7. do-it-yourself technology fuels the HERO Compact

HEROes pick their own technologies. They also make mistakes.

Take Gary Koelling and Steve Bendt, two Best Buy advertising staffers who launched Blue Shirt Nation, an internal social network for the company’s “blue shirt” retail sales staff. Here’s how we told the story in Groundswell:1

Gary started in August 2006 by finding a spare server, stashing it under his desk, and loading it with Drupal, an open-source suite of community-building software … The project took off when they showed it to the senior VP of marketing, Barry Judge, who told them that they weren’t thinking big enough—and promptly offered them a generous budget to build out the community.

When we reconnected with Gary and Steve in 2009, we were surprised to learn that after a lot of initial success, Blue Shirt Nation was about to shut down. What happened? As it turned out, for Best Buy, Drupal was not the right platform for the long run.

Gary told us, “Drupal gets you 80 percent of the way there, really fast.” But as Steve points out, they had to give up on Blue Shirt Nation because the platform needed to reach managers, not just blue shirts, and managers had different needs. “Employees could upload video and pictures. They could create groups … But one problem we ran into was the adoption of top management, like general managers [of stores]. They didn’t have the time to sit down at a Web portal every day … ‘How do we work? Well, we work with [Microsoft] Outlook, we work with our phones.’ We needed a platform that could plug into those channels.”2

Since managers were insisting on it, the platform would have to work with BlackBerry phones, text messaging, and corporate email. Best Buy’s corporate group, working with IT, rolled out wikis and discussion forums on Microsoft SharePoint that could meet these requirements. Combined with some custom software, the result was very popular. When the time came to shut down Blue Shirt Nation, most of the activity had already migrated to the more robust systems.

You could easily draw the lesson from this that allowing marketing people or other nontechnology staff to provision—that is, acquire and install—their own technology is a mistake. Gary put a server under his desk with Drupal, and it didn’t do the job. Isn’t that proof that HEROes deploying technology just create problems?

But before you accept that conclusion, look at what Blue Shirt Nation brought to Best Buy. “Before Blue Shirt Nation, there was a lot of mistrust between corporate and the field,” Steve says. And as Gary told us, “It led to a big cultural change. Answers used to come from corporate. Now there is more and more focus on retail and store employees as the place where the answers come from, and where people have tools to make a difference.”

Out of Blue Shirt Nation came change. It spawned Twelpforce, which empowered staff to help with Twitter support, as you read in chapter 1. Barry Judge learned to embrace ideas not just from his staff, but from customers. And the new system, the better system—the one that managers can use with Outlook and their phones—would never have been created were it not for Blue Shirt Nation. Blue Shirt Nation, a system created by a couple of guys in the advertising department, showed Best Buy what was possible and how to embrace the HEROes in its workforce.

So calling Blue Shirt Nation a technology mistake misses the point. HEROes don’t operate at the speed of IT, they move at the speed of the groundswell—and as a result, they need to provision their own technology. That’s how cultural change starts. And should they experience success, like Blue Shirt Nation did, the IT department needs to help them move from what they’ve built to a system that the company can run on.

the HERO Compact: IT, managers, and HEROes

The story of Blue Shirt Nation highlights a fundamental challenge for the HERO-powered business. While HEROes are a force for innovation and they serve empowered customers at Internet speed, they also make mistakes, especially when it comes to technology choices. Often those mistakes leave a mess. The IT department and their managers end up cleaning up those messes. This can lead to a desire to lock things down, shut things down, and keep things safe. Unfortunately, those very impulses also crimp HEROes and slow innovation.

What’s a company to do?

In examining hundreds of cases of HERO-driven innovations, we’ve learned a lot about organizational behavior. We’ve seen companies like Best Buy, the Philadelphia Eagles, and Intuit where the IT groups, managers, and HEROes have come to a détente; where they’ve worked out ways to support each other and keep the company thriving while keeping systems safe. We’ve seen many, many more cases where companies lock down systems, say no to HEROes, and make innovation difficult. HEROes at these companies become discouraged or may give up and quit, leaving the companies unable to respond in the face of empowered customers.

