The Pop of 2008

Introduction

We have seen that, historically, responses to pops have been limited and delayed. This pattern continued in the recent crisis. Housing prices began to slide in 2006 and market bubbles began popping in 2007 but serious government intervention through legislation was delayed until American International Group (AIG) collapsed the day after Lehman Brothers fell in September 2008. In April of that year Treasury officials Neel Kashkari and Phillip Swagel had developed a plan to recapitalize the banks in the event of a meltdown.1 Before AIG collapsed, giving the force of legislation to such a plan was unthinkable. Congress was populated not only by free market conservatives but also by liberals opposed to any sort of Wall Street bailout, especially one proposed by a Republican administration. After AIG’s collapse, the plan became imperative. It was taken off the shelf and turned into the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Regulatory reform of the financial system was delayed until after a partisan transition in power.

Even after the transition, the administration of President Barack Obama gave several indications that any change in financial regulation would be limited. The administration likely was cautious so as to reassure financial markets. Despite the passage of TARP in September 2008, markets were edgy well into the first months of the new administration. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, still over 9000 at the beginning of 2009, plunged as low as 6600 in early March. Whether to assure markets, to appease the “Money Wing,” or because of ideological sympathies, the Obama administration restored the ancien régime, former officials who had presided over deregulation and previous bailouts in the administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s. Former Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers was brought into the White House; Timothy Geithner became Treasury secretary. Geithner had been Summers’s undersecretary, and then, as New York Federal Reserve president, he participated in organizing the Bear Stearns takeover, the AIG bailout, and other responses of the administration of George W. Bush to the near collapse of the financial system in 2008. Summers and Geithner were protégés of Clinton’s first Treasury secretary and Citigroup vice chair Robert Rubin, as was Peter Orszag, who became head of the Office of Management and Budget.2 Obama’s team deserves credit for stabilizing the markets. Stress tests were imposed on nineteen large banks. The tests, conducted with rigor, indicated better than expected health. The results most likely made an important contribution to recovery in the financial markets. At the same time, the presence of the team undoubtedly signaled that no major structural change was planned.

Figure 7.1. The ancien régime. Former Clinton economic advisor Gene Sperling and Robert Rubin—dynasty members Peter Orszag, Tim Geithner, and Larry Summers at the White House, February 9, 2009. Source: Official White House photo by Pete Souza.

President Obama’s political ties to figures in the financial sector did not suggest that the administration would discipline individuals and firms whose behavior had been inappropriate. During the 2008 campaign, Obama appointed James Johnson, a former Fannie Mae CEO and currently a member of the board at Goldman Sachs, as head of his vice presidential selection team. After the election, in the summer of 2009, Obama allowed himself to be photographed playing golf on Martha’s Vineyard with UBS North America CEO Robert Wolf, a major fundraiser. UBS had received billions in funds through the AIG rescue after paying a $780 million fine for providing hidden bank accounts to thousands of Americans. Obama also appointed Steven Rattner, a partner in the investment firm Quadrangle Group, to preside over the auto industry bailout. Rattner was later forced out of Quadrangle as a result of a scandal involving the New York State Common Retirement Fund. Rattner also agreed to pay a civil fine and to be barred from the securities industry for two years.

We stress Obama’s ties to the financial sector and his chosen advisers not to question the competence or expert knowledge or contacts of these people. We suggest only that Obama failed to promote the high ethical standards and fundamental reform of financial markets that he promised during his presidential campaign. His calculation was that replacing the “reckless few” with some semireckless savvy would reassure Wall Street.

The Obama administration also signaled policy preferences inconsistent with substantial reform. In March 2009, Obama continued the Bush administration’s support of the big banks in Cuomo v. Clearing House.3 This position placed the administration in opposition to the four liberal justices on the Court, consumer organizations, and the former Democratic attorney general of New York, Eliot Spitzer, and his successor, Andrew Cuomo. The administration initially sided with Wall Street by opposing the Volcker Rule until pressure from congressional Democrats made that position untenable. Finally, the administration kept its distance from reform advocate Elizabeth Warren, whom Congress had charged with oversight of TARP. Again under pressure from congressional Democrats, the administration did give Warren the lead in setting up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that was established by the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, better known as the Dodd-Frank Bill after its primary authors, Connecticut Senator Christopher Dodd and Massachusetts Representative Barney Frank.

Figure 7.2. Economic reform. Elizabeth Warren, Barack Obama, and Timothy Geithner at the White House. This appears to be the only White House website photo of Ms. Warren. Source: Official White House photo by Pete Souza.

Dodd-Frank was the main piece of regulatory legislation responding to the pop. President Obama signed the bill into law on July 21, 2010, well over two years after the Federal Reserve was forced to finance the sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase, and nearly two years after Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed in government conservatorship. Even though the legislation was thousands of pages long, Dodd-Frank left much to rule making by federal agencies, introducing even further delays. Many of these rules are yet to be promulgated (as of this writing at the end of 2012).

Rules on credit risk retention are an example of the delay. Only on March 28, 2011, did agencies announce initial regulations for how much “skin in the game” mortgage originators and securitizers would be required to retain.4 The regulations will not become final until after a period for public comment—where, of course, the “public” means financial industry lobbyists. A final rule is not expected until 2013; it would be effective only one year later. This pattern of delay appears endemic. A report from the law firm Davis Polk indicates that as of June 1, 2012, regulators had missed statutory deadlines on 67 percent of the required rules under Dodd-Frank.5

The final disposition of Fannie and Freddie will be even more delayed. The fate of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) was not dealt with by Dodd-Frank and remains undecided at the end of 2012.

The delay in financial reform reflects, as has historically been the case, partisan politics. Dodd-Frank was passed after two sets of elections, in 2006 and 2008, moved the United States from unified Republican control of the executive and legislature to unified Democratic control. Dodd-Frank undoubtedly is quite different from what would have resulted if the Republicans had retained power. The best evidence for this counterfactual scenario is the eagerness of House Republicans to undo parts of Dodd-Frank after regaining control in the 2010 midterm elections. As a corollary, Wall Street has largely shifted its support away from Barack Obama and toward Mitt Romney for the 2012 presidential election. Pressure to undo the reform is present even though Dodd-Frank was limited.

Reforms were limited by giving regulators extensive rule-making authority. Regulators will be under considerable pressure from the industry (and the Republican House of Representatives) to accommodate Wall Street interests. Consider again the example of “skin in the game” rules for mortgage originators and securitizers. In the March 2011 proposed rule, financial institutions would not be required to retain a share of all mortgages and would be permitted considerable flexibility in how they meet the requirement for other mortgages. Another example of lax implementation of Dodd-Frank is Treasury Secretary Geithner’s decision to remove foreign exchange swaps from clearing and exchange requirements that Dodd-Frank imposed on other derivatives contracts.6 An ideal reform would have limited the scope of regulator discretion in order to stem the inevitable drift toward outcomes preferred by Wall Street. But such a bill was unobtainable because the Democrats lacked a filibuster-proof majority in the 111th Senate. Moreover, several Democrats, such as Senator Ben Nelson of Nebraska, could hardly be classified as “progressives.” On critical amendments, ten or more moderate Democrats often peeled off from the progressives and voted with the Republicans.

Two other limits to the government’s response to the financial crisis are as important as the limitations of Dodd-Frank. First, as just mentioned, the future of the giant GSEs Fannie and Freddie remains up in the air. Second, little has been done to stem the tide of mortgage foreclosures.

Congress passed a mortgage modification bill, the American Housing Rescue and Foreclosure Prevention Act (AHRFPA) in 2008. Because AHRFPA relied on private sector participation and did little to change private incentives, it was ineffective. Then in February 2009, the president announced the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP). This effort, as outlined by former TARP inspector general Neil Barofsky, has also been ineffective.7 By the end of 2011, in a nation in which two-thirds of 117 million households own homes, only 600,000 mortgages had been renegotiated through a government-sponsored program.

