The best short definition of news is ‘that which is new, interesting and true’. ‘New’ in that it is an account of events that the listener has not heard before – or an update of a story previously broadcast. ‘Interesting’ in the sense of the material being relevant, or directly affecting the audience in some way. ‘True’, because the story as told is factually correct.

It is a useful definition not only because it is a reminder of three crucial aspects of a credible news service but because it leads to a consideration of its own omissions. If all news is to be really ‘new’ a story will be broadcast only once. Yet there is an obvious obligation to ensure that it is received by the widest possible audience. At what stage then can the news producer update a story, assuming that the listener already has the basic information? What do we mean by ‘interesting’ when we speak not of an individual but of a large, diversified group with a whole range of interests? Do we simply mean ‘important’? In any case, how does the broadcaster balance the short-term interest with the long? And as for the whole truth – there simply is not time. So how should we decide, out of all the important and interesting events which confront us, what to leave out? And concerning what is included, how much of the context should be given in order to give an event its proper perspective? And to what extent is it possible to do this without indicating a particular point of view? And if the broadcaster is to remain impartial, do we mean under all conditions? These are some of the questions involved in the editorial judgement of news. Let’s first admit that ‘interesting’ is by no means the same as ‘important’.

What is it that actually interests our fellow men and women? We noted that it was anything being relevant or directly affecting people – relating to them – or which might do.

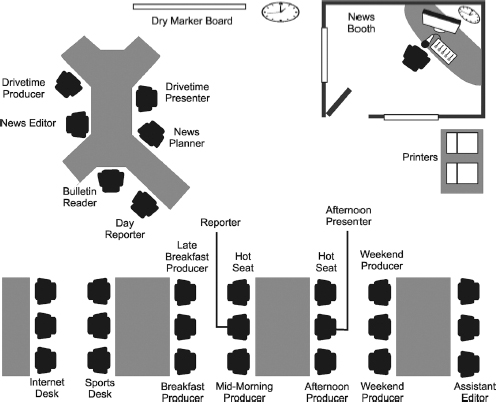

Figure 7.1 Part of the main BBC newsroom at Broadcasting House, London. It is the largest newsroom in the world, supported by some 3,000 journalists. It provides 24-hour news for all the BBC’s national and regional television and radio services, 41 local radio stations, World Service radio and television – and 27 language services, together with hundreds of thousands of Internet web pages. It is linked to a network of BBC correspondents around the world

Broad areas of interest are:

• conflict: wars, strikes, political argument, business take-overs, success and failure;

• disaster: tragedy, plane/train crashes, missing persons, epidemic illness, refugees, cyclone;

• development: building plans, new discovery, exploration, job creation, medical advance;

• crime: murder, corruption, theft, violence, fraud, drugs, trafficking, child abuse;

• money: lottery wins, the budget, stock market gains or losses, buried treasure, price increases;

• sex: how people behave, marriage and divorce, rape, paedophilia, research findings;

• famous people: celebrity lifestyle, achievement and awards, scandal, obituary;

• sport: league winners and losers, results (betting), records set – ‘firsts’, who is ‘best’?

Just take one example – a cyclone that blew itself out over the Pacific wouldn’t be all that interesting, but one that devastated the Philippines with huge loss of life was (see pp. 255–6). Quantity makes a story significant – how many people were killed? How much money was lost? By how much was the new record better? How long was the prison sentence?

Distance also affects our judgement – a mining disaster in China’s Bei Shan Province is unlikely to have the same impact as a smaller one within our own borders.

We will come back to the detail of news values, but a key question is always – how will this affect my listeners’ lives?

Starting with the consumer, what does the news listener expect to hear? Certainly in a true democracy the public has a general right to know and discuss what is going on. Most people will find that interesting. However, there will be limitations, defined and maintained by law – matters of national security, confidences of a business or private nature, to which the public does not have rightful access. But these reasons can be used to cloak the genuine interest of the individual. Caught in such a conflict, the broadcaster is faced with a moral problem – the not-unfamiliar one of deciding the greater good between upholding the law and championing the rights and freedom of the individual. At such times, those involved in public responsibility should consider three separate propositions:

1 Broadcasters are not elected: they are not the government and as such are not in a position to take decisions affecting the interest of the State. If they go against the practice of the law they do so as private citizens, with no special privileges because they have access to a radio station.

2 Associated with the public right to know is the private right not to divulge. A society that professes individual freedom does not compel or allow the media to extract that which a person wishes lawfully to keep to himself.

3 What harm or discomfort may the journalist be causing by reporting – or not reporting – events? It’s important to show good taste and avoid pandering to salacious curiosity.

Thus the listener has a right to be informed; but although the constraints may be few and the breaches of it comparatively rare, the right is not total. Broadcasters must know where they stand and on what basis the lines of editorial demarcation are drawn. Journalists in particular will remember that they are accountable to the listener. That is the purpose of having a by-line or credit attached to their work.

We have already seen that newsrooms often have their own stringent ethical standards. These are often given the force of law – in Britain, the Broadcasting Acts of 1990 and 1996, updated by the Communications Act of 2003 establishing Ofcom as the regulatory body to issue and uphold the professional Codes of Practice. The BBC has its own guidelines (see p. 386). These have to be fully understood and implemented by any working journalist. Some are self-evident – the need to be fair in political reporting, with particular constraints applying to election coverage, the care taken not to misrepresent an interviewee, the correction of factual errors, the dangers of simulated newscasts, interviewing people wanted by the police, any abusive treatment of the beliefs of adherents of any religion, and so on.

But others need special vigilance, such as the reporting of terrorism. The UK’s Terrorism Act 2000 sets out to ensure that reports of terrorism do not amount to incitement. It broadly defines terrorism as ‘the use or threat of action where the threat is designed to influence the government or intimidate the public . . . for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, or ideological cause’. Interviewing people who advocate violence therefore needs special care. It becomes a criminal offence to invite support for any proscribed organisation. Again, violence must not be described for its own sake and it must not be ‘glorified or applauded’. The Official Secrets Acts also constitute an area requiring special expertise.

In the case of the BBC, the basis of news and current affairs broadcasting has always been – and still is – first, to separate for the listener the reporting of events (news) from the discussion of issues and comment (current affairs), and second, to give both, or more likely all, sides of an argument. This is best achieved from the position of being informed but independent. Of course there are journalists who see broadcasting as a means of indulging their own attempts at public manipulation, just as there are governments that see news purely in terms of propaganda for their own cause. But to quote the DFID booklet Media in Governance:

If the media are puppets of government, they will soon lose credibility with the public. Without credibility, government manipulation of the media may fool politicians but will not ultimately fool the people. Even true messages may be disbelieved.