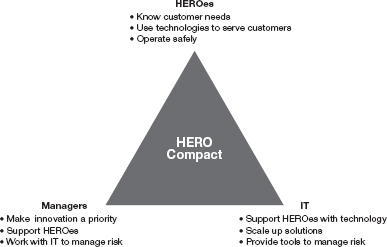

In a HERO-powered business, empowered employees are a continuous force for innovation in service of customers. But it takes three groups working together to make this customer-focused innovation possible and safe: IT, managers, and the HEROes themselves (see figure 7-1).

It’s not easy for them all to get along. When they do, it’s because they each understand what they’re uniquely responsible for and how they work together. We call this new way of thinking the HERO Compact (see box).

FIGURE 7-1

The HERO Compact is at the center of the HERO-powered business

the HERO Compact

In a company that supports customer-focused innovation, managers, IT, and HEROes must work together differently.

- IT is responsible for supporting HEROes with technology innovation, giving leaders the tools to manage risk, and scaling up successful solutions.

- Managers are responsible for making customer-focused innovation a priority, establishing the governance structures to support HEROes, and working with IT to manage the business risk of technology.

- HEROes are responsible for knowing what customers need, experimenting with technologies that solve customer problems, and operating within the safety principles established by IT and managers.

In retrospect, you can see that the successful companies and projects we described in the first half of this book adopted this compact. In the rest of the book, we will formalize this: we will show exactly what a company needs to do—in IT, in management, and with its employees—to make HERO-powered innovation successful.

IT’s role in the HERO Compact

Let’s start with IT departments and their responsibilities for technology. In the past, IT mostly had two jobs. The first was to build and support big technology projects—corporate databases, core business applications like accounting systems, network infrastructure, servers, and PCs for the information workers in companies. The second was to make sure any systems that these workers used were safe and that they kept data secure and functioned properly.

HEROes threaten both of these jobs.

HEROes are do-it-yourselfers. They pick technologies that often aren’t sanctioned by corporate IT. Why is this happening?

For one thing, they are exposed as consumers to powerful mobile, video, cloud, and social technologies. They see Facebook and ask, “Why can’t we do an employee social network?” They make videos of their kids and say, “I could make training videos.” They collaborate in their spare time with fellow volunteers on Google Docs and wonder if their company could use them. Because most of these tools are free or cheap and easy to use, many of your information workers are mastering them right now. We call this trend “technology populism.”3 Researchers at Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) have called it the “consumerization of information technology.”4 But whatever you call it, it means that new technologies are creeping into every workplace. Even if the PCs are locked down, personal mobile devices that browse the Web aren’t—so people end up using their own technologies at work all the time.

The second reason that HEROes use do-it yourself technology solutions is that they live with empowered customers. Whether they’re in marketing, sales, or customer support, they are typically directly in touch with customers and their problems and desires. It’s just too tempting to solve the problems right then and there with technologies that are readily accessible. Whether it’s an account manager prospecting on LinkedIn or Gary Koelling putting a server under his desk, technology solutions, created by HEROes, spread throughout the organization.

What should an IT department do? They can’t run these projects; they are too small and there are too many of them. They can’t outlaw all of them either—that’s cutting off a huge source of customer-focused innovation. But for an IT professional, employees using do-it-yourself technology feels like a virus invading the body—it’s alien. IT’s natural reaction is to say no, or at least whoa. After all, it is the CIO and IT group’s responsibility to scale and secure the technology the company runs on and stay on the right side of the law. If they don’t have a part in selecting and deploying the tool, they get very nervous.

IT needs to take on a new role, as a key advisor to HEROes and their managers, a role we will describe in detail in chapters 12 and 13.

First of all, it’s IT’s job to help HEROes pick the right technologies. In the Best Buy example at the start of this chapter, IT helped make the transition to the right platform for Best Buy’s internal sharing software. In the next chapter, you’re going to see how the CIO at PTC, a software company, helped marketing staffers pick the right platform for an online community. More and more, supporting technology innovation as a trusted counselor will become the IT manager’s role.

