8. is your company ready for HEROes?

Rachel Nislick and Robin Saitz just wanted to find a new way to reach out to customers. It wasn’t their intention to transform their company, but that’s what ended up happening.

Rachel is an energetic young woman who runs the Web site for PTC, one of the largest providers of CAD (computer-aided design) and PLM (product lifecycle management) software in the world. In late 2007, she conceived the idea of creating an online community for PTC’s customers. As we described in chapter 3, communities have significant benefits, including helping customers to get support, opening up an environment to sound out new product features, and surfacing enthusiastic customers who can become valuable company advocates. So Rachel brought her idea to Robin, her boss, who is an ex-engineer, a senior vice president in PTC’s marketing department, and a twenty-year veteran of PTC.

Robin was a believer in the power of the groundswell, so she was receptive to Rachel’s idea. The idea percolated for a while. By 2009, the two of them had even picked out a vendor to build the community—Jive Software. Nearly everything was in place except for one important element: buy-in. As the project became more visible, executives from all over the company expressed concerns.

For example, Paul Lenfest, the head of customer service, knew much of the company’s revenue came from maintenance contracts, and wondered what the community might do to that revenue stream. Steve Horan, who was PTC’s CIO at the time, foresaw problems, too. “I am a huge proponent of communities,” he said at the time. “But the challenge is they have already chosen the technology.”1 From his experience with PTC projects in other departments, Steve was worried that the marketing team hadn’t fully scoped the requirements for IT personnel, support, and funds.

With these organizational dynamics, Rachel and Robin knew they would get nowhere unless the whole organization could come together behind their plan. Here’s how they did it.

First, they decided to stop guessing about the customers and ask them. Our company, Forrester Research, helped them field and analyze a survey that reached over seven thousand customers and prospects. Results of the survey: PTC’s customers were overwhelmingly ready to embrace a community.2 I (Josh) presented this information to many of PTC’s senior managers at a meeting at the company’s Massachusetts headquarters. The executives asked a lot of questions, and the data helped calm some of their concerns. But the plan wasn’t out of the woods yet.

PTC’s IT and marketing groups collaborated to create detailed community requirements and a deep technical review of the technology platform, Jive. They looked at alternatives that might fit better with PTC’s other technology priorities. In the end, Jive won out, but the difference was, the important technical decision makers at PTC had now bought in on that decision, and the company had a more rigorous perspective on what the software would have to do—and how the value would be measured.

This technical review also gave Robin and Rachel time to win over others in the company. Importantly, they won over Jim Heppelmann, the company’s president and COO and a highly respected leader with both customers and staffers. As they geared up to launch the community, momentum was clearly building; product managers who had previously been skeptical started to ask when their products could be included, too. The CMO, CIO, and head of customer service all came on board because Robin had done the work to prove the plan was solid and would have a positive impact on PTC’s business.

Between Rachel’s original idea in 2007 and the community’s launch in 2010, the conception of the community hadn’t changed all that much. What had changed was PTC itself. In 2007, Rachel was just a woman with a cool idea for customers. In 2010, PTC was a company that knew how to align all of its contending groups behind a couple of HEROes. Both the project and the company were stronger for it.

the two things your company needs to make HEROes effective

The story of what happened at PTC is typical. HEROes don’t just get an idea, line up support, and implement it. They can succeed only with the company behind them.

Building a HERO-powered business is hard. Is your company ready for it?

In the previous chapter, we described how IT, managers, and HEROes need to work together to create the HERO-powered business. Empowered workers are not enough; they can succeed only in a culture that encourages them and supports them with resources. At PTC, the resources were there, but the culture—the leadership—needed to come around to support and guide the ideas Rachel and Robin had started with. At other companies, the encouragement and guidance is there but the resources are locked down. Either flaw can stop HEROes from contributing effectively.

So we have identified two key dimensions of readiness—workers feeling empowered and acting resourceful. We created an instrument to measure them. Using our survey of 4,364 information workers in U.S. companies, we analyzed workers by company, by industry, and by job description on these two dimensions:

- Do you feel empowered? We asked workers whether, when it comes to technology at work, they agreed with the statement, “I feel empowered to solve my own problems and challenges at work.” Because most people were inclined to respond positively to this statement, we counted someone as feeling empowered only if their response was eight or higher on a ten-point scale.

