11

Sample Business Plan for a Fictional Company

The sample business plan in this chapter shows the forecasts and cash flows for a company planning to produce three films. Due to space considerations, it is not practical to include separate business plans for both a single film and a company plan. They both follow the same format, but with some modifications. All of the costs for a one-film plan should be included in the budget, and summary tables are not necessary. Of course, the reader also has to modify the text that is shown in the book to relate to one film. For more information and detail on how to create the forecasts and cash flow, please refer to the “Financial Worksheet Instructions” on the companion website for this book.

If you plan on accessing a state or country film incentive, include it after the section on Strategy but before Financial Assumptions. Tax incentives for films are not included in the sample business plan. Whether in the United States or other countries, incentives change on a regular basis. In some cases, they may be discontinued altogether or simply run out of funds to apply for after a period of time. Be sure to tell investors to check with their own tax advisors to see how a specific incentive would affect them. In addition, do not subtract potential incentives from your total budget. In the case of most U.S. state incentives and many of those in other countries, there is an accounting done by the governing body at the end of production before the actual dollars are awarded. The statement that you qualify for an incentive is not a guarantee on the amount of money you will receive.

Sample Business Plan For:

Crazed Consultant Productions

This document and the information contained herein are provided solely for the purpose of acquainting the reader with Crazed Consultant Productions and are proprietary to that company. This business plan does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This business plan has been submitted on a confidential basis solely for the benefit of selected, highly qualified investors and is not for use by any other persons. By accepting delivery of this business plan, the recipient acknowledges and agrees that: (i) in the event the recipient does not wish to pursue this matter, the recipient will return this copy to Business Strategies at the address listed below as soon as practical; (ii) the recipient will not copy, fax, reproduce, or distribute this confidential business plan, in whole or in part, without permission; and (iii) all of the information contained herein will be treated as confidential material.

| CONTROLLED COPY | For Information Contact: |

| Issued to: ___________ | [Name] |

| Issue Date: ___________ | c/o [Company name] |

| Copy ___________ | [Address] [Phone] [Email] |

Table of Contents

- 1 / The Executive Summary

- 2 / The Company

- 3 / The Films

- 4 / The Industry

- 5 / The Market

- 6 / Distribution

- 7 / Risk Factors

- 8 / The Financial Plan

1 / The Executive Summary

Strategic Opportunity

- North American box office revenues in 2015 were $11.1 billion

- Revenues for independent films in 2015 were $2.9 billion

- Worldwide box office revenues were $38.3 billion for 2015.

- Box office revenues worldwide are projected by PricewaterhouseCoopers to be $48.1 billion in 2019.

The Company

Crazed Consultant Productions (CCP) is a startup enterprise engaged in the development and production of motion picture films for theatrical release. The first three films will be based on the Leonard the Wonder Cat books by Jane Lovable. CCP owns options on all three with two books already in print and a third currently being written. The books have sold 25 million copies in 12 countries. The movies based on Lovable’s series will star Leonard, a half-Siamese, half-American shorthair cat, whose adventures make for entertaining stories, and each of which includes a learning experience. The movies are designed to capture the interest of the entire family, building significantly on an already established base. CCP expects each film to stand on its own as a story.

The Company plans to produce three films over the next five years, with budgets ranging from $500,000 to $10 million. At the core of CCP are the founders, who bring to the Company successful entrepreneurial experience and in-depth expertise in motion picture production. The management team includes President and Executive Producer, Ms. Lotta Mogul; Vice President/CFO, Mr. Gimme Bucks; and Producer, Ms. Ladder Climber.

The Films

- Leonard’s Love: Natasha and her cat Leonard leave the big city to live in a small town, where they discover the true meaning of life.

- Len’s Big Thrill: Leonard charms the director during Natasha’s audition for a movie and becomes a bigger star than Uggie the dog.

- Leonard and Buffy Go to Camp: Leonard discovers a scam by the director at an acting camp for cats. Will he and Buffy expose the swindle and reignite their acting careers?

The Industry

The future for low-budget independent films continues to look impressive, as their commercial viability has increased steadily over the past decade. Recent films such as Finding Mrs. Feline, Yak Outa Mongolia, and My Big Fat Siamese 1 and 2 are evidence of the strength of this market segment. The independent market as a whole has expanded dramatically in the past 15 years, while the total domestic box office has increased 45 percent. Proof of the high quality of indies is that an independent film has won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 10 of the last 11 years.

Widely recognized as a “recession-proof” business, the entertainment industry has historically prospered even during periods of decreased discretionary income. As studios cut back, equity investors have been moving into the independent film arena. Technology has dramatically changed the way films are made, allowing independently financed films to look and sound as good as those made by the Hollywood studios, while remaining free of the creative restraints placed upon an industry that is notorious for fearing risks. There also is evidence, however, that being digitally connected helps to drive theater receipts. “Word of mouth no longer exists,” Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) chief Christopher Dodd said. “It’s now word of text.”

The Markets

Family films appeal to the widest possible market. Films such as Me and My Doberman, The Lone Maltese, and The Hungry Sphynx Cat franchise have proved that the whole family will go to a movie that they can see together. For preschoolers, there are adorable animals, while tweens and teens get real-life situations and expertly choreographed action, and parents enjoy the insider humor. The independent market continues to prosper. As an independent company catering to the family market, CCP can distinguish itself by following a strategy of making films for this well-established and growing genre.

Distribution

The motion picture industry is highly competitive, with much of a film’s success depending on the skill of its distribution strategy. As an independent producer, CCP aims to negotiate with major distributors for release of their films. The production team is committed to making the films attractive products in theatrical and other markets.

Investment Opportunity and Financial Highlights

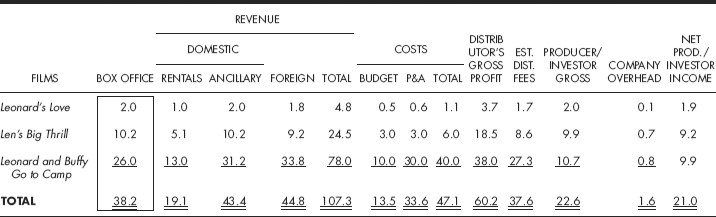

CCP is seeking an equity investment of approximately $47.1 million for development and production of three films and an additional $1.6 million for overhead expenditures. Using a moderate revenue projection and an assumption of general industry distribution costs, we project (but do not guarantee) gross worldwide revenues of $107.3 million, with pretax producer/investor net profit of $21 million.

2 / The Company

CCP is a privately owned California corporation that was established in September 2011. Our principal purpose and business are to create theatrical motion pictures. The Company plans to develop and produce quality family-themed films portraying positive images of the household cat.

The public is ready for films with feline themes. Big-budget animal-themed films have opened in the market over the past five years. In addition, the changing balance of cat to dog owners in favor of the former is an allegory for changes in society overall. The objectives of CCP are as follows:

- To produce quality films that provide positive family entertainment with moral tales designed for both enjoyment and education.

