4453. “A Need for Gardens” (Richard Brautigan)

A poor humanist may possess his soul in patience … admit the

energy and brilliancy of the … physical sciences … and still have

a happy faith that … men will always require humane letters.

Matthew Arnold, “Literature and Science”

For as long as I have known her, my mother has liked to get very near the works of art that interest her. Once when I was a child, she brought me with her to see some paintings of animals—deer and dogs mostly, as I recall—and I watched her walk up so close to one painting that she could distinguish the individual hairs of its subject, hairs that seemed to have been painted one by one. I thought she was taking some kind of strange, scientific census, like differentiating the leaves of grass that make up a garden or a book of poems. And so she was. But that wasn’t all she was doing. Later (much later, I guess—maybe just now, as I started writing this), I figured out that she was up to something else as well. Now I think that all the counting was also her way of conjuring and continuing the animal life that the artist had set out for her to see, and her way of loving him for doing so.

I’m a little sorry it took me so long to get to all this. It’s a good thing that certain forms of animal life, like some species of gardens, can go on forever.

And if you really want to find them, you really always can.

Note: “My Grandfather was a minor Washington mystic” (Richard Brautigan, “Revenge of the Lawn”).

4454. “Love Enough to Be Kind”

the class of Grandes Amoureuses, of Women

Who Love Enough to Be Kind

Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse

—manage to love enough, or to love little enough to be kind? For a long time I used to be pretty sure it was the latter. For a long time, I used to think that the only love that could be really kind (putting someone else’s happiness ahead of its own hunger, rather than just pretending to) was something too feeble to care about getting some return (secret or spoken) for all its self-sacrifice. Then I began to wonder whether such not caring shows the strength at least as much as the weakness of the love that will so renounce its own strictly personal interest.

Now I wonder why I ever thought that the difference between such weakness and such strength mattered.

