Chapter 21

Money Trust

In 1873, … [t]he Money Trust began forming soon after the [Civil War] to control the volume and issue of money, the same as Industrial Trusts have since sought to control the products in which they deal… . This organization is the principal ally of the political party that champions the interests of the privileged classes… . What is the outcome if class legislation and Trusts continue unchecked? … The Financial Trust will own all the other Trusts.

—William H. “Coin” Harvey, 18991

Conspiracy theories of a moneyed elite taking over American society had sprouted episodically since the founding of the Republic. In the 1890s, the populist reaction to growing industrial concentration and financial crises spawned the notion of a “money trust.” Books and articles by William Harvey (under the pen name “Coin”) promoted the idea. But it circulated mainly among activists until the Panic of 1907, after which it entered the political mainstream.

On March 17, 1908, Senator Robert La Follette resurrected the money trust idea to claim that the Aldrich–Vreeland Act was a sop to some 100 financial leaders, a “comparatively small clique, which has succeeded in dominating the finances of the country.” Furthermore, La Follette argued that this group plotted the Panic of 1907, “to satisfy business, legislative and political grudges, and to advance their own selfish interests.” He said, “Morgan was especially wroth with Morse, while Standard Oil had long awaited opportunity to wipe off old scores with Heinze.” He named groups of banks associated with Standard Oil and J.P. Morgan which controlled the “financial interests of the country” through their membership on boards of directors. Finally, La Follette claimed that the Panic rescues were “done with due regard to stage effect and only when the spotlight was turned upon the Morgan‐Standard Oil combination.” He denounced those who termed either Morgan or the Standard Oil group “philanthropists or unselfish financiers.”2

A Tendency Toward Consolidation

Activities of J. P. Morgan and New York financiers after 1907 strengthened allegations about a money trust. In December 1909, Morgan acquired control of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, one of the major insurance companies—and his firm held seats on the board of another leading insurer, New York Life, while Mutual Life (the third large New York insurance company) was controlled by Rockefeller associates.3 The Washington Post worried that the takeover marked “a complete reversal of the old order under which the insurance companies controlled the destinies of the banks and trust companies.”4

J. P. Morgan Jr. joined the board of National City Bank. In late 1909, Pierpont also engineered the merger of three New York trust companies—Morton, Fifth Avenue, and Guaranty—to produce a firm with $200 million in assets.5 The Chicago Daily Tribune decried the “almost absolute control of the country’s financial affairs … centralized in the hands of a few men who are acting in concert.”6

Morgan’s purchase of the Equitable brought with it control of the National Bank of Commerce,7 the firm that had declined to clear for the Knickerbocker on October 20, 1907. Bank of Commerce had been a material player in the New York financial community and historically had been related to Morgan. But since at least 1907 it had not been so close to Morgan or the Rockefeller interests. Fearing that the bank would create other episodes of instability in the financial system, Morgan began acquiring more of the bank’s shares.8 In March 1911, a syndicate of J.P. Morgan & Company, City National Bank, and First National Bank gained complete control of the board.9

In all, by March 1911, the Washington Post observed that “there are only two‐thirds as many national banks and large state banks in downtown New York as there were 20 years ago.”10 In hindsight, the Morgan‐led consolidation wave in New York seems remarkably tone‐deaf to the mounting public fears of a money trust.

Money Trust Investigation

On July 8, 1911, Representative Charles A. Lindbergh Sr., a progressive Republican from Minnesota (and father of the future famous aviator), declared that a “money trust” existed. Biographer Scott Berg described “Sr.” as a distant father, poor businessman, and a progressive driven by strong principles.11 He was in his third term as a representative. Lindbergh called for a Congressional investigation “to determine if there exists a combination of financiers in the United States operating in restraint of trade or violation of other laws.”12 Then and in other speeches that year he argued that the Aldrich–Vreeland bill would lead to another panic and “that the methods of the Money Trust, more than any other thing, are directly and indirectly responsible for the cost of living being several times higher than it should be.”13 Lindbergh’s charge harnessed public ire about industrial trusts and shifted the spotlight onto the financial sector of the economy.

