12

Breaking the Rules

Documentary, Animation, and, Large Format

The secret of breaking rules in a way that works is understanding what the rules are in the first place.

—MUSICIAN RICK WAKEMAN

Why Are These Films Different?

I also could have said “All Roads Lead to Rome.” A lot of people like to say variations of “rules are made to be broken.” But I feel both convey the wrong message. The important message in this chapter is not that we should throw out all the rules but we should know when they need to be slightly bent to fit the situation. Not just any road leads to Rome, but there is more than one.

The business plan outline does not change for documentary, animated, and large format (i.e. IMAX) films. You still have the same list: Executive Summary, The Company, The Film, The Industry, The Markets, Distribution, Risk Factors, and Financial Plan. However, the specifics within some of these sections vary. Each format treated in this chapter has specific areas that have to be treated differently than the “rules” laid down in the rest of the book. In addition, all the formats differ from each other in some aspects. This chapter takes you through how to treat each one and gives you examples for forecasting.

Documentary Films

History

Documentary films became mainstream 10 to 12 years ago. Until 2002, I didn’t write any business plans for theatrical documentaries. The reason is simple: There weren’t enough of them that had earned significant revenues worth talking about. The majority of feature-length docs were made for television. The success of Roger & Me in 1989 began the re-emergence of the nonfiction film as a credible theatrical release. Then throughout the 1990s and continuing to present day, theatrical docs have continued to grow in prominence and popularity with audiences.

After a few successful films in the early 1990s, Hoop Dreams (1994) attracted a lot of attention by reaching U.S. box office receipts of $7.8 million on a budget of $800,000. The same year, Crumb reached a total of $3 million on a budget of $300,000. In 1997, a Best Documentary Oscar nominee, Buena Vista Social Club, made for $1.5 million and grossing $6.9 million, scored at the box office and with a best-selling soundtrack album.

Michael Moore’s 2002 Bowling for Columbine raised the bar for documentaries by winning the Oscar for Best Feature Documentary and the Special 55th Anniversary Award at Cannes and by earning $114.5 million worldwide. The same year, Dogtown and the Z-Boys, The Kid Stays in the Picture, I’m Trying to Break Your Heart, and Standing in the Shadows of Motown all made a splash at the box office. The success of these releases was not anything like Columbine, which had a political and social message, but it was noticeable nevertheless. In 2003, Spellbound seemed to confound the forecasters by drawing a significant audience, as did Step into Liquid, The Fog of War, and My Architect. The following year, 2004, Michael Moore surprisingly and convincingly—bettered his own record with Fahrenheit 9/11, which was made for $6 million and earned more than $300 million worldwide. Distributors found more documentaries that they liked: Riding Giants, The Corporation, Touching the Void, and the little doc that could, Super Size Me (made for almost nothing and earning $35.2 million at the box office). In 2005, there were the popular Mad Hot Ballroom, March of the Penguins, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, and Why We Fight. In 2006, another breakout in terms of monetary success was An Inconvenient Truth (made for a reported $1.5 million and earning $75.3 million worldwide). Featuring a fledging actor, former Vice President Al Gore, undoubtedly added to the film’s popularity. The same year was Kirby Dick’s This Film Is Not Yet Rated about the secretive decision making of the MPAA’s ratings board. Speaking at Sundance the following year about having more inclusive descriptions of the ratings, Chairman Dan Glickman acknowledged that Dick’s film had made an impression on himself and others.

In 2007, the critics said that documentaries were “dead,” as Michael Moore’s Sicko was the most significant entry in the genre. To paraphrase yet another Mark Twain quote, the reports of the box office death for theatrical docs was greatly exaggerated. In 2008, another genre broke through the barrier with Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed with perhaps the opposite end of that social discussion shored up by Religulous. We also saw the biographical film become a major force from 2008 to 2015 with Amy earning $8.4 million in 2015. Other significant docs in the last two decades have been Exit Through the Gift Shop, Inside Job, Searching for Sugar Man, Bully, and 20 Feet from Stardom.

