A new way to look at and understand the journey to purchase

The increased power of the customer. The shopper/buyer has become more powerful because of two things: near universal communication (and the technology that has enabled it) and the access a shopper/buyer has to an amazing amount of information about brands, products and services. As a result, the shopper/buyer expectation has changed: quality, value, relationships, easy communication, competent service and delivery with consistency rank high in their evaluation of the brand, supplier and retailer.

The supplier, retailer and brand managers have to live with this, but if they use big data and social media research and the Insight obtained from these, they can discover a lot about the shopper/buyer: who they are; who buys what and how to communicate with them, with what messages; promotions and the media to use and the timing of those messages and, from measurement, what triggers the purchase. So it is possible to not only to keep up with customers but to reach ahead of them.

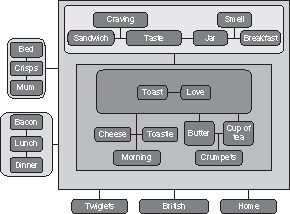

The shopper/buyer’s engram and ‘mind file’, and its role in shopping to the purchase point. Research has found that something in the brain, which shoppers do not articulate when questioned, prompts purchase decision behaviour. The shopper/buyer builds ‘mind files’ on his or her journey to purchase – about brands, products, services, around; let us call it a collection of ‘hooks’ (see Figure 3.1.) inside the subconscious part of the brain. Each hook is different for each shopper/buyer. A shopper/buyer looks for unique visual clues, prioritising shape and colour over any words for the hook they select; that is, a ‘hook’ is a logo, a smell, a category, a jingle, but usually a visual indicator called a Core Visual Mnemonic (CVM) that triggers a brand or product or service into the active part of the brain. The trigger brings forward the content of the hook when triggered (shown by the cogs) and displays the contents in the conscious brain (shown by the computer screen). All the experiences and messages, good or bad, as interpreted by the shopper, are added to their relevant ‘hook’. The ‘mind file’ accumulation on the ‘hook’ is identified as the engram.

Figure 3.1 Engram hooks

Source: Helmsmen Business Consultants

Only when a tipping point of sufficient and appropriate marketing communications is achieved, with messages that build the ‘mind file’ on that hook, will the shopper be persuaded to buy that brand, product or service. Each person has a different set of hooks, storing different experiences and their take on the marketing messages, in his or her subconscious ‘mind file’. The communication canvas of the shopper/buyer also has an impact (see Figure 3.2.). That is what a person understands from the marketing communications he or she receives, which can vary widely from person to person.

Figure 3.2 Communication and learning

Source: Helmsmen Business Consultants

The diagram illustrates how communication works. The overlap between sender and receiver is the realm of understanding. There is a normal simple feedback and a researched feedback with a check on whether the receiver is likely to really understand the communication and, as a consequence, the message is transformed to match the communication canvas of the recipient before being sent. A full explanation of all the hazards to communication that exist – and there are many – is available on the resource section of the IPM website. It is also included in Shoppernomics (see below).

Discovering the shopper view of a brand

For example, by categorising tweets in six or eight ways from happiness to disgust and examining each comment on every aspect reveals a generalised shopper/buyer view of a brand – the engram. This can then be compared to the brand, product or service preferred profile, known as a brandgram – that is, the image intended by the brand manager, retailer or supplier. Figure 3.3 is a brandgram for Marmite. Action or marketing communications can then be used to accommodate or correct anomalies found between the engram and brandgram.

Figure 3.3 Brandgram for Marmite

Source: Helmsmen Business Consultants

A brandgram for Marmite: what the brand manager wants the consumer to describe in his or her emotions, feelings and experiences of Marmite. Nearer the centre (and in the darker-shaded areas) are the higher preferences. An expansion of the reasoning for the engram/brandgram concept is given in Shoppernomics, a book by Roddy Mullin and Colin Harper, published by Gower.

How do you achieve the tipping point – that is, when is the decision to buy made? The answer is by providing the right number of messages through appropriate media channels. To build the engram ‘mind file’, some six marketing communications are needed to deliver appropriate messages:

1 Initial messages provide information, educate and come from the brand manager, retailer or supplier. They describe the product and associated services and the benefits and features. They must match the communication canvas in their delivery.

2 The shopper/buyer will also search other sources, online, forums, social media, Pinterest and Instagram, for information and comments – clever marketers encourage this. Some brands, such as WauWaa in the past (see Brief 3.1.), have used social media as the starting point for educating, making aware and instructing, and then introducing the commerce element.

3 Contacts with colleagues, friends and relatives need to be stimulated as they provide an important input to the mind file – sharing their views.

4 On the way to and in the shopping environment (online or in-store), the retailer should send messages to the shopper/buyer. Excess share of voice (ESOV) plays an important part and can be achieved locally quite easily. (ESOV is when the marketing communications proportionally exceed the market share versus competitors).

