An Empirical Analysis of Labor Immigration

Programs in Forty-Six Countries

This chapter analyzes the key features of labor immigration programs in high and middle-income countries in practice. I construct and scrutinize two separate indexes that measure the openness of labor immigration programs in forty-six high- and middle-income countries to admitting migrant workers, and the legal rights (civil and political, economic, social, residency, and family reunion rights) granted to migrant workers admitted under these programs. The term labor immigration program refers to a set of policies that regulate the admission, employment, and rights of migrant workers. Most but not all countries operate multiple and different labor immigration programs for admitting different types of migrant workers. The analysis distinguishes between programs that target low-, medium-, and high-skilled migrant workers. In addition to providing an international comparative data source for identifying the primary features of labor immigration policies, the indexes facilitate an empirical study of the three hypotheses about the relationship between openness, skills, and migrant rights developed in chapter 3.

It is important to emphasize at the outset that the construction of any index poses a number of methodological challenges and necessarily relies on numerous assumptions. The use of policy and rights indexes in particular can be contentious as they aim to provide quantitative measures of complex issues that do not easily lend themselves to the kind of simplification and rigid description associated with an index. The approach in the analysis below is to be as open and transparent as possible about the methodology along with its limitations, and carefully explain all the assumptions and decisions made at various stages of the analysis. The first half of the chapter explains the methodology, and the second half presents the empirical results. The aim is to make an initial contribution to the debate about an issue that has so far received little systematic empirical analysis.

Existing Research and the Scope of My Analysis

Indexes of Immigration Policy and Migrant Rights

There is considerable academic and policy literature that comparatively discusses labor immigration policies in different countries, but few studies have constructed indexes to systematically measure policy differences across and/or within countries.1 The exceptions include studies by Lindsay Lowell (2005) and Lucie Cerna (2008), both of which focus on policies toward highly skilled migrant workers in about twenty countries, and Ashley Timmer and Jeffrey Williamson (1996), who constructed an index to study immigration policy change during 1860–1930 in six countries. Most recently, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) carried out an assessment of migrant admissions, treatment, and enforcement policies in twenty-nine developed and developing countries.2 The ongoing IMPALA (International Migration Policy and Law Analysis) project aims to measure immigration policies in twenty countries over time.3 Some broader public policy indexes include limited evaluations of immigration policy as a subcomponent.4 There are also more narrow indexes focusing on asylum policies.5

Despite the increasing interest in measuring human rights, there are also few studies that systematically measure the scope and variation of the legal rights of different types of migrants across high-income countries.6 Notable exceptions include Harald Waldrauch’s (2001) work, which constructs a “legal index” that measures the integration of migrants in six European countries, and the more recent Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which uses a mix of legal and outcome indicators to measure policies for integrating migrants in EU member states and three non-EU countries.7 Specifically, MIPEX measures the extent to which each country’s policies conform to European directives and European standards of best practice in six areas: labor market access, family reunion, long-term residence, political participation, access to nationality, and antidiscrimination. The migration policy indexes developed by Lowell (2005), Cerna (2008), and Jeni Klugman and Medalho Pereira (2009) also include an evaluation of a small number of migrant rights.

The indexes constructed in this project differ from existing indexes on immigration policy and migrant rights in four major ways. First, they have a more clearly defined focus on rights and openness than most existing indexes. Although some migrant rights are captured by some of the existing indexes (e.g., some of the indicators used in MIPEX, the Migrant Accessibility Index, and the UNDP’s policy assessment measure some legal rights of migrants), none of the existing indicators were designed to measure the rights of migrant workers. Similarly, the focus on openness, straightforwardly interpreted as the degree to which a country restricts the admission of different types of migrant workers, is less ambiguous as well as easier to conceptualize and measure than “competitiveness,” as used in some of the existing studies. Second, the indexes developed and analyzed below differentiate between low-, medium-, and high-skilled migrant workers, thereby facilitating analysis of the variation of rights and policies according to skill, and the interplay among rights, skills, and openness. Third, rather than mixing policy and outcome indicators, the index of rights in this project centers on the legal rights granted by national laws and policies to migrant workers after admission. Although this approach has some limitations (discussed below), it has the advantage of more clearly measuring the rights granted to migrants by law and regulations in the host countries. Finally, the indexes developed in this project cover a larger number and broader range of high- and middle-income countries than existing studies.

Countries, Programs, and Skills

The analysis includes all high-income countries (i.e., those with gross national incomes [GNI] per capita that exceed US$11,905 in 2008, as defined by the World Bank) with a population exceeding two million, and, to ensure broad geographic coverage, a selection of upper- and lower-middle-income countries. In total, the sample comprises forty-six countries, including thirty-four high-income countries (thirty states in this group are upper-high-income countries defined by me as states with GNI per capita exceeding US$20,000 in 2008), nine upper-middle-income countries, and three lower-middle-income countries (China, Thailand, and Indonesia). The complete list of countries is shown in table A.1 in appendix 1.

In most but not all countries, migrant workers are admitted under various different labor immigration programs (e.g., many countries operate different policies for low- and high-skilled migrants), which are typically associated with different sets of admissions criteria and rights for migrant workers. The units of my analysis are thus labor immigration programs rather than countries as a whole. The period under consideration in this chapter is 2009, and—unless indicated otherwise—all discussions of policies here refer to that year. Altogether, the analysis includes 104 labor immigration programs, or an average of 2.3 programs per country. This average masks considerable variation. Some countries, such as Sweden and Belgium, only operate one major labor immigration program. In contrast, the United States has six different programs for admitting migrant workers, while Canada and Australia each have four.

To explore the potential variation of openness and rights across labor immigration programs that aim to admit migrants with different skills, each of the programs included in the analysis is assigned one or more targeted skill levels. The targeted skill level of a labor immigration program reflects the skills required in the (specific or range of) jobs that migrants are admitted to fill. It also allows for the common phenomenon of skilled migrant workers taking low-skilled jobs abroad. Just because a particular labor immigration program aims to attract low-skilled migrant workers (for low-skilled jobs) does not necessarily mean that in practice, higher-skilled migrants will not apply and be admitted to fill the jobs. There is considerable evidence showing that skilled migrants often do lower-skilled work in high-income countries. This particularly applies to new (i.e., recently arrived) migrants, who sometimes view their first job abroad as a stepping-stone to a better job that more closely corresponds to their skills.8

The analysis distinguishes between four broad skill levels: low-skilled (LS), defined as migrant workers with less than high school education and no vocational skills; medium-skilled (MS), defined as migrants with high school, vocational training, or trades qualifications, such as electricians, plumbers, and so on; high-skilled (HS1), defined as migrants with a first degree from a university or the equivalent tertiary training; and very high-skilled (HS2), defined as migrants with second-or third-level university degrees, or equivalent qualifications. These distinctions are necessarily artificial and not always directly applicable, as immigration policies may define skills in terms of education, occupation, work experience, and/or pay of the job in the host country. Some flexibility and judgment is required when assessing what types of skill levels specific programs are designed to target.

Importantly, some programs may target more than one skill level. Sweden, for example, has one common labor immigration program that is open to admitting migrants of any skill level. The United Kingdom has two programs: Tier 2 of the United Kingdom’s points-based system admits medium- and high-skilled workers, whereas Tier 1 admits very highly skilled workers only. In the United Kingdom there are currently no programs for admitting low-skilled migrant workers from outside the European Union.

