5 Paradigm of Positive Peace

This chapter drills down to a more granular level on how the paradigm of Peace—especially Positive Peace—functions conceptually. Positive peace is a distinct concept indicating that violence of any kind is not used to achieve or maintain it. Three other dominant paradigms are also explored: Economic, Risk and Human Rights. Each of these paradigms already operates as a decision-making framework when MNEs and their employees make social and environmental business decisions. Although they are useful in making certain business decisions (e.g., health and safety, worker well-being, HR practices), they limit and preclude certain types of lateral thinking leading to innovative solutions to community-based social and environmental issues. Considered together with the paradigm of Positive Peace, this chapter demonstrates the advantages and disadvantages of each of the three dominant paradigms.

5.1 Overview

‘Positive Peace’ has only begun to emerge as a paradigm in the natural resources context. It has the potential to be a unifying paradigm to maximise outcomes, or it could be used alongside CSR paradigms, as defined in Chapter 4, in the NRC-community space. This chapter endeavours to show how and why positive peace could be conceptualised. First, ‘peace’ is described at the philosophical level. Next, peace-building is described and differentiated from positive peace and conflict transformation. Finally, positive peace is described paradigmtically with the potential to structure CSR strategies designed to handle community-level conflict in the natural resources context.

5.2 Peace

Peace and Conflict Theorists have a variety of ways of understanding ‘peace’. Despite the fact that philosophers, theologians, analysts and statespersons have long researched, written and orated passionately about the virtues of peace, a coherent and systematic “philosophy of peace” is still in its infancy (Webel, 2007, p. 4). Nevertheless, peace is as ubiquitous as conflict in everyday life (Boulding, 1987). Most people know what it is and what it is not in their own contexts and cultures.

The first task is to address the question: what does ‘peace’ mean? Peace is a concept that is culturally couched and notoriously difficult to define in a universal way. Galtung’s essay Social Cosmology and the Concept of Peace (1981) surveys both Oriental and Occidental conceptions of peace: Judaism, Christianity, Islam, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, the modern period, Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Japanese traditional religion and Chinese Confucian. The essay advocates for dialogue about ‘peace’ towards developing a richer understanding about what the term means. The essay acknowledges traditional cultures’ views of peace and invites those groups into the larger dialogue, but does not attempt to capture their views here. Notably, the essay emphasises the following idea: “the world is dynamic, so are peace concepts” (Galtung, 1981, p. 194). In other words, it is neither possible nor desirable to attempt the achievement of one universal, static definition of peace. The essay cautions occidental scholars and policy makers not to be content with ‘peace’ as equivalent to the bare minimum definition of the absence of war or violence (negative peace). Instead, occidental views should return to Aristotelian values where peace represents privileging the things that make for human thriving (Eudaimonia), such as adequate food, water, shelter, access to livelihoods and education (Biskowski, 1998; Brenes, 2009). Peace in this way is also a commitment to increased well-being, but not at the expense of the ‘other’. Peace highlights a focus on the combination of justice, prosperity, harmonious co-existence with your cultural reference group as well as with those external to it, peace of mind and a compassionate commitment to non-injury. It is not a system, concept or a program exported onto another as a form of ‘idea colonialism’.

John Paul Lederach has a compatible notion of peace to that understood by Galtung. However, he elevates some key elements that not covered in Galtung’s essay, including the role of conflict transformation in relation to the concept of peace-building.

Metaphorically, peace is seen not merely as a stage in time or a condition. It is a dynamic social construct … . [and] peacebuilding involves a wide range of activities and functions … . needed to transform conflict toward more sustainable, peaceful relationships

(Lederach, 1997, p. 20)

Peace is a practical way of life. As part of this definition of peace, there are certain kinds of thought and action processes necessary to envision and then act in accordance with elements necessary for a long-term, positive peace. In The Moral Imagination (2005), Lederach stresses the need to continuously ask questions about the status quo in order to discover new ways of addressing what seem like the same old problems, such as how to encourage peace. He says that a commitment to living out or building peace requires a creative imagination as well as technical skill. At times, it even “requires a worldview shift” in order to facilitate “social change and break cycles of violence” while still living within them (Lederach, 2005, pp. ix–x). Used here, a ‘worldview’ is equivalent to a paradigm (Gladwin, Kennelly, & Krause, 1995).

Violence as the opposite of peace is discussed in Chapters 1 and 2. Lederach adds a characteristic whereby violence results from disregard of human inter-relatedness instead of “taking personal responsibility [for relationships] and acknowledging relational mutuality” (Lederach, 2005, p. 35). The argument here is to see relationships as central to conditions of peace; beyond that, there needs to be a willingness to suspend judgement and search for the least common social denominator. People need to think about peace from the following frame:

live with a high degree of ambiguity … [while employing] paradoxical curiosity which approaches social realities with an abiding respect for complexity, a refusal to fall prey to the pressures of forced dualistic categories of truth, and an inquisitiveness about what may hold together in a seemingly contradictory social energies in a greater whole.

(Lederach, 2005, pp. 36–37)

The relationships that result from these processes are characterised by “openness and accountability, self-reflection and vulnerability, mutual respect, dignity, and the proactive engagement of the other” (Lederach, 2005, p. 42).