5 Point of sale material (and packaging) plays a further part.

6 Finally, promotions, both alongside each of the above communications and at the point of sale itself, are the icing on the cake, adding fun and exciting the shopper/buyer to achieve the tipping point that decides for him or her – make that purchase!

The shopper may be consciously smart, sophisticated, cynical of marketing and advertising, time scarce and highly selective, but his or her subconscious will be working the whole time.

BRIEF 3.1. Business model where ‘shoppers provide content’ to start-ups. WauWaa was a UK start-up which used social media as content; the company targeted first-time parents. The brief is included here as it is an example of not starting with an information campaign – one of the six marketing communications deemed essential by the author. The website allowed users to share parenting emotions, problems and experiences. The experience for both mums and dads is engaging, interesting and compelling. The company describe the model as ‘browsing and discovering’ (as you would shop in a mall) rather than the old ‘search and buy’. The company offered products (the website was changed three times a week) that were suggested by parents. Fifty-one per cent of first-time visitors to the site bought. Parents were encouraged to upload photos of the products in use (the products supplied, however, were photographed in a studio). Fifty-one per cent made contact with the site through a mobile (not a tablet).

The company aimed to give a loving experience. The key feature was to use real topics from real parents, of multi-cultural and multi-ethnic backgrounds, with a genuine passionate interest that covered topics such as pregnancy, birth and rearing children. Some 7,000 bloggers created the content. It was an engagement channel, not one seeking followers. Sadly the company suddenly vanished, leaving all sorts of problems, but it is an interesting business model which has great potential.

Craftsy.com uses a similar model for making items in wool and material, photography, art, baking and many other craft-based hobbies. Users share experiences and advice; the company supplies the materials and tools and offers inexpensive training courses.

Shopper/buyer: Hurdles for the retailer to understand

How does the shopper set about shopping?

A need arises, or the shopper’s mind file is triggered by a marketing communication which brings information stored in his or her subconscious to the active part of the brain. What catches the eye? What messages persuade? How does the shopper gather and use information? Price/value may be a trigger. The fact is that most thinking and decisions in-store are not purely rational; you have to accept that there is a degree of randomness about the way a person shops. This shopping experience is basically about a creative process, putting together a rationale for whether or not to buy. It is complicated by the 20 per cent of shoppers who are unpersuaded and unconcerned about price.

The trigger which kick-starts the shopper along the route to purchase can be almost anything – a comment by someone, reading a newspaper or magazine article, seeing something on TV or at the cinema or hearing something on the radio. A trigger may be one of the key words (‘new’, ‘free’, a £1 flash) or, of course, seeing the engram trigger. It may be a launch date (for the latest iPads), or when event tickets go on sale; either may also be the start point. A particular interest of the shopper in a category – say, clothing, technology, music – may mean that the shopper is easier to trigger and start his or her journey to purchase and – because the shopper has been along the path before – he or she travels the route faster, particularly if the brand, supplier or retailer communicates appropriate messages (that match the stages – see below) along the way.

Once on the route to purchase, there are four generally acknowledged stages:

• taking in (absorbing) information; this is often subliminal and uses the subconscious;

• positively researching the proposed purchase by comparing alternatives (planning);

• setting out and completing the buying mission (obtaining); and

• assessing the merits and value of the purchase (sharing – passing information to other shoppers).

The customer applies a different buying process to different category purchases. Obviously, acquiring a pair of socks (and commodity shopping) may require no thought or use of the mind file and allows an instant purchase, where the product subsequently can be rejected if the purchase is mistaken. There are not many parameters when considering a sock (or commodity) purchase.

When buying a car, a rigorous examination of alternatives, consultations and research is undertaken; for example, the cost of insurance, tax and fuel consumption in addition to performance, reliability and resale price. In fact, car salespeople report that some shoppers know more about the car than they do – all the shopper is then looking for from the salesman is a better deal than from a competitor car showroom. Factors affecting the shopper’s perception may be the cost of the purchase in relation to the shopper’s income, available cash or credit – but here, the salesperson can invoke feelings that the shopper is worth it and can overcome price resistance.

BRIEF 3.2. Don’t assume anything! The salesperson must not assume anything about the shopper or whether he or she can, for example, afford to buy. Pity the Swiss sales girl who reckoned Oprah Winfrey was unable to pay for a handbag.

The shopper’s emotional state and status perception at the time of purchase can encourage or deter impulsiveness. Heightened emotion associated with a promotion, work, professional recognition, being on holiday or being in love can encourage the shopper/buyer to bypass normal caution and restraint. (So make the shopper/buyer happy!) The status and newness of products and services may also influence a purchase; some customers are heavily influenced by the signals a branded or new item portrays and their own perception of how people view others that own such branded goods.

A customer attitude to purchase can be altered by the perception of an economic recession, the influence of green issues, medical disclosures, press speculation and whether he or she can be seen to shop in certain premises. The extended recession made economy-brand shopping quite chic for otherwise high net worth individuals; shopping at Lidl or Aldi with an Audi, BMW or Range Rover is no longer socially unacceptable.

