CHAPTER 3

People

Leading in a Diverse World

Variety is the spice of life.

—William Cowper

One of the striking facets of modern business is the incredible diversity of the people—customers, colleagues, suppliers, and competitors—with whom we now interact. On a day-to-day basis, businesspeople engage people of every race, religion, color, creed, and personal preference—and while this variety can prove difficult to navigate, it’s also equipping young leaders to operate with agility, humility, and individuality.

Businesspeople, of course, have always had to lead diverse groups. Historically great cities like Piraeus, Alexandria, and New York were both cultural and commercial centers—where trade brought together people of every race, religion, and ethnicity. The private sector has often flattened class differences and offered excluded peoples a means of participating more fully in society. And, particularly in modern times, the entrepreneurial desire to reach every untapped (and profitable) niche has led to an explosion of various “long-tail” business ventures—from independently produced online music albums to art house movies and organic vegan restaurants.

And despite occasional resistance, workplaces around the world are becoming ever more diverse. On a global level, we may be living in one of the most inclusive times in history. As labor force participation increases and old racial, class, religious, and gender-based barriers are gradually lowered in many regions, the workplace is benefiting from a multiplicity of perspectives. In practical terms, these varied points of view are often quite necessary to reach the equally diverse array of consumers who now purchase goods from multinational institutions. Companies like Coca-Cola must now serve customers of every conceivable nationality, class, and creed. And they have often recognized the importance of this diversity more quickly than global political institutions.

That’s not to say these companies are perfect—far from it. Senior executive suites are almost all still dominated by historically powerful groups. In the United States, this means that many CEOs are older white males. In Mexico, it means that very few native people hold executive positions, and in many companies around the world it means an underrepresentation of women.

But the trends—at least on these conventional measures of diversity—are improving. In 1975, for instance, only 11 percent of the MBA class at HBS were women, 6 percent were U.S. minorities, and 15 percent were international. By 1995, women comprised 28 percent of the class, U.S. minorities 14 percent, and international students 23 percent.1 And for the HBS class of 2012, the figures had climbed to 36 percent women, 23 percent U.S. minorities, and 34 percent international students.2 Other business schools, like France’s INSEAD, are even more diverse (at least by country of origin), with INSEAD boasting a 2010 class that was 92 percent international, with 59 percent of students from outside of Western Europe, and 33 percent women.3 Those of us who recently attended business school can attest to the dedicated efforts these schools make to celebrate the religions, cultures, and passions of these various constituencies in very authentic ways.

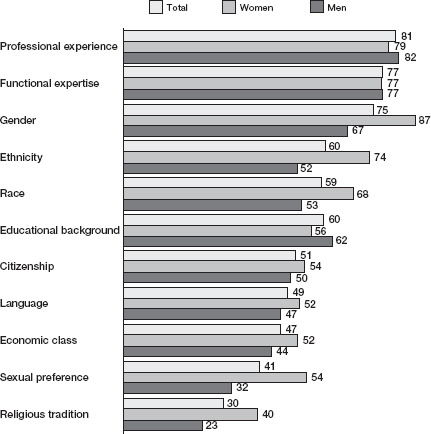

In our own survey, more than 92 percent of respondents answered “agree” or “strongly agree” to the statement, “Increased workplace diversity can lead to better business outcomes.” And a majority of respondents selected numerous categories when prompted with this statement: “I hope my future employers seek to actively foster the following elements of diversity in the workplace” (see figure 3-1)

FIGURE 3-1

Traits to foster in the workplace (percent responding “yes”)

Of particular interest is that these respondents don’t simply or even predominantly value racial, ethnic, and gender diversity—but diverse professional experience, functional expertise, and educational background. There seems to be a realization that out of these diverse experiences and identities come the strength of alternative perspectives—and next-generation leaders value those perspectives for the personal growth and professional success they can bring. This kind of diversity is both a challenge and an opportunity.

How Can We Lead in a Diverse World?

So where do we go from here? Certainly, the next generation of business leaders will continue to seek out inclusive workplaces; and they’ll likely be more effective at creating them because they themselves are more diverse in almost every conventional sense. But there is a growing belief that these external measures of diversity—particularly race and gender—are insufficient, and that sensitivity training programs are quickly becoming outdated and ineffective. We are also realizing that as important as the diversity of the people you lead is the diversity of your own leadership experiences.

This generation—fed on the aforementioned “long-tail” idea that each person is unique beyond his or her class, race, or gender, having unique tastes and preferences—is instead pushing for greater “wholeness” in the workplace. Alternative work schedules. Part-time or remote employment for mothers and fathers who choose to stay at home with children. Increasing incorporation of various religious and cultural practices in the workplace and increasing openness among employees about sensitive topics. This generation is pushing the idea that no one achieves happiness by cleaving herself in half—one part “professional” and one part “personal.” And as technological and cultural shifts increasingly allow such radically individualized diversity, the next generation’s leaders will use these shifts to gain a competitive advantage among customers even as they create a fuller work experience for employees.

This shift is perhaps most pronounced among millennial women. According to a recent Accenture survey, 94 percent of millennial women believe they can achieve “work-life balance”—a modern euphemism for happiness and fulfillment in one’s personal and professional life. And 70 percent list “maintains work/life balance” as a critical quality of a successful female leader.4

But the shift toward individualization is also clear, more anecdotally, in the changes companies are making to accommodate the needs of their increasingly varied workforces. Google has traditionally offered employees “20 Percent Time”—one day per week dedicated to their own pursuits and initiatives; 3M has promoted something similar with its “15% culture.”5 And in 2007 at least, Netflix claimed that it did not even track the hours of its employees.6 Far from the purview of radical companies in Silicon Valley, similar techniques are employed by the likes of JetBlue, which pioneered a program of at-home call center agents, many of whom were stay-at-home moms, in locations like Salt Lake City.7

Some pioneering companies are even embracing religion. Tyson Foods, for instance, created a chaplaincy program—staffing its various facilities with religious mentors who reflect the dominant faiths of workers in their particular regions, and are available to employees of all faiths for counsel. This program would seem eccentric if similar versions hadn’t been implemented, in whole or in part, in other prominent companies, such as Coca-Cola, R. J. Reynolds, and Texas Instruments.8

And, of course, businesses have often been harbingers of social change on lifestyle issues like sexual preference—many private firms began to offer same-sex partner benefits, for instance, long before same-sex partnership became a prominent political issue. According to the Human Rights Campaign, by 2003, 64 percent of the Fortune 100 offered same-sex partner benefits, and by 2009, that number had reached 83 percent.9

In short, companies are both expanding what it means to be “diverse” and doing so in ways that attempt to empower employees and offer them greater fulfillment, wholeness, and happiness in the workplace. And the next generation of business leaders is thinking in ever more innovative ways about how to expand these initiatives and lead these varied individuals in the pursuit of common goals.

The following stories address the idea of leading in a diverse world with the benefit of diverse leadership experiences. People are freer to live with greater passion and purpose when they feel more “whole” at work. Over the next twenty years, the best organizations will find ways to harness this incredibly diverse and dynamic talent pool to revolutionize the way they do business.

Nonconforming Culture

How to Feel Comfortable in Who You Are No Matter Where You Are

After five years in the consulting practice, KIMBERLY CARTER now works as a senior manager in the Leadership Development Group focused on talent development and corporate university launch for Deloitte. Kimberly earned a BS in accounting from Florida A&M University and a minor in German from Florida State University. She is passionate about education and leadership development.

