5042. Waiting for Light

In a place of blackness,

Here I stay and wait.

Stephen Crane, “The Black Riders and Other Lines”

When it’s dark around you, shouldn’t you get up and go where it’s light? Isn’t that always the right thing to do?

Sometimes, though, if you wait in the dark for a while, the light will eventually come to you.

Note: “Patience” (Milton, on his blindness).

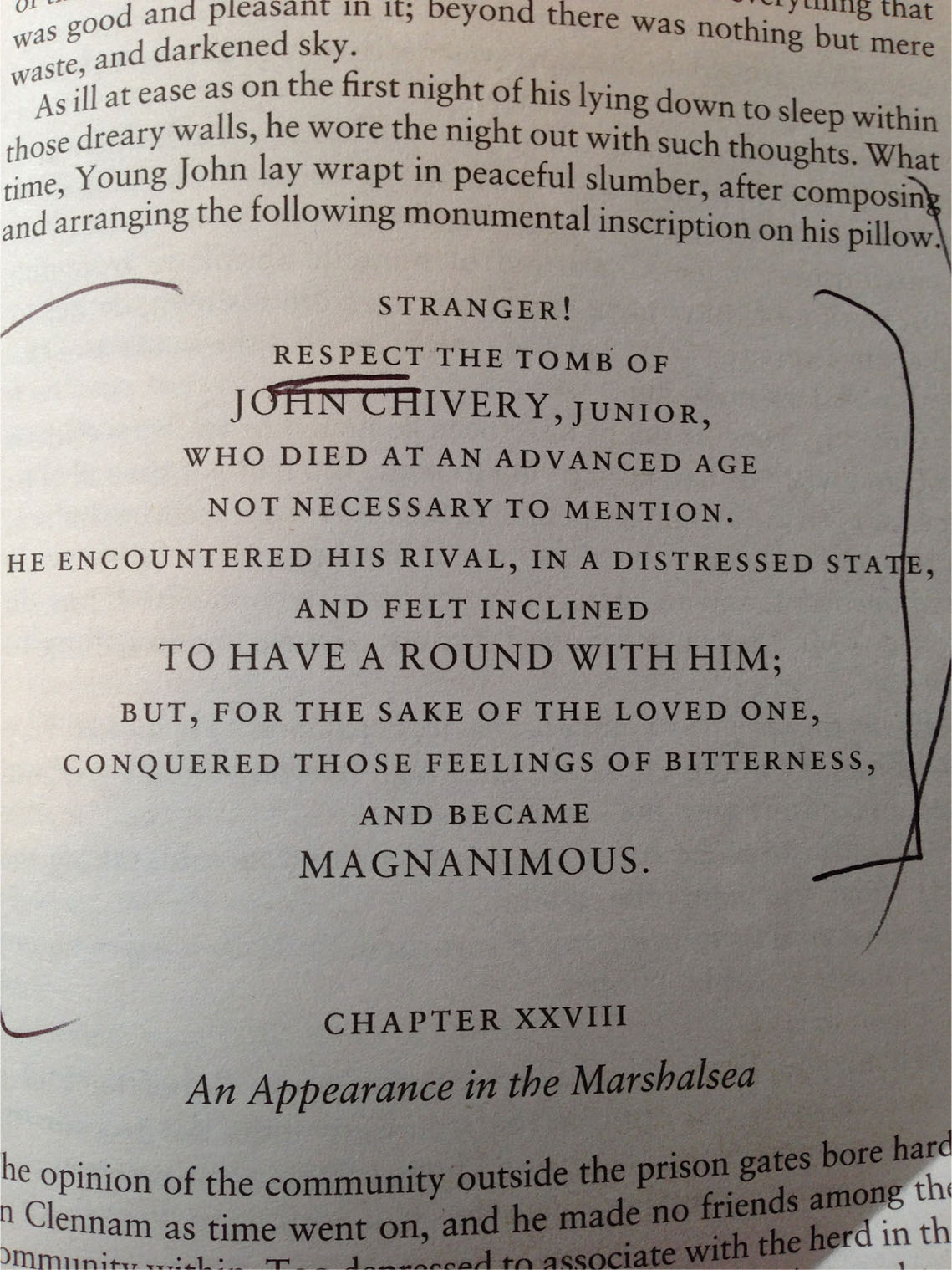

5043. Playing Fair with Your Feelings

Young John lay wrapt in peaceful slumber, after composing and

arranging the following monumental inscription on his pillow.