People sheltered from unpalatable truths cannot decide, and cannot grow. Arising from the broadcaster’s privileged position as the custodian of this form of public debate, the role of a radio service, even one under government or commercial control, is to allow expression to the various components of controversy but not to engage itself in the argument nor to lend its support to a particular view, i.e. to be impartial. However, such a policy is by no means universal and stations in some countries are encouraged to take an editorial line. In Britain, radio was for many years the monopoly of the BBC, and as the only provider it had to be as objective as possible. Where there are several broadcasting sources, each may develop its own attitude to political and other controversial issues and, like a newspaper, attempt to sway public opinion.

Where news is written by a government office, there is always the emphasis on supporting its own achievements – ‘The government has performed another miracle today . . . ’. However, objectivity requires a news channel always to distance itself, even slightly, from its sources. This is better as: ‘The government says it has performed another miracle today . . . ’. The difficulty stems from the fact that many governments of new nations see their essential task as nation building, so they believe they have to say how good everything is. Their broadcasting is not about challenging the mediocre or wrong, so you can’t publish anything detrimental if you want to keep your job. Nevertheless, ways should be found of expressing truth so that broadcasting is fully credible.

What is the meaning of impartiality when covering a complex industrial dispute involving official and unofficial representatives, breakaway groups, vocally militant individuals and separate employers’ and government views and solutions?

Even more difficult situations were those such as Northern Ireland or post-war Iraq where there has been a ‘limited’ civil war. Do we give equal time for those who would uproot society – for those who oppose the rule of law? These are not easy questions since there is a limit to the extent to which anyone may be impartial. When one’s own country is involved in armed conflict it is extremely difficult, perhaps not even desirable, to be neutral – but one must, as far as possible, remain truthful. While society may be divided and changing in its regard for what is right and wrong, it is less so in its more fundamental approach to good and evil. No public medium of communication can function properly and without critical dissent unless society is agreed within itself on what is lawful and unlawful. It is possible to be impartial in a peaceful discussion on attempts to bring about changes in the existing law, but such impartiality is not possible in reporting attempts to overthrow it by force. One can be objective in reporting the activities of the man with the gun, but not in deciding whether to propagate his views.

A former Director General of the BBC, Sir Hugh Greene, said:

I do not mean to imply that a broadcasting system should be neutral in clear issues of right and wrong, even though it should be between Right and Left. I should not for a moment admit that a man who wanted to speak in favour of racial intolerance has the same rights as a man who wanted to condemn it. There are some questions on which one should not be impartial.

There are those who disagree that race relations is a proper area for showing partiality, just as there are those who oppose the underlying acceptance of the Christian faith as a basis for conducting public affairs. This is not an abstract or purely academic issue, it is one that constantly faces the individual producer. Decisions must be made as to whether it is in the public interest to give voice to those who would challenge the very system of democracy which enables that freedom of expression. On the one hand, to give them a wider currency – ‘the oxygen of publicity’ – may be interpreted as a form of public endorsement, on the other, to expose them for what they are could result in their total censure. What is important is the maintenance of the freedom to exercise that choice, and ultimately to be accountable for it to an elected authority. Sir Geoffrey Cox, former Chief Executive of ITN (Independent Television News), has said of the broadcaster’s function:

It is not his duty, or his right, to editorialise on the question of democracy, to advocate its virtues or attack its detractors. But he has a firm duty to see that society is not endangered either because it is inadequately informed, or because the crucial issues of the day have not been so probed and debated as to establish their truth. A good broadcast news service is essential to the functioning of democracy. It is as necessary to the political health of society as a good water supply is to its physical health.

To stay within the law demands a knowledge of the legal process and of the constraints that the law imposes on anyone, individual or radio station, to say what they like. In Britain no one, for example, is allowed to pre-judge a case that is to come before a court, to interfere with a trial, influence a jury or anticipate the findings. Thus there are considerable restrictions on what can be reported while a matter is sub-judice. To exceed the defined limits is to run the very severe risk of being held in contempt of court – an offence that is viewed with the utmost seriousness, since it may threaten the law’s own credibility.

Under present British law the outline of what is permissible in reporting a crime falls under four distinct stages:

1 Before an arrest is made it is permissible to give the facts of a crime but the description of a death as ‘murder’ should only be used if the police have made a statement to that effect. Witnesses to the crime can be interviewed but they should not attempt to describe the identity of anyone they saw or speculate on the motive.

2 After an arrest is made, or if a warrant for arrest is issued, the case is said to be ‘active’. This continues while the trial is in progress and it is not permissible to report on committal proceedings in a magistrate’s court, other than by giving the names and addresses of the parties involved, the names of counsel and solicitors, the offence with which the defendant is charged, and the decision of the court. The reporting of subsequent proceedings in the higher court is permitted but no comment is allowed. The matter ceases to be ‘active’ on sentence or acquittal.

3 Responsible comment is permissible after the conviction and sentence are announced, so long as the judge is not criticised for the severity or otherwise of the sentence, and there is no allegation of bias or prejudice.

4 If an appeal is lodged, the matter again becomes sub-judice. No comment or speculation is allowed and only factual court reports should be broadcast.

Complications can arise if the police are too enthusiastic in saying that ‘they have caught the person responsible’. This is for the court to decide and broadcasters should not collude with police in pre-judging a case. There are special rules that apply to the reporting of the juvenile and matrimonial courts. The key question throughout is whether what is broadcast is likely to help or hinder the police in their investigation or undermine the authority of the judicial process.

Such matters are the stock in trade of the journalist, and producers unacquainted with the courts are advised to proceed carefully and to seek expert advice.

The second great area of the law of which all programme makers must be aware is that of libel. The broadcaster enjoys no special rights over the individual and is not entitled to say anything that would ‘expose a person to hatred, ridicule or contempt, cause him/her to be shunned or avoided, lowered in the estimation of society, or tend to injure him/her in their office, profession or trade’. To be upheld, a libel can only be committed against a clearly identifiable individual or group. In civil law, it is not possible to defame the dead. The most damaging accusation that can be brought against a broadcaster standing under the threat of a libel action is that he or she acted out of malice. This is not an unknown hazard for the investigative journalist working, for example, on a story about the possibility of corruption or dubious practice involving well-known public figures. The broadcaster’s complete real defence against a charge of libel is that what was broadcast, i.e. published, was true, and that this can be proved to the satisfaction of a trial judge, and in some cases perhaps a jury as well. Again, we have the absolute necessity of checking the facts and using words with a precision that precludes a possibly deliberate misconstruction.

A second defence is that of ‘fair comment’. This means that the views expressed were honestly held and made in good faith without malice. This attaches particularly to book reviews, or the critical appraisal of plays and films, but may also apply to comments made about politicians or other public figures. Such a defence also has to show that the remarks are based on demonstrable facts not misinformation.