The low number of renegotiated mortgages is hardly surprising; HAMP relied on the same private financial intermediaries that sought profits through subprime mortgages and their derivatives.8 In refinancing, these lenders may have the benefit of lowering the probability of default, but hampering the refinancing allows the holder of the mortgage to continue to receive payments at higher interest rates than would be paid in a restructured mortgage. The government accommodated lenders by signing watered-down consent agreements with mortgage servicers on foreclosures and loan modifications.9 As of April 2011 6.7 million homes had been foreclosed, and another 3.3 million foreclosures were expected through 2012.10 Another version of the program, the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP 2.0), finally appears to have led to increased restructuring in the first quarter of 2012.11 But by the summer of 2012, foreclosures began to rise again after legal uncertainties were resolved by a legal settlement between banks and state attorneys general over mortgage abuses.12 Foreclosures are a primary factor in the drop in homeownership shown in figure 5.1.

Ideology Remained Unchanged in the Pop

Despite the shortcomings of Dodd-Frank and other policy initiatives undertaken by the Obama White House and the Democratic-controlled Congress, the shift to unified government was an important factor in the response to the pop. As we document below, this power shift was far more important than any shift in ideology at the level of individual politicians. Things changed because of electoral victories, not because of a change in the beliefs of legislators. Few, if any members of Congress, expressed a change in conviction about free market conservatism similar to that of Richard Posner, chief judge of the Seventh Court of Appeals and faculty member at the University of Chicago Law School,13 or even as much as Alan Greenspan, who testified to Congress that he had been misled by his ideology (see chapter 2).

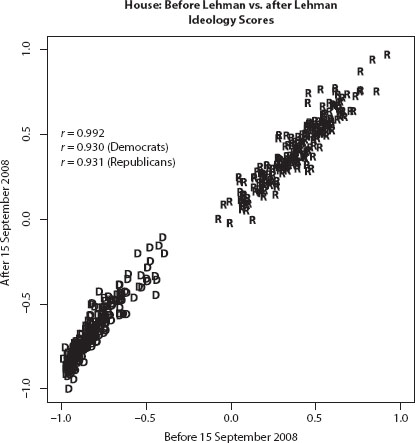

To document the ideological stability in Congress, we compute two new sets of ideology scores to capture a shift induced by the financial crisis.14 The two scores are fully independent measures of ideology. The first set is based on all roll call votes in the 110th Congress before September 15, 2008, the date of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy. The second set is based on the remaining roll calls in the 110th Congress and all roll calls in the 111th, which passed Dodd-Frank in 2010.15 Figure 7.3 displays the results as scatter plots. Each legislator is described by a token, with D for Democrats and R for Republicans.16 The horizontal axis in the figure captures ideology before the date of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy; the vertical, after that bankruptcy.

In the House there is no indication of important change. The tokens pretty much sit on a line. If the pre-Lehman and post-Lehman scores were unrelated, the correlation would be 0. If they sat perfectly on a line, the correlation would be 1.0. The actual correlation is 0.99. Even within each party, the correlations are greater than 0.92. In other words, Republicans did not change their liberal-conservative positions relative to one another. Neither did Democrats.

The Senate story is the same, except for a lower correlation for Democrats. This looser relationship is due in large part to the aberrant behavior of Russ Feingold, whose estimated position moved from that of a very liberal to that of a moderate member of the Democratic delegation. Feingold’s move partly reflects his vote against the Dodd-Frank Bill. Without Feingold, the correlation increased from 0.74 to 0.79. Some of the discrepancy arose because the Senate scores are based on far fewer votes (641 before Lehman and 712 after) than those for the House (1,765 and 1,747, respectively).

That we did not find a major reordering of positions pre- and post-Lehman suggests that the financial crisis and high unemployment did not dramatically change the degree to which free market conservatism is internalized in Congress. This is especially true of the Republicans. Of course, it is technically possible that financial regulation’s mapping onto ideology changed. Perhaps all the legislators moved to the left—away from pure free market conservatism. This is very unlikely, though, given the 2011 efforts of House Republicans to undo major portions of Dodd-Frank.

The stability shown in figure 7.3, moreover, masks important political changes, as it is based only on legislators who served in both the 110th and 111th Congresses. When the Democrats gained in the 2008 elections, free market conservatives did not exit to be replaced by liberals of the Ted Kennedy and Russ Feingold stripe. On the contrary, the Democrats gained by recruiting moderate candidates to run in constituencies that were more “purple” than “blue.”

Figure 7.3. Ideology scores before and after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Each token represents a member of Congress. Each token plots the member’s pre- and post-Lehman ideological score. The points fall nearly on a line, indicating that the financial crisis did not change the ideological alignment in either chamber.

In contrast, when the Republicans gained in the 2010 elections, the party moved in a sharply conservative direction. For example, Pat Toomey, a staunch proponent of free market conservatism and a former president of the Club for Growth, replaced Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter, a moderate whose support was important to the passage of both the stimulus package and Dodd-Frank. Perversely, free market conservatism has been strengthened by the financial crisis and the ensuing recession. Ideology, as figure 7.3 shows, exhibited no reordering at the individual level.

Our conclusion that beliefs did not change is buttressed by studying two votes on a proposal by Brad Miller (D-NC) to regulate predatory lending. The first vote took place in 2007 (pre-Lehman), the second in 2009 (post-Lehman). We discuss the legislation in more detail later in this chapter. The natural experiment that we focus on here is that the Miller Bill (see chapter 5) was essentially the same in both years. Because predatory lending was identified as a major source of subprime mortgages, one might expect a strong shift in favor of the bill. In fact, there was almost no shift; the cutting points (a concept described in chapter 2) are statistically indistinguishable.17 All Democrats supported the bill on both votes, as did a number of moderate Republicans. Extremely conservative Republicans opposed the bill both times. What switching occurred took place in the ideological middle of House Republicans. There were 23 switchers among the 132 Republicans who voted both in 2007 and 2009, but there was a net increase of only 5 Republican votes in favor. The overall increase in votes for the Miller Bill occurred because the Democrats had a large increase in seats as a result of the 2008 elections. The pop of 2008 did not persuade Republicans that predatory lending needed regulation.

Congress as a whole failed to move in a direction strongly favoring increased government regulation of markets. Neither did President Obama. Therefore, in our discussion of the policy response to the pop, we are justified in focusing on electoral shifts and the institutional structure of American government and in downplaying the role of any ideological shift.

Legislation after the Pop

The legislative reaction to the pop consisted primarily of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), passed in October 2008; the Economic Recovery Act (the “stimulus package”), passed in February 2009; and the Dodd-Frank Act, passed in July 2010. These three pieces of legislation illustrate the problems of delay, limits, transition, and electoral incentives. In our discussion we make use of the theoretical approach we presented in chapters 2 through 4. That framework focused on one-dimensional liberal-conservative politics in which agenda setters need to obtain the support of actors such as the filibuster and veto pivots.

Candidate Barack Obama campaigned on a model of the legislative process that is quite different from the pivotal politics model. As a candidate, Obama asserted that “Americans of every political stripe were hungry for … a new kind of politics,” one in which reasonable public policy compromises could be worked out with the opposition.18 But polarization precludes that sort of new bipartisan politics. Obama might have been better served by accepting from the get-go that he would never get more than sixty votes in the Senate.19 Broad-based compromises never happened. The pivots ruled.

For both the stimulus package and Dodd-Frank, the pivotal politics model provides a nearly complete accounting of the outcome. The roll call votes on passage nearly perfectly divide liberals and conservatives. In each case the successful Democratic proposal is one that just barely satisfied the filibuster pivot in the Senate. For the stimulus package, the filibuster pivot was Olympia Snowe of Maine. She demanded and received important concessions that trimmed $200 billion from the bill. The death of Edward Kennedy resulted in Scott Brown of Massachusetts becoming the filibuster pivot on Dodd-Frank. Brown also received an important concession—the elimination of a $19 billion tax on banks. The pivotal politics story does poorly in explaining votes on Henry Paulson’s TARP, however. Voting on TARP reflected electoral concerns in the shadow of a failed presidency, blame-game politics, and the proposal going against core elements of Republican ideology, because TARP represented not only government intervention but also government expenditure. We begin by applying the pivotal politics model to the stimulus package and Dodd-Frank and then return to claim that TARP is truly an exception that proves the rule.

