The Political Bubble of the Crisis of 2008

Rising home values have added more than $2.5 trillion to the assets of the American family since the start of 2001. The rate of homeownership in America now stands at a record high of 68.4 percent. Yet there is room for improvement. The rate of homeownership amongst minorities is below 50 percent. And that’s not right, and this country needs to do something about it.

—President George W. Bush, remarks at the signing of the American Dream Downpayment Act of 2003

I’m delighted to be here, along with Frank Raines, my OMB Director, who used to spend some time with some of you, and Gene Sperling and others on our staff.… Now, we are seeing a remarkable increase in the circle of opportunity. In addition to reaching the highest level of homeownership in history, millions of Americans have been able to refinance their mortgages, which has amounted to billions and billions of dollars in tax cuts for families, putting more money in their pockets, freeing up more for investment and savings. Access to capital has spread to minorities who for years have been locked out of the economy.… We do see increasing homeownership rates for minorities now and I hope it will continue. Our capital markets are the strongest in the world, and clearly, they have played a major role in helping us to do well in this new economy.

—President Bill Clinton, remarks to the Mortgage Bankers Association of America, 1998

THE THREE I’S— IDEOLOGY, INSTITUTIONS, AND INTERESTS—combined to inflate the bubble that led to the financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuing Great Recession. The caldron was stirred for forty years, going back to the privatization of Fannie Mae in 1968. The last major ingredient was the 2000 addition of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act. We now recount how the Three I’s resulted in errors of commission in the form of deregulation and poor regulatory structures, and errors of omission in the form of failure to regulate new products and to enforce existing law. We emphasize that the bubble grew because egalitarian ideology, the “ownership society” side of free market conservatism, converged with crony capitalism to produce a rare but dysfunctional instance of bipartisan policy consensus.

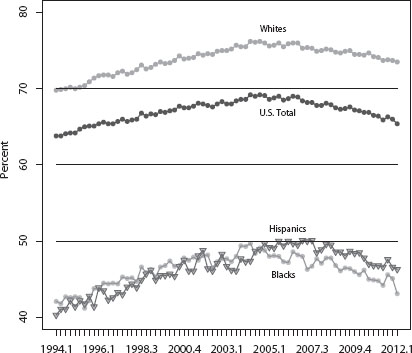

When the giant bubble emerged at the turn of the new century, the main stirrers were the Time magazine–designated “Committee to Save the World” of Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin, and Larry Summers. The committee played the role of Macbeth’s witches: they turned boundless prosperity and McMansions into worthless eyes of newt and toes of frog. The multi-trillion-dollar creation of wealth cherished by President Bush quickly evaporated. Homeownership rates in the United States were no higher in early 2012 than in 1996, and for blacks they were slightly lower. Hispanics fared somewhat better, but their homeownership rate nonetheless fell back to its 2001 level. In broad categories of American society, no group benefited from the policies of the Clinton and Bush years. (See figure 5.1.)

Another notion of the investor society was that Americans would prosper by investing in equities.1 How would Americans have done by making buy-and-hold investments in the nation’s largest insurance company, its largest commercial banks, its largest investment banks, or the two very large privatized government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? These would have appeared to be safe investments. After all, their directors and executives included some of the nation’s most esteemed public servants, such as Robert Rubin, Richard Holbrooke, Franklin Raines, and Martin Feldstein. Of course, except for some of the 1 percent, Americans cannot participate in private equity and hedge funds. So the big financial firms would appear to be the way into the financial sector for Joe the Plumber.

Figure 5.1. Homeownership rates by race and ethnicity, 1994–2012. Homeownership rates have continued to decline beyond the end of the 2007–9 recession. Homeownership rates in 2012 are lower for all groups than the rates in 2002. African American homeownership rates have had a particularly steep decline and have fallen back to the level of the mid-1990s.

Source: Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey, Series H-111, Bureau of the Census.

In table 5.1, we benchmark these investments in two ways. First, we compare returns between the end of 1999—just after Goldman Sachs, the last of the major investment banks to go public did so—and the end of 2011. Second, to give investors a longer-run perspective, we moved the start date back a decade to the end of 1989. We measured returns in two ways. First, we computed the total percentage increase in the price of common stock. This, of course, can be negative. Negative returns are bounded by –100, which corresponds to a total wipeout, as was the case for Washington Mutual (WAMU). Second, we added in dividends. We assumed no reinvestment of dividends. If, of course, the investor had reinvested the dividends in the stock, the returns would have been much worse for most of the firms. The table accounts for all stock splits, including the ten-for-one reverse split of Citigroup, necessary to keep that firm from becoming a penny stock.

TABLE 5.1.

Returns for selected financial firms

Notes: *Morgan Stanley 12/31/1993–12/31/2011; **WAMU, Wachovia until 2008.

If the investments were made at the end of the 1990s, they would have been a disaster, with the exception of Wells Fargo. All the other firms had negative stock returns, typically far more negative than the S&P 500 index, shown for comparison. Even with dividends, the returns are negative, with the exception of Wells and Goldman Sachs. The latter’s return of 7 percent was a paltry .75 percent on an annualized basis. So where did the money go? Goldman Sachs’s partners made money in the initial public offering. The partners and other employees also had substantial income and bonuses over the period. So the “investor society” member would have provided financing to the 1 percent member inside Goldman Sachs. Morgan Stanley was worse than Goldman. Two other major investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, and the two GSEs, not shown in the table, were, of course, much worse.

Over the longer period, from 1989, things look better, largely because of the better performance in the 1990s. Even over this extended period, the firms lagged the S&P 500, again with the exception of Wells Fargo. Dividends, with the exception of those of American International Group (AIG), overcame the fall in stock price to lead to positive total returns. But the returns were not huge. An annualized return of 9.28 percent is implied by the 640 percent total for Citigroup. For Bank of America, it was only 3.82 percent.

As the large financial firms grew since the 1990s, they generally performed poorly for the investor society. The firms have largely survived intact as organizations even if their equity holders have taken it on the chin. Why have they survived? Their executives and board members surely know the answer.

