The Ethics of Labor Immigration Policy

Up to this point, the book has focused on exploring the characteristics and drivers of policies for regulating the admission and rights of migrant workers in high- and middle-income countries. The analysis has shown that labor immigration programs that target higher-skilled migrant workers are more open and grant migrants more rights than programs targeting lower-skilled migrant workers. It has also suggested that high-income countries’ labor immigration policies are often characterized by a trade-off between openness and specific rights granted to migrant workers after admission. The rights that have been restricted in practice as part of this policy trade-off include selected social rights, the right to free choice of employment, family reunion, the right to permanent residence (and thus citizenship), and—in countries that are not liberal democracies—selected civil and political rights. I have demonstrated how these policies may be explained by the national interests and policy constraints of immigration countries, and how they can be supported and sustained by the interests as well as choices of sending countries and migrants themselves.

This chapter moves the discussion from a positive analysis of what is to the equally important normative question of what should be. Given what we know about labor immigration policies in practice, what can we say about how high-income countries should regulate the admission and rights of migrant workers? Are TMPs that restrict migrant rights inherently unethical? If high-income countries’ labor immigration policies involve a trade-off between openness and some rights, as indicated in this book, what rights restrictions—if any—are acceptable in order to enable more workers to access labor markets in high-income countries? Is there a case for advocating new and/or expanded TMPs for lower-skilled migrant workers, whose access to labor markets is currently more restricted in high-income countries?

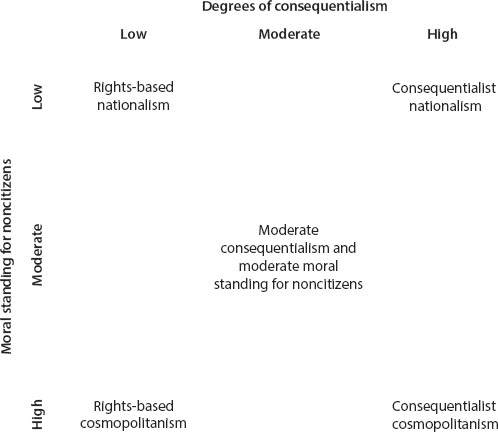

The chapter looks at these questions in four parts. The first examines the key ethical questions that arise in the design of any labor immigration program (again defined as involving policy decisions on how to regulate openness to along with the selection and rights of migrant workers).1 The discussion proposes a two-dimensional matrix of “ethical space” that isolates a number of different ethical frameworks based on the degree of “consequentialism” they allow and the “moral standing” they accord to noncitizens (migrants and people in migrants’ countries of origin). Different ethical frameworks have different implications for how to evaluate policies for regulating the admission and rights of migrant workers. As my intention is to contribute to national and international policy debates, I will argue for a pragmatic approach that is both realistic—by taking account of existing realities in labor immigration policymaking—and idealistic—by giving more weight to the interests of migrants and their countries of origin than most high-income countries currently do when designing labor immigration policies. Based on this combination of realistic and idealistic approaches, I explain and defend the five principles—or building blocks—informing my own normative approach to evaluating labor immigration policy.

The second part of the chapter draws on my normative approach in order to critically assess the main normative arguments against and for TMPs that restrict migrant rights. My discussion of the “case against” centers on three critiques based on human rights, equal membership, and exploitation. While each of these critiques is important within the context of their own normative starting points, I do not find them convincing given my own approach. As many of the existing normative defenses of TMPs suggest, in the context of an analysis that aims to contribute to real-world policy debates where some first-best policies are unfeasible, appropriately designed TMPs can be defended as “second-best” policies, notwithstanding their restrictions on migrant rights.

Having accepted the possibility of an ethically defensible TMP, the third part of the chapter examines which specific rights restrictions can be defended, and for how long. I argue for the unconditional protection of civil and political rights (except for the right to vote), and concentrate on other rights that are in practice most commonly restricted, and that have been part of a policy trade-off between openness and rights in high-income countries: social rights, the right to free choice of employment, the right to permanent residence, and the right to family reunion. I contend that given certain conditions and supporting policies, some restrictions of these rights are justifiable in exchange for better access to high-income countries’ labor markets. Key supporting policies include measures that protect migrant workers’ agency, such as their ability to make informed choices, and act on their decisions to both join and exit a particular labor immigration program.

The fourth and final part of the chapter discusses whether and how temporary labor immigration programs, especially for low- and medium-skilled migrant workers, can be in the national interest of migrant-receiving countries—a crucial issue set aside in the discussion of normative issues in the first three parts of the chapter. I focus on two sets of policy measures that are necessary to make low-skilled temporary labor immigration benefit receiving countries: the need to manage employer demand for migrant labor, and measures that facilitate the return of migrant workers whose temporary work permits have expired.

The aim of this chapter is to engage existing ethical theories in order to develop a normative framework and advance an argument for how to evaluate labor immigration policy, including the policy trade-offs between openness and rights that have been identified in this book’s empirical analysis. It is essential to emphasize at the outset that there is no one right answer in this normative debate; indeed, there are few obvious or clear answers to any of the questions analyzed in this chapter. The analysis below thus inevitably reflects my own personal and ongoing struggle with what are exceedingly difficult dilemmas. I do develop my own normative position and policy implications at the end of the chapter, but I hope that readers who disagree with my particular approach will still be able to engage with the bulk of the chapter in a meaningful way.

What Consequences Should National Policymakers Care about, and for Whom?

International labor migration generates a complex set of economic, social, political, cultural, and other consequences for individuals, communities, and countries as a whole. Table 7.1 categorizes the major types of impact (each indicated by an x) on nonmigrants in the migrant-receiving country, nonmigrants in the migrant-sending country, and migrants themselves. The categories and distinctions in the table are clearly crude and in many ways unsatisfactory, but the table is useful as a device for a basic conceptualization and discussion of different types of impacts on different groups.

The types of impact included in the table reflect the major objectives of policymaking mentioned in earlier chapters of the book: economic efficiency/welfare; distribution; national identity/social cohesion; national security and public order; and individuals’ rights.2 The distinction between migrants and nonmigrants in sending and receiving countries is meant as a conceptual simplification that does not address the important, interrelated questions of how to define migrants (e.g., all foreign-born persons or only foreign nationals?), and whether and how to distinguish between different groups of migrants (e.g., short- and long-term migrants). For clarity and simplicity—and not for normative reasons—the discussion below will assume that the groups of nonmigrants in receiving countries are restricted to citizens of the receiving country. The term noncitizen in the exploration below thus refers to migrants and their countries of origin.3

The design of national labor immigration policy requires national policymakers to define the policy objectives (the “social objective function”), in a process that can be conceptualized as assigning weights to the different types of impacts listed in table 7.1. What impacts and whose interests should labor immigration policy serve?4

TABLE 7.1. Types of impacts of international labor migration

Notes: RC = migrant-receiving country; SC = migrant-sending country; M = migrants.