Economic Stimulus and Financial Regulation in the 111th Congress

The 111th Congress closely followed the pivotal politics script. The legislative coalitions that passed the administration’s three major pieces of legislation—the stimulus package, health care reform, and financial reform—were all of minimal winning size. That is, they controlled just enough votes to avoid a filibuster in the Senate. Not only were these coalitions of minimal size, they were essentially the same. Nearly the same sixty votes were used to pass the two pieces of legislation related to the financial crisis and the Senate version of the health care bill that was passed before the election of Scott Brown. Not surprisingly, the splits pitted liberals against conservatives. A small deviation from this pattern occurred when Russ Feingold, a very liberal member of the Senate, voted against the Dodd-Frank Bill on the principle that it did not go far enough. But by and large the playbook for the first two years of the Obama presidency was to persuade sixty Senate liberals and moderates to take on forty conservatives. The House of Representatives also divided into liberal and conservative blocs. In that chamber, which has no filibuster, the Democrats held large majorities. A few members could vote out of line without endangering passage of the legislation.

The Mapping of Complex Legislation: An Aside

Before we show how roll call voting on these major bills conformed to the pivotal politics model, we pause to ask how it would be possible to take issues as complex as economic stimulus and financial regulation and shoehorn them into a simple battle along a single liberal-conservative dimension.

Legislation is far from a simple yes-no decision like “credit card late payment fees are limited to a maximum of ten dollars per month,” which might be thought to provoke a liberal-conservative split. Quite the opposite: rhetoric, framing, and manipulation—that is, plain old wheeling and dealing—are important for holding a coalition together. As a result, acts of Congress now are hundreds or thousands of pages long, each sentence representing a bit of persuasion for someone. Not only do we, as citizens, not want to know what is in these rotten sausages, we don’t have the time to know. Coalition maintenance tends to benefit from a lack of transparency.

These lengthy bills clearly involve many dimensions. At first glance, the coalitions that support them might be thought to be unstable. Opponents could tweak a proposal that would buy off a legislator. For example, on the stimulus package, Olympia Snowe demanded and received a large cut in funds that were to be used to preserve jobs for state and local public employees. Could members more liberal than Snowe be led into opposition by a proposal to cut highway construction funding as well? Unlikely. Could they be led into opposition by a proposal to increase the highway construction portion? Not credible. The many components of a bill may in fact stabilize it into a liberal-conservative alignment. Snowe could be brought on board more easily by allowing her to cut a portion of the bill she strongly disliked rather than restricting her to making an across-the-board cut.

The complexity of the bills, moreover, may not arise from additions to the pork barrel. These provisions may be directed at broadening the bill to incorporate the core ideology of the agenda-setting party, thereby helping to define the bill as a liberal-conservative choice. The financial crisis led to the Dodd-Frank Bill. On the financial side, the central issue was certainly how to solve the problem of systemic risk.

Systemic risk is hardly a liberal-conservative issue. Each regulatory piece involves complex regulatory trade-offs. For example, mandates about down payments and loan-to-value may limit risk by making default less likely. The same mandates, however, would exclude lower-income people from the mortgage market. As another example, large financial institutions may well want to know that in the future they can gamble with impunity, but in the larger society neither liberals nor conservatives are gunning for another TARP.

On the one hand, there is a danger of overregulation. How does one deal with systemic risk when building, as was necessary with Dodd-Frank, a coalition of liberals? Building this coalition was very difficult given the complexity of the trade-offs. On the other hand, the core ideological belief of the liberals—egalitarianism—calls for redistribution, especially targeted to ascriptive identities of race, ethnicity, and gender. So it is not surprising that the legislation created a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau with a dedicated budget outside congressional control. It is also not surprising that this is the portion of the bill most contested by the new Republican House majority.

Furthermore, the bill, at the urging of Maxine Waters (D-CA), an African American congresswoman, included the new Offices of Minority and Women Inclusion in regulatory agencies. It also includes provisions aimed at ending human rights violations connected to armed conflict and trade in minerals from the Republic of the Congo. All these provisions likely increased liberal support for the bill as a whole and may well have decreased conservative support.

In summary, lengthy bills may readily induce splits on the liberal-conservative dimension, and making a bill longer may in fact reinforce how well the bill maps onto the dimension.

The Politics of Stimulus: Getting Along with Pivots

Following a noticeable slowdown in the economy at the end of 2007, the Bush administration proposed an economic stimulus package in January 2008. The centerpieces of this proposal were one-time income tax rebate checks and business tax breaks. Although discretionary fiscal policy had long fallen out of favor among conservatives, the focus on tax cutting minimized the break with ideological orthodoxy.

Democrats also supported an expansionary fiscal program, but they did not support the Bush plan’s sole reliance on tax relief. Democratic legislators argued strongly that the package should also include increased spending especially on unemployment insurance, aid to states, and public works. Leading Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton put forward a plan for $70 billion in spending for housing, heating subsidies, state aid, and $40 billion in tax rebates if conditions worsened. Another point of ideological conflict was the refusal of the administration and Republicans to support rebate checks for workers who did not pay federal income tax, essentially arguing that rebates for non–income tax payers constituted a form of welfare.

In formulating their response to the president’s plan, Democratic leaders faced two problems. First, the 2006 elections that had provided them with their legislative majority also added a large number of fiscal conservatives to their caucus who were more likely to oppose expansions of social spending to stimulate the economy. Second, the leadership was concerned with the party’s fiscal image. The Democratic Party had used the spiraling deficits of the Bush years to put itself forward as a party of fiscal responsibility. This new reputation solidified the support not just of independent voters but of the party’s “money” wing. Consequently, Democratic leaders were wary of getting so far in front of the president that they might once again be branded as big spenders. A further complication was that any stimulus plan would involve the Democratic Congress waiving the “pay as you go” budget rules that they reinstituted when they regained control of Congress.20

So despite important partisan and ideological differences over the structure of a stimulus plan, the House of Representatives quickly passed a $164 billion package that more or less hewed to the Bush administration’s priorities. But the Democratic leadership of the Senate pushed for a much more extensive plan that cost $204 billon, which included extensions of unemployment insurance, subsidies for home heating, and subsidies for the coal mining industry.21 Although the larger measure earned the support of eight Republican senators (including several in tough reelection situations), Democratic leaders failed to obtain cloture and the measure failed.22 The Senate tacked payments to Social Security recipients and disabled veterans onto the House bill and passed the measure 81–16. The House then adopted the Senate version with a vote of 380–34.23 President Bush signed the final $168 billion package.

Although an unusual level of bipartisanship (especially for the House) led to very quick passage of the first stimulus bill, the necessary political expedients minimized its effectiveness. The insistence on rebate checks rather than adjusted tax withholding meant that it took several months for the money to hit the economy.24 Moreover, because the rebates came in the form of income tax credits rather than offsets to payroll taxes, many low-income Americans (those most likely to spend the refunds) did not receive assistance. The lack of aid to states and support for unemployment extensions also allowed the financial situation of states and the unemployed to deteriorate. Moreover, the polarized debate over making the Bush tax cuts permanent precluded discussions of any durable changes in tax law that might have had stronger economic effects.25

The bill heralded the end of bipartisan cooperation on fiscal stimulus. As the 2008 elections approached, Democrats increasingly called for a second round of stimulus, which Republicans were just as adamant in resisting. The shape of the next fiscal program would be delayed, to be determined by the presidential and congressional elections that fall. The partisan debate followed the traditional ideological pattern: John McCain and the Republicans argued that any future stimulus ought to focus on personal and business income tax cuts (by making the Bush-era tax cuts permanent) while Barack Obama and the Democrats argued for more spending targeted toward those of low income, the unemployed, and struggling homeowners. The Democrats also stressed the need to boost infrastructure spending by funding “shovel-ready projects.”

After Obama won the election in November 2008, many thought that he might encourage a lame duck congressional session to pass stimulus measures. But it was determined that any such measures might be limited by opposition from President Bush. Consequently, stimulus legislation was further delayed until the new Congress convened in January, with the expectation that passage would not occur until after the inauguration.26

While candidate Obama campaigned on behalf of a $175 billion stimulus plan, spiraling job losses and cuts in production suggested that a much more expensive package would be necessary. By the end of November, Democratic leaders were pushing for a package closer to $300 billion. By December, the target number had reached $600 billion. Some economists, both Democrat and Republican, argued that the package should be twice that large.

