my stakeholders, and as I identified them in my mind—both inside and outside J&J—I realized that some stakeholders I was thinking about would have an interest in me and others would care less. Not all stakeholders who were in my circle would be in my corner.

Also, some stakeholders will have high influence in certain circles about my career, and others will have low influence. I had to make sure I knew who had high influence over my career and what was important to them. For me, those stakeholders were IT people, executives in the J&J ivory tower, and the business leaders I worked closely with. On the outskirts were any non-J&J people who may have been there for me, like my IBM branch manager, Tony Waiken or my desk mates and friends, Maggy and Pat, in Houston. I needed to understand who my stakeholders were and why they were influential. Then I had to ensure they would have a positive influence on my career. The best way for me to do that was to ensure that where appropriate, I had a positive influence on their objectives!

RECOGNIZE THE IMPORTANCE OF PERFORMANCE, IMAGE, AND EXPOSURE

Around the same time that Connie told me about the value of stakeholders, I also learned about performance, image, and exposure (PIE). Sadly, as an African American young woman, some of the most basic things in business were not shared with me. Many of us who grew up in Black families were not afforded to have executive mothers or fathers who understood what it really takes to win in corporate America. Mom and Dad were more about us being obedient and following guidelines than understanding relationships, politics, or brands. Although many people in the majority may have not had exposure to executive parents, I came to find out that they were given mentors and sponsors to help close the gap faster and more readily than what came to people like me.

At J&J, I was cochair of the African American Leadership Council (AALC)—a Black affinity group that focused on driving more insights, information, and promotions into leadership within the Black professional community at J&J; AALC also helped those majority (white) leaders work closely with us to enable executive sponsorship for Blacks into positions of increasingly higher leadership. One of those things we learned was “It’s not only about performance [to our collective surprise], but also about exposure and image.”

As we talked about it, it became clear that that’s why deals are made on the golf course: those folks playing golf together have a relationship, and exposure to one another, that goes beyond nine to five. They sit together at lunch, or their kids go to the same school: they have things in common. The Black employees were pretty much left out of that—until we realized we needed to focus on more than performance and had to forge a way to understand, improve, or maintain our image, and to establish more meaningful relationships to drive greater exposure.

When you are at a higher level in your career and in your community, excellent performance is assumed. Your performance must have been great all along, or you wouldn’t have gotten to a senior-level position. You are likely on par with or maybe a little better than someone at the same level, so it is mostly your brand/image and your exposure to influential leaders that will actually be what differentiates you from others (in other words, that’s your competitive advantage, or for many people of color or women, that is our cultural advantage/culture add). It is the combination of your brand (image) and the people who know you and will speak for you (exposure) that will likely determine if or how quickly you go to the next level.

In his book Empowering Yourself: The Organizational Game Revealed, Harvey Coleman describes his concept of PIE. I highly recommend his book. Here’s my brief synopsis of PIE:

• Performance ideally means you do your job very well. You and your boss likely discussed and agreed on performance criteria. Where possible, you deliver earlier than expected, at lower costs than budgeted, and with greater impacts than planned. You don’t only meet objectives; you exceed them. You understand the business drivers and are a value-added contributor.

• Image is your brand. How do people describe you—in terms of how curious or innovative you are, how you dress, how well you work with others? Are you a servant leader? Do you have empathy for others, and are you a silo buster? Are you always late? Are you confrontational? Do you have integrity? When people find out you will be attending a meeting with them, are they glad, concerned, or indifferent? As a product, your brand is in your “market.” And markets will always have a point of view of a product or service they consume or encounter. TV shows get renewed or canceled each year, products get taken off the shelf or placed higher/lower on the shelf, products get repackaged or redesigned, or have a new recipe as a new version of themselves. Products that are very popular may have their price rise because the market values them more than others. So it is the same with our image and our brand. Our image needs to remain high.

• Exposure is about whom you know and who knows you. Exposure is the most important element of driving your career forward. You can’t get promoted without your boss agreeing. You won’t get mentors without them knowing who you are. Who will speak on your behalf when you are not in the room, or not on Zoom, with the others? Performance is table stakes, but exposure is the lifeline that keeps you floating and rising. Exposure can be a two-edged sword: beware! Usually women and minorities tend to be underexposed; and if you are underexposed, you risk not being known or recommended for an opportunity, because folks have simply never heard of you. On the other hand, if every time someone participates in an extracurricular event or looks at an internal magazine and continually sees you or your name or picture, you risk being overexposed. You may be doing your job very well, but at some point someone will wonder if you are selling yourself too much and not doing your job enough. Exposure is key, but it’s the right level of exposure that works.

My former colleague and still friend Connie may have known the principles of PIE, but she sure didn’t seem to apply them. I can only imagine that as one of the very few female CEOs at J&J, and the only one in MD&D, she may have felt alone, didn’t feel exposure mattered, or maybe was uncertain about how to drive relationships with the men.

There are cases where women help other women—I was also a member of WLI (Women’s Leadership Initiative), led by Joanne Gordon. Joanne was a great financial leader and became the CIO of J&J while I was there. Similar to the AALC, WLI helped improve women’s leadership and awareness to enable them to get into and stay in leadership positions. Why didn’t Connie benefit? I don’t recall Connie coming to many of the WLI events, which may be the reason she didn’t reap much. She didn’t sow much into the value of WLI.

