Chapter 14

Crisis on the Exchange

Why don’t you tell them what to do, Mr. Morgan?

—Belle da Costa Greene, J. P. Morgan’s personal librarian

I don’t know what to do myself, but sometime, someone will come in with a plan that I know will work; and then I will tell them what to do.

—J. Pierpont Morgan1

As Oakleigh Thorne was opening the doors to the Trust Company of America on Thursday morning, October 24, J. Pierpont Morgan boarded a Union Club brougham drawn by a white horse, which would take him to his offices at 23 Wall Street.2 By this time people throughout the city had already seen Morgan’s picture on the front pages of many newspapers, which had proclaimed him the city’s savior. Herbert Satterlee, Morgan’s son‐in‐law, was traveling in the brougham with Pierpont, and he provided a vivid description of the atmosphere surrounding the titan that morning:

All the way downtown people who got a glimpse of him in the cab called the attention of passersby. Policemen and cabbies who knew him well by sight shouted, “There goes the Old Man!” or “There goes the Big Chief!” and the people who heard them understood to whom they referred and ran beside the cab to get a peep at him. Near Trinity Church a way through the crowd opened as soon as it was realized who was in the cab. The crowd moved with us. He might have been a general at the head of a column going to the relief of a beleaguered city such was the enthusiasm he created. All this time he looked straight ahead and gave no sign of noticing the excitement, but it was evident that he was pleased.3

People filled the streets at the corner of Wall and Broad in lower Manhattan. As Morgan descended from the carriage and hurried up the steps of J. P. Morgan & Company, the mob first became quiet, and then they fought their way forward to peer at the man through the windows. When he arrived inside, his office was thronged with men desperate to borrow money. Morgan went directly to his private office, where he began a conference with George Baker, James Stillman, and several other bank and trust company officials.

The Federal Government Lends Assistance

While Morgan conferred with his colleagues, dozens of vehicles were parking outside the Federal Subtreasury building across Wall Street. After a late‐night meeting with Morgan’s partner, George Perkins, Treasury Secretary George B. Cortelyou announced his formal support for the crisis team, committing $25 million in liquidity to quell the crisis. In an official statement given to reporters at 12:30 a.m. on October 24, Cortelyou asserted,

Wherever there is weakness, and it has been in but a comparatively few instances, strong and able men are rendering aid; and in behalf of the Treasury Department I may say that I believe it my duty to do, and I shall do, in the largest way possible, whatever may be necessary to afford relief.4

This was a precedent‐setting statement, close to a “do whatever it takes”a commitment to deal with the crisis. In another comment to a reporter, Cortelyou said, “Not only has the stability of the business institutions impressed me deeply but also the highest courage and the splendid devotion to the public interest of many men prominent in the business life of this city.”5

Strictly speaking, the federal government support would not go to Morgan, but to nationally chartered banks in New Yorkb—and eventually elsewhere. Cortelyou expected the national banks to redirect these funds to places of greatest need. This made sense, since the national banks were closer to the condition of the financial system than were public officials in Washington, DC. The national banks were the best‐monitored and generally the soundest part of the U.S. financial system. Therefore, the risk of loss to taxpayers might be lower than if the government loaned directly to distressed financial institutions. By placing the national banks in between the government and the sources of instability, the government relied on the national banks to act as shock absorbers in the event of loss. And the support to national banks would take the form of deposits or collateralized loans, not capital investments or gifts—this was an injection of liquidity, not a resolution of insolvency.

Cortelyou’s announcement of federal government support on October 24 is significant: it was the first instance of a general federal intervention in a financial crisis.6 However, Cortelyou’s predecessor, Leslie Shaw, had begun a policy of liquidity management by shifting Treasury gold reserves into and out of national banks to alleviate credit needs associated with the ordinary agricultural cycle. Cortelyou’s innovation was to apply Shaw’s policy more aggressively during a banking panic.

