Presentation is radio’s packaging. It hardly matters how good a programme’s content, how well written or how excellent its interviews; it comes to nothing if it is poorly presented. It would be like taking a beautiful perfume and marketing it in a medicine bottle.

Good presentation stems from an understanding of the medium and a basic concern for the listener. The broadcaster at the microphone should genuinely care whether or not the listener can follow and understand what he or she is saying. If a newsreader or presenter is prone to the destructive effect of studio nerves, it is best to ‘think outwards’, away from yourself. This also helps to counter the complacency of over-familiarity, and is therefore more likely to communicate meaning. Since it’s not possible to know the listener individually, adopt the relationship of an acquaintance rather than that of a friend.

The news presenter is friendly, respectful, informative, helpful – and personal. You know you have something to offer the listener, but this advantage is not used to exercise a knowledgeable superiority or to assume any special authority. The relationship is a horizontal one. We refer to ‘putting something across’, not down or up. In informing the listener we do not presume on the relationship but work at it, always taking the trouble to make what is being said interesting – and sound interesting – by ourselves being interested.

Of course, newsreading tends to be more formal than a music programme but there is room for a variety of approaches. Whatever the overall style of the station, governed by its basic attitude to the listener, it should be fairly consistent. While the sociologist may regard radio as a mass medium, the person at the microphone sees it as an individual communication – talking to someone. Thinking of the listener as one person it’s better to say, ‘If you’re travelling south today, . . .’ not ‘Anyone travelling south . . .’. The presenter does not shout. If you are half a metre from the microphone and the listener is a metre from the radio, the total distance between you is one and a half metres. What is required is not volume but an ordinary clarity. Too much projection causes the listener psychologically to ‘back off’ – it distances the relationship. Conversely, by dropping his or her voice the presenter adopts the confidential or intimate style more appropriate to the closeness of late night listening.

The simplest way of getting the style, projection and speed right is to visualise the listener sitting in the studio a little way beyond the microphone. The presenter is not alone reading, but is talking with the listener. This small exercise in imagination is the key to good presentation.

Here are the recognised basics of good presentation:

1 Posture. Is the sitting position comfortable, to allow good breathing and movement? Cramped or slouching posture doesn’t make for an easy alertness.

2 Projection. Is the amount of vocal energy being used appropriate to the programme?

3 Pace. Is the delivery too fast? Too high a word rate can impair intelligibility or cause errors. Too slow is ponderous and boring.

4 Pitch. Is there sufficient rise and fall to make the overall sound interesting? Too monotonous a note can quickly become very tiring to listen to. However, animation in the voice should be used to convey natural meaning rather than achieve variety for its own sake. So even if the pitch varies, is it forming a predictable repetitive pattern?

5 Pause. Are suitable silences used intelligently to separate ideas and allow understanding to take place?

6 Pronunciation. Can the reader cope adequately with worldwide names and places? If a presenter is unfamiliar with people in the news, or musical terms in other languages, it may be helpful to learn the basics of phonetic guidelines.

7 Personality. The sum total of all that communicates from microphone to loudspeaker, how does the broadcaster come over? What is the visual image conjured up? Is it appropriate to the programme?

The rate of delivery depends on the style of the station and the material being broadcast. Inter-programme or a continuity announcements should be at the presenter’s own conversational speed, for example newsreading at 160–200 words per minute, but slower for short-wave a transmission. Commentary should be at a rate to suit the action. If a reader is going too fast it may not help simply to slow down – this is likely to make the voice sound stilted and over-careful. What is required is to leave more pause between the sentences – that is when the understanding takes place. It is not so much the speed of the words that can confuse, but the lack of sufficient time to make sense of them.