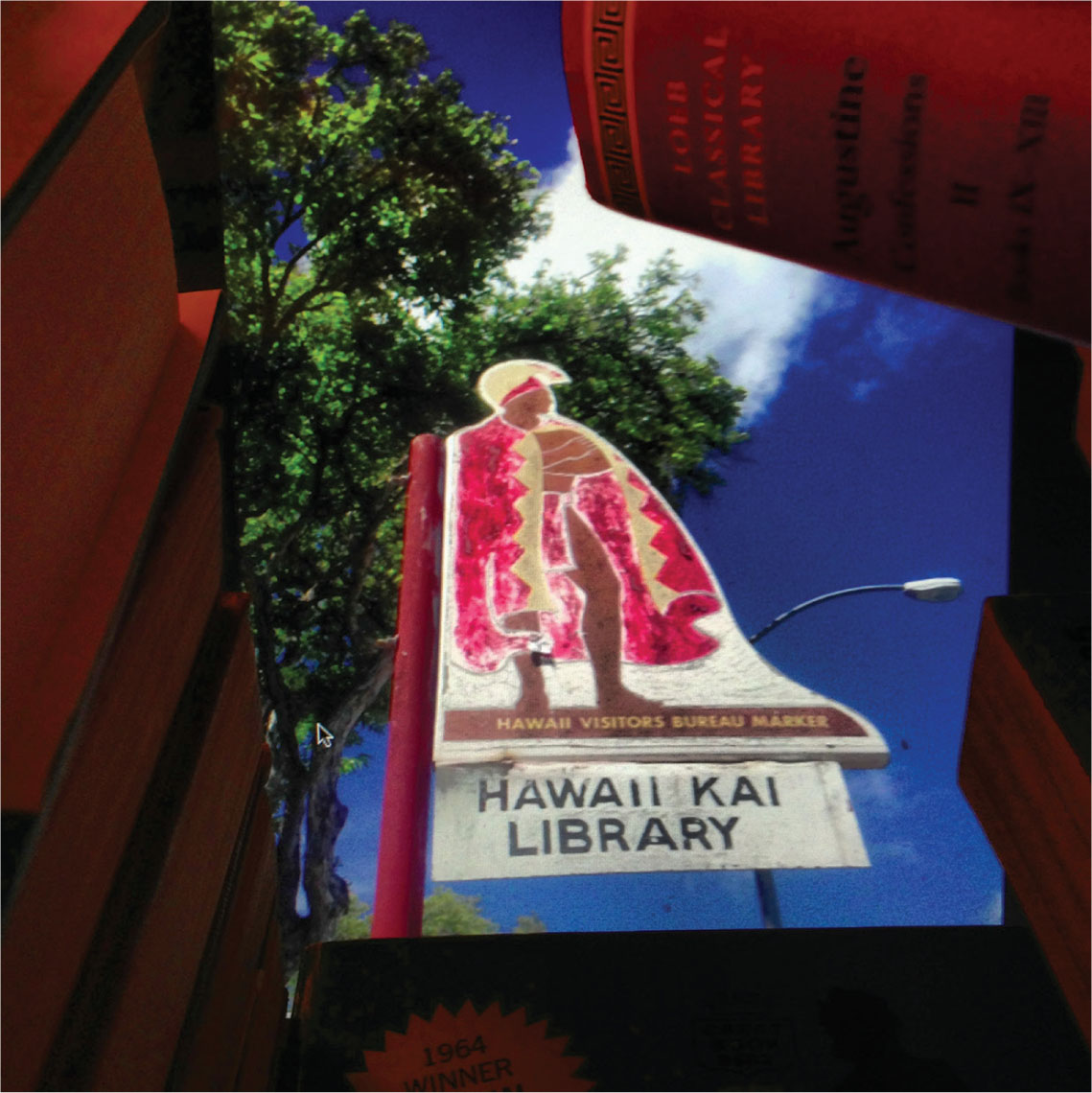

When I was in high school, I had a job at the local library, shelving books. After I went off to college, my mother, who took a hard job to pay for me to go, avoided that library. She kept expecting to see me emerge from the shelves, she told me, and it was more than she could take.

Don’t get me wrong. She didn’t stop reading. There are other libraries nearby. If she hadn’t kept reading, how would she be in a position, even now, to constantly correct me, often long-distance? (“You know history up to a point,” she’s fond of remarking.) Also, as hard as it is for me to really fathom, it turns out that her whole life doesn’t actually revolve around me.

Still, though, whenever I pass by that run-down old library, I can’t help but catch a glimpse of an eternal archive of the kind of love that will always live for others.

Note: “[She] lived for others” (Gary Wills on his mother).

4456. “without losing his reverence”

Let a man … learn to bear the disappearance of things

he was wont to reverence, without losing his reverence.

Emerson, “Montaigne; or, The Skeptic”

So much that seemed as solid as a rock just wears down or walks away forever. I always thought that I’d see you again, you say to someone who can’t hear you—someone you never see anymore.

But then, someone else comes along who will see you now, and hear you out.

Sometimes, the best of your love goes not to the person you meant to give it to, but to the one who sees how much you meant to give.

Note: “If my bark sink, ’tis to another se[e]” (William Ellery Channing, “A Poet’s Hope,” citation altered).

4457. “his sincerities are … elegiac”

His sincerities are quietly, almost passively elegiac.

Richard Poirier, The Comic Sense of Henry James

Personally, I’ve never met a sincere sentiment that didn’t have its root in ground that’s pretty much gone now—plowed over and under by some tract-developed cynicism. Just think how old-fashioned most every form of sincerity feel to us—like so many old-school forms of High Society, only something more like the opposite. Even those sincerities uttered by the most recent, thoughtful, individual child may mostly recall to us outmoded selves (ours or others), drowned out by the newer engines of conceit and convention, like the sound of a Grandfather’s Mythic Model A, by the speed-of-sound traffic of today’s superhighways.