Thus, from the end of September to October 31, Cortelyou had shifted about $54 million into national banks to quell the crisis. By the end of November, he would shift another 10 million into the national banks.7 But by then, the balance of discretionary currency within the U.S. Treasury Department had fallen to $5 million, effectively sidelining Cortelyou as a crisis fighter.c Nevertheless, his active deployment of currency into national banks rendered Cortelyou a power player on par with J.P. Morgan.

Throughout the morning of Thursday, October 24, men carried bags and boxes of gold currency and greenbacks from the federal vaults at the New York Subtreasury to the various banks approved by Cortelyou. Meanwhile, John D. Rockefeller Sr. also called on Morgan to assure him of his willingness to help. Rockefeller deposited $10 million with the Union Trust Company, and promised additional deposits of $40 million, if needed.8

A Crisis in Call Money

The panic, however, had already spread further. Owing to the stricken trust companies that frantically demanded repayment of collateralized loans, an acute shortage of money had occurred on the New York Stock Exchange. Brokers were intensely anxious. And the credit crunch, accelerated by the events in October 1907, worsened the anxieties.

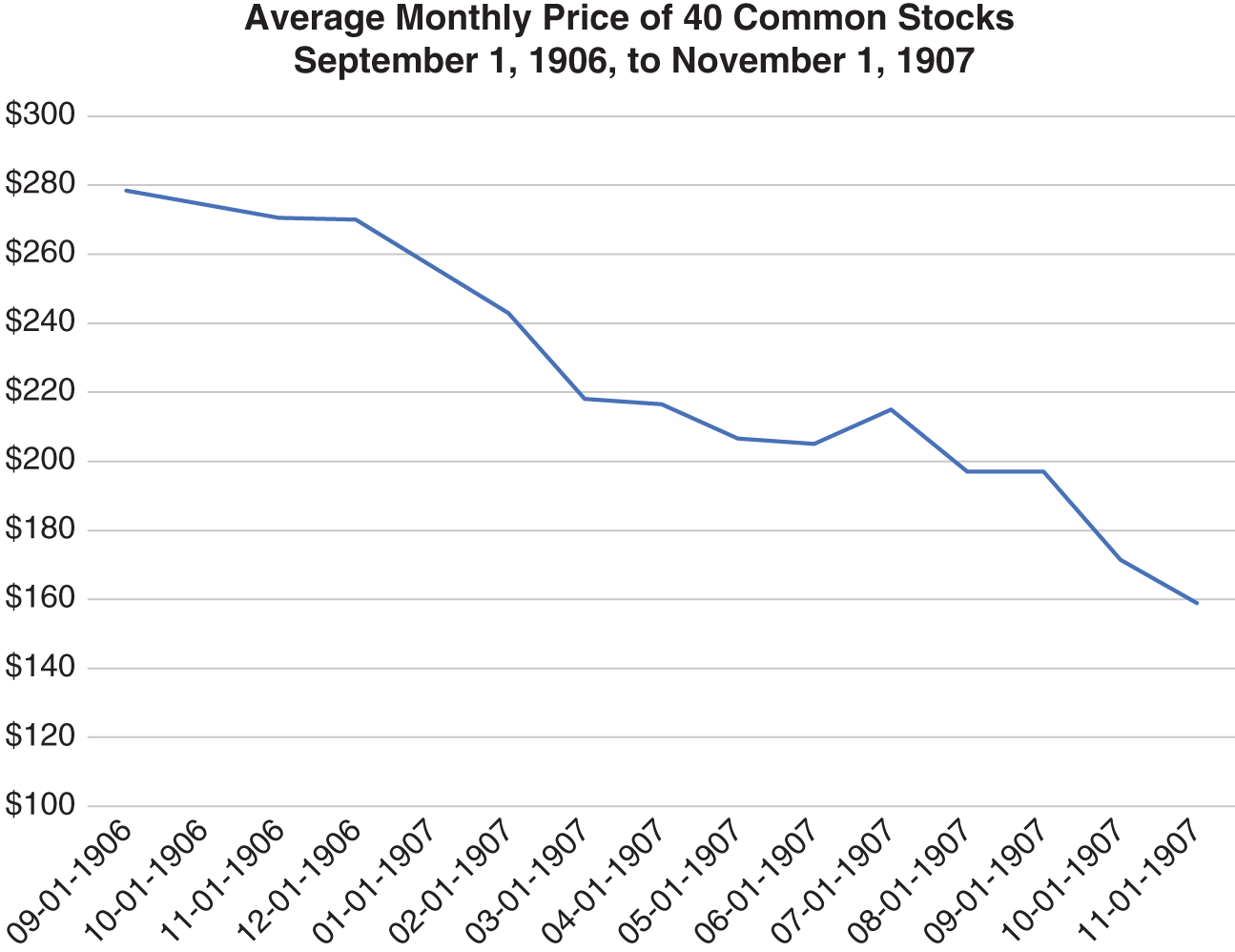

Figure 14.1 shows that the stock index had plunged 43 percent from September 1906 to November 1907. In October alone, it fell 7.3 percent. In the 132 months since 1896, only seven months had featured stock market declines of that size or greater—and four of them had occurred in 1907. Amid such declines, only short‐sellers would be happy—and even they grew fearful as margin loans suddenly grew more costly and harder to find.

At 10 a.m. on October 24, the interest rate on call money at the Exchange opened at 50 percent. Yet sometime later in the morning a bid was made for 60 percent and no money was offered. By 1 p.m., call money was being loaned at the extreme rate of 100 percent.9 “It was evident that difficulty was being caused by the calling of loans by a good many trust companies which, alarmed by the run that already had taken place on three companies [Knickerbocker Trust Company, Trust Company of America, and Lincoln Trust Company] were hurrying to strengthen their own cash position,” George Perkins observed.10 An already tight money market was now further strained by the trust companies pulling their cash out of the market. With money so scarce, prices on the Exchange were headed into a tailspin.