To identify and disentangle the key ethical issues in this inherently normative exercise, it is useful to distinguish between two main questions: To what extent, if at all, should the outcomes for collectives (such as economic efficiency or distribution) and the economic welfare of individuals be given priority over individuals’ rights? And to what extent, if at all, should the interests of citizens of receiving countries be given priority over those of noncitizens (migrants and people in the migrants’ countries of origin)? In order to scrutinize the ethical bases for making these decisions, it is necessary to address the more general (and much-debated) questions of what degree of consequentialism should be employed in the evaluation of alternative policy designs and what moral standing national policymaking should accord to noncitizens.

What Degree of Consequentialism?

An action (including policy) may be described by its consequences (or outcomes) and the means (or processes) by which the consequences are generated. Accordingly, the ethical evaluation of an action may concern itself with either consequences or processes, or with both. Different ethical theories disagree on the extent to which assessments of consequences and processes should enter into the overall ethical evaluation of an action. The degree to which the ethical evaluation is made in terms of outcomes (ends) rather than processes (means) may be used to locate moral theories along a spectrum bound by a minimally consequentialist position at the lower end and a strictly consequentialist position at the upper end.5

The theory that probably comes the closest to being “minimally consequentialist” is Robert Nozick’s (1974) version of libertarianism. In Nozick’s world, rights are simply “side constraints” on the actions of individuals who may otherwise do as they wish.6 The policy imperative for the “minimal state” that Nozick (ibid., 26) advocates thus is to protect individuals’ rights by protecting all its citizens against violence, theft, and fraud, and ensure the enforcement of contracts. It follows that policies are to be evaluated only in terms of their consequences for individuals’ rights, with little or no regard for their consequences for individuals’ well-being or collective interest as a community.7 The main difficulty with this approach is that there is no universal hierarchy among conflicting rights, such that the policymaker needs to decide which rights should be given priority.8

At the other end of the spectrum, strict consequentialism is defined as the extreme proposition that an action is to be evaluated in terms of its consequences alone, and therefore that an action is permissible if there is no alternative with “better” consequences, however measured.9 Classical utilitarianism is an example of a strictly consequentialist position, in which the objective of a just society is to achieve the greatest net balance of satisfaction summed over all its members.10 It is implied that the consequences justify the means of private action and public policy. Importantly, consequentialism is silent on the crucial question of how to weigh consequences for different groups within society.

To be sure, if all ethical theories were to be situated along a one-dimensional spectrum of consequentialism, most of them would be found somewhere in between the two extremes. It may be plausibly argued, for instance, that of the two Rawlsian principles of justice, the “priority of liberty principle” is a nonconsequentialist principle, while the “difference principle” is consequentialist in nature (as it makes the consequence for the distribution of welfare an ethically permissible standard for policy evaluation).11 Similarly, by considering freedom as the end and primary means of development, Sen (1999, 86) advocates a partly consequentialist theory that “can take note of, inter alia, utilitarianism’s interest in human well-being, libertarianism’s involvement with processes of choice and the freedom to act and Rawlsian theory’s focus on individual liberty and on the resources needed for substantive freedoms.”

The desirable degree of consequentialism in the ethical evaluation of public policies (or moral judgment of private action) has been a much-debated problem in moral philosophy.12 It is not my intention to take a specific position in this debate, or discuss critically some of the arguments in favor of or against any particular degree of consequentialism. I merely want to point out that the design of labor immigration policy, or more generally any argument on labor immigration, is necessarily based—either explicitly or, as has been the case more often, implicitly—on an underlying ethical framework that is characterized by a specific degree of consequentialism, as derived from a particular stance in the rights versus consequences debate.

What Moral Standing for Migrants and Their Countries of Origin?

Having decided on the degree to which consequences should inform the design of a labor immigration program, the policymaker needs to determine for whom consequences should be taken into account. In other words, should national policymaking only consider the consequences of immigration for citizens in the receiving country, or should it also consider the consequences for noncitizens (migrants and people in migrants’ countries of origin)? Furthermore, if the policymaker factors in the consequences for noncitizens, should the consequences for all citizens and noncitizens be given equal weights? If not, what should determine the degree to which the policymaker lets the consequences for migrants and their countries of origin influence the design of the labor immigration program?

The answers to these questions depend on the degree of moral standing that the national policymaker accords to noncitizens. Most discussions of immigration policy and indeed most contributions to moral philosophy tacitly assume that the national policymaker accords full moral standing to citizens only. Conversations about the moral standing of noncitizens are scarce and frequently avoided. I maintain, however, that a comprehensive assessment of how consequences should affect labor immigration policy must include an explicit look at the moral standing of noncitizens.

As a first step in that direction, it is necessary to acknowledge that as with degrees of consequentialism in moral theories, there is a spectrum of degrees of moral standing that the national policymaker may extend to noncitizens. This spectrum is bound by minimal moral standing, on the one end, and maximal (almost-full) moral standing, on the other. I exclude the cases of no (or zero) and full moral standing for noncitizens as unrealistic and untenable positions. The former would imply that the country does not treat noncitizens as human beings, while the second makes the concept of citizenship meaningless.

Advocates of a minimal moral standing for noncitizens usually employ what Simon Caney (1998, 32) calls the “negative arguments from anarchy.” This approach comes in three versions, suggesting that due to the absence of an international community that defines as well as enforces rights and duties; the lack of significant cooperation among nation-states; or the lack of international cooperation motivated by cosmopolitan ideals, nation-states are under no obligation to include ethical considerations in their dealings with foreigners. A more positive claim for according a low moral standing to noncitizens proposes that it is a moral duty for a nation to follow the national interest (narrowly understood as the promotion of the interests of citizens only) in its dealings with other nations.13

In contrast, many of those who believe in maximal (almost-full) moral standing for noncitizens hold that there is a set of (comprehensive) universal rights to which everybody is entitled, regardless of their citizenship status. One of the most prominent examples of a position that comes close to this “ethical cosmopolitanism” is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As discussed in chapter 2, while still allowing nation-states to regulate who and how many migrants to admit, the CMW and other human rights treaties emphasize that human rights are universal (that is, they apply everywhere), indivisible (political and civil rights cannot be separated from social and cultural rights), and inalienable (they cannot be denied to any human being, and should not be transferable or salable).

Advocates of ethical standpoints that lie between the described extremes of nationalism and cosmopolitanism contend that just because certain moral principles are not completely enforceable at the international level, or are not embraced by other countries, a state cannot deny all ethical duties toward noncitizens. They argue that a strict ethical cosmopolitanism (for example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) is equally problematic because it clashes with anticosmopolitan institutions such as states in the real world.14 In other words, where nation-states are the guarantors of cosmopolitan rights, there is a natural tendency toward friction and conflict between the rights of citizens and noncitizens. For these and many other reasons, few people subscribe to any of the two extreme views (just as few people advocate a strictly or minimally consequentialist position), but support a position of what may be called moderate cosmopolitanism, which incorporates elements of both nationalism and cosmopolitanism. For example, Charles Beitz (1983) suggests that a moderately strong cosmopolitan view would include the duty to pursue cosmopolitan goals with an upper boundary on the associated cost, with the upper boundary defining the degree of priority that a government accords to its citizens’ interests.

