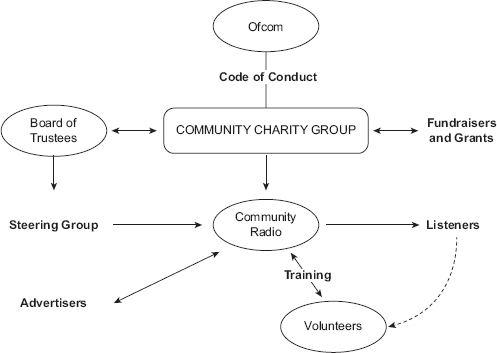

No radio station – and therefore no producer – exists in a vacuum. It has a context of connections, each one useful and necessary but also representing a source of potential pressure. Figure 2.1 illustrates some of these. At the top is the national regulator – the body with overall responsibility to its government for the supervision of all that country’s broadcasting services. There may be additional advisory bodies, sponsors and advertisers, community and educational interests, sources of information like the police and fire services, local councils, programme suppliers and supporters’ clubs. The station may be part of a large organisation or a media chain with other affiliate stations and a headquarters office. Every station is likely to have its own governing council, board, or owner, to whom the manager reports.

Figure 2.1 Stakeholders and interested parties around a typical station

Each of these bodies is linked here by two-way arrows – what do they represent? Is money changing hands – or information, or advice, or control? It is a good exercise for broadcasters to get to know their own situation.

Starting at the top, every country has an authority for the overall regulation of broadcasting. Their roles are very similar – they allocate station frequencies and set limits for transmitted power in order to avoid interference. They impose certain programme standards, set rules and monitor the output of stations to ensure these are kept. They do listener research. Here are three examples.

1 The Federal Communications Commission. Responsible to the US Congress, the FCC regulates all radio and television broadcasting, including inter-state and international satellite, broadband and cable services. It is the US’s primary authority for communications law and technical innovation. It states its vision as:

To promote innovation and investment, competition and consumer empowerment for the communications platforms of today and the future – maximizing the power of communications technology to expand our economy, create jobs, enhance U.S. competitiveness and unleash broad opportunity for all Americans.

Based in Washington DC, the Commission comprises a number of specialist committees. The Technological Committee deals with matters such as interference issues, security and industry standards. As far as the Internet is concerned the FCC says its aim is to:

Encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet; Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice; Consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement; Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

There are specific rules on broadcasting telephone conversations, broadcast hoaxes and equal opportunities. It prohibits programming that is obscene, indecent or profane. All sponsored material must be explicitly identified at the time of broadcast. The FCC has much to say about political programming. It has the power to inspect stations and insists that broadcasters keep station logs and records. It undertakes research into listening and viewing to determine how best to use the available frequency spectrum and adjust to technological development.

The FCC sets out its work in considerable detail on a well signposted website: www.fcc.gov.

2 The UK Office of Communication. Ofcom regulates all radio and television in the UK. Currently the BBC is responsible to its own Board of Trustees. However, this may change – in any case the Corporation must abide by the Ofcom Code. This ‘Broadcasting Code’ is required reading for all UK stations. The Code sets out to:

protect listeners from harmful and offensive content but also ensures that broadcasters have the freedom to make challenging programmes. For example, broadcasters can transmit provocative material – even if some people consider it offensive – provided it is editorially justified and the audience is given appropriate information.

As well as harm and offence, the Code covers other areas like impartiality and accuracy, fairness, privacy, protecting the under-18, elections and referendums, crime, religion, sponsorship and product placement.

It is a crucial aim of a commercial station to make a profit for its shareholders by selling advertising. However, their licence conditions require them to provide a certain amount of local programming. This is why Ofcom sets out its duties as:

• promoting the interests of citizens and consumers;

• securing a range and diversity of local commercial services which (taken as a whole) are of high quality and appeal to a variety of tastes and interests;

• ensuring for each local commercial station an appropriate amount of local material with a suitable proportion of that material being made locally.

Pursuing these objectives, Ofcom says that community stations receiving some advertising, sponsorship, and local grants must provide ‘social gain’ – that is, community information, news, weather, sport, events, etc. Ofcom carries out research into the way people use radio which shows that small-scale stations are ‘highly valued, fostering a real sense of belonging for which listeners have a unique sense of affection’. It showed that while people may not listen for great lengths of time, their level of engagement was high. Ofcom issues regular bulletins about its work. The website for details is: www.ofcom.org.uk.