Thus, after the crash, long-term investors in the big financial firms were crushed. Homeownership regressed back to the level of the mid-1990s. Average Americans might have benefited in some other way if they were better able to consume goods other than housing. But this was not the case.

From 1972 to 1999, median household income (adjusted for inflation) grew steadily, with hiccups, as shown in figure 5.2. Income inequality increased dramatically in the last two decades of the twentieth century as the income of the top quintile grew much faster than the median. But income gains were generally widespread. From 1972 to 1999, median household income, adjusted for inflation, increased from about $45,000 to $53,000. But the first decade of the new century was a lost one. By 2010, median income had not returned to the 1999 level and was below $50,000.

Figure 5.2. Median household income and average income of top quintile, 1972 to 2010 (in 2010 dollars). Income never recovered to the level it reached at the end of the twentieth century under President Clinton. During the eight years of the Bush presidency (2001–8) it recovered somewhat but then fell sharply during the first two years of the Obama presidency.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements.

Just as incomes increased across the board until the new millennium, the stagnation and loss of the last decade has been broad. Even the core constituency of the Republican Party—upper-income whites2—suffered from the decade’s experiment with unfettered financial capitalism. Incomes among top-quintile whites collapsed with the crisis and ensuing recession. Yet, as indicated by the results of the 2010 congressional elections, the losses did little to undermine the commitment of those voters to the Republican Party and free market conservatism.

The lethal concoction that destroyed the investor society and the broader standard of living had five components—all rooted in our Three I’s. The first was deregulation that permitted innovative new financial instruments, such as exotic mortgage products, collateralized debt obligation tranches, and credit default swaps to emerge without meaningful regulation. The second was deregulation that permitted financial firms to engage in a riskier range of activities. The third was a reduction in the monitoring capacity of regulators, either through deliberate neglect, as reflected in the tenures of Alan Greenspan at the Federal Reserve and Harvey Pitt and Christopher Cox at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), or as a result of the failure of staffing and budgets to expand at the same rate as the markets they were supposed to regulate. The fourth was the shifts in competition policy that allowed the creation of financial institutions that were too big (and too politically powerful) to fail. The fifth component was the privatization of government financing of mortgages through Fannie and Freddie, which created two additional too-big-to-fail institutions.

We can tell much of our story about the lethal concoction that devastated the economy from 2007 to 2009 by relating the history of a single bank account. In 1993, one of us moved to Princeton, New Jersey. Out of convenience he opened a checking account at the bank with a branch closest to his office, New Jersey National. Given the insurance of deposits and the lack of banks with national ATM networks, there was no need to shop carefully. In 1994, the Riegle-Neal Act initiated a wave of bank mergers. Subsequently, New Jersey National, locally based in Trenton, was acquired by CoreStates, based in Philadelphia. CoreStates was later acquired by First Union, which in turn was gobbled up by Wachovia in 2001. The account at tiny New Jersey National became an account at the fourth largest commercial bank in the country.

Wachovia also acquired firms from outside of commercial banking, such as Prudential Securities. But its biggest trouble started in its mortgage business. Wachovia’s acquisition of Golden West Financial exposed it to tremendous risks in the mortgage market, as Golden West was the innovator of the so-called pick-a-payment mortgage with a negative amortization option (through which the borrower could pay less than the interest owed, and the principal would increase).

Wachovia sought profits in many ways other than acquisitions. It facilitated check cashing in identity theft cases and money laundering by international drug cartels. It rigged bids for municipal bonds.3 It engaged in illegal practices with telemarketers.4 Of course, the top executives at Wachovia claimed that they bore no responsibility for these activities. The malfeasance was just the work of a few “rotten apples” or “reckless few” among thousands of hardworking and honest employees. The firm was slapped on the wrist with fines or settlements, and the federal government accommodated. But by growing as it did, moreover, Wachovia became too big to fail. As is typical of the ever-spinning revolving door, Paulson’s undersecretary at the Treasury, Goldman Sachs alumnus Bob Steele, presided over the last six months of Wachovia’s existence. Unlike the smaller bank Washington Mutual, whose equity holders lost everything, Wachovia’s shareholders received $7 a share when Wachovia was acquired by Wells Fargo in 2008. The acquisition price was just a sop, as Wachovia had been selling for more than $37 at the beginning of the year and more than $56 a share in early 2007. Quite a haircut, but not WAMU’s beheading.

The acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo echoes the circumstances of the acquisition of National City by PNC that was discussed in the introduction. Part of what made Wachovia an attractive target for Wells Fargo was that the Internal Revenue Service, with Paulson’s blessing, made an on-the-spot change in the taxation of inherited losses.5 The account at tiny New Jersey National is now a Wells Fargo account.

Wachovia’s fall and subsequent rescue might have been avoided either if firms like Golden West had not been allowed to issue the dubious adjustable-rate interest-only mortgages or if the acquisition of Golden West had been blocked by regulators. Perhaps if regulators had prevented the acquisition of First Union, Wachovia might have been small enough to fail. If there had been better monitoring of Wachovia, there might have been less identity theft and money laundering. At least, the firm should have paid a higher price for lacking the necessary internal controls. Wrist slaps only abet the culture that makes such incidents far too common. Ultimately Wachovia failed as the bubble popped and politics, not the market, determined that Wachovia was to be allocated to Wells Fargo and not to another suitor, Citigroup.

There was nothing special about Wachovia. The same chronology could be repeated for dozens of other financial firms. Just as Wachovia was crippled by Golden West, Bank of America was badly wounded by its acquisitions of Countrywide Financial and Merrill Lynch. When an industry becomes populated with Wachovias and Bank of Americas, the case for relying solely on market discipline and self-regulation unravels.

How did politics fuel Wachovia and other firms in the bubble?