Just as it is difficult to identify and ethically justify the appropriate degree of consequentialism, it is no easy task to justify a specific degree of moral standing for noncitizens.15 Again, I do not want to argue in favor of a particular moral standing but rather point out that the way in which consequentialism should influence the design of a labor immigration program critically depends on what degree of moral standing the policymaker extends to noncitizens.

It is useful to conclude this section by summarizing the main arguments with the help of figure 7.1.16 The figure makes it clear that the role of consequences in the design of labor immigration policy depends on the degrees of consequentialism and the moral standing extended to noncitizens. Together, they constitute an ethical framework for the evaluation of labor immigration policy.

Different ethical frameworks have different implications for the objectives and design of desirable labor immigration policy. By way of illustration, it is useful to briefly think through some of the basic implications of the four frameworks that make up the corners of the ethical space in figure 7.1. Under consequentialist nationalism—the framework that, arguably, comes closest to the reality we currently observe in most countries–openness, selection, and rights are determined based on an assessment of the consequences for economic efficiency, distribution, national identity, and security in the receiving countries—with little to no importance given to the outcomes or rights of migrants and people in their countries of origin. For instance, points-based systems that aim to “optimally select” migrants in terms of their skills and other characteristics in order to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of immigration for the receiving country can be justified by a normative framework of consequentialist nationalism. Guest worker programs that restrict the employment of migrants to specific sectors of the labor market that suffer from labor shortages and that limit migrants’ access to the welfare state are another example. This normative approach is typically associated with two major challenges. First, it inevitably leads to controversies and debates about the methods as well as conclusions of impact assessments. Second, consequentialist nationalism is silent on the question of which of the four objectives—economic efficiency, distribution, national identity, and security—should be given the most weight and how trade-offs should be evaluated.

FIGURE 7.1. Examples of ethical frameworks (ethical space)

Consequentialist cosmopolitanism requires labor immigration policies to be informed by the outcomes (rather than the rights of) all people, such as migrants as well as nonmigrants in receiving and sending countries. As migration can create large benefits for migrants and their countries of origin, the number of admitted foreign workers under a cosmopolitan position is likely to be higher than that under a position with a low degree of moral standing for noncitizens. In fact, it could be claimed that if economic efficiency and distribution were the only outcome parameters, consequentialist cosmopolitanism would require open borders, as the free flow of labor increases world welfare and decreases global inequality.17 Importantly, consequentialist cosmopolitanism would tolerate a restriction of migrant rights as long as the consequences of more migration create net benefits for migrants’ welfare or other measures of well-being. Consequentialist cosmopolitanism thus can and has been used to justify and advocate new, expanded guest worker programs that combine better access to global labor markets with restrictions of rights—especially for lower-skilled migrants.18

Under rights-based cosmopolitanism, the policy imperative is to protect to an equal degree the individual rights of all people, that is, migrants as well as nonmigrants. It can be argued that the policy principles of the CMW—universality, inalienability, and indivisibility—are based on an ethical framework for rights-based cosmopolitanism. While this normative framework does not provide ready-made answers to the question of what to do if there are competing rights between different groups, it is clear on the implications for labor immigration policy and guest worker programs: policies that involve restrictions of rights are morally unacceptable even if they create “good consequences” for other outcomes, such as countries’ economies or individual’s economic welfare.

Finally, rights-based nationalism requires that immigration policy be driven by a concern for protecting the rights of citizens in the receiving country. As is the case with rights-based cosmopolitanism, a key question within this approach is how to evaluate the rights of different groups like employers and workers. If employers’ rights to contract are given priority, immigration policy would need to be much more open to admitting migrants than would be the case if workers’ rights were prioritized.

While not everybody might agree with the particular way in which I have drawn implications for labor immigration policy from each of these four ethical frameworks, I hope that the brief discussion has at least shown how different normative starting points can lead to sometimes radically different policy implications.

Struggling for a Normative Framework: Building Blocks of My Approach

Given the multitude of competing ethical theories and frameworks, how should we choose and justify one over the others? There is no single most correct starting point for theoretical reflection in the ethical discourse on immigration.19 As normative discussions are critically informed by values rather than just “facts,” people with different values may reasonably disagree about the most desirable degrees of cosmopolitanism and consequentialism in the evaluation of public policies. Any considered argument for a particular normative approach necessarily reflects the current outcome of an ongoing struggle with what are exceedingly difficult normative issues as opposed to firm conclusions of a “scientific” exercise. The perhaps obvious but often overlooked implication is that any case for a particular normative starting point needs to be clearly justified and argued, and made with some humility.

With these caveats, the discussion below develops five core considerations (or building blocks) of my own normative approach to labor immigration policy, including questions about how to respond to trade-offs between openness and rights.

My argument begins with the distinction between what Joseph Carens (1996) calls the “realistic” and “idealistic” approaches to morality. The realistic approach is firmly based on existing realities, and stresses the importance of avoiding overly large discrepancies between the ought and the can. In contrast, the idealistic approach is less constrained by considerations of practicality and focuses only on what ought to be, regardless of whether or not the implied policies are currently feasible. Carens (ibid., 169) makes the important point that “the assumptions we adopt should depend in part on the purposes of our inquiry.” If the objective of the ethical discourse is to yield practical policy implications—as it is in this chapter—there is a strong argument to be made for adopting a combination of both approaches. On the one hand, idealistic considerations are needed to “break new ground” in thinking about ethics and public policies. On the other hand, if the discussion is to yield any practical policy implications, there must be a significant realistic component. Timothy King (1983, 533) makes the eminently sensible point along this line that “to ask people to accept policies which threaten to lower their own well-being sharply in the name of some abstract moral principle is clearly impracticable.”

My own interpretation of what it means to combine a realistic and idealistic approach to the ethics of labor immigration policy leads me to advocate an “enlightened national interest” approach, which is based on the following two considerations:

1. Acceptance of the need for national labor immigration policy to prioritize the interests of citizens. In a world of sovereign nation-states, national policymakers must prioritize—at least to some extent—the interests of citizens over those of migrants and their countries of origin. This means that whenever there are trade-offs between impacts on citizens and noncitizens, policy can legitimately prioritize the former over the latter.

2. Recognition of the duty to actively promote the interests of migrants and their countries of origin. International labor migration has significant impacts, and can generate considerable benefits for migrants and their countries of origin. Yet most national labor immigration policymaking is based on near-exclusive concerns with the interests of citizens of receiving countries. Given global poverty and inequality, there is an ethical mandate to look for ways in which opportunities for international migration—especially for low-skilled workers in lower-income countries—to access labor markets in high-income countries can be expanded.

The first of these considerations reflects the need to be realistic about current policymaking and what can be expected of national policymakers. The second consideration is based on my personal concern, undoubtedly shaped by my own experiences as a migrant in different countries and cultures, with the cosmopolitan goals of reducing global poverty and inequalities while promoting global justice. I am attracted to arguments for a national interest approach that include—as, for example, Beitz (1983) has suggested—a duty to pursue cosmopolitan goals, but with a constraint that is based on a limit to the costs imposed on citizens.