- To make films that will celebrate the importance of the household cat and that will be exploitable to a mass audience.

- To produce three feature films in the first five years, with budgets ranging from $500,000 to $10 million.

- To develop scripts with outside writers.

There is a need and a hunger for more family films. We believe that we can make exciting films starting as low as $500,000 without sacrificing quality. Until recently, there was a dearth of cat films. We plan to change the emphasis of movies from penguins, pigs, and dogs to cats, while providing meaningful and wholesome entertainment that will attract the entire family. In view of the growth of the family market in the past few years, the cat theme is one that has been undervalued and, consequently, underexploited.

Production Team

The primary strength of any company is in its management team. CCP’s principals Lotta Mogul and Gimme Bucks have extensive experience in business and in the entertainment industry. In addition, the Company has relationships with key consultants and advisers who will be available to fill important roles on an as-needed basis. The following individuals make up the current management team and key managers.

Lotta Mogul, Executive Producer

As Executive Producer, Lotta Mogul will oversee the strategic planning and financial affairs of the Company. She previously ran Jeffcarl Studios, where she oversaw the production and distribution of over 15 films. Among her many credits are Lord of the Litter Box, The Dog Who Came for Dinner, Fluffy Goes to College, and the Feline Avengers franchise, which earned more than $600 million. Before moving into film, Mogul was Vice President of Marketing at Lendaq, an American multinational corporation that provides Internet-related products and services.

Gimme Bucks, Producer

With 10 years experience in the entertainment industry, Gimme Bucks most recently produced the comic-action-thriller Swarm of Locusts for Forthright Entertainment. He made his directorial debut on Cosmic Forces, which Wondergate is releasing in 2013. Bucks also has been a consultant to small, independent film companies.

Better Focus, Cinematographer

Better Focus is a member of the American Society of Cinematographers. He was Alpha Numerical’s director of photography for several years. He won an Emmy Award for his work on Unusual Birds of Ottumwa, and he has been nominated twice for Academy Awards.

Ladder Climber, Co-Producer

Ladder Climber will assist in the production of our films. She began her career as an assistant to the producer of the cult film Dogs That Bark and has worked her way up to production manager and line producer on several films. Most recently, she served as a line producer on The Paw and Thirty Miles to Azusa.

Consultants

Samuel Torts, Attorney-at-Law, Los Angeles, CA; Winners and Losers, Certified Public Accountants, Los Angeles, CA

3 / The Films

Currently, CCP controls the rights to the first three Leonard the Wonder Cat books by Jane Lovable. The books will be the basis for its film projects over the next five years. In March 2014, the Company paid $10,000 for three-year options on each of the first three books and first refusal on the next three. The author will receive additional payments over the next four years as production begins. The Leonard series has been obtained at very inexpensive option prices due to the author’s respect for Lotta Mogul’s devotion to charitable cat causes. Three film projects are scheduled.

Leonard’s Love

The first film will be based on the novel Leonard’s Love, which has sold 10 million copies. The story revolves around the friendship between a girl, Natasha, and her cat, Leonard. The two leave the big city to live in a small town, where they discover the true meaning of life. Furry Catman has written the screenplay. The projected budget for Leonard’s Love is $500,000, with CCP producing and Ultra Virtuoso directing. Virtuoso’s previous credits include a low-budget feature, My Life as a Ferret, and two rock videos, Feral Love and Hot Fluffy Ragtime. We are currently in the development stage with this project. The initial script has been written, but we have no commitments from actors. Casting will commence once financing is in place. As a marketing plus, the upcoming movie will be advertised on the cover of the new paperback edition of the book.

Len’s Big Thrill

Natasha is an actress in her late thirties still trying to get her big break in Hollywood. She lives in a small one bedroom in Marina del Rey. On a good day, she can see the ocean if she stands on the furthest corner of her narrow balcony. Her closest companion is her cat, Leonard. He has been through many auditions with Natasha, quietly sitting on the sidelines while she tries for that big break. To make matters worse, Natasha has just gotten a final notice to pay her rent or be evicted.

One day in September, Len accompanies Natasha while she auditions for yet another movie role. Getting the lead in this movie would solve her current financial problems. Restless with the wait at the audition, Leonard struts across the room. Seeing the cameraman, he looks directly into the camera and appears to smile. The director, Simon Sez, is captivated by Len’s natural ease in front of a camera. He thinks the cat actually is posing. Then he gives the cat some stage directions—run across the room, jump on the chair, and pretend to sleep—that Leonard appears to follow. The cameraman, Wayne, doesn’t believe it. He points out to Simon that household cats are hard to train and seldom follow verbal directions from a stranger.

When Natasha reads for her role, Simon is equally captivated by her. He wants to make a deal for both Natasha and Leonard to be in the film, but Natasha is hesitant. Simon explains that he wants to rewrite the script to feature Leonard as the cat who saves his mistress from a burning building. After years of waiting for her big break, Natasha feels that he wants to hire her only to get Leonard into the film. In addition, she thinks that Simon may be one of those directors who is more interested in a one-night stand than with her acting talent. Natasha declines the part for both of them and leaves the studio with her cat.

Simon refuses to give up. He sends flowers and calls every day. When serious attempts don’t work, he tries humor. One day a fellow dressed as a Siamese cat shows up at the door with a singing telegram. The song, written by Simon, is from another cat begging her to let him play with Leonard on the set. On another day, UPS delivers a box of movie posters showing both Natasha and Leonard posing in front of a burning building. The posters are accompanied by fake online reviews about the “new” actress, Natasha, who is sure to win an Academy Award for Best Actress. Then, he has former girlfriends call her to extol his virtues and guarantee that he is one of the good guys. Finally, he calls and invites her for coffee to discuss the project.

The coffee business meeting turns into lunch that turns into dinner. Natasha realizes that she is attracted to this man; however, she worries that having a relationship with him may just be her own desire for the movie part and the paycheck. Simon assures her that his intentions are honorable. He suggests that they put any personal relationship on the back burner so that she will feel comfortable. He says that she was the best actress to test for the part. Leonard’s antics would add that much more to the film. He is willing to go with the original script if Natasha wants. After thinking about it for a week, Natasha decides to go ahead with the film including the cat’s part.

Despite Wayne’s misgivings, Len is a natural in front of the camera. Although they hire a trainer for him, he prefers to follow Natasha’s requests. As a true Siamese, he doesn’t like commands. The film is a smash with audiences. Walking the red carpet turns out to be one of Len’s favorite activities. Finally realizing they are in love, Natasha and Simon marry, giving Len the biggest thrill of all.

Leonard and Buffy Go to Camp

The third book in the series is currently being written by Lovable and will be published in late 2018. The story features a dejected Leonard whose films aren’t drawing the audiences they used to. His ice skating career had ended before he got out of juniors competition. Being a cat, he tried something no one had ever done―a quintuple jump―and fell. He sees no future. Desperate to get him out of his doldrums, his mother suggests a summer acting camp for cats. “You did get good reviews in those Hallmark dramas,” she tells him. Since going to camp is better than sitting around the house with a lot of nagging, he agrees to go.