5.3 Peace-Building with Conflict Transformation

Peace-building processes of conflict transformation address cultural, structural or direct violence and result in positive peace. Peace-building processes are rarely linear; thus, scholars have developed a number of diagrams that can be used to describe the nonlinearity of peace-building processes, the stakeholders involved and ways to conceptualise this distinct way of thinking about engaging people and groups experiencing conflict in their relationships (Curle, 2000; Francis, 2010; Lederach, 1995, 1997; Miall, 2011 [2004]; Nelson, 2000; Parlevliet, 2009; Schirch, 2004). Peace-building processes are dynamic, as described below.

The crucial idea is to consider a peacebuilding strategy as an open, creative and dynamic process constituted by ongoing action and reflection. Instead of designing a peacebuilding strategy at the very beginning and then implementing it, a systemic strategy takes shape during the process itself … The idea is to leave enough space for defining the desired outcomes together with all relevant stakeholders during the process.

(Korppen, 2011, pp. 86–87)

This contemporary description of what peace-building entails is more expansive than earlier iterations of the concept.

The term ‘peace-building’ originated with the UN’s efforts to rebuild the international world order following World War Two. It originally described activities that helped States recover from armed conflict; establish a stable civil society and non-coercive governmental structures; and promote the model of a Western-style, liberal, democratic ideal. The UN’s definition at inception was this: “peace-building refers to activities aimed at assisting nations to cultivate peace after conflict”.1 The current OECD definition of peace-building reflects the original UN use of the term.

[Peace-building] includes activities designed to prevent conflict through addressing structural and proximate causes of violence,2 promoting sustainable peace, delegitimizing violence as a dispute resolution strategy, building capacity within society to peacefully manage disputes, and reducing vulnerability to triggers that may spark violence.

(Blum, 2011, p. 2)

Scholars within the discipline of International Relations have continued to expand the range and sweep of peace-building to encompass a wide variety of meanings and activities that include mitigation of both violent and non-violent conflict at local, State or inter-State levels (Bellamy, Williams, & Griffin, 2006).

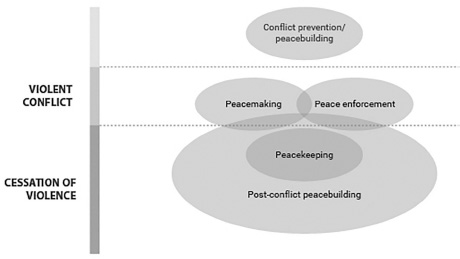

Peace-building is different from peacekeeping or peacemaking. Aall (2011) from the US Institute of Peace identifies peacekeeping as a United Nations-sanctioned activity authorised by the UN Security Council under Chapter 6 or 7 of the UN Charter. Peacekeeping allows for the use of light military force to either institute or preserve order in support of peacemakers, comprised of diplomats and mediators who are engaged with disputants in negotiations to stop hostilities. Peacekeeping is generally not an activity associated with natural resources unless in a militarised zone, such as when an NRC calls on the state militia to intervene in a community-NRC conflict. In such instances, the state works with the NRCs on security issues, but the state is ultimately charged with the overall responsibility of co-ordinating that effort even if the NRCs hire their own security forces. Peacemaking typically refers to diplomatic activity with the goal of stopping open, armed conflict and achieving either a cease-fire or broad negotiated settlements (Aall, 2011). Furthermore, the ‘order’ peacemakers are aiming for is typically liberal, supporting the reformation or creation of a social-democratic state. It is based on achieving a limited or negative peace which is “based on the fragile equation of state interests, issues and resources, and often depends upon external guarantors” (Richmond, 2010, p. 18). The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations unit (UNDPKO) represents the relationship between these terms and activities in Figure 5.1.

Peace-building includes a suite of activities involving actors from civil society, the business sector and advocacy groups (Jeong, 2000). These actors employ a wide range of strategies: helping disputants identify core and peripheral issues, assisting disputants in their own design of jointly held goals for both the short and long term and teaching disputants an ongoing mutual engagement process imbued with the qualities of integrity, non-violence and fairness. This book builds on the idea that peace-building strategies can be successfully expressed at the local level—even and perhaps especially when a conflict has not yet become physically violent. It is Galtung, Jacobsen and Brand-Jacobsen’s (2002) and Lederach’s (2003) perspective on the local applicability of peace-building activities which serves as further inspiration towards investigating their relevance in the NRC-community space.

Physical violence only breaks out in a minority of natural resource project sites around the world in any given year. However, most natural resource projects experience a range of less-violent yet still significant community-based conflicts at some point in their development or operation. Although positive peace and peace-building processes of conflict transformation are relevant in both sets of conflicts, this book is concerned with the larger group of non-physically violent NRC-community conflicts. Policy, NGO and research groups have covered physical violence, and natural resources are covered extensively elsewhere (cf. Amnesty International, IISD, UNDP).

This book proposes that NRCs are already employing versions of peace-building strategies to handle conflict with communities where both sustained and episodic, non-violent conflict is underway. However, the companies often do not label those activities as ‘peace-building’. This book suggests that these activities might yield greater results understood within a paradigm of positive peace. Strategies and processes such as community consultation (Amat y León & Velarde, 2005), Free-Prior-Informed-Consent (Martin, 2007), Mine Development Agreements (Gibson & O’Faircheallaigh, 2010), participatory water monitoring (Atkins, 2008) and similar are consistent with peace-building strategies and an overall paradigm of positive peace.