Debate over the origins of the bubble and the financial crisis has quickly become, consistent with our findings in Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches, ideologically driven as much as based on fact. The findings of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, created by Congress and the president to “examine the causes of the current financial and economic crisis,” typify the ideological debate. The Democratic-appointed majority blamed the failure of private sector markets in mortgage origination, securitization, and swaps—that is, firms like Wachovia. The minority report by Republican appointees downplayed the role that deregulation played in the crisis, stressing instead global fiscal imbalances that lowered the cost of credit. In a separate dissent, Republican minority commission member Peter Wallison blamed the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie and Freddie, as well as liberal policies such as the Community Reinvestment Act.

Our own view is that there is certainly more than enough blame to go around, but that Wall Street should be nailed to the highest pole. However, to understand the bubble one does need to consider all the changes in government policy that affected the housing market. So we begin there.

The Housing Market’s Off-Budget Subsidy

Roughly speaking, the government can support housing for its citizens in two ways. First, it can do so directly by building and then selling or leasing its own housing units. Second, it can do so by subsidizing the private sector. One way to subsidize housing would be direct transfers to individuals as we do for welfare, food stamps, social security, and unemployment insurance. These expenditures would be on budget. Congress would have to appropriate the funds. Another way would be to make off-budget subsidies both to individual home buyers and to firms involved in the construction, mortgage lending, and rental markets. From time to time, the U.S. government has used both mechanisms. But by and large policy has moved away from public housing toward private subsidies. Private subsidies have, in turn, largely been of the off-budget variety, given public aversion both to redistribution and to taxation. No doubt some of this shift reflects the major shortcomings of government-run housing projects. But the shift toward a subsidy-based system with an emphasis on ownership has important political underpinnings. Not only was the policy shift responsive to the economic interests of the housing sector but it was sustained by the marriage of egalitarian ideology and the “ownership society” offshoot of free market conservatism.6

The housing industry, which includes not only those directly involved in housing finance but also real estate agents and developers, has long been politically powerful. It has succeeded in obtaining huge direct and indirect support from the government. The largest housing subsidy is the income tax deductibility of home mortgage interest payments and property taxes. Demonstrating its political clout, the housing industry was able to preserve the home mortgage interest deduction in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 when the deductibility of all other consumer interest was eliminated.7 Not surprisingly, this continued subsidy spawned new financial products such as home equity loans and lines of credit. The debt acquired from home equity loans was responsible for many homeowners “going underwater” (i.e., having mortgage debt that exceeded their home equity) when the bubble burst.

An important source of the housing industry’s political power is that there is little transparency about the nature and magnitude of off-budget subsidies.8 The power of the housing lobby is not limited to the federal level. For example, some state governments, notably those of Texas and Florida, further subsidize housing by exempting home equity from creditors in personal bankruptcies. In states that exempt large amounts of equity, the real estate lobby has fought hard against a national bankruptcy standard. Just as the mortgage interest tax subsidy does, the home equity bankruptcy exemption distorts the housing market by making homeownership relatively more attractive than other equity investments and renting.9 The industry was also well served by the taxpayer revolt that occurred in many American states, starting with Proposition 13 in California in 1978, closely followed by Proposition 2½ in “Taxachusetts.” These revolts resulted in limitations on property taxes. The subsequent shift from property taxes to sales taxes provided yet another subsidy for homeownership.

Other government policies also increased the demand for housing in the lead-up to the crisis. Monetary policies targeting low interest rates, per the Fed’s response to the 2001–2 recession, reduced the cost of mortgages. The reduction in income and loan-to-value standards for qualifying for a mortgage increased the number and size of mortgages. But the most debated policy link to the crisis concerns the role played by the so-called government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These entities, which we discuss in more detail below, subsidized the housing market by purchasing certain qualifying mortgages from lenders. Lenders in turn used the proceeds of these sales to issue more mortgages, which lowered borrowing costs and stimulated housing demand. The subsidy embedded in Fannie and Freddie was enhanced by the ultimately correct perception that the government guaranteed their debt. This guarantee reduced their borrowing costs below those of other corporate borrowers.10 So the mortgage industry, as symbolized by Countrywide Financial’s CEO Angelo Mozilo’s full-page color photograph in the 2003 Fannie Mae annual report, provided crucial political support for the GSEs.

In short, a variety of government policies favor housing. Interests fight for these policies.

Government housing policy also reflects ideology. One strand stems from the egalitarian ideologies typically associated with the political left. Egalitarians view adequate housing as an entitlement, like nutrition, schooling, and medical care. Of course, housing could be provided directly through publicly owned rental housing or on-budget rent subsidies. That was the initial federal response to housing problems. The first federal housing programs originated in the Great Depression when tax rates were relatively high, political polarization was low, and the belief in government effectiveness was very high. In the last thirty years, however, real federal on-budget housing expenditures have remained relatively constant in inflation-adjusted dollars despite large increases in the American population.11 The lack of growth of the on-budget housing subsidies reflects both the decline in support for tax rates that would generate the required revenue and the association of many public housing projects with violence and drug use, as illustrated by the notorious Cabrini-Green project in Chicago.12

A second ideological strand, this one from the right, also fostered the shift in federal policy toward the support of homeownership. Many conservatives believe that homeowners are better citizens than renters because they have a higher stake in their communities.13 So advocates of an “ownership society” such as the late Jack Kemp (Bob Dole’s vice presidential running mate in 1996 and a former secretary of Housing and Urban Development) argued that government should aggressively support homeownership and the privatization of public housing projects.

There is no logical reason for government housing subsidies to take the form they did. In principle, a switch from public rental housing to owner-occupied housing could have been accomplished transparently and on budget. For example, every citizen could be given a once-in-a-lifetime $50,000 down payment grant that, coupled with strict loan-to-value standards, would largely eliminate incentives for strategic default. But the aversion to direct redistribution left federal policy directed at off-budget policies that primarily supported homeownership through a loosely regulated mortgage market. As we will see, the decision to promote homeownership off budget helped foster the creation of the Byzantine sorts of financial products that opened the road to the crisis.