In British law, to repeat a libellous statement made by someone else is no defence unless that person enjoys ‘absolute privilege’, as in a court of law or in parliament. Even so, reports of such proceedings have to be fair as well as accurate and if the statement made turns out to be wrong and an apology or correction is issued, this too is bound to be reported. A defence of ‘qualified privilege’ is available to reports of other public proceedings such as local authority council meetings, official tribunals, company annual general meetings open to the public, and other meetings to do with matters of public concern. The same defence may be used in relation to a fair and accurate report of a public notice or statement issued officially by the police, a government department or local authority. Where no ‘privilege’ exists, the broadcaster is as guilty as the actual perpetrator of the libel. Producers and presenters of the phone-in should be constantly on their guard for the caller who complains of shoddy workmanship, professional incompetence, or worse, on the part of an identifiable individual. An immediate reference by the presenter to the fact that ‘well, that’s only your view’ may be regarded as a mitigation of the offence, but the broadcaster can nevertheless be held to have published the libel.

The law also impinges directly on the broadcaster in matters concerning ‘official’ secrets, elections, consumer programmes, sex discrimination, race relations, gaming and lotteries, reporting from foreign courts and copyright.

The individual producer, in whatever country he or she is working, should remain aware of the major legal pitfalls and must have a reliable source of legal advice. Without it the station is likely, sooner or later, to need the services of a good defence lawyer.

From all the events and stories of the day how does the broadcaster decide what to include in the news bulletin? A decision to cover, or not to cover, a particular story could, itself, be construed as bias. The producer’s initial selection of an item on the basis of it being worthy of coverage is often referred to as ‘the media’s agenda-setting function’, and is a subject for much debate. People will discuss what they hear on the radio and are less likely to be concerned with topics not already given wide currency. So is a radio station’s judgement as to what is significant worth having? If so, the process of selection, the reasons for rejection, and the weight accorded to each story (treatment, bulletin order and duration) are matters that deserve the utmost care.

There is sufficient evidence to support the significance of the primacy and recency effects in communication. This means that items presented at the beginning of a bulletin have greater influence than those coming later – also that the final statements exert an inordinate bearing on the total impact – probably because they are more easily recalled. These principles are made much use of in debates and trials but clearly apply also to bulletins, interviews and discussions. Who speaks first and who is allowed the last word is often a matter of some contention.

The broadcaster’s power to select the issues to be debated – and their order of presentation – represents a considerable responsibility. Yet, given a list of news stories, a group of editors will each arrive at broadly similar running orders for a news bulletin designed for a particular audience. Are there any objective criteria on this matter of news values?

The first consideration is to produce a news package suited to the style of the programme in which is it broadcast, answering the question, ‘What will my kind of listener be interested in?’ A five-minute bulletin can be a world-view of 20 items, superficial but wide ranging; or it can be a more detailed coverage of four or five major stories. Both have their place, the first to set the scene at the beginning of the day, the second to highlight and update the development of certain stories as the day proceeds. The important point is that the shape and style of a bulletin should be matters of design and not of chance. Unlike a newspaper with its ability to vary the type size, radio can only emphasise the importance of a subject by its placing and treatment. A typical five-minute bulletin may consist of eight or nine items, the first two or three stories dealt with at one minute’s length, the remainder decreasing to 30 seconds each or less. The point was made earlier that, compared with a newspaper, this represents a very severe limitation on total coverage.

Having decided the number and the length of items, the news producer has to select what is important as opposed to what is of passing interest. When time is short, it is easier to gain the interest of the listener with an item on the latest scandal than with one on the state of the economy. The second item is more significant for everyone in the long term, but requires more contextual information. The producer must not be put off by such difficulties, for it is the temptation of the easy option that leads to some justification in the charge that ‘the media tends to trivialise’. An effect of the policy that news must always be available at a moment’s notice is that stories of long-term significance do not find a place in the bulletin. It is, after all, easier to report the blowing up of an aircraft than the development of one.

As already noted, a key criterion for selection is to favour items to do with people rather than things. The threat of an industrial dispute affecting hundreds of jobs will rate higher than a world record price paid for a painting. ‘How could this event affect my listener?’ is a reasonable question to ask. For the listener to a small station in Britain, 10 deaths following an outbreak of the Ebola virus in Cameroon would possibly be regarded with less significance than a serious local road accident. But should it? You don’t have to wait for local doctors to volunteer to go to West Africa before you see the significance of the story. Particularly in local radio there is a tendency to run something because of its association with immediate mayhem and disaster rather than its wider relevance. A preoccupation with house fires and traffic accidents, otherwise referred to as ‘ambulance chasing’, is to be discouraged.

News values resolve themselves into what is of interest to, or affects, the listener. More significantly, ‘interesting’ is determined by what is:

• important – events and decisions that affect the world, the nation, the community, and therefore me;

• contentious – an election, war, court case, where the outcome is yet unknown;

• dramatic – the size of the disaster, accident, earthquake, storm, robbery;

• geographically near – the closer it is, the smaller it needs to be to affect me;

• culturally relevant – I may feel connected to even a distant incident if I have something in common with it;

• immediate – events rather than trends;

• novel – the unusual or coincidental as they affect people.

On a different scale, sport can be all of these.

News has been called ‘the mirror of society’. But mirrors reflect the whole picture, and news certainly does not do that. Radio news is highly selective; by definition it is to do with the unusual and abnormal but the basis of news selection must not be whether a story arouses curiosity or is spectacular, but whether it is significant and relevant. This certainly does not mean adopting a loftily worthy approach – dullness is the enemy of interest – it requires finding the right point of human contact in a story. This may mean translating an obscure but important event into the listener’s own understanding. A sharp change in the money markets will be readily understood by the specialist, but radio news must enable its significance to be appreciated by the man in the street. The job of news is not to shock but to inform. A broadcasting service will be judged as much by what it omits as what it includes.

The investigation of private conduct and organisational practice – and malpractice – is an important part of media activity. This is the watchdog function referred to earlier, particularly keeping an eye on those in positions of public trust. The role of the Washington Post in the Watergate exposé is a well-documented example. Radio too recognises that it is not enough to wait for every news story to break of its own accord – some, of genuine public concern, are protected from exposure simply because of the vested interests that work to ensure that the truth never gets out. It is therefore sometimes necessary to allocate newsroom effort to the process of research enquiry into a situation that is not yet established fact. The story may never materialise because insufficient fact comes to light. This will involve the station in some loss through unproductive effort, but it is nothing like the loss that will be suffered if the newsroom proceeds to broadcast a story of accusations that turn out to be false.