Arriving at camp, he finds himself in a cabin with five other males, all relatively quiet American shorthairs. Being a Siamese, he immediately is king of the pack. When everyone gathers for dinner that night, he sees his old friend Buffy sitting at the female felines’ table. The other tomcats notice her, also. Leonard decides to catch up with her later rather than create rude purring from his new group.

At dinner, camp director Elena Leopardine gives a welcome and runs down the activities for the rest of the week. They will have acting seminars in the morning and take advantage of activities in the afternoon, such as art (scratching landscapes onto chair material, making lanyards with yarn, and painting by paw, swimming (treading water in the pool and floating in the lake) and fishing (diving into the lake for fish for dinner).

As several days go by, Leonard notices that no matter how well they do the scenes in acting class, Leopardine keeps making them repeat. He complains when he has to redo a yodel meow 56 times and is made to sit in the corner while the others take a break to lap some milk. Sneaking over to the feline’s cabin, he calls out to Buffy with a code they developed in Hollywood―two purrs, a yowl, and four hisses repeated three times. She comes out putting her paw to her mouth to keep him quiet. They compare notes and learn that both are going through the same grueling process with no time off for the activities.

The next day, annoyed and feeling that Leopardine is hiding something, he convinces his counselor, Herman Himalayan. While Leopardine is at the local spa getting her weekly beautifying regimen, the two of them with Buffy and her counselor, Angela Angora, sneak into Leopardine’s cabin. They find emails between her and producer Brian Gorzilla discussing the film she is current shooting at the camp. Leopardine has been doing all the retakes to make a film without telling them or planning to pay any of the cat actors.

Buffy taps out an email to her father, an entertainment lawyer. While everyone is in class, the police arrive to arrest Leopardine for breaking cat labor laws and committing several felonies. The camp owner, who knew nothing about Leopardine’s plans, invites the cats to spend the rest of the summer doing the activities and sitting in the sun. With a true Hollywood ending, Gorzilla likes the scenes so much that he pays Buffy and Leonard to finish the film; and their careers take off again!

4 / The Industry

The future for independent films continues to look impressive, as their commercial viability has increased steadily over the last two decades. Recent films such as Finding Mrs. Feline, Yak Outa Mongolia, and My Big Fat Siamese 1 and 2 are evidence of the strength of this market segment. The independent market as a whole has expanded dramatically in the past 15 years, while the total domestic box office has increased 45 percent. Proof of the high quality of indies is that an independent film has won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 10 of the last 11 years.

As studios cut back, equity investors have been moving into the independent film arena. Lately, falling salaries, rising subsidies, and a thinning of competition have weighted the financial equation even more in favor of the investor. In addition, revolutionary changes in the manner in which motion pictures are produced and distributed are now sweeping the industry, especially for independent films.

The total North American box office in 2015 was $11.1 billion. The share for independent films of the total was $2.9 billion. Worldwide box office revenues were $38.3 billion in 2015. Domestically, ticket sales rose 8 percent in 2015, while admissions jumped 4 percent to 1.32 billion. Two-thirds of the population of U.S. and Canada, some 235.3 million people, went to the movies at least once last year, a 2 percent increase from 2014.

At CinemaCon 2016, the CEO of MPAA, Christopher Dodd, and CEO of the National Association of Theater Owners, John Fithian, cited diverse audiences and the preservation of theatrical windows as key reasons for the growth. “I’m proud to say that the state of our industry has never been stronger,” Dodd told the crowd. He also suggested that three quarters of frequent moviegoers own at least four different types of technology products such as smartphones, tablets, and video game systems, and this helped to drive box office receipts. “Word of mouth no longer exists,” he said. “It’s now word of text.”

In its 2015–2019 Global Entertainment and Media Outlook, PricewaterhouseCoopers projected a total worldwide box office of $448.1 billion by 2019. Once dominated by the studio system, movie production has shifted to reflect the increasingly viable economic models for independent film. The success of independent films has been helped by the number of new production companies and smaller distributors emerging into the marketplace every day, while major U.S. studios maintain divisions dedicated to providing distribution in this market segment. Investment in film continues to be an attractive prospect despite economic instability. Widely recognized as a “recession-proof” business, the entertainment industry has historically prospered even during periods of decreased discretionary income.

Motion Picture Production

The structure of the U.S. motion picture business has been changing over the past three decades, as studios and independent companies have been creating varied methods of financing. Although those companies historically funded production totally out of their own arrangements with banks, they now look to partner with other companies, both in the U.S. and abroad, that can assist in the overall financing of projects. The deals often take the form of domestic companies retaining the rights for distribution in all U.S. media, including theatrical, home video, television, cable, and other ancillary markets.

Major studios, the largest companies in this business, include NBC Universal (owned by Comcast Corp.), Warner Bros. (owned by Time Warner), Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation (owned by Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox), Paramount Pictures (owned by Viacom), Sony Pictures Entertainment, and The Walt Disney Company. MGM, one of the original Majors, was taken private in 2010 and now functions as an independent that both partners with other studios and finances its own movies. In most cases, the “Majors” own their own production facilities and have a worldwide distribution organization. With a large corporate hierarchy making production decisions and a large amount of corporate debt to service, the studios aim most of their films at mass audiences.

Producers who can finance films independently by any source other than a major U.S. studio have more flexibility in their creative decisions, with the ability to hire production personnel and secure other elements required for pre-production, principal photography, and post-production on a project-by-project basis. With substantially less overhead than the studios, independents are able to be more cost-effective in the filmmaking process. Their films can be directed at both mass and niche audiences, with the target markets for each film dictating the size of its budget. Typically, an independent producer’s goal is to acquire funds from equity partners, completing all financing of a film before commencement of principal photography.

How It Works

There are four typical steps in the production of a motion picture: development, pre-production, production, and post-production. During development and pre-production, a writer may be engaged to write a screenplay or a screenplay may be acquired and rewritten. Certain creative personnel, including a director and various technical personnel, are hired, shooting schedules and locations are planned and other steps necessary to prepare the motion picture for principal photography are completed. Production commences when principal photography begins, and generally continues for a period of not more than three months. In post-production, the film is edited, which involves transferring the original filmed material to digital media in order to work easily with the images. Additionally, a score is mixed with dialogue, and sound effects are synchronized into the final picture and visual effects are added. The expenses associated with this four-step process for creating and finishing a film are referred to as its “negative costs.” A master is then manufactured for duplication of release prints for theatrical distribution and exhibition, but expenses for further prints and advertising for the film are categorized as “P&A” and are not part of the negative costs of the production.

Theatrical Exhibition

There were 43,661 theater screens (including drive-ins) in North America in 2015, per the most recent “Theatrical Market Statistics” report released by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). Film revenues from all other sources are often driven by the North American domestic theatrical performance. The costs incurred with the distribution of a motion picture can vary significantly depending on the number of screens on which the film is exhibited. Although studios often open a film on 3,000 to 4,000 screens on opening weekends (depending on the budget of both the film and marketing campaign), independent distributors usually tend to open their films on fewer screens. Theatrical revenues, or “box office,” are often considered an engine to drive sales in all other categories. Not only has entertainment product been recession-resistant domestically but also the much stronger than expected domestic theatrical box office has continued to stimulate ancillary sales, such as home video and digital, as well as raising the value of films in foreign markets.