Several factors complicated the formulation of the 2009 stimulus package, formally designated the American Recovery and Investment Act. The first is that the urgency of the situation and the exigencies of a presidential transition (much of the economic team was not yet in place) meant that the administration would have to defer to Congress on many of the details in the package. This opened the door to funding many congressional pet projects that were hard to justify on purely macroeconomic grounds.27

In some sense, the loading up of pork was unavoidable. Most economists were pushing for a very large number, and the money had to be spent on something. This outcome, however, helped foster an image of the new administration as fiscally undisciplined. That Republicans were able to exploit this image undermined any hopes of the Obama administration for a bipartisan pact. Cross-party cooperation was considered important both because Obama had promised to foster a postpartisan environment in Washington and because it would have better insulated him against charges of pursuing a left-wing agenda.

By January, the size of the proposed package had reached $775 billion. It grew to $825 billion by the end of the month. But it remained much smaller than what even some Republican economists were advocating. (This advocacy had little effect on Republican politicians, however.) Moreover, fissures within the Democratic Party emerged over the size of the tax cut provisions relative to social spending and investment in infrastructure.28 For their part, the Republicans began to attack the program as too large and too light on tax cuts. Concerns about deficits and debt began to be expressed openly by both Republicans and moderate Democrats.

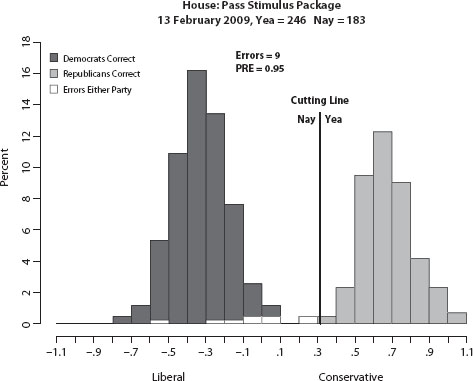

The two houses of Congress approved the conference report on the stimulus package on February 13, 2009. We begin with the House vote, shown in figure 7.4. Because the House operates by majority rule without a filibuster, 255 Democrats, in a chamber of 435 members, had a relatively easy time passing legislation in the lower house. The conference report was approved by a lopsided vote of 246 to 183.29

Figure 7.4. The House and Senate votes on the conference report for the Stimulus Package. In the Senate vote, the single prediction error represents Voinovich (R-OH).

The vote went strict along party lines with the exception of seven Democrats who voted against the stimulus package.30 None of the seven—Bobby Bright (AL), Peter DeFazio (OR), Parker Griffith (AL), Walt Minnick (ID), Collin Peterson (MN), Heath Shuler (NC), and Gene Taylor (MS)—held a safe seat. Four were defeated for reelection in 2010; the other three obtained 55 percent of the vote or less. With one exception, DeFazio, all seven had ideological positions close to the vote’s cutting line. In other words, they were estimated to be nearly indifferent on the issue. One may have already been tilting conservative. In September 2009, Parker Griffith of Alabama continued a pattern, started by Strom Thurmond, of Southern Democrats switching to the Republican Party. When Griffith switched parties his DW-NOMINATE score jumped all the way from moderate center to conservative (the numerical change was from –0.01 to +0.54). Griffith was far from pivotal. Party discipline was not necessary to bring him or other defectors into line.

The Senate vote on the stimulus package conference report, shown in figure 7.4, is a different story. To get to sixty votes, the administration needed all fifty-six voting Democrats as well as Bernie Sanders, the Independent. (Ted Kennedy was too ill to vote, and Minnesota’s Al Franken had not yet been seated following a contested election.) The administration also needed three votes from Republicans. It got the votes of the three who are by our estimates the most liberal—Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins of Maine and Arlen Specter (who later switched to the Democratic Party) of Pennsylvania.31 The result was a minimal winning coalition that fit perfectly onto a one-dimensional liberal-conservative map. The vote is shown in figure 7.4. The only prediction error is that of George Voinovich (R-OH), whose ideological score was to the right of Specter’s but is statistically indistinguishable. The Democrats did obtain the votes of the three most moderate Republicans. Voinovich’s vote against the stimulus package represents a small error for our statistical model.32

How were these sixty votes cobbled together? Media attention focused on Senator Snowe’s demand for a $200 billion reduction in the package in exchange for her vote. One suspects that many other supporters had their demands met, with the result that more than three thousand changes were made to the bill between initial House passage and final enactment. Each one of these changes contained a little bonbon for someone. The vote turns out to be liberal-conservative simply because fewer bonbons were needed for liberals than for conservatives.

Upon signing the $787 billion bill, President Obama did not rule out a second stimulus package.33 But public support for the package was never very strong. At the time of passage, a bare majority supported it.34 But strong majorities felt that tax cuts rather than spending increases were the most effective part of the package.35

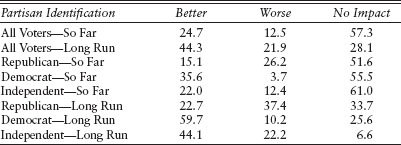

When joblessness failed to decline, not only did the Recovery Act decline in popularity but voters increasingly split on partisan lines. Most important, independent voters who had been crucial to Obama’s election began to accept the Republican narrative that the stimulus package had harmed the economy. Table 7.1 provides partisan breakdowns for two questions asked in July 2009:

So far, do you think the government’s stimulus package has made the economy better, made the economy worse, or has it had no impact on the economy so far?

Voter attitudes about the impact of the Obama stimulus plan on the economy as of July 2009

In the long run, do you think the government’s stimulus package will make the economy better, will make the economy worse, or will it have no impact on the economy in the long run?

The polls also found that 65 percent of the public opposed a new stimulus package, and strong majorities prioritized deficit reduction.36 When public opinion turned against additional stimulus, it became more difficult to sell a new package to moderate Democrats. Those facing tough reelection contest in 2010 were especially reluctant to support more spending.37 Consequently, the administration rejected calls from the left for a second round of fiscal expansion.

Some individual elements of the stimulus package were modestly popular with voters—especially the extension of unemployment benefits. So the administration strategy shifted from a focus on macroeconomic stimulus to targeted social and infrastructure spending as well as tax breaks designed to subsidize job creation.38 But even these more modest approaches were contentious. Republicans filibustered a bill to extend unemployment benefits for several weeks. The bill passed only when newly elected moderate Republican Scott Brown switched his vote in favor.

Assessing the extent to which ideology and polarization inhibited the U.S. fiscal response is somewhat complicated. The United States did have one of the largest discretionary stimulus bills among developed economies.39 This does not mean that the highly polarized U.S. political environment had no impact on the passage of the stimulus bill.

First, because the financial crisis that precipitated the worldwide recession was focused on the United States, one would expect the need for a compensatory fiscal response to be higher, ceteris paribus. Second, although political constraints were important in the United States, economic and financial ones were less so. The status of the dollar as the international reserve currency and the flight to the security of U.S. treasuries during the crisis made deficit spending much cheaper in the United States. The Europeans were more concerned with the impact of spending on the value of their common currency, a concern that continued into 2012 with the government and bank debt crises of Ireland, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. Third, the $787 billion price tag vastly overstates the stimulative effect of the bill. Much of the package was used to offset declines in state and local spending.40

Many provisions in the package would have passed as standalone legislation. For example, 10 percent of the package was an adjustment to the alternative minimum tax, like those Congress has repeatedly made over the past decade. As even President Obama now admits, the infrastructure spending was very delayed in getting into the economy.41 Finally, the size of the U.S. package needed to be larger because it was delayed for several months due to the presidential election and transition. By comparison, most of the other stimulus packages in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries were passed in November 2008.

Ultimately, the size, delay, and composition of the stimulus bill limited its impact. Stanford University economist Robert Hall, affiliated with the generally conservative Hoover Institution think tank, estimates that the stimulus package reduced the shortfall in gross domestic product during the recession by 2 percent, from 10.2 percent to 8.2 percent.42

In summary, the U.S. fiscal response to the crisis was affected in important ways by the ideological and constituency structure of the party system. Although modest bipartisanship was possible at the beginning of the recession, the window for cooperation closed quickly as the crisis deepened and the 2010 election neared. A quick and coherent response was undermined both by the divergent ideological commitments across the parties and divisions within the Democratic Party.