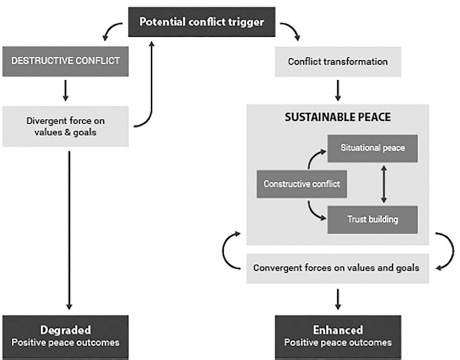

Figure 5.2 represents a conceptual model for conflict transformation in this book, with the starting place as the ‘Potential conflict trigger’:

In other words, when there is a potential conflict trigger on an economic, risk or Human Rights aspect related to natural resources, the choice in peace-building terms becomes whether or not to respond to the conflict as a destructive force or a constructive opportunity for conflict transformation.

If two or more parties start with a potential conflict trigger and respond to it as a destructive conflict, the relationship between the parties to that conflict grows progressively confrontational. This potentially leads to increasingly polarised positions that separate the parties even further from agreeing on how to address the conflict. In those opposing positions, it is difficult to address conflicts successfully. This downward spiral leads to degraded positive peace outcomes.

Alternately, if parties respond to a potential conflict trigger as an opportunity for constructive change—for conflict transformation—the outcomes look much brighter. Conflict transformation emphasises the relationship between the parties as important to the overall conflict outcomes possible. In handling a conflict constructively, parties build trust and strengthen contextual/situational peace based on converging values and goals. The upward spiral results in enhanced or optimised positive peace outcomes.

Positive peace is not a static ‘end goal’ however. There are instances where parties handle a conflict is positively and positive peace outcomes are optimised, but then something happens or changes. Whether there is an incident, an argument between parties, a shift in previously agreed opinions—a potential conflict trigger again emerges. To prevent conditions of positive peace from degenerating into another destructive, the parties need to re-engage the process of conflict transformation. The reapplication of the process has potential to take a destructive conflict cycle and re-route the parties back towards a constructive cycle.

However, strategies and processes for practical steps towards creating conditions of peace are not enough. There also needs to be a focus on the quality of the relationship between parties. In From Pacification to Peacebuilding (2010), Francis proposes that the primary condition of positive peace is the cultivation of a particular quality of relationship between parties. Relationship quality is critically important to NRCs and communities. When relationships are conducive to peace, it means that they are not coercive or violent in nature. They may be intensively persuasive, but there is no underlying or overt use of force to maintain the integrity of the relationship.

Francis’s argument is that there are two ways to view the world and that these opposing worldviews affect how people will enter into relationships. The way people look at relationships belongs in one of two categories: a view that privileges the idea of interdependence and mutual need or a view that sees life as a competition.

Peacebuilding, as understood through conflict transformation, begins from the worldview in which interdependence is the point of departure, orientating [sic] people and institutions towards peacebuilding as cooperation, while the worldview that sees life as a matter of eating or being eaten leads to … ‘pacification’.

(2010, pp. 73–74)

The long-term benefit of the interdependence worldview is the focus on the quality, mutuality and continuity of a relationship needing adjustment in response to any number of conflicts during its life. The long-term benefit of the eat-or-be-eaten worldview can also result in the cessation of conflict, but control and violence are options to be exercised while people in the process are considered expendable instruments, useful only insofar as they help achieve goals. Applied in the context of natural resources, where natural resource leases may run anywhere from ten to 100 years, the ‘long-term’ view emphasises looking at the entire life-cycle of a relationship between an NRC and a community in addition to valuing the achievement of shorter-term goals. These two worldviews are represented Table 5.1 as ‘positive peace’ and ‘negative peace’, respectively.

|

Positive Peace |

Pacification or Negative Peace |

|---|---|

|

NOTION OF PEACE |

|

|

• Just relationships, mutual care. Shared economic and political power and responsibility. • Demilitarised world. Constructive conflict culture and systems. • Planet as home. |

• Stability and hegemony. Top-down control, political and economic. • Strong military as guarantor of control. • Planet as resource to exploit |

|

APPROACH TO INTERNATIONAL REGULATION |

|

|

• Principled and democratic (participatory) |

• Conditional and instrumental |

|

APPROACH TO CONFLICT AND CHANGE |

|

|

• Multi-level, bottom-up work; work of and in support of local actors • Nonviolent, constructive; achieving just outcome for all • Conflict Resolution to address human needs |

• Top-down, hegemonic, interventionist • Military pacification ‘if necessary’ in own interest. • Win-lose orientation • Conflict Resolution to avoid destabilisation |

|

APPROACH TO POWER, REALITY, PROCESS/OUTCOME, PEOPLE |

|

|

• Power as capacity to achieve things cooperatively • Process and outcome inseparable • All people are subjects and no one is expendable |

• Power as ability to dominate • Process and outcome separate • Some people are instruments and may be expendable |

|

VALUES |

|

|

• Common good • Respect and care for all |

• Own success • Respect for power ‘us’ and ‘them’ |

|

NOTION OF SECURITY |

|

|

• Interdependent |

• Dominate or be dominated |

(Table adapted from “From Pacification to Peacebuilding” Francis, 2010, p. 74)