Imagine walking through the streets of a small town and always being met with stares—most are inquisitive while others are laced with malice. Imagine questioning how someone could seemingly judge your worth or meaning without knowing anything about you. I experienced something like this when I lived in Germany as an exchange student in the early 1990s, a time of heightened hostility toward outsiders. At the time, Germany had an influx of immigrants following the collapse of the Berlin Wall along with a rash of fire bombings and “Ausländer raus” (“foreigners get out”) demonstrations that expressed a widespread negative sentiment. There were also a number of marches organized to address tolerance and to counter xenophobia. On the surface, many assumed I was an African seeking asylum and employment rather than an African American studying the language and culture. The internal conflict I felt from not always feeling welcome given the color of my skin spurred me to write a poem entitled “Identity” for my high school literary magazine. That experience not only exposed me to the stark realities of modern-day bias but drove me to never let others’ perceptions of me limit or determine my path.

Growing up in Mississippi, I was no stranger to prejudice. The impact of discrimination in the United States lingered past the abolition of slavery because certain laws prevented blacks from having the same civil rights (e.g., to vote, to use common restrooms or drinking fountains) as whites until the late 1960s, particularly in some Southern states. My parents experienced segregation firsthand and dealt with systematic injustice; however, those experiences fueled their desire to earn university degrees to create a better life and demand fair treatment professionally. Even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, some mind-sets had not changed enough to grant African Americans immediate access to education, jobs, and housing—even if they were overqualified. My family emphasized that education held the keys to equal opportunity. They grounded my life in the idea that you can excel in spite of adversities and still be true to yourself. With a deep appreciation for the faith and sacrifices of those before me, I kept those memories dear as I worked my way up in the business world. Although I initially struggled with the expectations to conform to corporate environments in order to succeed professionally, I soon discovered there should be no real boundaries for diversity in the workplace.

Many of those unspoken expectations and my feelings about them may seem superficial (e.g., always having straightened hair because natural hair is not acceptable, or feeling as if I had to represent the universe of African American females at work since we represented 1 percent of our starting class). But at the end of the day, I had to be comfortable with the person I saw in the mirror and happy with the choices I made. I recognized that companies figured out that the true value for them did not lie in having everyone look and act the same.

Over time, I’ve come to understand the profound impact of my experiences in Germany, growing up in Mississippi, and traversing the professional world, and translated it into three key principles in my life and career—three things I wish I could have told myself earlier as a young person entering the working world:

- Do not be afraid of what you do not know. Every day, I had to mentally prepare for any number of reactions from others, but that did not keep me from walking out the door and enjoying what Germany had to offer. Furthermore, I had the courage to make bold moves on my own and not let fear hold me back. For example, the decision to move from the South to New York and work in investment banking after college was considered a big risk. I dared to be the first in my circle of friends and family to embark out of state to work without any nearby support. My great-grandparents long ago made the decision not to migrate the family up North for industrial jobs in the early 1900s and took pride in establishing themselves as pillars in the local community (through teaching and preaching), yet I decided to seemingly break away from my Southern roots. There was an inherent fear that anything could happen given the perceived corrupting influences of the big city. But there also must have been a strand of wanderlust in my genes, because one of my great aunts ventured to California to pursue her dream to dance and act. She somehow made it despite the challenges of her day. How would I know whether I could be successful at my venture if I didn’t try?

That does not mean that I do not get a queasy feeling every time I decide to shift directions. But I close my eyes, take a deep breath, remember that the feeling will pass (eventually), and then make the first step. No matter where I end up, the journey has always been worth it and has made me more comfortable with accepting what I do not know in order to continually move forward.

- Look for ways to bridge the gaps. To bridge the gaps between people you have to understand where there are gaps and why. Obvious differences such as race, gender, and age are easier to address given various levels of “diversity training” offered today, but other cultural influences that are often not easily discernible offhand also shape a person’s views. Opposing beliefs or mind-sets tend to emerge through casual conversations and informal networking. Gaining an awareness of those differences equips you with areas to focus on in order to better relate to colleagues.

I realize that human nature allows us to make assumptions about others when we do not know or understand enough about them. I was perceived as a potential threat by some in Germany because my skin color was different. However, there was almost immediate acceptance if my onlookers discovered I was an American. In fact, I had more in common with them than they would ever have thought. That also translates into the workplace, where far too often I have been the youngest, the only person of color, the only female—or all three.

There are, however, commonalities underneath the surface of those obvious differences. It is too easy to get distracted if you become stuck focusing on what separates you from others versus what connects you. I have understood the value of leveraging the unique skills, talents, and perspectives each person contributes to a team. Having a diverse workplace requires a comprehensive understanding of all facets of an individual to truly embrace the new diversity that transcends generations and a demographic checklist.

- Do not forget to pay it forward. Exposure to completely different environments and social issues has had a transformative impact on me. I grew the courage, confidence, and resolve to make decisions and test uncharted waters personally and professionally. Without that experience, I probably would have still succeeded in my endeavors but remained in the South, in my comfort zone.

I feel it is my responsibility to encourage others by helping them recognize that they cannot grow unless they realize they don’t have to fit in any predefined box. I am an advocate for study-abroad programs because of the immense opportunities they offer to expand one’s horizons. It opened doors for me that made me a more complete person and deepened the core beliefs and values that make me who I am—regardless of the country, the culture, or boardroom I occupy.

And now that I manage people—primarily those under-thirties who are rising leaders in business—I’ve developed a few rules of thumb for helping them succeed as well:

- Reevaluate how well you know your colleagues and managers. Learn about each team member individually and their interests versus assuming certain stereotypes or gross generalizations. With the proliferation of information on the Internet and social networking, you can easily find out more about others informally and share experiences by joining and using the sites yourself.

- Be open to other viewpoints, and expect to be surprised. Even though you won’t always agree with a different perspective, you can often learn a lot just by listening to alternative approaches to situations. It is easy to think you have “the answer,” but life encounters teach us there is more than one solution. Many paths can lead to the same destination. Given an appreciation for history and the experiences of others, you do not always have to reinvent the answer when something has been proven effective in the past.

- Understand that although change is inevitable, not everyone adapts at the same speed. With the evolution of virtual workplaces, there are new ways of communicating and working together. These methods are effective only if everyone uses and understands them. It is just as important to have an awareness about the impact change has on others on your team as it is to understand the change itself. How you respond and help others adapt will demonstrate your capabilities as a leader. And understanding a person’s heritage or background can be essential to a deeper understanding of the ways they can understand and adapt to change.

Since my parents first entered the workplace, I have noticed changes that allow me to be bolder with who I am and what I expect from others. Blatant discrimination is not tolerated today. My generation grew up in a fully integrated society and benefited from diverse experiences. I can easily reference many successful role models in business and politics with nontraditional backgrounds. Companies have taken steps to teach employees about diversity and how to handle sensitive situations. They recognize in this age that you cannot mask who you truly are and maximize your productivity at work. Self-awareness and cultural acceptance are critical elements of feeling confident with yourself and treating others with respect.

As business professionals in the twenty-first century, we should recognize that the new diversity encompasses a breadth of attributes not constrained by race, gender, and other stereotypical factors. It requires first embracing and celebrating the essence of who you are before you can appreciate what others bring to the table.

