Labor Emigration and Rights Abroad

The Perspectives of Migrants and Their Countries of Origin

Labor immigration policies are “made” in migrant-receiving countries, but they have important consequences for migrants and their countries of origin. This chapter looks at two interrelated questions. How do high-income countries’ restrictions of labor immigration and migrant rights affect the interests of migrants along with their countries of origin? How have migrants and sending countries engaged with these restrictions in practice?

These questions are of central importance to this book’s analysis because the interests of migrants and sending countries can play a crucial role in supporting, sustaining, or undermining particular labor immigration policies in high-income countries. Understanding how migrants and sending countries are affected by—and respond to—particular restrictions on migration and rights is also critical to any ethical/normative evaluation of particular policy regimes. The ethics of labor immigration policy will be examined in the next chapter.

The discussion in this chapter is divided into two parts. The first explores how emigration and rights impact on migrant workers, and how migrants have in practice responded to the labor immigration policy regimes they face. The second half of the chapter concentrates on the effects for sending countries, and reviews selected examples of major sending countries’ engagements with high-income countries’ policies on the admission and rights of migrant workers.

Migrants: Emigration, Rights, and Human Development

Any study of the impacts of particular labor immigration policies on migrant workers requires a conceptual framework for capturing the multifaceted and multidimensional interests of and outcomes for migrants. The discussion below employs a human development approach.

Building largely on the capability approach developed by Amartya Sen (1980, 1999), human development can be defined as a process of “enlarging people’s choices and enhancing human capabilities (the range of things people can be and do) and freedoms, enabling them to: live a long and healthy life, have access to knowledge and a decent standard of living, and participate in the life of their community and decisions affecting their lives.”1 A capability approach is “people centered” in the sense that it focuses on agency and choice.

The concept of human development is inherently multidimensional.2 Theoretical discussions and empirical applications of the human development approach have identified various different dimensions of well-being and development. Martha Nussbaum (2000), for example, lists central human functional capabilities related to life, bodily health, bodily integrity, senses, imagination, thought, emotions, practical reason, affiliation, other species, play, and control over one’s environment. A World Bank study of how poor people perceive and experience poverty distinguished between material, bodily, social, psychological, and emotional well-being; security; and freedom of choice and action.3 Although Sen has not followed others in trying to identify a definite list of universally applicable capabilities, he has highlighted the importance of basic capabilities such as “the ability to move about,” “the ability to meet one’s nutritional requirements,” “the wherewithal to be clothed and sheltered,” and “the power to participate in the social life of the community.”4

The idea of human development shares a common motivation with human rights. Both approaches “reflect a fundamental commitment to promoting the freedom, well-being and dignity of individuals in all societies.”5 Despite their basic compatibility, however, it is crucial not to conflate human development with human rights. As Sen points out, for instance, although it can support many human rights, the capability approach cannot adequately take account of “process freedoms” such as the right to due process in legal proceedings.6

A key feature of the human development approach, which is particularly significant in the context of this book, is its explicit recognition of the possibility of conflicts and trade-offs between different dimensions of development (or between different components of capability), and the consequent need to engage in public debate and reasoning about how to value and prioritize competing capabilities and objectives. The emphasis on the need for valuation and public debate of the potential trade-offs distinguishes the human development approach from both traditional economic approaches that focus on income as the only measure of well-being and human rights approaches that consider rights indivisible, and therefore find it more difficult to engage in debate about trade-offs and priorities.7 As the UNDP’s (2000, 23) report on human rights and human development argues:

Human rights advocates have often asserted the indivisibility and importance of all human rights. This claim makes sense if it is understood as denying that there is a hierarchy of different kinds of rights (economic, civil, cultural, political and social). But it cannot be denied that scarcity of resources and institutional constraints often require us to prioritize concern for securing different rights for the purposes of policy choice. Human development analysis helps us to see these choices in explicit and direct terms.

In the context of the effects of migration and migrant rights, the human development approach is particularly useful because it can distinguish—and requires critical exploration of the potential conflicts—between the capability to move and work abroad, and the capabilities while working and living abroad.

Access: The Capability to Move and Work Abroad

Because international labor migration is much more restricted than international trade and capitals flows, the wage differences across countries are much larger than differences in commodity prices and interest rates.8 Richard Freeman (2006) estimates that the wages of workers in high-income countries typically exceed those of workers in similar jobs in low-income countries by four to twelve times. A more recent study finds that the ratio of wages earned by workers in the Unites States to wages earned by “identical” workers (with the same country of birth, years of schooling, age, sex, and rural/urban residence) abroad ranges from 15.45 (for workers born in Yemen) to 1.99 (workers born in the Dominican Republic), with a median ratio of 4.11.9 These international wage differences mean that migrants can significantly raise their productivity and make large financial gains from employment abroad. The wage differences and relative income gains are largest for low-skilled workers whose international movement is the most restricted.

Emigration is of course not without financial costs for migrants. These costs can include visas fees, travel expenses, payments to recruitment agencies, and in some cases a range of illegal payments such as bribes and other “kickbacks” demanded by different actors involved in facilitating the migration process. These costs vary considerably across different migration corridors and also across different types of migrants within the same corridor. Legal migration costs can be multiples of monthly earnings abroad.10 If illegal payments are involved, the cost of migrating can in some cases exceed annual earnings.

Although there clearly are some migrants for whom, at least in the short run, the costs outweigh the benefits, the majority of labor migrants can be expected to reap large financial benefits from employment in higher-income countries even after all the costs have been deducted. The increase in migrants’ net earnings (i.e., after deducting any costs) can also lead to increases in the economic welfare of migrants’ families, either directly if they are with the migrant in the host country or indirectly through remittances. There is debate about the impacts of remittances on sending countries as a whole, but there is no doubt that remittances can play a powerful role in improving the living standards and human development of migrants’ families.

While there are relatively few systematic empirical analyses of the impacts of emigration on the human development of migrants and their families, two recent studies by the World Bank (both authored by David McKenzie and John Gibson) provide evidence of the potential benefits for migrants. The two studies evaluate the development impacts of participation by migrants from Tonga and other Pacific Islands countries in the Recognized Seasonal Employer (RSE) program in New Zealand launched in 2007, and the Pacific Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme (PSWPS) in Australia started in 2008. The evaluations of both schemes show large financial benefits—and improvement in a range of human development indicators—for participating migrants and their families in their countries of origin. For example, Tongan migrants participating in the PSWPS in Australia received after-tax earnings of AUD12,200 for six months’ work, which is more than five times greater than their previous incomes for a comparable period in their countries of origin. The migration costs were estimated at AUD6,300. They included payments for half the airfare, passports, police clearance, medical checkups, visas, internal travel within the home country, clothing, accommodation, food, health insurance, transport, and telephone calls while in Australia. Of the remaining AUD5,900, the average Tongan migrant remitted AUD4,600, which led to a 39 percent increase in the per capita household income of the migrants’ family in Tonga.11

In comparison, a Tongan worker’s participation in New Zealand’s RSE (which runs for less than six months) increased per capita household income by about 33 percent.12 In addition to raising household income and consumption, the program has allowed households to purchase more durable goods and led to an increase in child schooling in Tonga. The World Bank’s evaluation of the RSE observes, “This should rank it among the most effective development policies evaluated to date.”13

There is thus a strong economic rationale for workers in low- and middle-income countries—especially low-skilled workers whose international movement is currently the most restricted—to seek better access to labor markets in higher-income countries. Importantly, better access to employment opportunities in high-income countries has the potential to not only increase the economic welfare of workers and their families but also improve other dimensions of human development such as education and health. Based on an in-depth analysis of the impact of migration on human development, in 2009 the Human Development Report concluded that “outcomes in all aspects of human development, not only income but also education and health, are for the most part positive—some immensely so, with people from the poorest places gaining the most.”14 This is why “opening up existing migration barriers” was among the report’s core recommendations for national and international policymakers.