This book privileges Francis’s recommendation for genuine peace-building rather than for pacification as the perspective from which to evaluate the potential to achieve positive peace in the NRC-community space. History has repeatedly shown that when NRCs and their supporters, which sometimes include government bodies, prefer practices of ‘pacification’, such as the more metaphorically muscular, financially or legally persuasive methods of engaging conflict, then NRC-community conflict is not resolved in the long term and often results in recurring negative outcomes throughout the lifecycle of an NRC operation. Examples of these methods can be found in early community engagement activities at the Cerrejon mine in Colombia (Bond, 2009; Ringwood, 2011), where there was violent and forced resettlement, and in the history of mining at multiple sites in Indonesia, where environmental hazards were created that destroyed livelihoods, waterways and ecosystems (Ballard, 2001). Conversely, when mining companies and communities have chosen practices synchronous with long-term, non-violent peace-building methods, there has been greater success in realising acceptable outcomes from conflicts experienced during the lifecycle of a mine (Bichsel et al., 2007). Examples of these methods can be found in scholarship about the Tintaya Mesas de Dialogo in Peru (Barton, 2005; Echave, Keenan, Romero, & Tapia, 2004) and promising recent developments at the Three Gorges Dam in China (Wilmsen, 2016).

Finally, peace-building is an activity that can and does take place before, during and after a conflict of whatever size (Alger, 1999; Boulding, 2000; Graf, Kramer, & Nicolescou, 2007; Lederach, 2005; Vayrynen, 1999). Therefore, conflict transformation practices can intentionally create the conditions for positive peace by prevention as well as by helping disputants engage current conflicts or the aftermath of conflicts. This is because peace-building works at the cultural, structural and social levels of two or more groups who are experiencing conflict about opposed positions, interests and needs (Miall, 2011 [2004]). Since conflicts are always within distinct social environments, this chapter advances the idea that the social environmental context of NRC-community relationships is fertile ground for exploring how aspects of peace-building would improve the outcomes of those types of conflicts for all parties involved.

Admittedly, the history of natural resources projects in the 20th century alone reveals a legacy littered with outcomes that are not peaceful, such as involuntary resettlement, waterway pollution, significant health effects, poor labour conditions, grave environmental impacts, changing the contours of landscapes significant to Indigenous peoples and more. Communities in the Global South has borne the brunt of these effects. Consequently, it will become increasingly important for the 21st-century natural resources industries to develop the will and a holistic strategy towards both addressing these negative legacies and natural resources responsibly into the future. Peace-building practices of conflict transformation have potential to provide a vehicle by which to achieve these goals in co-operation with communities to deal constructively with the root causes of conflict and work on mending or improving relationships. Positive peace, then, is the endpoint towards which the transformation work is aiming and moving.

5.4 Positive Peace Paradigm

It is not enough to understand how the literature represents positive peace; it is also important to suggest a bridge towards practice. Paradigms could be that bridge between theory and practice, as well as being the potential foundation for CSR strategies. This section defines positive peace, describes a Positive Peace paradigm and evaluates what it offers as similar to and different from the three alternate CSR paradigms discussed in this chapter. The most distinctive difference is that a Positive Peace paradigm can incorporate other CSR paradigms, leading to improved conflict outcomes and less violence overall.

Following both Galtung and Lederach, a paradigm of positive peace is less about prescribing actions or listing a series of culturally or policy specific ‘shoulds’ and ‘should nots’ and more about cultivating an attitude both at the individual and at the group level. Positive peace focuses on outcomes beneficial to all because the process at arriving at those outcomes is inclusive, mutually co-created between stakeholders and retains mutual kindness at its core. The Positive Peace paradigm is different from the ‘liberal peace’ paradigm fashionable in international relations circles for the last 20 or more years (Chapter 3). “The liberal peace paradigm, views the development of democracy both as a goal of state-building and as a means to induce conflict transformation” (Galvanek & Mubashir, 2012, p. 81). In other words, liberalism equates democracy as a necessary pre-condition for peace. Zaum summarises the following characteristics:

Across the literature, liberal peacebuilding has been used to describe external peacebuilding interventions that share several characteristics: first, they are conducted by liberal, Western states; second, they are motivated by liberal objectives such as responding to large-scale human rights violations or being conducted under an international responsibility to protect; and third, these interventions promote liberal-democratic political institutions, human rights, effective and good governance, and economic liberalization as a means to bring peace and prosperity to war-torn countries. Since the end of the Cold War, most peacebuilding operations have been characterized by a commitment to the promotion of these liberal values and institutions.

(Zaum, 2012, pp. 121–122)

Zaum follows this description, citing major works by MacGinty and Richmond, to survey the relative lack of success of attaining peace or peaceful societies in periods following violent conflict and peacekeeping interventions, e.g., Cote d’Ivoire (ca. 2004) and Timor L’Este (ca. 1999). There are reasons for this failure: “the approach is laden with inherent contradictions, misses the specific socio-economic challenges of post-conflict countries, and exacerbates social and economic inequalities through marginalization and increased vulnerability to poverty” (Peace-building Initiative, 2009). Zaum concludes his comments on the liberal peace by saying that it does not sufficiently incorporate local culture or encourage local participation. Instead, he recommends looking at instances where peace-building has been successful. They have the structure of a hybrid peace, rather than a strictly liberal peace (Chapter 4).