Diversity Day

Whole People, Whole Organizations, and a Whole New Approach to Diversity

JOSH BRONSTEIN has been a human capital consultant since 2005, specializing in talent and change management strategies. Josh holds an MBA from Harvard Business School and a bachelor of science in industrial and labor relations from Cornell University. He is passionate about helping people bring more of themselves to work.

In the first season of the hit television show The Office, an episode about “Diversity Day” pokes fun at a tacky diversity training session that teaches employees to become HEROs through Honesty, Empathy, Respect, and Open minds. The comedic routine highlights the skeptical views most employees have toward an outdated view of “diversity.”

When many of us think about diversity, we think about these silly, overdramatic sensitivity training sessions that have been the subject of such ridicule. We think about nondiscrimination policies that exist on paper but allow the highest-revenue producers to opt out. We think about affirmative action and hiring a greater number of underrepresented minorities or women. Or perhaps we think about the most tangibly strategic efforts in which organizations mirror customer or client segments, such as Hispanic or LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender) marketing efforts, to increase revenues. Most people think about these manifestations of diversity because most leaders who came before us viewed workplace diversity in the context of affirmative action, litigation avoidance, or access to diverse markets. But these views of diversity are evolving dramatically.

In conversations with my peers, I’ve realized that our generation believes that such diversity practices are simply table stakes. Of course, it’s still important to ensure employers aren’t discriminating and that individuals are sensitive to the way they treat each other at work. Such practices are necessary, but not sufficient. Our generation wants to lead companies that willingly celebrate a broader definition of diversity in order to galvanize top talent who can deliver better business results.

Value of a Broader View of Diversity

I was twenty-five years old and a relatively new employee. After discussing some time off I was requesting for an upcoming family vacation with “significant others,” my manager asked me in a crowded, open team room, “How long have you been with your girlfriend?” I could play the pronoun game and say “I’ve been with her for two years.” Or I could tell the whole truth. I grabbed a piece of paper and quickly scribbled “boyfriend—2 years.” “Oh, cool,” she responded.

In hindsight, I made the right decision. The energy required to hide my identity from those who I assumed wouldn’t like it distracted me from the work that I was being paid to do. Since then, being openly gay has only helped me professionally—I’ve benefited from a stronger sense of community and a professional network that spans functional silos, more confidence when speaking with senior leaders, and the comfort of always being able to use accurate pronouns.

As a human capital consultant and former leader of the LGBT student association at HBS, I’ve spoken with dozens of general managers, HR leaders, and peers about the role of diversity in a wide cross-section of companies. There are tremendous variations in how diversity and inclusion efforts play out across companies and geographies, but in all of my discussions on the subject my consistent observation has been that diversity is no longer defined by typical indicators such as gender, race, or religion. I’ve realized it takes a broader view of diversity to foster an environment in which everyone feels comfortable telling the whole truth, scribbling—or maybe even outwardly discussing—their diverse backgrounds, experiences, and individual situations, even if those attributes don’t fit neatly into the categories previously associated with “diversity.”

Employers today realize that to remain competitive, they must attract, motivate, and retain individuals from a wider range of experiences, and look for diverse geographic origins, socioeconomic backgrounds, academic experiences, personality types, sexual orientations, generational views, ways of thinking (left brain/right brain, e.g.), and styles of communication. They also realize that by removing constraints that may have deterred applicants in the past, the broadest view of diversity will attract the largest talent pool from which to find the best and brightest future leaders.

By fostering discussions out of differences, we can all challenge the status quo and help our colleagues think outside of the traditional constraints placed on them. Doing so also develops increased intellectual rigor through vigorous debate and a well-rounded ethical compass by avoiding groupthink. The companies that can extend this broader view outside of the United States can also enable enhanced global mobility among diverse high performers.

And let’s not forget the human element—a big component of the value proposition for diversity investments and the broader view of diversity, is that it is simply the right thing to do. How hard was it, really, for my manager described above to react supportively? In today’s business world, collegial values and supportive, strong leadership go a long way.

Redefining Professionalism

To make this new view of diversity work, our generation is prepared to bring our whole selves to work, being open in the workplace about differences in our backgrounds and feeling comfortable enough to resist the temptation to force-fit ourselves into a preset definition of a stereotypical “professional.” This isn’t easy or always comfortable for employees or managers, but true professionalism requires incorporating differences in an inclusive way—not hiding them.

In the past, decision-making authority was limited to a few suit-wearing executives, usually white straight males from prestigious backgrounds. As a result, some employees have been guided to act more “masculine,” more “straight,” or even more “white.” Some managers have historically hidden these suggestions under the guise of encouraging employees to act more “professionally.” But business is inherently personal, not just professional. Our relationships drive our success. And our individualism drives our relationships.

Now more than ever, work and life have converged. With ever-longer workdays and technology—like Facebook and Twitter—that puts us “always on,” we are forced to discuss our work-life balance needs with our managers, and we encourage our employees to do the same with us. Avoiding the subject of a same-sex partner, a child at home, or one’s involvement in certain religious activities takes valuable energy away from the work at hand. It can also be considered untruthful.

Rather than fight this convergence between work and life and calling it “unprofessional,” as many of our predecessors did, take the opportunity to discuss and embrace personal differences in your professional life. Those distinct qualities that make up your identity, beliefs, and situational characteristics arm you with a very unique perspective from which to view business challenges—and hopefully arrive at less traditional and more value-adding solutions. Lead by example—telling the whole truth about who you are—and encourage your employees to do the same.

Authentic Leadership

As the LGBT Student Association’s liaison to admissions, one of my primary tasks was to organize an LGBT open house for prospective students. I knew that the attendees were in for a real treat when Frances Frei—one of the most remarkable, inspirational individuals I’ve ever met—agreed to deliver the faculty address. As the first openly gay tenured HBS faculty member, Frances spoke about LGBT life at HBS, as well as the academic experience, the section experience, and other subjects. But when the million-dollar question came up—should you be “out” in your application—she brought it back to the school’s mission: educating leaders who make a difference in the world. Leadership, Frei has repeatedly argued, fundamentally requires authenticity. And authenticity is tough to demonstrate when you’ve buried the truth deep in the closet.

My call to action for our generation is simple: be authentic. That means bringing your whole self to work, not just those characteristics that you think your employer wants to see. Because as Frances Frei taught me as a teacher and a mentor, being true to yourself and your colleagues will enable you to lead more effectively.

Generation Why

A defining characteristic of our generation is that we want to be recognized as individuals—not anonymous cogs forced to think, act, and dress in the same way.

We see Steve Jobs dress in jeans and a black turtleneck and we wonder why we can’t wear an outfit to work that reflects something about our individualism. We saw the meteoric rise of Sarah Palin, embracing her status as a “hockey mom” and articulating the value such experiences would add to her leadership, and wonder why we can’t do the same. For the first time in history, our generation has seen countless examples of very successful leaders succeed because of their differences, rather than in spite of them.

We also believe that anyone who can address a business challenge in a respectful, intellectual, and honest way is acting “professionally,” even if it means disrespecting the traditional hierarchy. As a part of this new view of diversity, therefore, organizations must flatten. Young leaders are notorious for impatience. As such, we’re empathetic to junior employees who don’t want to wait until they reach the top of the corporate ladder to contribute their unique ideas; we didn’t want our ideas to be held back by our age, and we don’t expect to hold back those who come after us.