Figure 14.1 Stock Price Average, September 1906 to November 1907

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from National Bureau of Economic Research, Average Prices of 40 Common Stocks for United States [M11006USM315NNBR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M11006USM315NNBR, April 30, 2022.

Call money financed the positions of stock market brokers, dealers, and speculators—all of whom helped to ensure liquidity in trading, the ability to find a counterparty whether one was buying or selling. This market was highly consequential for the banking industry: it became an attractive investment for excess liquid resources. Mary Tone Rodgers and James Payne note that “In the period leading up to the 1907 crisis, about half of all bank loans in the United States were secured by stocks in the call loan market.”11 Jon Moen and Ellis Tallman highlighted the significance of the call loan market, a business that national banks dominated and that trust companies aggressively entered after 1897, 12 in the rise of the trust companies and the dynamics of the Panic of 1907. Call loans outstanding in New York City varied from $400 million to $600 million per day.13 Moen and Tallman wrote, “It was well known that national banks in New York invested their bankers’ balances (deposits from other banks used to maintain correspondent relationships and to meet reserve requirements established under the National Banking Acts) in the call loan market at the stock exchange. But other intermediary types loaned out funds on the call loan market as well. Collateralized loans, a grouping that includes call loans, comprised over 85 percent of New York trust loans in 1907.”14 Moen and Tallman argued that trust companies free rode on an “implicit insurance contract”15 from the NYCH banks to “alleviate the extreme liquidity demands arising from either the capital market or the payment system/money market. These actions were intended to forestall any large‐scale liquidation of call loans (and potentially, of the stock collateral supporting the loans).”16

Interest rates on call money typically varied in the single digits since lenders saw these well‐collateralized short‐term loans as very liquid and low risk. However, call money interest rates periodically spiked, reflecting crises and adverse economic conditions.