Television/Cable

Television exhibition includes over-the-air and wired reception for viewers, either through “free television” (national and independent broadcast stations) or a fee system (cable). The proliferation of new cable channels since the early 1990s has made cable (both basic and premium stations) one of the key revenue streams for feature films, surpassing broadcast network television over the last 20 years as the dominant “second screen” outlet for movies. “Basic” cable channels carry a broad range of programming, including licensed feature films and original and syndicated productions. “Premium” cable networks, such as HBO, Showtime, and Starz, require an additional subscription fee in exchange for commercial-free programming that includes licensed theatrical features, documentaries, and original series. Competing with cable companies are direct broadcast satellite (DBS) services, including DirecTV and Dish, which allow subscribers to watch programming via individual satellite dishes installed at their homes. Another group of providers are telecommunications companies, including Verizon’s FiOS and AT&T’s U-verse, that use Internet Protocol (IP) technology to beam cable channels into homes. All these systems acquire their film programming by purchasing the distribution rights from motion picture distributors. Pay-per-view (PPV) allows cable, satellite, or telecom subscribers to purchase individual films or special events, adding to the revenue stream for features.

Home Entertainment

In 2015, overall consumer spending on home video totalled $18 billion, up almost 1 percent compared to $17.8 billion in 2014, according to the Digital Entertainment Group (DEG). This reverses a downward trend over the last three years. Although total disc sales fell 12 percent during 2015 to come in at $6.1 billion, Blu-ray disc sales were up 8 percent in the three-month period between Oct. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015. Among other highlights for 2015 are:

- Electronic sellthrough generated $1.9 billion in consumer spending, up 18.1 percent from the $1.6 billion in 2014.

- Total consumer spending on digital—streaming, sales, and video-on-demand (VOD)—came in at an estimated $8.9 billion, a 16.4 percent increase from 2014. This number is driven by Netflix and SVOD, which some analysts feel should be considered separately.

- Subscription streaming of movies and TV shows generated consumer spending of more than $5 billion, a 25 percent gain from 2014. Home Media Magazine adds that tech publications and websites have said that in addition to playing high-definition discs, Blu-ray disc players double as the best streaming devices.

- Consumer sales of 4K Ultra HD TVs increased a dramatic 287 percent in the fourth quarter of 2015. Household penetration is now at more than 5 million U.S. households.

International Theatrical Exhibition

Much of the projected growth in the worldwide film business comes from foreign markets, as distributors and exhibitors keep finding new ways to increase the boxoffice revenue pool. More screens in Asia, Latin America, and Africa have followed the increase in multiplexes in Europe, but this growth has slowed. The world screen count is predicted to remain stable over the next eight years. Other factors include the privatization of television stations overseas, the introduction of DBS services, and increased cable penetration. The synergy between international and local product in European and Asian markets is expected to lead to future growth in screens and box office.

Future Trends

Revolutionary changes in the manner in which motion pictures are produced and distributed are now sweeping the industry, especially for independent films. Web-based companies like Google Play, Amazon’s Video on Demand, Apple’s iTunes Store, Vudu, and CinemaNow (now owned by FilmOn) are renting and selling films and other entertainment programming for download on the Internet and through their apps. Subscription websites and apps such as HBO GO, Showtime Anytime, Netflix, and Hulu Plus stream filmed entertainment to home viewers. Streaming platform Vimeo launched its on-demand service in 2013, and now has a growing number of titles available for rent or purchase via Internet or mobile app. Streaming media players, such as those made by Google, Roku, Amazon, Apple TV, and Sony, as well as the streaming features of Xbox (360 and Xbox One) and Wii, allow even those who are not tech savvy to stream content from these and similar websites directly to their HDTV screen, creating a home theatre experience. Multi-use portable devices that can provide personal viewing of films (including video iPod, smartphones, and tablets) are flooding the marketplace, expanding the potential revenues from home video and other forms of selling programming for viewing. These new technologies, and others not yet devised, will grow in influence in the next five years and in the longer term as well.

5 / The Market

The independent market continues to prosper. The strategy of making films in well-established genres has been shown time and time again to be an effective one. Although there is no boilerplate for making a successful film, the film’s probability of success is increased with a strong story, and then the right elements—the right director and cast and other creative people involved. Being able to greenlight our own product, with the support of investors, allows the filmmakers to attract the appropriate talent to make the film a success and distinguish it in the marketplace.

CCP feels that its first film will create a new type of moviegoer for these theaters and a new type of commercial film for the mainstream theaters. Although we expect Leonard’s Love to have enough universal appeal to play in the mainstream houses, at its projected budget it may begin in the specialty theaters as the blockbuster Sylvester Barks at Midnight did. Because of the low budget, exhibitors may wait for our first film to prove itself before providing access to screens in the larger movie houses. In addition, smaller houses will give us a chance to expand the film on a slow basis and build awareness with the public.

Target Markets

Family-Friendly Films

Family-friendly films appeal to the widest possible market, with Leonard’s Love and its sequels having a multigenerational audience from tweens to grandparents. Variety and industry websites have said that family films boost the box office. John Fithian, President of the National Association of Theater Owners, said, “Year after year, the box office tells an important story for our friends in the creative community. Family-friendly films sell.” Previously thought of only as kids’ films, family-friendly movies now offer a new paradigm of family entertainment. Production and distribution companies know that wholesome entertainment can be profitable. “Movies that have a good message for [young people] that adults enjoy are universally embraced,” says Tom Rothman of Twentieth Century Fox.

Cat Owners

The two most popular pets in most Western countries have been cats and dogs, with cats outnumbering dogs in 2015, according to a study by the American Pet Products Manufacturers. In the United States, there are 85.8 million pet cats compared to 77.8 million pet dogs. The statistics reveal that 54.4 million households own at least one pet dog compared to 42.9 that own cats. This seeming contradiction is due to the fact that the average household with a cat owns at least two. The study also shows that 65 percent of households (79 .7 million) currently own a pet.

The time has finally come for the cat genre film. Felines have been with us for 12 million years, but they have been underappreciated and underexploited, especially by Hollywood. Recent studies have shown that the cat has become the pet of choice. We plan to present domestic cats in their true light, as regular, everyday heroes with all the lightness and gaiety of other current animal cinema favorites, including dogs, horses, pigs, and bears. As the pet that is owned by more individuals than any other animal in the United States, a cat starring in a film will draw audience from far and wide. In following the tradition of the dog film genre, we are also looking down the road to cable outlets. There is even talk of a cat television channel.

CCP plans to begin with a $500,000 film that would benefit from exposure through the film festival circuit. The exposure of our films at festivals and limited runs in specialty theaters in target areas will create awareness for them with the general public. In addition, we plan to tie-in sales of the Leonard books with the films.