Synopses

In Chapter 3, “The Film,” I make a big deal about telling the investors how the story ends. If you don’t know the entire storyline and ending of the film, you probably should wait to raise money. Investors aren’t looking for surprises with narrative films.

A favorite quote of mine is: “In feature films the director is God; in documentary films God is the director,” Director Alfred Hitchcock.

With all documentaries you are making a film about a real subject. Nevertheless, there are still two general types of storylines: historical time and future time. Historical documentaries have an ending before you start making the film. The term historical is less a reference to time than that you and the investors know the ending of the story. With future time, or what I usually refer to as real-time documentaries, you are recording actual events as they happen. For example, you are curious how the latest miracle drug was discovered, tested, and won approval from the Federal Drug Administration. You are doing historical research. For your investors, there is a clear storyline outline plus an ending to the story. You still may discover facts along the way that weren’t known before, but your synopsis will look a lot like that for a fiction film.

In a real-time documentary, you may be following new non-drug interventions in several states for a specific health issue. You won’t know until after the study is over. While I insist on the “whole storyline including the ending” with fiction films, it is not possible to know in advance how this story will end. The synopsis will include a description of why you are making the film, what the study will include, and perhaps what you anticipate the results will be. An example for the last lines of the synopsis might be:

The entire process will be captured on film. This visual record of the transformations in the test subjects will prove _____. The results of this experiment in __________ may directly and indirectly affect the over 100 million people living with supposedly incurable ____________.

Interviews

Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.

―MARK TWAIN

Many documentaries are based on a large number of interviews. If you have already conducted some of the interviews, then list those people with their credentials. If you haven’t already conducted the interviews, be careful how you mention people. I treat the contemplated list of interviews the same way as I treat listing stars in a film. You may want to talk to include an interview with Boston Patriots Quarterback Tom Brady in your film. If you already have an affirmative response from him, include his name in your list of interviewees. Otherwise, “people we would like to interview” is really the same as naming stars who have never heard of you. The interviews give credibility to your potential film for the investor. Whether equity or grant money, it is not a good idea to get funded by making promises you can’t keep.

The bios for these interviews are listed as Attachments to the synopsis in the same way you would list actors. However, in the making of many documentaries, there are advisors who may help with structuring the film but not be part of it. These people I always list in the “Company” section under Advisors (different from consultants such as me and the attorney), with one line stating their current or most recent special credential. An example of such a listing is: Buffy Celery, Head of Agricultural Production and Foods Quality for QTR, Inc.

Markets

The target markets for documentaries are the same as those for fiction films, save one group. Documentary audiences themselves are the first target audience to list. For example, the paragraph I used in a recent documentary reads:

Documentary films have entered the mainstream. Throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century, documentary films have gained prominence and success on the theatrical screen. Part of the reason is the quality and diversity of the films. Documentaries ranging from the political and Inside Job to bios like Amy and the music-centered Searching for Sugar Man are among nonfiction films that have earned substantial sums at the box office. Audiences eager to see intellectually stimulating, well-crafted fare are being drawn to theaters showing documentaries, resulting in attendance figures that have increased the value of these films in the home video, cable, and foreign markets. In addition, a substantial portion of the television audience for documentaries—estimated by Nielsen Media Research at 85 percent of U.S. television households—appears unwilling to wait 6 to 12 months for a documentary to get to cable and longer for network television. Analysts also suggest that audiences’ interest in reality television has helped documentary films build their growing theatrical audience. In addition, sales agents have said that documentaries that are more cinematic, with song scores and the evolution of characters, can be pitched more easily and sold in much the same way as dramatic features.

The rest of the market section is the same as that for fiction films. Every documentary has a subject, be it political, economic, inspirational, historic, sports related, and so on. Fiction films with the same genres or themes can be used as examples in the market section as well as to show interest in the subject, although they can’t be used as comparatives for forecasting.