With regard to rights, my normative approach combines a fundamental recognition and respect for some of the basic principles of human rights with the avoidance of “rights fetishism,” and an active consideration of the agency of and choices currently made by migrants and their countries of origin:20

3. Recognition of the moral weight of human rights principles. The principles enshrined in international human rights treaties, such as dignity and equality, carry important moral weight and have become widely accepted reference points in public debates in liberal democracies. Any restriction of migrant rights along with the derogation of the principle of equality is, in some fundamental sense, morally problematic and needs to be justified by strong arguments.

4. Rejection of rights fetishism. As rights are not the only dimension of human development (or human well-being), they should not be used as the sole criterion for evaluating the moral desirability of immigration policies. The agency, choices, and interests of migrants and their countries of origin need to be considered when evaluating immigration policies that involve restrictions of migrant rights.

In terms of figure 7.1, I am making the case for a normative approach that is located in the “ethical subspace” of moderate degrees of both cosmopolitanism and consequentialism, where moderate does not imply a perfect balance but instead simply the exclusion of extreme ethical framework along the borders of figure 7.1. Cynics might maintain that this constitutes a cheap “centrist cop-out.”21 It does not. For the reasons given above, I strongly believe that to have any chance of success in the real world, an approach that aims to pursue cosmopolitan policy goals needs to balance the legitimate self-interest of nation-states with the interests of migrants and their countries of origin. At the same time, any approach that purports to consider the overall interest and human development of migrants needs to reject rights fetishism while taking seriously any restriction of migrants’ rights. My approach implies that there are no easy choices in labor immigration policy. All morally desirable labor immigration policies, I contend, must involve at least some balancing of rights and consequences as well as the interests of citizens and noncitizens.

This brings me to the fifth and final core consideration of my normative approach:

5. No presumption in favor of a one-size-fits-all approach. The ethics of labor immigration policy of sovereign nation-states may, at least to some extent, be specific to country and time.

This consideration is based on the recognition that there are significant contextual differences between different countries. These differences are manifested, for example, in differences of economic development, cultural and social values, international relations with specific migrant-sending countries and the world community as a whole, the role and power of the judiciary, and perhaps most important in the context of a normative debate, the actual capacity of the state to act and implement certain policies (compare this to the discussion in chapter 3 about variations in institutions and constraints of immigration policymaking across different countries).22 Given the sovereignty and self-determination of nation-states, these contextual differences suggest that there is unlikely to be a single ethical framework and corresponding labor immigration policy that can be identified as the most desirable one for all countries at all times. Rather than looking for a one-size-fits-all ethical framework and labor immigration policy, we need to allow for ethical valuations that may, at least to some extent, vary across countries and over time. This does not equate to an argument for ethical relativism, implying that morality is relative to prevailing social norms and culture. It does suggest, however, that while we may identify some universal principles and features of an ethical labor immigration policy, there may be some morally defensible variations of specific policy aspects.

The five building blocks discussed above indicate the broad features of my normative approach. While outlining some important starting points, as a whole they still leave room for a wide range of different evaluations and associated policy implications. In the next section, I use these five considerations as a basis for critically examining some of the main normative arguments in favor of and against restricting migrant rights under TMPs.

The Ethics of Temporary Labor Immigration Programs

All temporary labor migration programs restrict at least some of the rights of migrant workers. The empirical analysis in chapters 4 and 5 has shown that labor immigration programs that target lower-skilled migrants restrict more rights than those targeting higher-skilled migrants. It has also found evidence of a trade-off between openness and some rights: programs that are more open to admitting migrant workers are often more restrictive in terms of the rights they accord to migrant workers. As shown in chapter 6, migrants and sending countries are acutely aware of and actively engage with these trade-offs, frequently tolerating rights restrictions in exchange for better access to the labor markets of higher-income countries.

Are temporary labor migration programs that restrict the rights of migrant workers fundamentally objectionable from a moral point of view?

Three Critiques: Human Rights, Equal Membership, and Exploitation

One of the most common normative critiques of TMPs, especially of programs for admitting low-skilled migrant workers, is based on the argument that they violate fundamental principles of human rights. There is debate about the exact interpretation of the rights and protections stipulated in international legal instruments. Not all human rights are absolute, and it is clear that these instruments do allow for some distinction between the rights and entitlements of citizens and noncitizens.23 It is equally clear, however, that many (although not necessarily all) of the temporary labor migration programs and associated rights restrictions in high-income countries are not compatible with the human rights principles of universality, indivisibility, and inalienability, and the specific rights stipulated in the CMW in particular. Universalistic rights-based theories oppose the active promotion of new policies that are based on an explicit distinction between the rights and entitlements of different categories of residents (such as temporary residents, permanent residents, and citizens).

A quite different but equally powerful critique of TMPs is based on the assertion that a democratic national community must provide all its members with equal “terms of membership” and access to citizenship rights. This argument has been made, for example, by Michael Walzer, a communitarian who suggests that the political community can be thought of as a “club” or “family.” He contends that if migrant workers are admitted into the political community, they must be given equal rights and opportunities to be set on the road to citizenship. Any other arrangements would constitute a “family with live-in servants.” Walzer (1983, 61) summarizes the issue of guest workers as follows:

Democratic citizens, then, have a choice: if they want to bring in new workers, they must be prepared to enlarge their own membership; if they are unwilling to accept new members, they must find ways within the limits of the domestic labor market to get socially necessary work done. And those are their only choices. Their right to choose derives from the existence in this particular territory of a community of citizens; and it is not compatible with the destruction of the community or its transformation into yet another local tyranny.

A strong defender of the national community’s right to limit immigration, Walzer makes it clear that not admitting migrant workers at all is better than admitting migrants under restricted rights—not because it is better for migrant workers, but because it is better for the national community. David Miller (2008, 376) makes a similar argument, acknowledging that the requirement of equality of citizenship rights will often result in the admission of fewer migrant workers:

These are the reasons, I believe, why admitting immigrants poses greater problems for contemporary states than it did for liberal states a century ago: they have to be admitted as equal citizens, and they have to be admitted on the basis that they will be integrated into the cultural nation. These are both potential obstacles to admission, insofar as they impose costs and constraints on the receiving state.

A third argument against TMPs is that they are inevitably exploitative—a slippery concept, as I explain below. While this claim frequently builds on egalitarianism (universal as in human rights, or within the national community as in Walzer’s case), it has also been made based on neoclassical theories of economics. Daniel Attas (2000), for example, maintains that the source of exploitation in guest worker programs is not political—the source is not the denial of political rights and access to citizenship (as Walzer argues) but rather the denial of equal economic rights. Attas holds that because of the restriction of specific labor rights—especially the right to free choice of employment—guest workers receive a wage that is lower than their marginal product of labor in equilibrium (i.e., lower than the wage they could obtain if they were free to take up employment that pays the highest wage for their labor in the economy). This constitutes an “unequal exchange” (i.e., an exchange where one party does not receive their fair or just share), which under most definitions is a key characteristic of exploitation. Attas (ibid., 88) puts forth that the removal of the restriction of economic rights could eliminate exploitation in guest worker programs.