Segmentation: Does it apply?

Who buys what? Can you still segment? Yes and No! Customers display many different shopping personalities according to the time, place or context of the purchase. The business executive may be buying top travel packages one moment, and the next, organising an economy family break. Within a few hours, an office manager may be purchasing office materials, spending on entertainment at lunchtime with colleagues and then, after leaving work, going food and retail shopping with the children before returning home to shop online. The shopper/buyer is still one individual with a singular and distinct social, educational and cultural background, but represents multiple customer personalities. The supplier or retailer that fails to recognise this chameleon-like facility is likely to fail the customer relationship test.

To target by gender, demographic or socioeconomic station is no longer adequate; ultimately, brand marketers must reach, engage, convert and amplify the Offer (see below) to the specific shopper – the one who will buy, share, post, tweet and participate in branded programs and events. The shortest path to this shopper is through a well-targeted, measured and well-messaged existing user base. The importance of well-planned and holistic CRM practices has never been greater.

BRIEF 3.3. CRM. Customer service is expected to be extremely shopper friendly – yet still some retailers’ account-driven processes can put off customers for good. Typical are the mobile phone companies (examples here are Virgin Media and Vodafone) who, when banks for example make errors with direct debits, do not inform customers of impending doom, but just cut off broadband or mobile access at a whim. This should of course in future be taken as affecting the customers’ human rights, as so many government services require an online response, and if a mobile phone company cuts off the line and the broadband, the customer is totally bereft. Such experience, though, costs customer numbers and all the potential customers that they then tell in the long run. It is as bad as a shopper discovering that the stock for a sales promotion has run out. (Waitrose is bad at sales promotion stock running out.)

BRIEF 3.4. Segmentation and treatment of the shopper/buyer. Myer (Australia), advised by Sarah Richardson of Global Loyalty Pty Ltd. (see Part IV), segments its customers under five categories, according to the way they shop as much as on the basis of what they buy:

• Busy Belinda: always in a hurry and often with kids;

• Premium Polly, who loves designer and high-end trends;

• Trendy TJ: would be and wants to be Premium Polly;

• Low-Involvement Lou, who would rather not shop if she can help it;

• Discount Dora, who loves to snag a bargain.

This has helped its marketers and staff in assessing how to treat shoppers.

Finding your target shoppers and obtaining Insights

Research from eBay shows some 75 per cent of UK shopping spend is by ‘super shoppers’ who make up 18 per cent of the population (see separate brief on super shoppers). For top-end products and services, these wealthy persons must be sought out, but the same applies to other types of shoppers who have an interest in any specific product ranges. Lists exist, and for many years it has been possible to construct a profile of a preferred customer and then find potential customers with similar profiles and the channels to reach them. Those with a sport or hobby or specific need will generally search out their niche suppliers and retailers.

BRIEF 3.5. A city financial services firm’s clients were analysed, and only 10 out of hundreds were found to be very high net worth, with a further 18 being high net worth. Seventy-two more were potentially valuable; the bulk of clients generated very little commission income (the 20:80 Pareto rule applied). The top 28 were profiled, and across the city a further 20,000 with a similar profile were found. These identified high-value clients were targeted as a segment at a rate of 200 per year, with 20 new clients sought per year. Interestingly, they all preferred to pay on a fee basis rather than a commission basis for the financial services offered. The fee income was considerably larger than the sum obtained from the previous commission-based operation. Subsequently, the same fee basis service was applied to solicitors’ practices with similar success – ‘retainerships’ are preferable to paying commission, for many segments of professional clients. Oh, and the hundreds of other financial services clients – they were ‘sold’ to another firm.

Future shapers. Those who lead the pack, the future ‘shapers’, must also be identified among customers and then engaged with. Future shapers are identified as:

• valuing authenticity and originality in all they buy and experience;

• being well informed and hugely involved in the products, services and thus brands they buy;

• individualistic, doing things their way and trying to persuade suppliers to convert to that way;

• time-poor and valuing anything that saves them time;

• socially responsible, exercising ethical awareness via product and brand choices;

• curious, open-minded and receptive to new ideas;

• advocates of new ideas – and they spread the word.

Ruthlessly apply self-recognition criteria. Before you go any further, for every customer segment that you decide to select as a target (you do not need to target every one), you should apply the following method. Erase from your mind your own thinking and prejudices. Learn to listen, observe and grasp how your target thinks, communicates and comes to conclusions. You need to understand them and how they react. This method has been described as ‘self-recognition criteria’ – accepting that the way you think and react is certainly wrong for any target you are analysing.

You should not make any assumptions about the target customer (research into marketers finds their assumptions about customers are grossly out of kilter with reality). Find out from analysis of big data and the Insight from research. Now that there exists an open mind about the customer, let’s examine how to respond to the customer.