The discussion of audience ages depends on the subject of the documentary. The main market may be an audience over 30 if the film is political, although cable and social media have made that subject more interesting for older teens and the college-age audience. Musical, sports, and other docs depend on who or what is being featured. For example, a film about skateboarders might draw in a younger audience, and one featuring a baseball, football, or basketball star from the 1950s or 1960s would draw in baby boomers first.

Forecasting

In the previous two chapters, I made a big point that you need the worldwide numbers over the most recent three years available with 14 to 15 films to do my method of forecasting. Unfortunately, documentaries, as well as animated and large format films, are not available in large enough numbers every year to follow that rule. Due to the limited number of films and the lack of some information, you will probably have to go back more than five years to have at least ten films to compare. There is more responsibility placed on you, the filmmaker, to be sensible and logical throughout the process. I know that many of you would rather never think about numbers. However, your investors do. Your forecast must look rational to them. Films from 1994 are not appropriate as comps in 2016.

Which documentaries to use and which not to use is a choice you will have to make. There is more flexibility in terms of genres and themes for what films you can use, but your decision-making process has to be reasonable. The first step is to look at everything in your story. If you are making a film involving political/economic/social subject, there are a lot of choices. These subjects tend to be what many filmmakers want to explore, especially in difficult times. They reach a broader audience, particularly with all the turmoil that has been going on around the world. I can’t give you a hard-and-fast rule for which documentaries to use; it has to be your choice. One of my favorite docs for which to do the financials was Jonathan Holiff’s My Father and the Man in Black. His father was Johnny Cash’s personal manager. In addition to being about a father/son relationship, the themes in the story are varied. A short review read: “From hillbilly juke joints in the Deep South to the grandeur of London’s Royal Albert Hall, from ditches and jail cells all the way to the White House.” This gave me a lot of latitude in choices.

Budgets

There also were films that I wanted to use based on their box office results; they were not in the database due to lack of data. Or I might not have a good reference for a doc’s budget until the database provides the worldwide numbers.

Reason number one given by many documentary filmmakers is that they have made the film over a long period of time and didn’t keep records of how much money was involved. It is true that many are made with a combination of cash from grantors and in-kind contributions, but a filmmaker has to keep careful financial records. Or, reason number two, they choose not to tell us, which happens far more often than with other feature films. Therein is the biggest problem with writing a business plan around a documentary film. It has gotten somewhat better in recent years; however, in my weekly database of release indie films, it is more likely that I won’t have a budget for a doc. If you are raising money from other people—whether individuals or grant organizations—you must know the budget. Even if you are using your own money, please figure out your budget ahead of time. When I first came into the business, documentary filmmakers often raised money as they went along. Those times are gone. Documentary filmmakers are expected to be professional.

The range of applicable films to use normally is very narrow with theatrical documentaries. The majority of docs that appear profitable have budgets between $150,000 and $2 million. I always counsel clients to plan on making their film for $2 million or less. Even with a moderate box office, there are many sources for revenue. Specialized films often benefit from additional marketing that is not in the normal plan for film distribution companies. In addition to the traditional distribution channels of which Netflix and other commercial sites are now part, there tend to be more alternative and advocacy groups, both nationally and internationally, though which documentarians can sell their film.