As an alternative, scholars have begun exploring a hybrid peace as the preferred post-liberal concept of positive peace, as in Hybrid Forms of Peace: from everyday agency to Post-Liberalism (Richmond & Mitchell, 2012). In this volume, and in a related conference paper, hybrid forms of peace incorporate both international norms but also local customs (2012; Boege & Curth, 2011). Local customs are not unitary, nor are they static—they are constantly in flux. Additionally, they are inclusive of a wide variety of stakeholders, such as traditional authorities, women, group leaders or chiefs, affected community members as well as representatives from various levels of government. Finally, hybrid peace processes cannot be rushed according to political cycles or particularly Western standards of timeliness. The hybrid peace concept, and related peace-building practices, may have more potential than a liberal peace. Hybrid peace may indeed be useful to international actors, such as MNEs, who are in relationship with a wide variety of stakeholders in situations where natural resource company- community conflict is likely to emerge.

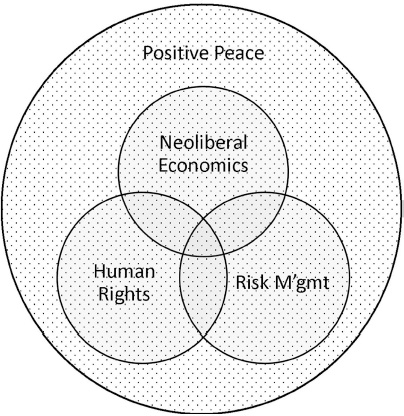

With an understanding of a Positive Peace paradigm, we now look at how to link the paradigm of positive peace to CSR. This book explores whether the paradigm of positive peace can function in one of two ways. The first way is to incorporate the other three CSR paradigms: Neoliberal Economic, Risk Management and Human Rights. Following the work of Masterman (1970) and Kuhn (1977), positive peace does not seek to supplant them but to provide a foundational paradigm that can prioritise and shape the use of the tools and frameworks that otherwise belong to the three influential paradigms described in the preceding chapter. They could ideally operate within an overall paradigm of positive peace (see Figure 5.3).

As an example of Masterson’s reading of Kuhn, this construction conceptualises the relationship between the paradigms with positive peace in the following ways. In terms of the Economic paradigm, International Alert published that

Peacebuilding … needs to be a comprehensive transformative process: … not as an adjunct to economic growth, but rather the function of economic growth in conflict contexts. It is also a process that intimately involves the private sector because of its core function in the economy.

(2006, p. 78)

Regarding risk management, if violence and its outcomes can generally be seen as putting communities and businesses at risk in a variety of ways, then the use of peace-building processes—which, throughout the scholarship on peace, is resolutely focused on reducing and eliminating violence—can reduce those risks and improve the outcomes of using risk-based frameworks and toolkits. Finally, peace is inclusive of Human Rights: “elements in the culture of peace paradigm … propose the replacement of hierarchical structures with equality values, understanding, tolerance, and human rights” (Fry, Bonta, & Baszarkiewicz, 2009, p. 24). Positive peace highlights a commitment to increased well-being, but not at the expense of the ‘other’, softening aspects of the Human Rights paradigm that can sometimes prioritise one person or groups rights over another’s. The most unique aspect of the paradigm of positive peace is its ability to hold in creative tension the sometimes competing energies of the Neoliberal Economic, Risk Management and Human Rights paradigms in a way that prioritises finding non-violent or non-coercive solutions to those ambiguities and tensions.

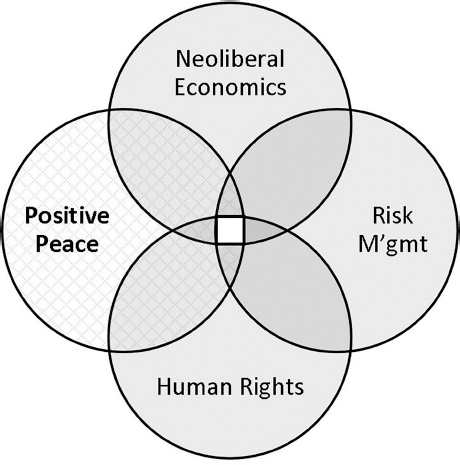

A second, perhaps more convincing, way to conceptualise the relationship between the paradigm of positive peace and the other three paradigms is that they operate in an overlapping way. For practical purposes, different stakeholders within the NRC-community nexus will approach a conflict situation from within their own preferred paradigm. A CSR practitioner acting from within a Positive Peace paradigm would need to encourage processes and solutions that are acceptable to individuals operating from within these different paradigms (see Figure 5.4).

In this construction, the goal would be to find and enlarge the ‘sweet spot’ (yellow circle, at the centre) to support the relationship between the paradigms as described in the preceding paragraph. This ‘sweet spot’ would necessarily look different for each unique natural resources-company community conflict situation because they each have different characteristics. This construction, perhaps more so than the first one, would prioritise an emphasis on the quality of relationship between the parties as a central concern. An improved relationship would then increase opportunities to generate productive outcomes, including a combination of all four paradigms. Moreover, this model would allow more clearly for the consideration of other potential paradigms.