The first demand placed on the newsreader is that he or she understands what is being read. You cannot be expected to communicate sensibly if you have not fully grasped the sense of it yourself. With the reservations expressed later about ‘syndicated’ material, there is little place for the newsreader who picks up a bulletin with 30 seconds to go and hopes to read it ‘word perfect’. So, be better than punctual, be early. Neither is technically faultless reading the same thing as communicating sense. A newsreader should be well informed and have an excellent background knowledge of current affairs in order to cope when changes occur just before a bulletin. Take time to read it out loud beforehand – this provides an opportunity to understand the content and be aware of pitfalls. There may be problems of pronunciation over a visiting Chinese trade mission, a Middle East terrorist, or a statement by an African foreign minister. There may be a phrase that is awkward to say, an ambiguous construction, or a typing error. The pages should be verbally checked by the person who, in the listener’s mind, is responsible for disseminating them. While a newsroom may like to give the impression that its material is the latest ‘hot off the press’ rush, it is seldom impossible for the reader to go through all the pages of a bulletin, on paper or off screen, as it is being put together. Thorough preparation should be the rule, with reading at sight reserved only for emergencies.

Of course in practice this is often a counsel of perfection. In a small station, where the newsreader may be working single-handed, the news can arrive within seconds of its deadline. It has to be read at sight. This is not the best practice and runs a considerable risk of error. It places on the syndicating news service, and on the sending keyboard operator, a high responsibility for total accuracy. The reason for poor broadcasting of on-screen material may lie with the station management for insufficient staffing, or with the news agency for less than professional standards. The fact of the matter is that in the event of a mistake on the air, from whatever cause, the listener blames the newsreader.

The person at the microphone, therefore, has the right to expect a certain level of service. This means a well-written, properly punctuated and set out bulletin, accurately typed, arriving a few minutes before it is needed. It’s then possible to check if the lead story has changed and scan it quickly for any unfamiliar names. Pick out figures and dates to make sure they make sense. In the actual reading, your eyes are a little ahead of your speech, enabling you to take in groups of words, understanding them before passing on their sense to the listener.

The idea of syndicated news is excellent but it should not become the cause nor be made the excuse for poor microphone delivery.

In the studio the newsreader sits comfortably but not indulgently, feeling relaxed but not complacent, breathing normally and taking a couple of extra deep breaths before beginning.

Here are some other practicalities of script reading:

• Don’t eat sweets or chocolate beforehand: sugar thickens the saliva.

• Always have a pen or pencil with you for marking alterations, corrections, emphasis, etc.

• If you wear them, make sure you have your glasses.

• Don’t wear anything that could knock the table or rattle – bangles, cufflinks.

• Place a glass of water near at hand.

• Remove any staples or paper-clips from the script and separate the pages so that you can deal with each page individually.

• Make sure you have the whole script; check that the pages are in the right order, the right way up.

• Give yourself space, especially to put down the finished pages – don’t bother to put them face down.

• Check the clock, cue light, headphones – for talkback and cue programme – and the mic-cut key if there is one.

• Check your voice level.

• Where timing is important, time the final minute of the script (180 words – perhaps 18 lines of typescript) and mark that place. You need to be at that point with a minute left to go and may have to drop items in order to achieve this.

• Once started, don’t worry about your own performance; be concerned that you are really communicating to your imagined listener, ‘just beyond the mic’.

• If reading from a screen connected to a local network, make sure it is secure and that a colleague on another terminal is not inputting to the news while you are broadcasting.

A station should, as far as possible, be consistent over its use of a particular name. Problems arise when its output comprises several sources, e.g. syndicated material, a live audio news feed, a sustaining service. What should be avoided is one pronunciation in a nationally syndicated bulletin, followed a few minutes later by a different treatment in a locally read summary. The newsroom must listen to the whole of the station’s news output, from whatever source, and advise the newsreader accordingly. Second, listeners are extremely sensitive to the incorrect pronunciation of names with which they are associated. The station that gets a local place name wrong loses credibility; one that mispronounces a personal name is regarded as either ignorant or rude. The difficulty is that listeners themselves might not agree on the correct form. Nevertheless, a station should make strenuous efforts to ensure a consistent treatment of place names within its area. A phonetic pronunciation list based on ‘educated local knowledge’ should be adopted as a matter of policy and a new broadcaster joining the staff, acquainted with it at the earliest possible time.