Government departments or commercial businesses involved in underhand dealings, public officials or others with power engaged in questionable financial practice, the rich and famous called to account for their sexual immorality – these are the most common areas of investigation. But who is to say what is underhand, questionable or immoral? While it might be possible to remain impartial in the reporting of news fact, the exposé inevitably carries with it an assessment of a situation against certain norms of behaviour. Such values are seldom purely objective. An investigation into the payment of a bribe in order to secure a contract may provoke a public scandal in one part of the world while in another it is simply the way in which business is conducted. In other words, investigation requires a judgement of some malpractice – of right and wrong. The reporter must therefore be correct on two counts – that the facts as reported stand up to later scrutiny, and that his or her own judgement as to the morality of the issue is subsequently endorsed by the listener, that is by society.

To enable the reporter’s own values to remain largely outside the investigation, the most fruitful approach is often to use the stated values of the organisation or person being investigated as the basis of the judgement made. Thus, a body claiming to have been democratically elected but which subsequently was shown to have manipulated the polls lays itself open to criticism by its own standards. The same is true of governments which, while happy to be signatories of agreements on the treatment of prisoners, also allow their armed forces to practise beatings and torture; or business firms which promise refunds in the event of customer complaint but which somehow always find a loophole to evade this particular responsibility. The radio station may have to represent the listener in cases of personal unfairness, or pursue the greater interests of society in the face of public corruption. But the broadcaster must be right. This takes patience, hard, wearying research, and the ability to distinguish relevant fact from a smokescreen of detail.

Occasionally, outside pressure will be brought to bring the enquiry to a halt. This could be the signal that someone is getting uncomfortable and that the effort is beginning to bear results. It is surprising how often malpractice breeds dissatisfaction. Once the fact of an investigation becomes known, a person with a grudge is likely to provide anonymous information. Such ‘leaks’ and tip-offs of course need to be checked and treated with the utmost caution. A story that is told too soon will fall apart as surely as one that is wrong. Further, a station must resist the temptation to get so involved with a story that it falls prey to the same malpractice – although perhaps on a much smaller scale – as it is attempting to expose. So does it pay for information? Does it go in for surreptitious recording, to get the words of an illegal arms dealer or dubious estate agent – does it impersonate a potential buyer, for instance? Yes, this might be necessary, but should be sanctioned by senior management given all the facts. Does it jeopardise its own integrity by giving false information or staging events in the hope of laying a trap for others? Again, perhaps so, but investigative reporters should not work alone, but in twos or threes – to argue through the methods, develop theories and assess results. Guidelines suggest:

• the story should be sufficiently vital to justify deception;

• this should be the only way of getting the story;

• the listener must be told how the story was obtained.

Reporters will be wise to stay in close contact with their management – whose backing and continuing financial support are crucial. When it works, the effects are immediate and considerable. The reputation gained by the programme and station are incalculable. A ‘scoop’ puts competitors nowhere. The public at large wants wrongs put right. People respect a moral order, especially for others, and in the end prefer justice to expediency.

Programmes, and their station or network, cease to be objective or impartial when they wholeheartedly promote a particular course of action. The extent to which any such bias will threaten the credibility of the station as a whole depends on the proportion of the audience that will already agree with the action proposed. Thus a local station that wants to raise money for handicapped children is unlikely to create opposition among its listeners. Even if the newsroom originates the campaign, the standing of the normal bulletin material will probably remain unaffected. If, however, the station is advocating action on a more contentious issue – the publication of lists of convicted paedophiles, the introduction of random breath checks as a deterrent to drunken drivers, or mandatory blood sampling to detect carriers of the AIDS virus – then the station must expect opposition from those who prefer more liberty, some of whom will criticise any story on the subject which the station carries.

In general, campaigning is best kept away from the newsroom. The news editor should be allowed to pursue the professional reporting of daily factual truth without being involved in considerations of what other people – governments, councils, advertisers or radio managements – want reported, or unreported. This at least minimises the danger of one programme’s editorial policy jeopardising news credibility. Voices associated with news almost always run some risk when they appear in another broadcasting context. Journalists who lend weight to a particular view, however worthy, easily damage their reputation as dispassionate observers. Thus it was a group of campaigning Zambian women, not the newsroom, that broadcast a programme on the need for clean water that persuaded the authorities to drill new boreholes.

A producer wanting to promote a cause must obviously seek the backing of management and be aware of the possible effect of any campaign on other programmes, especially news. Partiality of view in itself may become counter-productive to the very issue it is supposed to promote.

The reporter out on the street and the sub-editor at the newsdesk are the people who make the decisions about news. Their concerns are accuracy, intelligibility, legality, impartiality and good taste.

Before looking at the key principles it is important to say something about one of the more difficult aspects of the job.

Most of the work is relatively straightforward; some of it is routine. Chronicling events and the reasons for them requires much rewriting of other people’s copy received by a multitude of means. It entails hours spent on the phone checking sources, and days out on location recording interviews and filing reports. It is during these times away from the newsroom, when the reporter is working alone, that there is a need for some self-sufficiency – an apparent self-confidence, not always felt – to tackle the unknown and sometimes dangerous situation.

A reporter’s first duty is to get the facts right. Names, initials, titles, times, places, financial figures, percentages, the sequence of events – all must be accurate. Nothing should be broadcast without the facts being double-checked, not by hearsay or suggestion but by thorough reliability. ‘Return to the primary source’ is a useful maxim. If it is not possible to check the fact itself, at least attribute the source declaring it to be a fact. Under pressure from a tight deadline, it is tempting to allow the shortage of time to serve as an excuse for lack of verification. But such is the way of the slipshod to their ultimate discredit. Even in a competitive situation, the listener’s right to be correctly informed stands above the broadcaster’s desire to be first. The radio medium, after all, offers sufficient flexibility to allow opportunity for continuing intermittent follow-up. Indeed, it is ideally suited to the running story.

Sometimes accuracy by itself is not enough. With statistics, the story may be not in their telling but in their interpretation. For instance, according to the traffic accident figures the safest age group of motorbike users is the ‘over 80s’ – not one was injured last year! So a story concerning a 20 per cent increase in the radioactivity level of cows’ milk over two years may be perfectly true, but is it significant? How has it varied at other times? Was the level two years ago unusually low? Were the measurements on precisely the same basis? And so on. Statistical claims always need care.

Accuracy is required too in the sounds that accompany a report. The reporter working in radio knows how atmosphere is conveyed by ‘actuality’ – the noise of a building site, the shouts of a demonstration. It is important in achieving impact and establishing credibility to use these sounds, but not to make them ‘bigger’ than they really are. How fair is it then to add atmospheric music to an interview recorded in an otherwise silent café? It may be typical of the café’s music (and it is useful in covering the edits) – but is it honest and real? Is it right to add small-arms fire to a report from a battle area? Typically it is there, it was just that the guns happened to be silent when I was recording. In other words does the piece have to be reality, or to convey reality? The moment you edit you destroy real-time accuracy. It is a question of motive. The accurate reporter, as opposed to a merely sensationalist one, will need a great deal of judgement if the object is to excite and interest, but not mislead.