Most of us also realize that with the acceleration of technology, some of our knowledge will be outdated by the time we reach the c-suite. For example, it was just a few years ago that texting and social networking were exclusively for social use, making it highly inappropriate for a young employee to text his boss or add her as a friend on Facebook. Today, executives at all levels use text messages and social media to communicate with us. We realize that trends in communication styles must evolve. Based on these experiences, our generation will be even more open to diverse communication styles as they emerge in the years ahead, no matter how foreign they may seem to us by the time we’re middle-aged executives.

As the next generation—“Z” or “I”—enters the workforce, we want to engage them early. Organizational flattening is a critical component of generational diversity that will enable us to take full advantage of the youngest and most creative talent pools. We understand the need to do so because we lived through the greatest technological advancement in modern corporate history, and we saw how some of the most successful companies were those who kept their youngest talent relevant.

Managing Differences

But all of this doesn’t mean that we should be encouraging everyone to conform to the new definition of nonconformity. For example, Steve Jobs can wear his typical jeans and black turtleneck outfit, but if everyone had to do the same to conform to Apple “culture,” employees wouldn’t be bringing their whole selves to work. If a single woman is surrounded by working mothers and made to feel like an outsider for not having a child at home, then the benefits of bringing her whole self to work are negated. If an LGBT-friendly culture becomes so LGBT focused that a straight employee feels uncomfortable bringing his whole self to work, the organization will have a serious talent problem.

The new view of diversity requires a delicate balance that enables employees of all talents to bring their whole selves to work and to acknowledge—and work through—the inevitable conflicts that might arise from doing so. The moment an employee feels uncomfortable bringing his whole self to work because others are doing the same is the moment the leader must interject to regain balance. Without such leadership, the business case for this new view of diversity falls apart.

What Can I Do?

As a young leader, there are a number of steps you can take to be on the forefront of the next wave of diversity strategies. First and foremost, lead by example. Bring your whole self to work. Talk about your family—traditional or nontraditional. Bring your background and experiences—traditional or nontraditional—to the conference room table. Your authenticity will be contagious.

Second, articulate to senior leaders how differences drive success. Refresh the business case for your company’s diversity investments to focus on bringing the most varied views to the table to foster innovation—which is forward thinking— rather than being obliged to find employees who fill in boxes on your diversity checklist—which takes your organization a step back. As a hiring manager, bring this view to life. Hire truly diverse employees with unique backgrounds and perspectives that will help you grow your business, not just those individuals who will help you to meet your diversity targets.

Third, take ownership over fighting the hierarchy. Diverse ideas flow best when there aren’t consequences for sharing them, and hierarchies inherently create such consequences. Plus, the youngest talented employees are also the least influenced by “the way things have always been done” and often have some of the most diverse perspectives. This isn’t easy: it takes young leaders to articulate this strategy and cooperative, secure senior leaders to facilitate it. Make the case and push hard.

Fourth, embrace a variety of communication styles and mediums. Organizational communication mechanisms evolve. The more you use emerging technologies for business communications and spread such trends to your peers, the more responsive your organization might be. Beyond technology, a broad view of diversity takes a range of information processing styles into account when communicating key messages. The most creative and varied styles of communication, rather than the loudest, cut through the information clutter within organizations and reach a variety of people who don’t all learn and interpret information the same way; therefore, push your organization to vary communication styles and mediums. At the very least, do so with your own communications.

Finally, reward individuals on your team for bringing their unique perspectives to the table. A few words of praise for having the courage to talk about a relevant personal situation or experience in a meeting can go a long way—and the positive impact can spread throughout the organization.

The business case for expansive diversity is gaining strength—gone are the days when companies hire a few more underrepresented minorities, hold a “Diversity Day,” and call themselves “diverse.” A diverse workforce of the future will be an innovation machine. Such an organization will be armed with individuals anxious to share their unique experiences, beliefs, and backgrounds to create value.

Help your company stay relevant by redefining its view of diversity to create a truly inclusive culture, and ensure this culture permeates your operations across geographies. Doing so will motivate existing employees by enabling them to bring their whole selves to work no matter where in the world they are, and will attract the best and brightest new talent who want to do the same. As a young leader, it starts with you.

Women and the Workplace

After graduating from Wellesley College, TASNEEM DOHADWALA joined an equity sales strategy team at Lehman Brothers. She left to join the Nooril-Iman Foundation, where she executed a program of economic self-sustainment in Myanmar and construction of a medical clinic in Yemen. After graduating HBS in 2009, she cofounded Excelestar Ventures. She reflects on the evolving roles and expectations of women in business.

In my first year at Lehman a respected and successful female senior manager reprimanded my male manager in a meeting. As we were leaving the meeting he told me, “I like my women as I like my coffee—with milk and sugar.”

I responded, “But she gets things done.” This woman, like so many others in similar positions, needed to maintain a firm approach, but often got stereotyped and ridiculed in the process.

There’s little doubt that women now have greater access to the upper echelons of the business world than they did fifty, thirty, or even twenty years ago. The fact that I could respond to my manager’s comment without any tangible repercussion is evidence of that advance; but the fact that he even made the comment is a microcosm of the work that remains to be done. Access to the business world for female professionals has too often hinged on conforming to the expectations of male colleagues and managers. In some cases, male counterparts expect women to remain feminine and not be one of the guys. In other situations, men expect their female colleagues to conform and be one of the guys. It has been the woman’s job to figure out what her colleagues and managers are expecting, consciously or subconsciously, and project that as her personality. Regardless of which bias exists, it is almost impossible for a female professional to receive the same level of “brotherly” inclusion.

Further, because of the current constraints inherent in today’s business world, women are often compelled to choose between work and family more explicitly than men are. They are not rewarded for efficiently balancing both. As Elizabeth Gudrais noted in the February 2010 issue of Harvard Magazine, “Women have undoubtedly made gains in terms of access to business careers . . . But in terms of being able to choose careers they want within those fields, as opposed to having to abandon professional goals for the sake of family, women still have far to go.”10 In many cases, women discover that trying to balance work and family results in a muted professional life. When a woman’s scale tips in favor of work, people often assume that work is her only priority. As a result, many women choose family. A survey of 6,500 Harvard and Radcliffe graduates revealed that only 30 percent of female MBAs worked full-time, year-round and had children, while 45 percent of MDs did.11

Currently, many organizations accommodate the specific circumstances of female employees. Usually, this involves flexible work arrangements, maternity leave, and day care facilities. Unfortunately, these are peripheral solutions to the lack of gender diversity in businesses, especially at the top. It’s incumbent upon the next generation of female business leaders to forge their own rules based on a female-centric value system. Only after the rules of business are rebuilt to incorporate such a value system will businesses truly be able to harness the talent of all their employees. These values involve

- Rejecting the false choice between family and professional success

- Breaking down artificially forced gender roles

- Changing how women view themselves in the workplace

These are difficult issues to discuss because they question deeply held assumptions about the role of women, the nature of meritocracy, and how we reward people in our organizations. Turning conversation into action is a two-way street. Not only must organizations understand what young female professionals hold dear in order to truly capture the value they bring, but women themselves must also strive to better articulate and champion their values in the workplace.