Financial Market Reform

Between passage of the stimulus bill and the Dodd-Frank Bill, Congress passed and the president signed a bill imposing new regulations on the financial services industry. The Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 became law in May 2009. This legislation was low-hanging fruit, proconsumer regulation that had been on the Democrats’ agenda for years.43 Abusive practices, such as repeated penalties for small overdrafts on debit cards, had received widespread attention. The bill passed easily in the House, with only seventy votes against it, all but one coming from Republicans, generally the most conservative members. The bill was then modified and approved in a near unanimous 90–5 vote in the Senate.

One Senate modification, Section 512, put the bill in potential danger when the House took a vote on accepting the Senate bill. Section 512 allowed private individuals to carry weapons on public lands such as national parks. If the Senate bill were voted on as a whole in the House, it might have been killed, with liberals voting against guns and conservatives voting against economic regulation. The House leadership deftly split the Senate bill into two votes. The first, on everything but Section 512, passed with only sixty-four votes against, again all but one coming from Republicans. Then Section 512 was adopted. On this roll call, Democrats cast the vast majority of the negative votes, 145 of 147. Consequently the bill passed, to the delight of both the consumer lobby and the gun lobby. The votes indicated that a liberal-conservative split was likely on the larger issues of financial reform to be addressed in the Dodd-Frank Bill.

The major push on financial reform began in June 2009 when the Obama administration released an eighty-nine-page outline of its reform priorities. The plan focused on four principal areas: the creation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council, which would help coordinate regulatory agencies and provide macroprudential oversight, a modest revamping of the structure of banking regulation, enhancement of the government’s ability to take over and unwind failed financial firms, and the creation of a new regulatory structure for consumer and investor protection. The proposal was immediately attacked from the left and right ends of the ideological spectrum.

The criticism from the left focused on what was missing from the bill. In particular, the administration had not proposed enough to regulate executive compensation practices that many felt were responsible for excessive risk taking. Moreover, the administration’s proposal was seen as having a light touch in regulating derivative and securitization markets. The proposal also did little to reform credit rating agencies whose AAA certifications of subprime securitizations helped trigger the crisis.

Conservatives focused on two other aspects. First, there was general opposition to more regulation, especially in the area of consumer and investor protection. Second, conservatives feared that the creation of a resolution pool for unwinding failed financial firms would perpetuate moral hazard and lead to more government bailouts. This fear was previously manifested in conservative opposition to TARP. One area where the Left and the Right converged was in the criticism of the expanded role of the Federal Reserve, which the Left blamed for ignoring the crisis and the Right blamed for being too quick with bailouts. The convergence, as we show in chapter 8, appeared in the thirty negative votes against Ben Bernanke’s reappointment to a second term as Fed chairman in January 2010.

In the fall of 2009, House and Senate committees began work on legislation. Despite concerns that progressives in the House would try to pull the bill to the left, the bill that emerged from the House Financial Services Committee hewed closely to the administration’s blueprint. When the bill came to the floor, the two most substantial amendments came from Bart Stupak (D-MI), to tighten rules for central clearing of derivative contracts and for securitization.44 These amendments were supported overwhelmingly by the left wing of the Democratic Party and allowed those members to go on the record as supporting much more stringent regulation of Wall Street. Ultimately, House Bill 4173 passed on December 11, 2009, by a margin of 223–203. All Republicans voted against the bill, as did 27 Democrats. As would be expected, the Democratic defectors were heavily concentrated in the moderate wing of the party (as measured by DW-NOMINATE scores). Some liberal members did oppose the bill, claiming it did not go far enough.

The main Senate proposal was unveiled in November 2009. Senate Banking Chairman Chris Dodd proposed sweeping changes in the power of the Federal Reserve to regulate banks. The changes would have given the Fed little role in consumer protection and systemic risk regulation. Consequently, the Dodd proposal was seen as considerably more ambitious than the administration proposal or the House bill. Dodd and his staff probably felt that the bill would appeal to the populist, anti-Fed Republicans.45

But Republican opposition to Dodd’s original plan was substantial. Following Brown’s victory in the special Senate election in Massachusetts, it became clear that some Republican support would be necessary to secure the sixty votes needed for cloture. Consequently, Senator Dodd spent several weeks trying to negotiate with some of the panel’s Republican members in hopes of securing some level of bipartisanship. After negotiations with ranking minority member Richard Shelby (R-AL) collapsed, Dodd engaged Republican senator Robert Corker of Tennessee. The primary sticking point in these negotiations was the structure of the proposed Consumer Financial Protection Agency (CFPA).46 The CFPA’s backers insisted that for the agency to be effective it must be totally independent, with full rule-making and enforcement power. Republican opponents wanted any new powers vested in an existing agency, preferably the Federal Reserve. But these negotiations collapsed.

Senator Dodd unveiled his final plan on March 15, 2009. In many ways, the plan moved much closer to the House bill and scaled back many of its earlier provisions. It adopted some Republican demands in the hopes of ultimately attracting GOP support but it did include the so-called Volcker Rule banning proprietary trading by deposit-taking banks.47 Although such a prescription had been pushed by former Fed chair Paul Volcker, it was not endorsed by the administration until early in 2010. This endorsement was at least in part a response to criticism from the left that the administration’s proposals were toothless.

The Senate version moved in a considerably proregulation direction when a measure backed by Arkansas Democrat Blanche Lincoln was added to the bill. Lincoln’s provision called for the largest commercial banks to spin off their lucrative derivatives trading operations.48 Initially, the proposal engendered opposition not only among Republicans but also within the administration and among Democrats from New York.

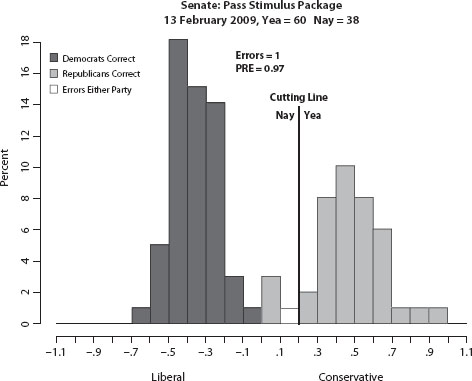

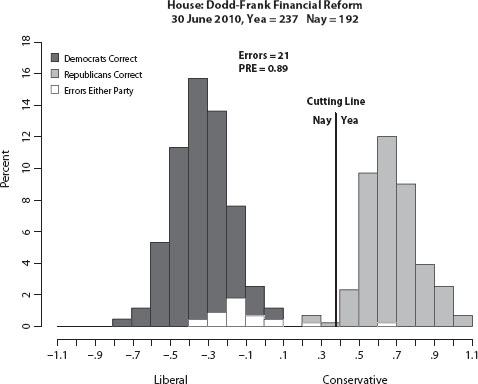

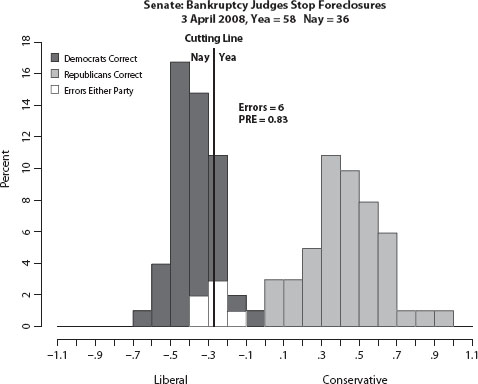

The resulting financial reform bill fit into pivotal politics along the same lines as the economic recovery package, not only in falling along liberal-conservative lines but also in squeaking through with just enough votes on the conference report to beat a Senate filibuster. The House agreed to the conference report on June 30, 2010, by a vote of 237–192. Again, with a large House majority, the Senate was the pivotal chamber. There were, in comparison to the stimulus package, more partisan defections in the House, with 19 Democrats voting against the bill.