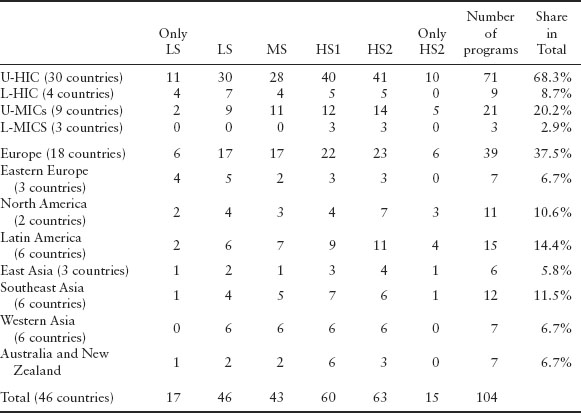

Table 4.1 gives an overview of the targeted skill levels of the labor immigration programs analyzed in this chapter, by income classification and region. Over three-quarters of all programs are in high-income countries, and over 40 percent are in Europe. Table A.1 in appendix 1 indicates the skill levels that are targeted by all the immigration programs in all the countries in the sample. The sample includes twelve seasonal programs, most of which are in Europe and target the admission of low-skilled migrant workers only.

Types of Migrants Not Covered by the Indexes

It is crucial to emphasize that as this chapter is concerned with legal labor immigration and the rights of migrant workers, the discussion focuses on labor immigration programs that admit migrants for the primary purpose of employment. The analysis excludes various other groups including: migrants admitted for the purpose of study, family union or reunion, or humanitarian protection; migrants admitted under various channels that include an employment component but not as the primary purpose of immigration, such as au pair programs and “working holidaymakers”; migrants admitted under specific work-related immigration programs that are internationally negotiated (such as “intracompany transfers,” which are regulated by GATS Mode 4) and/or that do not treat migrants as employees (e.g., programs that admit self-employed migrant entrepreneurs); and migrants who entered and/or are working illegally in the host country.

TABLE 4.1. Labor immigration programs in the sample, 2009

Notes: U-HIC: upper-high-income countries with GNI per capita exceeding US$20,000 in 2008; L-HIC: lower-high-income countries with GNI per capita less than US$20,000 in 2008; U-MICs: upper-middle-income countries; L-MICs: lower-middle-income countries; onlyLS: programs that target only low-skilled workers; LS: programs that target low-skilled workers and possibly others; MS: programs that target medium-skilled workers and possibly others; HS1: programs that target high-skilled workers and possibly others; HS2: programs that target very high-skilled workers and possibly others; onlyHS2: programs that target very high-skilled workers only.

Of course, many migrants not admitted for the primary purpose of employment may nevertheless take up work in the host country and eventually become classified as migrant workers. This analysis is only concerned with migrants who are admitted as workers rather than for other reasons. This choice can be justified on two grounds. First, there is significant variation in the considerations that inform high-income countries’ policies for regulating the admission and rights of migrant workers, students, family members/dependents, asylum seekers, and refugees. Economic considerations are likely to have a greater impact on labor immigration policies than, for instance, on asylum policies, where humanitarian considerations can be expected to play a bigger role. This chapter’s analysis of the relationship between labor immigration policy and the rights of migrant workers cannot be expected to automatically apply to migrants who have not been admitted for the purpose of employment. A second and related reason is the complexity of the project: including other categories of migrants in the index would make an already-complicated measurement and analysis even more involved.

The discussion also excludes migrants admitted under free movement agreements such as that operating among EU member states. For EU countries, the index only includes policies toward non-EU (third-country) nationals. Under the European Union’s free movement directive, a citizen of any EU member state has the right to freely migrate and take up employment in any other EU member state without any restrictions. In other words, EU member states are fully open toward admitting migrants from other EU member states, and are also obliged to grant them most of the rights of citizens (except for the right to vote in national elections). There are three reasons why migrants who benefit from free movement agreements are excluded from the analysis. For one, although significant in some countries, free movement agreements account for a minority of international labor migrants moving to most high- and middle-income countries. There are, however, some exceptions. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2009, labor immigration from within the European Union (which increased significantly since EU enlargement in May 2004) was eighty-six thousand compared to fifty-four thousand from outside the European Union.9 In most other countries, free movement migration accounts for a much smaller share. Across the European Union as a whole, citizens of other EU member states constitute about a third of all migrants.10 Second, most free movement agreements cannot be considered labor immigration policies as they are typically part of larger harmonization policies or regional projects that involve a wide range of policies as well as objectives (e.g., free trade and investment policies). A third and related point is that free movement agreements are mostly one-off policies that are difficult or impossible to reverse without changing the nature of or membership in the wider policies. For example, by implementing the free movement directive, EU member states have effectively relinquished control over the admission of other EU nationals. Unilaterally imposing restrictions on the admission and employment of EU nationals would be extremely difficult politically, and might require leaving the European Union altogether.

It is important to keep the exclusion of the groups described above in mind when analyzing and interpreting the results of the labor immigration policy indexes in this chapter. Depending on the country, high- and middle-income countries’ policies toward the groups excluded from this analysis are potentially significant for explaining the labor immigration programs and policy choices analyzed in this chapter.

Indicators for Measuring Openness to Labor Immigration

The openness index aims to measure the degree to which labor immigration programs restrict the admission of migrant workers. A program with a high (low) degree of openness is characterized by few (many) restrictions on the legal immigration and employment of migrant workers. The indicators of the index thus aim to capture the presence and, whenever relevant, relative strength of particular restrictions. In principle, it is desirable to aim for a relatively small and parsimonious set of indicators. At the same time, it is important to identify a set of indicators that is broad enough to allow for different “modes of immigration control”—that is, different types of policies that regulate the admission of migrant workers. Different countries with different welfare states, production structures, and industrial relations systems can be expected to operate different types of restrictions on labor immigration. The set of indexes must be broad and flexible enough to capture this variation.

To conceptualize and identify the relevant indicators of openness, it is useful to broadly distinguish between three types of restrictions: quotas; criteria that employers in the host country need to meet to legally employ migrant workers (“demand restrictions”); and criteria that potential migrant workers need to meet to be admitted to the host country (“supply restrictions”). This distinction is obviously somewhat artificial as some restrictions may, for example, affect both demand and supply. Nevertheless, it is a useful general approach to identifying the relevant indicators. The overall openness index comprises a total of twelve indicators, each of which is briefly discussed below (for a list of openness indicators, see appendix 2).

Quotas

The most direct way of restricting labor immigration is through quotas: numerical limits set by the government on annual immigration or net-migration flows, or on the stock of migrants, either expressed in absolute numbers or as a share of the population or labor force of the host country. In practice, quotas can take a variety of forms. They could constitute “hard” annual caps that cannot be surpassed (i.e., the government stops admitting migrants when the quota is reached), or “soft” target levels that can be exceeded and therefore act as a guide rather than as a fixed ceiling on the annual number of admissions (as is the case, say, for Canada’s programs for admitting skilled migrant workers). Quotas may be set for the country as a whole (for example, the H-1B program for recruiting skilled and specialized migrant workers in the United States); the country’s various regions or administrative districts (see, for instance, Switzerland’s Auslaenderausweis B program for issuing one-year work permits); or certain sectors of the economy, for specified occupations, and/or individual employers or enterprises (e.g., Singapore imposes sector-specific “dependency ceilings” that specify the maximum share of foreign workers with work permits in the total company workforce). For the purpose of this index, the quota indicator distinguishes between hard quotas that are relatively small (the most restrictive type), hard quotas that are relatively large (where the distinction between small and large is based on the share of the quota in the population), soft quotas, and no quotas (the most open policy).

