Strategy

There are myriad definitions of strategy, ranging from that of General Sun Tzu, ‘Know your opponent,’ in the sixth century BC, to Kenichi Ohmae’s rather more recent interpretation, ‘In a word, competitive advantage.’

I am an economist, so I believe that we should bring the word ‘resources’ into the definition. Just as economics can be defined as the optimal allocation of a nation’s scarce resources, so we can define a company’s strategy thus:

‘Strategy is how a company deploys its scarce resources to gain a sustainable advantage over the competition.’

What your backer needs to know is how you plan to allocate your company’s resources over the business plan period to meet your goals. These resources are, essentially, your assets – your people, physical assets (for example, buildings, equipment and inventory) and cash (and borrowing capacity). How will you allocate – or invest – these resources to optimal effect?

More precisely, your backer needs to be convinced that your strategy will enhance your firm’s competitive position in key business segments.

You have already set out your firm’s competitive position in the section above. You even had a go at examining how that may change over time.

In this section, you must show how you can proactively improve that position through deployment of a winning business strategy. That is how you will provide strategic underpinning to your forecasts in Chapter 7 of your plan. That is how you will convince your backer to back you.

What is your company’s strategy? How will you deploy your scarce resources to gain a sustainable competitive advantage?

First, let’s look at the generic strategies.

Generic strategies

There are again many definitions of generic strategies, with each business guru seeming to come up with their own. But, in essence, and in the vast majority of cases, a company needs to choose between two very different and easy-to-grasp generic strategies: low-cost or differentiation.

Either generic strategy can yield a sustainable competitive advantage. Either the company supplies a product (or service) that is at lower cost to its competitors or it supplies a product that is sufficiently differentiated from its competitors that customers are prepared to pay a premium price – where the incremental price charged adequately covers the incremental costs of supplying the differentiated product.

For a ready example of a successful low-cost strategy, think of easyJet or Ryanair, where relentless maximisation of load factor enables them to offer seats at scarcely credible prices, compared with those prevailing before they gate-crashed the market, and still produce a profit. Or think of IKEA’s stylish but highly price-competitive furniture.

A classic example of the differentiation strategy would be Apple. Never the cheapest, whether in PCs, laptops or mobile phones, but always stylistically distinctive and feature-intensive. Or Pret A Manger in fresh, high-quality fast food. Or Lady Gaga with her outrageous flamboyance – a contemporary variant on Josephine Baker and her brazen banana costume.

One variant on these two generic strategies worth highlighting is the focus strategy, developed prominently by Michael Porter. While acknowledging that a firm can typically prosper in its industry by following either a low-cost or differentiation strategy, an alternative is not to address the whole industry but to narrow the scope and focus on a slice of it, a single segment. With such a focus, a firm can achieve market leadership through both differentiation and competitive pricing, having generated scale-driven low unit costs.

A classic example of a successful focus strategy is Honda motorcycles, whose focus on product reliability over decades yielded the global scale to enable its quality products to remain cost competitive.

Strengthening competitive position

Having clarified which generic strategy underpins your business, how are you planning to improve your competitive position over the plan period? How will you reinforce your competitive advantage?

The answer should lie in the analysis you have already done above when assessing your competitive position versus that of your competitors.

Against which key success factors did you rate less favourably than a key competitor? Is this an important, highly weighted KSF? Will it remain so in the future? Could it become even more important over time? Should this relative weakness be addressed?

Or should you instead be building on your strengths, widening an already existing gap between you and competitors in a particular KSF?

It is inadvisable to generalise, but, in theory, investment in building on strengths should offer a more favourable risk/reward profile than investing to address weaknesses.

If your generic strategy is one of low cost, what investments or programmes are you planning to reduce costs even further and so stay ahead of the competition? What major investments in plant, equipment, premises, staff, systems, training and/or partnering are you planning? What performance improvement programmes are underway or planned?

If your generic strategy is one of differentiation, what investments or programmes are you planning to reinforce that differentiation and make you stand out even more clearly than your competitors? What major investments in plant, equipment, premises, staff, systems, training, marketing and/or partnering are you planning? What strategic marketing programmes are underway or planned?

If your generic strategy is one of focus, what investments or programmes are you planning to reduce costs and/or reinforce your differentiation? What major investments, performance improvement or strategic marketing programmes are underway or planned?

How will these investments or programmes impact on your competitive position in key business segments? Your backer needs to know.

Essential tip

Whatever your firm’s competitive position in a key business segment today, it probably won’t be the same in three years’ time. Markets evolve, competitors adapt. Your firm needs to take control over its future. Convince your backer that your firm is proactively improving its competitiveness.

Boosting strategic position

So far, our analysis has been premised on the strengthening of your competitive position in your key product/market segments over the next few years.

But suppose you don’t have the resources, whether in cash, time or manpower, to do all you would like to do. How should you prioritise between the segments? Which investments or programmes should you do first? Which should be dropped, possibly forever? Which segments should you get out of?

You may benefit from undertaking a portfolio analysis. This will identify how competitive you are in markets ranked by order of attractiveness. You should invest ideally in segments where you are strongest and/or which are the most attractive. And you should consider withdrawal from segments where you are weaker and/or where your competitive position is not that good.

And, finally, should you be looking at entering another business segment (or segments) that is in more attractive markets than the ones you currently address? If so, do you have grounds for believing that you would be at least reasonably placed in this new segment, or that you could readily become reasonably placed?

This analysis will identify your strategic position. This is not to be confused with your competitive position, which relates to how competitive your company is in a particular product/market segment. Your strategic position relates to your balance of competitiveness across all segments, of varying degrees of attractiveness.