The Government-Sponsored Enterprises

The move to off-budget housing subsidies began in 1968 when Fannie Mae was fully privatized. The motivation was not a strong belief that a privately run Fannie would be more efficient. Rather it was an accounting trick perpetrated by the administration of president Lyndon Johnson. The privatization of Fannie removed its debt from the books of the federal government.14

Initially, Fannie was limited to the repurchase of government-insured Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgages. But by 1970 the government permitted Fannie to buy mortgages directly from private issuers. At the same time, Congress created Freddie Mac to compete with Fannie Mae.

The goal of better access to mortgage credit for minorities led to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977, passed under President Jimmy Carter. The act required institutions insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to stop redlining, a banking practice that discriminated against loan applications from minority neighborhoods. But the CRA did not require either the GSEs or other financial institutions to make high-risk loans to minorities.

In the 1990s Congress began pushing the GSEs into financing low-income housing. The Housing and Community Development Act of 1992 passed under George H. W. Bush and was expanded during the Clinton administration. This act required the Housing and Urban Development secretary to establish goals for each of the GSEs for the purchase of mortgages for low- and moderate-income families. Title VIII of that act (known as the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act) encouraged a greater number of loans where only 5 percent down payments were required.15 Again, we emphasize that this expansion was completely off the federal budget. Over time, the loan portfolios of Fannie and Freddie became increasingly risky. Numerous warnings were disregarded in part because the GSEs hid the risks by manipulating their accounting. The combination of implicit government guarantees and too-rosy accounting numbers drew large numbers of private investors to the GSEs. Fannie Mae’s stock rose to more than $86 a share in 2000, before its accounting deceptions became public. Although the stock never fully recovered, its price was as high as $67 in 2007. But now that Fannie is in government receivership, its remaining private-sector stock trades over the counter for less than a quarter.

Many observers argue that Fannie and Freddie, for all their problems, took on less risk than did many non-GSE firms that were into mortgage origination and securitization.16 But the privatization of Fannie and Freddie abetted the crisis in several ways. First, they were open to holdings by other financial companies. Citigroup held 6.3 percent of Fannie’s common stock in 2006 and 2007.17 SEC filings do not disclose whether this investment represented client holdings or a direct investment, but any direct investment would not have provided liquidity to Citigroup as both firms went down.

Second, even if Fannie bought only relatively good mortgages from Angelo Mozilo’s Countrywide and others, the purchases provided resources for these firms to originate more loans that could then be foisted off on the private mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market.

Third, resources were also freed up for the private MBS market as the GSEs increasingly bought back their own MBS issues. The profits of the two GSEs originally came from the guarantee fees they charged on the MBSs that were privately held. But, as time progressed, the profits were largely generated by the spread between the interest on the repurchased MBSs and the low borrowing costs enjoyed from the government guarantee. As Dwight Jaffee pointed out in 2003, the strategy exposed Fannie and Freddie to interest rate risk.18 The gamble contributed to the two firms’ collapse and subsequent nationalization. Future taxpayer costs are to be determined.

Fourth, Fannie’s lower borrowing costs, abetted by its implicit government guarantee, gave it a competitive advantage over private MBS issuers when it came to purchasing less risky mortgages. This competitive advantage did not extend to the riskier subprime mortgages that the GSEs were not allowed to buy, which in turn may have encouraged the private label securitizers to focus on that part of the market.19

In the good times, Fannie and Freddie were also preserved and protected by institutions, most likely fostered by future interests embedded by crony capitalism. Not surprisingly, Democrats were opposed to reform. But Newt Gingrich (R-GA), the Speaker of the House, and Michael Oxley (R-OH), the chair of House Financial Services, used their institutional power to block reform in Republican-controlled Congresses. Speaker Gingrich kiboshed a mid-1990s attempt to levy fees on the GSEs to pay for the costs of the savings and loan (S&L) bailout. As a result those costs were passed on to general taxpayers.20 In 2002, House Financial Services Subcommittee on Capital Markets chair Richard Baker (R-LA) introduced a reform bill. This legislation got nowhere, after it failed to gain Oxley’s support.21 In 2005, the House and Senate made attempts at reform, but no legislation reached the president’s desk. In retirement, Oxley became a lobbyist for NASDAQ and the private sector’s “self-regulator,” the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. Gingrich’s 2012 Republican presidential nomination bid was damaged by the revelation that his Gingrich Group had previously received a $1.6 million fee from Freddie Mac.

Interests within the GSEs were also active in maintaining gridlock. Fannie, during the 1991–2004 reigns of James Johnson and Franklin Raines, was a money machine for career Democrats. Replacing Raines with Daniel Mudd did not result in a clean house. Mudd, two other Fannie executives, and three Freddie executives were charged with securities fraud by the SEC in December 2011.22 Although the GSEs were most entrenched within the Democratic Party, they always sought bipartisan support by cultivating ties to important Republican policy makers.

Support of Fannie and Freddie extended beyond elected policy makers to the academic policy community. Three career Democrats, Nobel Prize Laureate Joseph Stiglitz and Peter and Jon Orszag, wrote a 2002 Fannie Mae report in which they claimed there was less than a 1 in 500,000 chance that Fannie could fail. The report was published twice, once with a foreword by FDIC chief Sheila Bair and again with a foreword by Fannie senior vice president Paula Christiansen. The two forewords were identical, word for word.23 Fannie also blessed itself with a study by Glenn Hubbard, chair of the Council of Economic Advisors under George W. Bush and now dean of the Columbia Business School, and adviser to presidential candidate Mitt Romney.24

These reports need not have been disingenuous. Indeed, they were based on state-of-the art economic analysis. (On the other hand, the paper from Stiglitz and the Orszags was quickly criticized by UC–Berkeley Haas Business School professor Dwight Jaffee.25) Rather, our concern with these kinds of studies is that they ignore the political context. The blue-ribbon endorsements emboldened the GSEs to pursue their course more aggressively as they were inoculated further from political interference. The groupthink forewords only added to these political risks.