This was a logical consequence of the Panic of 1907. The lurid revelations about U.S. Steel’s takeover of TC&I, reports of investor pools to manipulate stock prices, the Heinze–Morse ring, and the commanding ability of J. P. Morgan to marshal rescue funds were catnip to conspiracy theorists. By December, the Democratic majority in the House chartered an investigation by a subcommittee of the House Committee on Banking and Currency to be led by Arsène Pujo, a representative from Louisiana. The next month, the subcommittee hired Samuel J. Untermyer, a politically ambitious lawyer from New York, to serve as chief counsel. The committee began hearings on June 7, 1912 and concluded on January 15, 1913.

Before the hearings began, Untermyer had declared his belief in the existence of a money trust;14 so did the House resolution that chartered the investigation:

… it has been charged, and there is reason to believe, that the management of the finances of many of the great industrial and railroad corporations of the country … is rapidly concentrating in the hands of a few groups of financiers … and that these groups by reason of their control over the funds of such corporations and the power to dictate the depositories of such funds, and by reason of their relations with the great life insurance companies … have secured domination over many of the leading national banks and other moneyed institutions … thus enabling them and their associates to direct the operations of the latter in the use of the money belong to their depositors.…15

The hearings aimed to prove a belief by gathering targeted evidence, rather than to gather diverse evidence and form a belief. Launched shortly before the federal elections in November 1912, the hearings served to propel progressives toward the Democratic Party. Modern historians judged the hearings to be “extremely partial … exaggerated”16 and consistent with a “paranoid style” in American politics that suspected a vast conspiracy to destroy American life.17