Rights Abroad: Capabilities While Living and Working Abroad

How and to what extent migration improves human development outcomes for migrants critically depends on their legal rights while working and living abroad. As human development is defined as enlarging choice, capabilities, and freedoms, we can generally expect that the economic, social, political, and cultural rights that migrants effectively enjoy will have a positive impact on their human development. For example, the right to public health care and education will promote good health as well as the development of knowledge and human capital. Cultural rights enable migrants to practice their own cultures and traditions. The right to family reunion enables a family life. Access to the welfare state could, among other things, offer support in times of economic hardship. And many employment rights, such as the right to free choice of employment (rather than being tied to specific employers of occupations), can be expected to enable migrants to achieve better outcomes in the labor market.

Conversely, restrictions on migrant rights will lower migrants’ human development gains from employment abroad. The denial of basic rights, such as the right not to have identity documents confiscated and the right to redress if the terms of the employment contract have been violated by the employer, can lead to situations where migrants’ welfare and capability to act become highly dependent on their employer, thereby leading to “unfree” living and working conditions.

Various national and international institutions concerned with migrants have published a large number of reports and case studies documenting how a lack of rights can have highly adverse impacts on migrants’ personal safety, physical and mental health, ability to participate in social life, and outcomes in the labor market. Most academic analyses do not consider specific rights but instead distinguish between the four major types of immigration status: illegally resident, temporary (legal) resident, permanent (legal) resident, and citizen.

Their “deportability” can put illegally resident migrants in a vulnerable position in the host country.15 Some employers may offer illegally resident migrants lower wages and inferior employment conditions, either because they take advantage of migrant’s deportability and/or simply to account for the increased risk associated with employing migrants without legal residence rights. Research by J. Edward Taylor (1992) suggests that cost-minimizing employers will allocate illegally resident migrants to jobs where the expected cost of apprehension is lowest, and that such jobs are likely to be relatively low-skilled ones. Deportability may also impact on migrants’ earnings through mechanisms that are not directly related to employer discrimination. Significantly, illegal residence status may alter migrants’ behavior in the labor market.16 Migrants without the right to reside may, for example, have lower reservation wages than workers with the right to legal residence. The fear of being deported could also discourage migrants from investing in the development of host-country-specific human capital.17 Illegal residence status could also impact on the kinds of social networks that migrants may access, which in turn may affect migrants’ access to well-paying jobs.18

Although not at constant risk of removal, migrants employed on legal temporary work permits in low-skilled occupations may also experience lower earnings because of their immigration status. Temporary work permits for low-skilled workers typically restrict migrants’ employment to the sector and employer specified on the document. Where a change of employer is allowed, a new application for another work permit is usually required. This requirement naturally restricts migrants’ choice of employment in the labor market and may make it difficult to leave jobs offering adverse employment conditions. Furthermore, a temporary migrant’s right to legal residence is usually tied to ongoing employment in the host country. As can be the case with illegally resident migrants, unscrupulous employers may take advantage of temporary migrants’ employment restrictions and offer employment conditions that are lower than those enjoyed by migrants with permanent residence status.

Most of the limited empirical research on the impacts of immigration status on migrants’ labor market outcomes has focused on the effects of illegality. Most studies have been carried out in the United States, especially in the aftermath of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which gave amnesty to undocumented immigrants—about 1.7 million outside agriculture—who could prove continuous residence in the United States since 1982. Francisco Rivera-Batiz (1999) concluded that legalization led to significant wage growth for legalized migrants. Sherrie Kossoudji and Deborah Cobb-Clark (2002) also found that the act had positive earnings effects for legalized migrants, mainly because of increased returns to human capital.19

Most of the existing research confirms the expectation that immigration status and the associated rights (restrictions) can be a significant determinant of migrants’ outcomes within and outside the labor market. Expanding rights thus generally can be expected to have beneficial effects on the economic welfare and human development of migrants and their families.

Migration Decisions and Trade-Offs in Practice

International labor migration can be associated with trade-offs between different dimensions of human development. As shown in chapters 4 and 5, except for policies directed toward the most highly skilled migrant workers, labor immigration programs in high-income countries often present migrants with a trade-off between access to labor markets, on the one hand, and restrictions of some of their rights while working and living abroad, on the other. How have migrant workers responded to and engaged in this trade-off in practice?

At the most fundamental level, the fact that large numbers of migrant workers move to and take up employment in countries that severely restrict migrants’ rights can be seen as an indication—although as discussed further below, not necessarily as stand-alone proof—that many workers are willing to tolerate, at least temporarily, a trade-off between better economic outcomes, such as higher wages and family income, and fewer rights.20 As will be explored in chapter 7, the mere presence of migrant workers in countries with high openness–low rights policies of course does not mean that such policies are in the migrants’ best interests, and therefore desirable or ethical from a normative point of view. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that there is large-scale labor migration to countries that severely restrict migrant rights. Low-skilled labor migration to the GCC countries and Singapore is the most extreme case in point. Despite significant restrictions of their rights while working and living abroad, millions of migrant workers pay substantial recruitment fees and other costs to move to these countries in order to improve their incomes as well as raise the living standards of their families.

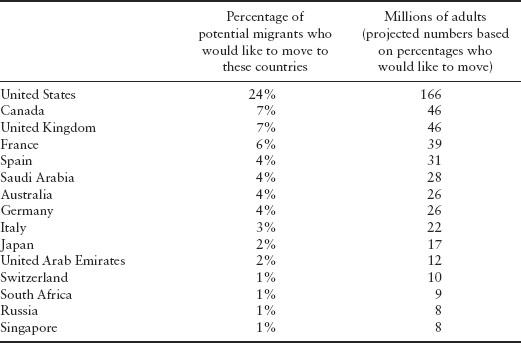

Global survey data confirm that there is an enormous “excess supply” of workers who would like to migrate and take up employment in higher-income countries, including countries where their rights are restricted. A recent global GALLUP survey of adults’ desires to permanently migrate and take up employment abroad found that 15 percent of the world’s adults (seven hundred million people) say that they would like to permanently move to another country if the opportunity arose.21 Unsurprisingly, the most desired movement is from low-to high-income countries. As shown in table 6.1, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore are among the fifteen top-desired destination countries. Saudi Arabia ranks above Australia and Germany, and the United Arab Emirates is a more desired destination than Switzerland.

TABLE 6.1. Top desired destination countries of potential migrants, GALLUP migration intentions survey, 2010–11

Source: Esipova et al. 2011, 3.