The semiprivate status of Fannie and Freddie has long been a source of political risk. When Fannie was privatized, free market conservatism and deregulation had not taken root—Barry Goldwater’s brand of free market conservatism was soundly rejected at the polls in 1964. The privatization was just part of taking the housing subsidy off the books. But once the GSEs were created, gridlock rendered reforming them very difficult. Although the pop of the bubble forced the GSEs back into the public sector, their ultimate status is unclear as the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act left the issue untouched. Effective reforms will be unlikely in the current polarized environment.

Deregulation and Innovation in the Private Sector

Despite the complicity of housing policies, the bubble would not have happened without the substantial deregulation of financial markets that took place over the past several decades. The main deregulatory actions centered on relaxing constraints on home mortgage products—most notably the lifting of interest rate caps and allowing adjustable rate mortgages; permitting mergers and acquisitions that concentrated the banking industry; and the complete deregulation of derivatives markets including mortgage-backed securities and swaps. At the same time, regulatory monitoring was diminished and new products were not proactively vetted.

There is an ideological aspect to this movement toward financial deregulation. Consider the electronics market, which is unregulated and works well. Consumers appear to make decisions without great harm. If competition results in the failure of certain firms (Digital Equipment, Gateway, RCA, etc.), there is no lasting loss to the economy. The idea that competition benefits consumers, central to free market conservatism, was applied—starting in the Carter years—to deregulate many markets, notably in transportation and telecommunications. Moreover, even if deregulation led to only a few large firms, the efficiency benefits might exceed the costs of monopoly power. Deregulation of the railroad industry, accomplished by the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, is seen as a great success, even if the United States today has only two major railroads in the east and two in the west. Conservative ideology, already in place before the presidency of Ronald Reagan, held that deregulated markets were good and that industry concentration was not bad per se.26

Now contrast the electronics industry with health care. We might allow consumers to make their own decisions: prescriptions would not be necessary, and drug manufacturers would not be monitored. The Food and Drug Administration would be abolished and anything could be sold. Megafirms, say Hospital of America or Citihealth, could operate facilities that any quack could rent to carry out surgery. Schools would not require that children be vaccinated. Extreme libertarians might support such an unfettered market like this but most Americans would not. First, information about quality is difficult to obtain, so most of us would like a reliable, disinterested party to inform us about the safety of a drug or the competence of a surgeon. Second, bad individual decisions, if they resulted in epidemics, generate “systemic risks.”

Deregulation of energy markets is instructive. The Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPACT) effectively repealed the Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA) of 1935, the electric-power equivalent of the Glass-Steagall Act. Its repeal generated large political risk. Under the PUHCA, most utilities were vertically integrated, generating, transmitting, and distributing electric power. EPACT permitted the industry to be restructured; whereby these three activities could be separated and run by independent firms.

The California “restructuring,” supported by Republican governor Pete Wilson and Democrats in the legislature, proved to be unworkable. Local utilities, such as the Pacific Gas and Electric Corporation (PG&E), were forced to sell off their generating capacity. But politics increased risk by not allowing the distributing firms to make long-term contracts for power. They could only buy power from wholesale generators on the instant, “spot” market. The distributors were also forced to hold rates low. The now infamous Enron Corporation moved into wholesale generation. In the absence of effective monitoring of the deregulated market, Enron deliberately manipulated the spot market for electricity by selectively shutting down power plants for “maintenance.”27 Blackouts ensued (but the vertically integrated “socialist” public power operations of Los Angeles and Sacramento were spared). PG&E filed for bankruptcy. Polarized blame-game politics, as outlined in chapter 4, came to the fore. Conservatives blamed Democratic governor Gray Davis, who only inherited the restructured market. Liberals blamed Enron. After the California fiasco, states put restructuring on hold. Restructured states rarely rolled back their deregulation plans. Those who had not restructured did not go forward. The outcome attests to the power of the status quo with American political institutions.

Financial markets appear to us to be closer to health care and electric power than to electronics. In a home purchase the consumer is making a decision of far greater economic import than is involved in the purchase of a smartphone. In making a decision about knee surgery or a home mortgage, the consumer has far less opportunity to learn than when she makes frequent purchases of paper towels. Choosing the wrong product offered by a greedy lender parallels receiving unnecessary surgery from a quack. Failure in financial markets can lead to systemic risk. Just like the power grid, the entire economy can black out.

When Congress, the White House, and the independent regulatory agencies turned to the deregulation of financial markets, it appears that they had electronics more than health care in mind. Moreover, as an ideology, free market conservatism does not fully admit the differences in these markets. And when these ideas were pushed by powerful interests, deregulated financial markets were the inevitable outcome.

One of the first regulatory changes that facilitated the bubble was, like the privatization of Fannie, motivated by a desire to shift a big problem off the federal budget. In this case, the problem was the crisis in the savings and loan industry. The thrifts, as S&L banks were known, were highly regulated. When the industry developed, S&Ls were largely nonprofits that were restricted to making fixed-rate residential mortgages and accepting deposits. The interest rates for both of these transactions were tightly regulated. But by the late 1970s, most thrifts were for-profit firms faced with increased competition for deposits, primarily from money market mutual funds. At the same time, the profitability of the thrifts was jeopardized when the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker pursued tight money policies to end the inflation of the 1970s. When interest rates spiked, the S&Ls were forced to pay high rates on their deposits while receiving low rates on their existing loan portfolios.

The federal government did not respond with prudential reform of the industry. That reform would have involved the industry’s deposit insurer, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), shutting down insolvent thrifts and paying off the depositors. But when the industry became insolvent, the FSLIC lacked the sufficient funds. Appropriating the funds would have been a politically unpopular addition to the federal budget deficit. So Congress and the president decided it was better to deregulate the industry and allow the thrifts to “gamble for resurrection.”

The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 was the first important step toward deregulation. This legislation sailed through the House of Representatives, with only thirty-nine members voting against final passage and fourteen voting against the conference report. The opponents were ideologically scattered. Similarly, only nine senators opposed passage.

The 1980 Act did reflect the tensions between local constituencies, described in chapter 4, and Wall Street. On the one hand, the Senate incorporated an amendment that promoted moral hazard for some federally insured institutions. The amendment striped the Fed of authority to impose reserve requirements on banks, largely small and local, that were not members of the Federal Reserve system. On the other hand, the 1980 act deregulated interest rates and overrode all related state regulations.