IT also must help manage technology risk. Take iPhones. One IT manager at a global insurance company described it to us this way. “I know I’m going to have to support the iPhone. Everybody is asking for it. Even my CEO wants to know when I’m going to let him use his iPhone. But my problem with iPhone right now [in April 2009] is that I can’t yet stand up in front of a judge and explain how it meets our compliance requirements. And that’s part of my job.” While IT cannot eliminate risk, it is the IT group’s role to assess and mitigate risks that come from HERO projects.

IT must also scale up the HERO solutions that work. This is where IT’s traditional role intersects HERO initiatives most directly.

Finally, IT must be involved with corporate systems designed to improve employee innovation and collaboration, the systems we will describe in chapters 10 and 11.

IT’s pledge in the HERO Compact

- I will focus more on customer-facing opportunities in addition to systems, risks, and operations.

- I will respect requests for new technology support and find ways to say, “Yes, and” rather than automatically saying, “No.”

- I will explain the reasons for locking down new technologies and immediately begin looking for ways to unlock them. I will reexamine decisions to lock down new technologies at least once a year.

- I will focus on technology innovation as a core skill so I can counsel HEROes when they come with technology ideas.

- I will question the default assumption that people using do-it-yourself technology are creating risks or wasting time.

- As new HERO projects get off the ground, I will seek ways to help HEROes and their managers scale them up successfully and keep them safe.

- I will focus on training people about risks at least as much as on implementing lock-down technology solutions.

- I will help with the development of corporate systems to promote innovation and collaboration.

In the new world, IT is a driver, protector, and supporter of HERO-powered technology projects. This requires a change in mind-set. We’ve assembled the elements of this change into a short document called “IT’s Pledge in the HERO Compact” (see box).

management’s role in the HERO Compact

Just as IT needs to redefine its role, so must managers. For a company to become a HERO-powered business, managers must change their mind-sets as well.

Senior leaders must focus on encouraging innovation. But to prevent chaos, that innovation can’t be random; it must align with corporate strategy. In a company that wants more innovation, leadership has to communicate its goals and strategies more effectively or there will be a lot of wasted innovation. To encourage innovation, management needs to support HERO efforts not just with lip service, but with its behavior, by focusing on learning from mistakes rather than on punishing mistakes.

An emblematic example comes from Jeff Bezos at Amazon.com. Jason Kilar, currently CEO of Hulu, used to run Amazon’s DVD business. He once ran an experiment in which half the people who looked at DVDs got one price, and half got a lower price. It blew up into a huge embarrassment, with people making accusations that the company was discriminating. As he told Wired magazine:5

I emailed Jeff Bezos as soon as I found out. He summoned me to a conference room. It was definitely not an enjoyable walk down there. I’d been at Amazon for only three years, and I didn’t have the luxury of a ton of experience to fall back on. But once I got into that room, the tone was exactly the opposite of what I expected. All Jeff wanted to know was what had happened and what was the best thing we could do at that point. The next morning he appeared on the CBS Early Show and explained everything. It was a defining moment for me.

That’s how senior leaders encouraging innovation behave. What about the other managers in these companies?

The manager of a HERO is in a crucial position. Often HEROes don’t have all the political skills necessary to take a project from idea through to completion, and they need help from their managers to deal with other affected departments, including IT. HEROes may also lack the perspective to understand whether their idea will actually help customers or not, while managers can often see this more clearly. As a result, managers become key allies as HEROes’ innovations go from ideas to actual projects.

Like IT, managers have a role in the HERO Compact. Their responsibilities are focused around tolerance of experiments and ways to support projects appropriately, as we describe in “Management’s Pledge in the HERO Compact” (see box).

management’s pledge in the HERO compact

- I will articulate and continually communicate the customer goals of the organization and of my department, so that each employee can understand them and pass them along to others.