Called to Testify

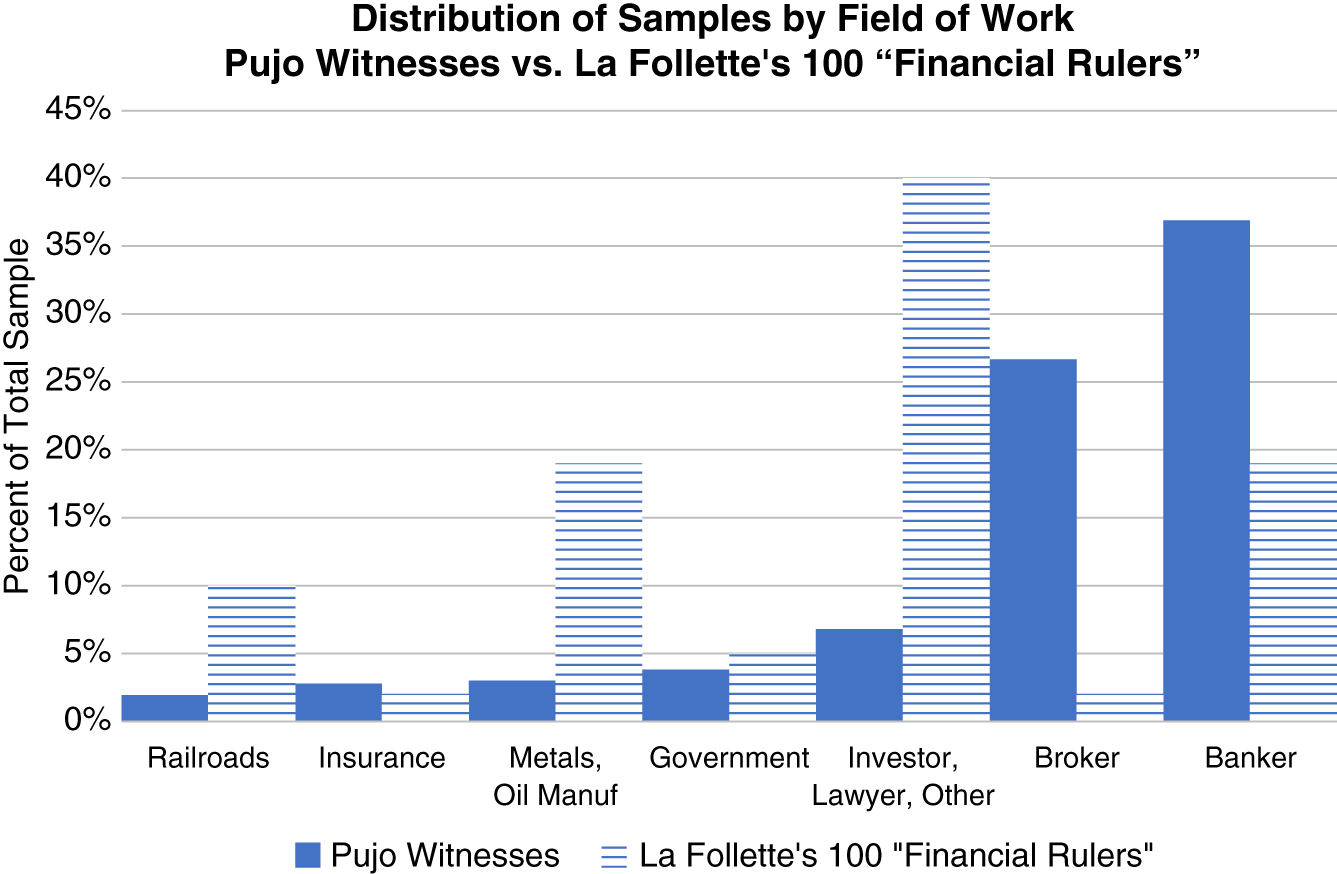

The 2,198 pages of the subcommittee’s report are a monument to prosecutorial investigation. Altogether 90 people testified at the money trust hearings. A few others were invited but declined due to ill healtha or absence from the country. Was this a representative sample of the “financial rulers” that Senator Robert La Follette had charged in 1908 controlled the business of the nation?

Figure 21.1 Percent of Total Hearings Accounted for by Witnesses from Various Fields

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, prepared from data in “Financial Rulers Names by Senator La Follette,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1908, p. 4, and “Money Trust Investigation,” U.S. Government Printing Office, 1913.

Analysis of the hearings shows that testimony from bankers and brokers accounted for almost two‐thirds of the proceedings.b In comparison, La Follette’s rogue’s gallery was a more diverse lot, dominated by business executives and investors who inherited their wealth. Figure 21.1 compares the distribution of time under oath by witnesses in various fields to the distribution of La Follette’s 100. The comparison suggests that the Pujo hearings were plowing different ground: more focus on the financial sector, less focus on the cross‐section of business.

Only seven of the Money Trust witnesses had also appeared on La Follette’s list of 100 “financial rulers.” They were George F. Baker (First National Bank, who accounted for 11 percent of the total time under oath), James J. Hill (Great Northern Railroad and director in banks, 0.6 percent), J. P. Morgan (6.7 percent), George W. Perkins (1.7 percent) Jacob Schiff (Kuhn, Loeb, 2.6 percent), Charles Steele (J. P. Morgan & Co., 0.2 percent), and Frank K. Sturgis (Strong, Sturgis & Co, NYSE, 3 percent)—these seven amounted to about a quarter of the accumulated testimony. The difference between the lists of La Follette and Pujo reveals a crucial point: the investigations were heavily focused on finance, not industry, and on Wall Street, not Main Street. Untermyer further sharpened the focus on Wall Street by inviting testimony from a few locales outside New York (such as Salt Lake City, Pittsburgh, and Boston). And even within the New York City financial community, Untermyer sought to distinguish the experience of trust companies and small banks apart from the members of the New York Clearing House.

The Proceedings

Untermyer was a tough interrogator: interrupting, asking leading questions, and in some cases badgering witnesses. Much of the testimony was banal, a recitation or confirmation of facts, some of which were widely known. And the thread of questioning frequently meandered into ancillary details raised by the witnesses. On occasion, the witnesses caught Untermyer off guard. He seemed to be playing to a jury of public opinion rather than the 11 representatives on the subcommittee. Much of the minutiae about business practices had little to no bearing on the conclusions the committee reached.

Yet it was not a fishing expedition. The investigator’s questions revolved around a few themes: the control of corporate governance through interlocking directorships; control of securities underwriting by large New York firms; the power of the New York Clearing House; the concentration of bank reserves in the New York call money market; the exclusionary structure of underwriting syndicates, and so on. The breadth of these issues would eventually be knitted into an allegation of control of finance by a circle of individuals and firms located on Wall Street.

Untermyer’s investigatory style was illustrated in his handling of the star witness, J. P. Morgan, who appeared on December 18–19, 1912. By then, Morgan was in his 75th year and in semi‐retirement from his firm—he was suffering from a long illness and would die three months later.18 Even‐tempered and highly respectful of Untermyer, Morgan frequently asked his questioner to repeat a statement and was unable to recall details about his dealings, although he regularly offered to have the questions researched and answered later. Spectators did not expect what proved to be an assertive defense of the financial sector, Morgan’s firm, and himself—this was Morgan’s last hurrah.