Deregulated interest rates allow risky lenders to attract deposits by paying more than their competitors. But because these deposits were insured, depositors were shielded from the risks. The insurance created the opportunity for the insolvent “zombie thrifts” to use their new deposits to make even riskier investments. Absent proper supervision, the interest rate deregulation increased the moral hazard of federal deposit insurance. At the same time, deregulated lenders had incentives to make loans at high interest rates to risky borrowers. Consequently, home mortgage providers had more in common with payday lenders than they did with the conservative institutions of the era of interest rate regulation.

The reregulation of interest rates is not a popular idea, but rate ceilings and usury laws may serve two important economic purposes. First, these regulations promote credit rationing when low-income, high-risk borrowers simply do not participate in the home mortgage market. Of course, this rationing may hurt the poor, but there are far better policy responses to poverty than promoting credit and debt. Second, as economists Edward Glaeser and Jose Scheinkman have pointed out, interest rate ceilings and usury laws represent a form of social insurance for the poor. If the demand of the poor for loans increases in an unregulated market, interest rates increase as the poor compete against each other for loans. Usury laws limit this competition and put a brake on high interest rates.28 The motivation for deregulating interest rates under President Carter was more of a matter of helping an industry than of carefully thinking through the implications for consumer welfare. The legislation likely increased risk in the S&L industry. As in the S&L crisis, risky investment of federally insured deposits was central to the crisis of 2008. The 1980 legislation was a first step down the road to the subprime crisis.

As the S&L crisis grew, the thrifts (and other lenders) received new opportunities in the Garn–St. Germain Act of 1982. Perhaps the biggest one with respect to the bubble of 2008 was the new power for financial institutions to make adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). In principle, ARMs are win-wins. An indexed mortgage removes the risk that the lender will end up paying more on deposits that it receives from long-term loans—the so called interest-rate mismatch. A borrower willing to accept the risk of rising interest rates receives a lower expected interest rate over the duration of the mortgage.

But because there has been little regulation and supervision of adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) contracts, lenders have devised a dizzying array of complex mortgage products. Much of the razzle-dazzle in ARM contracts seems designed more to confuse unsophisticated borrowers than to perfect a risk-sharing arrangement. For example, many ARMs locked in low “teaser” rates for two or three years before adjusting to a much higher rate. These teasers might be attractive for professionals who are “sure” that their salary will increase over time; they also make sense for strategic buyers intent on flipping houses in a rising market—at least until the market crashes. But they make little sense for unsophisticated borrowers unable to deal with the long-term consequences of such a loan contract. The same could be said for the so-called pick-a-payment loans innovated by Golden West. Moreover, by the 1990s, it became apparent that some lenders were simply defrauding borrowers by incorrectly applying the adjustments.

Teaser loans were certainly not the only toxin in mortgages in the bubble caldron. Loans were made without income or asset verification. Loans were also made with insufficient down payments so that loan-to-value ratios were too high to prevent strategic default when housing prices declined.29 But the teaser aspect of low or no interest payments initially suckered some people into buying homes. Without the more exotic ARMs, much of the damage of the subprime crisis could have been avoided.

Although the increasing complexity of mortgage contracts may be the change of the 1980s that had the greatest impact on the bubble, other changes contributed to the regulatory climate of the bubble:

1. In order to pretend that the S&Ls were solvent and keep the whole mess off budget, accounting standards for the industry were loosened.

2. So that they could “gamble for resurrection” the S&Ls were allowed to make investments outside of their traditional business of home mortgages. By the end of the 1980s, it was “anything goes.”

3. Private sector participation in mortgage-backed securities was encouraged. State regulation of these securities was preempted.30

4. When the government finally dealt with the S&L crisis by passing the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) of 1989, it created a regulator that turned out to be extraordinarily weak, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS). Washington Mutual, IndyMac, and AIG were able to dodge regulation by the Federal Reserve by choosing the OTS as their regulator.

The deregulatory, nonpunitive climate of the S&L crisis and its aftermath continued with the governmental response to the accounting scandals of the early years of the new century. Although Enron’s accounting firm Arthur Andersen was bankrupted and forced out of business, the other four major accounting firms, far from blameless in those scandals, became too big to fail. The legislative response, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, was weak. Sarbanes-Oxley was not motivated by problems in the financial sector, as the biggest scandals involved Enron, WorldCom, and other nonfinancial firms. Still, legislators might have imposed tighter standards for corporations, including those in financial services. Enron’s problems were related to hiding losses in off-balance-sheet “special purpose entities.” Similarly, in the bubble, banks invented off-balance-sheet vehicles that created leverage without violating the Basel I capital requirements. Wall Street innovated; Washington acquiesced.

In addition to deregulation, financial innovation was central to the crisis. The problems in the home mortgage market would not have produced a crisis bubble without important changes in how these loans were securitized. The innovations involved the development of three new products: privately issued mortgage-backed securities, the tranching of the securities, and the swaps market that insured the securities. But perhaps the most important innovation involved the extent to which these investments were leveraged. In other countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, securitization of mortgages comes in the form of covered bonds. Unlike the securitization that took place in the United States, the issuers of covered bonds are required to post sufficient capital to cover losses on the underlying mortgages. Moreover, in case of default, investors have a general claim on the issuing bank and can seize the underlying mortgages.31

Before we discuss these innovations in detail, it is important to stress that they owe as much to the interaction of ideology, interests, and institutions as they do to the cleverness of the Wall Street quants. In chapter 3 we discussed how campaign contributions from the financial services industry, particularly the sectors concerned with the new products, increased dramatically in the decade of the bubble. We noted that the Democrats have become dependent on the money wing of the party. We also showed that the purveyors of risky financial products were particularly active in lobbying. When Bill Clinton, Bob Rubin, and Larry Summers prevented Brooksley Born from regulating derivatives, they were reflecting some mixture of faith in the self-regulatory framework of free market conservatism and support of their allies on Wall Street. All three did well financially after the Clinton administration—the latter two directly on Wall Street.