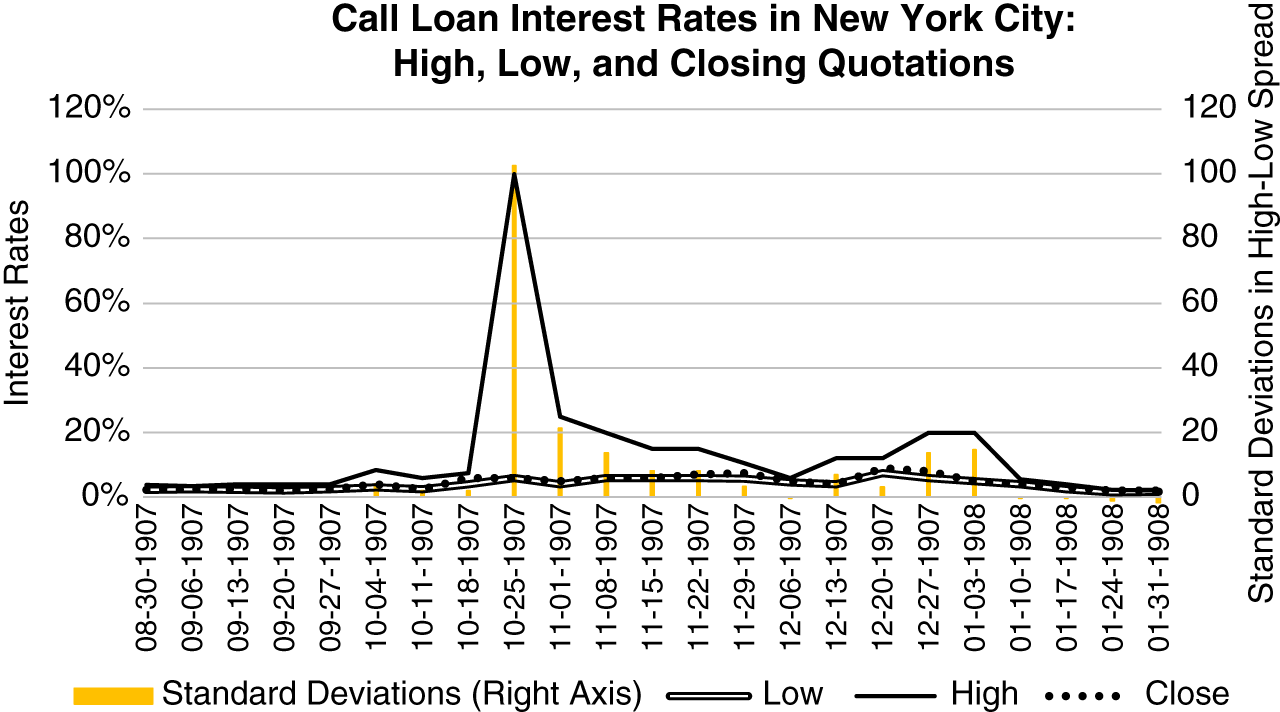

Figure 14.2 presents the daily call money rates recorded during the Panic of 1907. Rates surged shortly after the failure of the corner on United Copper and did not return to single digits until the end of the year. The spike to 100 percent in call loan interest rates on October 24 suggests the extremity of capital market conditions and generally the threat to financial system stability. The figure also presents the spread between high and low call money interest rate quotations as measured by the number of standard deviations from average spreads17—the size of such spreads measure market dysfunction and risk. The standard deviations indicate the chance that the high–low spreads are just due to trading “noise.” Of the 86 days depicted in the figure, 47 of them show standard deviations of 3.0 or more—indicating a very low probability (4 in 1,000) that these extreme high–low spreads were just random variations. Conditions in the call loan market during this period suggested great turmoil and uncertainty.