Of course, any survey data on desires to move abroad must be interpreted cautiously as most migration desires or intentions do not translate into actual decisions to move. Still, it is interesting that when given the choice to mention any country in the world as their preference, large numbers of adults mention countries that are known to severely restrict the rights of migrant workers.

To what degree can labor migration to countries with restrictions on the rights of migrant workers be discussed in terms of workers making a deliberate choice to trade some of their rights for higher wages and, in many cases, considerable remittances for their families? This question goes to the heart of long-standing debates about the roles and interrelations between agency—the capacity to act independently and make reasoned choices—and structure—factors that limit the choices or opportunities available—in human behavior and decision making.22

For most migrant workers, both factors are likely to be at play. There are clearly important structural factors that impact on and in many ways circumscribe the set of options that individual workers have in their home countries as well as at different points in the migration process (such as departure, movement, or stay abroad). These factors include, for example, the global economic inequalities between different countries and regions of the world, social norms prevailing in home and destination countries, the migration and other policies of nation-states, and the activities of employers and recruitment agencies. The collective interests of families and households may influence individuals’ decisions too.23 Workers with different characteristics, motivations, and resources (e.g., low or high skilled, single or married, living in large or small households, men or women, and employed or unemployed) in different countries (e.g., low or high income), and at different points in time (e.g., during economic growth or crisis) clearly face different structural constraints on the options and opportunities available to them. In other words, the degree of individuals’ agency in decision making about migration is specific to the individuals’ characteristics as well as the time and place. Workers with different characteristics in different countries and situations can also be expected to attach different degrees of importance to the various dimensions of human development. For example, low-skilled workers in Bangladesh may prioritize, at least temporarily, getting a higher-paid job over enjoying access to particular social rights while working abroad in a way that might be unacceptable to a higher-skilled worker in Bangladesh, or even to low-skilled workers in other higher-income countries.

Despite these real and omnipresent structural constraints, international labor migration involves—in most but not all cases—at least some element of choice. Migrant workers are, to put it another way, not simply helpless victims of larger structural forces but to some extent also active agents that make decisions on whether to stay or leave. The degree of choice is variable, and related to the extent to which migration is forced or voluntary. As Thomas Faist (2000, 24) and others have suggested, it is useful to think about the popular distinction between forced and voluntary migration “as a graded scale and not as a dichotomy…. [I]t then makes sense to think of degrees of freedom as ranging from high to low, from involuntary or forced to voluntary.” There are clearly some migrants whose only choice to survive is to leave. This group includes people fleeing from life-threatening persecution (e.g., refugees under the Geneva Convention), or natural disasters such as extreme floods or drought. But the great majority of migrant workers—people leaving with the primary purpose of finding employment abroad—retain some power to decide whether or not to leave (as opposed to forced migration, when migrants do not have this power).24

There is almost always some element of choice even among the poorest and least skilled labor migrants, who typically have the fewest options and are often moving to places that generate the greatest trade-offs between different dimensions of human development.25 This is one of the key conclusions of a recent, rare study of migrant workers’ decisions and rationalizations before, during, and after migration:

Even among the poor, decision-making surrounding whether or not to migrate has to take place. Even after they leave, they have to make decisions about what kind of work to do, how to earn money, whether to send the money home, how much to send, how to send it, as well as whether and after how much time, to go home. Therefore, poverty does not operate in an automatic, unmediated way to simply push people out. People have to decide where to go and, after going, whether to stay away or come home.26

Empirical research concerning the motivations and experiences of different types of migrant workers at various stages of the migration process and in a wide range of countries provides evidence that migrant workers’ decisions are typically (although not always) based on an awareness about the actual and potential trade-offs involved in migration and employment abroad. For example, a study of eastern European migrants working in the United Kingdom before and after their countries joined the European Union in May 2004 found that migrants frequently recognize and rationalize the trade-offs involved in employment abroad.27 Most of the five hundred migrants interviewed worked in jobs that offered low wages and poor working conditions. Working hours were longer than the average for the occupation, and many migrants did not receive paid holidays or written contracts. Many migrants had far more skills than required to do the job, but in contrast to the usual portrayal of bad employer–exploited migrant, most migrants saw themselves as making tough choices and trade-offs. The migrants tolerated low-skilled work and poor conditions because the pay was significantly better than at home, and they could also learn or improve their English. Most important, migrants were prepared for poor conditions because the job was perceived as temporary, with most expecting to eventually move into better jobs or return home. Although sometimes leading to insecurity, the absence of a written contract was not always perceived as disadvantageous.

Choice and awareness of trade-offs are also emphasized by a range of studies of migrant workers employed under guest worker programs, including those that pose significant restrictions on the rights of migrant workers (especially in GCC countries and East Asia). In her review of guest worker programs in a global and historical perspective, Cindy Hahamovitch (2003, 71) concludes that although guest workers have sometime been reduced to slavelike status, “we can still state, though not without some trepidation, that these were exceptions not the rule. Though slavery is alive and well in the global economy of the 21st century … guestworkers are generally volunteers.”

In their study of the experiences of migrant workers in the United Arab Emirates, Sulayman Khalaf and Saad Alkobaisi (1999, 295) observe that “all the migrants now work and live under non-egalitarian conditions, yet it is they who made their own journeys to this global world because they saw and still see opportunities for them lying there to be exploited, and dreams to be realized.” Similarly, Akm Ahsan Ullah’s (2010) study of Bangladeshi labor migrants working in low-skilled jobs in Hong Kong and Singapore demonstrates that migrants’ decisions before, during, and after migration are based on an assessment of a wide range of perceived costs and benefits that go beyond economic concerns, and include, for instance, psychological impacts, especially costs associated with being separated from their children and families.

There also is a considerable body of academic research that suggests elements of choice and awareness of trade-offs in types of labor migration that are popularly discussed in terms of forced migration and/or exploitation. In her book On the Move for Love, for example, Sealing Cheng (2010) discusses the experiences of Filipina migrants who work as entertainers in US military camp towns in Korea. Often depicted as hyperexploited, trafficked persons by the media, governments, NGOs, and international organizations, the book argues that these women have mostly made their choice to migrate with a broad understanding of the likely risks involved in their profession. Cheng contends that migrants have accepted these risks as preferable to the alternative: poverty at home. She (ibid., 11, 222) maintains that “Filipinas make their deployment to South Korea ‘their own,’ as migrant women do not merely obey the call of global capital and leave home as commodified labor or sex objects but are also moved by their capacity to aspire, their will to change, and their dreams of flight,” and calls for “considering their agency in tandem with structural vulnerabilities.”

Migrants who are residing and/or working illegally outside their countries of origin typically experience the most extreme trade-off between employment abroad and rights. As noted earlier in this chapter, illegality is typically associated with few legal rights in the host country. Nevertheless, many high-income countries experience growing populations of illegally resident migrant workers who either entered illegally or overstayed their temporary visas. Illegally resident migrants are vulnerable to a wide range of different types of disadvantages and exploitation—and yet research has shown that illegality in the employment of migrants is the result not only of structural factors (especially income inequality and the immigration policies of receiving countries) but also of the decisions of migrants and their employers.28 There are clearly many workers who consider illegal employment abroad as their best option.