Comparing the two constructions suggests that they are both valid but at different times in a conflict cycle. The potential disadvantage of the first construction is that all parties to a conflict would have to agree—up front—that conditions of positive peace were jointly shared by all. In the heat of a conflict situation, this may not be possible, whereas it could be possible during an agreement-making period between an NRC and a community, as a statement of a goal held in common. A much larger program of research would need to be undertaken of NRC-community conflicts to test how these conceptualisations work in practice and with which CSR and/or peace-building methods. Within the scope of this book, however, it is enough to explore the degree to which a paradigm of positive peace has traction with CSR practitioners to determine whether it is feasible to pursue that larger program of research.

5.5 Why Make the Connection Between Positive Peace and CSR?

One purpose of exploring the paradigm of positive peace as a potential foundation for CSR strategies is to see if it can increase productive conflict outcomes. The word ‘productive’ refers to a range of beneficial conflict outcomes for most if not nearly all stakeholders in an NRC-community relationship. In business terms, Parker, Alstine, Gitsham and Dakin (2008) suggest that the word productive refers to value creation such as employee retention, increased NRC operational outputs and reduced human resource costs. Adding a social responsibility dimension to Parker et al.’s (2008) definition, the word ‘productive’ might also usefully refer to increased benefits for natural resources-affected communities. These benefits include but are not restricted to improved quality of life, infrastructure development, health care, education and training.

The word ‘productive’ has also had particular meaning in the peace and conflict literature since the mid-1950s. Three scholars highlight the term’s positive aspects. Putnam (1994) summarises the inherent dynamism that characterises productive conflict between two or more stakeholders (in the citation below: ‘groups’) in the following way:

Intergroup conflict is often characterized by an increased flow in communication between and within groups. Through engaging in controversy with another group, both groups can enhance their understanding of complex problems, broaden their perspectives on organizational life, and develop a foundation to manage differences.

(Putnam, 1994, p. 285)

In other words, for a conflict to be productive means that it can harness the dynamic energy generated between stakeholders to achieve improved performance while co-creating innovative outcomes and solutions that would not be possible even in a static, harmonious, inflexible relationship. Bowman (2001) agrees and advances this position by suggesting that a conflict-free relationship leads to poor decision-making and sub-optimal outcomes for all parties. Respected peace scholar Schirch uses the analogous distinctions ‘constructive’ and ‘destructive’ to qualify the nature of conflicts in Strategic Peacebuilding (2004). She defines a constructive (productive) conflict as capable of addressing the needs of all involved and a destructive conflict as one in which communication has irretrievably broken down and violence is either immanent or active. Importantly, neither Putnam nor Bowman nor Schirch suggest that addressing conflict is either comfortable or easy to engage in a productive/constructive way. Nor do these authors advocate intentionally causing, manipulating or engineering circumstances of discontent to achieve an outcome. However, each cites a significant body of literature to indicate that productive/ constructive conflict, as opposed to unproductive/destructive conflict, has the potential to result in acceptable outcomes for the majority if not all parties who were engaged in the process.

In this book, then, the term ‘productive’ is preferred both for the scholarly reasons mentioned above but also because there is almost always an expectation of tangible material, financial and social outcomes from natural resources activities sought by both NRCs and communities. Examples include: generating positive cash flow, reducing organisational risk, maintaining or improving valuable aspects of a community’s status quo in terms of socio-cultural heritage, employment opportunities and improved infrastructure. Table 5.2 illustrates this and compares productive conflict to its inverse.

The term ‘unproductive’ includes various forms of exclusion (as above) which have the consequence of diminishing how productive a conflict outcome can be considered, overall. If marginalised groups such as women, children, the elderly, Indigenous or disabled groups from a community are intentionally or unintentionally either partially or fully omitted from a conflict engagement process, then the capacity for that process to be considered productive is reduced by the measure that vulnerable people are under-represented in the process (Colchester & Ferrari, 2007; ICMM, 2010; Rio Tinto, 2010). Under-representation of marginal people increases the potential for negative outcomes for the parties who actually did engage in the process, no matter what side(s) of the conflict they were or are on (Martin, 2007). Increased negative outcomes (1) result from the process by which a conflict was handled and (2) affect the overall NRC-community relationship, diminishing the prospect for achieving positive peace. Examples of these negative outcomes can include: disease, unchecked in-migration, alcohol, drugs, sexual violence, environmental damage and cultural rupture. Each one of these symptoms of unproductive processes can become a conflict trigger.

|

Productive/Constructive Conflict |

Unproductive/Destructive Conflict |

|---|---|

|

Engagement of majority and minority groups throughout consultation and decision-making processes |

Exclusion of women, elderly, children, Indigenous or marginalised groups from consultation or decision-making |

|

Focus on long-term relationship building strategies that include short-term goals |

Focus on short-term financial or production results with little to no long-term view |

|

Intentional co-design of dispute resolution processes shared by company-community |

Ad hoc or unilateral design of dispute resolution processes acted upon by one party at the expense of the other party |

|

Mutually agreed outcomes (i.e. financial, material, social, cultural) |

Predetermined outcomes set by one party without consulting the other party |

|

High value placed on clear communication and the time necessary for it to occur |

Communication channels have broken down; violence is immanent or active |

|

Relationship between parties is dynamic, flexible, characterised by mutual regard and innovation |

Relationship between parties is static, inflexible or even artificially harmonious |

Consistent with Richmond’s (2010) fourth generation of Peace and Conflict Theory, a productive conflict successfully engages majority and minority group views from the design of the conflict engagement process through to the conclusion of the particular conflict situation between the parties. It also has the potential to improve the quality of the relationships between the local parties/groups and addresses the underlying issue(s) causing the conflict while contributing to the social, environmental and economic goals of the parties involved. Underlying a productive conflict engagement process from start to finish is the acknowledgement by all parties that any isolated instance of conflict is only one incident in a series of conflict encounters in the life of their relationship. The parties therefore recognise the iterative process regarding the way particular instances of conflict are handled can and will shape the ongoing relationship between the parties—setting up the initial conditions for how participants will view each other and the subsequent conflict. As in Figure 5.5, this iterative process can either result in a downward spiral that leads to greater frequency and more violent expressions of conflict, or it can result in an upward spiral that leads to the dynamic conditions of positive peace. The spiral can be represented alternately, as seen in the diagram.