Thus, although there may not be sufficient grounds to require the admission of guest workers to full political citizenship, full economic membership seems justified. This might be all that is needed to expel the spectre of exploitation. Were guest workers to enjoy the same economic rights as local workers, and particularly the freedom of occupational choice, then the cause of unequal exchange would be removed.

These three arguments constitute important, powerful critiques of TMPs based on specific normative starting points. Within my own normative framework, though, I do not find any of these fundamental critiques convincing. I have three interrelated concerns about the three assertions: the critiques are concerned with a set of interests that I consider too narrow; they give insufficient weight to alternatives, such as to the consequences of rejecting guest worker programs for migrants and sending countries; and they do not place sufficient emphasis on the agency, interests, and actions/policies of migrants and their countries of origin.

As I will argue in more detail in the concluding chapter, human rights critiques often (but not always) fail to consider the potential consequences, such as greater economic welfare and human development, that TMPs may generate for migrants and others. While I am not claiming that consequences should always trump rights, I find it hard to see how a strictly rights-based argument that does not give any weight to the impacts of migration for the welfare or well-being of rights holders can be in the best interest of migrants, especially if migrants are currently making choices that suggest that they value rights and improvements in economic welfare along with other dimensions of human development (see the discussion in chapter 6).

Communitarian rationales such as Walzer’s are primarily (and in some cases only) concerned with the collective interests of the national community in the receiving country, with little to no consideration for the interests of individual potential migrants (still in the sending country and seeking employment abroad), or those of the sending country in general. Within my normative approach, the argument that temporary labor migration programs are objectionable because they change the nature of the community in the receiving country and therefore are, in some sense, “bad for us” is not sufficient for opposing such programs. A realistic approach has to accept, of course, that immigration countries may not want immigration to radically change the nature of their community, but this does not exclude a consideration of policies that involve relatively small adjustments (e.g., the acceptance of a temporary presence of migrant workers who enjoy most yet not all the rights of citizens) in exchange for large benefits for migrants and their countries of origin.

My objection to the exploitation proposition is not that I disagree with the assessment that TMPs are exploitative based on the most commonly used definitions of exploitation. Rather, my concern is that such arguments often do not give a convincing account of why guest worker programs that exploit are ethically inferior to what would happen under realistic alternative policy scenarios. I consider and develop this notion more fully after reviewing some of the main points in defense of TMPs.

No Escaping from “Second Best” and “Dirty Hands”: The Normative Defense of TMPs

Most normative defenses of TMPs begin with the observation that such policies inevitably constitute second-best policies that lead to dirty-hands solutions. Howard Chang, for example, defends and advocates for the use of guest worker programs for low-skilled workers as second-best policies. Chang suggests that from the perspective of liberal principles of global social justice, first-best migration policies would involve more open borders as well as legal permanent residence with access to all citizenship rights. He considers this first-best policy as politically unfeasible as it would create fiscal burdens that residents of the receiving country would be unwilling to accept. Given this political feasibility constraint, Chang proposes TMPs that selectively restrict migrants’ access to the welfare state while at the same time “seeking the broadest rights possible for aliens within the constraints of political feasibility.” Chang (2002, 15) draws attention to the need to consider the alternatives along with the agency and choices of migrant workers themselves: “If guest worker programs make us uneasy, then exclusion should only make us more so, because it keeps alien workers in a state of poverty that they would prefer to escape as guest workers.”

Daniel Bell (2006) makes a similar argument in the context of labor immigration policies in East Asia. His analysis of foreign domestic worker programs in Singapore and Hong Kong led him to conclude that there is no realistic prospect of foreign domestic workers obtaining equal access to citizenship rights. In other words, equal rights are politically infeasible. Bell (ibid., 297) states that “the fact that the door is closed to equal rights does have one practical benefit—it means that there are more doors open to temporary contract workers.” Comparing foreign domestic workers programs in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Canada, Bell notes that while the programs in Hong Kong and Singapore are much more restrictive in terms of rights than the Canadian program (Canada’s Live-in Caregiver Program grants migrants access to permanent residence after two years working in Canada), Singapore and Hong Kong admit many more foreign domestic workers relative to their population size than Canada. Bell (ibid., 297–98) thus observes: “The choice, in reality, is between few legal openings for migrant workers with the promise of equal citizenship and many openings for migrant workers without the promise of equal citizenship.”24

Emphasizing the importance of migrant agency and considering alternatives to guest worker programs, Bell (ibid., 304) proposes three conditions that may justify unequal rights for migrant workers: if “(1) this arrangement works to the benefit of migrant workers (as decided by migrant workers themselves); (2) it creates opportunities for people in relatively impoverished societies to improve their lives; and (3) there are no feasible alternatives to serve the ends of (1) and (2).” In an interesting twist, Bell suggests that these conditions can justify unequal rights for temporary migrant workers in East Asia, but not necessarily in Western liberal democracies that do not share the values and cultural peculiarities underpinning East Asian societies. Bell explicitly warns against the “exportability” of his analysis.

A third and related line in defense of TMPs addresses the critique that such programs are inevitably exploitative. In an important article on guest workers and exploitation, Robert Mayer (2005) contends that the fact that guest worker programs are exploitative (he argues that this is not always the case) does not necessarily imply that they should not be tolerated. Like Bell, Mayer defends TMPs, even when they are exploitative, under certain conditions. Mayer’s criteria are not too dissimilar from the conditions offered by Bell. In contrast to Bell, however, Mayer (ibid., 311) does not limit the applicability of his analysis to specific national or cultural contexts: “Even when guestworker programs are exploitative, it is argued that the unfairness should be tolerated if the exploitation is modest, not severe, and if the most likely nonexploitative alternative worsens the plight of the disadvantaged.”

The implementation of this approach in practice requires a definition and measure of exploitation in general and modest exploitation in particular. Different people disagree on how to define and measure exploitation. Mayer (ibid., 317) is critical of egalitarian and neoclassical theories of exploitation, as they are “too sweeping and indiscriminate in their judgements.” In developing his own theory and argument, Mayer starts with the example of highly skilled and highly paid migrants working abroad on temporary employment contracts. Mayer claims that such “privileged guests” do not seem to be exploited even when they work under restricted rights (e.g., no free choice of employment and no access to citizenship). He suggests that this instance points to the need for a more sensitive standard of exploitation. Mayer proposes a “sufficiency theory of exploitation,” suggesting that only people who are below a threshold of sufficiency can be exploited. In other words, guest workers who “have enough” in their home countries before considering migration (i.e., who start from a position of financial sufficiency) cannot be exploited. A job offer under a guest worker program is exploitative only if migrants who do not have “enough” in their home countries would be the only ones to accept the job offer. The assessment of whether exploitation is happening in practice then hinges on our assessment of what constitutes enough in any given case. Mayer asserts that the German Gastarbeiter program was less exploitative than the US Barcero program because the wages and conditions on offer under the German program (which were similar to those provided to German workers) would have encouraged workers who have enough in Turkey to participate in the program,, whereas the tough working conditions and low take-home pay (after deducting various migration costs) of Braceros would have been unacceptable to Mexicans who start from a position of sufficiency in Mexico.