The basic structure for the news interviewer is first to get the facts, then to establish the reasons or cause lying behind them, and finally to arrive at their implication and likely resultant action. These three areas are simply past, present and future – ‘What’s happened? Why do you think this is? What will you do next?’ At another level, a news story is to do with the personal motives for decision and action, and it is these which have to be exposed and, if need be, challenged with accurate facts or authoritative opinion quoted from elsewhere.

Intelligibility in the writing

Conveying immediate meaning with clarity and brevity is a task that requires refinement of thought and a facility with words. The first requisite is to understand the story so that it can be told without recourse to the scientific, commercial, legal, governmental or social gobbledegook which can often surround the official giving of information. A reporter determined to show a familiarity with such technicalities through their frequent application has little use as a communicator. News must be the translator of jargon not its disseminator.

In recognising where to start it’s necessary to have an insight into how much the listener already knows and how ideas are expressed in everyday speech. In being understood, the reporter’s second requirement is therefore a knowledge of the audience – it is unwise to deal only with colleagues and professional sources, for you could find yourself subconsciously broadcasting only to them. If the audience is distant rather than local, then from time to time travel among them, or at the very least set up whatever means of feedback is possible.

The third element in telling a story is that it should be logically expressed. This means that it should be chronological and sequential – cause comes before effect:

Not: ‘Two thousand jobs are to be cut, the XYZ Bank announced today.’

But: ‘The XYZ Bank today announced it was to cut two thousand jobs.’

The key to intelligibility, therefore, is in the reporter’s own understanding of the story, of the listener and of the language of communication.

Putting these three aspects together the news writer’s job is to tell the story, putting it in an understandable, logical sequence, answering for the listener questions such as:

• ‘What has happened?’

• ‘When and where did it happen?’

• ‘Who was involved?’

• ‘How did it happen and why?’

The first technique is to ensure that of these six basic questions, at least three are answered in the first sentence:

1 The Chancellor of the Exchequer told parliament this afternoon that he would be raising income tax by an average of 4 per cent in the autumn. (who, where, when, what, when)

2 Eight people were killed and over 60 seriously injured when two trains collided just outside Amritsar in northern India in the early hours of this morning. (what, where, when)

The second and subsequent sentences should continue to answer these questions:

1 He said it would be applied only to the upper tax bands and would not affect the basic rate. In answer to an opposition question he said this was necessary to reduce the government deficit. (how, who, why)

2 The crowded overnight express from Delhi was derailed and overturned by a local freight train as it left a siding near Amritsar station. Railway workers and police are still taking the injured from the wreckage and it is feared that the death toll may rise. (how, what)

A fault commonly heard on the air, which we looked at in Chapter 6, is that of the misplaced participle.

‘The Prime Minister will have to defend the agreement he signed, in the House of Commons.’

Without the comma this sounds as though we are talking about an agreement he signed in the House of Commons. But no, the story means:

‘The Prime Minister will have to defend in the House of Commons the agreement he signed.’

This error is frequently made in references to time.

‘He said there was no case to answer last July.’

What was actually meant was:

‘He said last July there was no case to answer.’

And another, following a report of child abuse by a nanny.

‘There was a demand to register all nannies with local councils.’

But what, you might ask, about nannies who are not with local councils? This would be better as:

‘There was a demand for all nannies to be registered with local councils.’

Two more examples from real life:

‘Action has been taken against the hospitals which removed the organs of patients who have died, without the knowledge or permission of their relatives.’

‘The government has agreed to allow a variety of GM maize to be grown.’

These ambiguities have to be removed. In the first it must be made clear that it is the removal of organs that was without the knowledge of relatives, and not the patients’ death. In the second, it sounds as though lots of different maize crops would be allowed. A subsequent bulletin changed this to ‘a single variety’.

Radio requires intelligibility to be immediate and unambiguous.

The reporter does not select ‘victims’ and hound them, does not ignore those whose views are disliked, pursue vendettas, nor have favourites. He or she does not promote the policies of sectarian interests, resists the persuasions of those seeking free publicity, and above all is even-handed and fair in presenting different sides of an issue. Expressing no personal editorial opinion, but acting as the servant of the listener, the aim is to tell the news without making moral judgements about it. Broadcasting is a general dissemination and no view is likely to be universally accepted. ‘Good news’ of lower trade tariffs for importers is bad news for home manufacturers struggling against competition. ‘Good news’ of another sunny day is bad news for farmers anxiously waiting for rain. The key is a careful watch on the adjectives, both in value and in size. Superlatives may have impact but are they fair? News may report an industrial dispute but what right does the reporter have to describe it as ‘a serious industrial dispute’? On what grounds may he refer to a company’s ‘poor record’, or a medical research team’s ‘dramatic breakthrough’? Words such as ‘major’, ‘crucial’, and ‘special’ are too often used simply to convince people that the news is important. Much better to leave the qualifying adjectives to the actual participants and for the news writer to let the facts speak for themselves.

Reporters are occasionally concerned that they might not be able to be totally objective since they have received certain inbuilt values from their upbringing and education. While it may be true that broadcasting has more of its fair share of people from middle-class families and with a college education, a reporter should be aware of any personal motivations of background and experience, recognising that others might not share them. Certainly what must be watched is any conscious desire to persuade others to think the same way.

Unlike the junior newspaper journalist, whose every last adjective and comma can be checked before publication, the broadcast reporter is frequently alone in front of the microphone. To help guard against the temptation of unintended bias, reporters should not be recruited straight from school, but have as wide and varied a background as possible and preferably bring to the job some experience of work outside broadcasting. It is sensible to ensure that any significantly large ethnic group in the community is represented in the broadcasting staff. The matter of bias is something on which members of the station’s board should keep a watchful ear.

In avoiding needless offence there must first be a professional care in the choice of words. People are particularly sensitive, and rightly so, about descriptions of themselves. The word ‘immigrant’ means someone who entered a country from elsewhere, yet it tends to be applied quite incorrectly to people whose parents or even grandparents were immigrants. Human labels pertaining to race, disability, religion or political affiliations must be used with special care and never as a social shorthand to convey anything other than their literal meaning. Examples are ‘black’, ‘coloured’, ‘Muslim’, ‘guerrilla’, ‘southern’, ‘Jewish’, ‘communist’, etc. – used loosely as adjectives they tend to be more dangerous than as specific nouns.

The matter of giving offence must be considered in the reporting of sexual and other crimes. News is not to be suppressed on moral or social grounds but the desire to shock must be subordinate to the need to inform. The journalist must find a form of words which, when spoken, will provide the facts without causing embarrassment, for example in homes where children are listening. With print, parents can divert their children from the unsavoury and squalid; in radio an immediate general care must be exercised at the studio end. A useful guideline is for the broadcaster to consider how actually to express the news to someone in the local supermarket, with other people gathered round.