When a conflict engagement process is productive, transformative and by nature participatory, it is also peace-building (Richmond, 2010). Looking at conflict as a transformative opportunity rather than a threat is an intentional stance. Within the paradigm of positive peace, conflict is not seen only as a negative occurrence but, if handled properly, an occasion for positive change (Eurich, 2006). Lederach emphasises the following:

Conflict is an opportunity, a gift … . Conflict can be understood as the motor of change, that which keeps relationships and social structures honest, alive and dynamically responsive to human needs, aspirations and growth.

(Lederach, 2003, p. 18)

Lederach sees relationships and social structures as the locations where conflicts happen but also where peace is forged. His focus on relationships rather than on the content of any one conflict between parties allows the envisioning of a different future while finding a way to respond to a current conflict through constructive rather than destructive change (Lederach, 2003).

5.6 Conclusion

Although scholars and resource sector professionals have long recognised that natural resources activities often either precipitate or re-awaken conflict with and within proximate communities (Epps, 2003; Kemp, Owen, Gotzmann, & Bond, 2011; Zandvliet & Anderson, 2009), they have only begun to explore the potential for natural resources to contribute to ongoing conditions of peace at the community level as described in the second chapter on the literature linking business and peace. This book contributes to this newer body of knowledge by considering the NRC-community interface as a relatively new frontier for the application of peace practices and future peace research. In the next chapter, research data is presented and analysed to explore the level of traction a paradigm of positive peace could have in the CSR space in the natural resources context. Because a paradigm of positive peace is not directly linked to the use of legal means or threats and eschews physical, cultural or structural violence, it is uniquely suited to encouraging the development of peaceful relationships and outcomes from conflict between NRCs and communities.

Notes

Bibliography

Aall, P. (2011). Peace terms: Glossary of terms for conflict management and peacebuilding. Washington, DC: USIP.

Alger, C. F. (1999). The expanding tool chest for peacebuilders. In H.-W. Jeong (Ed.), The new agenda for peace research. Ashgate: Sydney, Australia.

Amat y León, R. F., & Velarde, E. (2005). Building stakeholder engagement through consultation. Peru: Tintaya.

Atkins, D. (2008). Participatory Water Monitoring: A guide for preventing and managing conflict. Washington, D.C.: IFC.

Ballard, C. (2001). Human rights and the mining sector in Indonesia: A baseline study. England: MMSD.

Barton, B. (2005). A global/local approach to conflict resolution in the mining sector: The case of the Tintaya dialogue table (Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Thesis), Tufts University, Boston, MA.

Bellamy, A., Williams, P., & Griffin, S. (2006). Understanding peacekeeping. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Bichsel, C., Dalby, S., Dama, A., Hagmann, T., Maurer, P., & Shiferaw, M. (2007). Environmental peacebuildling: Managing natural resource conflicts in a changing world. Bern, Switzerland: Swiss Peace.

Biskowski, L. J. (1998). Reason in politics: Arendt and Gadamer on the role of the eide. Polity, 31(2), 217–244.

Blum, A. (2011). Improving peacebuilding evaluation: A whole-of-field approach.Washington, D.C.: USIP.

Boege, V., & Curth, J. (2011). Grounding the responsibility to protect: Working with local strengths for peace and conflict prevention in the Solomon Islands. Paper presented at the ISA Asia Pacific Conference, The University of Queensland, School of Political Science and International Studies.

Bond, C. J. (2009). Land, sacred sites and mining: Constructing dialogue to reduce conflict between transnational mining companies and indigenous/rural peoples. (Master of International Studies, Adv. (Peace Studies & Conflict Resolution)), University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Boulding, E. (2000). Cultures of peace: the hidden side of history. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Boulding, E. (1987). Learning peace. In R. Vayrynen, D. Senghaas, & C. Schmidt (Eds.), The quest for peace. London: Sage.

Bowman, R. F. (2001). Temptation #4: Harmony versus productive conflict. The Educational Forum, 65(3), 221–226.

Brenes, A. (2009). Personal transformations needed for cultures of peace. In J. de Rivera (Ed.), Handbook on building cultures of peace. New York, NY: Springer.

Colchester, M., & Ferrari, M. F. (2007). Making FPIC—free, prior and informed consent—work: Challenges and prospects for indigenous peoples. Moreton-in-Marsh, UK: Forest People’s Program.

Curle, A. (2000). Obstacles to peace. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 6(3), 247–252.

Echave, J. D., Keenan, K., Romero, M. K., & Tapia, Á. (2004). Dialogue and management of conflicts on community lands: The case of the Tintaya mine in Peru. Peru: CooperAccion.