Identify Possible Stakeholders

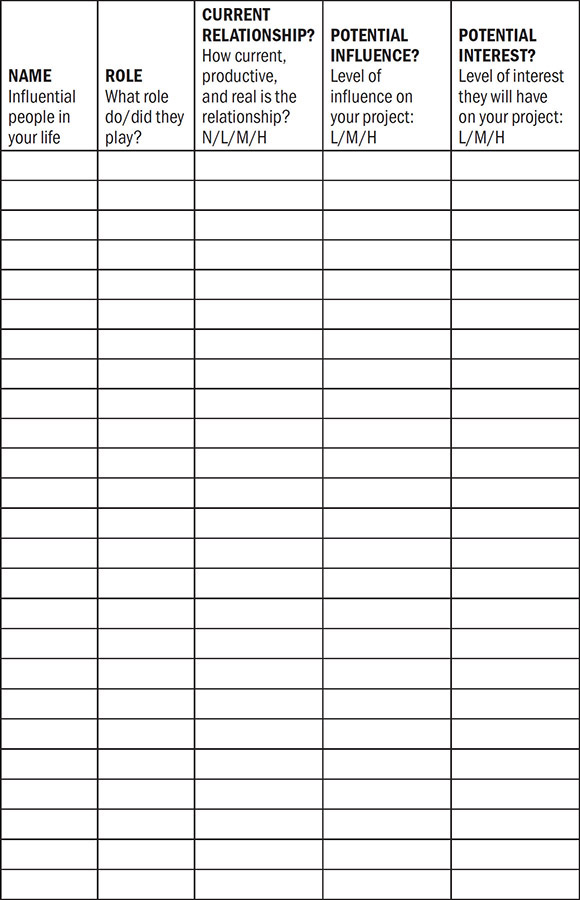

Table 6.1 is a stakeholder list spreadsheet to help you identify your stakeholders.

TABLE 6.1 Current Relationships

The first thing you should do is list every key or influential person by name (in Column 1) and add what role(s) they do or did play in your business or personal life (in Column 2). These influencers can be customers, your boss, and/or your top team leader who served as your go-to in times of challenge or who might have become your successor. It is anyone you assert is key and influential in your life.

In Column 3, assign whether or not you have a real and current relationship: you can assign none (N), low (L), medium (M), or high (H). For example, you might put “none” if that person is a role model you haven’t met—yet. Or a neighbor you don’t know at all, but you may know about the neighbor and could use her help.

In Column 4, assign the likely “influence” that person may have on your Plan of Action—again, low (L), medium (M), or high (H). Will the person have a high level of influence over resources, money, or the outcomes of your objective? For example, if your boss’s name is in Column 1, then I would suspect he would be a high. Your CEO’s influence may be high or low, depending on your level in the organization.

In Column 5, assign the level of likely “interest” each person may have in your Plan of Action, again using low, medium, and high. Will the person be highly interested in what you are looking to do? Or just moderately? As you fill in Column 5, keep these questions in mind:

• If you indicated someone will be interested, why will that person be interested in your objectives and key results?

• Will that person be positively or negatively impacted?

• How would you like that person to contribute to the project? (What do you think you may need from that person?) It will be difficult to get a stakeholder to support your objectives if he or she will be highly negatively impacted by the project. But that person still may be interested. You need to know if each person will be interested or not—because that will affect your plan of action. For example:

![]() Do you need money/capital to start your own business?

Do you need money/capital to start your own business?

![]() Do you need that person to coach you?

Do you need that person to coach you?

![]() Do you need that person to support you by picking up your child after school for six months while you complete your degree?

Do you need that person to support you by picking up your child after school for six months while you complete your degree?

• If you don’t have a current and real relationship with the stakeholder, do you need to build one?

Do this stakeholder exercise now. Free form is fine—just make sure you can read your writing!

Bear in mind that the purpose of identifying the individual stakeholders is so you know who they are and can pay attention to them at the right moment so their impact is minimized or maximized depending on their negative or positive influence on your objective. First, you will see if any of them are in your corner (promoters), are not in your corner (detractors), or don’t have a point of view (neutral). You will eventually map them into one of the four boxes in Table 6.1, and you will see what category they fall in. Don’t do the mapping now. You will do that later in the chapter.

UNDERSTAND THE POWER OF SPONSORS, MENTORS, COACHES, AND ROLE MODELS

As you read about the need for performance and image, remember that the third word in PIE—“exposure”—is important because it is through your exposure to your stakeholders that you win. Stakeholders can be anyone who will invest time, money, wisdom, faith, experience, influence, connections, and other factors to help you win. Let me briefly review the different types of stakeholders, including one type that may not even know he or she is your stakeholder.

Sponsors

Sponsors are people such as CEOs, other C-suite leaders, and high-level community, political, or religious leaders who may (should) know you. They vouch for your character and your performance as you are progressing through your professional career or through different aspirations that you have in your personal life, your community, and educational settings. These sponsors have a high degree of influential capital. Their influence is likely reserved for the most promising of leaders, and they usually reserve their capital for leaders at a higher level whose performance and brand they get to observe. You can trust them to speak on your behalf and suggest your name when you aren’t in the room or on Zoom.