Demand-Side Restrictions

Job offer. Most temporary work permit programs, such as the United Kingdom’s Tier 2 program or Ireland’s work permit program, require migrants to have a firm job offer before they can be admitted to the host country. In these programs it is typically the prospective employer rather than the migrant worker who initiates the work permit application process. In contrast, permanent labor immigration programs and some temporary ones for highly skilled migrants do not strictly require a job offer. For example, Canada’s Federal Skilled Migrant Worker Program, Australia’s Skilled Independent Visa Program, and New Zealand’s Skilled Labor Immigration Program are all permanent immigration programs that admit skilled migrants without a job offer. All these programs, however, grant applicants with job offers extra points in their points-based admissions processes. Denmark’s green card scheme and the United Kingdom’s Tier 1 program are examples of temporary labor immigration policies that admit highly skilled migrants without a prior job offer. Designed to attract the “best and brightest” in the global competition for talent, both programs allow migrants to look for employment after they have been admitted on an initially temporary basis, but with an opportunity to upgrade to permanent status after a few years (five years in the United Kingdom, and seven years in Denmark). For the purpose of this index, the indicator “job offer” distinguishes between programs that do not admit migrants without a job offer (the most restrictive policy); do not strictly require a job offer, but use it as a factor influencing admission; and programs where a job offer does not influence admission at all (the most open policy).

Labor market test. Many—but not all—temporary work permit programs operate labor market tests, which aim to ensure that employers recruit migrant workers only after having made every reasonable effort to recruit local workers (where local is defined differently across countries).11 The rationale of labor market tests is to protect the employment prospects of the resident workforce. Most labor market tests require employers to advertise their vacancies in the domestic labor market for a minimum period of time. One can broadly distinguish between two types of labor market tests: a relatively weak test based on employer “attestation,” and a stronger test based on “certification.” Attestation-type tests simply require employers to attest that they have unsuccessfully searched for local workers without any checks by a government agency (or other institution) into the employers’ local recruitment efforts before the migrant is admitted. Tier 2 for admitting skilled workers under the United Kingdom’s points-based system operates on this basis. Reflecting a “trust-the-employer approach,” attestation requirements are a relatively weak restriction as they are usually associated with limited enforcement measures after the admission of the migrant workers.12 In contrast, labor market tests that are based on certification require employers to obtain confirmation/certification from a particular body—typically a public employment agency—that the requirements of the labor market test have been met before the work permit application for employing a migrant worker can be submitted. In Ireland, for instance, employers are required to obtain a certificate from the public employment service (FÁS) to certify that they have advertised the vacancy and that no local workers were matched to the job before they apply for a work permit. The labor market test indicator in the openness index distinguishes among very strong certification-based labor market tests in all sectors/occupations covered by the program (the most restrictive policy); strong certification-based labor market tests, but with some sectors/occupations exempted (e.g., through shortage occupation lists that include jobs where the government suspends the labor market test requirement because of a known shortage of domestic workers); weak attestation-based tests; and no labor market tests (the most open policy).

Sectoral/occupational restrictions. It has become increasingly common for labor immigration programs to be restricted to specific sectors and/or occupations in the host country. Many countries, for example, operate specific programs for the seasonal employment of migrant workers in agriculture.13 The index distinguishes between programs that restrict the employment of migrants to specific sectors and/or occupations (the restrictive policy) and those that do not (the open policy).

Economic work permit fees. All programs that admit migrants on the basis of a job offer require employers to pay administrative work permit fees. Some countries—most notably Singapore and Malaysia—also charge employers economically oriented fees as a way of “micromanaging” employers’ incentives and the recruitment of migrant workers. Singapore’s so-called foreign-worker levies are payable by the employer per migrant employed. The levies are flexible (i.e., regularly revised), specific to the migrant’s skill level and sector of employment, and rise with the share of migrants employed at a company. For example, in 2008 the monthly levy for employing a skilled migrant in Singapore’s construction sector was S$150; the corresponding levy for employing an unskilled construction worker from abroad was S$470, which was equivalent to just under 20 percent of the average monthly wages in the sector at the time.14 The economic fees indicator distinguishes between programs that charge employers economic fees (the restrictive policy) and those that do not (the open policy).

Wage restrictions. Restrictions on the wages and other employment conditions at which migrants must be employed can constitute a powerful limit on the legal inflow and employment of migrant workers. One can broadly distinguish between three types of wage restrictions, ranging from the most open to the most restrictive. The most open policy is to simply require migrants to be employed at the legal minimum wage (if one exists) prevailing in the country. In a few countries in the Middle East, certain types of migrants are exempted from minimum wage legislation. The great majority of countries analyzed here are liberal democratic countries that all require employers to pay migrants at least the minimum wage. The most restrictive policy is to require employers to comply with wages and employment conditions stipulated in collective wage agreements. Such agreements are common in coordinated market economies, and they are strongest in the Scandinavian welfare states of, say, Sweden and Norway. In Sweden, any employer who wants to legally employ migrant workers must do so in strict compliance with prevailing industrial standards as determined by collective agreements. As will be discussed in chapter 5, this requirement has been a major factor why Sweden has seen few labor migrants from outside the European Union over the past three decades despite having an immigration policy that is relatively open on many other policy components. An intermediate policy on wage restrictions, operative in many countries including the United States and the United Kingdom, is to require employers to pay migrants the average or prevailing wage in the relevant occupation and/or sector. What constitutes the prevailing wage is typically highly contested, and that in turn is why this policy is a significantly weaker requirement than having to pay collectively agreed-on wages.

Trade union involvement. The sixth and final demand-side restriction considered by the openness index relates to the involvement of trade unions in individual work permit application processes. Representing resident workers in host countries, trade unions can be expected to have an interest in ensuring that immigration does not adversely affect the wages and employment conditions of domestic workers. Although not all trade unions are opposed to immigration, in countries with strong collective agreements and wide union coverage, trade unions have often played a major role in limiting the number of migrant workers admitted.15 For example, before Sweden’s immigration policy reform in late 2008, any application for a work permit for non–European Economic Area (EEA) workers had to be approved by the relevant Swedish trade union.16 In some other countries, unions do not have veto power, yet they still exert some influence over individual applications. Under Canada’s programs for the temporary employment of low-skilled migrant workers, for instance, employers in certain sectors must consult unions as part of the process of obtaining a “positive labor market opinion” (a certification requirement) before the work permit application can be processed. Similarly, in Taiwan, employers wishing to recruit low-skilled migrant workers must notify and consult the relevant trade union, and provide full details about the job vacancy. The trade union indicator thus distinguishes among programs where unions have strong, some, or no involvement in individual work permit application processes.

Supply-Side Restrictions

Nationality and age restrictions. The personal characteristics of migrants can be factors limiting or influencing their admission under labor immigration programs in high- and middle-income countries. An increasing number of bilateral labor immigration programs are restricted or give preference to migrants from particular countries. Spain’s Contingente program for low-skilled migrants, for one, is based on a series of bilateral recruitment agreements with a small number of countries including Ecuador and Morocco. Restrictions by migrants’ age are less common, but nevertheless can be an important factor in certain countries. Singapore requires low- and medium-skilled migrants to be under fifty years of age. Under most points-based systems for managing labor immigration, including in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, age is a factor that influences the admission of migrant workers. The indicator capturing restrictions based on nationality and/or age distinguishes among four types of restrictions, in order of increasing openness: programs that limit admission by both nationality and age; those that restrict admission by nationality or age; policies where admission is influenced (but not restricted) by nationality and/or age; and programs where age and nationality do not affect admission.

Gender and marital status restrictions. In a relatively small number of countries, gender and marital status are factors restricting or influencing the admission of migrant workers. In Saudi Arabia, for example, all women including migrants are prohibited from carrying out certain “hazardous” activities. Marital status can matter under points-based systems that grant extra points for the skills of spouses—as it is the case, say, under Australia’s policies for admitting skilled migrants on a permanent basis. The indicator reflecting gender and marital status restrictions includes the same distinctions of different types of restrictions as the indicator capturing nationality and age restrictions.