Epps, J. M. (2003). Managing the social risk of mining. Paper presented at the Mining Risk Management Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Eurich, H. (2006). Factors of success in UN Mission communication strategies in post-conflict settings: A critical assessment of the UN Missions in East Timor and Nepal. Berlin: Logos Verlag.

Francis, D. (2010). From pacification to peacebuilding: A call to global transformation. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fry, D. P., Bonta, B. D., & Baszarkiewicz, K. (2009). Learning from extant cultures of peace. In J. de Rivera (Ed.), Handbook on building cultures of peace. New York, NY: Springer.

Galtung, J. (1981). Social cosmology and the concept of peace. Journal of Peace Research, 18(2), 183–199.

Galtung, J., Jacobsen, C., & Brand-Jacobsen, K. F. (2002). Peace: The goal and the way. In J. Galtung, C. Jacobsen, & K. F. Brand-Jacobsen (Eds.), Searching for peace. London: Pluto Press.

Galvanek, J. B., & Mubashir, M. (2012). Reflections on the CORE workshop: The potential of norms for conflict transformation. In J. B. Galvanek, H. J. Giessmann, & M. Mir (Eds.), Norms and premises of peace governance (Vol. 32, pp. 18–24). Tubingen: Berghof Peace Support and Institute for Peace Education.

Gibson, G., & O’Faircheallaigh, C. (2010). IBA community toolkit: Negotiation and implementation of impact and benefit agreements. Toronto: Walter & Duncan Gordan Foundation.

Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J., & Krause, T-S. (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. The Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 874–907. doi:10.2307/258959

Graf, W., Kramer, G., & Nicolescou, A. (2007). Counselling and training for conflict transformation and peace-building. In C. Webel & J. Galtung (Eds.), Handbook of peace and conflict studies. London, UK: Routledge.

ICMM. (2010). Good practice guide: Indigenous peoples and mining. London.

International Alert. (2006). Local business and the economic dimensions of peacebuilding. -London: International Alert.

Jeong, H. -W. (2000). Peace and conflict studies. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Kemp, D., Owen, J. R., Gotzmann, N., & Bond, C. (2011). Just relations and company— community conflict in mining. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(1), 93–109.

Korppen, D. (2011). Space beyond the liberal peacebuilding consensus—a systemic perspective. In D. Korppen, N. Ropers, & H. J. Giessmann (Eds.), The non-linearity of peace processes. Farmington Hills, MA: Barbara Budridge Verlag.

Kuhn, T. A. (1977). Second thoughts. The essential tension. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lederach, J. P. (1995). Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. Washington, DC: United States Institute for Peace.

Lederach, J. P. (2003). The little book of conflict transformation. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Lederach, J. P. (2005). The moral imagination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Martin, S. (2007). Free, prior and informed consent: The role of mining companies. Victoria: Oxfam.

Masterman, M. (1970). The nature of a paradigm. In I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave (Eds.), Criticism and the growth of knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miall, H. (2011 [2004]). Conflict transformation: A multi-dimensional task. In B. Austin, M. Fischer, & H. J. Giessmann (Eds.), Advancing conflict transformatoin: The Bergof handbook II. Framington Hills, MA: Barbara Budrich.

Nelson, J. (2000). The business of peace. London: International Alert.

Parker, A. R., Alstine, J. V., Gitsham, M., & Dakin, R. (2008). Managing risk and maintaining license to operate: Participatory planning and monitoring in the extractive industries.

Parlevliet, M. (2009). Rethinking conflict transformation from a human rights perspective. Berlin.

Peacebuilding Initiative. (2009). Economic recovery: Key debates and implementation challenges. New York, NY. Retrieved from www.peacebuildinginitiative.org/index2ed1.html?pageId=1907

Putnam, L. L. (1994). Productive conflict: Negotiation as implicit coordination. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 5(3), 284–298.

Richmond, O. (2010). A genealogy of peace and conflict theory. In O. Richmond (Ed.), Palgrave advances in peacebuilding. London: Palgrave.

Richmond, O., & Mitchell, A. (Eds.). (2012). Hybrid forms of peace: From everyday agency to post-liberalism. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ringwood, C. (2011). Afro-Colombian resistance in La Guajira. Counter Punch, 18 July 2011. Retrieved from http://www.counterpunch.org/2011/07/18/afro-colombian-resistance-in-la-guajira/

Rio Tinto. (2010). Why gender matters: A resource guide for integrating gender considerations into communities work at Rio Tinto. Melbourne.

Schirch, L. (2004). The little book of strategic peacebuilding. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

UNPKO. (2008). United Nations peacekeeping operations principles and guidelines. New York, NY: United Nations.

Vayrynen, R. (1999). From Conflict Resolution to Conflict Transformation: A Critical Review. In H.W. Jeong (Ed.), The New Agenda for Peace Research (pp. 135–160). Sydney, Australia: Ashgate.

Webel, C. (2007). Introduction. In C. Webel & J. Galtung (Eds.), Handbook of peace and conflict studies. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wilmsen, B. (2016). After the Deluge: A longitudinal study of resettlement at the Three Gorges Dam, China. World Development, 84, 41–54.

Zandvliet, L., & Anderson, M. B. (2009). Getting it right: Making corporate- community relations work. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Zaum, D. (2012). Beyond the “Liberal Peace”. Global Governance, 18, 121–132.