- I will provide the governance and policy to help HEROes come up with creative solutions that are in line with our goals.

- I will encourage experimentation to solve customer problems where needed.

- I will expect mistakes and failures. I will seek learning from those mistakes and failures, rather than focusing on punishment.

- When HEROes come to me for help, I will seek ways to support their projects by carefully evaluating them and working with other managers to solve the challenges they create.

- I will respect assessments of technology risk in HERO projects and work with IT and others to quantify, mitigate, and ultimately manage that risk.

the HERO’s role in the HERO Compact

We’ve talked a lot about HEROes in this book so far. But HEROes don’t work alone; they need to function as part of a corporation. And they need IT’s help. In chapter 2, we talked about how Rob Sharpe at Black & Decker needed a video server and IT support to provide the video library that his sales training needed. And Ross Inglis at Thomson Reuters needed serious support and development help from IT to build the independent financial advisor portal. The bigger the project, the more it grows beyond what a HERO can do alone.

It’s a two-way street. Even as IT and managers need to respect the HERO’s need to experiment with new technologies to solve customer problems, HEROes need to respect IT’s and managers’ priorities. HEROes can succeed only if they work within the boundaries set up by the company—perhaps near the edges of those boundaries, but not beyond.

What can managers and IT groups expect in the way of appropriate behavior from HEROes? To begin with, HEROes must prove that their projects serve customers. They must work with managers and IT to make sure those projects are safe. They also have a responsibility to other HEROes to spread what they learn, just as Gary Koelling and Steve Bendt spread their knowledge to kick off a whole slew of new projects at Best Buy. The HERO’s mind-set complements the mind-sets of IT and management, as we describe in “The HERO’s Pledge in the HERO Compact” (see box).

do-it-yourself technology in the workplace

The first and most obvious place that HEROes, managers, and IT come into conflict is on corporate PCs and smartphones. What sorts of technologies should employees be able to use in their workplaces? Is it acceptable to use devices, applications, and Web sites that aren’t sanctioned by the company?

Let’s analyze this from the perspective of the three groups in the HERO Compact.

IT people have a strong incentive to block application downloads, block access to many types of Web sites (including social networks), and stop mobile devices from connecting to corporate systems. People could be downloading viruses. They could create desktop configurations that IT can’t support, and that interfere with corporate applications. Their applications use up corporate bandwidth. It’s simplest just to ban these activities.

Managers, too, may decide that their workers will be wasting time and productivity on these activities. Why not just stop people from playing around when they should be working?

The problem, from the HERO’s point of view, is that many of the best customer-facing ideas require using these online resources and accessing these sites. Would Gary Koelling and Steve Bendt have come up with the idea for Blue Shirt Nation if they hadn’t used Facebook? As Irving Wladawsky-Berger, the strategy executive who helped revitalize IBM, puts it, “If you are in an organization where people don’t participate in the social media discussion both externally and internally, it slows everything down.” HEROes need access to these resources. It’s awfully hard to develop projects around tools like social networks, video, and mobile devices if you can’t even use them at work!

the HERO’s pledge in the HERO Compact

- I will respect the influence of empowered consumers.

- I will explore technologies that can help solve customer problems.

- If my projects entail a significant effort, I will work with my managers and IT to better understand the long-term impact of those projects.

- Where a project creates a risk, I will work with IT and management to understand that risk, assess it, and when possible, mitigate it.

- I will seek ways to take lessons from projects and spread them throughout the organization.

- I will work with other HEROes in innovation and collaboration systems, if the company has those systems.

- When I have access to do-it-yourself technologies, I will use them to advance the business, not for personal or recreational purposes.

Both sides of this argument have justification. Here’s where we come down: companies should block as little as possible, but IT, managers, and employees should work together to manage risk and explore alternatives to find an acceptable solution. That’s the HERO Compact. To help support those decisions, let’s take a look at just how prevalent unsanctioned access is, and what the consequences of locking down technology would be.

how prevalent is do-it-yourself technology in the workplace?