The highlight of Morgan’s testimony occurred when Untermyer sought to prove that banks only extended credit to wealthy persons. Untermyer asked whether Morgan would lend money to someone who had none.

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Mr. Untermyer:

Mr. Morgan:

Biographer Jean Strouse summed up Morgan’s testimony: “He was as certain that he had been doing the country great service all his life as Untermyer was certain that the Money Trust was up to no good, and the gulf between their positions came out plainly on the subject of monopoly concentration. What to Untermyer represented an oligarchical “system, vicious and dangerous beyond conception” had for Morgan evolved as a practical solution to a range of economic problems.”20

The Findings

The report of the subcommittee made three claims. First, the existence of underwriting syndicates of the same firms proved a high degree of coordination and alignment in the actions of a few banking firms. The report alleged that an inner group of three firms (J. P. Morgan & Co., National City Bank, and First National Bank) influenced seven other large institutions (Bankers Trust Co., Guaranty Trust Co., Astor Trust Co., National Bank of Commerce, Liberty National Bank, Chase National Bank, Farmers Loan & Trust Co.) to wield about $1.6 billion in resources.21 In absolute terms, this was a material but not overwhelming portion of the nation’s financial resources, equivalent for instance to about 10 percent of the U.S. money supply in 1913.22

Second, the hearings asserted that the money trust occupied an important position in bringing corporate securities to market, that it was the gatekeeper to the public capital markets. The source of its power was “other people’s money,” the access to cash that could be deployed into stock and bond offerings—or, into funding of the call loan market. Thus, it appeared that the money trust influenced the call loan market to promote the very securities that it underwrote.

Third, the subcommittee concluded that the money trust wielded influence through representation on many corporate boards. And by membership on the boards of competitors in the same industry, the money trust could promote a degree of coordination inconsistent with open competition. The evidence in support of this was a matrix of corporate directorships. The committee found that officers of the First National Bank were board directors in 49 corporations, with capital of $11.5 billion. For National City Bank, the figures were 41 corporations and $10.5 billion. J. P. Morgan & Co.’s officers were directors in 112 corporations with capital of $22.5 billion. In 1914, Louis Brandeis noted that in comparison the total capitalization of the NYSE was only $26.5 billion. Brandeis concluded:

The operations of so comprehensive a system of concentration necessarily developed in the bankers’ overweening power. And the bankers’ power grows by what it feeds on. Power begets wealth; and added wealth opens ever new opportunities for the acquisition of wealth and power. The operations of these bankers are so vast and numerous that even a very reasonable compensation for the service performed by the bankers, would, in the aggregate, produce for them incomes so large as to result in huge accumulations of capital… . We must break the Money Trust or the Money Trust will break us.23

Figure 21.2 Structure of the Money Trust Presented by the Pujo Committee

SOURCE: “Exhibit 244: Diagram Showing Principal Affiliations of J.P. Morgan & Co. of New York, Kidder, Peabody & Co. and Lee, Higginson & Co. of Boston, First National Bank, Illinois Trust & Savings Bank, and Continental & Commercial National Bank of Chicago,” Money Trust Investigation: Investigation of Financial and Monetary Conditions in the United States Under House Resolutions Nos. 429 and 504 Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Banking and Currency, U.S. House of Representatives (1912–1913), February 25, 1913. Downloaded from St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, FRASER Archive, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/money-trust-investigation-80/exhibit-244-diagram-showing-principal-affiliations-jp-morgan-co-new-york-kidder-peabody-co-lee-higginson-co-boston-first-national-bank-illinois-trust-savings-bank-continental-commercial-national-bank-chicago-23677.

The overarching idea of control of finance by a small group of Wall Street insiders proved to be both compelling and threatening. The octopus‐like structure was depicted by the committee in drawings, such as given in Figure 21.2—though unreadable to anyone without a magnifying glass, the diagram showed the linkage of railroads (lower left), large manufacturing firms (upper left and upper right), and banks, trust companies, and insurance companies (lower right).

Proposals for Change

The majority report of the committee concluded its summation of findings with two proposals for new legislation. The first was an amendment of the original national banking laws to forbid actual or hypothetical practices that had been discussed in the hearings. These included discriminatory terms of loans, credits in support of the control of industry prices, terms of membership in clearinghouses, prohibition on bank directors borrowing from their own banks, forbidding banks to underwrite the offering of securities, and so on. The second proposed law involved the prevention of the use of the postal system, telegraph, or telephone to commit fraud on stock exchanges.