The number of prediction errors was twenty-one, including three Republicans who voted in favor (see figure 7.5). Two of these were among the most moderate Republicans, Walter Jones of North Carolina and Joseph Cao of Louisiana.49 The third yea vote came from Michael Castle of Delaware, the second ranking Republican on the House Financial Services committee. Castle was closer to the center of the party.50 His attempt to move on to the Senate was derailed in the Republican 2010 primary by Tea Party candidate Christine O’Donnell. Cao was a freshman representative who had defeated the corruption-tainted William Jefferson in New Orleans. By 2010 Cao’s district returned to its usual status by electing an African American Democrat, so Cao did not return to the House in 2011.

Of the three House Republicans who deviated from free market conservatism and supported Dodd-Frank, two are no longer in Congress. These small changes in representation are part of the larger process of increasing polarization, a process that will also increase the vulnerability of Dodd-Frank if the Republicans ever reassert unified control of the White House and Congress. Castle’s defeat at the hands of the Tea Party was far from Obama’s fantasy about politicians of all stripes engaging in compromise.

The Senate vote on the conference report for the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill paralleled action on the stimulus package. Again the Democrats needed three Republican votes, even though Al Franken had by now been sworn in and Arlen Specter had switched parties. One difficulty the Democrats faced was that Robert Byrd had died, leaving a West Virginia seat vacant.

The Senate vote had four exceptions to a perfect liberal-conservative split. The interesting exception was Russ Feingold of Wisconsin. Feingold’s “error” is shown as the leftmost white block in figure 7.5. Feingold, previously one of the most liberal Democrats, decided to stand on principle and refused to vote for cloture. So a third Republican vote, in the person of Scott Brown, was needed.

As it turns out, there were real consequences to Feingold promoting Brown into the pivot position. One of the provisions to come out of the House-Senate conference was a levy on large financial firms to pay for the costs of financial regulation. This provision was quickly dubbed a “bank tax.” As a result, Brown, who had supported the earlier Senate version, began to waver. The provision not only ran counter to his ideological opposition to anything resembling a tax increase, but would have been costly to large financial firms in Brown’s home state.

Figure 7.5. The conference report votes on the Dodd-Frank Bill. For the Senate, the prediction errors shown represent Feingold to the left and Voinovich, Murkowski, and Lugar in the center. The errors in the center are close to the cutting line, indicating that the senators were nearly indifferent on the bill. Feingold’s error is far more substantial.

In the aftermath of Byrd’s death, a defection by Brown would necessitate picking up the two Democrats who had opposed the original Senate bill, Feingold of Wisconsin and Maria Cantwell of Washington. Cantwell did switch her vote, but Feingold did not, necessitating the removal of the bank tax. This shifted $19 billion in costs from the banks to taxpayers. Feingold performed the legislative equivalent of a liberal voting for Ralph Nader in Florida in the 2000 presidential election: standing on principle only to get an outcome he couldn’t possibly have wanted.51

The other three errors shown in figure 7.5 are trivial exceptions. Republican senators George Voinovich (OH), Lisa Murkowski (AK), and Richard Lugar (IN) voted against the bill when their ideology score called for a vote in favor. Their ideal points are so close to the cutting line that these are very minor errors for the spatial model. The split was, except for a tad of randomness in the center and Feingold’s hiccup on the left, a pure liberal-conservative division.

The 110th Congress: The Passage of TARP

In contrast to the stimulus package and Dodd-Frank, the passage of TARP does not fit into our model of liberal-conservative voting. Why? Several explanations complement each other.

1. In the 110th Congress TARP was an emergency measure that went against the core ideology of the agenda-setting party, the Republicans. The agenda setters were Bush appointees, Treasury secretary Paulson and Fed chair Bernanke. Bernanke, who intensely studied the Great Depression as an academic, almost certainly was motivated to avoid a second collapse of the economy. The bill permitted additional spending of $700 billion, with at least the first $350 billion at the total discretion of Paulson—a slap in the face to free market conservatives. The week before Lehman failed, when Fannie and Freddie were effectively nationalized, “Doctor Doom,” Nouriel Roubini, keying off economist Willem Buiter, wrote of “comrades Bush, Paulson, and Bernanke.”52 The absence of support in core ideology is a factor that led TARP not to fit into the standard pivotal politics story.

2. Presidential leadership was absent; Paulson and Bernanke, not Bush, were the agenda setters. Following Lehman’s collapse and the AIG bailout, Bush’s job approval fell into the low 20s.53 Presidential candidate McCain and Republican congressional candidates were loath to mention Bush’s name. In fact, McCain undercut the White House; following the AIG bailout, he announced that he was suspending his campaign to return to Washington to work on the financial crisis. Two days later, Paulson proposed TARP. Bush’s appeals to congressional Republicans to support TARP in the national interest fell on deaf ears in the context of his failed presidency.

3. With elections only weeks away, legislators in close races feared a populist backlash were they to vote for the bailout.

4. Support for the bailout reflected the local interests of representatives from New York and campaign contributions.

These four factors combined to fracture the usual ideological splits. Before we indicate the nature of this fracture, we will show that, before Lehman, the 110th Congress did vote on financial services matters along ideological lines. Post-TARP, Congress also voted ideologically on the bailout of the auto industry. The force of ideology before and after TARP indicates that the TARP episode was a deviation that arose in dire circumstances, starting with the collapse of the housing market.

The housing market meltdown began in 2006, and Washington was unresponsive to the fall in housing prices. Fed chair Alan Greenspan had indicated that the Fed would not intervene in asset market bubbles. Bush appointed Bernanke to succeed Greenspan near the start of the meltdown. At Bernanke’s Senate confirmation hearing on November 15, 2005, he said what the Republican-controlled Congress wanted to hear: “I will make continuity with the policies and policy strategies of the Greenspan Fed a top priority.”54 In the summer of 2007, a St. Louis Fed document claimed, “The [Bernanke] Fed has been successful in preserving continuity with the Greenspan era.”55 Neither the Fed nor the executive branch nor Congress was eager to address the consequences of the bursting housing bubble.

The Democrats, having won the 2006 midterm elections, were in control of Congress for the first time since 1994. They made some attempt to control the worst practices of the subprime market. In the House, Representative Brad Miller, a North Carolina Democrat, introduced the Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act of 2007.56 Patterned after similar legislation in Miller’s state that had been enacted in 1999, this bill strengthened the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA). By 2007, some thirty states and the District of Columbia had enacted their own legislation. Miller’s bill was aimed at a federal strengthening of consumer protection in the mortgage market. It passed the House on November 15, 2007, by a vote of 291–127, with all Democrats and 64 Republicans in favor. The vote was highly ideological, with the more moderate Republicans joining the Democrats. There were, as shown in figure 2.5, only thirty-two prediction errors, all Republicans close to indifference, as shown by the cutting line. At that time, less than a year before the political pop, the Senate failed to act on a bill. The bill was reintroduced in the 111th Congress and passed, on May 7, 2009, by a vote of 300–114, with only 3 Democrats voting against it. Again, Republican moderates split from conservatives. And again the Senate failed to act. Miller’s bill would eventually become legislation as Title XIV of Dodd-Frank.

The previous antipredatory lending statute was extremely weak. The interest rates and fees that would trigger HOEPA protection were so extreme that they would apply only to 1 percent of subprime loans.57 Presidents of both political parties preempted the more stringent state regulations. In 1996, under Clinton, the Office of Thrift Supervision, that weak regulator created by FIRREA, exempted all federally chartered savings and loans from state regulation. In 2004, under Bush, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) exempted all national banks. Representatives Bob Ney (R-OH) and Paul Kanjorski (D-PA) tried to go one step further in 2005 by introducing a bill that would preempt all state regulation. The bill never made it to the floor, perhaps because Ney got caught up in the Jack Abramoff scandal and eventually served seventeen months in prison.

The Supreme Court, regulators, and legislators also addressed the issue of federal preemption of state regulations. The OCC had fought state level prosecutions of national banks for violating state fair-lending laws. This led to the Cuomo v. Clearing House Supreme Court case discussed earlier in this chapter. In a surprise decision, Justice Antonin Scalia voted with court liberals to strengthen state intervention.58 The role of the states was reinforced only after the pop, not only by the court but also by Dodd-Frank, which set federal regulations in this area, like minimum wages, as a floor rather than a ceiling.