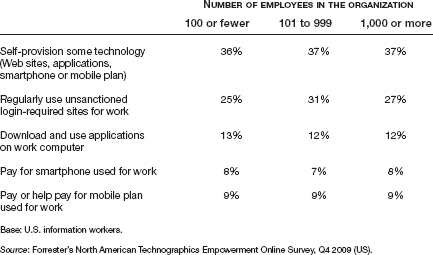

In the same online survey we used to examine the behavior of people as consumers, we asked people to tell us about their use of technology at work. Of the slightly more than ten thousand people in our survey, 4,364 were information workers—people who work with a computer. This group includes administrative staff, call center workers, and even some shop floor staff and cashiers along with traditional office workers.

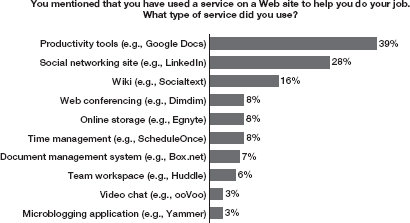

More than one in three of the information workers in our survey used some form of do-it-yourself technology for work (see table 7-1). More than 10 percent used smartphones, and of those, the majority had provided the phone themselves. About one in seven information workers were downloading applications to work computers. But the biggest self-provisioned technology is Web sites that employees use that aren’t sanctioned by IT. The most popular sites among information workers in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom were sites with productivity tools like Google Docs and social networking sites like LinkedIn (see figure 7-2).

TABLE 7-1

Many information workers use do-it-yourself technology

FIGURE 7-2

Web sites and services that information workers use

Base: 947 U.S., Canadian, and U.K. information workers who have used a service found on a Web site to help do their job (multiple responses accepted).

Source: Forrester’s Workforce Technographics US, Canada, UK Benchmark Survey, Q3 2009.

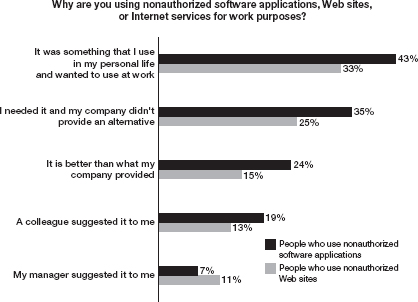

Why do workers use do-it-yourself technology? The most common reasons are that they are exposed to it at home, as a consumer, or that they need it and the company doesn’t provide it (see figure 7-3). Many feel they have better technology at home than they do at work.

But if you really want to know what’s driving this behavior, just listen to the people who are doing it. Here are some of the reasons the people in our survey gave for using do-it-yourself technology in their jobs:

Because it is easier and faster than what is provided at work. And it gives better results.

Getting the job done requires multiple resources and to do my job to the best of my abilities I use all available resources.

The ones they prefer are slower, less organized, and hinder my performance, causing me to take longer to do simple tasks.

I am a physician and there are several sites that augment what is available for me through my employer. Having access to these sites improves my ability to provide for my patients.

FIGURE 7-3

Employees use do-it-yourself technology because it solves problems

Base: U.S. information workers who use nonauthorized Web sites or software applications (multiple responses accepted).

Source: Forrester’s Workforce Technographics US, Canada, UK Benchmark Survey, Q3 2009.

My software needs advance faster than the company’s process of testing, setting policies, and distributing software.

I use Google Docs most of all because: 1) the storage is practically unlimited and can be accessed from any computer; 2) it is always up to date with the latest version; and 3) I don’t have to worry about a computer crash.

LinkedIn is a great way of keeping track of clients when we are trying to drum up new business.

The software and applications I use are integral for accomplishing my job. The IT geeks are idiots and will not allow anything other than [their] approved programs.

I access my personal e-mail and the Facebook application at work because sometimes my clients contact me through them.