- Do you act resourceful? As we saw in the previous chapter, allowing employees to use devices, applications, and sites that aren’t sanctioned by the company is a key prerequisite to their ability to act resourceful. So we measured whether individuals had downloaded and regularly used at least two unsanctioned applications to their PCs or regularly visited at least two unsanctioned Web sites requiring a login.

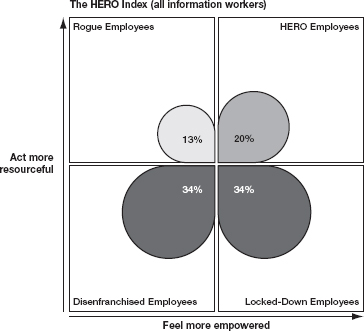

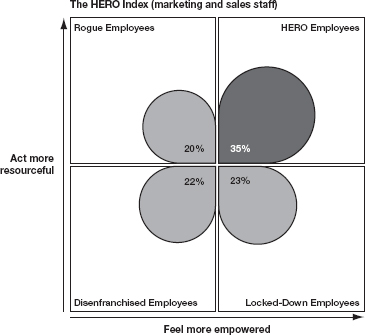

These two dimensions give us a unique view into the capabilities and frustrations of the potential HEROes within companies. Together, they generate four possible states of mind for an information worker within your company (see figure 8-1).

- Disenfranchised Employees are neither empowered nor resourceful. The 34 percent of all information workers in this quadrant don’t use unsanctioned applications and don’t feel empowered to solve problems. They just try to do their jobs. While every company needs some workers who just follow orders, very little innovation is going to come from these ranks.

- Rogue Employees act resourceful, but don’t feel empowered. This quadrant, which includes 14 percent of all information workers, includes people who are running unsanctioned applications even though their company doesn’t support their creative efforts to solve problems. Creative energy is better than complacency, but these unsupported efforts are less likely to contribute to the company’s useful work. If these people are to contribute in a useful way, they need support from their company.

- Locked-Down Employees feel empowered, but don’t act resourceful. This group of information workers is large, at 34 percent. People in this quadrant are pulling along with the company to solve customer problems, but since their technology is locked down by the company, it’s unlikely they’ll come up with technology solutions that will actually benefit those customers. You can’t expect people to paint beautiful pictures if their brushes and paints are locked away most of the time. To get more out of this group, companies need to provide them with technology resources so they can act on their creativity.

FIGURE 8-1

The four types of employees in the workforce HERO Index

Base: U.S. information workers.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

- HERO Employees feel empowered and act resourceful. Here is where technology innovation comes from—the 21 percent of information workers who are using new technologies and know the company wants them to help customers. This is where HEROes come from. All the employee HEROes we’ve met so far—Rachel Nislick at PTC, Rob Sharpe at Black & Decker, Frank Eliason at Comcast, and Marty Collins at Microsoft—came from this quadrant.

If you want to build a HERO-powered business—if you want customer-focused innovations to arise, get supported, and become part of what makes your company succeed—then your job is to create a culture and a set of resources that pull as many of your best thinkers as possible into the HERO employees quadrant.

where do HEROes come from?

We can use these quadrants to analyze any group of workers. And despite their simplicity, they’re highly revealing about where HERO workers come from. We call this analysis the HERO index.

Let’s take a look by industry, for example.

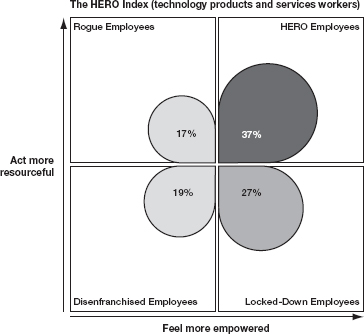

The industry with the highest proportion of HERO Employees among its information workers, 37 percent, is technology products and services (see figure 8-2). While this is extreme, it’s not unique—workers in business services, media and leisure, and financial services all score well above average. Electronics has not just a high proportion of HERO Employees, but also the highest concentration of Rogue employees of any industry. The reasons are clear: technology and electronics are businesses where technology is at the center of innovation, while media and finance are “bit businesses” where companies increasingly compete on their digital delivery (Hulu and E*TRADE are two examples of this). If you’re in one of these businesses, you have plenty of HERO employees and your competitors will, too. You must differentiate on how well you lead and manage them.