First, the next generation of female leaders must break down the false choice between career and family. Like it or not, for biological and social reasons, women are often positioned as primary caregivers in their families; and that position often involves trading success at work for stability at home. The next generation of women and employers must work to erode this trade-off. This starts with openness. Companies should become more proactive about making female managers available to female candidates to discuss openly how female managers balance family and professional success within the firm. Female candidates must become more comfortable raising these questions explicitly. When I interviewed with the CEO of Care.com, Sheila Marcelo, she described several instances of Care.com employees proactively balancing work and family. For example, she told me that the CTO worked from Greece and the head of business development took every Friday off. It seemed to me that her willingness to allow employees to create their own work experience enhanced their commitment, work ethic, and productivity. Unfortunately, in the current context, female candidates often do this more covertly, asking other women who work in the company about the “rules” around balancing family and work. Candidates shy away from asking about what they can expect of the quality of their personal life because they feel that they will be adversely judged. Companies can start to implement this openness by instructing HR professionals and managers who conduct interviews to describe the various degrees of flexibility available to the candidate and directly ask the candidate what they need to achieve work-life balance.

They of course shouldn’t be adversely impacted for prioritizing both the personal and the professional. Rather, women should be rewarded for successfully balancing both family and work (as, incidentally, should men). Women should feel free to bring their “authentic” selves to work—whether that concept of self involves family or not—and employers should create space for those discussions.

Second, in addition to valuing women’s ability to nurture both work and family, organizations must make efforts to break down artificially forced gender roles and create organizational sponsorship for women. Often, these are projected by senior management—where the ranks of women are still remarkably thin. Whether a manager’s female subordinate assimilates seamlessly with her male counterparts or asserts her femininity is irrelevant. The matter of significance is that she is able to have her own personality. The proximity afforded to “one of the boys” should also be offered to her. Although women and men are currently both successfully mentored, climbing the ladder demands more than mentorship; it requires sponsorship. This issue was covered extensively in a Harvard Business Review article whose title stated the problem: “Why Men Still Get More Promotions Than Women”:

All mentoring is not created equal, we discovered. There is a special kind of relationship—called sponsorship—in which the mentor goes beyond giving feedback and advice and uses his or her influence with senior executives to advocate for the mentee. Our interviews and surveys alike suggest that high-potential women are overmentored and undersponsored relative to their male peers—and that they are not advancing in their organizations. Furthermore, without sponsorship, women not only are less likely than men to be appointed to top roles but may also be more reluctant to go for them.12

Embracing and utilizing sponsorship is especially important early in a woman’s career. A recent study demonstrated that nearly a quarter of women leave their first job because of a difficult manager, while only 16 percent of men do.13 Because many managers are men, there seems to be an almost subconscious tilt toward being less of a sponsor or “champion” for young female employees—and, while other factors could be at play, this may have a lot to do with why women feel so frustrated with their managers early in their careers. Companies interested in greater and deeper female participation should address this concern head-on, training managers on what it means to be a sponsor, and making sure that women receive such sponsorship the day they walk in the door.

Finally, young women in business must actively participate in the process of rebuilding existing workplace rules, as described earlier. They must reflect and be honest about trade-offs they are willing to make in both their personal and professional lives. This can be hard, in light of the scarcity of jobs. I was interviewing in 2009, an abysmal year for most job seekers. I decided to put together a list of requirements that could help create balance between work and family, and as a result, significantly narrowed my list of potential job opportunities. I did not want a job that demanded never-ending hours, required travel more than 50 percent of the time, and demanded tremendous after hours networking. I looked for a job where some employees were already experimenting with work-time flexibilities and some work could be done remotely and independently, rather than being dependent on going to the office. Though constraining, I was candid with myself and what I valued. I was fairly assertive and conscious of trying to be open with my employers. However, I was not idealistic, as I knew there would be many times when work would demand more from me than home would. Those would be the times when I could not be home in time to read to my son before bedtime. I was certain that there would be many business needs that could only be met in person, demanding travel. Fundamentally, work and family require trade-offs. And as long as both dimensions of my life made room for each other, both would thrive.

Despite what I thought was a sense of realism, when I was applying for jobs I still found myself trying to conceal my pregnancy. I bought suits specifically tailored to hiding my bump. Rather than use my ability to balance both my professional aspirations and motherhood as a testimony to my drive, dedication, and ambition, I suppressed it. In retrospect, I was disappointed in my approach. Only when we are comfortable with ourselves and what we value will others begin to embrace our very real needs. If we conceal our personalities and the multiple facets of our lives or conform to a dysfunctional status quo, organizations will never realize that changes must be made. I felt that being open about my pregnancy would immediately diminish my chances of winning the opportunity as it would give the interviewer the impression that work would always suffer as second to family. I believe if we eliminate the false choice between work and family, women will no longer feel the apprehension I did.

To truly rebuild the current system of values and see a meaningful change in the current workplace ethos, more women in this generation need to be assertive about what they need at work. Women need to emphasize that motherhood does not make work a lesser priority. Rather, female business professionals aim for both dimensions of their life to excel. Managers of companies that truly embrace work-life balance, such as Care.com, and allow employees to create their own workplace experience should speak out about what they are doing and the benefits it brings. Some practical advice for managers of companies that still lag in work-life programs: begin talking to your subordinates about the trade-offs in your life. This should encourage them to start sharing with you. Ask those team members who have families how they manage, especially when times get too hard. If you, as a manager, speak to them, the fear of lack of acceptance will slowly dissipate. Not only encourage team members with families to experiment with programs that are being offered, but try them yourself and then talk about it. The employees who excel at both family and work should be publicly celebrated. Ironically, many business professionals are already successfully balancing work and family, but we do not hear about it because it seems that no one cares to listen.

If we want to see more gender-balanced executive suites, if we want to see greater freedom for men and women to embrace dual roles as professionals and heads of families, and if we want to see a more inclusive set of rules that offer female professionals to be their authentic, whole selves at work, we must take active responsibility for building on the successes of the past several decades. Rebuilding workplace rules around the life realities of both men and women is the challenge for the new generation of leaders and professionals.

Joyful on the Job

A Generation Pursuing Happiness at Work

BENJAMIN SCHUMACHER is from Lexington, Kentucky, and studied psychology at Washington University in St. Louis. Ben has worked in management consulting for Deloitte Consulting, McKinsey & Company, and Instituto Exclusivo in La Paz, Bolivia. He holds an MBA from Harvard Business School and finds happiness working with education-oriented nonprofits.

The unyielding sun melted into the horizon, finally relenting after a sweltering, sweaty day of work in the horse farms of central Kentucky. My hands blistered and my throat parched, I let my shovel fall to the dirt and knelt under the shade of an ancient sycamore next to my fellow irrigation installation crew members, Ariel, Manuel, and Abenamar. Our fifth, oldest, and most experienced member—“Tio” (“Uncle”)—walked to the garage to input the final settings in the irrigation system controller. The evening was closing in on us, and we had scrambled to successfully finish installing a residential sprinkler system before it was too dark to work any longer. Digging trenches, laying pipe, and setting sprinkler heads for twelve hours straight is no small exertion, but there’s a special gratification when a team can point directly to the fruit of its labors. From the garage, Tio flipped a switch, and as the system sprang to life with rotors blasting across the lawn and smaller heads gently misting the gardens, the five of us exchanged grins of satisfaction. We were happy.