The argument that migrant workers, even those frequently described as experiencing exploitation, are aware of and actively engage in trade-offs between access to higher-paid jobs and restrictions on their rights does not deny that migrants sometimes make decisions based on incomplete or wrong information. Migrants may not be fully aware of the actual wages and living conditions that they are most likely to experience abroad, or they may be victims of unscrupulous employers and/or recruitment agents who engage in “contract substitution,” where migrants agree to specific wages and conditions before departure, and then are presented with a new contract with worse terms and conditions after arrival in the host country. For example, Ullah’s (2010) qualitative study shows how in some cases, the premigration perceptions about potential trade-offs are correct in the sense of materializing once migration takes place, while in other places they are incorrect in the sense that expectations about, say, wages, housing, and life abroad are not realized in the host country. In this study, most Bangladeshi respondents in Hong Kong justified their migration decision and continuing stay by the fact that they earned ten to fifteen times more than was possible in their own country. Half the respondents in Hong Kong said that their initial migration decision was correct in the sense that it was based on information that turned out to be broadly accurate. In contrast, only a minority of the study’s respondents in Malaysia said that their initial migration decisions were correct. They rationalized their continued stay in Malaysia with the hope of recouping the unexpectedly high costs they had incurred in financing their migration. The way in which employment abroad is rationalized thus can change after migration because the facts have changed—which is why assessments of how migrants rationalize their decisions cannot rely on the revealed preference argument alone.29

While some migrants undeniably make choices that they might not make if they had better information, it is hard to claim that this applies to the majority of migrant workers. Migration is critically influenced by networks between communities in sending and destination countries, which help provide information for workers considering a move for the first time. Moreover, a considerable share of migrant workers employed under significantly restricted rights comprises repeat migrants in the sense that people engage in circular migration between their home and destination country. Circular migrants who return to their destination countries make this choice based on the experiences and information gained from previous employment abroad.

A key factor that helps explain the choices that migrant workers make, both at the point of deciding whether to stay or move abroad as well as while working abroad, is migrants’ “dual frame of reference”—the idea that migrants—especially those recently arrived and intending to stay temporarily—compare the conditions of their employment and life abroad to standards in their home countries rather than to those enjoyed by citizens of the host country. As Michael Piore (1979, 54) asserts in his classic work Birds of Passage, as many new migrants’ social identity remains located in their place of origin, “the migrant is initially a true economic man, probably the closest thing in real life to the Homo economicus of economic theory.” Employers are often acutely aware of the different frames of reference among different groups of migrants, which helps explain why migrant workers, especially those working in low-waged jobs, are frequently praised by employers as having a superior “work ethic” compared to domestic workers.30

Trade-offs between access and rights are also increasingly recognized by many NGOs concerned with defending the interests and rights of migrant workers. For instance, Daniel Bell and Nicola Piper (2005) found that NGOs representing domestic helpers in Hong Kong and Singapore were reluctant to promote equal rights for fear of sharply reduced admissions. Manuel Pastor and Susan Alva make a similar argument in the context of the US debate on guest workers. Activists and migrant advocates traditionally oppose guest worker programs, but according to Pastor and Alva (2004, 94), “behind the scenes, there was some support for such a guest worker program, including one based on a certain hierarchy of rights, ranging from those considered baseline for humane existence, such as labour protections, to more extensive provisions, such as the rights to vote, that might be more reasonably limited.” The scholars contend that the main reason why some activists have begun to support guest worker policies is the perceived transnational existence of many migrants, so that they are moving between countries with different rights.

Sending Countries: Interests and Policy Choices

The remainder of this chapter discusses the interests of lower-income migrant-sending countries with regard to the labor immigration policies—openness, selection, and rights—of high-income countries. The analysis below first looks at this question in theory: What does research about the effects of emigration tell us about what sending countries’ interests might be with regard to how high-income countries regulate immigration and the rights of migrant workers? This is followed by three empirical examples of how sending countries have engaged with high-income countries’ labor immigration policies, including trade-offs between access and rights in practice.

Before this exploration, though, it is important to emphasize three crucial contextual points about the constraints on and determinants of labor emigration policy. First, along with being constrained by a wide range of factors in their power to restrict immigration, nation-states face even greater constraints on their formal authority and power to regulate labor emigration as well as the rights of migrant workers abroad.31 While there is no right to migrate to any specific country, there is a human right to leave and return to one’s country of origin or citizenship.32 While exit controls were common in the past, they have been on the decline, and there are now few countries that still use them.33

At the same time, countries can and do implement a wide range of policies that are aimed at influencing the scale and composition of labor emigration as well as the rights of their workers abroad. Examples of such policies include: the promotion of “labor export” through the establishment of government departments tasked with facilitating recruitment and employment abroad; bilateral recruitment agreements with immigration countries; regulation of the recruitment industry; direct lobbying of foreign governments and/or through supra- and international institutions; and a range of diaspora engagement policies such as the extension of dual citizenship rights and the right to vote in the home country while residing abroad. The effectiveness of these policies in influencing the scale, type, and conditions of labor emigration and employment abroad is variable, and depends on a range of factors that are specific to the country and time.

A second important point to underscore is that just like immigration policy, a range of constraints and factors circumscribe the available policy space for regulating labor emigration. For instance, the prevailing political system (e.g., democratic versus nondemocratic states) and historical relationships with receiving countries will influence the availability as well as effectiveness of specific policy instruments. So we can expect significant differences in the policy space for regulating labor emigration across countries and over time.

Third, as is the case with immigration policy, the extent to which “the state” exercises agency plus is in a position to formulate and implement policies based on a given set of objectives varies across countries and over time. We know that in practice, different parts of the state may have different interests and different aspects, and dimensions of emigration policies are not always consistent. For example, in his analysis of the determinants of Mexico’s policies toward emigration to the United States, David Fitzgerald (2006, 260) argues for a “ ‘neopluralist’ approach disaggregating ‘the state’ into a multilevel organization of distinct component units in which incumbents and other political actors compete for their interests.”34 My defense of a national interest approach to the analysis of emigration policies mirrors the argument I made in my conceptualization of immigration policy in chapter 3. Any emigration policy needs to be justified in terms of basic functional imperatives of the state that are reflected in broad policy objectives (the national interest) that countries can and do formulate as well as pursue in practice. As the discussion in this chapter will show, many sending countries clearly do articulate and attempt to pursue national policy objectives with regard to labor emigration and the rights of citizens abroad, so it makes sense to analyze policies in light of an examination of their national interests.

Sending Countries, Emigration, and Migrant Rights: What Can We Expect?

Low-income countries have strong economic incentives to send more workers to take up employment in higher-income countries. The World Bank estimates that increasing the share of migrants in high-income countries by 3 percent would generate a global real-income gain of over $350 billion, exceeding the estimated gains from global trade reform by about 13 percent.35 If migrants transfer some of their benefits back to their home countries—in the form of remittances, investments, and/or knowledge transfers—migrant-sending countries may reap a significant share of these global gains from migration. According to the World Bank, remittance flows to developing countries amounted to about US$351 billion in 2011 (more than triple the figure from 2002).36 Global remittance flows are more than twice as large as the total development aid and represent the largest source of foreign exchange for numerous countries.