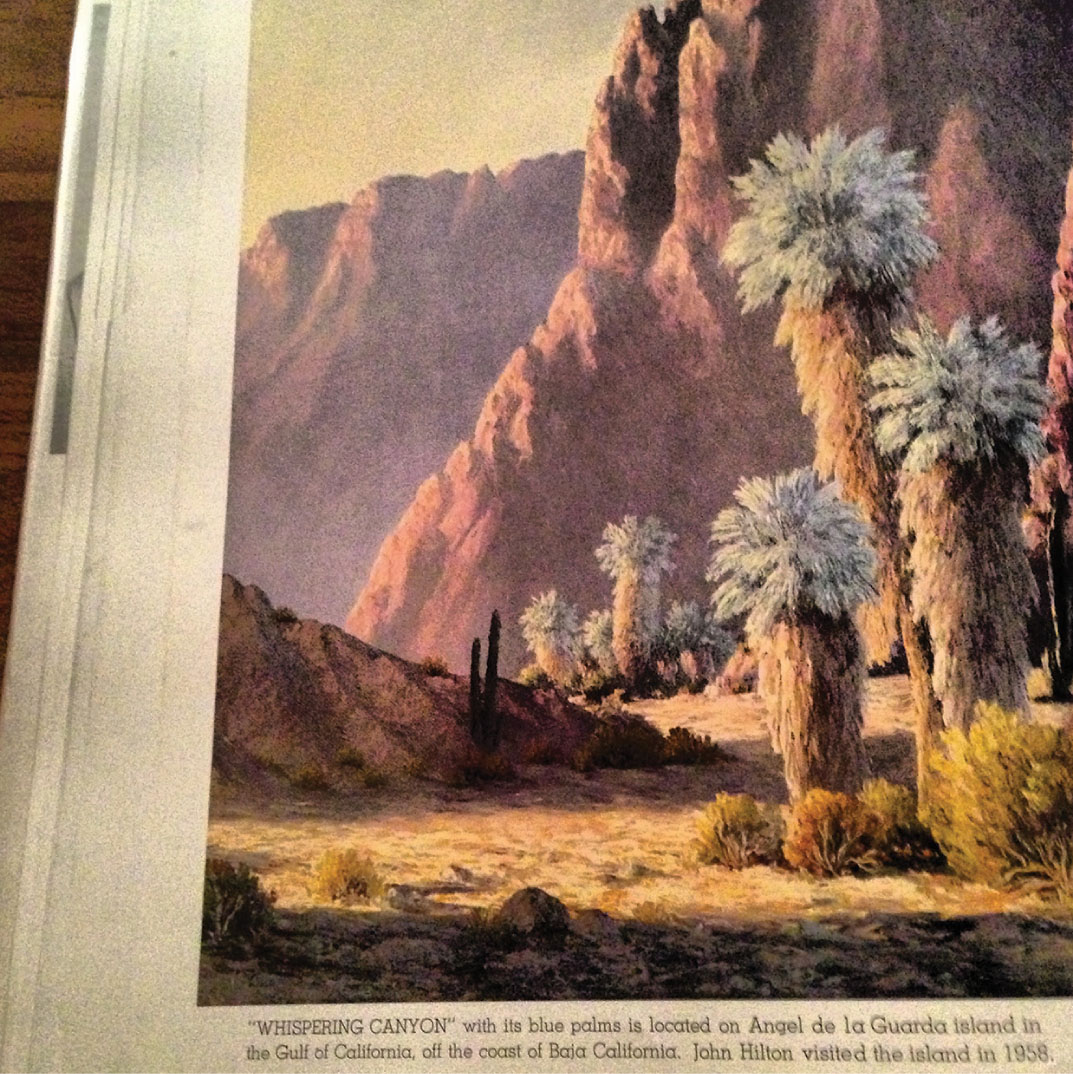

You can’t take a picture of this, a boy said to me this summer about the desert sunset of the Southwest, his voice made quiet by the sincere recognition of an evening light that could never be saved. You can’t take a picture of this, either: the look on his face as his eyes reckoned with a waning desert light he knew no picture could reproduce.

Still, sincerity itself, even at its most “passively elegiac,” even when it’s most realized, knowing that it can’t save what it wishes with its whole heart that it could, always lays its hearer open to something else: a rumor of a high-fidelity rendering or reprise of some frontier, some future or forgotten ground of openness, always out of reach, but never out of earshot, as near and far as the next true voice you might just hear (never quite here): Yonder, yes yonder, yonder, … (Hopkins, “The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo”).

Note: “What then is the aura? … the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be” (W. Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproducibility—Second Version”).

4458. “Make gentle the life of this world” (Aeschylus)

At present, I don’t mind confessing … (in strict confidence) that

I sometimes find it difficult to keep up a genteel appearance. I

have felt the cold here. I have felt something sharper than cold.

Dickens, Bleak House

Some nights you wonder what’s stronger: the something sharper than any cold that threatens to tear apart all your gentleness, or the someone sweeter in the air who coaxes you to feel confident enough to confess your fear of exposure to such a bleak risk.

And then, by the time you’re done choosing your confession, something wonderful has happened (Who knows how?) (G. M. Hopkins), but somehow you trust the world enough again to love it. You love the world enough again to trust it. Somehow by some unpredictable advance of keyboard and pen, the scales have turned toward gentleness.

Mirabile dictu: Sweetness Follows.

Note: “Live your life filled with joy and thunder” (R.E.M., “Sweetness Follows”).

4464. Two Cheers for Vagueness

led by dream and vague desire

Tennyson, “To the Master of Balliol”

If you were to ask me ten years ago what I really wanted and how I wanted it, I’d tell you quicker than a native speaker could say “Sea of Silver” in Spanish. But a lot can happen in ten years. A lot can get clearer and a lot less so. Now, ten years later, I clearly have no clear idea about what I want—only a few clues. One of those clues is that I’m not the only one who feels so confused. When it comes to what I want, I’m pretty sure that there are a lot of people I teach and a lot of people who teach me who are as much out to the foggy sea as I am. (And that sea used to shimmer so!)