Table Layouts

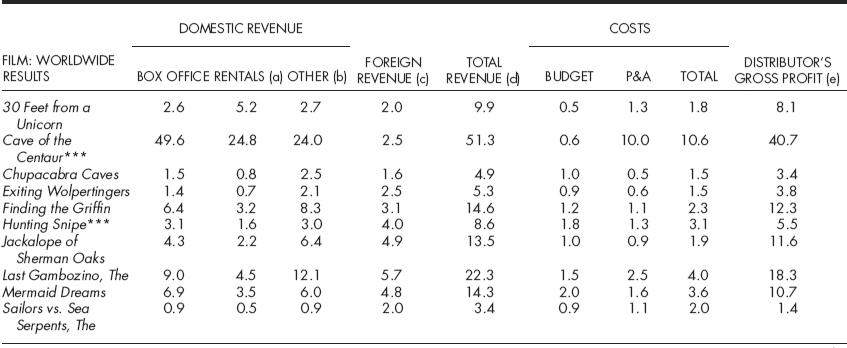

As mentioned earlier, with items, such as budget and ancillary, harder to obtain, I may go back ten years to have at least ten films. Therefore, instead of breaking the films into three years to have a trend in the ratios, I keep them in a single list as in Table 12.1. For most documentary business plans, I have both films with worldwide numbers and those with only current domestic box office and budget on the same table. In most two-year periods, there have not been enough documentaries. If there are four or more in the two most current years, then I will have a second table similar to the one for narrative films. As with other films, the box office has to give the impression that the films will be profitable. If the budget is $3 million and the final box office is $42,000, you don’t need to include the film. Investors will know that film will not be profitable.

As when making a table of other feature films, list the extraordinary films when they are appropriate (i.e. Cave of the Centaur Table 12.1), but do not include them in your forecasting process. Even though it is tempting to use their high revenues, remember that your investor probably will know better. You want him to have confidence in you.

Note that fiction films are not included into a forecast for a documentary. They have a wider audience appeal and usually wider distribution. All of the revenue windows for a fiction feature are going to show higher grosses. Using them would mean that you are fooling not only yourself with an unlikely net profit number but also your investor.

On the other hand, a successful documentary in the same budget range as your feature film with good results can be used in that plan. For example, Inside Job can fit in a low-budget film plan that deals with financial crisis, crime, and politics, themes that have become more prevalent in recent years. As we always are looking at a conservative revenue projection for our “Moderate” column, using a film that has done well with a lower net profit result is not a problem.

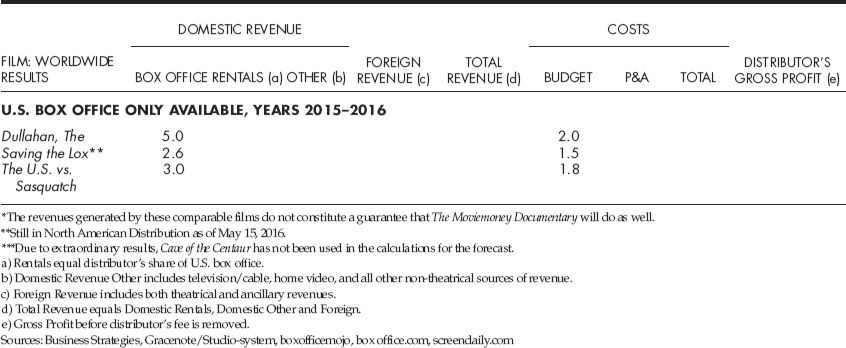

Finishing

Once you have set up your comparative table, you are ready to follow the forecasting method outlined in Chapter 10 and in the “Financial Worksheet Instructions” in the book’s companion website. The only difference will be one average ratio to use for forecasting your revenue. Otherwise, forecast your revenues and expenses and create your cash flow with the same methodology used for narrative films.

Animated Films

Independents

It is likely you have a budget that is far lower than that of the studios—probably between $5 million and $50 million. If you are trying to raise $150 or $200 million independently for your first animated film, I would suggest rethinking your plan. You can write the business plan, but be realistic about where you are going to find the money. As with documentaries, much of the business plan for an animated film is the same as other feature films. There are specific areas that differ, however.

Industry

The changes in technology affect the making of animated films to a greater extent than other movies. Although 2D still exists, 3D is involved in a majority of films. In addition, the techniques have changed. I usually put in a short animation section as either a part of the Industry section or a separate section directly following it. In either case, it should have its own heading. Below is a sample of what might be in the business plan. You would want to expand on whatever format you are using. If your film is to be in 3D, for example, then follow the animation paragraph with an explanation of 3D and examples:

Animation is the rapid display of a sequence of images of 2D or 3D artwork or positioned model(s). The effect is an optical illusion of motion due to the phenomenon of “persistence of vision,” which can be created in several different ways. While some forms of animation can be traced to ancient times, narrative animation did not really develop much until the advent of cinematography. One of the first people to use animation in film was the Frenchman George Melies, the silent film director featured in the live-action film Hugo. J. Stuart Blackton made the first American animated film, a short, in 1906. The Walt Disney Company made the first feature-length U.S. animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, in 1937. While many of the full-length animated films through the years have been made by studios, advances in technical methods and the ability to lower costs have brought independent companies into the animation business. The Weinstein Company, Lucasfilm, Aardman Animations, and Imagi Animation Studios are just a few of the independents making animated films today.