It is important to emphasize that more emigration does not automatically translate into faster development within migrants’ countries of origin. The effects of remittances, and emigration more generally, can be mixed in both in theory and practice.37 Research and the experiences of countries experiencing large-scale emigration—such as Egypt, Mexico, and the Philippines—suggest that sending workers abroad cannot, on its own, be an effective development strategy.38 Yet it is clear that, if used effectively, remittances and other transfers migrants make back to their home countries can be of significant benefit to migrants’ families and/or the overall economies of migrants’ countries of origin.

Regarding selection policies, there are three economic reasons why we can expect low- and middle-income countries to particularly favor the liberalization of international flows of low-skilled workers. First, low-income countries have relatively more low-skilled workers and the international wage differentials between low-skilled workers are significantly higher than those between skilled workers.39 The liberalization of low-skilled migration consequently would generate greater global efficiency gains than that of skilled migration. A related point is that the emigration of low-skilled workers can be expected to raise the wages of nonmigrant low-skilled workers in migrant-sending countries.40 This would increase the economic welfare of the lowest-income earners rather than those of skilled and highly skilled middle- and high-income earners, and thus decrease inequality in poor countries.

Second, in some but not all low- and middle-income countries, the emigration of skilled workers can create significant costs because of the training and other investment in the migrant along with, more generally, the decline in productive capacity. Costs of this brain drain are likely to be particularly pronounced in small countries with relatively underdeveloped public health care and other sectors that require skilled workers. For example, more than 80 percent of the tertiary educated workforce in Suriname, Jamaica, and Haiti has emigrated abroad.41 It is important to stress, however, that skilled emigration is not always a net drain on the sending country. Some countries aim to produce an oversupply of skilled labor and consider the export of skilled workers as an opportunity rather than as a threat.42 There is also some empirical research evidence to support the idea that high-skilled emigration can, under certain conditions, increase—not decrease—the stock of human capital in sending countries. In theory, this “brain gain” can happen when the future prospect of emigration raises individuals’ incentives to acquire human capital and when only a share of those getting education with a view to future employment abroad end up actually emigrating. Educational institutions’ capacity to expand their training in respond to rising demand is a key condition for this process to work in practice—a condition that is likely to hold only for some countries. A recent review of empirical research indicates some, although relatively weak, evidence supporting the existence of such positive brain-gain effects.43

Third, just as high-skilled migrants can be expected to make a bigger net fiscal contribution than low-skilled migrants in migrant-receiving countries, the emigration of high-skilled workers can be expected to create a greater fiscal loss for their countries of origin than would the departure of low-skilled workers. A recent study of the fiscal impact of high-skilled emigration from India to the United States found that the annual net fiscal impact to India was about 0.5 percent of India’s gross national income or 2.5 percent of India’s total fiscal revenues.44

Finally, what are the potential interests of sending countries with regard to the rights of their nationals working abroad? In principle we can expect any country to strongly want to promote the rights of their workers abroad. Due to economic incentives, however, sending countries, may not always insist on more or equal rights. For one, in high-income countries where labor immigration policies are characterized by a trade-off between admission and rights, an insistence on rights may jeopardize sending countries’ objective of sending more workers abroad. Second, while many rights will improve the human development of both migrants and those “left behind” (family members and/or others) in migrants’ countries of origin, it is important to consider potential exceptions and trade-offs where an increase in certain rights for migrants may lead to a reduction in the benefits of migration for migrants’ countries of origin. Migrants on temporary residence permits, for example—especially those with families in their home countries—can be expected to remit more of their wages than migrants with permanent residence status abroad. Although the overall empirical evidence on this issue is mixed, there is some evidence that remittances initially increase, yet eventually decrease with a migrant’s duration of stay in the host country, reflecting the counteracting forces of wage increases (which increase remittances), on the one hand, and increased detachment from the home country and family reunification (lowering remittances) over time, on the other hand.45 Acquiring the right to permanent residence will benefit migrants’ human development, but the associated decline in remittances (and if migrants are highly skilled, the potential permanent loss of human capital) could lower human development in migrants’ countries of origin. Of course, the impact of rights on remittances is just one type of effect that may be outweighed by other beneficial impacts for sending countries. The research on this issue is limited.

The critical conclusion from these basic theoretical considerations is that while the interests of sending countries can be expected to favor more open admission policies, especially for low-skilled workers, in higher-income countries, sending countries’ interests toward the rights of their nationals working abroad—especially for those rights that are perceived to be inversely related to openness—are much more ambiguous. How sending countries engage with and respond to trade-offs between openness and rights is an important question for empirical research.

A global review of guest worker programs concluded that at least to some extent, all of them involved sending countries that were afraid of insisting on rights of their workers abroad for fear of losing access to labor markets.46 “The more remittances pour into banks, the less inclined sending governments have been to protest too much.”47 The remainder of this chapter reviews four examples of sending countries’ engagements with trade-offs between access to labor markets in higher-income countries and the rights of migrant workers abroad. As was the case in chapter 5, the period under consideration here is 2011, and—unless indicated otherwise—all discussions of policies below refer to policy in or before that year.

Low-Income Countries Sending Migrant Workers to the GCC Countries and Southeast Asia

The trade-offs between openness to labor immigration and migrant rights are most pronounced in GCC countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and in some Southeast Asian countries, such as Singapore and Malaysia. How are countries that are sending large numbers of migrant workers to these countries perceiving and responding to these trade-offs?

TABLE 6.2. Emigration, remittances, and foreign direct investments in major Asian sending countries, 2010

Source: World Bank 2011.

The majority of migrant workers employed in GCC countries and Singapore are from Asian countries, many of which are heavily dependent on labor emigration and remittances (see table 6.2).

Most sending countries in Asia have created specific government departments tasked with working toward two objectives: promoting labor emigration and remittances; and protecting the rights and welfare of migrants abroad. There is a widespread perception that these two aims are often competing. According to Piyasiri Wickramasekara (2011, 31), one of the foremost experts of Asian labor emigration, “Origin countries in Asia are generally confronted between the dilemma of promotion and protection.” This dilemma is reflected in the formal labor emigration strategies and plans recently developed in various countries. For instance, the Sri Lanka National Labor Migration Policy enacted in 2008 makes the trade-off explicit: “Thus, the delicate balance between the promotion of foreign employment and the protection of national workers abroad is a continuous challenge.”48

Some countries’ official emigration strategies make it clear that more labor emigration and remittances are given priority over the more effective protection of the rights of migrant workers. In Pakistan, say, the first-ever National Emigration Policy (enacted in 2009) identified fifteen priority areas, almost all of which were concerned with sending more workers abroad (especially to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) and facilitating remittances rather than the protection of rights. Furthermore, migrant rights advocates have pointed out that “priority area 12” of the plan, which deals with protecting the right of emigrants, includes important measures such as predeparture training as well as more help lines and counseling at embassies abroad, but does not mention any formal engagements at the diplomatic level with receiving countries about the rights of migrant workers. A recent review of Pakistan’s emigration policy concluded that it is “short of any state-to-state high-level dialogue initiative for emigrants’ rights advocacy and for awareness raising and mobilization of migrants for their rights in the destination countries.”49