Alternatively, store correctly spoken pronunciations in audio form on a computer. It is then an easy matter for a presenter to bring a name up on screen and hear it being said.

An important aspect of conveying meaning, about which a script generally gives no clue at all, is that of stress – the degree of emphasis laid on a word. Take the phrase: ‘What do you want me to do about that?’

With the stress on the ‘you’, it is a very direct question. On the ‘me’, it is more personal to the questioner; on the second ‘do’, it is a practical rather than a theoretical matter; on the ‘that’, it is different again. Its meaning changes with the emphasis. In reading news such subtleties can be crucial. For example, we may have in a story on Arab/Israeli affairs the following two statements:

Mr Radim is visiting Washington where he is due to see the President this afternoon.

Meanwhile the Israeli Foreign Minister is in Paris.

(www.focalpress.com/cw/mcleish)

The name is fictional but the example real. Put the emphasis on the word ‘Israeli’, and Mr Radim is probably an Arab foreign minister. Put it on ‘Foreign’, and he becomes the Israeli Prime Minister. Try it out loud. Many sentences have a central ‘pivot’, or are counter-balanced about each other: ‘While this is happening over here, that is taking place over there.’ Many sentences contain a counter-balance of event, geography, person or time: ‘Mr Smith said an election should take place now, before the issue came up. Mr Jones thought it should wait at least until after the matter had been debated.’

Listening to newsreaders it is possible to discern a widespread belief that there is a universal news style, where speed and urgency have priority over meaning, where the emphasis is either on every word or scattered in a random fashion, but always on the last word in every sentence. Does it stem from the journalist’s need for clarity when dictating copy over the phone? The fact is that a single misplaced emphasis will cloud the meaning, possibly alter it.

The only way of achieving correct stressing is by fully understanding the implications as well as the ‘face value’ of the material. This must be a conscious awareness during the preparatory read-through. As has been rightly observed, ‘take care of the sense and the sounds will take care of themselves’.

The monotonous reader either has no vocal inflection at all, or the rise and fall in pitch becomes regular and repetitive. It is the predictability of the vocal pattern that becomes boring. A too typical sentence ‘shape’ starts at a low pitch, quickly rises to the top and gradually descends, arriving at the bottom again by the final full stop. Placed end to end, such sentences quickly establish a rhythm which, if it does not mesmerise, will confuse, because with their beginning and ending on the same ‘note’, the joins are scarcely perceptible. Meaning begins to evaporate as the structure disappears. However, in reality and without sounding artificial or contrived, sentences normally start on a higher pitch than the one on which the previous one ended – a new paragraph certainly should. There can often be a natural rise and fall within a sentence, particularly if it contains more than one phrase. Meaningful stressing rather than random patterning will help.

A newsreader is well advised occasionally to record some reading for personal analysis – is it too rhythmic, dull or aggressive? In the matter of inflection, try experimenting off-air, putting a greater rise and fall into the voice than usual to see whether the result is more acceptable. Very often when you may feel you are really ‘hamming it up’, the playback sounds perfectly normal and only a shade more lively. Even experienced readers can become stale and fall into the traps of mechanical reading, and a little non-obsessive self-analysis and experimentation is very healthy – alternatively, actively ask for the comments of others.

Reading quotes is a minor art on its own. It is easy to sound as though the comment is that of the newsreader, although the writing should avoid this construction. Some examples:

While an early bulletin described his condition as ‘comfortable’, by this afternoon he was ‘weaker’. (This should be rewritten to attribute both quotes.)

The opposition leader described the statement as ‘a complete fabrication designed to mislead’.

He later argued that he had ‘never seen’ the witness.

(www.focalpress.com/cw/mcleish)

To make someone else’s words stand out as separate from the newsreader’s own, there is a small pause and a change in voice pitch and speed for the quote.