Skills requirements. Skills requirements are common and not restricted to labor immigration programs that target skilled and high-skilled migrant workers. The term skills is ambiguous, and can be interpreted and operationalized in many different ways. It could refer to education, qualifications, work experience, and other competencies. For the purpose of this index, the indicator measures whether skills requirements are an explicit criterion for admission, and if so, how specific these requirements are. The most open policy is one that does not specify any skills requirements. A weakly restrictive policy specifies a generic minimum skills threshold such as “vocational training,” “completed high school,” or “university degree.” For example, under Germany’s labor immigration program for admitting skilled migrant workers, residence permits are granted to “professionals with a recognized degree or a German equivalent foreign degree.” A strongly restrictive policy uses generic minimum skills requirements plus specific and explicit skills as a criterion influencing but not restricting admissions. This is the case under most points-based admission mechanisms for skilled labor immigration that award points for different levels of academic qualifications (e.g., in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada) and in some countries also for work experience (in Canada). The most restrictive policy on skills restrictions admits only those migrants with specific skills. Denmark’s Positive List labor immigration program, for example, defines a specific set of minimum qualifications for each profession/occupation. Depending on the occupation, qualifications vary, ranging from a professional bachelor’s degree or three years of university studies to a master’s degree, with some occupations requiring “Danish authorization” (e.g., dentists, veterinarians, and marine engineers).

Language skill requirements. In some countries, admission as a migrant worker requires at least some knowledge of the host country’s language. For example, under the United Kingdom’s current points-based system, migrants must have a minimum proficiency of English. A less restrictive policy is to use language skills as a factor influencing although not strictly limiting admission, as is the case, say, under Canada’s and Australia’s policies for admitting skilled migrants on a permanent basis.

Self-sufficiency. Many, but not all, labor immigration programs require migrants to prove before admission that they will be self-sufficient in the host country—that is, that they will not rely on public funds to support themselves and their families. This restriction can take the form of a requirement to demonstrate savings of a certain amount (e.g., workers seeking to enter the United Kingdom as skilled migrants must have £800 in available funds in their bank accounts for three months before the date of the work permit application) and/or evidence of a firm job offer in the host country that pays well enough to avoid dependence on public assistance.

Indicators for Measuring Migrant Rights

The migrant rights index aims to measure the absence/presence and scope of the legal rights (defined here as the rights granted by national laws and policies) granted to migrant workers on admission under a particular labor immigration program. Programs under which migrant workers enjoy more and a wider range of legal rights will score higher than countries with fewer, narrower legal rights for migrant workers.

The emphasis on legal rights means that the index will not measure the enjoyment and experience of rights in practice.17 In theory, migrants can be denied some rights that exist in law (e.g., if there is no effective state protection and enforcement of the existing legal right to a minimum wage) and/or enjoy rights that do not exist in law (e.g., medical doctors may in practice treat patients without the legal rights to health care). Clearly, one would ideally like to measure rights in law and practice, but the latter would involve considerable and complex research that goes beyond the scope of this project.

There are three conceptual issues that are worth highlighting before looking at the specific rights included in the index. First, while the rights of migrant workers are typically more restricted than those of citizens, the legal rights of citizens can and do vary across countries. We may expect many/most liberal democracies to respect the civil and political rights stipulated in international human rights law, yet we are likely to find significant variation in economic and social rights across liberal democracies. Furthermore, high-income countries that are not liberal democracies may not provide their citizens (let alone migrants) all the civil and political rights stipulated by the human rights treaties. It is thus possible, for example, that neither citizens nor migrants have the right to join trade unions. When constructing and interpreting the scores of the index for a particular right it is obviously important—as I have done in this chapter—to also consider whether citizens enjoy that right.

A second and related issue pertains to the meaning as well as nature of different types of rights along with the implications for measurement. The meaning, freedoms, and benefits of some rights are relatively clear and consistent across countries and time, thereby lending themselves to consistent measurement. For instance, the right to free choice of employment generally means that people are free to apply for any job in the country (although the range and quality of jobs available can of course vary significantly across countries). Yet there are other rights—mainly economic and social rights—that primarily relate to equality of treatment rather than to some absolute and universal standard, which makes them more difficult to measure and compare across countries. The right to equal access to public health services is a good case in point. The range and quality of public health services obviously varies significantly across countries. Migrants with the right to equal access to public health care in Argentina and Sweden enjoy the same legal right, but the value of their rights—understood in terms of the actual benefits that the right conveys—differs dramatically across the two countries.

Third, time can play a key role in the analysis of migrant rights. As discussed in chapter 3, there is a general and crucial distinction between migrants with temporary or permanent residence status. In most liberal democracies, migrants with permanent resident status enjoy the same or similar economic and social rights as citizens. The scope for restricting migrants’ rights is largely limited to migrants on temporary residence permits. The policy decision on whether to grant migrants temporary or permanent residence status thus has important implications for opportunities and ease of restricting migrants’ rights.

Time can also matter as a determinant of access to specific rights. While some rights are typically granted (or not) on admission to the host country, other rights are sometimes acquired over time. For example, various countries including Ireland and the United Kingdom operate “habitual residency tests”—that is, minimum residency requirements—to determine eligibility for certain social benefits. The right to family reunion is sometimes granted only after the primary migrant has spent a minimum period of time in the host country. The measurement of rights therefore must allow for the consideration of time as a potential determinant of access to specific rights.

Given these conceptual preliminaries, the migrant rights index developed for the analysis in this chapter comprises indicators for a total of twenty-three different rights, selected and adapted from the CMW. Although greatly underratified (see the discussion in chapter 2), the CMW’s comprehensive list of rights for migrant workers is a useful benchmark for this exercise. Since the emphasis in this analysis is on the rights of regular migrant workers, the indicators are based on rights taken from parts 3 and 4 of the CMW—excluding specific rights to be granted to irregular migrant workers (covered by part 5 of the CMW). It is essential to stress that some of the rights stipulated in the CMW are conditional/qualified and sometimes limited to certain groups. This is critical to keep in mind, but it does not directly affect the choice of indicators.

Following the human rights framework, the index includes a mix of different types of rights including five civil and political rights, five economic rights, five social rights, five residency rights, and three rights related to family reunion. Some of the indicators are measured as binary variables (such as 0 for “no, no legal right,” and 1 for “yes, legal right in place”), while others involve a scale (0–2 with 0 = no legal right, 1 = restricted legal right, and 2 = full legal right in place without restrictions) to indicate restrictions and the degree to which a legal right is available. As explained below, in some cases scales are used to take account of rights that are granted after a certain period of time. Appendix 3 includes the full list of migrant rights indicators used and analyzed in this study.

The index includes five civil and political rights.18 There are two indicators that capture the right to vote and the right to stand for elections in local and/or regional elections (no country offers migrants without citizenship status the right to vote in national elections). Both indicators include a time element to allow for the possibility that the rights to vote and/or stand for election are granted after some time, but without switching into a separate immigration status.19

The right to form trade unions and other associations along with the right to equal treatment and protections before criminal courts and tribunals are both measured relative to the rights of citizens; in both cases, there is an intermediate score of a “limited” right that falls between the extremes of no and equal rights.

The fifth right under the category of civil and political rights captured by the index is the right not to have identity documents confiscated by anyone, other than a public official duly authorized by law. The wording is taken from the 1990 UN convention. In some countries, especially but not only in the Gulf States, it is relatively common for employers to retain migrant workers’ passports. This is generally considered illegal under both international human rights law and in terms of the national laws of the countries issuing the passport, which generally stipulate that passports are the property of the issuing country. The indicator aims to measure the extent to which the retention or confiscation of passports and other identification documents is declared illegal in the domestic laws (e.g., constitutions and/or labor laws) of host countries. In Spain and Mexico, for example, domestic laws explicitly state that migrant workers have the right not to have their documents confiscated.