Although there are some variations in different sending countries’ labor emigration policy approaches and bargaining power vis-à-vis specific host countries, it is clear that all the major Asian countries sending workers to the Middle East and Southeast Asia are concerned that too much emphasis on migrant rights may come at the cost of reduced or, in the worst-case scenario, no access to the labor markets of these countries. The fear of losing access to markets and the consequent adverse impact on remittances has been found to be among the main reasons why some major sending countries in Asia have been reluctant to sign the CMW.50 The Philippines, which has arguably been more active on rights protection than other countries in the region, was the first major Asian sending country to ratify the convention in 1995. Bangladesh signed the convention but did not ratify it until 2011. Indonesia signed in 2004 yet ratified the convention only in 2012. Pakistan has not ratified it. A UN review of the reasons for the nonratification of the CMW in 2003 (when Bangladesh and Indonesia had not ratified it yet) concluded that Bangladesh and Indonesia “are afraid of losing jobs abroad and of other sending countries picking up their workers’ share if they ratify the ICMR [CMW].”51

The use of and experiences with labor export bans by the Philippines, Indonesia, and other countries are a good example of how major sending countries struggle to balance the twin objectives of sending more workers abroad and protecting their rights. The Philippines has a long history of labor emigration and is a major recipient of remittances. As such, promoting emigration has become a core part—and some argue the core feature—of the country’s overall economic strategy. According to Walden Bello (2011), congressperson and chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Overseas Workers Affairs, “Our foreign policy has been reduced to one item: promoting the export of our workers and securing their welfare abroad.”

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) has a dual mandate: to promote and develop the overseas employment program and protect the rights of migrant workers. Its legal mandate includes a requirement to restrict the official deployment of Filipino migrants to countries that provide adequate protection of the rights of migrant workers.

Section 4 of the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995, as amended by the Republic Act No. 10022 in 2009, states that:

the State shall allow the deployment of overseas Filipino workers only in countries where the rights of Filipino migrant workers are protected. The government recognizes any of the following as a guarantee on the part of the receiving country for the protection of the rights of overseas Filipino workers.

(a) It has existing labor and social laws protecting the rights of workers, including migrant workers;

(b) It is a signatory to and/or a ratifier of multilateral conventions, declarations or resolutions relating to the protection of workers, including migrant workers; and

(c) It has concluded a bilateral agreement or arrangement with the government on the protection of the rights of overseas Filipino Workers:

Provided, That the receiving country is taking positive, concrete measures to protect the rights of migrant workers in furtherance of any of the guarantees under subparagraphs (a), (b) and (c) hereof.

In the absence of a clear showing that any of the aforementioned guarantees exists in the country of destination of the migrant workers, no permit for deployment shall be issued by the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration.52

The act further clarifies that the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) issues “certification” to the POEA, “specifying therein the pertinent provisions of the receiving country’s labor/social law, or the convention/declaration/resolution, or the bilateral agreement/arrangement which protect the rights of migrant workers.”53

In May 2011, the POEA, based on advice from the DFA, approved seventy-six countries for the continuing deployment of Filipino migrant workers.54 The POEA also asked the DFA to further review and reevaluate the countries not included on the list. In October 2011, after this review, another forty-nine countries were added to the list of compliant countries, thus open for the deployment of Filipino migrants.55 At the same time, the POEA announced a ban on the deployment of migrant workers to forty-one countries that the DFA found to be noncompliant with the guarantees stipulated in the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act.

Some migrant rights advocates were critical of this ban as it only included countries that received only a small number of migrant workers from the Philippines.56 Others—including the DFA itself—were concerned about potential adverse impacts on relations with these countries including a potential backlash toward Filipino workers currently employed in these countries.57 Soon after the list of banned countries was published, the DFA asked the POEA for a ninety-day reprieve “to provide enough time to work on the possible bilateral agreements with the 41 countries, enabling them to comply with the requirements of the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act.” In early November 2011, the POEA recalled Resolution 7, which announced the ban, and granted the ninety-day reprieve.

Importantly, by late 2011 key destination countries in the Persian Gulf states (including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain) as well as Singapore had not been included on any of the published lists of eligible and banned countries. Instead, these countries were identified as “conditionally compliant” in late 2011, and the DFA continued to assess them. They were given a grace period of six months (i.e., longer than the three-month grace period offered to those countries on the noncompliant list), “giving some countries in the Middle East and other countries a chance to amend their laws to ensure the protection of our OFWs [Overseas Filipino Workers].”58 According to an official at the DFA in October 2011, “We are not shutting the door to any host country but paving the way to reach a bilateral agreement and strengthening the diplomatic ties between the Philippines and the host countries. We do not want to antagonize them.”59 Congressperson Walden Bello made it clear in November 2011 that “we are trying to balance safety and livelihood.”60

On May 22, 2012, the POEA issued a resolution that added thirty-one countries, including Singapore, to the list of compliant nations.61 Through another resolution issued on June 28, 2012, the POEA deemed the previously partially compliant and noncompliant thirty-two countries as “compliant without prejudice to negotiations for the protection of the rights of household service workers and/or other categories of workers for the purpose of continuing deployment to these countries.”62 The resolution further noted that the “POEA may continue deployment to these countries and DFA will continue to negotiate for the better protection of household service workers even beyond 12 April 2012.”63 The new and expanded list of eligible, compliant countries (184 in total) now includes all the key Persian Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates).

The Philippines’ experience with labor bans shows that while the Philippines government is clearly concerned about the rights of its migrant workers abroad, there appears to be a strong policy view that the more effective protection of rights must not come at the cost of significantly reduced access to labor markets in the GCC and some Southeast Asian countries.

Indonesia’s recent experience with labor bans has been similar to that of the Philippines. Indonesia has used temporary labor bans since 2009. Kuwait has been banned since 2009, Jordan since 2010, and Syria since 2011. Malaysia was banned in 2009, but the ban was lifted in 2011. Although the Indonesian government announced in March 2011 that it had no further plans to make additions to its list of banned countries, it decided to impose a moratorium on labor export to Saudi Arabia in June 2011.64 This was in response to the continuing rights abuses of Indonesian migrants in Saudi Arabia, including the beheading of an Indonesian maid as punishment for killing her employer in Saudi Arabia in June 2011. The Indonesian government said that the moratorium would only be lifted after the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the two countries to help safeguard the basic rights of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia. The moratorium was going to become effective on August 1, 2011, but Saudi Arabia announced in late June 2011 that it was banning domestic workers from Indonesia and the Philippines, citing demands for better terms of employment by the two countries.65 Saudi Arabia consequently stopped issuing work visas to domestic workers from both these countries, and announced that it would make greater efforts to bring domestic workers and other migrant workers from other countries.66 In July 2011, Saudi Arabia lifted a two-year embargo on recruiting Bangladeshi workers.