First, let’s be clear on what we mean by an ‘attractive’ market. The degree of market attractiveness should be measured as a blend of four factors:

- ■market size

- ■market demand growth

- ■competitive intensity

- ■market risk.

The larger the market and the faster it is growing, the more attractive the market is, other things being equal. But be careful with the other two factors, where the converse applies. The greater the competitive intensity in a market and the greater its risk, the less attractive it is.

You will have to use your own judgement on the weighting you apply to each of these factors. Simplest would be to give each of the four an equal weighting, so a rating for overall attractiveness would be the simple average of the ratings for each factor.

You may, however, be risk averse and give a higher importance to the market risk factor. In this case, you would need to derive a weighted average of each of the four ratings.

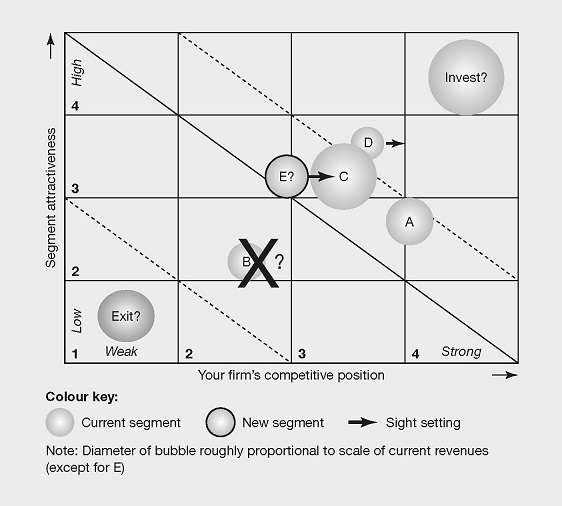

An example may help. Suppose your company is in four product/market segments and you are contemplating getting into a fifth. You draw up a strategic position chart, where each segment is represented by a circle (see Figure 5.1).

The segment’s position in the chart will reflect both its competitive position (along the x-axis) and its market attractiveness (along the y-axis). The size of each bubble should be roughly proportional to the scale of revenues currently derived from the segment.

The closer your segment is positioned towards the top right-hand corner, the better placed it is. Above the top right dotted diagonal, you should be thinking of investing further in that segment. Should the segment approach the bottom left dotted diagonal, however, you should consider exiting.

The strategic position shown in Figure 5.1 is sound. It shows favourable strength in the biggest and reasonably attractive segment C, and an excellent position in the somewhat less attractive segment A. Segment D is highly promising and demands more attention, given the currently low level of revenues.

Segment B should, perhaps, be exited – it’s a rather unattractive segment, and you’re not that well placed. The new segment E seems reasonably promising.

In developing a strategy for this example, you may consider the following worth pursuing:

- ■continued development in segments A and C

- ■investment in segment D (with the arrow showing the resultant improvement in competitive position)

- ■entry to segment E (with competitive position improving over time as market share develops)

- ■exit from segment B (crossed out in the figure).

How is your strategic position? Hopefully, your main segments, from which you derive most revenues, should find themselves positioned above the main diagonal.

Which segments are so important that you would derive greatest benefit from improving your competitive position? Where should you concentrate your efforts?

Do you have any new segments in mind? How attractive are they? How well placed would you be?

Are there any segments you should be thinking of getting out of?

One final word on strategic position. The above example showed the strategic position of a small company involved in five product/market segments.

Exactly the same analysis can and should be undertaken for a larger company involved in, say, five businesses – or strategic business units (SBUs, in management-speak). The bubbles of Figure 5.1 would now represent businesses, as opposed to segments.

Each business can be plotted against both competitive position (itself a weighted average of that business’s competitive position in each of its addressed segments) and market attractiveness (again a weighted average).

And the same conclusions could be drawn: invest in one business, hold another for cash, exit a third, and so on.

If you have plans for improving your strategic position, they should be in your business plan. Your backer needs to know.

Essential example

Reggae Reggae’s strategy

Reggae Reggae Sauce is a classic example of the success of test marketing. For many years, Jamaica-born reggae musician Levi Roots and his family set up a stall (named ‘Rasta’rant’!) at the Notting Hill Carnival in West London and sold jerk chicken to passing revellers. He received so many compliments about the sauce, made to his grandmother’s ‘secret recipe’, that he decided to bottle some in his kitchen and sell it separately. For this, he received backing of £1,000 from Greater London Enterprise. At the 2006 Carnival, these bottles flew off the stall as fast as the jerk chicken itself.

Encouraged, Roots took his bottles around various trade shows, marketing it innovatively by playing the guitar to a reggae beat and singing a song about the sauce. At one such show, he was spotted by a BBC producer and, a few months later, he reprised the song in front of 3 million viewers on the BBC’s Dragons’ Den. He walked away with an investment of £50,000 for 40% of his company in February 2007, a success attributable partly to his charisma and singing but, mainly, one suspects, to the proven success of the product. It had been test marketed again and again, on the streets, and found to be a winner.

The rest of the story is a phenomenon. The Dragons helped it get onto the shelves at Sainsbury’s, where it was expected to shift 50,000 units a year and ended up selling almost that amount in a week. Soon, the sauce range was extended, for example, with a Red Hot version, followed by a Reggae Reggae Cookbook, Reggae Reggae crisps, a Reggae Reggae pizza at Domino’s, a Reggae Reggae box meal at KFC, a Levi Roots Caribbean Crush drink, and so on.

Roots’s company is now valued at tens of millions of pounds, giving the Dragons one of their best ever returns and making Roots a very wealthy man. No wonder he has written a book titled You Can Get It If You Really Want!