Note that I did not include DreamWorks Animation which was sold to Comcast Communications in April 2016 making it part of Universal Filmed Entertainment Group, which includes Universal Pictures.

Markets

As with other genres of film, the audience is specific and knows what it likes. Techniques and storylines are discussed in other sections of the business plan. The demographics make a big difference with how you pitch animated films to investors.

Moviegoers of All Ages

Assuming that you “thinks market” before starting a film, there are two ways of designing an animated film. Either it is made for children who adults might accompany, or it is designed for teens and older. The theory is that DreamWorks Animation’s formula is to make films primarily for adults that may be entertaining for younger moviegoers as well; for example, Paddington films play to everyone from 8 to 80. Certainly, older audiences still feel that these films play better on a big screen and want to see it in the theater initially.

Many of the films are designed to appeal to everyone from children to their grandparents. Due to the paucity of G-rated live-action films, animation is often not in competition for the same audience as live-action films that are released concurrently. They can play to younger ages better than many other films, while still bringing in the whole family demographic. Parents often go to check out a film before taking a very young child. Grandparents go to enjoy the activity with the rest of the family.

The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) reports the attendance levels of moviegoers from 2 to 60+ in specific groups in their “Theatrical Market Statistics.” There is a big difference between a film fit for a four-year-old and one for a preteen. For example, one animated film may be aimed primarily at children aged eight and under. Another animated film, with a slightly more hip theme and a pop music soundtrack, may entertain children but also draw in teenagers and young adults. The Weinstein Company’s The Nut Job was geared for the very young to the very old, while Laika’s The Boxtrolls skewed to teenage viewers.

A part of the definition for a G-rating reads: “nothing in theme, language, nudity, sex, violence or other matters that, in the view of the Rating Board, would offend parents whose younger children view the motion picture.” Despite the rating (which the MPAA makes clear is not a certificate but an opinion of a panel), some adults may feel that there may be activity in the film that is not appropriate for little Sally. Looking at the top ten animated films released in the United States from January 2014 only one—Rio 2—was rated G, and it was a Twentieth-Century Fox film. All others were PG. If you feel that you want to make an independent film for young children and don’t have any, talk to parents for their viewpoint.

Besides being a valued family outing, parents are teaching their children to appreciate movies on the large cinema screen. The good news about those very young children is that they are a boon to home video companies. Their parents tend to buy discs that they can play over and over again on child-level technology.

Financials

Budgets

As with documentaries, you will need to go back more than five years to have enough films for a proper forecast. How far back depends on what is available in terms of budget. The business plans for animated films that I am doing in 2016 generally have worldwide data from 2008 to 2014. While 12 films is a better statistical sample for making a forecast, I often have to settle for 10.

There are a number of animated films every year. The majority are in the $120 to $200 million-plus range. As much as you might think your $5-, $10-, or $20-million film compares, it doesn’t. Nevertheless, the range of budgets for comparative films is much wider. In the early years of this decade, there were a number of successful animated films that were made for less than $10 million. Unfortunately, in the last few years, there have been very few. With a lower-budget film, you may have to go as high as $40 million when seeking titles for comparison. Even for a film budgeted at $40 million, I don’t go above $90 million in choosing comparatives. I also stay in this century. There have been too many technical improvements over the years to use films from an earlier period.