Dickens, Little Dorrit

You can read the inscription in a second. (I’ve laid it out below.) You’ve probably already produced some version of it yourself: It’s the script that we write in our heads where we re-cast our own personal, passing hurt into a drama fit for the Ages. Most of those scripts are so over the top that we take one glance at them and toss them on the reject-pile. There’s that ridiculous story, for example, of some bruised loser-dude who thinks he’s been crowned the King of Pain just because some pretty girl has said no to him and yes to someone else.

But you shouldn’t throw those scripts out without a fair reading. (Think of it this way: Just because you can see right through someone doesn’t always mean you should.) Most of the time, of course, taking your own feelings too seriously means that you’re not taking other people’s feelings seriously enough. On the other hand, casting yourself as the king of pain every once in a while can prompt you to act a little like a prince to other men.

Note: “for the sake of the loved” (Little Dorrit).

5044. “(I too in this dictum)”

If only one person were capable of leaving off one

word before the truth! Everyone (I too in this

dictum) overruns truth by hundreds of words.

Kafka, “Fragments from Note-Books and Loose Pages,”

Wedding Preparations in the Country

Truer words were never spoken, and I think I know why. I think we all do, actually, though it’s one of the few things we don’t like to talk about too much.

Of course we talk too much (certainly past Truth’s Finish Line). We need our words to keep ourselves together. How could we weave our dumb drive to be together, without our words? (It would be like running without socks, or on a wounded Achilles: neither ever a good idea.)

No wonder my mother repeats herself so much. “Oh, I know I repeat myself, but I figure if I tell the same thing two or three times to the same person, I’ve doubled or tripled the number of my friends.” Two or three times? Try twenty or thirty thousand times!—wait: have I already told you she said that? What can I say? I guess the best defense against the prospect of no friends is a strong offense (I too in this repeated dictation).

I mean, what’s the truth if not the end of all that we’ve got going on together here? (Maybe there’s more to it than that. I sure hope so: but it’s like what the Philosopher says: that about which we cannot speak, we must pass over in silence. He’s says it in German, and I’ve yet to see a translation that’s not awkward to enunciate. That’s why you say it over and over again. You keep thinking: this time, it’ll come out right. It’s like the great line—the greatest—from the New Testament: For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required. Try saying that ten times. I mean it: Try it.)

Anyway, like I was saying: before the Door of the Truth, what would the last word be except, except […], and let me tell you something, I have no intention of saying that word—not without a fight, anyway. It makes me think of a girl I knew in graduate school who decided she hated my guts and was all set to dissolve our friendship, but then thought about all the conversations she’d have to have with me about her decision: “All those lunches! All that processing! All those talks to get to the bottom of the problem!” (She decided in the end that ending it just wasn’t worth the trouble. Wise woman. Good choice. Good choice.)

Funny story, right? I can be a very determined person. Speaking of determination, my brother and I were talking on the phone last night, congratulating ourselves about how right and determined we are, unlike kids these days. (You’d think we were the ones who had grown up during the Depression, rather than our parents. It’s like what a friend said to me the other night: “We didn’t grow up during the Depression. We just grew up depressed”).

I’ve told you about my brother, haven’t I? He’s super straight (Old-School Straight), but not exactly the silent type. He talks as much as I do. Well, almost as much, anyway. Garrulousness and thinking we’re always right aren’t the only things we share, incidentally. Sometimes we also watch soccer on TV together. (It’s true, we watch for different reasons, but the important thing is that we’re together, right?) Anyway, I was talking to my brother on the phone tonight—by the way, speaking of brothers and stories, have you heard the one about the poet whose brother dies and he (the surviving brother, I mean) has to run halfway around the world to visit the grave? Actually, that’s pretty much the whole story—not much of a story, come to think of it. There’s not a lot more to say. Well, there one more thing to say, but I’m not saying it. Let someone else talk, for a change. It’s like what Erving Goffman (greatest sociologist ever—he’s all over the weird ways that people go along to get along) supposedly said at his wife’s funeral: today someone else will have to take the notes.