When I wanted to join a board, I needed to reach out to my former SVP peer (who was a white male chief human resource officer) to speak on my behalf as a reference. He had high influence on my soon-to-be chairman—they had gone to Harvard together—and he was ready to support my joining a board. He spoke on my behalf to the board chairman.

Even after I achieved the objective of getting on the board, I continue to connect with him on LinkedIn. I call him occasionally to check in, and I send him quick messages congratulating him on his latest achievements. I want him to know that our connection extends beyond what could benefit me at a specific time and I am grateful he served as my sponsor to join a board.

Mentors

Mentors can also be C-suite leaders, board members, other colleagues, community leaders, revered elders in your community, and other stakeholders in your life who will be available to you for regular feedback on a monthly or quarterly basis. You will have fairly easy and regular access to them via periodic in-person meetings or phone or video communication.

When I was in Texas around 1987, ten years after joining IBM, I had a branch manager who was intent on helping me succeed. His name was Tony Waiken (I briefly mentioned him earlier in the chapter). He was a highly successful and older white man who took an interest in my career and wanted to help me win. He saw when I worked well, and he saw my mistakes, but he also saw my love for our customers and my desire to solve problems to uphold IBM’s values. He gave me feedback to help me serve our customers even better. When he promoted me, he gave me some advice, the kind of advice a mentor would give you, and I viewed him not only as my mentor, but as a sponsor as well. After all, he spoke on my behalf to his constituents, and he promoted me to a position in Dallas where I had responsibility for teaching new systems engineers how to manage large systems. In the way he spoke to me and the advice he gave to me, he seemed like my dad sending me off to college. He gave me great life management advice, including this:

1. Know whose career is primary between you and your husband (or partner). Whoever has the primary job may have a larger say in when or where you could relocate for a new job. (I never would have thought of that on my own.) He was talking about the Five Fs, and I didn’t know it. The family may be impacted by a relocation that comes as a result of furthering your career. In your POA, you would have put your family as an area to focus on to ensure your POA is “risk adjusted.” This is a consideration he was giving me. “Who’s going to decide whether your family should move? Daphne, right now, it’s you.”

2. Understand how many nos you’re worth. There are only so many times you can reject a company’s job offers. Tony told me I would be offered many jobs and relocations and I would find something wrong with each one; they wouldn’t all be perfect. But he advised me that I could not say no indefinitely—at some point, companies would stop offering. This made perfect sense—it was like me trying to find the perfect spouse who had perfect hair, clothes, finances, fitness, faith, and a private jet lifestyle. At some point, I needed to know what part within an offer was a dealbreaker for me, and what was not, and just say yes.

3. Be aware of the differences among role models, mentors, coaches, and sponsors: they are not the same, so be clear on when you need which one. If you don’t know, then ask one of your stakeholders who has career experience in whatever objectives and key results you’re going after and who will look out for your best interests. Identify who is in your life as a role model, a mentor, a coach, or a sponsor. Engage people before you need them, and certainly engage them when you do need them; don’t go it alone.

4. If you want to win, watch and see which people have the power and winning actions in your organization or team. (In the EDIT vernacular, these are role models.) Watch and learn how, why, and when they move. See the patterns and learn from them. Then you will be able to predict how they will move—and then use applied learning to then move better than they might have when you find yourself in a situation that is similar.

5. Be ready to play the game, and score points. Either you will watch—and earn no points on the board—or you will play and get the chance to put points on the board. Know when to move, and when to watch, and know which moves will or will not score you points. (Scoring points is when you achieve a win—could be successfully completing a tough project, landing a big client, beating a competitor, integrating your ERP, launching a new business services function offshore, or leading the pack with revenue, share, margin, customer satisfaction, etc.)

Mentors will shine a light for you on the virtual ground so you know where to step, where the potholes are, and what the culture of the organization or team is, and more. What time does the 8 a.m. meeting really start? Probably at 7:45 a.m., your mentor will inform you. In contrast, a sponsor shines a light on you in a differentiating way so other influential leaders can see you more than they see your peers. The sponsor will use his or her positional capital to go on the record advocating for you, the protégé.

A mentoring or sponsor relationship could last a lifetime. The mentor or sponsor could be inside the company or may be a professional with a similar background who is outside the company. Your mentor or sponsor could also be a person within any profession who understands how to handle the challenges you may be facing.

As a high-potential performer at J&J and the head of the African-American Women’s Leadership Council’s Affinity Group, I could, with other members of the council, connect with the highest-ranking leaders of J&J. (Note: This group was similar to the AALC I mentioned earlier, but the members were all Black women. We decided that the AAWLC was redundant to the AALC [which had men and women] and combined it with the AALC. We chaired the new combined group with one female cochair [me] and a male cochair [Zack]). Even in 2004, we discussed and sought to influence such issues as Black lives matter; and the high percentage of Black turnover in lower management. We were asked to help change the number of Blacks that made it into senior management and we set targets against a baseline. In support of driving more Blacks into senior management, J&J asked me to help the company create a mentoring program where high-potential senior African Americans would be assigned to high-ranking white leaders who would serve as mentors and sponsors. The relationship was more formal and would sometimes include reverse mentoring, which allowed Black protégés to give back and coach the white mentor or sponsor on business, cultural, or technology topics.