Hazards to the shopper/buyer journey

An in-store environment is immensely complex, with often some 25,000 products on display and several thousand promotions, other shoppers and staff; so how does the shopper set about the task of making purchases? A product and its packaging need to stand out, and to do so in a very brief glance by the shopper, and seeing a CVM triggers the engram with its ‘mind file’. Shoppers are pack-focussed, and interacting with packs is the primary task.

Unfortunately, market researchers are often unaware that the research they undertake exposes conscious attitudes and opinions to research stimulus material but rarely identifies the subconscious. Eye tracking studies, for example, reveal where people look on a pack, but with honourable exceptions, such as iMotions, studies do not reveal whether a dwell in one area is a result of trying to understand, or of high levels of interest.

A website can also be complex. The design and path through the webpages needs to deploy CVM pointers early to reassure and guide the shopper/buyer.

The results of encounters with advertising. Brands used to rely on killer messages in their advertising (such as ‘last day of sale’, ‘final reduction’). Shoppers are generally immune to messages that are unrelated to a category in which they are interested (see Brief 2.3). Brands have tried to use killer messages with social media, but the shopper no longer swallows the bait there either. Just 6 per cent of a brand’s fans engage through Facebook via likes, comments and polls. The Facebook Edgerank algorithm decides which news feed items to put in front of a subscribing shopper. The algorithm considers the affinity (relevance to the shopper), weight (pictures and video carry more weight) and time decay of the news item. This means only a few will see a news feed.

Until brands understand that social media is a network of influencers rather than a target, such advertising will be ineffective; the brand needs to embrace the empowered shopper, encouraging the influencers to comment on the brand – and favourably. For the shopper, advertising has to be useful, building positive relevant experiences. In the future, those marketing brands need to engage, respecting the shopper while allowing him or her to participate in the brand experience. The key concept here is experience – something such as the opportunity to compete in an online game or contribute to a sport, activity or hobby. The impact of this activity depends on the stage the customer is at on his or her journey to purchase, the particular media and how the customer is connected to the media – the device he or she is using (whether it is capable of viewing items, whether it is GPS enabled) – a key element of the shopper’s profile nowadays.

At the point of sale, there is an involvement in purchase, dialogue, developing the customer relationship and ‘nudging’ the customer as a shopper to purchase – and MARI research (POPAI’s Marketing at Retail Initiative) has discovered that what actually can and does make the difference to the purchase decision is the use of key words (‘free’, ‘new’ or a £1 flash) or a promotion. Research, remember, indicates that 70 per cent of brand purchase decisions are made in-store/on the webpage.

A retail outlet such as a supermarket, which is tied to a location and offers a standard range of brands, or a niche product supplier needs to establish what the local shoppers’ profiles are (or the niche segment shopper’s characteristics are) and what they buy, and then stock that range and similar brand lines. Centralised management does not work for such retail outlets and the local manager must have the power to acquire shopper Insight and then decide what to stock, the promotions to run and the messages to communicate (Lidl seems to be good at this).

BRIEF 3.6. Lidl and Aldi. These are discount supermarkets with limited stock – typically 1,700 UPCs – which are carefully matched to the local shoppers. Visit three Lidl shops, for example – say at Cirencester, Clapham and Stockwell. The latter is full of commodity items. Clapham has some upmarket items. Cirencester has plenty of more luxury items. It makes common sense; grocers in Knightsbridge will stock and sell champagne, but there is much less call for it in other parts of London.

Can you deliver? Stock availability – logistics. Increasingly, a failure to stock is a source of potential disgust to shoppers. Shoppers expect to see their preferred brands on shelf. Shops and retail outlets are often centrally limited in the inventory they may stock, even though outlets may do so (M&S will supply only 10 stores with some fashion items; Homebase limits boards for cutting at some of its stores, meaning customers have to go elsewhere). Meanwhile other chains are prepared to move stock around (TopShop spends millions doing so – but they rate customer satisfaction highly). Next, too, seems to have cracked the problem.

BRIEF 3.7. Mis-stocking. One fashion chain went out of business some years ago through failing to research its customers – jackets with sleeves were stocked in the North of the UK and sleeveless jackets sent to the South – customers in each case preferred the opposite, and a fortune (over £1 m), more than their profit, was spent correcting the error through redistributing stock – the promise was next-day delivery to store. The chain did not appreciate that Northerners think jackets with arms are for softies, while Southerners want value for money, i.e. jackets with arms.

The Offer

The six Cs – the Offer. The six Cs components are:

• Cost(of lifetime purchase) within a value perception. That value perception is personal and includes a quality-of-life assessment; social, cultural or status reasons; and the cost of time and travel to make a purchase, in addition to longer-term servicing and maintenance costs.

• Concept – the product and service, incorporated with brand values, benefits and advantages over competitors; a warranty, fitness for purpose and a returns policy are assumed and, of course, there is the distinctive shopper marker – its engram (and the subconscious ‘mind file’ built on it – more on this in the next but one paragraph).

• Convenience – of payment method, location, availability of the item and, ideally, 24/7 purchase and delivery – the mobile, tablet and internet are the latest technical aids that add to the convenience of searching and finding your concept.