Last-minute handwritten changes to the typed page should be made with as much clarity as possible. Crossings out should be done in blocks rather than on each individual word. Lines and arrows indicating a different order of the material need to be bold enough to follow quickly, and any new lines written clearly at the bottom of the page. To avoid confusion, a ‘unity of change’ should be the aim. It is amazing how often a reader will find their way skilfully through a maze of alterations only to stumble when concentration relaxes on the next perfectly clear page.

But what happens when a mistake is made? Continue and ignore it or go back and correct it? When is an apology called for? It depends, of course, on the type of error. There is the verbal slip which it is quite unnecessary to do anything about, a misplaced emphasis, a wrong inflection, a word that comes out in an unintended way. The key question is ‘could the listener have misconstrued my meaning?’ If so, it must be put right. If there is a persistent error, or a refusal of a word to be pronounced at all, it is better to restart the whole sentence. Since ‘I’m sorry I’ll read that again’ has become a cliché, something else might be preferred – ‘I’m sorry, I’ll repeat that’, or ‘Let me take that again’. It is whatever comes most naturally to the unflustered reader. To the broadcaster it can seem like the end of the world; it is not. Even if the listener has noticed it, what is needed is simply a correction with as little fuss as possible.

The reading of a list can create a problem. A table of sports results, stock market shares, fatstock prices or a shipping forecast – these can sound very dull. Again, the first job for the reader is to understand the material, to take an interest in it, so as to communicate it. Second, the inexperienced reader must listen to others, not to copy them, but to pick up the points in their style that seem right to use. There are particular inflections in reading this material which reinforce the information content. With football results, for example, the voice can indicate the result as it gives the score (www.focalpress.com/cw/mcleish). The same is true of racing results, which have a consistent format:

‘Racing at Catterick – the three thirty.

First, number 7, Phantom, 5 to 2 favourite,

Second, number 9, Crystal Lad, 7 to 1

Third, number 3, Handmaiden, 25 to 1

Non-runner, number 1, Gold Digger.’

For obvious reasons care must be taken over pronunciation and prices. A highly backed horse might be quoted at ‘2 to 5’. This is generally given as ‘5 to 2 on’.

In passing, it is worth noting that sport has a good deal of its own jargon which looks the same on the printed page, for instance the figure ‘0’. The newsreader should know when this should be interpreted as ‘nought’, ‘love’, ‘zero’, ‘oh’ or ‘nil’ – the listener will certainly know what is correct. Unless it is automatic to the reader, it is well worth writing the appropriate word on the script. Whenever figures appear in a script, the reader should sort out the hundreds from the thousands and, if necessary, write the number on the page in words.

If it has been correctly written, a script consists of short unambiguous sentences or phrases, easily taken in by the eye and delivered with clear meaning, well within a single breath. The sense is contained not in the single words but in their grouping. To begin with, as children, we learn to read letter by letter, then word by word. The intelligent newsreader delivers scripted material phrase by phrase, taking in and giving out whole groups of words at a time, leaving little pauses between them to let their meaning sink in. The overall style is not one of ‘reading’ – it is much more akin to ‘telling’.

In summary, the ‘rules’ of newsreading are:

1 Understand the content by preparation.

2 Visualise the listener by imagination.

3 Communicate the sense by telling.

Radio managers become paranoid over the matter of station style. They will regard any misdemeanour on-air as a personal affront, especially if they instituted the rule that should have been observed. It’s nevertheless true that a consistent station sound aids identification. It calls for some discipline, particularly in relation to the frequently used phrases to do with time. Is it 3.25 or 25 past 3? Is it 3.40 or 20 minutes to 4? Is it 15.40? Dates: is it ‘May the eleventh’, ‘the eleventh of May’, or ‘May eleven’? Frequencies, 1107 kilohertz, 271 metres medium wave, can be given in several ways: ‘on a frequency of eleven-oh-seven’, or ‘two-seven-one metres medium wave’, or ‘two-seventy-one’. Temperatures: Celsius, centigrade or Fahrenheit? Or just ‘22 degrees’?