Coaches

Coaches are the people in your life who will be in the trenches with you to help you improve your professional performance at work. For example, you could be assigned to a voice coach to help you with your vocal delivery and presentation style. Another example—we had acting coaches from Second City (where many Saturday Night Live actors come from) who would help us know how to “act and look comfortable” on stage when doing a presentation, and how to ad lib when thrown a tough question from the audience we are presenting to. You could also work with a life coach in your personal life to help you develop confidence, or hone conflict management skills, or improve your parenting skills. Coaches will give you one-on-one support to help you improve in areas where you are weak or help you refine your strengths.

You should not mistake the need for training with coaching or mentoring. If you have never managed a team before, you need to go to a management development class. Your mentor or coach will not teach you all you need to know about managing a team. Your coach will help guide or offer advice on the foundation you already have as someone who has gone through management development.

Role Models

Role models are those aspirational “targets” of your attention, whom you look up to and may not ever meet. They may not be influenced by your project, and they may not care. They may have little direct impact on your project, but they may indirectly impact it because you may be encouraged and inspired by their ability to win, their approach to challenges, their level of capability, or any number of other things. As you think about them, you wonder how they might handle your situation, and as a result how you think may reflect a higher or more tactical or more holistic way of thinking, and you may begin to channel them in some ways. Some of my role models include Oprah Winfrey (entrepreneur, ability to scale, give the people what they want), Elon Musk (intellect, risk taking, innovation) and Harriet Tubman (courage and reaching back to pull others forward). I respect the leadership and innovative qualities that I believe each of them brings (or brought) to the table, and I aspire to incorporate their best leadership qualities into my own life.

FIND THE “RIGHT” MENTORS WHO GIVE AUTHENTIC FEEDBACK

I’ve been asked if mentors should be the same race as the protégé—in my case, as a Black woman, should I have a Black mentor or a mentor of color? Most of my mentors have been either white men and women or Black women. I’ve been fortunate to also have a few Black men as mentors, but the availability of Black men was lower in my various corporations. Either their levels were not as high as mine (which doesn’t mean they could not have been my mentor on a particular issue), or those who were organizationally higher than I seemed either less “available” or less secure. In white corporate America, I’ve seen Black men be hired to impressive roles, only to find that they just couldn’t assimilate or fit in with the culture. Their fault or the company’s fault? Each case was different—far too often, they were the ones who were called on the carpet when things got challenging (not the company). Often, Black men are waging their own battles of being the “only” or the “first” Black in their senior leader role, and they were doing what was needed to jump the glass cliff or stay focused on winning at their level. So I found more Black women and white leaders to support me.

I do believe, however, that cross-gender and cross-race mentoring taught me nuances about how to move up in organizations, given that as we go up, we will tend to be surrounded by mostly white men anyway. I’ve had mentors I selected and some who selected me. I’ve participated in formal mentoring programs (i.e., J&J) and natural selection mentoring. It can work in multiple ways, but at the end of the day, you want to be a good protégé.

And in regard to mentoring, this is a question I get asked a lot: “How do you ask someone to be your mentor?”

Personally, I found people who I believed were good or great role models, who had values that aligned with mine, and who were in positions at a level that was close to or at the level of responsibility I felt I could eventually achieve. All my mentors were highly regarded and respected leaders, and all were successful.

As a member of WLI and the AALC (and the former AAWLC), I was able to be in the company of senior business leaders. For example, WLI included presidents, senior female officers, and VPs. One of the women at WLI, Karen, was the company group chairman of another part of J&J. She and I connected and worked together on a WLI survey aimed at all J&J women directors and above, to understand their challenges with rising to the next level. She invited me into her office, or we met for lunch.

As we worked on aspects of WLI, I also gave her an idea about how to drive not only gender diversity but also race diversity into leadership ranks. She was intrigued. I shared with her my ideas, and she liked them. At the same time, she asked me how things were going and what my career goals were. Without complaining or disparaging—it’s important to never bad-mouth anyone, because you never know whom the people you’re speaking to know or in what high places their friends are—I spoke of how I wanted to do something significant for OCD. She told me to find a problem that OCD had, a problem that was big, impossible, valuable, and visible. If I could solve that, my name would be virtually “carved in stone” (not a headstone!).

I took her advice and asked her if I could meet with her again on this specific topic of my career, and she was very open to that. I met with Karen continually, not only about my career, but about other issues as well, because I had free access to her. I found the project I wanted to do; I just had to gather up the courage to do it. To this day, I would still call Karen a mentor.

This isn’t how every mentoring situation starts, but if you can find something of interest to both parties (you and your mentor) to serve as an icebreaker, then you can drive a relationship with the benefits of mentorship.

It also works if you share with someone you’ve seen at a distance something complimentary—perhaps that you admired the speech the person gave, or that you liked an article you read about the person, or that you thought the business results in Q2, for which the person was responsible, were outstanding. Let the person know you would love to pick his or her brain on a certain topic: that is flattering to the leader, and most leaders want to give back to employees or the community, even if they may not already be doing it.

You set up a meeting with them, and then you can spend time listening to their story and their approach to whatever the subject was. Then you seek to get some small advice on the opportunity you are facing. Start small—don’t unload everything at the first meeting. Afterward, make sure you reflect on these three questions:

1. “Did I appreciate their time, and did I send them a quick email (not too long) thanking them and specifying what my takeaways were?”

2. “Was I open to trying their suggestions?”

3. “Am I willing to follow up with them in two to four months?”

The answer to all three questions should be yes!