Notably absent from the suggested laws were regulations on the deployment of bank reserves. The immobility of bank reserves and gold currency was at the heart of the Panic of 1907. The absence reflected the division of labor within the House Committee on Banking and Currency: one subcommittee, led by Pujo, would investigate the thesis of industrial control by financial interests. Another subcommittee, led by Carter Glass, a representative from Virginia, took up Nelson Aldrich’s proposal of a “National Reserve Association.” Buoyed by the publicity and momentum from publication of the Pujo committee report, Untermyer lobbied behind the scenes to reopen and expand the hearings and to address central banking.

However, President Woodrow Wilson demurred. Inaugurated on March 4, 1913, he faced the task of installing a new administration and channeling a torrent of energy stimulated by his progressive agenda. Mexico, the next‐door neighbor, had convulsed into revolution. Tariff reform, implementation of a progressive income tax, plans for a Federal Trade Commission, and reform of the financial system vied for his attention. Wilson decided that Carter Glass should carry forward the work on a central bank. Accordingly, the recommendations of the Pujo Committee faded, to be revisited later after these other initiatives had matured.

Reaction to the Report

Public reaction to the publication of the majority report flared and subsided quickly. Major newspapers covered the report and its critics. One Republican representative called the report “bunk, pure and simple.”24 J. P. Morgan & Co. responded with a vigorous defense in a memorandum to Pujo: it denied the “vestige of truth” in the idea of a money trust, attributed problems in the financial system to inappropriate regulation, and argued that meeting the capital needs of large corporations required cooperation among financial firms.25 The committee’s activities had been reported in detail previously and the substance of the final report had been anticipated.26 In his inaugural address on March 4, Woodrow Wilson offered no direct comments on the Pujo findings. Thereafter, the establishment of the new administration occupied the headlines.

However, in the longer run, the “Money Trust” hearings proved to be enormously influential. They pioneered the quantitative analysis of the financial sector, setting a standard for many future investigations. They dominated newspaper headlines for months, as Wall Street leaders were called to testify before the committee. Of particular interest was the power of the New York Clearing House during the Panic of 1907 “to pronounce sentence of death upon every financial institution in [New York City].”27 The findings of this investigation inflamed the public and seeped into the presidential election campaign of 1912. The Democratic Party candidate, Woodrow Wilson, said,

The great monopoly of this country is the monopoly of big credits… . A great industrial nation is controlled by its system of credit. Our system of credit is concentrated. The growth of the nation, therefore, and all our activities are in the hands of a few men who, even if their action be honest and intended for the public interest, are necessarily concentrated upon the great undertakings in which their own money is involved and who necessarily, by very reason of their own limitations, chill and check and destroy genuine economic freedom. This is the greatest question of all, and to this, statesmen must address themselves with an earnest determination to serve the long future and the true liberties of men.28

Did the Investigation Prove What It Claimed?

Subsequent critical analysis has challenged the hearings’ conclusions. Historian Vincent Carosso (1973) pointed out that the Pujo hearings operated with no particular definition of a money trust, a defect that led to rambling, expansive, and poorly tested assertions. Untermyer acknowledged in December 1911 that “money trust” was a “loose, elastic term” but that it meant to indicate “a close and well‐defined ‘community of interest’ and understanding among the men who dominate the financial destinies of our country and who wield fabulous power over the fortunes of others through their control of corporate funds belonging to other people.”29 Carosso called Untermyer’s definition “economic nonsense and demagoguery.”30

Mary O’Sullivan (2016) noted big gaps in the data presented, a focus on only a few banking houses, and a failure to compare their impact to the entire size of the market. For instance, during the hearings, Jacob Schiff had argued that although the money trust banks held many board seats, they were too few on any single board to have decisive influence on the direction of a company. To test that assertion, O’Sullivan computed the percentage of board seats of all publicly listed corporations in 1913 that were held by J. P. Morgan & Co., City National Bank, and First National Bank, the core of the money trust. The percentages, displayed in Figure 21.3, support Schiff’s point. The money trust banks enjoyed places at many board tables, but not the kind of voting muscle consistent with corporate dominance.