FIGURE 8-2

The HERO Index shows that more technology products and services workers feel empowered and act resourceful

Base: U.S. information workers in technology products and services companies.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

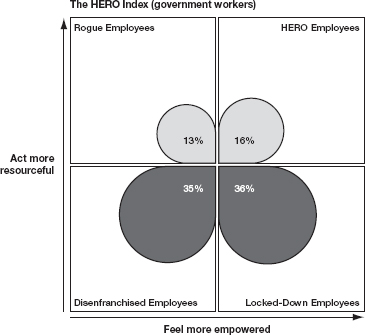

FIGURE 8-3

The HERO Index for government workers

Base: U.S. information workers in government.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

By contrast, retail had the lowest proportion of HERO employees in our survey, 18 percent. While this is dragged down somewhat by all the people in retail sales, it’s a shame, because information workers in retail are exactly the kind of people who would benefit their company by finding new ways to reach out to customers (Best Buy’s Twelpforce, which we described in chapter 1, is a great example). Governments, nonprofits, health care, and education also had few employees in the HERO quadrant, which is why HEROes like U.S. State Department staffer Mark Betka from chapter 2 need to be highlighted; most workers in government either don’t feel empowered or don’t act resourceful (see figure 8-3). In these industries, encouraging HEROes and their innovations can be a significant differentiator against slow-moving competitors.

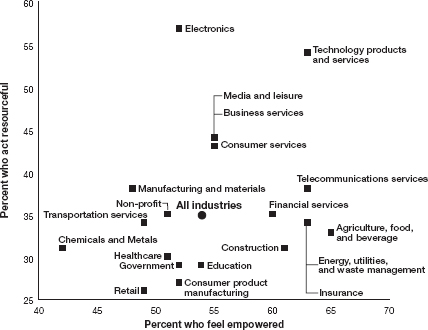

FIGURE 8-4

Different industries show different levels of empowerment and resourcefulness

Base: US information workers.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

One other industry is worth examining here: the telecommunications business. Telecom is about average on HERO employees, but 41 percent of its information workers are in the “Locked-Down” segment—employees who feel empowered but don’t act resourceful. Innovation in telecom would benefit from managers who encourage more experimentation with technology among their employees, though with safeguards in place to protect against service failures. Given how central new technology services and products will be to telecom, and the rapid rate of evolution of mobile technology, this could make all the difference in a telecom company’s future competitiveness.

FIGURE 8-5

Marketing and sales staff are likely to be in the HERO quadrant

Base: U.S. information workers in marketing and sales, excluding retail sales.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

If you want to compare your industry to the rest of the working world, have a look at the grid comparing all the information workers in our survey by industry (see figure 8-4).

What departments in your organization include the most HEROes? Based on our survey, marketing and nonretail sales have the highest proportion of empowered staff (see figure 8-5). Since it takes an empowered employee to serve an empowered customer, this makes sense. It also means that if your marketing and sales staff don’t feel empowered, your competitors are probably innovating more than you do. Customer service, on the other hand, is near the bottom, with less than one in five employees in the HERO quadrant. The appropriate visual is a hive of call center workers, stuck in cubicles, unable to contribute meaningfully to the company’s ability to innovate in groundswell customer service. (In other words, the opposite of Zappos.)

Unfortunately, even as these service people learn more every day about what’s bothering customers, they’re mostly unable to use that knowledge to suggest innovations that might solve those customers’ problems. What a waste, given the word of mouth that happier customers could create.

two ways to improve your company’s culture and readiness

The HERO index is more than an assessment of your company’s readiness. It also tells you what to do to create and encourage more HEROes and more innovation and build a HERO-powered business. To get more people into the innovative upper-right quadrant, you can make improvements in two directions: changing your culture to make people feel more empowered, and adding resources (or providing permission to use those resources) to help people act more resourceful.