After repeating that cycle and meeting them again (and again) to give them a recap on how their advice helped you, as I did with Karen, they will become a de facto mentor.

Some companies have formal, arranged mentoring opportunities. Talk to HR and find out if your company has that. Sometimes it is for those deemed as high potential. If you are high potential, you will get the tap on the shoulder. I have been asked to coach a high-potential leader in one of my board companies to help prepare her for public board service. The coaching/mentoring opportunity is coming to her.

Other people can simply ask someone to be their mentor, but I’ve found more times than I can count that the leader in question believes he or she is too busy to be a mentor for yet another person. The way I suggested earlier achieves the same thing, without the formal label of “mentor.” Over time, it will be a label you can use for that relationship, but not in the beginning.

However, no matter how you find your mentor or how your mentor finds you, it’s very important that whenever your mentor suggests you do something, do it. No one wants to advise someone who will not listen and not follow through. That is an easy way to never get on the mentor’s calendar again. Even if you had to alter the mentor’s suggestion to fit your situation, that’s OK. Mentors want to know you are a good protégé.

My dear friend Monica Bertran (a digital leader and former TV broadcaster at Bloomberg) and I were sharing stories about protégés who don’t listen. Monica was working for Bloomberg in London when a woman came from Spain to work on the London project management team. This woman was smart, proactive, and eager to learn, and she did well while in London, but then her boss left, and a new boss came in. (As I mentioned earlier in the book, sometimes the person who hired you leaves, and then you have a new boss who “inherited” you, and the new relationship doesn’t always work.)

This woman was not ready for the shift and didn’t adapt well, because of many factors: the Covid-19 lockdown, her isolation from her family back in Spain, her new boss doling out some of her responsibilities to others, their poor relationship, her getting Covid-19, and more. As a result of all this, she was miserable. The nature of her work was changing, and she didn’t know what to do.

Monica stepped in to coach her and talked through a plan with these steps:

1. Write down her satisfiers/dissatisfiers.

2. Define the dream job so they could see the gaps.

3. Discuss which of her skills were transferable into other roles.

4. Identify who might be willing to sponsor her.

5. Speak to her manager about goals and ask for help.

Monica encouraged her to do some self-reflection and praying, plus she needed to focus on herself more, and not on the negative aspects of her manager.

Monica’s protégé seemed eager to move with this plan, but when Monica didn’t hear back from her for four months, she figured something was going on. It turned out that she didn’t use the tools or the approach they had discussed, and she was now contemplating running away. But she didn’t have a plan she was executing or a job to go to.

Remember, we shouldn’t run from something, but rather run to something. This woman was about to do the wrong thing. She was still focused on her negative relationship with her boss and not focused on how she could learn from her situation or highlight and showcase her great skills.

The end result? Monica did not see a way forward with a protégé who wouldn’t listen to her advice and try to help herself. She is no longer her mentor.

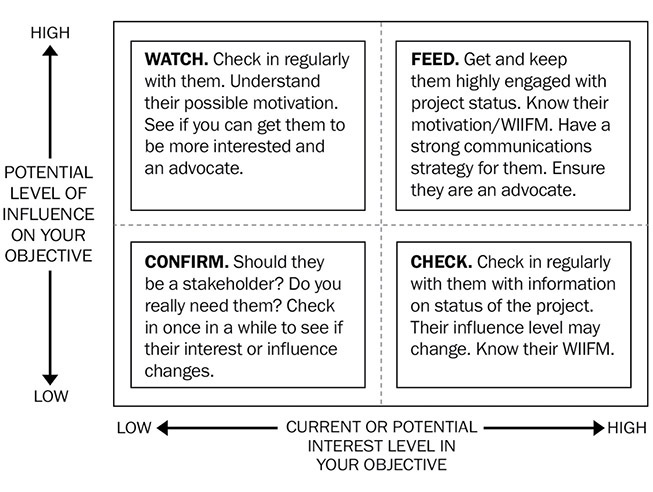

BUILD YOUR STAKEHOLDER MAP

Now that you know the difference between sponsors, mentors, coaches, and role models—and how each type might help you win when others say you won’t—let’s take another look at the stakeholder assessment introduced in Table 6.1. Let’s identify what you will need to do with the various levels of influence or impact your stakeholders have, by building your stakeholder map—see Figure 6.1. Remember you identified in the stakeholder assessment spreadsheet to what degree you believe your stakeholders have influence on your project (L/M/H) and the degree to which they are interested in your project (L/M/H).

FIGURE 6.1 Your stakeholder map

You will be placing your key influencer’s name in the appropriate quadrant based on what you believe the person’s level of influence and level of interest will have be. You will use your work in Columns 3 and 4 in the stakeholder assessment to determine where to put the stakeholder on the chart.

Figure 6.1 shows which category people will fall in to help you know how and when to get them engaged: watch them, confirm them, check in with them, or feed them.

Instructions for Filling Out the Map

Add your key influencers on your map by placing their initials in one quadrant on the chart based on their level of influence and the level of interest you believe they will have.

1. Low interest, high influence. Watch them and provide pertinent info to them at key project milestones. Understand where they may be able to influence, and understand their WIIFM (what’s in it for me) to see if their interest may grow. You don’t want to be caught off guard if they are able to influence the project but don’t really care about it

2. Low interest, low influence. Confirm. Here, not much activity is required. Monitor on occasion to see if the status changes. Confirm if they are even stakeholders.