Demographics

Moviegoers of All Ages

The Leonard films are designed to appeal to everyone from children to their grandparents. It plays to younger ages better than many animated films, while still bringing in the whole family demographic. The MPAA counts all moviegoers from ages 12 to 90 in specific groups in their “Theatrical Market Statistics” analysis for 2015. Children ages 2 to 11 were 13 percent of total moviegoers; teenagers and young adults comprised 47 percent of the audience; and adults over 40 comprised the other 40 percent.

The moviegoers dubbed “tweens” (ages 8 to 12) have emerged as a force at the box office during the past several years. According to a survey by Marketing Sherpa, the buying power of this group is $200 billion. Since the MPAA’s audience data groups ages 2 to 11 together, we can’t present a separate audience percentage for children and tweens. Market research by upsidebusiness.com also shows that tweens like movies, video games, collectibles, books, and dolls. They also like to spend time talking to their friends on mobile phones and communicating through social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube.com, Nick.com, and WebKinz.com.

Social Media and Self-Marketing

An important marketing component for any film, especially during its opening weekend, is word-of-mouth. Without incurring additional costs, it is possible for the filmmakers and their many colleagues to supplement the marketing strategy of a distribution company by working through niche channels to spread word-of-mouth about the film. Integral to this approach are social networks. Facebook had 1.6 billion active users as of January 31, 2016, according to the company’s annual report. Another current favorite method of communication for business is Twitter, which had 310 million active users as of March 31, 2016. Twitter has become a force in the success of many films, as actors and other creative artists “tweet” about their participation, sometimes adding photos taken behind-the-scenes, at publicity events or premieres, and so on. Rank-and-file fans share the URLs of news stories about favorite films and artists, blog reviews on their own web pages, or even make video recordings of their reactions and post these to YouTube, their own sites or a social networking page. Then tweet the link to their followers, thus informing friends and web surfers about a film and influencing their opinions. On both Facebook and Twitter, fans chat to each other about highly anticipated films and make general declarations in status updates and tweets about their interest. eMarketer reports that social networking has become an “integral” and “routine” part of American lives.

6 / Distribution

The motion picture industry is highly competitive, with much of a film’s success often depending on the skill of its distribution strategy. The filmmakers’ goal is to negotiate with experienced distribution companies in order to seek to maximize their bargaining strength for a potentially significant release. The filmmakers feel that Crazed Consultant Production’s films have the potential to be an attractive product in this active marketplace with all distributors seeking good product.

Distribution terms between producers and distributors vary greatly. A distributor looks at several factors when evaluating a potential acquisition, such as the uniqueness of the story, theme, and the target market for the film. Since distribution terms are determined in part by the perceived potential of a motion picture and the relative bargaining strength of the parties, it is not possible to predict with certainty the nature of distribution arrangements. However, there are certain standard arrangements that form the basis for most distribution agreements. The distributor will generally license the film to theatrical exhibitors (i.e., theater owners) for domestic release and to specific, if not all, foreign territories for a percentage of the gross box office dollars. The initial release for most feature films is U.S. theatrical (i.e., in movie theaters). For a picture in initial release, the exhibitor, depending on the demand for the movie, will split the revenue derived from ticket purchases (“gross box office”) with the distributor; revenue derived from the various theater concessions remains with the exhibitor. The percentage of boxoffice receipts remitted to the distributor is known as “film rentals” and customarily diminishes during the course of a picture’s theatrical run. Although different formulas may be used to determine the splits from week to week; on average, a distributor will be able to retain about 50 percent of total box office, again depending on the performance and demand for a particular movie. In turn, the distributor will pay the motion picture producer a negotiated percentage of the film rentals less its costs for film prints and advertising.

Film rentals become part of the “distributor’s gross,” from which all other deals are computed. As the distributor often re-licenses the picture to domestic ancillaries (i.e., cable, television, home video), foreign theatrical and ancillaries, these monies all become part of the distributor’s gross and add to the total revenue for the film in the same way as the rentals. The distribution deal with the producer includes a negotiated percentage for each revenue source; e.g., the producer’s share of foreign rentals may vary from the percentage of domestic theatrical rentals.

The basic elements of a film distribution deal include the distributor’s commitment to advance funds for distribution expenses (including multiple prints of the film and advertising) and the percentage of the film’s income the distributor will receive for its services. Theoretically, the distributor recoups his expenses for the cost of its print and advertising expenses first from the initial revenue of the film. Then the distributor will split the rest of the revenue monies with the producer/investor group. The first monies coming back to the producer/investor group generally repay the investor for the total production cost, after which the producers and investors split the money according to their agreement. However, the specifics of the distribution deal and the timing of all money disbursements depend on the agreement that is finally negotiated. In addition, the timing of the revenue and the percentage amount of the distributor’s fees differ depending on the revenue source.

Release Strategies

The typical method of releasing films is with domestic theatrical, which gives value to the various film “windows” (the period that has to pass after a domestic theatrical release before a film can be released in other markets). Historically, the sequencing pattern has been to license to pay-cable program distributors, foreign theatrical, home video, television networks, foreign ancillary, and U.S. television syndication. As the rate of return varies from different windows, shifts in these sequencing strategies will occur.

The business is going through a changeover between screens that play 35mm films and those that accept digital, which makes a difference in the cost of what we usually call “prints.” Traditional 35mm prints typically cost $1,200 to $1,500 each. Using film prints, a high-profile studio film opening on as many as 3,000 to 4,000 screens in multiple markets (a “wide” release) can have an initial marketing expense of $3.5 million to $6 million, accompanied by a costly advertising program. The number of screens diminishes after opening weekend as the film’s popularity fades.

By contrast, independent films typically have a “platform” release. In this case, the film is given a build-up by opening initially in a few regional or limited local theaters to build positive movie patron awareness throughout the country. The time between a limited opening and its release in the balance of the country may be several weeks. This keeps the cost of striking 35mm prints to a minimum, in the range of over $1 million, and allows for commensurately lower advertising costs. Using this strategy, smaller-budget films can be successful at the box office with as few as two or three prints initially and more being made as the demand increases. In the new digital system, the distributor pays an $800 to $900 fee per theatrical screen on which the film is exhibited. For independent films that are in the theater for at least two months on an escalating number of screens in the platform release pattern, the overall distribution cost can still run between $1 and $2 million. As of the most recent MPAA report, there were still 2,990 non-digital movie screens in North America.

Distributors plan their release schedules not only with certain target audiences in mind but also with awareness of which theaters― specialty or multiplex―will draw that audience. Many specialty theaters remain print oriented, while multiplexes are rapidly converting to all digital. How much is spent by the distributor in total will depend on which system, and which release pattern, best serves each film.

7 / Risk Factors

Investment in the film industry is highly speculative and inherently risky. There can be no assurance of the economic success of any motion picture since the revenues derived from the production and distribution of a motion picture primarily depend on its acceptance by the public, which cannot be predicted. The commercial success of a motion picture also depends on the quality and acceptance of other competing films released into the marketplace at or near the same time, general economic factors, and other tangible and intangible factors, all of which can change and cannot be predicted with certainty.