More difficult is the assessment of what is good taste in the broadcasting of ‘live’ or recorded actuality. Reporting an angry demonstration or drunken crowd when tempers are frayed is likely to result in the broadcasting of ‘bad’ language. What should be permitted? Should it be edited out of the recording? To what extent should it be deliberately used to indicate the strength of feeling aroused? There are no set answers; the context of the event and the situation of the listener are both pertinent to what is acceptable. However, in using such material as news, the broadcaster must ensure that the motive is really to inform and not simply to sensationalise. It might be ‘good copy’, but does it genuinely help the listener to understand the subject? If so it might be valid but the listener retains the right to react as he or she feels appropriate to the broadcaster’s decision.

News of an accident can cause undue distress. It is necessary only to mention the words ‘air crash’ to cause immediate anxiety among the friends and relatives of anyone who boarded a plane in the previous 24 hours. The broadcaster’s responsibility is to contain the alarm to the smallest possible group by identifying the time and location of the accident, the airline, flight number, departure point and destination of the aircraft concerned. The item will go on to give details of the damage and the possibility of survivors, but by then the great majority of air travellers will be outside the scope of the story. In the case of accidents involving casualties, for example a bus crash, it is helpful for listeners to know to which hospital the injured have been taken or to have a telephone number where they can obtain further information. The names of those killed or injured should not normally be broadcast until it is known that the next of kin have been informed.

A small but not unimportant point in bulletin compilation is the need to watch for the unintended and possibly unfortunate association of individual items. It could appear altogether too callous to follow a murder item with a report on ‘a new deal for butchers’. Common sense and an awareness of the listener’s sensitivities will normally meet the requirements of good taste but it is precisely in a multi-source and time-constrained process, which news represents, that the niceties tend to be overlooked.

Civil disturbance and war reporting

Tragedy should be reported in a sombre manner – the broadcaster always remaining sensitive to how the listener will react. When reporting on a riot or commentating from a battle zone it is the reporter’s task to report and, as far as possible, not to get involved. It is sensible therefore always to get local advice on conditions and, as far as possible, to stay outside a disturbance, rather than try to work from inside the mêlée. It is then possible to see and assess what is happening as the situation develops. Under these conditions the reporter should remain as inconspicuous as possible and not add to or inflame the situation by his or her presence.

The primary ambience in a crisis is likely to be one of confusion. Asking for an official view tends to produce either optimistic hopes or worst fears, so any comment of this kind should be accurately attributed, or at least referred to as ‘unconfirmed’. Apart from the scene as it is ‘now’, analysis and interpretation of an event takes two forms – the pressures and causes which led up to it, and the implications and consequences likely to stem from it. Unless the reporter is very familiar with the situation, it is best to leave reasons and forecasts to a later stage, and probably to others. On the spot, there is no room for speculation: the story should be told simply on the basis of what the reporter sees and hears, or knows as fact – even then it may be necessary to withhold the names and identities of people involved in a kidnapping or police siege.

Prior to reporting from an actual war zone, the essential reading is UNESCO’s Handbook for Journalists. Originally published in French by Reporters Sans Frontières, it covers all the experience learned in recent years, especially from Afghanistan and the Middle East, but applies to all situations of danger and political instability. It is linked with the World Index of Press Freedom listing the documents intended to protect human rights and professional ethics (see Chapter 5). In practical terms it covers everything from vaccinations to the avoidance of land mines and booby-traps, being taken hostage, through to post- assignment counselling. It is very detailed.

In actual hostilities an accredited war reporter will be required to wear a flak jacket or other protective clothing – the military do not like to be held responsible unnecessarily for their own civilian casualties. This raised a particular ethical point concerning the war in Iraq.

Reports were filed by hundreds of journalists travelling with the American and British forces. The word ‘embedded’ was used for this integration. The advantage was that this gave the reporters the protection and some of the communication facilities of the military, and afforded access to the daily briefings. The disadvantage was that they were only given the information and movement that the coalition forces wanted them to have. It was up to the base station to restore some kind of objectivity. Reporters who wanted to travel independently had a tough time of it; some were killed in the crossfire.

In any case, under these circumstances it is necessary to liaise closely with the officer in charge and to accept limits sometimes on what can be said. Facts may have to be with held in the interests of a specific operation – for example, the size and intent of troop movements. This is for fairly obvious tactical reasons and it is generally permissible to say that reporting restrictions are in force. One of the now most memorable reports to come out of the Falkland Islands conflict arose from just such a situation. Brian Hanrahan reporting from the deck of the British aircraft carrier Hermes:

At dawn our Sea Harriers took off, each carrying three 1,000-pound bombs. They wheeled in the sky before heading for the islands, at that stage just 90 miles away. Some of the planes went to create more havoc at Stanley, the others to a small airstrip called Goose Green near Darwin, 120 miles to the west. There they found and bombed a number of grounded aircraft mixed in with decoys. At Stanley the planes went in low, in waves just seconds apart. They glimpsed the bomb craters left by the Vulcan and left behind them more fire and destruction. The pilots said there’d been smoke and dust everywhere punctuated by the flash of explosions. They faced a barrage of return fire, heavy but apparently ineffective. I’m not allowed to say how many planes joined the raid, but I counted them all out and I counted them all back. Their pilots were unhurt, cheerful and jubilant, giving thumbs-up signs. One plane had a single bullet-hole through the tail – it’s already been repaired.

(Courtesy of BBC News)

Expressed in a cool unexcited tone, it is worth noting the shortness of the sentences and ordinariness of the words used. It is not necessary to use extravagant language to be memorable (see also the section on live commentary in Chapter 19).

Working in conditions of physical danger, a basic knowledge of first aid is invaluable. Several organisations equip their staff reporting from areas of potential risk with a medical pack containing essentials such as sterile syringes, needles and intravenous fluid. Psychological as well as bodily safety remains important and reporters faced with violence, and the mutilated dead and dying – whether it be the result of a distant war or a domestic train crash – can suffer trauma for some time afterwards as a result of their experiences. The sometimes harrowing effects of news work should not be underestimated and the opportunity always provided for suitable counselling.

Almost every broadcasting station ultimately stands or falls by the quality of its news and information service. Its ability to respond quickly and to report accurately the events of the day extends beyond just news bulletins. The newsroom is likely to represent the greatest area of ‘input’ to a station and, as such, it is the one source capable of contributing to the whole of the output. Unlike a newspaper that directs its energies towards one or two specific deadlines, a radio newsroom is involved in a continuous process. The main sources of news coverage can be listed as:

1 Professional: staff reporters and specialist correspondents, e.g. crime, local government; freelances and ‘stringers’; computer, fax and wire services; news agencies; syndicating sources including other broadcasting stations; newspapers.

2 Official: government sources both national and local; emergency services such as police, fire and hospitals; military and service organisations; public transport authorities.