• Communication – the seamless arrival of appropriate and timely messages through preferred media and channels. The communication must not be complex or too dull, and must put the concept across in terms the consumer commonly uses. The mobile internet is the consumer technology of the future – nearly all of the population own at least one mobile – and, remember, shoppers communicate with each other (social media) and expect the brand to operate two-way communication, too.

• Customer relationship – the customer expects to have a relationship, be treated with respect and be recognised at any interface (the involvement criteria) by the supplier or retailer, with all reasonable questions answered and problems arising resolved speedily and fairly.

• Consistency – the same values of the brand and messages at all customer interfaces – brand surety, if you like. Research shows that inconsistency can lead to a loss of 30 per cent of sales.

Matching the Offer to the shopper/buyer

Once the Offer is determined, it needs to be matched to what the shopper/buyer expects. This is an iterative process. If the shopper buys from the Offer and the CVP you have created – if it is right – then you will make sales!

BRIEF 3.8. Short-term changes. A promotion is particularly helpful when your firm is making short-term changes to one or more parts of the whole Offer and communicating that to customers. Examples are when a different-coloured Smartie is included in the pack for a short time, or KitKat is produced in a mint flavour (a change in the concept). It alters the cost to the customer, for instance when a lager brand is sold as ‘33 per cent extra free’ or when a product is sold with a 10 p-off flash. It can announce a change in convenience, for example when Guinness is sold at summer fêtes, well away from its normal licensed trade outlets – all in the interests of influencing behaviour now. If you book a flight with easyJet on the internet, you receive a sales promotion, an instant discount that may have been the subject of newspaper publicity or an advertisement or a direct mailshot driving the customer to the web.

Action points

How should a retailer react to the shopper?

1 First, anchor your proposition as the supplier, brand manager or retailer for each product or service, using the customer view of the six Cs component parts of the Offer (see next section) and produce the Customer Value Proposition (CVP) – relating it to the CVM for marketing communications.

2 Second, ensure that you locate and understand who your target shoppers are and, from Insight, know that the Offer you propose matches the six Cs components for your target shoppers. You may have to change the Offer to achieve alignment or find a way to realign your shoppers to your Offer.

3 Third, take account of the recent research finding that has exposed the part the shopper’s subconscious plays when they are choosing what to buy – which requires a sequence of messages delivered by different media to build the ‘mind file’ of the shopper, achieve locally an ‘excess share of voice’ and reach the shopper’s tipping point that persuades him or her to buy (adding a promotion!). The Insight should also be used to confirm that the shopper’s engram and ‘mind file’ for your product or service is near what you would wish for your brand – compare their version with your brandgram. If it is not as you would wish, you will need to act to remedy this with additional messaging.

4 Fourth, of course, make sure you have the logistics in place to deliver your product or service and any promotion – customers are really put off if a brand they seek isn’t in stock.

When the four have been considered, there is a clear way ahead for the marketer to define marketing objectives (see Chapter 2) and so make a plan for message communication through each medium. From that analysis process readily arises the promotional objectives – ‘Who do you want to do what?’ (see Chapter 12) – along the route to purchase that converts the shopper’s arrival at the tipping point into a sale, which is what this book is about.

Undermining customer loyalty to competitor products: what promotions are most influential? Coupons or vouchers have the greatest effect (55 per cent buy a product they would not have otherwise), followed by in-store tasting, then a money-saving discount. Samples in any form work well, whether given away in store with other products or through door drops – even cover-mounted on magazines.

Moneysupermarket.com has estimated that some 2.4 million vouchers are redeemed every day, representing £30 billion in a year. The positive impact of a coupon on customer buying behaviour even works when the value of the coupon is small – research indicating that there is no difference in response between a 15 p-off or a 75 p-off coupon or voucher.

Measuring the effectiveness of all the above is a challenge, and is covered in Chapter 15. Real-time intelligence, where the brand and retailer pick up shopper reaction almost as it happens, is needed to turn the quantities of data into relevant actionable ‘Insight’, transforming the end-user experience positively into purchases.

How can the retailer benefit from measurement? Good news for those who use data in-store and online at all stages of the path to purchase!

Bronto surveyed retailers under three categories: store-focused (only 20 per cent revenue from online), online focused (>50 per cent) and e-mail-driven (40 per cent of their business from email) retailers took differing actions pre-purchase, in purchase and after purchase.

Online focussed

Pre-purchase data. A retailer’s pre-purchase communications are based on activities that signal that a consumer is shopping, but has not necessarily made a selection or is ready to purchase. This is a critical part of the purchase process because, when done well, retailers have the maximum opportunity to influence consumer shopping behaviour.

Browsing data. The 53 per cent of retailers who do collect product-level browsing data, however, are already leaps and bounds ahead of their competitors: they collect a large number of data points. Of those who do collect product-level data (product category and specific product, price, product details, ratings or reviews, quantity, image URL), more than 80 per cent of respondents leverage product category and SKU (stock-keeping unit) information when using browsing data to target e-mail communications. What is interesting is how few retailers are leveraging product images: only 59 per cent. This is a vastly missed opportunity, as market research has continually shown that images have far greater suggestive impact on consumers than text. Eighty-four per cent then send an automated e-mail response.