The entertainment industry in general, and the motion picture industry in particular, are continuing to undergo significant changes, primarily due to technological developments. Although these developments have resulted in the availability of alternative and competing forms of leisure time entertainment, such technological developments have also resulted in the creation of additional revenue sources through licensing of rights to such new media and potentially could lead to future reductions in the costs of producing and distributing motion pictures. In addition, the theatrical success of a motion picture remains a crucial factor in generating revenues in other media such as DVD and Blu-ray discs and television. Due to the rapid growth of technology, shifting consumer tastes, and the popularity and availability of other forms of entertainment, it is impossible to predict the overall effect these factors will have on the potential revenue from and profitability of feature-length motion pictures.

The Company itself is in the organizational stage and is subject to all the risks incident to the creation and development of a new business, including the absence of a history of operations and minimal net worth. In order to prosper, the success of the Company’s films will depend partly upon the ability of management to produce a film of exceptional quality at a lower cost that can compete in appeal with high-budgeted films of the same genre. In order to minimize this risk, management plans to participate as much as possible throughout the process and will aim to mitigate financial risks where possible. Fulfilling this goal depends on the timing of investor financing, the ability to obtain distribution contracts with satisfactory terms, and the continued participation of the current management.

8 / THE Financial Plan

Strategy

The Company proposes to secure development and production film financing for the feature films in this business plan from equity investors, allowing it to maintain consistent control of the quality and production costs. As an independent, CCP can strike the best financial arrangements with various channels of distribution. This strategy allows for maximum flexibility in a rapidly changing marketplace, in which the availability of filmed entertainment is in constant flux.

Financial Assumptions

For the purposes of this business plan, several assumptions have been included in the financial scenarios and are noted accordingly. This discussion contains forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties as detailed in the Risk Factors section.

- Table 11.1, Summary Projected Income Statement, summarizes the income for the films to be produced. Domestic Rentals reflect the distributor’s share of the box office split with the exhibitor in the United States and Canada, assuming the film has the same distributor in both countries. Domestic Other includes home video, pay TV, basic cable, network television, television syndication, VOD, and digital streaming. Foreign Revenue includes all monies returned to distributors from all venues outside the United States and Canada.

- The film’s Budget, often known as the “production costs,” covers both “above-the-line” (producers, actors, and directors) and “below-the-line” (the rest of the crew) costs of producing a film. Marketing costs are included under Print and Advertising (P&A), often referred to as “releasing costs” or “distribution expenses.” These expenses also include the costs of making copies of the release print from the master and advertising and vary depending on the distribution plan for each title.

- Gross Income represents the projected pretax profit after distributor’s expenses have been deducted but before distributor’s fees and overhead expenses are deducted.

- Distributor’s Fees (the distributor’s share of the revenues as compared to his expenses, which represent out-of-pocket costs) are based on 35 percent of all distributor gross revenue, both domestic and foreign.

- Net Producer/Investor Income represents the projected pretax profit prior to negotiated distributions to investors.

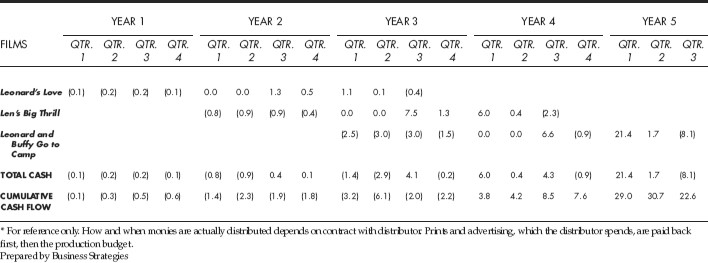

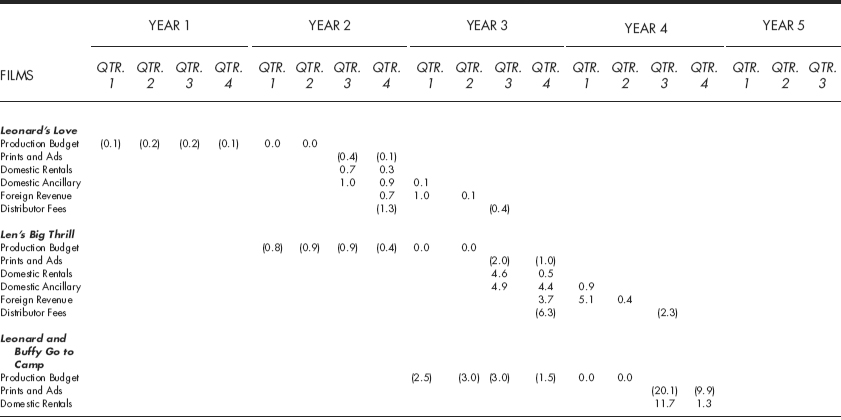

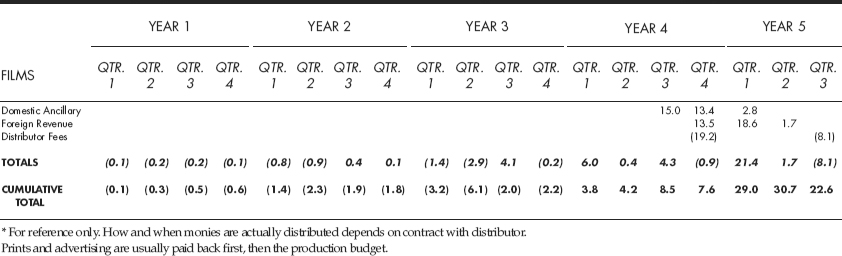

- Table 11.2 shows the Summary Projected Cash Flow Based on Moderate Profit Cases, which have been brought forward from Table 11.10.