In late 2011 and early 2012, both Indonesia and the Philippines were negotiating the possibility of memorandums of understanding and bilateral agreements with Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries. In both countries, many activists have been critical of the ban. For example, Dedeh Elah, an activist from the Cianjur Migrant Workers Union, said that “instead of imposing the moratorium, it would be better for the government to provide better protection for Indonesian workers abroad, and improve training standards.”67

The making and unmaking of labor export bans make it clear that the trade-off between encouraging labor emigration and protecting migrant workers’ rights is at the heart of the overall policy approach and strategies adopted by the Philippines, Indonesia, and other Asian sending countries. Some sending countries are obviously concerned about the rights of their nationals working abroad, but the overriding priority has remained the promotion of more labor emigration and remittances. As a result, despite public demands and government rhetoric emphasizing the importance of protecting rights, in the end most sending countries have continued to trade rights restrictions for continued access to labor markets in GCC and some Southeast Asian countries.

A key challenge for any individual sending country is that GCC and other migrant-receiving countries in the region can easily mitigate the effects of any unilateral policy decision by a sending country to stop sending workers by turning to other, often lower-income countries for recruiting more workers. So there is a collective action problem. If one country complains about rights violations there has—so far—always been another country that is happy to step in and send migrant workers. The Colombo Process, aimed at helping unite major sending countries in their negotiations with major receiving countries in Asia, has “yet to graduate from an information-sharing platform to a bloc that can develop a common bargaining position in negotiations with labor-receiving countries.”68

Sending Low-Skilled Workers to the United States and Canada: Perspectives of Latin American Sending Countries

The tension between the policy goals of maintaining or increasing labor emigration, on the one hand, and protecting migrant rights, on the other, has also been one of the primary dilemmas for Latin American (and other) countries sending migrant workers to the United States and Canada. While the rights restrictions involved in these trade-offs are qualitatively different from those observed in the Middle East (i.e., liberal democracies are less likely to restrict basic civil rights), the limited research on sending countries’ interests in this region demonstrates that there is a clear perception of competing objectives: promoting labor emigration versus the protection of rights. As is the case with Asian countries sending migrant workers to the Gulf, the available evidence suggests that for Latin American countries, the perceived need to maintain or expand access to North American labor markets has frequently trumped the more effective protection of migrant rights, especially for low-skilled migrant workers.

Most of the eighty-eight respondents interviewed in Mark Rosenblum’s (2004) study of the emigration policy preferences of policymakers in Mexico and other Central American countries, for example, described the impacts of emigration as involving a trade-off between political-economic benefits and sociopolitical costs for migrants as well as their countries of origin. In these interviews, policymakers identified remittances and jobs as the top two perceived benefits from emigration, while the top two perceived concerns were human rights/exploitation and “family/cultural issues.” Rosenblum (ibid., 104) concluded that “the informants essentially saw emigration as a necessary evil: supplying needed short-term and economic benefits but also imposing immediate human and cultural costs and hindering long-term development.”

Mexico’s “policy of nonintervention” in labor emigration to the United States in the second half of the twentieth century—most of which was illegal—can be interpreted as another case of a major sending country giving more priority to continuing labor emigration over more effective protections of its migrant workers abroad.69 The share of Mexican emigrants in the United States within the total Mexican population rose from less than 2 percent in the 1950s to over 10 percent in the 2000s.70 Since the end of the Bracero program—a bilaterally negotiated guest worker program for sending Mexican farmworkers to the United States—in 1964, most labor migration from Mexico to the United States has been illegal. The estimated stock of the “US unauthorized immigrant population from Mexico” was 4.6 million in 2000 and 6.7 million in 2009.71

In the early 2000s, the Vicente Fox administration (2000–2006) attempted to negotiate a new guest worker program and legalization for undocumented Mexicans in the United States—negotiations that were abandoned after the September 11, 2001, attacks. These negotiations marked the first formal steps that the Mexican government took to proactively engage with labor emigration and emigrants in the United States since the end of the Bracero program.72 For most of the second half of the twentieth century, the Mexican government tacitly acquiesced to a trade-off between continuing labor emigration to the United States at the cost of the restricted rights that are a natural consequence of illegal status. Alexandra Delano (2009, 770) explains this policy approach in the following way:

Mexico has been highly dependent on the continuation of emigration—through formal or informal channels—as a “safety valve” for economic and political pressures and, more recently, as a key source of income for remittance recipients…. In general, [the] Mexican government has tried to maintain a relatively disadvantageous but stable status quo in order to guarantee the continuation of the flows…. Thus, despite continued abuses and discrimination against Mexican workers, violations of contacts, and the costs of emigration, particularly for some regions, the government generally maintained a “policy of no policy” that included limited reactions to US migration policies and legislation.

The tension between promoting labor emigration and protecting migrant rights has also been at the core of Mexico’s and the Caribbean countries’ engagement with Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), which started in 1966. SAWP provides Canadian farmers with temporary migrant workers during the planting and harvesting seasons.73 While the program used to be dominated by Jamaican men, the majority of participants are now Mexican workers. Migrants’ stay is limited to a maximum of eight months, after which workers need to return to their home countries. In practice the majority of SAWP workers participate in the program over many years. SAWP is based on bilateral agreements between Canada and participating sending countries, which are responsible for selecting and recruiting workers for participation in the program. As Canadian growers can specify their preferred supply country, they can engage in “country surfing” for the best workers.74 Consequently, sending countries are in direct competition with each other for the number of places made available to their nationals under the program. According to Jenna Hennebry and Kerry Preibisch (2009, 9), sending countries are “eager to capture workers remittances and ease unemployment at home, invest significant resources in recruitment and selection of workers, as well as providing liaison staff in Canada.”

Sending countries compete in terms of the skills, perceived quality, and reliability of their workers as well as in terms of the services made available to Canadian growers, such as delivering workers quickly and just in time for production.75 For example, the Mexican Ministry of Labor asks Canadian growers to complete end-of-year evaluations for each worker, and the assessments are used to determine that worker’s future eligibility for the program—a policy that is plainly aimed at promoting labor discipline.76

As is the case with Asian countries sending workers to the Gulf, there is also evidence that countries sending workers to Canada under SAWP are prioritizing continued or expanded access to the program over the effective protection of rights. The trade-off between access and rights is played out and “personified” in the role of the government liaison officer of the source countries in Canada. According to the official website for SAWP, when a Canadian employer violates the contract’s terms, “workers should first contact the government liaison officer of their source country in Canada.” Yet in addition to helping resolve disputes with employers and assisting workers whose rights have been violated, the government liaison officer is supposed to maximize the access for workers from their country to Canadian growers. These dual objectives can create a conflict of interest:

Employers state that their choice of supply country for workers is determined in large part by the level of service that a consular office will provide. The Government Agents understand that they are in competition for worker placements on farms and therefore, have to be responsive to employers, and they were all aware that if a dispute is not resolved, a grower may select workers from another country.77

Clearly, the competition between sending countries for access to Canada’s SAWP means that government liason officers balance their efforts to maintain or improve access to growers with efforts to protect migrant rights. Much to the frustration of workers advocacy groups in Canada, sending countries thus have not always been among the most outspoken supporters of the rights of their workers employed under SAWP. As one liaison officer interviewed by Preibisch and Leigh Binford (2007, 24) suggested, “[Voicing rights] causes some employers to switch, because a lot of them don’t want backchat or voicing of rights.”