3 The Australian Communications and Media Authority. ACMA is similar to the others on matters of frequency allocation and interference, has a list of prohibited programme content – transmitted or online – and has developed the Australian Internet Security Initiative to help address the problem of the surreptitious sending and installation of malicious software.

The Authority regulates advertising, which must be clearly distinguishable from other content. It has Codes of Practice concerning betting and gambling, and the incitement of violence, or hatred against a particular individual or group. It rules against anything that presents as desirable the misuse of alcohol, illegal drugs or tobacco. Programmes must not simulate news events in a way that could mislead or alarm, and ‘must not offend generally accepted standards of decency, having regard to the demographic characteristics of their audience’. Its equality policies require the use of terms such as ‘fire-fighter’ not fireman, similarly – police officer and sales rep., etc. Full details can be found at: www.acma.gov.au.

These examples serve to highlight the nature of the overall control which all national regulators have. Programme makers everywhere should make themselves aware of the requirements which apply to them – they are in general not overly restrictive but are in tune with the culture of the country.

Immediately in charge of the operation of the station is the manager or managing editor and his or her staff. This person is likely to be responsible to a local governing council or board.

To avoid constant misunderstandings and argument, the board’s terms of reference should be very precisely defined. Its job will depend on how the station is set up – its legal constitution. It may have a controlling function, deciding how the programming or finance should be determined, or its role may simply be advisory in assisting the station to meet its declared aims. It may play a part in appointing the staff; it should be ready to negotiate with outside bodies and always to protect the station against unfair criticism. If the station is run as a charity, the board will form the group of trustees responsible to the Charity Commission or other ruling authority.

It is a good idea for the working producer to know at least two members of the organisation’s board or council. Not only does this help the programme makers to appreciate the context within which the station is operating, but it also acquaints board members with the difficulties and encouragements experienced by those who actually create the product. Such introductions are best made through the manager.

Radio is often categorised and structured not so much by what it does as by how it is financed. Again, there is a wide variation in how a station gets its money, but each method of funding has a direct result on the programming which a station can afford or is prepared to offer. This, in turn, is affected by the degree of competition which it faces.

The main types of organisational funding are as follows:

• public service, funded by a licence fee and run by a national corporation;

• commercial station financed by national and local spot advertising or sponsorship, and run as a public company with shareholders;

• government station paid for from taxation and run as a government department;

• government-owned station, funded largely by commercial advertising, operating under a government-appointed board;

• public service, funded by government funds or grant-in-aid, run by a publicly accountable board, independent of government;

• public service, subscription station, does not take advertising and is funded by individual subscribers and donors;

• private ownership, funded by personal income of all kinds, e.g. commercial advertising, subscriptions, donations;

• community ownership, not-for-profit station often supported by local advertising and sponsors;

• institutional ownership, e.g. university campus, hospital or factory radio, run and paid for by the organisation for the benefit of its students, patients, employees, etc.;

• radio organisation run for specific religious or charitable purposes – sells airtime and raises income through supporter contributions;

• restricted Service Licence – RSL stations, on low power and having a limited lifespan to meet a particular need, e.g. one-month licence to cover a city festival.

The ability to charge premium rates for advertising depends either on having a large audience in response to popular appeal programming, or an audience with a high purchasing power for the individual advertiser. Competing for income from a limited supply is quite different from the competition which a station faces to win an audience.

Around the world, stations combine different forms of funding and supplement their income by all possible means, from profit-making events such as concerts, publishing, and the sale of programme downloads – both to the public and to other broadcasters – to the sale of T-shirts and CDs, community coffee mornings and car boot sales.

Finance directly affects a station’s structure, but given the vast range of audience requirements, from huge national and international organisations to very small community needs, it is not surprising that there is no such thing as a ‘typical station’. It is possible, however, to give some examples which generalise how things work – how the boss, manager, director, editor, advertising people, producers, reporters, operators, engineers, administrative staff and freelances work together to create a coherent output.

Here is what a commercial station might look like.