All three arguments in favor of TMPs are very much grounded in a realistic approach to the ethics of migration that requires us to engage with second-best and dirty-hands policies as well as the agency and choices that migrants make. I very much share this approach. I disagree with arguments that reject TMPs—and the inherent trade-offs between openness and rights—outright without offering realistic alternative policy scenarios that will provide better outcomes than the guest worker option.

The key question is whether there are any “clean-hands” alternatives to TMPs that lead to better outcomes. I am skeptical, especially when it comes to the migration of low- and medium-skilled migrant workers. As shown in chapters 4 and 5, permanent labor immigration programs that grant close to equal rights are generally reserved for highly skilled migrants. My empirical analysis of labor immigration programs strongly suggests that expecting countries to both admit more low- and medium-skilled migrants and grant them equal rights is not a realistic scenario in the short to medium term. The most likely clean-hands alternative to guest worker programs for low- and medium-skilled workers is exclusion. Based on my analysis of the interests and choices of migrants along with their countries of origin (see chapter 6), I do not see any evidence to indicate that exclusion leads to better outcomes for migrants and sending countries than participation in a guest worker program.

My own normative approach thus leads me to reject the three fundamental critiques of TMPs provided by human rights, communitarianism, and arguments about exploitation. There is, in my view, a strong case for considering—as Chang, Bell, and Mayer each do in slightly different ways—the expansion of temporary labor migration programs that selectively restrict migrant rights, but at the same time provide many more workers access to the labor markets of higher-income countries.

What Rights Restrictions Are Justifiable, and for How Long?

If we accept the possibility of an ethically defensible temporary labor migration program, two other important normative questions arise: What specific rights of migrant workers should we allow to be restricted under such programs, and for how long?

Given my particular normative approach, my starting point for addressing this question is that no labor immigration policy should restrict migrants’ basic civil and political rights, with the crucial and widely accepted exception of the right to vote in national elections. Any normative approach that purports to be concerned about human rights, including my own, at a minimum must surely call for the protection of civil and political rights. So I advocate a “firewall” around civil and political rights in all policy debates on temporary labor migration programs.25 If restrictions of civil and political rights are part of a policy trade-off that facilitates greater openness to admitting migrant workers than would otherwise be the case—as is currently true in some countries in the Middle East and Southeast Asia—the significance of protecting basic civil and political rights is, in my view, worth the “cost” of reduced access for potential migrants to labor market in these countries.

With regard to other rights, rights restrictions under temporary labor migration should be limited to those rights that demonstrably can be shown to create net costs for the receiving country, and hence may be part of a policy trade-off between openness and rights that high-income countries are likely to make in practice. The specific rights this applies to will, to some extent, vary from one country to another (e.g., depending on the characteristics of the welfare state). The empirical analysis of labor immigration programs in chapters 4 and 5 of this book suggests that the trade-offs that we observe in practice in liberal, democratic high-income countries have involved a few specific rights, including selected social rights, the right to free choice of employment, the right to family reunion, and the right to access to permanent residence. Based on the discussion above, there is a strong normative case for limiting any potential rights restrictions to these rights and calling for the equality of all other citizenship rights (except, as mentioned above, the right to vote in national elections).

Social Rights

As discussed earlier in the book, the legal access that migrant workers have to the welfare state is a critical determinant of their net fiscal contribution—the difference between the taxes they pay and the public services and benefits they receive. In countries with progressive taxation systems and welfare states that redistribute from the rich to the poor, low-paid workers can be expected to make a smaller tax contribution and greater use of welfare benefits than higher-paid workers. The net-fiscal effects of low-skilled immigration are often negative. Consequently, the extent to which low-skilled labor immigration benefits the host country is partly dependent on the degree to which low-skilled migrant workers’ access to the welfare state can be restricted —hence the trade-off between openness and selected social rights in practice (see the discussion in chapters 3, 4, and 5).

Which social rights can justifiably be restricted under a temporary labor migration programs? My answer comes in two parts. The first repeats the general point made above: any restriction of social rights is only defensible if there is demonstrable evidence—not just a perception—that granting the rights would indeed create a net fiscal loss for the receiving country, and because of this, lead to reduced openness to admitting migrant workers.

Second, when thinking about the specific social rights that may be restricted under temporary labor migration programs, I agree with Carens’s basic distinction between social benefits that are based on prior employment and tax contributions (contributory benefits) and those that are based on low income, such as means-tested benefits aimed at helping the poor. The moral argument for restricting access to contributory benefits is much weaker than that for limiting access to means-tested benefits (such as social housing, low-income support, education grants for low-income earners, etc.). As Carens (2008, 430) argues, “Since the goal of the programs is to support needy members of the community and since the claim to full membership is something that is only gradually acquired, exclusion of recent arrivals does not seem unjust (although it may be ungenerous).”

The distinction between contributory and means-tested benefits also can be justified in terms of costs and benefits for the receiving country. The net costs of providing access to means-tested benefits to low-paid workers is likely to be significantly greater than that of providing access to contributory benefits. In most countries, nobody (regardless of citizenship) can receive contributory benefits unless they have been employed and paid taxes for a minimum period, so access to contributory benefits is always restricted in that fundamental sense.

Restrictions to access to health services are, in my view, hard to justify given that the denial of health care often will create more costs than benefits for the receiving country (e.g., if migrants with infectious diseases cannot attend medical services). As regards education, a case can be made for restricting temporary migrant workers’ access to public education, since the primary purpose of admitting migrant workers is employment and not study. I do not, however, support restrictions on the access to public education for the children of migrant workers (if they are admitted as discussed below).

The Right to Free Choice of Employment

As noted earlier in the book, restrictions of the right to free choice of employment are necessary to enable migrant-receiving countries to use temporary labor migration programs as a tool for responding to labor shortages in specific sectors and/or occupations of the labor market. Without this restriction, much of the receiving country’s rationale for establishing temporary labor migration programs in the first place is significantly reduced. It is important to emphasize that the necessary constraint on free choice of employment is one that restricts migrants to work in specific sectors and/or occupations, not with specific employers, as is currently the case under many programs. One of the primary sources of migrants’ vulnerability while employed under a TMP is the requirement that they work solely for the employer specified on their work permit. Migrants may then find it difficult or impossible to escape unsatisfactory working conditions (unless they are willing and financially able to return home). This problem may be exacerbated by some employers’ illegal practices of retaining migrant workers’ passports and providing “tied accommodation”—accommodation provided by the employer on the condition that, and as long as, the migrant keeps working for that employer.

The effective protection of migrants’ rights thus requires at least some portability of temporary work permits, enabling migrants to change employers whenever necessary. As mentioned above, however, it is important to recognize that immediate, complete, and unlimited portability—across all occupations and sectors of the host country’s labor market—would undermine the alignment of the size and composition of economic immigration with what is likely to be a sector-specific demand for migrant labor. In addition, this may substantially reduce the propensity of local employers to recruit migrant workers because the latter would be free to leave the employer who recruited them before at least part of that employer’s recruitment costs have been recovered.