Economic Rights

The indicators included in the category of economic rights are primarily aimed at measuring migrants’ rights in the host country’s labor market. A key right that is often restricted for migrant workers is the right to free choice of employment in the host country’s labor market. Migrants on permanent work and residence permits typically enjoy this right in full, although some countries impose temporary geographic restrictions in order to retain migrant workers in regions experiencing the most acute labor shortages. For instance, Canada’s Provincial Nominee Program for skilled migrant workers grants permanent residence on admission, but temporarily restricts the migrant’s legal employment to the region that nominated and supported the migrant’s admission to the country. In contrast to permanent residents, temporary migrants’ rights to free choice of employment are typically (although not always) restricted. Most temporary labor immigration programs require workers to work for the employer specified on the work permit only. Where possible, changing employers usually requires a new work permit application.

The right to join trade unions can be an important determinant of a migrant’s bargaining power and security in the labor market. The United Arab Emirates are among the very few countries in the sample that do not have unions (for these countries only, the score thus reflects the fact that there are no unions rather than indicating discrimination against migrants with regard to the right to join unions). In Malaysia, migrants are explicitly excluded from unions. In Kuwait, migrants must have resided in the country for at least five years and must have a valid work permit before they are allowed to join trade unions as nonvoting members.

The other three economic rights included in the index all relate to equal access to the protections and benefits of the host country’s employment laws. They include the right to equal pay as local workers doing the same work, the right to equal employment conditions and protection (e.g., overtime, hours of work, weekly rest, paid holidays, sick pay, health and safety at work, and protection against dismissal), and the right to redress, if the employers have violated the terms of the employment contract.

Social Rights

The social rights indicators measure migrant workers’ rights to equality of access to unemployment benefits, public retirement pension schemes, public educational institutions and services, public housing including social housing schemes, and public health services. As shown in appendix 3, each of these indicators has four possible scores to take account of both time and other limitations. Two variations of social rights indicators have been constructed. One is premised on a scoring system that is strictly based on equality of rights regardless of whether citizens enjoy the rights or not. This means that a score of 1 (“full equality right”) could either reflect complete equality in access to existing social rights or be due to the absence of a particular social right for all residents (citizens and noncitizens). This type of indicator thus measures the extent to which migrants are treated differently, not whether or not there is a particular social right in the host country.

A second, alternative indicator of social rights takes account of the fact that some countries do not provide their own citizens with certain social rights. Where this is the case, the score has been changed to 0 (no right). The advantage of this type of indicator is that it provides an absolute measure of whether migrants enjoy a particular right or not. The disadvantage is that it does not distinguish between countries and programs that do not grant migrants any access to an existing right afforded to citizens and those that do not offer any rights to citizens or migrants without citizenship. The construction of the overall index and analysis of social rights in particular will use both types of indicators of social rights.

Residency Rights

The length and security of residence status granted to migrant workers varies significantly across different labor immigration programs across and within countries. The existence and nature of restrictions on migrants’ right to legal residence in the host country is a key issue that has crucial implications for possibilities for restricting a wide range of migrant rights. The indicator captures four common possibilities of regulating the right to residence. The most restrictive policy is to grant migrants a strictly temporary residence permit with no legal possibility of changing status (“upgrading”) to a permanent residence status. This is common among seasonal migration programs and most general programs in the Gulf States. A less restrictive policy is to grant a temporary residence permit, but with an opportunity—possibly regulated by further selection mechanisms—to obtain permanent residence status after a certain number of years (the indicator distinguishes between programs that allow permanent residence in fewer or more than five years of residence in the host country). The temporary H1-B program for specialty workers in the United States, for example, allows migrants to apply for permanent residence status after six years of employment in the United States. In Ireland, migrants admitted on temporary green cards for highly skilled workers can apply for permanent residence after three years. The most generous policy with regard to migrants’ rights to legal residence is to grant immediate permanent residence rights as is the case, for instance, under Australia’s and Canada’s points-based programs for admitting skilled migrant workers.

Three additional indicators aim to measure the conditionality and, more generally, security of a migrant’s right to legal residence. One of these indicators measures how, if at all, criminal and administrative convictions affect residence status. Depending on the country, different types of immigration offenses may fall under either or both of the two types of convictions. Revocation of the legal right to residence on the basis of administrative convictions alone is considered a more restrictive policy than revocation on the basis of criminal convictions. A separate indicator assesses migrants’ legal right to remedies/redress in case of withdrawal or nonrenewal of residence permit, or in case of a deportation order.

A third indicator of security of residence considers whether and how a migrant’s right to legal residence is affected by loss of employment in the host country. Most TMPs, especially those that grant strictly temporary permits, make the right to residence directly conditional on employment. In other words, loss or termination of employment results in immediate loss of residence rights. Some countries, including Austria and Denmark, allow some migrants on temporary permits who have lost their employment to remain in the country for a limited period of time in order to look for a new job through “bridging visas.” The most liberal policy is to completely decouple employment from residence status—namely, make the right to legal residence independent of whether the migrant is employed or not. This policy is usually reserved for skilled and highly skilled migrants admitted on permanent work and residence permits (e.g., Canada and Australia), but there are also some TMPs that allow migrants to remain for a certain period without a job (e.g., the United Kingdom’s Tier 1 program for admitting highly skilled workers).

The fifth indicator in the category of residence rights relates to access to citizenship. The scores for this indicator are based on whether and after how many years it is possible to naturalize (i.e., obtain citizenship of the host country) on the basis of the immigration status granted under the immigration program under consideration. In other words, it is an indicator of direct access to citizenship rather than indirect access that requires the migrant to switch to another immigration status before applying for citizenship. Generally speaking, most programs that grant migrants permanent residence status immediately on admission also include a path to naturalization. Among temporary programs, some allow for pathways to citizenship (e.g., skilled migrant workers in the United Kingdom), while others do not (e.g., migrant workers in most of the Gulf States).

Family Rights

The final category of indicators included in the migrant rights index relates to family reunion and the spouse’s right to work in the host country. Two indicators measure the right to family reunion. The first assesses whether migrants admitted under a particular immigration program have the right to family reunion, and how extensive the right is in terms of the definition of relatives qualifying as family and/or dependents. Many programs for low-skilled and strictly time-limited labor immigration do not grant migrants any rights for family reunion (e.g., seasonal migrant workers in Austria and Greece). Other programs allow family reunion, but it is fairly narrowly defined (e.g., only spouses and minor children, as is the case in Belgium’s program for admitting labor migrants). The most liberal right to family reunion includes a wider group of family members and dependents, such as grandparents and children over the age of nineteen. For example, migrants admitted on a permanent basis under Canada’s skilled labor immigration program can sponsor the immigration of parents, grandparents, brothers or sisters, nephews or nieces, and granddaughters or grandsons who are orphaned, under eighteen years of age, and not married or in a common law relationship. A separate indicator measures the existence and scope of judicial remedies available to migrants to challenge the refusal by authorities to allow family formation/reunification.

The third indicator in this category assesses the limits, if any, on the spouse’s right to work in the host country without a work permit. The indicators allow for three possible scores. Programs in some countries, such as the United Kingdom, allow spouses full and immediate work rights without any restrictions.20 Others do not grant spouses without their own work permit the right to work in any job in the host country. The spouses of migrants admitted through the general labor scheme in the Netherlands, for instance, are not allowed to take up any employment unless they first apply for and obtain a work permit. An intermediate score is given for programs that grant spouses the right to freely accept employment in only some sectors and/or occupations, and/or are subject to quotas (as is the case under Austria’s Key Worker Migrant Program).

Methods, Data, and Limitations

Normalization and Aggregation Procedures

The computation of aggregate scores for the overall rights and openness indexes requires a procedure for combining the scores for the individual indicators. There are two key questions: How, if at all, should the indicators be normalized and weighed? How should the scores for each indicator be aggregated to generate the overall index? It is essential to emphasize the fundamental importance of these issues. Different procedures for normalizing, weighing, and aggregating indicators will obviously produce different overall indexes.