O’Sullivan concluded, “Overall, there is little evidence to support the Pujo report’s claim that the money trust’s numerous directorships both enabled it, and motivated it, to ‘throttle’ competition. The investigation did not establish that the practice of putting bankers on boards was distinctive to the money trust nor that, as a general rule, bankers dominated the boards where they were represented.”31

Figure 21.3 Money Trust Board Representation

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data given in O’Sullivan (2016), p. 302, based on Pujo Investigation Table of Interlocking Directorates, Exhibit 134‐A, and Moody’s Manual.

Similarly, O’Sullivan studied the total underwritings by money trust firms as a percentage of all U.S. corporate issues from 1908 to 1912. Figure 21.4 shows that the dollar proceeds amounted to about a third of all issues; and the number of issues was about 10 percent.

The disparity between dollar proceeds and the number of underwritings is explained presumably by underwriting fewer but larger securities offerings by the money trust firms.

The Pujo hearings’ conclusions stumble on the vagueness of market control: What percentage share of market is too much? Earlier, Gary and Frick believed that U.S. Steel’s acquisition of TCI avoided opposition by Roosevelt if it did not exceed a 60 percent share of market. The underwriting shares of the money trust of 10 percent to 35 percent pale in comparison. O’Sullivan concluded,

[T]he money trust did not dominate the underwriting and distribution of corporate securities to the extent that the Pujo report claimed. Its influence was greatest among giant railroad issues, but even there it was not as overwhelming as the Pujo report asserted. Moreover, the structural changes underway in the primary market—the shift from railroads to industrials and from larger to smaller issues—mean that it was evolving in ways that tended to diminish the money trust’s dominance.32

Figure 21.4 Money Trust Underwritings

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data given in O’Sullivan (2016), p. 285.

Impact

The hearings generated huge media coverage. A computer search of newspaper articles containing the phrase “money trust” yielded 9,001 hits for 1911, 8,871 for 1912, and 7,989 for 1913.33 As Figure 21.5 shows, the number of books mentioning the phrase spiked in tandem with the Panic, reaching a peak in 1913, then peaked again in the 1930s, and remained in the public’s mind for decades.

Jurist Louis Brandeis quickly distilled the findings of the Money Trust Investigation into a series of articles, published in Harper’s Weekly. The articles mobilized public sentiment in the spring of 1913 on behalf of financial reform. Brandeis collected the articles into a book, Other People’s Money, published in 1914, that became one of the pillars of the Progressive Movement. Progressives feared that through the workings of a money trust, underwriting business would be directed to a few favored firms, investment capital in the United States would be channeled to the advantage of a few powerful business leaders, and control of large corporations would go to the money trust. All of this was consistent with the thesis of William H. “Coin” Harvey in 1899.

Figure 21.5 Frequency of Occurrence of the Phrase “Money Trust,” 1800–2020

NOTE: This graph displays the frequency of occurrence of the phrase “money trust” found in a corpus of English language printed sources.

SOURCE: Google Books Ngram viewer, downloaded June 21, 2022 from https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Money+trust&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2CMoney%20trust%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2CMoney%20trust%3B%2Cc0.

The political reaction to the Panic of 1907 normalized the idea of the money trust and thrust it to center stage in the debates over stabilization of the financial system and the soundness of U.S. currency. For a century or more the idea underpinned public policy debates about the financial system and its regulation.

Notes

- a. One invited witness, William Rockefeller, claimed illness. Perhaps sensing a ruse, Untermyer doggedly demanded medical opinions from two different doctors, who attested to Rockefeller’s grave condition (apparently temporary, for he would live 10 more years). Even then, Untermyer and Pujo traveled to Rockefeller’s residence intending to take sworn testimony from his bedside. The resulting interview lasted a few minutes with Untermyer concluding that “I should be unwilling to go further with the examination at this time, from what I have just heard and observed as to Mr. Rockefeller’s condition.” [Money Trust Investigation, 1913, pp. 2141–2142.]

- b. We analyzed the distribution of Pujo witnesses based on the inches of text in the Money Trust Investigation that were devoted to dialogue between Untermyer and each of the witnesses. Percentages were calculated as the sum of inches for a witness, divided by the sum of inches across all witnesses. The distribution of the La Follette list of “financial rulers” reflects the number of each group as a percentage of the total sample.

- 1. W. H. Harvey (1899), p. 130.