Access versus Equal Treatment in the EU Posted Workers Directive

Instituted in 1996, the EU Posted Workers Directive (Council Directive 96/71/EC) requires that workers “posted” by an employer in one EU member state to temporarily work on a project in another member state should be guaranteed the minimum employment conditions of that second country.78 A posted worker is defined in the directive as “a worker who, for a limited period, carries out his work in the territory of a Member State other than the State in which he normally works.” Posted workers exclude independent labor migrants, self-employed migrants, and seafarers. The directive thus applies only to workers who are temporarily posted abroad by their companies.

The directive has two primary objectives. The first is to promote the free provision of services across EU member states by removing uncertainties about the applicable legal standards when posting workers abroad. The opening of the directive states that “the abolition, as between Member States, of obstacles to the free movement of persons and services constitutes one of the Objectives of the community.” The second aim is to provide protection of minimum conditions of employment. The directive notes that “a ‘hard core’ of clearly defined protective rules should be observed by the provider of services.” In the context of this book, these two goals can be interpreted as relating to promoting openness to migrant workers (in this case, the provisions of services by migrants) and the protection of minimum rights.

The two objectives are clearly competing, especially since 2004, when the European Union was expanded to include eight eastern European countries with substantially lower average wages than those prevailing in the “old” (i.e., pre-2004 enlargement) EU member states. The objective of the free provision of services across EU member states suggests that member states should be able to freely provide their services to other member states without having to comply with that country’s labor standards. The spirit of this aim implies that member states with lower wages and labor costs should be able to make use of their comparative advantage and supply their services at “competitive prices” to other higher-wage member states. At the same time, the objective of protecting minimum employment conditions suggests a desire to protect workers in any EU member state from being undercut by cheaper workers with fewer rights who are posted by companies based in other EU member states. It essentially boils down to the well-known conflict between labor standards and free trade, which in the context of the European Union has frequently been discussed as a conflict between service liberalization versus the “European social model.”79

Given these dual and competing objectives, the question of how to define the minimum terms of conditions of employment that posted workers should be subject to is at the core of the directive, and as mentioned below, has been at the center of recent disputes about the meaning and implications of the directive. Article 3(1) of the directive defines minimum conditions as laid out by the host country’s “law, regulation or administrative provisions,” and/or by “collective agreements and arbitration awards.” These conditions may refer to: maximum work periods and minimum rest periods; minimum paid annual holidays; minimum rates of pay; the conditions of hiring out workers; health, safety, and hygiene at work; protective measures for the employment of pregnant women, women who have recently given birth, and children as well as young people; and equality of treatment between men and women.

The implications of these minimum conditions, and the Posted Workers Directive more generally, were at the heart of the “Laval dispute,” which was eventually settled by a ruling of the European Court of Justice in 2008. As already discussed in chapter 5, this case involved a Latvian construction company (Laval) winning a public tender to renovate a primary school near Stockholm. Laval paid its posted workers almost double the going wage rates in Latvia, but less than the collectively agreed-on wage for the sector in Sweden. The Swedish trade union took collective action and blocked all Laval sites in Sweden. Laval initiated proceedings in the Swedish courts in an attempt to have the Swedish trade unions’ actions declared unlawful. After the Swedish courts ruled in favor of the trade union, Laval took the case to the European Court of Justice, which eventually ruled in favor of Laval. The court ruled that the Swedish unions’ boycott constituted a violation of the principle of the free movement of services as the unions’ demands exceeded the minimal national employment protections under Swedish national laws. The judgment was a victory for supporters of greater liberalization of service provisions across EU member states, and a blow to supporters of the protection of the rights and labor market regulations prevailing in some of the old EU member states.

How did the Latvian government view and engage with this case? In a nutshell, it strongly supported Laval, and was engaging with the Swedish government, Swedish trade unions, European Court of Justice, and other relevant parties to the dispute at the highest diplomatic level. As a new EU member state with some of the most neoliberal policies, Latvia was keen on arguing the broader case that the insistence of labor standards in the old EU member states should not become a stumbling block to expanding the provision of services across EU member states.

A few days after the Laval disputed started, the Latvian deputy foreign minister met with the Swedish ambassador to discuss the case, maintaining that Sweden should be supporting and enforcing the free movement of services across the European Union.80 Latvia’s foreign minister made it clear that the Swedish response “goes against our understanding of why we joined the EU.”81 The Latvian government then set up an interministerial working group headed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and involving representatives of the ministries of the economy, justice, and welfare. A few months later the Latvian prime minister talked about the issue with the Swedish prime minister at an EU summit in Brussels, and wrote a letter to the European Commission’s president expressing his concern. The Latvian government also stated at that point that it might take the issue to the European Court of Justice.

Most of the other new EU member states—which shared an interest in prioritizing the liberalization of the service provisions across EU member states over the protection of labor standards in the old member states—strongly supported the Latvian government’s position in the Laval dispute. When considering the Laval case in 2007, the European Court of Justice invited submissions from all EU member states. As analyzed by Nicole Lindstrom (2010), government submissions clustered around new and old member states. The new member states (joined by the United Kingdom and Ireland) contended that the Swedish trade unions’ actions were not compatible with the free movement of services (Article 49) or the Posted Workers Directive, while most of the old EU member states strongly defended the rights to take industrial action as well as enforce national wage agreements and social policies more generally. In other words, Latvia and most other new EU member states were pushing for better access to the labor markets of the old EU member states, which in contrast, were defending their labor standards, which effectively acted as a restriction on the employment of migrants at a lower cost. Lindstrom (ibid., 1307) concluded that “with the ECJ ultimately ruling with the employers and against the expressed preferences of most old Member States and unions, the rulings furthered the cause of liberalization in the enlarged EU, but also mobilized political opposition.”

Wage Parity as a Stumbling Block within GATS Mode 4 Negotiations

The tension between openness and equality of rights is also at the heart of the negotiations within the WTO’s GATS Mode 4 framework. The GATS negotiations aim to liberalize the international movement of service providers. Services move across borders in four major ways or modes. Mode 1 cross-border supply occurs when the service rather than the supplier or consumer crosses national borders. Call centers are an example. Mode 2 involves the consumption of a service abroad when the consumer travels to the supplier. For instance, a patient travels abroad for medical services. Mode 3 relates to a “commercial presence,” which reflects the international movement of capital, such as when a bank or other global company sets up a subsidiary in another country. Finally, Mode 4 involves the movement of “natural persons.” The provider of the services in this case temporarily moves to the consumer in another country.

Through a system of “commitments” by WTO member states, GATS aims to achieve greater liberalization of the provision of services across borders. This technically involves each of the 153 WTO member states making specific commitments with regard to reducing market access barriers for each of the four modes of service supply. It is possible and standard practice for member states to link their commitments to various conditions. One of the most commonly used condition and barrier in member states’ scheduling practices is to tie Mode 4 commitments to Mode 3. The majority of all Mode 4 commitments are connected to Mode 3 investments—meaning that they require a commercial presence of a foreign service supplier. Another key barrier is the requirement of wage parity, which means that foreign service providers need to be paid the prevailing wages given to similar workers in the country where the service is provided. As is the case under the EU Posted Workers Directive, the purpose of the wage parity requirement—and other related, frequently used requirements such as minimum wages along with work and social security benefits—is to protect workers in high-income countries from declining wages and what is sometimes viewed as unfair competition from low-cost service providers.82