Figure 7.2 Newsroom and production office at BBC Radio Solent. Each desk has a DAW for downloading audio, mixing and editing for final packages

3 Commercial: business and commercial PR departments; entertainment interests.

4 Public: information from listeners, taxi drivers, etc.; voluntary organisations, societies and clubs.

There is a danger that in basing its news too much on press releases and handouts, a station is too easily manipulated by government and business interests. The output begins to sound like the voice of the establishment. An editor will become wary of material arriving by hand from an official source just before a major deadline. Of course, a handout provides ‘good’, one-sided information – that is its purpose. It needs to be evaluated and cross-examined and questions asked about implications as well as immediate effects. A newsroom must be more than just a processor of other people’s stories. The same is true of lifting items from newspapers – always look for new angles, and follow up if a story has appeared elsewhere, develop it, don’t run it as it is, take it further.

The heart of the newsroom is its diary. This may be in book form or held on computer. As much information as possible is gleaned in advance so that the known and likely stories can be covered with the resources available. The first editorial meeting of each day will review that day’s prospects and decide the priorities. Reporters will be allocated to the monthly trade figures, the opening of a new airport or trunk road, the controversial public meeting, the government or industry press conference, the arrival of a visiting head of state, or the publication of an important report. The news editor’s job is to integrate the work of the local reporters with the flow of news coming in from the other sources available, balancing the need for international, national or local news. But the news editor must also consider how to deal with the unforeseen – an explosion at the chemical works, a surprise announcement by a leading politician, a murder in the street. A newsroom, however, cannot wait for things to happen, it must pursue its own lines of enquiry, to investigate issues as well as report events.

Local newsrooms are sometimes tempted to select bulletin items in terms of geographical coverage – going for 20 stories representative of the area, rather than 10 items of more universal interest. This should be resolved in the form of a stated policy – that is, the extent to which a newsroom regards itself as serving several minorities as opposed to one audience of collective interest; The first is true of a newspaper, where each reader selects items of personal interest; the second is more appropriate to radio, where the selection is done by the station. Given considerably less ‘space’ the fewer stories have to be of interest to everyone.

The competent newsroom has to be organised in its copy flow. There should be one place which receives the input of letters, texts, tweets, emails, press releases and other written data. A reporter making ‘routine’ calls to the emergency services or other regular contacts collects the verbal information so that, after consulting the diary, the news editor can decide which stories to cover. A meeting in person or by phone then discusses the likely prospects, especially with specialist correspondents. One person will be allocated to write, or at least edit, the actual bulletins – a task not to be regarded as a committee job. If possible other writers are put on the shorter bulletins and summaries. Working from the same material, a two-minute summary needs a quite different approach. Omitting the last three sentences of each story in a five-minute bulletin will not do!

Reporters and freelances are allocated to the stories selected; each one is briefed on the implications and possible ‘angles’ of approach, together with suggestions for its treatment, and given a deadline for completion. Elsewhere in the room or nearby, material is edited, cues written, recordings are made of interviews over the phone, and previous copy ‘subbed’, updated or otherwise refreshed for further use. The mechanical detail will depend on the degree of sophistication enjoyed by the individual newsroom – the availability of a radio car or other mobile live inject equipment, OB and other ‘remote’ facilities, incoming lines, electronic data processes, off-air or closed circuit television, updated stories permanently available via computer screens in the studios, intercom to other parts of the building, etc.

In addition to all this the fully tri-media newsroom will not only be looking after the television side of things but may also have journalists to feed a variety of teletext, subtitle and website services.

A newsroom also requires systems for the speedy retrieval of information from a central file store. The computerised newsroom links together the diary information with ‘today’s’ prospects, the current news programme running orders and bulletin scripts. Local is joined to national. Everyone has the same information updated at the same instant. The presenter in the studio has the latest news material constantly available, reading it from the screen. There may also be a physical file of newspaper cuttings or old scripts. For the short-term retention of local information, the urgent telephone number or message to a colleague on another shift, a chalk-board or similar device is simple and effective.

The important principle is that everyone should know exactly what they have to do to what timescale, and to whom they should turn in difficulty. The news editor or director in overall charge must be in possession of all the information necessary for him or her to control the output, and be clear on the extent to which the minute-by-minute operation is delegated to others. There is no place or time for confusion or conflict.

There are many different kinds of smartphones, tablets, cell phones and other portable digital devices which can be extremely useful when reporting away from the studio base. Audio quality varies, and often radio stations will recommend a particular device and network. They will also install additional equipment at base to enable the devices to be connected to the studio desk to provide cue and talkback. Some stations will allow the use of output from these devices straight on air, as the BBC does on some occasions. It must be remembered these consumer devices are using a public digital cell phone network, and therefore reception may vary due to location and time of day and could be subjected to signal variability or even break-up or loss. The reporter needs to hear the cue programme in order to go ahead, and as cell circuits are two-way the cue feed can be switched from the studio, often with the addition of studio talkback. All portable devices are improved by plugging in a professional mic, but if this is not available the basic quality can be improved by talking across the device to avoid distortion and ‘pops’. Given the right app, such as Voice Memo, Viddio, or WavePad, the device can record and do multi-track editing. It can also do Internet research, make a phone call, or send a text back to the editor. It has the additional advantage of appearing ‘normal’, so in a situation of tension it doesn’t draw attention to itself, thereby making the reporter’s job safer. The cell phone – much improved by using an external mic with a windshield – offers great ease and flexibility of location reporting.

One of the editor’s jobs is to maintain the collection of rules, guidelines, procedures and precedents that forms the basis of the newsroom’s day-to-day policy. It is the result of the practical experience of a particular news operation and the wishes of an individual editor. The style book is not a static thing but is altered and added to as new situations arise. A large organisation will issue guidelines centrally which its local or affiliate stations can augment.

Sections on policy will clarify the law relating to defamation and contempt of court. It will define the procedure to be followed, for example, in the event of bomb warnings (whether or not they are hoax calls), private kidnapping, requests for a news black-out, the death of heads of state, observance of embargoes, national and local elections, the naming of sources and so on.

The book sets out the station’s mission or purpose statement and the role of news within that. It will indicate the required format for bulletins, the sign-on and sign-off procedures, the headline style, correct pronunciation of known pitfalls, and the policy regarding corrections, apologies and the right or opportunity of reply. It will list on-station safety regulations, as well as provide advice on proper forms of address. Above all there will be countless corrections of previous errors of grammar and syntax – from the use of collective nouns to the use of the word ‘newsflash’.

On arrival, the newcomer to a newsroom can expect to be given the style book and told to ‘learn it’.