- To help more workers feel empowered, improve leadership and management. HEROes want to create solutions. Companies want people pulling in the same direction, not chaos. This creates tension. The solution is to align your management and culture with HEROes. The PTC case is a great example of what HEROes can do when they’re aligned with management—and also of how this process can take a while.

- To help more workers act resourceful, support them with technology. HEROes need help. They need access to technology, not locked-down systems. They need tools to help them collaborate, support from technology professionals, guardrails to keep their solutions safe, and systems that spread their success across the organization. For a great example of how this works, take a look at how the IT department at Sunbelt Rentals used iPhones to create sales HEROes.

CASE STUDY

Sunbelt Rentals empowers its workers with mobile decision making

Sunbelt Rentals is filled with employees who feel empowered. They really want to help customers. But it took John Stadick a few tries to figure out the resources they needed.

Sunbelt rents stuff that construction workers use. Its business depends on the sales guys. The company generates over a billion dollars’ worth of construction equipment rentals every year, from huge backhoes to handheld drills, and it all comes down to a salesman talking to a construction manager.

A sales guy (it’s nearly always a guy) drives his truck up to a construction site. The construction manager says something like, “I’m going to need two jackhammers tomorrow” or “How much for a high-capacity water pump?” Now the sales guy has to figure out if the equipment is available, and what it should cost. Until recently, that meant checking a price sheet printed out on Monday that might be out of date by Thursday. Or he could call somebody at the branch office on a Nextel phone and hope she got back to him in time to close the sale—before the rep from the competing rental company showed up, that is. A lot of the quotes were seat-of-the-pants, based on what somebody got charged last time. The customers were happy and the sales guys were doing their jobs, but things weren’t running efficiently.

John Stadick, the vice president of information technology for Sunbelt, knew this was an information problem. He knew what construction was like; he had worked construction sites while in college. And he had the information the sales force needed in a database he’d built. “We knew we had to find a better way of empowering those guys,” John said. “What’s the status, what’s the price? We had to empower the sales guys to find the piece of information themselves.”

His problem wasn’t a failure to provide resources. He had tried giving them BlackBerry phones with inventory applications on them. The sales guys wouldn’t use them. It was “too hard to find what they needed.”

How about laptops with wireless data through a mobile phone network? That didn’t work, either. The laptops couldn’t handle the grit of a construction site, and they fell off the seats and broke a lot.

Was the sales force just resistant to technology? John didn’t think that was the problem. They were problem solvers, after all. But like their customers, they needed the right tools for the job.

Finally, Dean Moore, a senior systems engineer working for John, suggested iPhones. This was a promising idea—the phones connected and made information available quickly, with the kind of interface that sales guys could master. So John, Dean, and a developer built an app that could show inventory and pricing. It took about four months to connect the iPhones to John’s database. They rolled the phones and apps out to twenty-five local reps, encased in hard-shell “Otter Boxes” that kept the phones safe on job sites. “We built in some tracking tools so we could see what features were being used,” John says. “The usage statistics were off the charts.” Finally, John had found a solution that would enable the sales force to act resourceful. He expanded the pilot and began to measure the results.

Phone calls to the branch offices were down 30 percent. But more importantly, rental rates were up—up 3.5 percent versus a control group that didn’t have the iPhones. Because the sales guys no longer quoted from the hip, they were giving accurate rates from the database. Every dollar of that increase went directly to the bottom line. It also helped that they could remind a customer of equipment already rented and, when appropriate, bills that hadn’t been paid yet. John rolled out the iPhones to the rest of the sales force.

John figured out how to get his sales force the resources they needed. Now he’s got six hundred more resourceful problem solvers coming up with new ideas on how to make his company successful.

how management and IT can support HEROes

In the previous chapter, we talked about the HERO Compact among managers, IT, and HEROes. The tools in this chapter show how to assess your company’s readiness to become a HERO-powered business. Next, we want to provide some practical advice on what managers and IT can do to make this new way of doing business a reality.

Leading HEROes is hard. While you have to give up central control of technology, you must also lead your HEROes so they end up contributing to your business. We tackle this essential contradiction in the next chapter.