Some stations insist on a very strict form of identification, some prefer variety:

• radio Berkely

• Berkely radio – two-seven-one

• the county sound of Berkely

• the sound of Berkely county

• Berkely county radio, etc.

Idents can be by station name, frequency or wavelength, programme title, presenter name, or by some habitually used catchline:

• GZFM – where news comes first

• GZFM – the heartbeat of the county

• GZFM – serving the South

• GZFM – with the world’s favourite music.

Learn the station policy and stick rigidly to it – even when sending in an audition tape, use the form you hear on-air.

A subtle facet of presentation is to remember that it is the presenter who joins the listener not the other way round. ‘It’s good to be with you’ is a personal form of service, whereas ‘Thank you for joining me’ is more of an ego-trip for the presenter. The station should go to the bother of reaching out to its listeners, not expect them to come to it.

Presenting a sequence of programmes, giving them continuity, acting as the voice of the station, is very similar to being the host of a magazine programme responsible for linking different items. The job is to provide a continuous thread of interest even though there are contrasts of content and mood. The presenter makes the transition by picking up in the style of the programme that is finishing, so that by the time he or she has done the back-announcements and given incidental information, station identification and time check, everything is ready to introduce the next programme in perhaps quite a different manner. Naturally, to judge the mood correctly it’s necessary to do some listening. It is no good coming into a studio with under a minute to go, hoping to find the right piece of paper so as to get into the next programme, without sounding detached from the whole proceedings. A station like this might as well be automated.

If there is time at programme breaks, trail an upcoming programme – not the next one, since you are going to announce that in a moment. The most usual style is to trail the ‘programme after next’. But do so in a compelling and attractive way so as to retain the interest of the listener – perhaps by using an intriguing clip from the programme (see p. 159). If the trail is for something further ahead, then make this clear – ‘Now looking ahead to tomorrow night . . .’.

Many programmes handover from one to the next, so that presenters may chat to each other at the break, or at least introduce what’s coming. A frequent rule of presentation is ‘never say goodbye’. It’s an invitation for the listener to respond and switch off. At the end of a programme the presenter hands over to someone else – you (the station) never give the impression of going away – even for a commercial break.

Continuity presentation requires a sensitivity to the way a programme ends, to leave just the right pause, to continue with a smile in the voice or whatever is needed. Develop a precise sense of timing, the ability to talk rather than ‘waffle’, for exactly 15 seconds, or a minute and a half. A good presenter knows it is not enough just to get the programmes on the air, the primary concern is the person at the end of the system.

What do you do when the computer fails to respond, the machine does not start or having given an introduction there is silence when the fader is opened? First, no oaths or exclamations! The microphone may still be ‘live’ and this is the time when one problem can lead to another. Second, look hard to see that there has not been a simple operational error. Are all the signal lights showing correctly? Is there an equipment fault that can be put right quickly? Is the item playing back on the computer? Is the right fader open? If by taking action the programme can continue with only a slight pause, five seconds or so, then no further announcement is necessary. If it takes longer to put right, 10 seconds or more, something should be said to keep the listener informed:

‘I’m sorry about the delay, we seem to have lost that Report for a moment . . .’

Then, if action has assured it is possible to continue:

‘We’ll have it for you shortly . . .’

The presenter may assume personal or collective responsibility for the problem but what isn’t right is to blame someone else:

‘Sorry about that, the man through the glass window here pressed the wrong button!’

The same goes for the wrong item following a particular cue, or pages read in the wrong order. The professional does not become self-indulgent, saying how complicated the job is; you simply put it right, with everybody else’s help, in a natural manner and with the minimum of bother. The job of presentation is always to expect the unexpected.