Rising interest rates on call money on October 24 reflected declining supply. Depositor runs on financial institutions (particularly trust companies) triggered liquidation of loan portfolios. Demand loans (“call loans”) were the easiest to liquidate. Under normal conditions, a speculator might meet a call for payment by borrowing from another institution. However, on October 24, finding the funding to “roll over” the loan suddenly proved difficult. In the absence of refinancing, the speculator would have to sell the stocks, possibly taking a loss. Falling stock prices would trigger more collateral calls and stock sales. A self‐reinforcing doom loop of liquidation would begin. The impact of many investors throwing their shares on the market would have one outcome: a stock market crash.

Figure 14.2 Daily Call Loan Interest Rates, August 1907 to January 1908

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on hand‐collected quotations in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, September 1, 1907, to January 30, 1908.

Panic on the New York Stock Exchange

Around 1:30 p.m. on October 24, Ransom H. Thomas, the president of New York’s Stock Exchange, and one of his assistants came over to the Corner in a state of great excitement. When he arrived, the offices of J. P. Morgan & Company were full of other agitated men, but Thomas rushed up to the financier and said, “Mr. Morgan, we will have to close the Stock Exchange.” Morgan turned to him and asked sharply, “What?” Thomas repeated, “We will have to close the Stock Exchange.” Morgan asked, “At what time do you usually close it?” Thomas answered, “Why, at three o’clock.” Morgan thundered, “It must not close one minute before that hour today!” emphasizing each word by keeping time with his right hand, middle finger pointing directly at the president of the Exchange.18 Under the circumstances, closing the exchange early would signal a breakdown in the Exchange’s market‐making function and would inflame fears about financial system stability, accelerating the calling‐in of brokers’ loans, the fire sales of assets, the failure of brokerage firms, and the downward spiral of stock prices.

Thomas then explained that unless a significant amount of money was offered on the stock exchange in a very short time, many failures would result. Morgan said he would take immediate steps to arrange a loan, and he sent Thomas back to the Exchange. The situation only seemed to get more desperate with each passing moment. “One broker after another came into our office, begging us to do something—many with tears in their eyes and others almost weak with the shock of being suddenly faced with failure,” George Perkins recalled. “They had the securities on which to raise money but there was no money to be had.”19 Finally, at about 1:45, Morgan asked that the presidents of the banks (not the trust companies, this time) be called to his office immediately. The city’s bankers started to arrive around 2 p.m.; the moment the brokers on the Exchange feared most would be in 20 minutes, when the Exchange customarily compared all the day’s sales and adjusted brokers’ accounts. This would be literally a moment of reckoning.

When the bank presidents had finally gathered at the Corner, Morgan explained the situation to them. He said simply that unless they raised $25 million within the next 10 to 12 minutes, at least 50 Stock Exchange houses would fail. James Stillman, president of the National City Bank, promptly offered $5 million; the other bankers quickly fell in line. By 2:16 p.m., Morgan had secured $23.6 million from 14 banks. He ordered that these funds should be loaned at 10 percent,20 a rate dramatically below the interest rates currently quoted at the Exchange, to quell fears of a credit crunch. Within minutes, word of the new “money pool” buoyed the Street, as Perkins later observed:

Our outer office at this moment was filled with brokers awaiting the result of the conference. The bank presidents hurried out of our private offices into these outer offices and someone must have exclaimed that a $25 million fund had been raised because, as I hurried from the office to start the machinery of loaning in motion, I saw some man’s hat sail towards the ceiling as he shouted, “We are saved, we are saved!”21

When the money hit the market at 2:30 p.m., men clambered over one another to get to the Exchange’s “money post” seeking a loan; in the mayhem, even one of Morgan’s associates had his coat and waistcoat torn off. The New York Times reported that money brokers scrambled wildly for the funds as fast as borrowers’ names could be written down, adding that for the first time in 10 days the mood on the trading floor was cheerful. At 3:00 p.m. when the Stock Exchange closed, there was “a mighty roar of voices” that could be heard from the floor of the Exchange. The members had joined in yelling, “What’s the matter with Morgan? He’s all right!” followed by three cheers.22 Of the total raised for the money pool by Morgan on Thursday afternoon, nearly $19 million was loaned out in 30 minutes at interest rates ranging from 10 to 60 percent.d After the market close, scores of men crowded in front of J. P. Morgan & Company carrying boxes of collateral to secure their share of the pool.