The rights and openness indexes developed in this analysis are based on equal weights and a simple aggregation procedure that involves adding up the normalized scores for each indicator to produce the overall indexes. The main arguments in favor of equal weights are transparency and simplicity. Any procedure that departs from equal weights needs to be based on convincing reasons explaining why and how some indicators matter more than others. In this analysis of openness and migrant rights, there is no set of weights that would be obviously superior to the default of equal weights. It is, of course, entirely possible that in practice some indicators are more important than others, in the sense of having a greater impact on what is being measured. For example, within the openness index, the presence of a hard and small quota can be expected to have a bigger impact on a country’s openness to labor immigration than the requirement to prove self-sufficiency. There is, however, no objective way of assessing this difference. Furthermore, since different countries may operate different modes of immigration control (i.e., employ different tools for restricting labor immigration), assigning a set of weights that differs from equal weights runs the risk of introducing various types of bias. A third argument against nonequal weights is that the relative impact of a given mechanism for restricting labor immigration could conceivably vary significantly across countries.

There are statistical tools, such as principal component analysis, for providing a purely mechanical solution to the problem of identifying suitable weights for the indicators. Principal component analysis is a data reduction procedure. It tries to identify the critical variables that account for most of the overall variation in the data. While useful for some purposes, the main problem with principal component analysis in the context of this chapter is that it is not based on any conceptual relevance of the indicators but instead simply on the degree of correlation between them. A further problem is that having eliminated some components, the remaining indicators after principal component analysis do not have straightforward interpretations as they are partly measuring effects of other indicators that have been excluded. For these reasons, principal component analysis is not an appropriate methodology for the construction of the rights and openness indexes. The construction of these indexes must be based on a conceptual framework and judgment of the substantive issues involved rather than purely on statistical correlations.

The procedure for normalizing and aggregating the individual scores adopted in the construction of the overall rights and openness indexes involves two steps. The first step is to normalize the scores for the individual indicators. For the sake of transparency and simplicity, I have adopted a common and simple procedure that normalizes the raw data, and ensures that all the scores for the individual indicators fall between 0 and 1:

Normalized score = (actual value – minimum value) / (maximum value – minimum value)

The second step is to simply add up the scores for the individual indicators to produce the overall rights and openness indexes and relevant subindexes. The score for the overall openness index thus ranges from 0 (closed) to 12 (completely open), and for the rights indicator from 0 (no rights) to 23 (full equality of rights). Whenever useful, these scores are again normalized to fall between 0 and 1.

Data Sources, Implementation, and Limitations

The indexes developed in this project are the first-ever measures of openness to labor immigration and migrant rights in a relatively large number of countries. A team of five researchers helped construct the indexes during March–August 2009, for the period early 2009, and to capture potential policy changes due to the economic downturn, also for early 2008. The scores are derived from a desk-based analysis of national immigration laws and regulations, labor law, and where relevant, constitutional laws. In a few exceptional cases, the scores to some indicators in some countries are based on relevant secondary literature and analysis.

The data collection and processing involved four stages. As a first step, the key labor immigration programs for each country were identified. Second, researchers spent an average of three days analyzing relevant legislation and policy documents, and suggested draft scores. As a third step, the scores were discussed and finalized for each country. Finally, the scores of each individual indicator were checked for consistency across all programs and countries.

The comparative measurement and analysis of migrant rights and immigration policy is still at a nascent stage, primarily because of the significant complexities and conceptual as well as methodological challenges involved. It is important to be clear and transparent about the limitations of the indexes analyzed below. Although every effort was made to score the indicators based on the best available information that could be accessed from Oxford University, the scores to the indicators undoubtedly include some degree of measurement error, and by the nature of the project, sometimes required a degree of judgment. In most but not all cases, researchers spoke the language of the country being analyzed. In some cases, such as Japan, Thailand, and some of the Gulf countries, the scores are based on English translations of the relevant laws and policies. The data obtained for some countries were better than for others. Countries for which data were considered too unreliable—including Egypt, India, Libya, Russia, and the Ukraine—were excluded from the analysis at this stage. Despite these caveats, the obtained scores are considered accurate and robust enough to provide the basis for an exploratory analysis of the relationship between openness, targeted skill levels, and migrant rights associated with different labor immigration programs. The scores may not be accurate for every single indicator for every program and every country in the sample, yet they do collectively provide us with reasonably robust measures. The indicators and scores used in this project are, I would argue, more reliable than some of the existing indicators, whose scores are based on subjective judgment by a small number of country experts.

There are also a number of conceptual limitations and assumptions, including generic issues that affect any index as well as particular questions that arise in the construction of policy and rights indexes. Can a policy really be quantified and measured by an index? Can the presence and scope of rights be reduced to a number? Most important, can we really compare and integrate measures of different types of rights that, some contend, are incommensurable? These are all legitimate questions. They do not invalidate the usefulness of the exercise, however; what they do suggest is that any results need to be carefully discussed and interpreted in light of the underlying assumptions and limitations.

The remainder of the chapter presents and examines some key results of the empirical analysis. Before looking at the evidence on the hypothesized relationships between migrants’ rights, skills, and openness to labor immigration, it is useful to highlight six key features of labor immigration policies in high- and middle-income countries. (Table A.2 in appendix 1 provides basic descriptives of the aggregate openness index, and table A.3 gives a detailed list of all 104 programs analyzed, together with their aggregate openness scores.)

First, the great majority of labor immigration programs included in this study (just under 90 percent) admit migrants on temporary rather than permanent residence and employment permits. Yet there are significant regional variations. Almost all the programs in Europe and Asia are TMPs (i.e., they do not grant permanent residence on admission). In contrast, TMPs constitute much lower shares among the programs in the traditional “settler countries and regions” including North America (just over half are TMPs), and Australia and New Zealand (less than half are TMPs). It is important to add that the share of TMPs in a particular country or region does not necessarily reflect the share of temporary migrant workers admitted, as the size of different programs may vary considerably. In recent years, many of the traditional settler countries, especially Canada and Australia, have moved toward policies that significantly increase the number of temporary migrant workers.

Second, as shown in figure 4.1, there is a crucial inverse relationship between temporary visas/work permits and the skill level targeted by the immigration program. All the programs for admitting low-skilled migrants are TMPs, with about two-thirds issuing strictly temporary permits that do not allow upgrading to permanent residence status. As we move up the skill ladder, the share of permanent immigration programs increases while that of strictly temporary programs declines. Nevertheless, even among programs targeting highly skilled migrants with second- or third-level degree, two-thirds are associated with temporary rather than permanent residence status on arrival.

Third, as shown in figure 4.2, with the exception of the self-sufficiency requirement (included in over two-thirds of the programs analyzed here), supply-side restrictions on labor immigration are much less common than demand-side restrictions and quotas. This is not surprising in light of the dominance of TMPs in the sample. Supply-side restrictions are most common among permanent immigration programs for skilled and high-skilled migrant workers, such as points-based systems in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The most common demand-side restrictions are the requirement of a job offer (over 90 percent of programs include this requirement), labor market tests (used in just over half of all programs), and restrictions on the conditions of employment of the migrants (used by almost 40 percent of programs). Of all the twelve openness indicators, restrictions by gender and marital status as well as through trade union involvement are the least commonly used tools of limiting labor immigration among the programs included in this analysis.

FIGURE 4.1. Temporary and permanent labor immigration programs by targeted skills, 2009 Notes: only LS: programs that target only low-skilled workers; LS: programs that target low-skilled workers and possibly others; MS: programs that target medium-skilled workers and possibly others; HS1: programs that target high-skilled workers and possibly others; HS2: programs that target very high-skilled workers and possibly others; onlyHS2: programs that target very high-skilled workers only.