The derivatives that led to the bubble were in part fed by predatory mortgage lending. Some states—even a mostly red state, North Carolina—moved to regulate mortgage lending. But by 2005, forces were moving in opposite directions within Congress. Republican Bob Ney and Democrat Paul Kanjorski introduced a bill to preempt all state predatory lending laws, and Democrat Brad Miller made a proposal that would essentially impose North Carolina’s tough standard nationally. Gridlock blocked the passage of both bills. The Miller Bill was one of sixteen congressional efforts between 2000 and 2006 to curb predatory lending; none made it into law. Lobbying, especially by risky lenders, ensured that the institutional hurdles were formidable.32

In an age when Wall Street could safely assume that Washington would be incapable of further regulation, new financial products proliferated. Indeed, with weak reactions to each warning signal—LTCM, Enron, WorldCom, Amaranth, the Orange County bankruptcy—Wall Street saw a green light for financial “development.”

Lewis Ranieri is credited with the invention of the private mortgage-backed security, first issued by Salomon Brothers and Bank of America in 1977. At the time of the innovation, the product was a legal investment in only fifteen states.33 With successful lobbying the innovation went viral at the beginning of the new century.

When investors buy a private mortgage-backed security, they want some assurance of the quality of the underlying investments. But there are at least three channels for misrepresentation in a deregulated market. First, if the originators of the mortgages have no obligation to “keep skin in the game” by maintaining an interest in the mortgages they underwrite, they have incentives to misrepresent the quality of loans and to present fraudulent loan documents. Second, if the creators of the mortgage securities sell the bonds, they have weak incentives to conduct due diligence on the documents prepared by the originators.34 Third, credit ratings agencies that that are hired to bless the bonds have incentives to keep clients happy and understate the riskiness of the investment.

The problems with a privately issued MBS were compounded when the process of tranching emerged. In 1997, the credit derivatives team at JPMorgan came up with two innovations. First, corporate bonds could be pooled into a security; the security in turn could be cut up into pieces known as tranches. The lowest tranche took the highest risk on defaults of bonds in the portfolio and was last in line for cash flow. That tranche has rights to cash flows but no claim on assets. Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) based on subprime tranches suffered the greatest problems with inaccurate ratings.35 The highest tranche was most protected from a decline in the value of the mortgage security. Thus, the top tranche was viewed as essentially riskless. But to make the investment truly riskless, AIG agreed to issue credit default swaps (CDSs) that insured these investments for a pittance. By 1999, the innovation extended into consumer debt, most notably into mortgage debt. But JPMorgan saw mortgages as riskier than corporate bonds, so the firm barely got into the business of the slicing and dicing of mortgages.36 But others were more than willing to pick up the ball and keep running.

How does Washington handle product innovation in financial markets? Almost not at all, as long as no current laws are violated. And if current laws are inconvenient, lobbying typically gets a fix. This process fits well with free market conservatism. All products are welcome in the marketplace. If people are nuts enough to buy tickets to see Charlie Sheen or products endorsed by “reckless few” members like Roger Clemens and Martha Stewart, de gustibus non est disputandum; the products have little potential to inflict harm. New drugs, however, cannot simply be marketed where consumers have the “freedom to choose.” For drugs there is a complicated approval process that requires testing and strict procedures. And if pseudoephedrine hydrochloride gets remanufactured into crystal meth, sale requirements are toughened. Although many might carp at the specifics of how new product introduction in health care is regulated, few would want to get rid of the process entirely. Product failures can have irreversible consequences. Thalidomide, which led to deformed babies, is not an Apple Newton that had no bite. Unfortunately, free market conservatism treats financial products like consumer electronics rather than like drugs.

Worse, whatever regulation existed with regard to derivatives was largely eliminated by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) of 2000. And worst, the CFMA favored derivative owners over debt holders in bankruptcy. Speculative investment bankers had higher priority than bondholders. After Bill Clinton put his signature on this bill and on the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, the frenzy of the Bush years followed. A recent Dallas Federal Reserve working paper shows that the markets in nonprime residential mortgage-backed securities and in credit default swaps soared after passage of the CFMA.37

While Washington was deregulating the derivatives that were fundamental to the bubble, Congress also passed some minor measures that facilitated mortgage origination. The American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act of 2000—directed at easing financing of mortgages, including reverse mortgages, and at increasing financial assistance for homeownership by the poor, elderly, and disabled—was passed by voice vote in the House and unanimous consent in the Senate. The American Dream Downpayment Act of 2003 was passed by unanimous consent in the Senate and without objection in the House.38 It was enthusiastically signed into law by President Bush as a measure that would build the “ownership society” by providing “$200 million per year in down payment assistance to at least 40,000 low-income families.”39 In an era of polarized politics, egalitarians and free market conservatives could come together at least over housing.

The budgetary implications of these overhyped pieces of legislation were minimal. The Congressional Budget Office estimated the net budgetary costs of the 2000 act at under $100 million.40 Although the 2003 legislation authorized $200 million annually in down payment assistance, the most Congress ever appropriated was $87 million in 2004. By 2008, the appropriation was down to $10 million.41 What Washington was prepared to spend on homes for the poor was a pittance compared to what Goldman Sachs and John Paulson were to make by the former’s promoting and the latter’s shorting the Abacus CDO based on residential MBSs. Both “American” acts relaxed standards for lenders and they provided a bit more hot air for bubble products.

The development of new products was largely facilitated by the introduction of computer technology and the Internet to financial markets. When Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) collapsed in 1998, the New York Fed found it necessary to intervene because of potential systemic risk. The business model pursued by LTCM required mathematical models and trading strategies that would have been infeasible without high-speed computing. The “flash crash” of May 2010 was caused by high-frequency trading strategies that high-speed computing made possible. Yet government permitted such strategies to be used without vetting them, and as SEC chair Mary Schapiro has acknowledged, the government did not even have the ability to get a quick grasp on what happened.