Sometimes people are brought together by a common sense that they know what they want (from one another and beyond). Sometimes by a common sense that they don’t.

Maybe someday I’ll have a clearer feeling of direction. Maybe, someday, I’ll decide that all I really want comes down to some annual report of what I’ve actually done or vaguely dreamed of doing. I can live with that.

You want to know why I can live with that? I’ll tell you why I can live with that. Because I think you can live with that, too.

Note:

All I really really want our love to do

Is to bring out the best in me and in you too.

Joni Mitchell, “All I Want”

Every liberal-minded man must feel the shame of it.

This is the end. I am not going to keep a diary anymore.

W.N.P. Barbellion on the Treaty of

Versailles, in A Last Diary (1919)

But someone else will come along and keep it up, and we both know who that someone else will be. It will be you and I and a lot of people who come after us: that’s who it’ll be. We’re the ones drafted to keep that diary now, the ones determined to cross the gap that no one can cancel. (You know: the gap that spells the differences that divide the States of Men, and the endless destruction of the hope to end all the Wars between them.)

Anyway, ready or not, here we come: press play.

Note: “continuingly attentive to the relation of words and deeds, when they seem to become one another” (John Hollander, The Work of Poetry).

4466. “But in the movie, died”

… in the book he got the girl

But in the movie, died

John Updike, “In Memoriam”

It’s funny where the mind will wander: I wonder if he would have gotten the girl any way at all if he hadn’t perished some other way as well. Just think how many people you love had parts that got lost in the shuffle of a move (something shattered, splintered, something stolen away).

And just think how their loss only makes you love them all the more.

Note: “shade of someone lost” (Tennyson, In Memoriam).

personal correspondence

4468. “It’s the kingdom of heaven”

There always comes a moment when people give up struggling

and tearing each other apart, willing at last to like each

other for what they are. It’s the kingdom of heaven.

Camus, Notebooks

It’s like a great scene in some movie about accepting a mermaid, where Tom Hanks asks John Candy what he thinks about women running around naked through the streets of New York. I’m for it of course, Candy replies. Hard not to get happy after a line like that: hard to be hard on the dude who delivers himself of this sentiment: hard not to feel the line of the laugh extend to forgive the one who laughs as well as the one who is laughed at.

That’s terrible, my mother will say while she’s laughing her head off at some bawdy comedy.

It’s her way of telling that she’s as close as she’ll come to heaven on earth.

Note:

natural sinners put him at his ease,

And so he enters the cathedral door.

(Witter Bynner, “Santa Fe”)

4474. “the small band of true friends”

the small band of true friends …

the perfect happiness of the union

Jane Austen, Emma

My mother and I seldom speak of heaven. Neither of us imagine that we have any idea of what it would be like. Last night, though, in the middle of our usual conversation, the subject unexpectedly arose. I said that as far as I could tell, what people mostly mean by heaven is some place where they get to be with friends and family who are gone now: that for many people, it wasn’t so much a strict belief as a dim hope for such a get-together. This conjured an image in her mind of all of the dogs she’d ever had (she’s had a lot), starting when she was a little girl. As she began to name them (the list sounded a little like Santa’s Reindeer Roster, only a few of the names forgotten), her voice roved away from the voice that I know as her voice, as if it were following the band of dogs to some place far from here. “I think they would all get along,” she said, a little shyly.

How could I help but believe her?

Note: “Hatted, as for departure, away from us … sometimes talking, sometimes not, always in conversation” (Stanley Cavell, “Adam’s Rib,” Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage).

4477. “The end of art is peace”

The end of art is peace

Could be the motto of this frail device.

Seamus Heaney, “The Harvest Bow”

So true. It’s also the place where sickness and anger, and all their ugly memories, finally come to reach an understanding. (When you’re peaceful enough, what you’ll remember about your father are the good times: like when he tried his bashful best to show you how to use some tool for gardening or just getting along.)

Your father and his tools: here’s a Parable, a Paradox, from our own backyard: all those things that he tried to show you how to use (lawn mowers, long dividers, and the like)—they seem more useful now that they’ve been tossed from the tool-shed: just lying there, exposed to the elements, their edges worn away, his rusty implements reveal themselves, for what they really are at last, in the reflected light of his love.

Note: “swords into plowshares” (Isaiah 2:4).