Around 7 p.m. Morgan and Perkins finally left their offices to head uptown. As they started to leave the building, the normally reticent Morgan approached a throng of reporters. Straightening up and squaring his shoulders, he said slowly and earnestly, “If people will keep their money in the banks, everything will be all right.”23 Then he quickly turned, went out the door, and drove uptown.

Distress Spreads through More Financial Institutions

J. P. Morgan’s efforts had kept the Stock Exchange open on Thursday, October 24, but his victory there had not been decisive. The Twelfth Ward Bank and Empire City Savings Bank suspended in the afternoon. The Hamilton Bank of New York ceased operations, and many more institutions closed in rapid succession: First National Bank of Brooklyn, International Trust Company of New York, Williamsburg Trust Company of Brooklyn, Borough Bank of Brooklyn, and Jenkins Trust Company of Brooklyn. By Friday morning, the Union Trust Company of Providence, Rhode Island, failed to open as well. Most worrisome of all, runs continued unabated at the beleaguered Trust Company of America and the Lincoln Trust.

Early in the morning on Friday, October 25, George Perkins made successive visits to Cortelyou, Stillman, Baker, and Morgan, securing their agreement once again to save the Trust Company and the Lincoln Trust. At Morgan’s library after breakfast, they finally decided to place more funds at the disposal of the two firms, and, if necessary, to consider taking up another money pool in the afternoon. In the meantime, Perkins met hurriedly with Lincoln Trust and Trust Company of America officials. He strongly urged them to open for business on time, even suggesting that they resort to paying depositors as slowly as possible, and by artifice if necessary. “It was not because we were particularly in love with these two trust companies that we wanted to keep them open,” Perkins later explained. “Indeed, we hadn’t any use for their management and knew that they ought to be closed, but we fought to keep them open in order not to have runs on other concerns and have another outburst of panic and alarm.”24

Crisis Returns to the New York Stock Exchange

At 10 a.m. on Friday, October 25, trading on the stock exchange began as usual, but “with the air charged in every direction with panic.”25 Prices quickly began to collapse, and rumors abounded that one brokerage or another was in peril. “At all times during the day there were frantic men and women in our offices,” Perkins recollected, “in every way giving evidence of the tremendous strain they were under.”26 Again the panic‐stricken trust companies were calling in their loans, which caused an acute shortage of money. By midday, call loan interest rates reached 75 percent.27 Morgan and his associates pleaded with the trusts to extend their loans and implored the president of the Exchange to cease all buying or selling on margin. However, their efforts could not outpace the speed with which the trust companies were pulling their cash out of the market. By 1:30 p.m., the market was in exactly the position it had been in the day before, with no money available and numerous firms on the brink of failure.

Finally, Ransom Thomas, president of the Exchange, went to see J. P. Morgan personally, asking him to call another meeting of the 14 major bank presidents. Morgan agreed, but he decided he should go in person to meet with them at the offices of the NYCH itself, where he would ask them to raise another pool of $15 million. When he did so this time, the banks were less willing to be so generous, and they agreed only to provide $9.7 million. That would have to do. Morgan insisted that these funds carry restrictions: No margin sales were allowed (only cash could be used for investments), and the full amount of the pool would not be released until the afternoon.