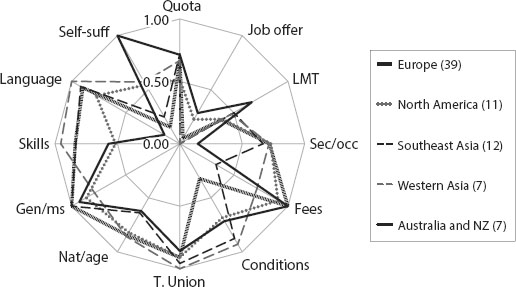

Figure 4.2 also shows that there are important regional variations in the types of restrictions used. Some of these differences are likely due to differences in welfare states, labor market regulations, and to some extent, political systems. For example, the requirement for migrants to prove self-sufficiency before admission is most common among programs in Europe (used by 85 percent of programs) where welfare states are larger than in other regions in the sample (the average for all programs is 70 percent). Similarly, restrictions on the migrants’ wages and other employment conditions are highest in Europe, and lowest in Southeast and especially western Asia. The western Asia sample includes Israel plus four GCC countries (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates) with highly segmented labor markets along with high degrees of inequality between citizens and noncitizens. A key tool for restricting labor immigration among Southeast Asian countries (used by two-thirds of programs) is economic fees, but this is much less so among programs in other regions (fewer than 10 percent of all programs in the sample use economic fees).

Fourth, although the correlations between individual openness indicators are mostly statistically insignificant, there are some types of restrictions that tend to be used as complements (i.e., in combination) while others appear to be substitutes (see table A.4 in appendix 1). For instance, labor immigration programs that require applicants to have job offers also tend to operate labor market tests (statistically significant correlation coefficient of 0.35 for all programs, and 0.40 for programs in upper-high-income countries only). Labor market tests are also positively correlated with the involvement of trade unions. There is a positive relationship between the requirement of a job offer and restrictions on the conditions of employment as well. These are expected results given that all four indicators (job offer, labor market test, restrictions of conditions of employment, and trade union involvement) reflect concerns about the responsiveness of labor immigration to shortages in the domestic labor market and the impacts of immigration on the employment opportunities of domestic workers.

FIGURE 4.2. Openness indicators by selected regions, 2009

Notes: All indicators range from 0 (most restricted; i.e., restriction applies—the center of the spider diagram above) to 1 (most open; i.e., restriction not used at all). The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of programs analyzed in the region. For an explanation of the openness indicators in this figure, see appendix 2.

Skills and language requirements tend to be used together. They are both inversely related to the requirements of having a job offer and the strength of the labor market test, suggesting that the two sets of restrictions, which reflect supply and demand factors respectively, are used as substitutes rather than in combination. Part of this negative correlation can again be explained by permanent immigration programs for skilled and highly skilled workers, which typically make heavy use of supply-side factors, but much less or no use of demand-side restrictions such as strict job offer requirements and labor market tests.

A fifth finding is that as a group, programs in countries in upper-high-income countries are less open to labor immigration than those in middle- and lower-high-income countries countries.21 Arguably, the greater attractiveness and higher shares of migrant workers in higher-income countries as well as their more extensive welfare states could explain this finding.

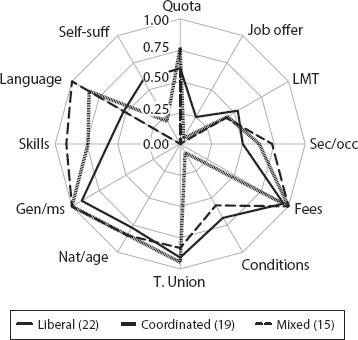

FIGURE 4.3. Restrictions by variety of capitalism, 2009

Notes: Classification (Hall and Soskice 2001): liberal market economies: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United States, and United Kingdom; coordinated market economies: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland; mixed market economies: France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. For an explanation of the openness indicators in this figure, see appendix 2.

A sixth feature of openness relates to differences in the modes of labor immigration restrictions by programs in liberal, coordinated, and mixed market economies, and liberal, social democratic, and conservative welfare states.22

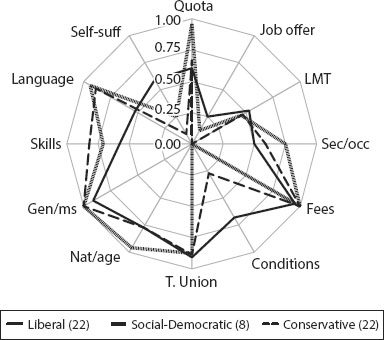

As explained in the notes to figures 4.3 and 4.4, the countries that Peter Hall and David Soskice (2001) characterize as liberal market economies are the same as those that Esping-Andersen (1999) classifies as liberal welfare states. Figures 4.3 and 4.4 show that compared to the programs in this liberal group of countries, programs in coordinated market economies (with social democratic or conservative welfare states) are more likely to limit immigration by requiring a job offer, self-sufficiency, and restrictions on the wages and employment conditions at which migrants must be employed in the host country. The latter is a direct result of being a more coordinated economy. In contrast, programs in liberal market economies and welfare states make greater use of specific skill and language requirements.23 These results partly reflect the fact that the liberal market economies and welfare states in this sample include three traditional settlement countries (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) that operate a significant number of permanent immigration programs.

FIGURE 4.4. Restrictions by welfare state regimes, 2009

Notes: Classification (Esping-Andersen 1999): liberal welfare states: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United States, and United Kingdom; Social democratic welfare states: Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden; conservative welfare states: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland. For an explanation of the openness indicators in this figure, see appendix 2.

Grouping restrictions by type (quotas, demand restrictions, and supply restrictions), programs in liberal economies and welfare states make less use of demand restrictions than those in coordinated economies. This is an expected result as public policies in liberal market economies are likely to be more employer led (or employer friendly) than in coordinated economies where governments, by definition, impose greater degrees of regulation on labor markets and are likely to be more concerned with the impact of immigration on the (larger) welfare state.

These results illustrate the different modes of labor immigration control across different types of market economies and welfare states. They do not suggest differences in the level of openness, though. In the sample analyzed here, there is no statistically significant difference between the openness of programs in liberal, coordinated, and mixed economies, or across different types of welfare states.

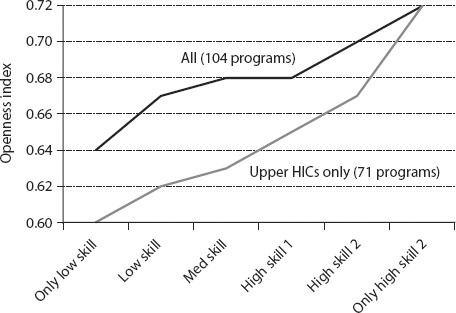

Openness and Skills

A seventh feature—which confirms the first of the three hypotheses outlined in chapter 3—is that openness to labor immigration is positively related to the skill level targeted by the immigration program. As shown in figure 4.5, programs that target high-skilled workers place fewer restrictions on admission than those targeting lower-skilled migrants. The differentiation of openness by skill level is most pronounced and statistically significant for programs in the highest-income countries in the sample (upper-high-income countries). A simple regression of openness on targeted skill level and income country group (distinguishing upper-high-income countries from other countries) confirms the significance of this relationship.24 Focusing the analysis on temporary migration programs does not substantively change the results.

FIGURE 4.5. Aggregate openness index by targeted skill level, 2009

Notes: Onlylowskill: programs targeting low-skilled migrants only; lowskill: programs targeting low-skilled migrants (and others); medskill: programs targeting medium-skilled migrants (and others); highskill1: programs targeting high-skilled migrants (and others); highskill2: programs targeting very high-skilled migrants (and others); onlyhighskill2: programs targeting very high-skilled migrants only; upperHICs: upper-high-income countries.

More detailed study of individual openness indicators suggests that the positive relationship between the overall openness index and the skills targeted by the immigration program is primarily driven by demand-side restrictions, especially the requirement of a job offer, strength of the labor market test, restrictiveness of quotas, trade union involvement, and in upper-high-income countries, restrictions on the occupation and/or sector of employment of the migrant in the host economy (see table A.5 in appendix 1). The lower the skill level targeted, the greater these demand-side restrictions on labor immigration.