- 2. “100 Men Rule Nation, Says La Follette: In Standard Oil and Morgan Groups, and Plotted the Recent Panic, He Declares,” New York Times, March 18, 1908, p. 1.

- 3. “Bought by Morgan: Banker Gets Control of Equitable Life Society,” Washington Post, December 3, 1909,” p. 1 and “Concerning New Money Power,” Wall Street Journal, December 25, 1909, page 6.

- 4. “Bought by Morgan: Banker Gets Control of Equitable Life Society,” Washington Post, December 3, 1909, p. 1.

- 5. “Money Institutions Combine,” Chicago Defender, January 1, 1910, p. 1.

- 6. “Newest Combine in Money Trust,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 19, 1909, p. 5.

- 7. “Bought by Morgan,” p. 1.

- 8. McCulley (1992), p. 179.

- 9. “Bank of Commerce to Morgan Group: Plans All Made,” New York Times, p. 1.

- 10. “Great Banking Merger Planned,” from the New York World. Washington Post, March 15, 1911, p. 6.

- 11. See A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh (New York: Putnam, 1998).

- 12. “Wants a Bank Inquiry: Republican Insurgent Sees Something Behind the Aldrich Plan,” New York Times, July 9, 1911, p. 6.

- 13. “Big ‘Money Trust” Attacked by Congressman from Minnesota,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, 1911, p. 2.

- 14. “Untermyer to Lead Money Trust Inquiry . Has Expressed His Views,” New York Times, January 5, 1912, p. 1.

- 15. “Money Trust Investigation,” House of Representatives, Subcommittee of the Committee on Banking and Currency, Part 1, p. 4.

- 16. O’Sullivan (2015), p. 2.

- 17. Carosso (1973), p. 424, citing the argument of Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays (New York: Vintage, 1967), p. 29.

- 18. “Death of J.P. Morgan No Surprise to Wall Street: Long Illness Had Prepared Financial Community as Well as Friends for Inevitable End,” Wall Street Journal, April 1, 1913, p. 1.

- 19. United States Congress. House. Committee on Banking and Currency, 1865–1974, Pujo, Arsène Paulin, 1861–1939 and Sixty‐Second Congress, 1911–1913, “Part 15, Pages 1011–1101” in Money Trust Investigation: Investigation of Financial and Monetary Conditions in the United States Under House Resolutions Nos. 429 and 504 Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Banking and Currency, House of Representatives, (1912–1913) (December 19, 1912), https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/80/item/23671.

- 20. Strouse (New York: Random House, 1999), p. 671.

- 21. O’Sullivan (2016), p. 291, summarizes the deposit funds and other resources on which the $1.6 billion estimate is based.

- 22. The M2 money supply estimate for 1913 of $15.73 billion is given in U.S. Historical Statistics, Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce, 1975, Part 2, Series X 410‐419, p. 992.

- 23. Brandeis, (1914), pp. 23 and 201.

- 24. “Untermyer Scored in House: Pujo Committee Counsel Denounced,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 28, 1913, p. 7.

- 25. “Morgan Defense in as Pujo Finishes,” New York Times, February 28, 1913, p. 7.

- 26. “No Surprise Is Felt at Pujo Proposals,” New York Times, March 1, 1913, p. 3.

- 27. Quotation of chief investigator Samuel Untermyer in McCulley (1992), p. 266.

- 28. This quotation of Woodrow Wilson corresponds to statements made in his campaign speeches and is reproduced in his book The New Freedom: A Call for the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People (New York and Garden City, NJ: Doubleday Page and Company, 1918), p. 185, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_New_Freedom.html?id=MW8SAAAAIAAJ.

- 29. Quoted in Carosso (1973), p. 423 from the Commercial & Financial Chronicle, XCIII (December 30, 1911), p. 1756.

- 30. Ibid., p. 437.

- 31. O’Sullivan (2016), p. 309.

- 32. Ibid., p. 290.

- 33. These numbers likely underestimate the volume of media attention to the phrase “money trust.” We tallied the number of articles referencing “money trust” using the search engine for ProQuest Historical Newspapers. This source included only 10 publications: New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Chicago Defender, Chicago Tribune, Norfolk Journal and Guide, Pittsburgh Courier, NY Amsterdam News, Baltimore Afro‐American, Washington Post, and The Guardian & Observer.