The larger station will have a car, reserved for newsroom use, which the editor will send out with a reporter to cover a particular story. Some may be equipped with a telescopic mast capable of communicating back to the base station. Others will have a satellite dish (see p. 248). The principles of using mobile facilities tend to be similar whatever their design, and the following forms a common basis for routine operation:

Figure 7.5 BBC Radio Norfolk radio car with mast partly extended. The reporter wears a hi-vis jacket

• ensure a proper priority procedure for every vehicle. Who controls and sanctions its use? Who decides if a booking is to be overridden to cover a more important story? Have all potential users been fully trained and do they know these procedures? Are they up to date with any modifications, or minor faults affecting the vehicle’s operation?;

• remember that you are driving a highly distinctive vehicle. Whatever the hurry, be courteous, safe and legal;

• before leaving base, check that all necessary equipment is in the car, that the power supply batteries are in a good state of charge, and that someone is ready to listen out for you;

• switch on the two-way communications receiver in the car so that the base station can call you. Tune the car radio to receive station output;

• on arrival at the destination, take great care to avoid obstructions, such as overhead power and telephone lines, when using a telescopic mast. Set up the necessary link. Call the station and send level on the programme circuit;

• agree the cue to go ahead, duration of piece and handback. Check that you are hearing station output on your headphones;

• after the broadcast, replace all equipment tidily and lower the mast before driving off (cars with telescopic masts should have safety interlocks to prevent movement with the mast extended). Leave the communications receiver on until back at base in case the station wishes to call you;

• radio vehicles attract visitors; make sure vehicles are safely parked day and night.

Every car should be put ‘on charge’ when at base, and never garaged with the fuel tank less than half-full. It should carry a cell phone, area and local street maps, SatNav, a radio mic, a reel of cable for remote operation, spare headphones, batteries and a fuel can, extension leads, a pad of paper, a clipboard, a pencil, a cleaning cloth and a torch.

Distance from the station, of course, creates no problems in the use of the Internet, either for sending text via email or reports and interviews in digital form. This method of communication is used by the network of news correspondents worldwide. In addition, ISDN lines – the Integrated Services Digital Network – offer a relatively low-cost system using telephone circuits for high-quality voice transmission, where such circuits are provided. The reporter plugs a microphone or recorder playback into an ISDN ‘black box’ (Codec) which encodes the signal in digital form. The system works well for speech and may be ‘stretched’ for music.

Where phone lines are unreliable – providing a cell phone signal or reliable WiFi connection is available – a laptop or tablet and smartphone is the only kit required to get fully edited and packaged interviews and reports immediately on air from anywhere in the world.

However, while the high-tech solution may seem attractive, the reporter working away from base soon learns to become self-reliant when it comes to his or her technical equipment. It is often the low-tech which saves the day – the Swiss army knife or the collection of small screwdrivers. Everything has a back-up.

Experienced overseas reporters rely on such items as:

• battery recording machines – solid state recorders are robust and good for quick editing. A four-track recorder with two additional mic/line inputs capable of internal mixing;

• robust omni mics with built-in windshield;

• a small folding mic stand for use on a table;

• a lip mic to exclude untreated room acoustics or for use while travelling in a car;

• at least one long mic cable for putting a mic up-front for speeches or press conferences;

• assorted plugs and leads, including crocodile clips for connecting to phone lines;

• a smartphone with windshield and tablet with appropriate apps;

• waterproof insulating tape, gaffer/sticky tape;

• solar-powered or wind-up battery chargers can be useful for devices with integrated or rechargeable batteries. Cigarette lighter charging and power leads too, when in cars;

• headphones or an ear piece for monitoring and receiving the cue programme from a cell phone;

• an international double adaptor telephone plug. This is useful to be able to turn a single telephone socket, e.g. in a hotel room, into two for simultaneous connection of a telephone and a playback recorder;

• a radio – FM/MW/LW/SW with extra wire for an aerial;

• spare batteries, cards, leads, etc.

Such kit is invariably carried in a clearly labelled, tough foam-padded metal or high-impact plastic flight case – it is never left out of sight.

The news conference and press release

News conferences, company meetings, official statements and briefings of all kinds invariably set out to be favourable to those who hold them.

This is particularly so in the realm of politics. Ministerial aides, political advisers, press secretaries, public relations spokespersons, spin-doctors and the like abound. Their job is to create a positive appearance for all proposals and action – and to suppress the negative.

It is important therefore to listen carefully to what is being said – and what is not being said – and to ask key questions. Having been given facts or plans for action, the question is ‘why?’ It is necessary to quote accurately what is said – not difficult with a recorder – and to attribute the spokesperson or source. What is being said may or may not be totally true – what is true is that a named person is saying it.

Press releases, publicity handouts, notices and letters descend on the editor’s desk in considerable quantity. Most end up on the spike, unused – although if it is not suitable for a bulletin, a well-organised newsroom will offer a story to another part of the output. From time to time editors are asked to define what should go into a press release and how it should be laid out. The following guidelines apply.

1 The editor is short of time and initially wants a summary of the story, not all the detail. Its purpose is to create interest and encourage further action.

2 At the top should be a headline which identifies the news story or event.

3 The main copy should be immediately intelligible, getting quickly to the heart of the matter and providing sufficient context to highlight the significance of the story – why it is of interest as well as what is of interest, e.g. ‘this is the first 16-year-old ever to have won the award’. The writing style should be more conversational than formal; avoid legal or technical jargon.

4 Double-check all facts: names (first name and surname), personal qualifications, titles, occupations, ages, addresses, dates, times, places, sums of money, percentages, etc.

5 End with a contact name, office of origin, postal and email address, telephone numbers (including a home number), website, date and time of issue.

6 On paper or sent as a PDF document it should be typed, double-spaced with broad margins, on one side of a standard size such as A4, with a distinctive logo or heading – or on coloured paper to make it stand out. When sending copies to different addresses within a radio station, this should be made clear. An embargo should only be placed on a press release if the reason is obvious – for example, in the case of an advance copy of a speech, or where it is sensible to allow time to digest or analyse a complex issue before general publication. Radio is an immediate medium and editors have no inclination to wait simply in order to be simultaneous with their competitors.

To sum up the business of news. Good journalism is based on an oft-quoted set of values – it must be accurate and truthful, it stems from curiosity, observation and enquiry, and it must do more than react to events, it must report how those events affect people. In attempting to be impartial and objective it must actively seek out and test views. It has to make sense of what has happened and what is happening, for readers, listeners and viewers – that is, it has to be in the public interest – resisting the pressures of politicians, advertisers and others who may wish to cast the world in a light favourable to their own interests or cause.

The journalist might want to be an influence for good – a watchdog for society exposing corruption, driven by an interest in life, a desire to inform, and a love of the language. The motivation could be to become known as a good writer – accurate and ordered, with a distinctive style. Suffice it to say that any society founded on democratic freedom of choice requires a free flow of honest news. It is totally pointless to run a broadcast news service unless it is trusted and believed.