In terms of supply-side restrictions, the picture is more mixed. Restrictions by nationality and age are significantly as well as negatively correlated with targeted skills. In contrast, the host country’s language and general skills requirements are higher among programs that target more highly skilled workers.

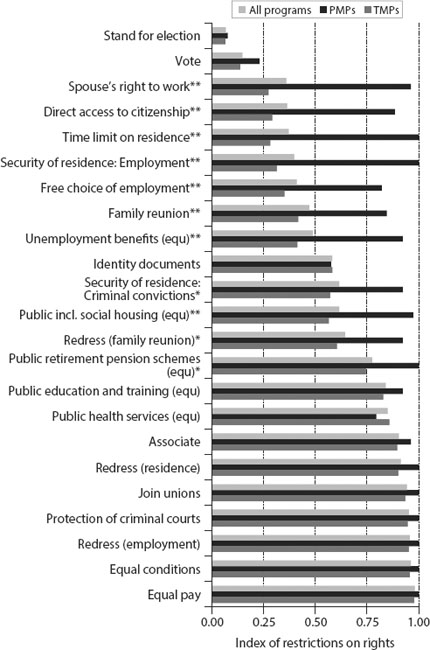

Migrant Rights

There is considerable variation in the rights granted to migrant workers under different labor immigration programs, both within and across countries. As shown in figure 4.6, restrictions vary significantly across different rights (the rights index ranges from 0 to 1, with a greater number indicating fewer restrictions on rights). Among the types of rights analyzed, the six most commonly restricted rights are the rights to stand for elections and vote (two political rights), the spouse’s right to work, direct access to citizenship, and time limit and security of residence (four residence and family rights). The two most restricted social rights relate to unemployment benefits and social housing. The right to free choice of employment is the only economic right that is commonly restricted. All other economic rights are granted in full under almost all programs analyzed. This is not a surprising result given that the labor laws and employment regulations in most (but not all) countries in the sample are generally applicable to all workers in the country and not just citizens.

A second key feature of migrant rights suggested by this analysis is that the rights granted to migrant workers under temporary migration programs are significantly more restricted than those granted under permanent migration programs. As shown in figure 4.6, however, there are important differences across different types of rights. Compared to permanent migration programs, TMPs place significantly more restrictions on most social rights (but not education and health), residence rights (not surprisingly), and family rights. Yet there are no statistically significant differences in terms of political and economic rights with the important exception of the right to free choice of employment, which on average is heavily restricted under TMPs, but rarely restricted under permanent programs.

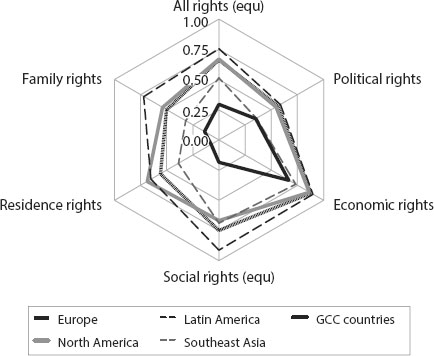

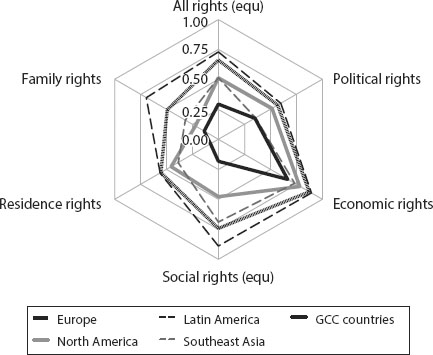

The rights that migrant workers enjoy under labor immigration programs also vary across different regions of the world. As shown in figures 4.7 and 4.8, this is true for the entire group of 104 programs analyzed here and TMPs only. For example, considering all programs, labor immigration programs in GCC countries and Southeast Asia place significantly more restrictions on migrant rights than programs in Latin America, Europe, and North America. Interestingly, this ranking of regions by restrictions on migrant rights is relatively consistent across different groups of rights, and it holds regardless of whether social rights are measured in relative or absolute terms.25 The only significant change when focusing on TMPs relates to North American programs, which impose an average level of rights restrictions that is closer to programs in Southeast Asia than in Europe.

FIGURE 4.6. Restrictions of migrant rights, 2009

Notes: PMPs: permanent migration programs (i.e., programs granting permanent residence rights on arrival); TMPs: temporary migration programs; the index ranges from 0 (most restrictive) to 1 (least restrictive); * statistically significant difference between restrictions on right under PMPs and TMPs (p < 0.1); ** p < 0.05; “(equ)” after a social right means that the score measures the degree of equality of rights rather than providing an absolute measure that takes account of whether citizens enjoy the right. For more explanation of each of the rights in this figure, see appendix 3.

FIGURE 4.7. Restrictions of migrant rights by geographic region, all programs (N = 104), 2009

Notes: The migrant rights scores range from 0 (most restrictive) to 1 (least restrictive).

FIGURE 4.8. Restrictions of migrant rights by geographic region, TMPs only (N = 91), 2009

Notes: The migrant rights scores range from 0 (most restrictive) to 1 (least restrictive).

Unlike openness to labor immigration, the overall rights index and most of the individual legal rights of migrant workers are not significantly different between programs in upper-high-income countries and other countries in the sample. Notable exceptions include the rights to family reunion, unemployment benefits, and health benefits, which are significantly more restricted under programs in upper-high-income countries.

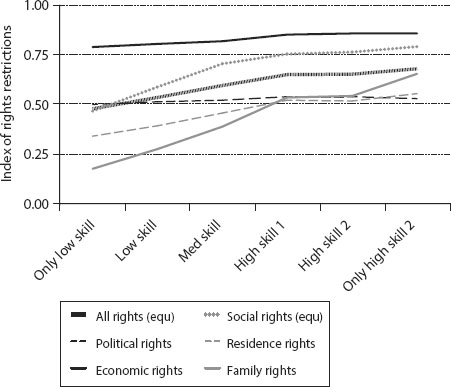

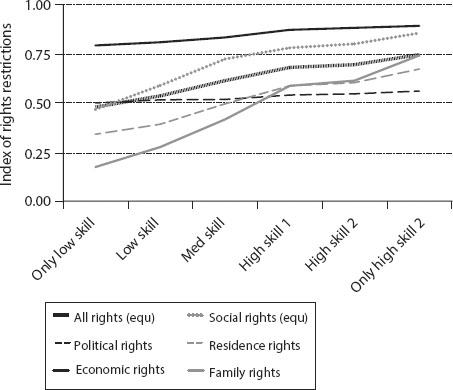

Migrant Rights and Skills

There is a statistically significant, positive, and consistent relationship between most of the migrant rights granted and the skills targeted by the labor immigration programs included in the sample. Programs that target more (less) high-skilled workers also grant migrants more (fewer) rights. Although this finding is not unexpected, the consistency of the differentiation of most types of migrant rights by skill level is striking. As shown in figure 4.9 (all programs) and figure 4.10 (TMPs only), most types of rights increase with targeted skills except for political rights, which do not vary across programs targeting different skills. Regression analysis also confirms the significant negative relationship between TMPs and rights as well as the importance of regional differences (see table A.6 in appendix 1).

FIGURE 4.9. Migrant rights and targeted skills, all programs, 2009

Notes: 0 = most restrictive; 1 = least restrictive (no restrictions).

FIGURE 4.10. Migrant rights and targeted skills, TMPs, 2009

Notes: 0 = most restrictive; 1 = least restrictive (no restrictions).

Focusing on individual rights, table A.7 in appendix 1 shows that about two-thirds of the twenty-three rights analyzed are significantly and negatively correlated with the skill level targeted by the immigration program. This includes most social, residence, and family rights along with the right to free choice of employment.

Migrant Rights and Openness