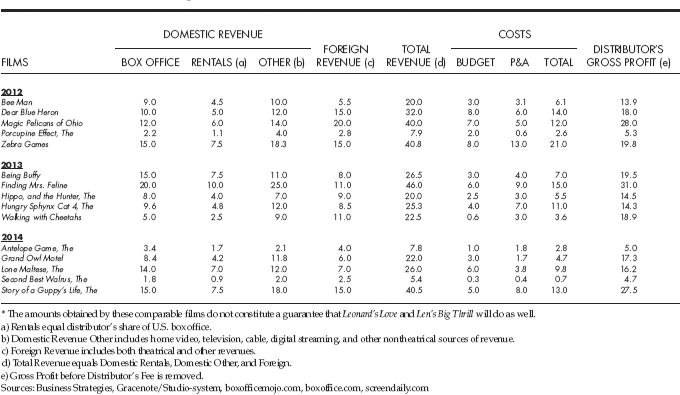

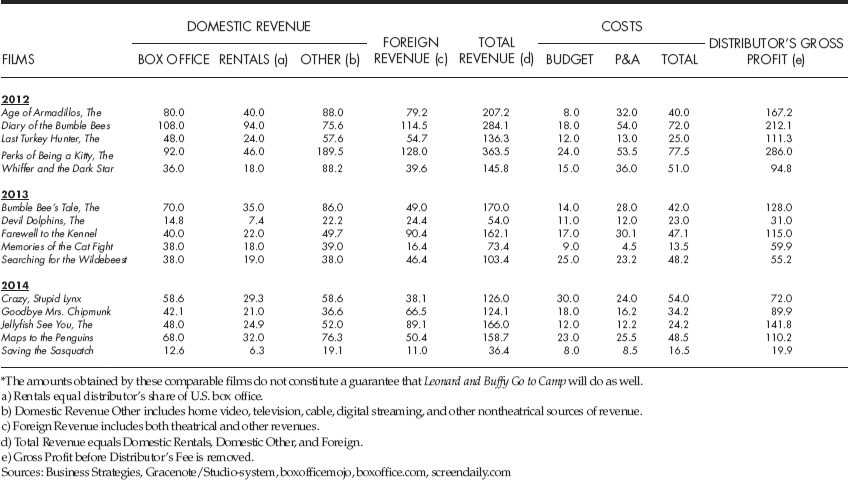

- The films in Tables 11.3 and 11.4 are the basis for the projections shown in Tables 11.7 and 11.8. Likewise, the films in Tables 11.5 and 11.6 are the basis for the projections in Table 11.9. The rationale for the projections is explained in (8) below. The films chosen relate in theme, style, feeling, or budget to the films we propose to produce. It should be noted that these groups do not include films of which the results are known but that have lost money. In addition, there are neither databases that collect all films ever made nor budgets available for all films released. There is, therefore, a built-in bias in the data. Also, the fact that these films have garnered revenue does not constitute a guarantee of the success of these films.

- The three revenue scenarios shown in Tables 11.7 and 11.8—low (breakeven), moderate, and high—are based on the data shown in Tables 11.3 and 11.4. Likewise, Table 11.9 is based on the comparative films in Tables 11.5 and 11.6. We have chosen films that relate in genre, theme, and/or budget to the films we propose to produce. The low scenario indicates a case in which some production costs are covered but there is no profit. The moderate scenario represents the most likely result for each film and is used for the cash flows. The high scenarios are based on the results of extraordinarily successful films and presented for investor information only. Due to the wide variance in the results of individual films, simple averages of actual data are not realistic. Therefore, to create the moderate forecast for Tables 11.7 through 11.9, the North American box office for each film in the respective comparative tables was divided by its budget to create a ratio that was used as a guide. The North American box office was used because it is a widely accepted film industry assumption that, in most cases, this result drives all the other revenue sources of a film. In order to avoid skewing the data, the films with the highest and lowest ratios in each year were deleted. The remaining revenues were added and then divided by the sum of the remaining budgets. This gave an average (or, more specifically, the mean variance) of the box office with the budgets. The ratios over the five years represented in the comparative tables showed whether the box office was trending up or down or remaining constant. The result was a number used to multiply times the budget of the proposed film in order to obtain a reasonable projection of the moderate box office result. In order to determine the expense value for the P&A, the P&A for each film in the comparative tables was divided by the budget. The ratios were determined in a similar fashion, taking out the high and low and arriving at a mean number. For the high forecast, the Company determined a likely extraordinary result for each film and its budget. The remaining revenues and P&A for the high forecasts were calculated using ratios similar to those applied to the moderate columns. In all the scenarios, and throughout these financials, “ancillary” revenues from product placement, merchandising, soundtrack, and other revenue opportunities are not included in projections.

- Distributor’s Fees are based on all the revenue exclusive of the exhibitor’s share of the box office (50 percent). These fees are calculated at 35 percent of the Distributor’s Total Revenue (general industry assumption) for the forecast, as the Company does not have a distribution contract at this time. Note that the fees are separate from distributor’s expenses (see “P&A” in #2), which are out-of-pocket costs and paid back in full.

- The Cash Flow assumptions used for Table 11.10 are as follows:

- Film production should take approximately one year from development through post-production, ending with the creation of a master print. The actual release date depends on finalization of distribution arrangements, which may occur either before or after the film has been completed, and is an unknown variable at this time. For purposes of the cash flow, we have assumed that distribution will start within six months after completion of the film.

- The largest portion of print and advertising (P&A) costs will be spent in the first quarter of the film’s opening.

- The majority of revenues generally will come back to the producers within two years after release of the film, although a smaller amount of ancillary revenues will take longer to occur and will be covered by the investor’s agreement for a breakdown of the timing for industry windows.

- Following is a chart indicating estimated entertainment industry distribution windows based on historical data showing specific revenue-producing segments of the marketplace:

WINDOW

MONTHS AFTER INITIAL THEATRICAL RELEASE

ESTIMATED LENGTH OF TIME

Domestic Theatrical

— 3–6 months

Video-on-Demand

3–6 months

3–6 months

Domestic Home Video (Initial)

3–5 months

6–12 months

Domestic Pay-Per-View

3–5 months

6 months

Digital Streaming

5 months

1–2 years

International Theatrical

Variable

6–12 months

International Video (Initial)

6–9 months

9–12 months

Domestic Pay Television

12–15 months

18 months

International Television (Pay or Free)

18–24 months

12–36 months

Domestic Free Television (Network, Barter, Syndication, and Cable)

3 or more years

14 years

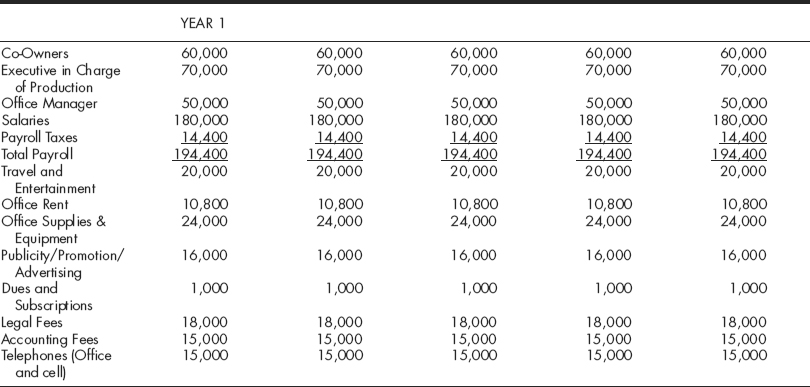

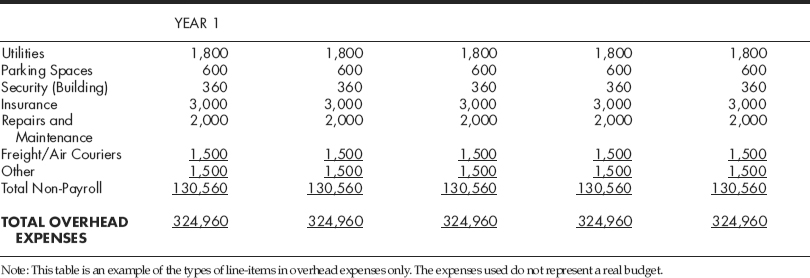

- Company Overhead Expenses are shown in Table 11.11.

|

FILMS |

BOX OFFICE |

BUDGET |

|

20 Feet from a Bear |

12.0 |

3.5 |

|

Big Birds, The |

20.0 |

9.0 |

|

Evil Reptiles 5 |

30.0 |

2.0 |

|

Hateful Spiders, The |

31.6 |

6.9 |

|

Manatee Games, The: Laughing Part 1 |

3.0 |

1.0 |

|

Other Zebra, The** |

25.0 |

7.0 |

|

Salmon In the Moonlight |

4.0 |

0.5 |

|

Theory of the Bald Eagle |

15.2 |

5.0 |

*The amounts obtained by these comparable films do not constitute a guarantee that Leonard’s Love and Len’s Big Thrill will do as well.