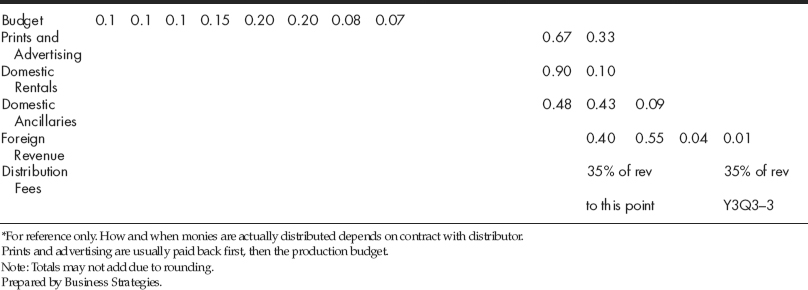

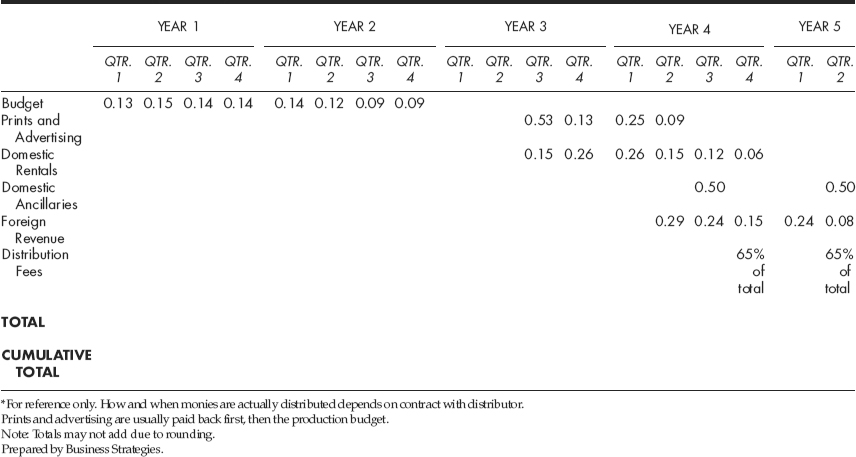

Table Layouts

The Table 12.2 format should be used for animated films to show the worldwide revenues and expenses through the most current year available; however, there will be enough films from the most recent two years to create a second table similar to the layouts described in Chapter 10. The forecasting for an animated film also follows the methodology in Chapter 10. Animated films do differ in creating the cash flow table. Experienced filmmakers of animation with whom I have worked always have assumed two years for the production cost rather than one year. I recommend that you do the same. Otherwise, use the same percentages for calculating the spread for the prints and ads cost, domestic and foreign revenues, and distributor fees.

Large-Format Films

History

Large-format films are made by several companies, among which are the IMAX Corporation, studios, and independent producers. They are commonly referred as IMAX films, since the industry started at EXPO ’70 in Osaka, Japan, when IMAX Corporation of Canada introduced “the IMAX; Experience” at the Fuji Pavilion. These days, however, IMAX produces fewer of the films, but an overwhelming percentage of the “giant” screens. Warner Bros. is another studio producer, and there are independent producers discussed later in this chapter. Based on information from the IMAX Corp. there were 1,066 IMAX theatres―952 commercial multiplexes, 17 commercial destinations, and 97 institutions―in 68 countries.

Until 1997, these theaters were located in museums, science centers, and other educational institutions, as well as a few zoos. In 1997, IMAX introduced a smaller, less-expensive projection system that was the catalyst for commercial 35-mm theater owners and operators to integrate their theaters into multiplexes. Currently, these films are 40 to 50 minutes long.

The first independent producers of these films were Greg MacGillivray and the late Jim Freeman. They began with surfing films in 1973. The cameras they used weighed 80 pounds, but they paid IMAX to make a camera with better specifications. Since that time, the MacGillivray Freeman Company has led the independent way with 20 productions. Among the other independent producers are nWave Pictures, 3D Entertainment, National Geographic Cinema Venture, and 3ality Technica.

Formats

In 2002, IMAX introduced a process to convert 35-mm film to 15/70 (15 perforations/70-mm process), which is their standard. Known as DMR, for “digital remastering,” the process started a new wave of converting longer feature films to be shown on the larger screens. There is ongoing controversy about whether fiction features belong to a giant screen. However, that is for you to decide. Suffice it to say that the economies of scale are different.