A more realistic policy objective would be to facilitate the portability of temporary work permits within a defined job category and after a certain period of time. The duration of the period after which permits become portable requires a realistic assessment of the time needed for employers to cover at least part of their basic migrant worker recruitment costs. Arguably, this period is unlikely to exceed six months. In this connection, it is crucial to note that it may not be desirable for employers to receive a guarantee that they can recover all their migrant worker recruitment costs. Such a policy could significantly reduce the risks associated with hiring migrant workers relative to those associated with recruiting local workers (who may leave the employer anytime, also before the employer’s investment in the workers has been recovered). This, in turn, could encourage employers to recruit migrant workers over local workers.

The Right to Family Reunion

Although migrants do not have an unrestricted right to family reunion under the CMW, the protection of the family is covered by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 23). So any restriction of this right needs to be based on strong arguments. I believe that the trade-off between openness and this particular right in temporary labor immigration programs, especially in those targeting low- and medium-skilled migrant workers, does provide justification for some restrictions—but within limits.

It is important to distinguish between two types of restrictions on the rights to family reunion: an absolute restriction that does not allow family reunion under any circumstances, and a conditional restriction that grants the right to family reunion to those labor migrants who can provide proof that their incomes are sufficient to ensure that the family member or dependent will not become a fiscal burden on the state—that is, will not create net fiscal costs for the host country’s welfare state. The latter conditional right raises the difficult and in practice highly contested question of how to define “fiscal burden on the state,” and thus where to set the minimum income threshold required of the labor migrants to be eligible for bringing in a family member or dependent.26

As demonstrated in earlier chapters, the extent to which the right to family reunion can be restricted is likely to be a key consideration in how open a particular country is to admitting labor migrants, especially low- and medium-skilled workers. Insisting on an unrestricted right to family reunion, particularly, for low- and medium-skilled migrants, is likely to result in fewer opportunities for workers to access the labor markets of higher-income countries. As chapter 6 has shown, there are a large number of people—some with and others without families in their home countries—who currently choose to work abroad without the right to family reunion. It is also relevant to consider that there are many citizens who choose to take up jobs that in practice take them away from their families for extended periods of time.

The main principles of my normative approach require a balancing of rights with consequences along with a consideration of the agency and choices of migrant workers that we currently observe in practice. For these reasons, I believe that a limited restriction on the right to family reunion can be morally justified. I am opposed to a complete denial of the right to family reunion (apart from seasonal programs that recruit migrants for a few months only), but support policies that impose restrictions based on a minimum earnings threshold that the labor migrant must meet in order to be eligible for bringing in a family member or dependent. At what level this income threshold should be set will vary across countries and hence needs to be debated in a transparent way.27 The costs arising from family members’ likely use of welfare benefits and public services, including the costs of education for children, are in my view legitimate considerations when deciding on this minimum income threshold. In some countries, this conditional restriction of family reunion will exclude many but not all low-skilled (and thus low-paid) guest workers from family reunion.

Time-Limited Restrictions of Rights and Access to Permanent Citizenship

Is there a limit to the period of time for which restrictions on the rights discussed above can be morally justified? I agree with Carens (2008) and many others who have argued that the passage of time increases the strength of migrants’ moral claims to equality of rights. While my normative approach can be used to justify the selective restrictions of migrant workers’ rights for a limited period of time, it does not support policies that create a group of second-class residents who are permanently excluded from equal access to citizenship rights. So a key question is: How long can migrants’ rights justifiably be restricted? As Carens (ibid., 422) suggests, philosophical reflection cannot provide a clear answer. I consider four years a reasonable time period, although I recognize that it is hard to justify why it should not be three or five years. Anything less than three years seems to me “too short” to ensure that the policy generates the intended benefits for receiving countries as well as migrants and their countries of origin, while restrictions that last longer than five years seem to come close to “long term” or “permanent exclusion” from equal citizenship rights—something that I reject.

Let’s suppose we agree on an acceptable period of time for which the rights of migrant workers admitted under a TMP can be restricted. What should happen at the end of this period? Should migrant workers be granted access to permanent residence (and thus, eventually, citizenship)? In important recent contributions to the ethics of immigration policy, Carens (ibid.), Alex Reilly (2011), and Patti Tamara Lenard and Christine Straehle (2011) have all maintained that migrants admitted under TMPs should be granted eventual access to permanent residence status and therefore citizenship. While I can see how this conclusion can be defended as a logical extension of the assertion about moral claims to equal citizenship rights increasing over time, I am concerned—within my normative approach—that the requirement to grant eventually all temporary migrants access to permanent residence and citizenship would significantly lower receiving countries’ incentives to admit some migrant workers—especially low- and medium-skilled workers—in the first place. The requirement to grant eventual access to equal rights means that all the net costs that the temporary restrictions are aimed at minimizing might eventually have to be borne by the receiving country. While some receiving countries may consider it in their national interests to ultimately grant permanent residence to migrant workers admitted under TMPs, this is unlikely to be the case for all countries.

Given these concerns, I argue that there must be a time limit (four years, for instance, as I have proposed above) after which receiving countries need to decide whether to grant temporary migrant workers access to permanent residence or require them to leave. A policy option that I reject is the renewal of temporary work permits with restricted rights for longer than that limit. One way of implementing such a policy would be to operate a points-based system that uses transparent criteria for regulating the transfer of migrant workers from temporary residence status with restricted rights to permanent residence status with almost equal rights.

Enabling Workers to Make Considered Choices before and after Migration

Respecting the agency and choices of prospective and current migrant workers is a core consideration that underlies as well as informs my normative approach in general, and the justifications of the rights restrictions discussed above in particular. For rights restrictions to be acceptable, it is critical to have policies in place that protect agency and enable migrants to make informed, rational choices about both participating in and—equally important—exiting from a temporary labor immigration program. This requires at least three types of policies in migrant-receiving countries.

First, migrants’ legal rights, including the limits of any rights restrictions, must be effectively protected and enforced. This requires strict penalties against employers, recruitment agencies, and any other agents in the migration process who violate laws and regulations setting out rights for migrant workers in immigration, employment, recruitment, and other areas. The protection of migrant rights also requires effective mechanisms of redress for migrant workers who feel that they are denied their legal rights.

Second, to make considered choices, workers considering becoming temporary labor migrants must be provided with good information about the conditions of employment and residence while working under a TMP abroad, including clarity about any restrictions of their rights. In practice, workers obtain information from a wide range of sources including networks of friends, families, and other workers who are already working abroad. While governments are clearly not the only supplier of information about the conditions of employment and life for temporary migrant workers, the fact that their temporary migration policies restrict some of the rights of migrant workers does, in my view, create a special obligation to ensure that the “terms of the deal” are transparent, easily accessible, and made clear to workers before they join the program. There must be “truth in advertising.”

Third, receiving countries’ policies must effectively protect migrant workers’ “exit options”—meaning migrant workers’ ability to leave their employers and exit from the TMP altogether. This requires policies that ensure that migrant workers do not become trapped in the host country because, for example, they were charged excessive recruitment fees that need to be repaid and prevent them from considering a return to their home countries.