The Internet and high-speed computing also contribute to the globalization of finance. A substantial chunk of the bailout money for AIG ultimately landed in foreign banks, including Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse, Barclays, and UBS. That is, the systemic risk initiated by subprime mortgage products extended to the global economy and not just the United States. The implications of globalization for U.S. markets have generally led to political arguments that regulation must be relaxed or business activity will relocate abroad. Arguments that the United States would one day bail out foreign banks were hard to find.

Concentration and Regulatory Retrenchment

Systemic risk is also heightened when a few large financial firms dominate markets. Regulators paid little attention when the nation’s largest insurance company, AIG, came to dominate the credit default swap market. Commercial banks became larger and larger by acquiring risky assets, Countrywide in the case of Bank of America and Golden West in the case of Wachovia. Consolidation was facilitated both by free market conservative opposition to government intervention and by its antitax sentiment limiting the government’s ability to shut down failing banks. In 2005, Global Finance listed eight American banks among the fifty largest in the world: Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Wachovia, Wells Fargo, and Lehman Brothers. By 2009, three of the eight no longer existed. Wachovia was the fourth largest commercial bank in the United States in 2005. The sixth largest, Washington Mutual, is also gone.

Concentration made it more likely that the failure of one or more of the mega-institutions would cripple the economy. This problem was accentuated by the historical evolution of the mortgage market from one in which a large preponderance of mortgages was held by dispersed, small institutions to one in which mortgages went through the MBS pipeline. Mortgage originators everywhere participated in the national and international markets created by securitization. Based on historical correlations, the mathematical models used to price these securities assumed that geographic variation in real estate prices would be low. But the models failed to consider how the market was fundamentally altered by the securitization assembly lines.

Part of the assembly line was the rating of the securities. The ratings were the product of only three firms: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch. If these agencies all produced biased reports, the bad information would be highly correlated across MBSs, so when one went sour it would be highly likely that others would follow. Moreover, even though securitization was predicated on the notion of diversifying risk across mortgages, the end result was to create millions of CDOs that were not only correlated but nearly statistically equivalent. So any firm that invested in large numbers of mortgage-backed securities was concentrating, rather than diversifying, its risk.

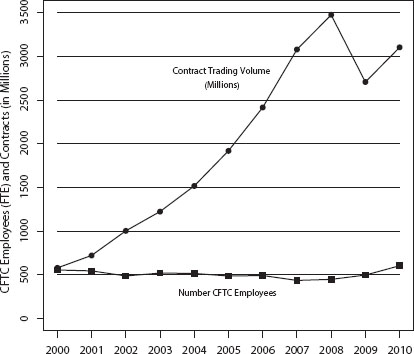

As the bubble inflated, Washington allowed increased concentration in financial services and failed to control new financial products and new financial market structures. Part of the failure was a sheer lack of regulatory resources. As the new markets grew explosively, regulatory resources failed to keep pace. The pattern appears in the budgets and staffing of the FDIC, the Fed, the SEC, and the CFTC.

Figure 5.3. Growth of volume of futures and options contracts and CFTC full-time equivalent employees. Trading volume in futures and options contract trading expanded rapidly. The CFTC had practically no increase in staff. The figure plots the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) CFTC employees and the number (in millions) of futures and options contracts.

Source: Commodity Futures Trading Commission (2011).

The problem is illustrated by figure 5.3, which we have reproduced from the CFTC’s 2012 budget statement. The CFTC noted that during the bubble, “The agency had shrunk from a staffing level of 567 FTE in 1999 to 437 FTE in FY 2007—a 23 percent decline in staff while during the same period the futures and options markets increased five-fold.”42 This decline reflects both the self-regulatory and antitax beliefs of free market conservatism. The SEC and the CFTC together had about 4,400 employees in 2010, while the FDIC had 7,000. In contrast, the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have more than 25,000 employees. Yet “toxic assets,” the tag applied to the new financial products, proved exceedingly dangerous to the nation’s health. The nation saw the full bore of toxicity only when the bubble popped.

Time line of deregulation of financial markets

| 1978 | Supreme Court deregulates consumer interest rates on credit cards; Maine allows entry of out-of-state banks. Similar laws passed in all states except Hawaii by 1992. |

| 1980 | Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act. Eliminates regulation of interest rates. |

| 1982 | Garn-St. Germain Act. Allows for adjustable rate mortgages and interstate acquisitions of troubled banks. |

| 1983 | Federal Reserve. Bank holding companies allowed to acquire discount securities brokers. |

| 1984 | Secondary Mortgage Market Enhancement Act. Facilitates private issuance of mortgage-backed securities. Preemption of state regulation. |

| 1987, 1989, 1996 | Fed expands securities underwriting capacity of banks. |

| 1989 | FIRREA passed to resolve savings and loan crisis, weak regulatory structure implemented. |

| 1994 | Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994, interstate acquisitions and branching permitted. |

| 1999 | Gramm-Leach-Bliley, Financial Services Modernization Act. Repeals Glass-Steagall separation of investment and commercial banking. |

| 2000 | Commodity Futures Modernization Act. Deregulates derivatives markets. American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act. |

| 2003 | American Dream Downpayment Act. |

| 2004 | SEC allows investment banks to expand leverage. |

| 2005 | Congressional impasse on predatory lending. Republicans seek to eliminate state regulation, Democrats seek stronger regulation. |

Sources: Santomero (2001); Strahan (2002); Atlas (2007).

Time line of minority and low-income housing legislation

| 1977 | Community Reinvestment Act. Bans redlining. Used to increase low-income loans of banks seeking merger approval. |

| 1990 | Cranston-Gonzalez National Affordable Housing Act (the HOME Investment Partnerships Act). |

| 1992 | Housing and Community Development Act—Section VIII: Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act, lowered down-payment requirements. |

| 1996 | Housing Opportunity Program Extension Act of 1996. |

| 2000 | American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act. |

| 2003 | American Dream Downpayment Act. |

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Affordable Housing,” http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/affordablehousing/; authors’ notes.