Transaction data. In-purchase activities move shopping behaviour from browsing to the transaction itself. For retailers looking to build repeat business, an important point of continuity is in using the transaction as a bridge to driving the next sale. Of those retailers who send transactional messages, most only send order and shipping confirmations. Fewer than one in four retailers are taking advantage of the revenue-driving potential and customer service engagement opportunities of a multi-e-mail post-purchase series. Even though 75 per cent of respondents automate data exchange between their e-commerce platform and their e-mail service provider, 34 per cent are not able to use that information to market to shoppers in the purchase cycle. For those who can leverage the data, they are nearly evenly split between the ability to use only e-mail-related purchase data (32 per cent) and data attributed to both e-mail and non-e-mail-related purchases (34 per cent). While possessing the data is a first step, actually using the data can be a challenge. Of those who collect purchase-related data, nearly half (42 per cent) have not actually used the data in e-mail communications.

Post-purchase. Once the purchase is completed, retailers should begin enticing that consumer to make his or her next purchase and become a loyal customer. What we see instead is that while retailers are interested in continuing the dialogue with a hopefully happy customer, those communications tend to not be very imaginative, focusing primarily on inactive purchasers (vs. recent purchasers) and doing basic segmentation of past purchasers. Only 24 per cent will customise campaigns to active purchasers beyond their transactional communications of order and/or shipping confirmations. The percentage is slightly higher, 31 per cent, among online-focused retailers, showing again that retailers who conduct the majority of their business online are more willing to experiment with communications that go beyond “standard operating procedure.” It would seem that the scope for retailers to make shed-loads more sales is enormous.

BRIEF 3.9. Future of retail is in ‘bricks and clicks’, says John Lewis. How we Shop, Live, Look reports that “Contrary to some headlines, we don’t think that online shopping is replacing the high street, our shoppers tell us they still enjoy shopping as a leisure activity. John Lewis continues to draw customers with shop sales up.”

BRIEF 3.10. What will stores of the future be like? Thomson’s new-look shop in Bluewater features a video wall shop window, an 84” touch-screen interactive map and high-definition screens and projections throughout the store offering changing images and videos, with content ranging from live weather information to reviews and destination videos.

BRIEF 3.11. The super shopper. Eighteen per cent of people account for 70 per cent of total UK retail sales (equivalent to over £200 billion in 2013) according to a study by eBay and Deloitte. They shop frequently, showroom and compare prices by browsing online. Retailers need to target these people to boost their sales in all channels, the marketplace reveals.

The role of influencers. Customers are influenced by others when making purchases, and this influence must be understood. Viral marketing depends on this. You need to know how those around the customers, the people they follow and their perceived status, can influence their attitude and their buying behaviour. Social media, celebrities, a panel of experts – from a game show? TV soap? Cookery competition? Car testing programme (such as Top Gear?) – are all influencers to different customers.

B2B Buyers are shoppers too!

Oracle (September 2012) reports that business-to-business (B2B) customers now expect their provider to be accessible online with a user-friendly, B2C-like experience – for example, accepting text messages as purchase orders.

Screwfix takes orders from builders directly and delivers to site. This is copying the just-in-time work practices of manufacturing – a proven cost-saving measure for the builder – and enhancing the direct sales for Screwfix.

Forrester Research reports that “many B2B companies project that e-commerce will soon comprise 50% of total sales.”

In summary: B2B should follow B2C practice. With more competition and tighter budgets than ever before, a business needs to:

1 Identify the ideal customer – produce a profile.

2 Find lists of firms that match the profile as marketing targets.

3 Define a sales-qualified lead and the marketing processes to nurture him or her. No buyer will risk transferring 100 per cent to a new supplier but will test-purchase small quantities first.

4 Develop the most appropriate messaging and execute a highly targeted multi-channel marketing strategy (aim at all levels of a target).

5 Create engaging content to attract and nurture.

6 Connect with prospects where they spend their precious time.

7 Utilise telenurturing and telemarketing for lead follow-up and qualification.

8 Pass the lead to sales.

9 Close the loop, measure, refine and report to the senior management team.

BRIEF 3.12. Build a business community. Social media marketing is the activity of the moment – if it’s done right, it can deliver enduring benefits for your business, which translates into better, more sustainable returns for your shareholders.

• Engagement.

Interacting with your community members turns them into advocates.

• Loyalty.

Customers appreciate the opportunity to provide their ideas and suggestions.

• ROI.

A community with a defined strategy and clear goals can help your business reduce costs and increase sales opportunities, through FAQs, how-to videos and technical publications and by listening and responding to members’ conversations.

