4047. “Several people on the trip told me that I was an inspiration, which made me feel good” (The Author’s Mother)

And now you will no longer wonder that the recollection

of this incident on the Acropolis should have troubled

me so often since I myself have grown old and stand

in need of forbearance and can travel no more.

Freud, “A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis”

Many years ago, in the middle of the hardest defeat of my life, my mother came to visit me in New York. My apartment there is small; I, especially in my compromised state, smaller still, and my powers to accommodate her sizable stock of certitudes and self-doubts—their aggregate volume sufficient to fill any proscenium worth its salt—powers of forbearance that hardly amount to the armor of Hercules even in the best of times, reduced to the tattered thinness of a single fig leaf. She couldn’t have come at a worse time, I thought—until I realized that she couldn’t have come at a better one.

Seeing that I was in no shape to chaperone her, she struck out on her own. (She is, after all, according to her own Ancient History, of “pioneer stock.”) One morning, she left before I was awake and called me later from the viewing platform at the top of what was then the City’s tallest building, while I was still in bed. From this height, she felt called upon to tell me something about herself that she instructed me not to repeat, and I will not disobey her.

What I can tell you is that what she conveyed to me when I was troubled, and in need of forbearance, was a memory of falling down and getting up again that dissipated the disturbance that left me thinking I could travel no more.

And now I no longer wonder that my sorrow at the thought of the day that she will pass beyond me is matched by the strength with which she has prepared me to meet it.

Note: “The two days in Athens were great but tiring. I actually made all of the excursions (one exception: a Venetian castle in Crete, but went everywhere else). Some people did not climb up the Acropolis, but I did. Why come to Greece and not go up? Was worth it. I was glad that I had both walking sticks. It really made it possible. Several people on the trip told me that I was an inspiration, which made me feel good. I will tell you all more about the trip later, and show you the pictures when I get them done” (extracted from my mother’s report on her most recent travels; her destination this time was the Mediterranean rather than Manhattan).

4050. “I think to myself: where have they gone?”

Alfred Kazin

Wait: They were just here—friends, neighbors, teammates, allies, opponents, friendly international competitors and collaborators (they’re friends, and they’re foes too—Joni Mitchell, “Trouble Child”)—all those sullen and sudden types who stood between you and the Bar, or raised it beyond, to all Recognition. All those crowded conversations (free or freighted), come crashing through the night and there you are (wait: I mean, there you were), suddenly discovering yet once more—one more round!—the engrossing problem of other minds. (You thought you’d be together for the length of a couple of drinks or all of your decades, but he or she or they, or the destiny enfolding each and every one of us, had other plans. Destiny stands by sarcastic with our dramatis personae folded in her hand [George Eliot].) Where are they now, all those wild things, all those quick, bright things? You knew even then, in the midst of the attracting, distracting swag and swagger, they’d all come to confusion, and you first of all.

Still, though, dizzy as I get just thinking about all those ridiculously dizzy raptures, now mostly faded into the light of common day—I just know, lonely as a cloud as I guess I like to be now, (Wordsworth), as high and dry as my Ice Age demands I be now (dryer, and way less dirty than any martini I ever saw back, as they say, in the day), still though, I’m pretty sure, still: I could drink a case of you and

Note:

Still I’d be on my feet

I would still be on my feet.

(Joni Mitchell, “A Case of You”)

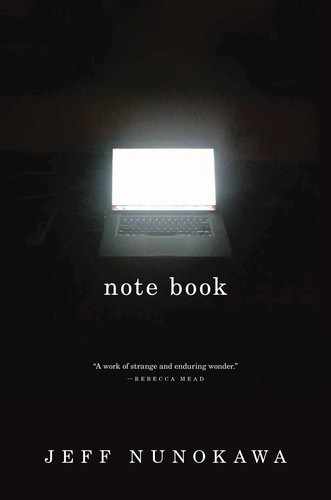

4060. Noncomputable Memories

Like countless others in the digital age, I seem

To have written a memoir on my new computer.

It had no memories—anyone’s would have done,

And mine, I hoped, were as good as anyone’s.

James Merrill, “Scrapping the Computer”

My mother is wary of these machines. She worries that they coax us to confess at least a little more than we normally would, and a little more than we ever should—like a crafty analyst or crafted analog, or one of those calculating characters from weird novels or nights, who get more tears out of and in you than you ever intended for them to get. I know she’s right (she pretty much always is), but here’s the thing: if, as I hope, my memories are as good as anyone else’s, I’m also fairly sure that they’re no worse than anyone else’s, either. And even in the worst-case scenarios (all those ancient and modern histories of anguish, too dark to describe in detail or heal in whole), you try to keep on course, and patch together something better out of something seriously bad—like when Hepburn cheers Bogart on as he hauls their failing craft (The African Queen) through the last swamp, quietly knowing quite well that they’re quite doomed, and quietly knowing that he quite knows it too.

Note: “Perfectibility and the associated idea of equality … he was keen to reaffirm” (Etienne Hofmann, “The Theory of the Perfectibility of the Human Race,” The Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Constant).

4063. “Things answer only if they are questioned”

Things answer only if they are questioned, and … we cannot

overlook the fact that in their emergence … answers are

systematically conditioned … through their bond to the question.

Erwin Straus, Event and Experience

Except, it seems, when you’re dreaming, and then everything (you included) appears to be nothing but answers, no questions asked. And the answers (mutatis mutandis) always more or less amount to the same one: Yes, I miss you more than I can bear.

What a relief, when we rouse ourselves and get ourselves together and shake ourselves apart, and, settling down to “[our] books or [our] business” (Thackeray), start to see that

Note: “the thing we freely fórfeit is kept with fonder a care” (Hopkins, “The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo”).