This experience at Bluegrass Irrigation, my family’s business, is one of the earliest that got me thinking about happiness on the job. How was it that my parents, entrepreneurs who had no formal business background or training, could create an environment where Tio, Ariel, Manuel, Abenamar, and I could find happiness, but the company’s client who would fly in on his helicopter to monitor our progress seemed so perpetually unhappy? Or, if we are all in agreement that we’d like our bosses, coworkers, and subordinates to be happy (not to mention ourselves), why is happiness so often elusive in the workplace?

I believe it is not the idea of promoting happiness in the workplace that presents conflict to most people. It is the idea of trade-offs: when to prioritize others’ happiness over yours or future happiness over immediate pleasure. In a managerial context, leaders of organizations must make these decisions frequently: how often an employee is allowed to work from home or how much time off to write into company policy, for example. Given the ubiquity of structures in the workplace—cubicles, where to sit, what to wear, scheduled hours in the office, scheduled years to the next rung on the corporate ladder, and so on—it is no wonder that a mental trade-off is manifested: how much time and happiness do I devote to the success of my company and how much do I keep to myself?

But is this traditional trade-off between employee happiness, managerial happiness, and a company’s financial success as robust as it is perceived to be? I had the chance to explore this question inadvertently during the summer of 2009 in La Paz, Bolivia, where I worked at a local language institute, Instituto Exclusivo. After getting over the initial shock of the altitude (12,000 feet above sea level!) and settling into the hustle and bustle of La Paz’s Sopocachi district, the institute tasked me with improving student retention rates. Fresh off two and a half years of operations consulting, I was eager to put my skill set to work. I honed in on the student-teacher relationship and observed several suboptimal practices: teachers weren’t coming to lessons on time, new technologies made available by the institute were not being leveraged for lessons, and the retention rate after students’ first lessons was particularly low. Like any eager consultant, I immediately set to work devising a performance-based incentive system meant to tweak specific teacher behaviors. Bonuses would be given to teachers who were punctual, who implemented technology into lessons, and who consistently kept first-time students coming back for more. However, while getting to know the teachers more personally during my time at the institute, I began to observe an intriguing relationship: teachers who were happy working there, such as three I met—Patricia, Rudy, and Helen—tended to be the top performers. Their students sang their praises, they eagerly adopted new technologies, and they contributed disproportionately to the profitability of the institute. The unhappy teachers tended to be more transient employees whose students consistently complained about their lack of preparedness and commitment, and who disproportionately contributed to the costs of the institute in the form of hiring costs, lost students, and unquantifiable detriment to the institute’s brand.

Upon making this observation, I took the logic chain one step further: if good performance is associated with happiness, what was intrinsic to the institute that made these employees happy? In some cases, it was the opportunity for teachers to arrange their lessons according to their own busy schedules. Patricia worked in a chemist’s lab during the day and preferred giving lessons early in the morning or later in the evening. In Rudy’s case, it was the camaraderie of sporting activities such as futsal (five against five soccer with a smaller, less bouncy ball) that were organized through the institute; and for teachers such as Helen (who migrated from the Netherlands to La Paz in 2006), the institute’s common room was clearly the teachers’ primary space for socializing throughout the week with friends. The point is that whether intentional or not, certain practices of the institute contribute to employee happiness by integrating the “whole person” into the organization, and this, in turn, appears to contribute to greater productivity in the institute’s employees as well.

Although the empirical correlation between employee happiness and productivity is still being researched, job satisfaction has been shown to be positively linked to productivity.14 HBS’s own Teresa Amabile has found that happiness in the workplace provokes greater creativity.15 To me, it also seems intuitively true that I work harder when I’m happy. We all can relate to putting an “extra 10 percent” into an enjoyable activity or toward a commitment to someone we respect (the flipside, of course, appears equally probable: the resentment I feel toward an unsavory task is compounded immeasurably if I’m generally unhappy with my work environment). The question, then, is what can corporate leaders do to increase happiness within their organizations, and, notably, what are some leading-edge companies already doing?

The answers come in various forms and are certainly not as straightforward as a bigger bonus or more vacation time. I believe that for my generation, the notion of the “whole person” is central to finding happiness in the workplace, and thereby giving our best efforts toward the objectives of our employers. A “whole person” is one who feels comfortable bringing his or her authentic self to work each day, especially in a technological world that breaks down barriers between the professional and the personal. A “whole person” is able to integrate the rigorous demands of his job with the rigorous demands of his life—and work more passionately and purposefully as a result. There are a number of tools managers can employ, and young leaders should demand to promote the concept of the “whole person,” thus creating a happier, more productive workspace.

First, we should attempt to formalize flexibility into how employees perform their work. This is all the more important to a generation of marital partners who both hold jobs outside the home. A former employer of mine, Deloitte Consulting LLP, has chosen to implement what its creators call “Mass Career Customization” (MCC). One way MCC plays out in practice is to allow employees to “dial up” or “dial down” certain aspects of their careers. This could include the amount of time spent traveling, the location from which one works, or something as fundamental as hours worked per week. I have a friend who is employed by the Washington, D.C., office, lives in New York, and currently has “dialed down” to half-time work in order to pursue her passions as an author—all with encouragement from top management. Deloitte has bought into the idea that the retention of top talent is worth keeping its top talent happy.16

Recently, this trend toward career flexibility has even manifested itself in the public sector. The Human Services and Public Health Department of Hennepin County in Minneapolis has implemented its own version of MCC, known as ROWE or “results-only work environment.” Defining features of ROWE include location flexibility, clearly defining desired results, and, most provocatively, completely optional meetings (the idea being if the purpose of the meeting is worthwhile, it will be attended). Custodians of the program have cited tremendous productivity gains in activities such as processing incoming mail.17

Second, we should seek to provide an outlet for employees to make a positive impact on people they care about, thus bolstering the traditional employee-employer relationship to a level that yields deeper levels of happiness and purpose. In his book Just Enough: Tools for Creating Success in Your Work and Life, HBS professor Howard Stevenson refers to this as “significance” and defines it as a core component to “enduring success” in life. I was fortunate to work with a Boston-based nonprofit called Young Entrepreneurs Alliance (YEA) that offers this type of program to its corporate sponsors, and it is essential to their value proposition. YEA is a business-ownership program that seeks to alter the trajectory of at-risk teens. As part of its corporate sponsorship program with companies like Staples, YEA receives cash donations; but it also organizes structured learning sessions where Staples employees create training programs for the participating at-risk teens. This has obvious benefits for the teens, but for Staples, it also happens to boost employee morale, promote teamwork, and even serve as a training ground for its workforce. I believe this volunteerism in a team-based setting—supported by management—can be a powerful force in the fostering of general employee happiness through performing “significant” work.