3. High interest, low influence. Check in on them on occasion. Their influence may change. Monitor their status.

4. High interest, high influence. Feed. Manage these stakeholders very closely, understand what motivates them, and keep them highly engaged and informed with regular meetings.

Do you see a pattern? Are most of your stakeholders highly influential but not likely to be interested? Or the other way around? This is another way of positioning your stakeholders into a category for prioritizing your actions.

If you have stakeholders that have low influence but are highly interested, that could be helpful, but you should look to find those stakeholders that can be highly influential and interested. Then you will have greater momentum. Using those four categories, you will interact with them based on the interest and influence of each.

Engage with Your Targeted Stakeholders

Now that you know the interest and influence levels of all your possible stakeholders, and you know how supportive each may be of you, it’s time to plan your engagement strategy. You need to confirm:

• What you need from them.

• How they may benefit or be affected by your project (WIIFM).

• When it is best to engage with them.

• What your communications will be to them—and the more important they are to your project, the more important your communications are!

You will engage at the right time with the stakeholders based on where you are in your action plan and what your stakeholder needs are. If you have any stakeholders who are high influence/high interest and are clearly detractors (i.e., not in your corner), your strategy for dealing with them will be different than if a stakeholder is an influential promoter.

No matter their status, monitor them to ensure you are aware if their status as an influencer changes.

During my time at Johnson & Johnson, I was disappointed that I had not received a promotion from director to VP in seven years, although it was under that premise that I had joined J&J in 1997. While serving as executive director at one of the J&J companies (OCD), I was part of a conversation where I was told that the company was technically unable to see its profitability in realtime. They had to wait until February each year to see how profitable the prior year was. I thought to myself, this makes no sense. How will the company know which products are selling with the highest margin? Which customers should we raise the price on versus service better? How does the company know if it is offering the right volume discounts to the right customers who are ordering at the right level? I know the company has the data available. I then remembered the conversation with Karen, my mentor, and I said to myself, “Is this the big, visible, valuable, and impossible project she talked about? . . . Yes!”

I immediately volunteered for the opportunity to help the company remedy its low visibility of key data and to help the leaders see their global numbers. Everyone told me this was impossible because the holdup was with the international division of the company: the stakeholders in Europe didn’t want to share their data with “big brother” (i.e., the US team). And if we approached the project trying to get a global data project going the traditional way (i.e., starting with the United States first), we would lose the EU team. Clearly, our European colleagues were important stakeholders for our project. “Impossible? Did you say impossible?” was my question. Hmm. I’ve heard “impossible” before, and I’ve learned that what is impossible yesterday is merely inevitable today. “Challenge accepted,” I said.

I told my boss, “If the problem is in international, I’ll start with Europe and then get the data needed from the United States afterward. That way, the folks in Europe won’t feel like second-class citizens or like they’re at the back of the line.” I contacted our European partners and assured them that we were going to find a way to help them track their profitability and then expand our process to the United States, Asia, and Latin America. I gave them the WIIFM. I worked with a team that analyzed their tools, data, and processes. We gained their trust, and we were able to create an app that allowed the relevant sales data to flow from their system into the app with calculations of profit, volume, and other key indicators. After that, they were able to look at a variety of scenarios, chart customers, and create graphs. The entire outcome was positive, and we helped our international colleagues enhance their profitability and performance.

People around me had said it couldn’t be done. They told me I couldn’t win. I had to do the extraordinary. Two months after I showed my solution to the company group chairman and the CEO, I was promoted to VP IT. Working with key stakeholders (the VP of sales ops, the VP of sales, the IT department, and others), looking at the challenges from another vantage point (a non-US vantage point), and embracing the wisdom and knowledge of the team were all critical to my success. I never forgot that, and I ensured I was always aware of the power of stakeholders.

My experience is often known as the “glass cliff”—a phenomenon where someone (especially a woman or a minority) is offered a chance to get a leadership position, but it is offered where the stakes are high, it’s very visible, and there’s a high chance of failure. So you can jump off the cliff, and if things are not done just right, your parachute may not open and you’ll have a crash landing—often fatal for your career! In this case, however, my plan worked for me; my company rotated out the sitting CIO, and I was promoted to CIO/VP IT.