Case studies

Case study 5 – Relish Rewards by TLC Marketing for Pallas Foods

Pallas Foods is a leading foodservice provider in Ireland, with 9,000 customers in foodservice and a product range of 14,500+ products. Research showed that foodservice customers use seven suppliers on average, switching suppliers for price deals and promotional items. Rather than discount, Pallas Foods wanted a strong, self-funded loyalty programme to retain and reward customers and increase customer spend and basket size.

Relish Rewards target company owners, so Pallas is recognising and rewarding key decision makers, not those placing orders. Engaging artwork and witty copywriting juxtapose rewards with real Pallas Foods products, clearly communicating the offering and bringing it to life. The “Relish Rewards – A Little on the Side” programme smashed all target expectations. Rewards include weekends in Las Vegas, designer watches and even a Mini One.

Relish Rewards disrupted the Irish market by being the first and only B2B wholesale loyalty programme. Customers are now spending 15 per cent more than they used to and have increased basket items by 22 per cent, proving they have stopped using other suppliers and are now more loyal to Pallas Foods. The programme won an IPM 2017 Most Effective Incentive Gold Award

Case study 6 – B2B individual target promotion Be Brilliant! by S.A. for O2/Telefonika

The aim was not just to increase sales but also to improve the staff knowledge base. Be Brilliant! is an opt-in mobile optimised engagement portal. It drives and recognises desired behaviours to support O2’s vision. It is a dynamic platform for campaign activity (sale, learning, engagement) recognition. In a saturated market, Be Brilliant! has proven to be a key differentiator from the competition.

The company wanted to underscore its USP – individual digital advisors tasked with helping each client company to identify and then implement the latest mobile phone technology that would best help them deliver against their objectives. Digital Dave used an innovative approach – a holographic presenter in a box – combined with brilliant personalisation (50 versions of Dave were created to individually address IT heads at the 50 target companies) to create stand-out in the business mobile market. Dave spoke to the IT people by name and discussed their company’s needs. Getting them to complete online courses was a vital ingredient: they competed in 30 individual tactical campaigns, run across individual days or weekends, as well as manufacturer-sponsored 6–8 week promotions.

Promotion incentives included a trip to South Africa, a visit from Santa and ‘Christmas dinner in a box’ delivered to top stores (with over 5,000 Cadbury selection boxes distributed); 12 ‘Brilliant Days’ were awarded where stores were surprised by a ‘hit squad’ announcing that they had been recognised for being amazing and were taken away for a day out while the leadership team offered cover.

S.A. collected Telefónica no less than five awards for campaigns for its UK operations, which trade as O2, and was the IPM Brand Owner of 2016. What was particularly interesting was that the campaigns focused on B2B categories. The campaign so far has exceeded targets and delivered a return on investment of £13 for every £1 spent.

The importance of researching the customer is illustrated next.

Case study 7 – Listerine’s whiter-than-white mailing to dentists

Pfizer Consumer Healthcare (Agency RMG Connect) sent out a Listerine mailing directed at the highly sceptical dental profession that is regularly bombarded with ‘fact-heavy’ literature. Listerine prevents tartar build-up and helps keep teeth white. The visually striking letter spelling out these benefits was pure white and appeared to have no copy. Under a bright dentist’s light, it could be seen that the letter was printed in an embossed font. The letter had a fold-down reply-paid card enabling dentists to request samples and try the product for themselves. They would also be sent the offer of a subscription to a free trade magazine from which they could apply for further samples.

The mailing achieved a 14 per cent response rate against a target of 8 per cent. As many as 3,487 dentists ordered samples and subscribed to the quarterly magazine, exceeding target by 172 per cent. This success was attributed to the intriguing nature of the mailing piece, which won over a tough audience.

Case study 8 – Unilever Pot Noodle Spinning Fork

The Unilever promotion demonstrated a deep understanding of its target audience – the blokes snacking audience. The objective was to drive sales growth and it achieved year-on-year value growth over the promotional period of 11 per cent with a sales uplift of 20 per cent. The focus was on the funny side of man’s relationship with food and the need for a quick and easy taste hit. The promotion offered an on-pack instant win of a spinning fork together with a self-liquidating promotion for non-winners.

Case study 9 – Orchard Thieves launch by guns or knives for Heineken Ireland

In 2015, the cider market in Ireland was worth over €366 million; Bulmers controlled over 80 per cent of this. In 2015, Heineken Ireland launched Orchard Thieves to take on the cider market.

The campaign consisted of five activities: in pubs, ‘thieves’ asked people to ‘pick the pocket of fun’ to win prizes and sample pints. In-store consumers were asked to ‘thieve an apple’ to win prizes. Online signing up to ‘denofthieves’ is where games were played and free pint vouchers downloaded. On social media were posts teasing about a new product launch and around Dublin at night, with ambient ‘fox’ projections. The campaign story was ‘Be Bold’ (pursuing enjoyment, being alive, alert and spontaneous), delivering seeding of the brand and the brand idea, driving trial and awareness and finally achieving engagement.