If the predatory lending issue failed to gain political traction before the pop, the fall in housing prices created political pressure in the 110th Congress to provide relief to homeowners who were being forced into foreclosure. Some homeowners engaged in strategic default, but others simply lacked the resources to make their monthly payments, either because they had become unemployed or because their mortgages had reset from a teaser rate to a higher rate or because they had never from the start had enough income to make payments.

Former Treasury official Phillip Swagel observed that there was no spike in mortgage defaults around the reset dates of specific types of adjustable rate mortgages (the so-called 2-28 and 3-27 mortgages.)59 He thus concluded that the problem was the initial lack of income and credit worthiness of the borrowers.60 Some of these borrowers had been led into the loans by shady originators. Regardless, just as Wall Street and the automobile industry expected a bailout, households in foreclosure were looking for government assistance. Many borrowers were in the low-income minority electorate that supported the Democrats.

A limited response to foreclosures finally took place in the summer of 2008. On July 30, President Bush, withdrawing an earlier veto threat, signed the Housing and Economic Recovery Act. The bill is better known by its House title, the American Housing Rescue and Foreclosure Prevention Act (AHRFPA), a measure designed to reduce foreclosures by securing reductions both in the principal amount of a home mortgage and in penalties. Because lender participation in the program was voluntary, the bill packed little punch. The bill also opened a blank check extending credit to Fannie, Freddie, and other federal housing institutions and it contained legislation designed to improve mortgage disclosure and to license mortgage originators.

At the time AHRFPA passed, a foreclosure relief program with sharp government mandates and haircuts imposed on lenders was unthinkable, particularly because President Bush was pivotal. Also unthinkable was that the credit subsidies to the privatized GSEs would be small potatoes in a government takeover of Fannie and Freddie, an event less than two months away.

Because AHRFPA was both pre-Lehman and prior to the 2008 elections, any options were limited to tweaks that were consistent with the free market conservative perspective. Before the financial crisis, the mortgage market was almost entirely privatized. The activity of the government was reduced, as we explained in chapter 5, to subsidizing the private sector off budget. Through the regulatory implementation of the Community Redevelopment Act, the government also pushed private firms into targeting more loans to the poor and minorities. All of these government policies were indirect, and nearly all mortgage contracts were written by for-profit financial intermediaries. Depression Era–style moratoriums or government takeovers of the servicing of these privately held mortgages were off the table. The proposed legislation continued to rely on the private market. Nonetheless, Bush opposed the bill when it was introduced in April.

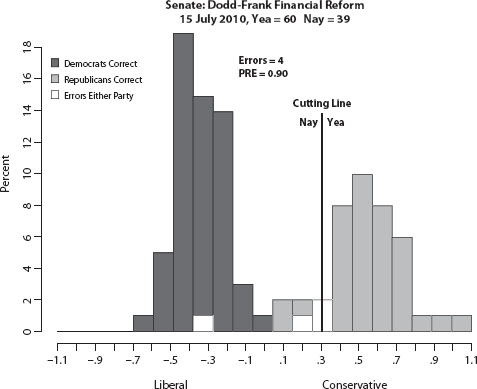

The agenda for foreclosure relief was set by the Democrats, who held majorities in both the House and the Senate. In April 2007, the Senate transformed what originally had been an energy bill, HR 3221, into a foreclosure prevention act. Throughout the legislative process, the Senate always voted for passage by large margins. The bill passed the Senate by an 84–12 vote on April 10. After the amended bill had been returned by the House, the Senate, between June 25 and July 11, acted and returned the bill to the House with votes that were no closer than 79–16. The Senate then passed the final bill by a 72–13 margin and sent it to the president for signature on July 26. In April 2007 Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) had proposed an amendment directed at allowing bankruptcy judges to prevent foreclosure. This measure, which was much more than a tweak on free market conservatism, might have kept many homes from foreclosure, but it was opposed by all Republicans. The amendment was tabled in a 58–36 vote in which 11 Democratic moderates voted with the Republicans (see figure 7.6). The versions of the bill accepted by the Senate, however, always drew large, bipartisan support with limited Republican opposition. Only a minority of Senate Republicans opposed the bill.

Figure 7.6. The Senate vote on the Durbin Amendment to allow bankruptcy judges to block foreclosures. The vote is liberal-conservative, with the errors symmetric about the cutting line. The vote is a further indication that Congress divided ideologically on financial reform before the failure of Lehman Brothers. The vote also indicates that Democrats would not be a solid majority in favor of progressive financial reforms.

The House was far more divided. On May 8, 2007, the House modified the Senate bill to include $300 billion in loan guarantees for lenders willing to renegotiate the principal amount of mortgages. The House modification was met by a veto threat from the president. The modification was approved on a 266–154 vote, with all Democrats voting for the guarantees and the Republicans opposing, 154–39. Atif Mian, Amir Sufi, and Francesco Trebbi have shown that Republican opposition was stronger among conservatives,61 where conservatism is measured by our DW-NOMINATE scores. As indicated above, DW-NOMINATE makes some errors on the AHRFPA vote. Mian, Sufi, and Trebbi explain that Republicans were more likely to support AHRFPA if they were from districts with high foreclosure rates, especially if foreclosure rates were high in Republican parts of the district. Roll call voting by the Democrats showed no sensitivity to foreclosure rates because ideology alone promoted support for mortgage modifications. Republicans were cross-pressured; they had constituents, even Republican constituents, who would benefit from mortgage resets, but a federal program ran against the grain of free market conservatism.

The voting patterns present on the May 2007 vote were repeated on the final vote in the House on July 23. The vote was 272–152, with only 3 Democrats voting against it and only 45 Republicans in favor. When the roll was called, fidelity to free market conservatism dominated. Fewer than one-fourth of House Republicans voted for AHRFPA. (The vote is illustrated in figure 2.6.) Even though it took place less than two months before the fall of Lehman Brothers, the vote remains highly ideological but contains somewhat more error than earlier votes. The increased voting prediction errors relate, as shown by Mian, Sufi, and Trebbi, to increased foreclosure rates in congressional districts. For a few, constituent interests trumped ideology.

In contrast to Obama and the Democrats with the stimulus and Dodd-Frank, George W. Bush was not part of the agenda-setting process on foreclosure legislation. The demand to change the status quo came from the Democrats. A Senate filibuster was not in the cards, perhaps because many constituents in most senators’ states had problems with foreclosure. Because the Democrats were not even close to a veto override majority, the president’s support, not that of the sixtieth senator, was pivotal. Bush appears to have come on board for two reasons. First, between April and July 2008 the housing crisis worsened considerably. Presidents, as well as Republican House members, can be sensitive to foreclosure rates. In September 2008, Fed chair Ben Bernanke was reported to have said, “There are no atheists in foxholes and no ideologues in financial crises.”62 The Republican supporters of AHRFPA are indicative of Bernanke’s claim. Second, as indicated earlier in this chapter, AHRFPA had no bite. The president’s support was largely a symbolic acknowledgment of the foreclosure crisis. Even with the loan guarantees in place, Senate Republicans did not make a fuss and Bush signed the bill. When real money was on the line, as was the case with TARP, Republican ideologues in Congress would not be helpful to Bernanke.

After Bush signed, in a rare sign of media bipartisanship, both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal touted it as the most significant housing legislation since the New Deal. That the elite media failed to see that the legislation would do little about foreclosures is indicative of how uninformed most of the nation was about the impending collapse of Wall Street. By 2011, Washington was still unable to solve the foreclosures problem, in part because of the complexity of securitization and servicing that had doomed the shadow banking system.63 People in homes facing foreclosure are stuck between a rock and a hard place. If banks were to take haircuts and reduce the principal amount of large numbers of mortgages quickly, they would have to take a huge accounting hit, which would reveal that they were badly wounded paper tigers. Foreclosing in dribs and drabs spreads out the accounting losses. If the government were to pay for a haircut it would have to raise the revenue or increase the deficit. In chapter 8 we show that bailing out homeowners had become politically unthinkable.