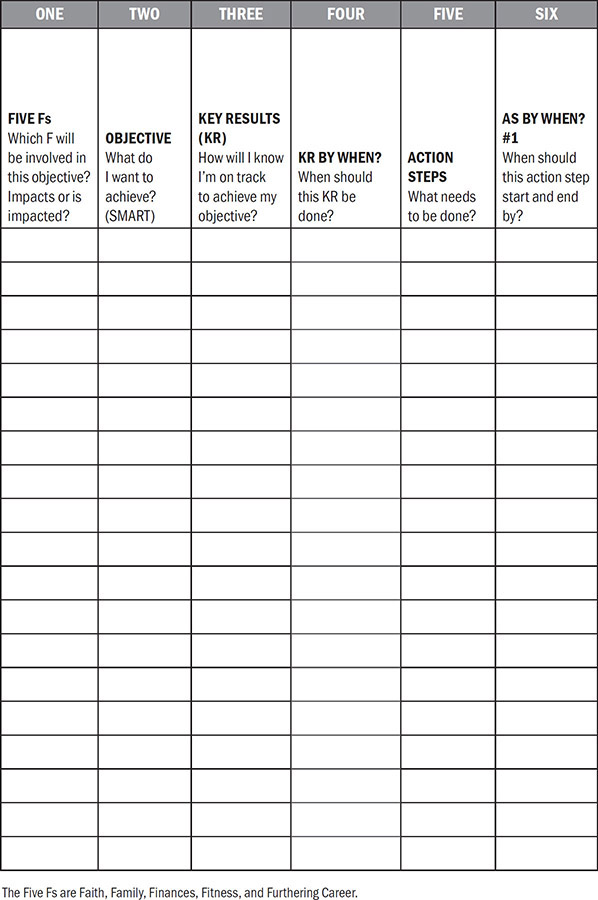

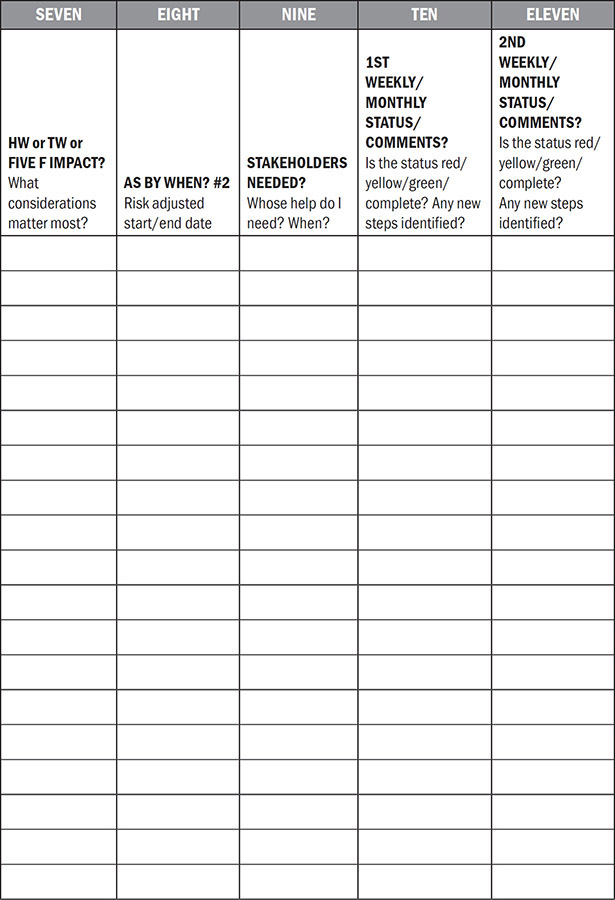

Now you can focus on completing the next column (Column 9) from your plan of action template, which you are already familar with. You can see that I have unshaded Columns 9 and 10 in Table 6.2. Use the stakeholder assessment and stakeholder map you just completed (Table 6.1 and Figure 6.1, respectively), and identify the key stakeholders (or other key resources) you believe will help you achieve that key result and put them into your POA, Column 9.

TABLE 6.2 Plan of Action—Status/Comments

As you look at those added names and timing, decide if you need to add any action steps for that key result to incorporate the stakeholders you are adding. If so, it is now you would risk-adjust the plan again with any changes to your dates, to ensure you are allowing time for actions you will take to connect with or influence those stakeholders.

Column 10 is for you to use as needed, in the way you will find helpful. I recommend you use it at least once every two weeks or upon key milestone achievements to capture your perspective on the status of your action steps. You can add another column(s), i.e., like Column 11, if you want to record even more of your key result and action step status as you go through your Iterate step. We’ll discuss that more in Step III.

You may find that you have a gap—the influencers/stakeholders you have access to may not be the right ones for your OKRs, or the ones you have may not be willing to help you to the degree you need, as in the case of Uma (in Chapter 5), who just knew she had those two sponsors to help get her promoted. Modify your POA to help you account for actions needed to feed, watch, check, or confirm your stakeholders. Columns 2, 4, 6, and 8 are the columns that really truly matter. Those contain the dates you are going after. Make sure those dates are solid, real, and risk adjusted. If you don’t hit your dates for your action steps (Columns 6 and 8), you may miss hitting your date for your key results (Column 4), which would impact your ability to achieve your SMART Objective (Column 2).

GETTING THE RIGHT STAKEHOLDERS INTO YOUR SPHERE OF INFLUENCE

Now that you know what the various stakeholder types are, determine what kind of stakeholders you currently have and what kind you need to win when people say you won’t. How do you get them? How can you find them, attract them, and be positively impacted by them? If you have the highly influential stakeholder that is not positively interested or in your corner, what do you do? If you have the positive kind that is in your corner, how do you engage? Let’s unpack these issues one at a time.

How to address the stakeholder gap? Just as you look at any other situation in your life, you look at your desired outcome, identify what stakeholders you need, and look at what resources and tools you have. The negative difference between what you have and what you need (meaning you have fewer positively impactful or influential stakeholders than you need) means you need to supplement your stakeholders with the right ones, and vice versa. You may not have a direct connection with a stakeholder, but someone you know certainly does.