Another controversy erupted when IMAX introduced a new digital screen to multiplex theaters in 2009. Since 2004, the size of the IMAX screens has been 76 × 98 feet (23 × 30 m), while the new screens are 28 × 58 feet (8.5 × 18 m). The newer systems cost $1.5 million to get up and running compared to $5 million for an “original” IMAX. The company’s multiplex agreements allow the removal of the lower portion of seating in stadium-seat venues, creating the perception of greater screen size and viewing immersion. Presumably, the remastering of 35-mm films boosts image resolution and brightness. Then there is the question if you can call them “giant screens.” An IMAX representative insists that, “It isn’t about a particular width and height of the screen. It’s about the geometry.” In the end, the audience will decide. They won’t care about how much it cost to make the film, equip the theater, or remaster the film. They will care how it looks to them, and whether they should have been charged $5 more for a film that isn’t on a six-story screen.

Synopses

Films produced as large-format films, as compared to the remastered films, have always been documentaries, and this rule still applies. Therefore, the synopsis for a film is essentially like those discussed in the “Documentary” analysis earlier. They are in both historical and future time. In putting together a business plan, list advisors in the company section and people appear in the film as attachments after the synopsis.

Markets

As with other documentaries, I use the IMAX audience as the first target market to discuss. Then use other genres and themes in the films. The demographics are going to relate to the stories in the films.

Financials

That brings us to the bottom line for these films. Sources of data are few. The only films we can use for forecasting are those that appear in commercial theatrical venues. There are no numbers for films in museums.

The previously mentioned independent companies tend to finance films from the profits of their own films. Independent filmmakers generally have been funding films as they would other documentaries—with grants, corporate donations, and funds from specific groups that may have a social or business interest in the subject of the film. Obtaining financing from equity investors appears to be rare for individual filmmakers; nevertheless, we need to have a format for approaching them.

Expenses

The problem comes on the cost side—not only the budgets but also how distributors of giant-screen films calculate their fees. Since we can use only films for forecasting for which the budgets are known, there always will be films that cannot be used as comparatives. Both the budgets and the prints and ad costs are included on the Baseline website.

There is a difference in the split, however. In addition, in over 12 years of covering this part of the film industry, I have never found a written analysis of the split between the distributor and the producer. This lack of financial knowledge also makes it difficult to approach equity investors with a business plan. Anecdotally, various filmmakers and distributors have told me that the split is the opposite of what we would assume for an independent film—65 percent to the distributor and 35 percent to the producer. There is further difficulty concerning the search for accurate figures. After interviewing filmmakers and distributors at the annual conference of the Giant Screen Theater Association and, prior to that group, at the Large Format Cinema Association (in 2006, the LFCA merged with the Giant Screen Cinema Association to form GSTA), I have learned that the ongoing independent producers, MacGillivray Freeman, nWave, and others, have made profits from earlier films and, in some cases, distribute their own films. The best we can do at this time is to use this information, along with additional information that we get from Baseline to present a business plan.

Table Layouts

The tables for comparative films are set up similarly to the ones for animated films. Large-format films also are released in varying numbers over the years. To have 10 or 12 films to use as comparatives, you are likely to have to start with a year seven to nine before the current year. For example, in 2016, I might have a range of 2008 to 2016. The forecast is also set up the same way as the other tables. The difference is that the distributor’s fee is 65 percent of the total revenue.

An individual large-format film can appear on screens off and on for several years. Table 12.3 shows the cash flow spread for a large-format film. The production cost in this example is the same spread as an animated film. Whether live-action or animated film, the time consumed is likely to be similar.

The domestic revenues are based on the study of independent films released from 2006 to 2016. The data show an average of 93 percent of the domestic revenue coming in over the first year (four quarters) after distribution start. While revenue can keep trickling in for several years as films move from theater to theater, much of the later revenue is in small amounts and relatively inconsequential to the total profit percentage relative to the budget.