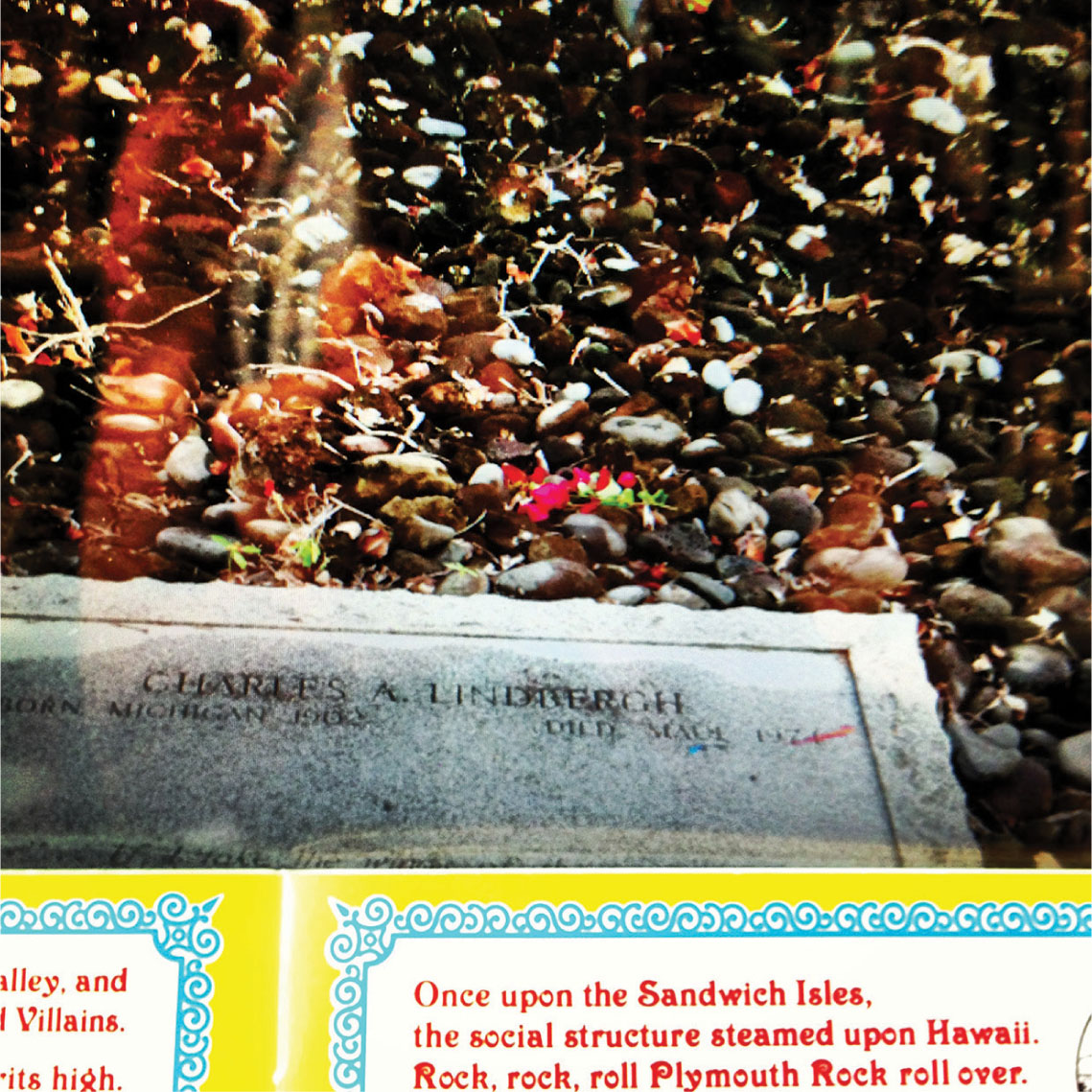

… our Puritan anxiety to “do ye next thing”

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Gift from the Sea

What’s next, you always worry. What do I have to do next, and if I don’t do it, what will be done to me? What have I already done to ruin everything—what have I done? what have I done?

Sometimes when the fear gets thick enough, life just feels like one long “to-do” list. You get going and pretty soon you’re running around in circles and you don’t know where to start or where to stop.

But wait: maybe the thing your worry really wants you to do right now is to quit doing things (fighting wars, flying planes, finding ways, etc.) for right now, and just spend a little quality time with it.

I mean, it’s like with any other good friend. You should enjoy him while you can. He always has a lot of good things to say if you just hear him out and sometimes read between his lines. He’s not just barking orders. He’s also bearing gifts. And it’s not like he can hang around forever—just until you’ve unwrapped the presents that he’s brought you from a long way overseas.

Note: “a spirit of courage, and wisdom and zeal” (Thomas Shepard Jr., “Eye Salve,” The Puritans in America: A Narrative Anthology, ed. Alan Heimert and Andrew Delbanco).