**Still in North American distribution as of May 23, 2016

Note: Domestic ancillary and all foreign data generally are not available until two years after a film’s initial U.S. release; therefore, this table includes U.S. domestic box office only.

Sources: Business Strategies, Gracenote/Studio-system, boxofficemojo.com, boxoffice.com. screendaily.com

|

FILMS |

BOX OFFICE |

BUDGET |

|

Beauty and the Boston Terriers |

40.0 |

8.0 |

|

Diary of a Dodo Bird |

56.0 |

20.0 |

|

Killer Mice of the North |

26.5 |

15.4 |

|

Fifty Shades of Lemurs |

60.0 |

17.0 |

|

My Big Fat Siamese 2 |

40.0 |

12.0 |

|

Praying Mantis Effect, The |

20.0 |

6.0 |

|

Secrets in the Chicken Coop |

74.0 |

23.0 |

|

Yak Outta Mongolia*** |

200.0 |

2.0 |

*The amounts obtained by these comparable films do not constitute a guarantee that Leonard and Buffy Go to Camp will do as well.

**Still in North American distribution as of May 23, 2016

***Due to its extraordinary results, Yak Outta Mongolia has not been used in the calculations for the forecast.

Note: Domestic ancillary and all foreign data generally are not available until two years after a film’s initial U.S. release; therefore, this table includes U.S. domestic box office only.

Sources: Business Strategies, Gracenote/Studio-system, boxofficemojo, boxoffice.com, screendaily.com

|

|

LOW |

MODERATE |

HIGH |

|

U.S. BOX OFFICE |

0.5 |

2.0 |

12.0 |

|

REVENUE |

|

|

|

|

Domestic Rentals (a) |

0.3 |

1.0 |

6.0 |

|

Domestic Other (b) |

0.7 |

2.0 |

13.0 |

|

Foreign (c) |

0.9 |

1.8 |

10.8 |

|

TOTAL DISTRIBUTOR GROSS REVENUE |

1.9 |

4.8 |

29.8 |

|

LESS: |

|

|

|

|

Budget Cost |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

Prints and Advertising |

0.5 |

0.5 |

3.0 |

|

TOTAL COSTS |

1.2 |

1.1 |

3.6 |

|

DISTRIBUTOR’S GROSS INCOME |

0.7 |

3.7 |

26.2 |

|

Distributor’s Fees (d) |

0.7 |

1.7 |

10.4 |

|

NET INCOME BEFORE ALLOCATION |

0.0 |

2.0 |

15.8 |

|

TO PRODUCERS/INVESTORS |

|

|

|

Note: Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals.

These projections do not constitute guarantees as how well this film will do.

a) Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals. Fifty percent of the box office goes to the exhibitor and 50 percent goes to the distributor as Domestic Rentals.

b) Domestic Other Revenue includes television, cable, video, and all other nontheatrical sources of revenue.

c) Foreign Revenue includes both theatrical and ancillary revenues.

d) Distributor’s Fee equals 35 percent of Distributor’s Gross Revenue.

Prepared by Business Strategies

|

|

LOW |

MODERATE |

HIGH |

|

U.S. BOX OFFICE |

3.0 |

10.2 |

40.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

REVENUE |

|

|

|

|

Domestic Rentals (a) |

1.5 |

5.1 |

20.0 |

|

Domestic Other (b) |

3.0 |

10.2 |

40.0 |

|

Foreign (c) |

2.4 |

9.2 |

36.0 |

|

TOTAL DISTRIBUTOR GROSS REVENUE LESS: |

6.9 |

24.5 |

96.0 |

|

Budget Cost |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

Prints and Advertising |

1.5 |

3.0 |

12.0 |

|

TOTAL COSTS |

4.5 |

6.0 |

15.0 |

|

DISTRIBUTOR’S GROSS INCOME |

2.4 |

18.5 |

81.0 |

|

Distributor’s Fees (d) |

2.4 |

8.6 |

33.6 |

|

NET INCOME BEFORE ALLOCATION |

(0.0) |

9.9 |

47.4 |

|

TO PRODUCERS/INVESTORS |

|

|

|

Note: Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals.

These projections do not constitute guarantees as how well this film will do.

a) Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals. Fifty percent of the box office goes to the exhibitor and 50 percent goes to the distributor as Domestic Rentals.

b) Domestic Other Revenue includes television, cable, video, and all other nontheatrical sources of revenue.

c) Foreign Revenue includes both theatrical and ancillary revenues.

d) Distributor’s Fee equals 35 percent of Distributor’s Gross Revenue.

Prepared by Business Strategies.

|

LOW |

MODERATE |

HIGH |

|

|

U.S. BOX OFFICE |

10.0 |

26.0 |

80.0 |

|

REVENUE |

|

|

|

|

Domestic Rentals (a) |

5.0 |

13.0 |

40.0 |

|

Domestic Other (b) |

15.0 |

31.2 |

96.0 |

|

Foreign (c) |

20.0 |

33.8 |

104.0 |

|

TOTAL DISTRIBUTOR GROSS REVENUE LESS: |

40.0 |

78.0 |

240.0 |

|

Budget Cost |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

|

Prints and Advertising |

16.0 |

30.0 |

46.0 |

|

TOTAL COSTS |

26.0 |

40.0 |

56.0 |

|

DISTRIBUTOR’S GROSS INCOME |

14.0 |

38.0 |

184.0 |

|

Distributor’s Fees (d) |

14.0 |

27.3 |

84.0 |

|

NET INCOME BEFORE ALLOCATION |

0.0 |

10.7 |

100.0 |

|

TO PRODUCERS/INVESTORS |

|

|

|

Note: Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals.

These projections do not constitute guarantee that Leonard and Buffy Go to Camp will do as well.

a) Box office revenues are for reference and not included in the totals. 50 percent of the box office goes to the exhibitor and 50 percent goes to the distributor as Domestic Rentals.

b) Domestic Other Revenue includes television, cable, DVD, and all other nontheatrical sources of revenue.

c) Foreign Revenue includes both theatrical and ancillary revenues.

d) Distributor’s Fee equals 35 percent of Distributor’s Gross Revenue.

Prepared by Business Strategies.