Sooner or later a more serious situation will occur which demands that the presenter ‘fills’ for a considerable time. Standby announcements of a public service type – an appeal for blood donors, safety in the home, code for drivers, procedure for contacting the police or hospital service. Also, the current weather forecast, programme trails and other promotional material can be used. These ‘fills’ should always be available to cover the odd 20 seconds, and changed once they have been used.

Standby music is an essential part of the emergency procedure. Something for every occasion – a break in the relay of a church service, the loss of Saturday football, an under-run of a children’s programme. To avoid confusion the music chosen should not be identical to anything it replaces, simply of a sympathetic mood. Once it is on there is a breathing space to attempt to get the problem sorted out. The principle is to return to the original programme as quickly as possible. Very occasionally it may be necessary to abandon a fault-prone programme, and some stations keep a ‘timeless talk’ or 15-minute feature permanently on standby to cover such an eventuality. For longer-term schedule changes see p. 348.

A vocal performer can sometimes become obsessed with the sound of his or her own voice. The warning signs include a tendency to listen to oneself continuously on headphones. The purpose of headphone monitoring is essentially to provide talkback communication, or an outside source or cue programme feed. Only if it is unavoidable should both ears be covered, otherwise presenters begin to live in a world of their own, out of touch with others in the studio. Remember, too, the possible danger to one’s hearing of prolonged listening at too high a level. There’s also a danger of getting into a rut if there is a great deal of routine work – the same announcements, station identifications, time checks and introductions. It becomes easy not to try very hard to find appropriate variations. Like the newsreader, all presenters should occasionally listen to themselves recorded off-air, checking a repetitive vocabulary, use of cliché or monotony of style.

Part of a station’s total presentation ‘sound’ is the way it sells itself. Promotional activity should not be left to chance but be carefully designed to accord with an overall sense of style. ‘Selling’ one’s own programmes on the air is like marketing any other product, and this is developed in Chapter 17, but remember that the appeal can only be directed to those people who are already listening. The task is therefore to describe a future programme as so interesting and attractive that the listener is bound to tune in again. The qualities that people enjoy and which will attract them to a particular programme are:

• humour that appeals;

• originality that is intriguing;

• an interest that is relevant;

• a cleverness which can be appreciated;

• musical content;

• simplicity – a non-confusing message;

• a good sound quality.

If one or more of these attributes is presented in a style to which he or she can relate, the listener will almost certainly come back for more. The station is all the time attempting to develop a rapport with the listener, and the programme trailer is an opportunity to do just this. It is saying of a future programme, ‘this is for you’.

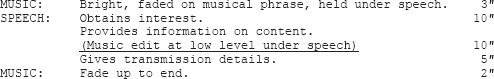

Having obtained the listener’s interest, a trail must provide some information on content – what the programme is trying to do, who is taking part and what form (quiz, discussion, phone-in, etc.) it will take. All this must be in line with the same list of attractive qualities. But this is far from easy – to be humorous and original, to be clever as well as simple. The final stage is to be sure that the listener is left with clear transmission details, the day and time of the broadcast. The information is best repeated:

‘You can hear the show on this station tomorrow at six p.m. Just the thing for early evening – the “Kate Greenhouse Saga”, on 251 – six o’clock tomorrow.’

Trails are often wrapped around with music which reflects something of the style of the programme, or at least the style of the programme in which the trail is inserted. It should start and finish clearly, rather than on a fade; this is achieved by prefading the end music to time and editing it to the opening music so that the join is covered by speech.

At its simplest, a trail lasting 30 seconds might look like this:

There is little point in ordering people to switch on; the effect is better achieved by convincing listeners that they are really missing out and suffering deprivation if their radio isn’t on. And, of course, if that is the station’s promise then it must later be fulfilled. Trails should not be too mandatory, and above all they should be memorable.

The website illustrates station trails from Future Radio, Norwich. The music comes from a specialist ‘mood music’ library, licensed by MCPS-PRS. A useful source to get to know (see p. 386).