Following the meeting at the NYCH, J. P. Morgan, clearly at the height of his power, marched on foot to his own offices at the Corner. Herbert Satterlee, Morgan’s son‐in‐law, provided a description of him at that very moment, which has become among the most vivid and enduring images of the man:

Anyone who saw Mr. Morgan going from the Clearing House back to his office that day will never forget the picture. With his coat unbuttoned and flying open, a piece of white paper clutched tightly in his right hand, he walked fast down Nassau Street. His flat‐topped black derby hat was set firmly down on his head. Between his teeth he held a cigar holder in which was one of his long cigars, half smoked. His eyes were fixed straight ahead. He swung his arms as he walked and took no notice of anyone. He did not seem to see the throngs in the street, so intent was his mind on the thing that he was doing. Everyone knew him, and people made way for him, except some who were equally intent on their own affairs; and these he brushed aside. The thing that made his progress different from that of all the other people on the street was that he did not dodge, or walk in and out, or halt or slacken his pace. He simply barged along, as if he had been the only man going down the Nassau Street hill past the Subtreasury. He was the embodiment of power and purpose. Not more than two minutes after he disappeared into his office, the cheering on the floor of the Stock Exchange could be heard out in Broad Street.28

The second money pool was loaned out at once on the Exchange, at rates ranging from 25 to 50 percent, and it proved sufficient to meet all demands: No brokerage failures were reported, and again the Exchange stayed open until 3 p.m. By the time of the market’s close, $6 million of the new pool had been loaned out on the Exchange; the rest was offered after hours to discourage speculation. Overall trading volume was down to 637,000 shares from one million the day before. By the end of this day, however, seven more banks still had failed. To protect themselves from running out of cash, the presidents of the New York savings banks imposed a rarely invoked requirement that depositors must give a 60‐day notice for any withdrawals.

Morgan’s successive rescues of the NYSE engendered other criticisms, offered later. Some said that he was bailing out his cronies. Others asserted that he used taxpayer money to sustain speculative activity in the stock market. Still more said that the money would have been better applied to the needs of banks in the interior of the country. Finally, some said it was driven by greed; after all, Morgan earned interest on his loans to the NYSE.

There was a grain of truth in each of these criticisms. However, they ignored the fact that in 1907, the stability of the U.S. financial system perched precariously on the stability of the NYSE. Banks in the interior had sent their surplus reserves to trust companies in New York, to earn higher rates of interest than elsewhere. The trust companies had invested those funds in call loans to earn high interest rates during the credit crunch. Call loans fueled the stock market. A sustained absence of call money on the NYSE (as on October 24, 1907) would trigger debtor defaults and fire sales of stocks. Defaults and falling asset prices would destabilize trust companies, prompting runs, suspensions, and insolvencies. The Panic would worsen and lengthen. In short, Morgan saved the NYSE to stanch the financial panic and set the stage for recovery.

Appealing to the Public

At the library on Friday evening October 25, Morgan and his associates acknowledged that rescuing financial institutions had not achieved their chief aim of restoring public confidence and ending mass withdrawals of deposits. They turned their attention toward directly reassuring the public. They formed two committees. One was responsible for disseminating all information about the financial rescue efforts to the press; all inquiries would be directed here, and any attempts at evasion or secrecy were to be avoided. The second committee would reach out directly to the clergy, encouraging them to make reassuring statements to their congregations over the weekend. “We arranged so far as we could that sermons should be preached in the various churches on Sunday,” Perkins said, “cautioning people to act calmly and not to withdraw the money and lock it up.”29 According to Satterlee, a member of this committee then visited every possible clergyman, priest, or rabbi in New York on Friday or Saturday. Having won the day’s battles, Morgan finished his day with a game of solitaire in the library and then went to bed around 2 a.m.

Notes

- a. Such a phrase is familiar in the twenty‐first century as a turning point in a financial crisis. On July 26, 2012, in the depths of the Global Financial Crisis, Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, said that “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro.” Similarly, in his understated way Jerome Powell, chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, expressed a similar message at the nadir of the financial crisis in March 2020.