I am coaching a young entrepreneur, Bantu, a former visual effects guru who worked on major movies such as Thor, Children of Men, The Revenant, Guardians of the Galaxy, and more. He has a game-changing software, intellectual property, and patents that will dramatically disrupt how we watch videos, play games, and shop. He met with me and asked me to get him ready to meet with VCs and angel investors so he could build up his inventory in the video library, sign on more customers, and scale. The people in his normal tribe were not easy to find, and they were not in the mood anyway to invest, given that much of filming and Hollywood studios were shut down due to Covid-19 in 2020. Revenue was not coming in as fast as it used to in the good old days before 2020. He needed access to new stakeholders to invest capital in his company, and I knew some people I could introduce him to. Some of my direct connections became his, and he was able to continue to generate capital for his business.

Keep your relationships current and authentic, and keep increasing your exposure to others, being authentically interested in them, and you will not need to know everyone to win; you’ll just need to know the people you already know. The people you already know will introduce you to other people you need to know. Just make it clear to your influencers what you need.

How can you attract stakeholders who are interested in you? The demand is there for people looking for people with your capabilities. Make yourself discoverable. We are in the age of the Great Resignation. The senior leaders of companies, hiring managers, and private equity and VCs are all looking for great people, great investments, and great companies. With that said, they will not just fall into your lap, at least not all the time. Be discoverable—on LinkedIn, in blogs you write, on podcasts you host or guest-speak on, in magazines you contribute to, and in events you go to—and drop some nuggets of wisdom that make people want to follow you and know who you are. That’s part pushing yourself and part networking. When you do that, people will hear about you, your circle of influencers will grow wider, and you will find you have multidimensional stakeholders that will be able to influence outcomes in multiple areas.

You may go directly to someone who is a role model of yours and let that person know you admire his or her work, or you admire some feature about the person, and ask if you can pick the person’s brain on something that you believe he or she knows about; or you may just want to glean some of the person’s general wisdom. It may take some scheduling, but that meeting—if you spend time listening to the person’s advice in the meeting and following up—can lead to that person being a mentor to you. And mentors can sometimes lead to sponsors.

If you are looking for capital for your new business, go to the SBA; go to the chamber of commerce; or ask friends who are entrepreneurs (surely you have at least one) how they got funded, if they can share their pitch deck with you, and if they can introduce you to any of the angels or VC folks. Your CFO or finance leader will likely know the big banks, which will in turn know smaller banks, which will in turn know companies that may invest in women or Black minority firms.

BUILD YOUR PLAN BY KNOWING WHO IS IN YOUR CORNER

It is said that “not everyone who is in your circle is in your corner.” There will be people who may not be supportive of you, but they may be highly influential to your success—or to your downfall. You may not always know their hidden intentions. You will need to know who your supporters and detractors are and ensure that you are aware of where and when they may affect your achievements. That’s the nature of competition, capitalism, the Olympics, the stock market. In the struggle to win, to matter, and to be great, there will always be folks on the other side. You will win even when you have people working against you, because you will look at competition and microaggressions as just noise, or as information that you can use to counter with planning, stakeholders, plans of action, and measures of success.

I was one of the highest-ranking African Americans in GE, and even though GE had given me a fancy car (a 640xi BMW), provided me high-profile assignments to lead global teams, and arranged audiences with the top 100 corporate officers in the company (one career level above me), that still didn’t prevent negative feedback from my detractors.

Being able to achieve in corporate America took more force, strength, cunning, and strategies for me than my white colleagues seemed to need. I understood that I looked different—I was “leading while Black”—and I had my share of casualties. I am a woman in a male-dominated industry, and I was Black in places where there were not many Blacks.

In one case, I was invited to a meeting with some vendors who wanted to sell me their services for software integration. I was running a bit late, and I walked into the conference room where the men were already seated. I said “Good afternoon, all . . . ,” but before I could continue, one of the men said, “I’m sorry, but you must be in the wrong room. We are waiting for the SVP, Daphne Jones.”

I said to the gentlemen, “And who do you think I am?” This situation is an example of how it is not always assumed that a Black person will be in a high position of power. By the very nature of some form of privilege, the man (and likely the others in the room) assumed the Black person walking in the room could not be Daphne Jones but someone who was in the wrong room. He didn’t ask first and clarify; he shot over the bow and felt foolish later. He didn’t know me, but years of supremacy and privilege allowed him to make a purely naïve statement, which let me know he was not “naturally” in my corner. The vendors at the meeting wanted my money, but they didn’t think I could have been Daphne. Because of their clear lack of preparation and other key business reasons, they didn’t get my business.

Sometimes you have to be willing to be a living example of the opposite of what people believe. Then one by one, they get to understand that not everyone with the same or different gender or race will match the stereotype. I encourage all of you to know who is in your corner so you can win.

I didn’t cry racism or sexism at every turn, but for leaders at my company who may have had less education or experience than me, but didn’t look like me, they just seemed to have an easier time to get funding, hire more employees, or gain access to key opinion leaders when they needed to. I had mentors, but I believe it was my ability to look at situations and define a plan that would help me through the roadblocks and win.

The need for support from stakeholders will never go away—and help is rarely given too soon. We all need help to win, so don’t be afraid to ask for it. No one, not even the president of the company, or the president of the United States, does everything alone. And these people still win.

When I was in college, I needed support. When I was a director in my forties and fifties, I needed support. As a new board member, I needed support. And as an experienced board member today, I still need support. Whether you are moving into middle management, thinking of going back to school, or starting your own company, you should always seek to identify your support system of stakeholders and ask them for their input on your journey.