Making Temporary Migration Programs Work

To complete my normative assessment of TMPs that selectively restrict the rights of migrant workers, I need to address a question that many people consider to be at the heart of the debate in migrant-receiving countries, especially when it comes to policies for admitting low- and medium-skilled migrant workers: Is it possible to design and implement new and/or expanded temporary labor migration programs for low- and medium-skilled migrant workers in a way that delivers the intended benefits for the migrant-receiving country yet avoids the adverse consequences that such programs have often generated in the past?

There is no doubt that many of the past large-scale temporary labor migration programs, most notably the Bracero program in the United States (1942–64) and Gastarbeiter program in Germany (1955–73), failed to meet their stated policy objectives and instead generated a number of adverse, unintended consequences. From the perspective of the receiving countries, the two most important adverse impacts included: the emergence of labor market distortions along with the growth of a structural dependence by certain industries on the continued employment of migrant workers, and the nonreturn and eventual settlement of many guest workers. The slogan “there is nothing more permanent than temporary foreign workers” has been a popular summary of the perceived failure of past guest worker programs.28

Managing Employer Demand for Migrant Labor

The key to addressing the issue of unintended labor market distortion is to recognize that, if the goal is to generate net benefits for the economy and country as a whole, temporary labor immigration programs, especially those for admitting low- and medium-skilled migrant workers, cannot be designed based on the needs and interests of employers alone.

Employer-led labor immigration policies often become special interest policies that give significant influence to recruitment agencies and the “migration industry.” Employers, migrants, and intermediaries clearly benefit from increased migration, but the admission of more migrant workers may not always be in the best interest of domestic workers as well as the economy and society as a whole. To be sustainable, labor immigration policies need to be based on the national interest, which, I contend, involves balancing the interests of all affected parties, including those of domestic workers.

The practical implication is that employer demand for migrant labor needs to be critically evaluated, and then actively managed and regulated by the state. An argument that employers commonly make when asking for new or expanded temporary labor immigration programs is that migrant workers are needed to fill “labor and skills shortages,” and “to do the jobs that domestic workers will not or cannot do.” It is an important task for governments to critically assess this claim and design policies that create the right incentives for employers. There are three issues that need to be scrutinized and debated: the definition of labor shortages; the feasibility and desirability of the alternatives to immigration as a way of responding to shortages; and the incentives that employers face when recruiting migrant workers.29

Labor shortage is a highly slippery concept. The existence of unfilled job vacancies does not, by itself, indicate that there are labor shortages that would justify the admission of migrant workers. There are several reasons, including the fact that there is no universally accepted definition of a labor shortage. Employers may claim there is a shortage if they cannot find local workers at the prevailing wages and employment conditions, and most media reports of shortages are based on surveys that ask employers to report hard-to-fill jobs at current wages and employment conditions.

In contrast, a basic economic approach emphasizes the role of the price mechanism in bringing markets that are characterized by excess demand or excess supply into equilibrium. In a simple textbook model of a competitive labor market, where supply and demand are crucially determined by the price of labor, most shortages are temporary, and eventually eliminated by rising wages that increase supply and reduce demand. Of course, in practice labor markets do not always work as the simple textbook model suggests. Prices can be “sticky,” and whether and how quickly prices clear labor markets both depend on the reasons for labor shortages, which can include sudden increases in demand and/or inflexible supply. Nevertheless, the fundamental point of the economic approach remains that the existence and size of shortages depend on the price of labor.30 Most of the industries and occupations reporting labor shortages should have rising relative real wages, faster-than-average employment growth, and relatively low and declining unemployment rates.

If there are labor shortages, is immigration a sensible response? Answering this question requires an assessment of the feasibility and desirability of alternatives to migrants. In theory, at an individual level, employers may respond to perceived staff shortages in different ways. These include: increasing wages and/or improving working conditions to attract more residents who are either inactive, unemployed, or employed in other sectors, and/or to increase the working hours of the existing workforce, which in turn may require a change in recruitment processes and greater investment in training as well as increasing skills; changing the production process to make it less labor intensive by, for example, increasing the capital and/or technology intensity; relocating to countries where the labor costs are lower; switching to the production (provision) of less labor-intensive commodities and services; and employing migrant workers.

Of course, not all these options will be available to all employers at all times. For instance, most construction, health, social care, and hospitality work cannot be offshored. An employer’s decision about how to respond to a perceived labor shortage naturally will depend in part on the relative cost of each of the feasible alternatives. If there is ready access to cheap migrant labor, employers may not consider the alternatives to immigration as a way of reducing staff shortages. Although migrants are often a cost-attractive option for employers, they may not be a sensible choice for the overall economy. There is clearly the danger that the recruitment of migrants to fill perceived labor and skills needs in the short run exacerbates shortages, and thus entrenches certain low-cost and migrant-intensive production systems in the long run, potentially reducing their competitiveness over time.

There is no one right answer to the question of whether immigration, higher wages, or other responses are best in terms of labor shortages. Choosing among these alternatives is an inherently normative concern that requires a balancing of different interests. The implication for the design of temporary labor immigration programs is that there needs to be transparency and debate about the feasibility as well as consequences of the various responses to labor shortages in different sectors and occupations. This debate may sometimes lead to the conclusion that labor immigration, including that of low-skilled workers, is a sensible policy, while at other times the alternatives may be more attractive. There can be no one-size-fits-all answer for all countries and all times—but as noted above, there is a process that one can propose so that any introduction or expansion of a temporary labor immigration program is based on analysis and debate aimed at ensuring that the policy does serve the national interest of the receiving country.

The key policy implication of this discussion is that to make the admission of low-skilled migrant workers benefit the national interest of the migrant-receiving countries, governments need to implement policies aimed at linking the admission of new migrant workers to the needs of the domestic labor market, where these needs are defined in terms of labor shortages and a debate about sensible responses. While there are no best practices for such policies, there are at least three different yet overlapping policy approaches to achieving this goal: labor market tests; expert committees and shortage occupation lists; and economically oriented work permit fees.

Labor Market Tests

Labor market tests are mechanisms that aim to ensure that migrant workers are only admitted after employers have seriously and unsuccessfully searched for local workers to fill the existing vacancies. In theory, labor market tests serve an important function because they are meant to prevent employers from recruiting migrant workers over available and suitable local workers. In practice, however, such tests have proved notoriously difficult to implement, not least because employers have shown considerable ingenuity in ensuring that no local workers are found to fill their vacancies when it suits them.31 In the worst-case scenario, both employers and local workers are actually not interested in engaging in employment relationships. This could happen, for example, when employers have a predetermined preference for employing migrant workers and local workers prefer to live off unemployment benefits rather than accept low-wage jobs. Certainly, without the right incentives and enforcement, any labor market test simply becomes a bureaucratic obstacle that serves neither employers nor local workers.

The weakest form of labor market test involves employers attesting that they have unsuccessfully searched for local workers and will pay migrant workers the prevailing (rather than legal minimum) wages in the given occupation (as is the case, for example, under Tier 2 of the United Kingdom’s points-based system). Labor market tests that rely on employer attestation typically do not involve any preadmission checks (i.e., to see whether or not the employer has actually made efforts to recruit local workers) but instead rely on postadmission enforcement. It is unlikely that attestation-based policies are strong enough to ensure that employers do not use migrant workers to bypass domestic workers.