Third, we, as rising leaders, should consider organizing a physical fitness program. As I discovered in my undergraduate research, exercise is connected with happiness—psychologists refer to it as “subjective well-being”—because it burns cortisol (associated with anger or fear) and produces endorphins (associated with euphoria).18 Evidenced by the success of organic, sustainable foods, or even brands like Vitamin Water, a substantial segment of our generation is putting fitness on a pedestal—and I believe it behooves today’s executives to recognize this priority. Some organizations are doing well on this front. Deloitte provides a health and fitness subsidy, a monthly newsletter with healthy lifestyle tips, and annual flu shots to all firm members.19 Both Deloitte and another consultancy, Bain & Company, host annual World Cup soccer events.20

Finally, while happiness is admittedly an abstract concept, this does not diminish the importance of managing it. Since “that which gets measured gets managed,” I suggest managers attempt to track components of employee happiness over time—and address concerns directly when they are voiced. One aspect that attracted me to McKinsey & Company is that the firm measures happiness both on a consulting project level and at a firm level across offices. On projects, a biweekly survey is sent to each project member that gauges reactions to statements such as “I am excited about my experience on this engagement,” “Our working team functions well and there is an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect,” and “Overall lifestyle is manageable on a sustained basis.” Managers closely track survey results and adjust team dynamics accordingly. At the enterprise level, firmwide surveys gauge relative happiness levels at each office. It may not be a coincidence that the happiest region in the firm is simultaneously one of the most profitable.

In retrospect, perhaps my parents were precocious in the design of our family’s small irrigation business. Employees are paid a wage above market rate that they send home to needy families, thus performing the “significant” work of positively impacting those they care about; the job certainly requires physical fitness, as I discovered by the sycamore tree long ago; while sunlight hours aren’t very flexible in terms of work hours, at least breaks and lunch schedules always are; and my parents have been successful in establishing an informal culture of monitoring employee happiness and actively addressing concerns. If the employees at Bluegrass Irrigation can be happy, so can the employees at any organization, and I believe that understanding, promoting, and measuring employee happiness will be paramount in transforming the workplace for our generation.

People Leadership from Baghdad to Boston

SETH MOULTON graduated from Harvard College in 2001 and served four tours as a Marine Corps infantry officer in Iraq, two as a platoon commander and two as a special assistant to General David Petraeus. In 2011, he graduated with a joint degree from Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Business School. He is passionate about service and bringing his experience in the Marines to bear in the private sector.

Tom Brokaw, author of the iconic Greatest Generation, a tribute to the men and women of our grandparents’ era who fought in World War II, looked at a group of young Americans in 2003 and said, “This is the next greatest generation.” But he wasn’t looking at a group of Harvard or Princeton graduates, or at a group of business or technology leaders, or at a championship sports team. He was looking at a battalion of soldiers in Iraq. There he saw young Americans so dedicated to the ideal of service that they were actually putting their lives on the line to serve. They didn’t just speak of service, or believe in service—they were actually doing it.

I was one of them, serving in Iraq, and transitioning to the business world hasn’t been easy. At twenty-three, I was intimately responsible for the lives of forty young Americans, and also responsible for life-or-death decisions affecting those we met on the streets of Iraq. Settling into a classroom seat at Harvard in many respects felt boring, inconsequential, and self-serving in comparison.

But it wasn’t as I expected. I thought I would return from five years serving in the Marine Corps to a crowd of unappreciative classmates, thankful that they were well ahead of me on the path to personal wealth. Harvard, after all, didn’t even allow ROTC on its campus until recently.21 But instead of receiving a cold shoulder, I was pleasantly surprised by the respect the community showed my fellow veterans and me. Many of my peers were even envious—not of the horrors I had seen in the war or of the diminutive size of my bank account—but of the fact that I had experienced something so consequential early in life and that I learned something unique about leadership in the process. Every day I made decisions that profoundly impacted the lives of young Americans, and of Iraqis. Even the staunchest opponents of the Iraq War scarcely had the impact on the lives of others that I did on the front lines. And those experiences forged in me and in my fellow marines a sense of pride and camaraderie in our work as well as an appreciation for the difference that individual leaders can make.

So why give up that sense of purpose and service to head into a world defined by profit-seeking and self-interest? Sometimes I have to step back from the emotional pull of the war to remember that while, sadly, fighting wars is critical to our national survival, it is not what America is fundamentally about. America is a free country that thrives on the backbone of its free economy. It is a country built by individuals engaged in free enterprise, and our economic history is by far more important than our military history. I am proud to be a veteran of our country’s armed forces, but I am anxious to be a part of this other fundamental part of America as well. Business requires good leadership, just as the Marine Corps does. And as I transition from the Marines to the private sector, I hope that I’ll be able to take some of the lessons I learned in combat to my colleagues in the boardroom—even as they teach me something about what it takes to power an economy that keeps our country strong.

In the Marines, I learned that good leadership is about two fundamental things: accomplishing the mission and taking care of your men. Accomplishing the mission is straightforward: it’s something every leader needs to do, and America could not have built the great companies of the twentieth century or won its battles overseas without business and military leaders who knew how to get things done.

But the real key to success in leadership is doing it in a way that also ensures the survival and success of the men and women who work for you. Sometimes I think that much of our business community has forgotten this lesson—as Wall Street has become infamous for its excess, companies have emphasized short-term results over long-term investment, and the gap between executives and labor has only increased.

For me, “taking care of your men” in wartime was simple when it was just the forty young men in my platoon. But soon after the invasion, I found myself leading not just a platoon of marine infantrymen but a neighborhood of Iraqi men, women, and children. Suddenly, all eyes turned to young Lieutenant Moulton when it came to solving local crime and paying the police, restoring electricity, and explaining what the Americans intended to do with the Iraqi Army we put out of a job. The impossible diversity of the task was daunting.

Business leaders face a similar mandate when their influence extends beyond their companies into their communities. At the big General Electric plant not far from where I grew up, good management requires not only providing competitive wages and reliable health care for employees, but also stewardship of the marshes and waterways that flow past the plant. Indeed, it is leadership beyond your mandate, taking care of not just your subordinates but your community, that often defines real success. What would Rockefeller mean to us today if he had kept his money to himself, or who would know the Kennedys if they simply enjoyed their house on Cape Cod? Bill Gates is an obvious contemporary example, somebody whose passing fame as this moment’s wealthiest person now has the potential to become lasting fame for what he is doing to fight world health problems. He has lived most of his life amassing a personal fortune and bringing productivity to the workplace; now he is saving thousands of lives. Businessmen and women would do well to remember that whether through service, sacrifice, or simple philanthropy, most of the greatest business leaders in history are remembered not for what they earned, but for what they gave back.

Finally, there was a third leadership lesson I took from the Marine Corps that perhaps wasn’t as important as the first two, but upon which the success of the first two often depended. That was the importance of exercising humility, and it was something I relearned countless times in the war. Faced with new challenges every day that I could not anticipate, overconfidence was sure to lead to failure, so I had to listen a lot, learn from both my most senior commanders and most junior men, and never rest on past success. In my little neighborhood south of Baghdad just after the invasion, my translator, a former officer in the enemy I had just fought against, became my most trusted advisor. So many times when Iraqis and Americans alike looked to me for answers, I turned to Aiyid. He was a humble man himself, for despite being a proud colonel in the Iraqi military, he drove up to me in a minivan—a man half his age and half his rank, and his former enemy—to ask for a job and volunteer to help. The humility we showed to each other was the foundation of whatever success we had together in serving the people of that neighborhood, and it has defined our friendship ever since. In a business world that has become known by the hubris that led to scandals like those that brought down Enron and WorldCom, as well as the recession of the last few years, I have to believe a similar humility would serve our economy as well.