In any case, like I say, I’m not saying it.

Note: in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale (Catullus, 101).

5045. Coming and Going

How banal

Our lives would be, how shrunken, but for you.

James Merrill, The Changing Light at Sandover

With you around, there’s always so much to do: all that getting ready to say good-bye.

All that getting ready to say hello.

Note: Aloha.

5047. Another Country

I drew a map of Canada

Oh Canada.

Joni Mitchell, “A Case of You”

I shan’t have lied (Elizabeth Bishop, “One Art”): losing you was such a disaster that sometimes it’s easier to forget that you still exist. But I don’t forget for long. And as soon as I do, you all come back to me: like your waking after a winter’s worth of sleep, your smile after the snow has mostly melted, your speaking the funny way you spoke.

It’s evident (Bishop, “One Art”), what the Gospel sort of says: he who would gain his past shall first lose it.

Note: Je me souviens (official motto of Quebec).

5048. “hope”

His unbelievable verdict is this hideous and upsetting

world where even the moles dare to hope.

Camus, “Appendix: Franz Kafka,” The Myth of Sisyphus

Sometimes I feel like I’m just crawling along, fearful of something I can’t see.

Right about then, I lose sight of all hope.

Now I wonder: are these forms of blindness brother and sister?

You see, it’s not so much that I can’t see any hope: it’s more like I can’t see much of anything to hope for. Those look different, don’t they? One looks a lot like the end of a road, the other more like an open one.

People of our stripe have what sure looks like an infinite power to fear what we can’t see. Maybe we have an infinite power to hope for what we can’t see, too.

I hope so.

Note:

James Keller: Miss Sullivan? I’m James Keller.

Annie Sullivan: James? I had a brother Jimmy. Are you Helen’s?

(W. Gibson, The Miracle Worker)

5049. “sure as tomorrow morning”

sure as tomorrow morning,

Amongst come-back-again things, things with a revival

Hopkins, “St. Winfred’s Well”

Like the help that will heal the heart when it hurts: like the lightening that lightens before the light’s letting in: like the Send of the sweetness that settles the sentence: you’re like, all that, somehow.

Note: “(who knows how)” (Hopkins, “Pied Beauty”).

5050. “a perfect edition of my works”

I must make a perfect edition of my works, and

then I shall have nothing to do but to die.

Alexander Pope, “Conversations with

Jonathan—I mean, Joseph Spence”

I think I’ll take a pass on this one. For one thing, I don’t want to die yet. And for another, I haven’t finished my works or my work and have no plans to retire anytime soon. How could I, what with all the new jobs coming in? Why, just this morning, a new assignment came down the pike—one of those should you choose to accept it deals. Did you know that at least according to one report, there are nonviolent bees in the Himalayas? (“I could not determine whether it was stingless, or just well behaved.” – The Asian Journals of Thomas Merton.) Who would’ve guessed? Anyway, wouldn’t it be great to be so mild, either through the offices of Nature or Culture?

I don’t expect to lose my sting, but I’d sure like to learn how to soften its damage.

That shouldn’t take too long: no longer than the rest of my life.

Note: “O grant me, thus to live, and thus to die!” (Pope, aka The Wasp of Twickenham, Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot).

who would lose,

Though full of pain, this intellectual being,

Those thoughts that wander through eternity.

Milton, Paradise Lost

I wonder why he says Those thoughts, rather than these thoughts?—the painful thoughts that awaken you in the night and feel like they’ll stay forever.