Within 60 days of launching, 1.1 million drinks were taken (more than one third of the Irish adult population!) Awareness after 4 months was at 81 per cent and trial at 46 per cent, and market share rose to 6.6 per cent from zero. The campaign was a 2016 IMC Gold Award winner.

Case study 10 – Mazda’s Operation Renesis: Can you handle it?

Mazda’s insight into its target audience of professional 30–45-year-old males was paramount to the success of its Operation Renesis campaign. Potential customers were challenged to participate in a unique experiential event in which they would be trained to drive like a special agent. Applicants completed an online profiling questionnaire to establish their suitability. Taking cues from Spooks and The Bourne Supremacy, the three interactive driving zones included J-turns, avoidance driving and a proving ground complete with explosions and fog screens. The six most talented trainees won a training mission to Moscow.

The campaign delivered exceptional results, massively increasing the perception and awareness of the brand. It also generated significant PR through owners’ clubs websites, YouTube and Top Gear as well as creating an innovative property that can be leveraged in the future.

Case study 11 – Metropolitan Police target gun crime

Gun crime is a major issue in London’s black communities, with both offenders and victims becoming younger. In 2006, the Metropolitan Police, through Trident, a gun crime initiative, commissioned Roll Deep, a top Grime act, to produce an anti-gun music track, ‘Badman’. It was distributed without Trident branding to selected club DJs and music shops, as well as being e-mailed to Roll Deep fans. Six weeks later, the Trident involvement was revealed with the release of a branded video on its microsite, YouTube and RWD.com. It was also aired on channels KissTV and MTV (without payment). Further support came from a hard-hitting poster campaign and visits to London schools by Roll Deep.

Specific results are confidential, but the exposure and reach outperformed all expectations. This proved that the young, streetwise black audience is not unreachable, given the right approach.

Summary

Place the customer at the centre of your business. Start with the customer as shopper, identify your customer though Insight, think from the customer viewpoint. Make sure your Offer matches the customer’s need. Then build your preferred brandgram in his or her subconscious engram mind files, use the six-message media to achieve excess share of voice and assist the tipping point with a promotion at the point of sale to persuade and get the shopper to buy.

Future share value measurement. Call it ‘bonding with a brand’, that is, the customer has your brandgram in mind, which is entirely positive and exceeds any loyalty. It is a CEO deliverable – to have a brand that is wholly loved. It gives a value far in excess of the bricks-and-mortar worth of a company. The extent of bonding with a brand as a measurement can be used to predict future share value.

The most difficult element of a brand for any firm to manage is the ‘psychological’ part, that is, achieving and retaining ownership of a piece of the customer’s mind. Companies often talk about ‘creating an image’. They may do so in the minds of the staff who work long and hard to devise it. They only do so in customers’ minds when customers adapt, develop and absorb that image as their own, built as a mind file on the engram. Companies can offer an image, but they cannot make an image stick. If it is attractive and powerful and accords with customers’ own experiences, it will form part of their image of the product or service. Thoughts and images in our own minds are, thankfully, beyond anyone else’s total control.

Customers retain brandgrams, alongside the engram giving the brandgram a value; so if the brain senses an engram trigger then the full brand value is recalled as well as everything else in the brain’s subconscious. The engram is a ‘shorthand’ memory device like a computer desktop shortcut, a mix of logo, slogan or a feeling that the customer relates to ‘advantage’ with regard to a need. If you have such recall in a customer, you are made. But beware: if the concept you are selling does not match the perception, image and experience of the customer, you are far less likely to make a sale. You also need to nurture that retention constantly, and favourably reinforce it. Reducing brand support marketing in a recession is fraught with long-term risk. Guard against operational measures that destroy the brand’s value (think of banks after 2008! and, in 2014, Tesco and horse meat!).

It is quite possible to have different perceptions of your brand in different parts of the globe or even in different parts of one country.

BRIEF 3.13. Guinness, for a time, advertised in Africa, unwittingly using a symbol that implied that Guinness improved fertility. Brylcreem was thought to be a food delicacy in an African country. A failure of branding, you might think – unless of course you are happy to sell with that branding mismatch.

It is also quite possible to reposition a brand. Sometimes this is essential to save a brand that has become dusty and is failing. Failures are often the seedcorn of success if the lesson is understood.

BRIEF 3.14. Lucozade was originally an expensive drink for invalids. It was said that when a mother bought Lucozade for a child, you knew that child was really ill. In a Dublin bar, the marketing manager found that Lucozade was being used as a mixer. Realising there was no limit to what he could sell Lucozade as, he then had the idea of rebranding Lucozade as an energy drink for athletes – sales took off. Clearly anything innovative must have a potential market.

Self-study questions

1 To ensure you have understood, write a short sentence on each of the six Cs – the Offer – describing what needs of the customer each C covers. Then, as an exercise, write down the six Cs of your own business or organisation’s offer. From that, prepare a brand values statement – a brandgram: what you would want your customers to hold in their minds.

2 Why is understanding the customer first so important in business?