Although the pop of financial markets is often identified as the Panic of 2007,64 the political pop—delayed, of course—occurred only in September 2008. The pop resulted in the rather chaotic voting on TARP, which we discuss below. To complete our story of the force of ideology in the 110th Congress, however, we first jump to the bailout of the automobile industry. This episode shows how quickly the standard liberal-conservative conflict reasserted itself after TARP. When the lame-duck House passed a bailout bill for the automobile industry on December 10, 2008, the vote was more normally liberal-conservative, with only fifty-four prediction errors. The vote was largely along party lines. Salvatore Nunnari has shown that the location and ownership of automobile manufacturing plants was important to this vote.65 Nonetheless, ideology is the primary determinant of roll call voting behavior. The Senate cloture vote failed by a 52–35 margin, with only eleven prediction errors. With a lame-duck president, Congress could not develop a coalition capable of supporting the auto industry. Gridlock forced a Republican president to turn against the foxhole ideologues in his own party and prop up Detroit on a short-run basis with TARP funds. The reappearance of a liberal-conservative split in the 110th Congress foreshadowed the legislative history of the 111th Congress.

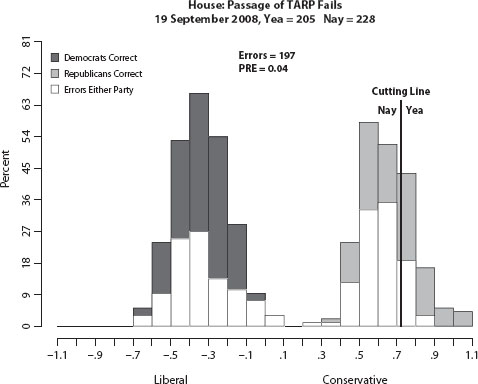

Between AHRFPA in July 2008 and the auto bailout votes in December, the standard liberal-conservative division fell apart over TARP. After Lehman failed on September 15 and AIG was bailed out a day later, Congress had to be dragged, kicking and screaming, with both liberal and conservative ideologues objecting, into approving the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA), which included the Troubled Asset Relief Program fund.

President Bush was largely absent. Liberals were reluctant to bail out the too-big-to-fail firms on Wall Street. Conservatives, even in a financial crisis, were reluctant to support government intervention in the economy. (The word nationalization became taboo in describing both the takeovers of Fannie and Freddie and the considerable government investment in AIG, Citigroup, General Motors, and other firms.) Populist outrage made legislators reluctant to support EESA, with the $700 billion TARP fund. Moreover, congressional elections were only weeks away. Indeed, the initial September 29 vote on TARP failed. On that day, the Dow lost nearly 800 points.

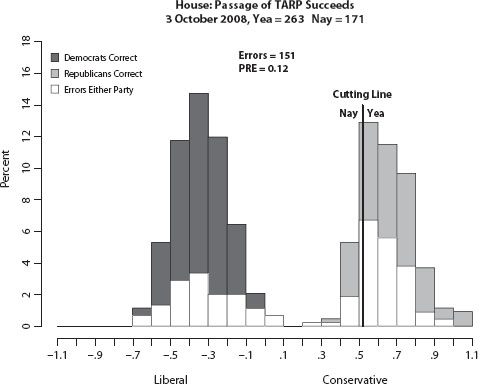

The votes on TARP were only weakly related to the liberal-conservative scale. The House votes, shown in figure 7.7, indicate that a liberal-conservative cutting line model fails to discriminate between supporters and opponents. There are 197 prediction errors on the failed September 29 vote and 151 on the October 3 passage vote, in contrast to only 9 on the stimulus plan, 21 on Dodd-Frank, and 47 on AHRFPA. In the Senate, there were 23 errors on passage on October 1, as against 1 on the stimulus, 4 on Dodd-Frank, and 6 on the Durbin amendment to AHRFPA.

The breakdown of the typical liberal-conservative alignment is nicely illustrated in the graph shown as figure 7.8. The graph plots the probability of House members voting for the bailout (TARP) as a function of the DW-NOMINATE score. There are three curves: one for safe seats, another for vulnerable seats, and another for seats where the representative had previously announced retirement. Those with vulnerable seats tended to cave in to populism and were the most likely to oppose the bill. Those with safe seats and especially those retiring were more likely to support the bill.

Why weren’t the Republicans running for reelection especially likely to vote for TARP? Would they have not wanted the party to escape the blame for an economic meltdown on the scale of the Great Depression? The answer is that when TARP was voted on, elections were only thirty-two days away. It might have been difficult to see either the benefits of approving or the costs of disapproving TARP within that time span. After all, even after TARP was enacted, the stock market continued to decline and unemployment rise for months. So it was easy, given the time frame, to cater to populist rage.

Very conservative Republicans voted consistently with their free market conservative ideology. They would have been more comfortable had Andrew Mellon’s ghost been Treasury secretary rather than Henry Paulson. Very liberal Democrats also were more likely to be against than for. Their egalitarian, redistributive ideology made them loath to bail out Wall Street firms, whose executives were royally compensated. There turned out to be more than a few ideologues in financial crises. The bill was supported mainly by moderates in safe seats, and even these members were not solid in their support. More detailed analyses that we and Mian, Sufi, and Trebbi have conducted indicate a small influence for other factors, such as receiving campaign contributions from the financial services industry.66

Figure 7.7. The two House votes on TARP. Neither vote is a good fit to a liberal-conservative model. There are almost as many prediction errors as votes on the minority side of each vote.

The rejection and subsequent passage of TARP reflected, in summary, several forces. The most conservative Republican members played ideologues, even in a financial crisis. So did the most liberal Democrats. The Right was unwilling to go against its beliefs that government intervention in the economy was bad per se, particularly so if it confirmed moral hazard. The Left was unwilling to support an upward redistribution to financial firms and their executives. Past campaign contributions of the financial sector were associated with just a slight marginal willingness to favor the bailout.67 Thus, ideological extremism trumped the supposed “capture” of Washington by Wall Street. On the other hand, members were more likely to help Paulson and Bernanke avoid a meltdown if they were not facing a reelection challenge in November.

Figure 7.8. The first House vote on TARP. Incumbents running for reelection in vulnerable seats were very unlikely to vote for TARP. Incumbents in safe seats were somewhat more likely to vote for it. Retiring incumbents were by far the most likely supporters. Moderates showed greater support than either extreme liberals or extreme conservatives. Note that the curves for retiring and vulnerable incumbents do not extend to the extremist ends of the graph (–1 and +1). This is because extremists are found only in safe seats.

One might have been wary that the TARP vote indicated political instability, such as that which preceded the Civil War after the Compromise of 1850 unraveled. Alternatively, there may have been a permanent political realignment similar to the replacement of the Whig-Democrat system with the Republican-Democrat system around the time of the Civil War.68 The Civil War events, as Nobel Prize Laureate Robert Fogel has stressed, were not ones of economics but ones in which, in the North, a moral aversion to slavery emerged.69 Financial panics are different. Not even the Great Depression led to realignment in congressional ideology. So it is not surprising that congressional Democrats and the Obama administration would be forced to form coalitions along the liberal-conservative dimension.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have argued that ideology largely reduces to one dimension. This ideology, with the exception of the turmoil in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers, proved very stable. On particular issues, specific economic interests can run counter to ideology. The influence of interest groups on roll call voting, however, does not generate a systematic second dimension. Mortgage foreclosures were significant to votes on AHRFPA but not on TARP or on the auto industry bailout. Similarly, financial services contributions affected only the TARP vote. Domestic auto manufacturer employment mattered only on the auto bailout. Currently, there is not an important, systematic second dimension in American politics beyond the liberal-conservative continuum. Highly polarized liberal-conservative politics and the power of pivots in American institutions made up the framework that generated the response to the pop of 2008. The configuration within which the president and Congress operate is determined by the influence of campaign contributions, lobbying, and elections.

In the short run, the behavior of financial markets can break the configuration. Intervention in the rotten market of subprime mortgages, bogus collateralizations, overleveraged banks, and incorrectly priced credit default swaps was long delayed because of ideological rigidity and interest-group pressures. After Bear Stearns, bailouts were taboo. Once Lehman went over the cliff, however, AIG was bailed out the very next day. TARP was quickly brought to Congress. Initially, ideology and electoral pressures led the House of Representatives to reject the proposal. The stock market then plunged off another cliff. Days later, Congress acquiesced. Once the worst was avoided, Washington returned to business as usual. Pivots ruled within established liberal-conservative ideology.