Actually, though, they don’t stay forever. They leave in the morning—or the morning after that—or, well, some morning after that. One way or another, they’ll leave your allotted part of this intellectual being—just like everything else that dwells at the heart of the way we live here and now. (We were warned: don’t get too used to anything, they told us. All that we think dear [dark or light] will pass out of our hands, someday. No thought we call our own really is: such properties prove themselves so many pilgrims, bound to wander toward a promised land beyond our own little plots, our own little sway.)

These thoughts—those thoughts: look! (Elizabeth Bishop, “One Art”): it’s morning. They’re already wandering away.

Note: “Wayfarers All” (Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows).

There is no collapse of the will in Proust.

Samuel Beckett, Proust

Good to know, right? Talk about the opposite of helpful. At least so it seems that way at first (or at last). I mean, don’t must of us feel our will collapsing and corroding at least a little every day?

It reminds me of what a friend said when we were driving through a blinding blizzard north of Montreal one terrible winter night, listening to Barry Manilow report to us on the radio how he’d made it through the rain.

“It doesn’t do the rest of us much good,” my friend observed.

On second thought, though, maybe the proud prospect of Proust’s indefatigable will offers more roadside assistance to the rest of us than the simple news of someone else’s triumph in the midst of our own turmoil. He got tired a lot, I understand, especially as he got older. We can all relate to that (especially after a night without sleep), so let’s just start there. It’s hard to be tired a lot, and scary. How can I possibly do what I know I have to do when I’m this tired? Sometimes you get so damn run down, you wonder how you’re going to get to the end of the sentence or the session or the season you’re slated to finish.

But you do.

Note: “I can’t go on, I’ll go on” (Beckett, Standard).

method … in the service of the self

Maurice Natanson, Edmund Husserl:

Philosopher of Infinite Tasks

You’re a creature of habit now. (Maybe you always were—“you’ve always been compulsive,” my mother says—but you notice it a lot more now that you’re alone so much with your daily routines.) You wake up first thing in the morning and make your bed. After that you—well, you fill in the rest.

On your good days, the track of your rituals leads to a weird little romance. Somewhere along its way, your method meets up with your madness, and each brings out the other one’s personal best, the way that happy couples do. (You’ve seen it before.)

Your methods make your madness feel (for all its fear and trembling) a little at home in the world, like someone from a foreign country whose host teaches him enough of the language spoken there to get around.

Your madness, for its part, gives your method a little purpose in life.

And you know that the purpose is bigger than you.

Note: “Man … reveals and determines his situation by transcending it in order to objectify himself—by work, action, or gesture” (Sartre, “The Progressive-Regressive Method,” Search for a Method).

5056. “pathless ways into happy ones”

The first aim … is to show evidence of … perfect liberty

… converting pathless ways into happy ones.

Ruskin on the landscape of Dante’s

Paradise, Modern Painters, 3: xiii

On my first visit to his favorite foreign city, my best friend told me that to get to know a strange place, it was good to get lost a little there. Well, I got lost but good.

I got lost a lot that summer: It was the last time I got so lost.

It was the last time I fell in love.

Note: “unfettered and alive” (Joni Mitchell).

5057. Voir Dire

He went on lying and telling stories until he became

one of the world’s great masters of the art, and created

those grand imaginative lies which in our perplexed

condition somehow approximate the truth.

Steven Marcus, “Who Is Fagin?”,

Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey

I don’t worry about Dickens being hauled up on charges of Lying. Dickens knew his way around a courtroom, and he’d probably do a pretty good job representing himself (no fool, this Client). My guess is that he’d call only one witness—an expert character witness. Not that he’d listen to me, but I can tell you whom I’d have him bring in to testify. He’s German and he’s sort of dead and completely incompetent by now, but there would be no problem prepping his testimony: Whosoever built a new Heaven has found the strength for it only in his own Hell (Nietzsche).

“All those stories you told about people being better off and better than they could ever possibly be: how can you live with yourself?” the Prosecutor would ask.

Dickens would tell him off, big time: “Are you kidding? I only wish I could have told them taller!” he’d say.

He’d probably get off with Life.

And the Life that he’d save would be ours.

Note: “Tiny Tim, who did not die” (Dickens, “A Christmas Carol”).