The challenge for me—for each of us—is to take what I have learned through my own set of diverse experiences and use those lessons to become a part of forging a bright future for our country, a future defined not just by the profitability of our companies but by the role those companies play in the welfare of those they serve. When America’s “greatest generation” returned from World War II, they led the nation from the home front into the greatest period of growth and prosperity the world has ever seen. Today’s veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan stand alongside veterans of Teach for America, the Peace Corps, and other civilian service veterans as part of a much smaller minority in a country that values service, but doesn’t always serve. I hope that this new generation of veterans who bring their own diverse experiences to the business world can have a positive influence on the American business that makes our country great, offering leadership that is guided not just by the prize of success, but by the ideal of service.

INTERVIEW WITH . . .

Deb Henretta

Group President, P&G Asia

Deb Henretta talks about the importance of purpose and diversity at P&G, the defining characteristics of next-generation leaders, and how businesses can best adapt to utilize their strengths.

How has the concept of diversity evolved at P&G? What are the biggest changes in the company’s approach to diversity?

While not always called diversity, P&G has been involved with diversity since its founding days when the P&G founder James Gamble supported education of U.S. minorities. Over time, it’s taken many forms. Historically, the initial focus was on representation numbers for several groups. In more recent years P&G is focusing not only on diverse representation, but also inclusion so that every employee feels valued and included, so that they can perform at their peak.

What are the challenges that you face in leading a multicultural P&G organization in Asia? What have you done to address these? What works and what doesn’t?

Having a multicultural organization is a strength. The fact that our twenty-one thousand employees in Asia belong to sixty-one nationalities is a clear advantage as we try and bring to life our purpose of touching and improving more consumers’ lives in more parts of Asia more completely. Today, we serve 2 billion Asian consumers across forty-three markets, and this number is growing. It is critical that we reflect this diversity among our employees to be able to serve our consumers effectively.

However, it is indeed important to institutionalize systems and processes that harness the best of this diversity while ensuring that we remain consistent with our global purpose, values, and principles. For this we have adopted an approach that we articulate as “As common as possible; as different as needed.”

So while our success drivers, appraisals, and all key trainings are standardized and globally deployed, we also focus on critical and uniquely Asian capability needs. These are related to the effectiveness of Asian leaders to lead the diverse, multicultural teams within Asia and influence their global counterparts outside Asia.

More than any other part of the world, leaders in Asia have to constantly adapt their leadership style to inspire and motivate each of the diverse cultures and countries that comprise Asia. Using a single leadership style will prove insufficient given the differences in culture, motivations, rewards, and definitions of success in the different countries. Only leaders who can understand and adapt to these local cultures will grow into truly successful pan-Asian leaders. At P&G, we have established a multicultural program that equips our Asian leaders with deep understanding of how cultures work in a business context and, equally importantly, with skills to “style switch” as they interact with employees from different cultural backgrounds.

What new forms of diversity are emerging in such a vibrant and fast-changing part of the world?

Asia is home to one of the youngest populations in the world. This has led to a whole new demographic that we call Gen Y and define as those under thirty years of age. In P&G Asia, every one in two employees is a Gen Y’er. Frankly, this changes many things. Gen Y employees have very different attitudes compared to, say, my generation. I see this shift having three clear characteristics, which in turn spur a chain of effects at the organizational level:

- Y-Not: Gen Y employees question status quo. They like challenges and they will not accept a no simply because their manager tells them so. In a way, this is great because it gets the more experimental and innovative thoughts into the room and forces the organization to embrace change faster than it would have otherwise.

- Y-Fi: The second impact of the rise of Gen Y as a demographic is an increase in digital diversity. To them digital is not a skill that they need to adopt. They are digital. Their immersion in Web 2.0 and technologies is seamless and holistic. This forces the larger organization to speed up its own digital journey to being digital native. In P&G, we have formalized reverse mentoring programs where Gen Y employees induct older, more senior leaders into the digital way of life.

- Y-Go: Gen Y employees like mobility and flexibility. Nine to five doesn’t work for them. That doesn’t mean they are any less productive. In fact, they are used to being connected 24/7 and can prove to be much more productive if you let them do it their way. At P&G, we have programs like flextime and work from home that try to accommodate this aspect of the Gen Y personality.

A lot of people are writing about the concept of “joy” or “happiness” at work. Do you think that thinking broadly about diversity can help people find more wholeness and happiness at work?

This goes back to the impact that Gen Y employees are having at the workplace. Traditionally, we used to find that most of us have two identities. One that we brought to work, and the other that we kept outside. We find that Gen Y has an integrated identity that is consistent between workplace, home, and society. For example, their concern for the environment or social responsibility is not extraneous to who they are as a marketing or a finance employee in the office. So they not only want to make a difference themselves, they want to know that the company they work for is also making a positive contribution. Similarly, they expect to be able to spend adequate time cultivating the different sides of their personality and not be at the office working late nights. So, they have clear expectations of work-life balance. We have tried to take all of these expectations to create a holistic Employee Value Proposition (EVP) that goes much beyond the traditional compensation and benefits approach. The P&G EVP, which was awarded the 2010 Asian Human Capital Award, consists of six pillars, including such intangibles as “pride in company,” “relationship with manager,” and “work-life effectiveness” in addition to the more defined ones such as “fair and competitive reward” and “learning and development.”

I believe that such an EVP builds in such expectations as joy and happiness.

You see a lot of young leaders in your organization, and it’s arguably a more diverse generation than any in recent memory. But are there any blind spots that this generation has about diversity? What should they look out for?

I think the answer to that is balance. As I have said, generational diversity is great because it forces us to embrace change faster than we may have otherwise. However, it is important to hold on to the good practices that we have arrived at today and be guided by time-tested principles. For us, our purpose is that guide.

We have lived by it for 174 years—that’s nearly ten generations! Our purpose is to touch and improve lives, now and for generations to come. Our growth strategy today is inspired by this purpose: to improve the lives of more consumers, in more parts of the world, more completely. Today we serve over 4 billion consumers; our goal is to serve 5 billion over the next five years. That means we will have to serve all types of consumers, in all parts of the world irrespective of what the personal blind spots of a younger generation of employees may be.

What challenges remain for women in the workplace, and how is this changing over time? What has P&G done to address this?

Globally, issues such as the balance or integration of work and home life continue to be a challenge not just for women, but for men as well. We have put in place various programs for workplace flexibility to help provide alternatives and choices for employees to alleviate the challenge of managing the blend of their work and home life.

How do you see the future of diversity initiatives, inside and outside of P&G? What will a truly diverse organization look like twenty years from now?

For P&G, our principle-based purpose and approach to diversity will continue, aiming to foster a culture of inclusion with respect for all individuals. We want to attract and retain diverse talent throughout the organization, and support our employees by providing a flexible environment that enables them to perform at their peak. We expect diversity and inclusion to be effectively and sustainably integrated into P&G’s DNA throughout our people processes and accountability systems as well as our external and internal partnerships. We recognize that everyone is unique in their background, whether it be gender, geography, physical challenges, or ethnicity. We want to touch the lives of our employees one person at a time. Enabling our employees to share their diverse skills, passions, and experiences will enable us as a company to leverage their talent to the fullest and give us a competitive advantage to deliver against our growth strategy and touch more consumers’ lives, in more parts of the world, more completely.

Simply put, everyone valued, everyone included, everyone performing at their peak.