The station manager would be a member of the board of directors, or might be one of a group of station managers overseen by a senior programme controller or general manager.

The programme head is the deputy manager. The engineers look after the equipment and the IT aspect of the website, and even though it’s a self-op station, they may do studio operation for some of the freelance presenters. There’s generally a front of house receptionist, and the larger stations would have secretaries for the administrative logs and legal work, plus perhaps catering and cleaning staff. Security is often contracted out.

A BBC local station typically has a very flat management structure integrating the news output with the lengthy Sequence or Strip programmes across the day. They share the same office space or newsroom (see Figure 7.2).

The producers and broadcast assistants exist within the programme teams, together with the freelance contributors. There is a receptionist and secretarial staff as required. The engineering resource is often shared between several stations.

Like other non-BBC stations in the UK, community radio comes under Ofcom and has its own advisory and funding bodies (see Figure 2.2).

The purpose of a station such as this is not only to serve the community as listeners, but to involve local people in creating the output and to provide educational courses and music events. A fairly typical station – Future Radio in Norwich – has three full-time paid staff and some 120 volunteers. The full-time staff are: a station manager, an advertising coordinator (who is the deputy station manager) and a broadcast assistant. The advertising coordinator is in charge of commercial sales and promotional events, also supervising the production of trailers and commercials for broadcasting. The broadcast assistant looks after everything related to the studio, including scheduling, managing playlists, station IDs, studio bookings and helping the volunteers with the daily operations of the station. Because the radio station is part of an umbrella charity group it also shares the expertise of a salaried IT manager, who deals with IT and buildings, and a business support officer who helps with fund raising. There are also opportunities in a community station such as this for young people to apply for work-experience posts.

Figure 2.2 The typical community radio context

The Community Media Association is the UK representative and supporting body for this sector of broadcasting (www.commedia.org.uk). The manager of Future Radio talks about his job on the website.

A radio station should be a creative place. Programme makers are always wanting to win prizes and awards for what they do, but more important is the winning of an audience – and keeping it. As this book says more than once, it is about being relevant and engaging – knowing about your listeners and what motivates them. Not simply waiting for people to come to you, but reaching out to them – an idea never bettered than in the catchline of CBS station WINS in New York:

‘You give us twenty-two minutes – we’ll give you the world.’

Whether you are in a city area, an African township, a huge expanse of rural countryside, or across the Internet, you have to care about what concerns people – or makes them laugh – your listener is the be-all and end-all of your endeavour. Meeting those needs is a serious business requiring insight, accuracy and truth. But it should also be fun – an enjoyable pursuit to which you give much of your time and energy. Many are the broadcasters who have said, ‘It’s amazing, I actually get paid for doing what I like best.’ Of course there are rows and different opinions, competing for ratings, arguments over ideas and budgets. But the ideal working atmosphere has a certain amount of mutual support, of appreciating that the worth of a station is greater than the sum of its individual parts or programmes, and that everyone who works there, in whatever capacity, has a share in the final outcome.

There are hundreds of opportunities, so you’d think it would be easy to find a place somewhere in local radio or in hospital, student or community radio. The key is to acquaint yourself with what’s going on – the debates and issues on broadcasting. Read the trade magazines and reviews in newspapers, look at station websites, download recordings, get tickets for a show if you can, and of course listen to as much radio as possible – of all different kinds so that you know what suits you best.

Getting a job at a station means first of all understanding its structure, what its aims are, what kind of output it provides, what it needs, and how it works. Does the work involve television and website coverage as well as radio? The most likely way in is to offer to work as a freelance helper, or contributor of ideas and items and, if successful, move on to the staff as a programme assistant. Many successful broadcasters have started by making the tea – and doing so willingly. A station may offer an attachment to begin with, or an internship – paid or unpaid. If so, it is essential to get to know the equipment really well, understanding the software technicalities and processes of the studio. This can be very helpful to some of the established programme people, especially the older contributors. Station staff appreciate newcomers who are keen and enthusiastic, arrive on time, ask questions, come up with ideas and stay late to get things finished.

If given a programme brief, however small, it is important to make sure your name is attached to it – programme credits are crucial to your subsequent CV. These count hugely if you are interviewed for a job – for which the key attributes are enthusiasm, and having done your homework.