- b. J.P. Morgan & Co. was a private bank (it did not accept deposits from the public or issue banknotes), did not hold a national bank charter, and was not a member of the clearing house. As such, the firm would not qualify as a recipient of U.S. Treasury deposits. Nonetheless, through his business connections and the respect he commanded, Pierpont had some influence with leaders of the NYCH and the large national banks. For instance, researchers Tallman and Moen (1990, p. 9) wrote, “… nearly all the funds contributed to aid the panic were controlled by J.P. Morgan who decided how much money to use and where.” How much this influence translated into direction over distribution of the federal government deposits remains a subject for further research. Certainly, as Morgan’s efforts to mobilize collective action among the trust companies reveals, even his powers were limited.

- c. In late November Cortelyou would employ another strategy of issuing government bonds that banks could use as reserves upon which to issue banknotes. For more detail on Cortelyou’s monetary management, see Chapter 23.

- d. R. Glenn Donaldson (1992) analyzed the trend of call money interest rates in comparison to a rate predicted by a model and concluded that Morgan and his circle colluded to keep interest rates exorbitantly high—consistent with the conclusions of the Pujo Committee (1912–1913) about the existence of a money trust. The facts, as reported by mainstream press, refute Donaldson’s inference. Morgan directed that the offered rate on his rescue funds should be 10 percent. A possible explanation for interest rates higher than Morgan’s 10 percent target would be that the higher rates were asked by lenders not belonging to Morgan’s pool. Or perhaps the pool lent funds to other intermediaries, who charged the higher rates.

- 1. Recounted in Satterlee (1939), p. 477. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 2. Ibid., p. 473. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 3. Ibid. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 4. Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33 (January 1908), p. 227.

- 5. Quoted in the New York Times, October 25, 1907, p. 7.

- 6. In 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton deployed the resources of a bond sinking fund to stabilize the stock market in shares of the Bank of the United States after a corner attempt. Even that was a targeted intervention in one security. Cortelyou’s intervention was the first general injection of liquidity into credit markets in U.S. history.

- 7. The estimates of $54 million and $64 million are derived from data in Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33 (January 1908), pp. 37–72.

- 8. An audit in 1902 showed that John D. Rockefeller Sr. was worth about $200 million; by comparison, at the time of his death in 1913, J. P. Morgan’s estate was valued at approximately $80 million.

- 9. “Call Money Loans at 100%,” Wall Street Journal, October 25, 1907, p. 8.

- 10. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.

- 11. Rodgers and Payne (2014), p. 420.

- 12. Moen and Tallman (2003), pp. 10, 12.

- 13. Moen and Tallman (1992), p. 625.

- 14. Moen and Tallman (2000), p. 149.

- 15. Moen and Tallman (2014), p. 1.

- 16. Moen and Tallman (2003), p. 2.

- 17. The number of standard deviations is equivalent to a “Z‐score,” computed as (Xt – χ)/σ, where Xt is the observed high–low spread for day t, χ is the average spread between daily high and low call money rate quotations from August 29 to September 29, 1907, and σ is the standard deviation of high–low spreads from August 29 to September 29. Over the hold‐out period, χ was 1.76 percent and σ was 0.90 percent. Data were obtained from hand‐collected quotations in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times.

- 18. Satterlee (1939), p. 474. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 19. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.

- 20. “Money: Loaning Power of Banks Reduced by Extending Aid to Others,” Wall Street Journal, October 26, 1907, p. 1.

- 21. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. Satterlee (1939), p. 476. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 24. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. “Call Money Rates,” Wall Street Journal, October 26, 1907, p. 8.

- 28. Satterlee (1939), p. 479. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from J. Pierpont Morgan: An Intimate Portrait by Herbert L. Satterlee. Copyright © 1939 by Herbert L. Satterlee; copyright renewed, © 1967 by Mabel Satterlee Ingalls. All rights reserved.

- 29. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.