These are people trying to do their jobs better. But in many cases, the company is determined to stop them. In another survey we found that most information workers had sites blocked by their employers: 68 percent in the United States, 69 percent in Canada, and 79 percent in the United Kingdom. For every worker who’s trying to do the job better with her own tools, even more are trying to obey the company’s rules. Their reasons are much more consistent—you can hear the fear talking:

I can’t download anything without an administrative password. Not even updates on authorized software. It’s a pain!

At my company, our server has most unauthorized sites blocked and we are not authorized to add new software on our computers. I couldn’t do these things even if I wanted to.

I don’t want to get in trouble. I have signed many user agreements in which I said I would not.

Because the IT guy in charge of the central computer would have a fit, that’s why.

Because you will get FIRED!!!!

assessing the risks and benefits of do-it-yourself technology

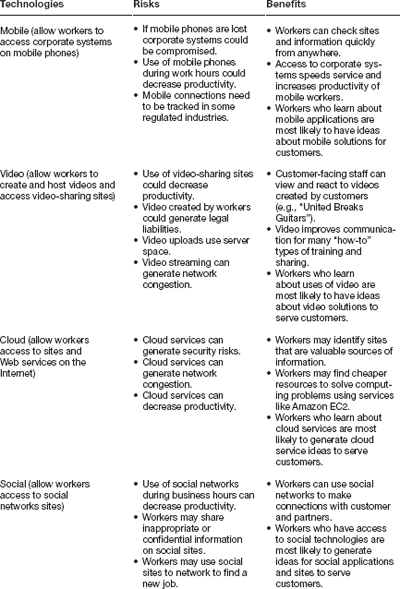

According to the HERO Compact, we should carefully analyze a problem like people using unsanctioned devices, applications, and sites in the workplace instead of just rejecting it out of it hand. What are the risks and benefits?

We’ve already described the risks, which center mostly around security and productivity. But you might be surprised about some of the benefits.

For example, we heard this story from an IT executive in a multinational construction firm in 2010. The company had just implemented a snazzy new telephone and Web conferencing system. Once this rolled out, the IT security group took the opportunity to do something it had been hoping to do for a long time—it blocked people on its corporate networks from using Skype, the Internet telephone software, and thereby hoped to reduce network congestion and improve security. What happened next surprised everybody—a stream of profane calls and emails from some extremely upset employees. Were these people annoyed they couldn’t call their friends on vacation in Tahiti? No, as it turned out, the company’s customers in Pakistan and Vietnam were completely dependent on Skype for telephone communication, and the company had just cut them off. (In the end the company relented and restored access to Skype.)

IT and management at your company need to create a chart like table 7-2 to decide what sites and behaviors need to be blocked. But you might need to think a little broadly about the benefits, and figure out if there is the equivalent of a free, necessary technology like Skype in use at your own company.

Finally, consider this. Blocking every possible dangerous site is pretty much impossible, especially when people are using mobile phone browsers, not just corporate PCs. You’re probably better off keeping an eye on this technology and how people use it, rather than trying to squash it. The more you block, the more you send the message “We don’t trust you with new technologies.” It’s hard to get people to innovate when this is what they’re hearing.

putting the HERO Compact into action

As IT, managers, and HEROes begin this journey toward the HERO-powered business, they need a map. That’s what we provide in the rest of this book.

Chapters 8 and 9 are focused on management and culture. Managers need to know how ready their companies are for HERO-powered innovation—we provide tools for assessing and changing that in chapter 8. Chapter 9 is about leadership and governance—how to run a HERO-powered business without creating chaos.

Chapters 10 and 11 describe systems for HEROes. We talk about both systems that help drive innovation (in chapter 10) and systems that help HEROes to collaborate (in chapter 11). These management tools for the HERO-powered business are often created and run by IT for the benefit of the company. They can make a huge difference, but they often fail; we’ll describe how to make them successful.

TABLE 7-2

Benefits and risks of employee access to do-it-yourself technology

Chapters 12 and 13 focus specifically on what IT can do in its new roles driving, supporting, and safeguarding HEROes. If you’re an IT professional, chapter 12 tells you how and when to say no, and how to set up principles to keep HEROes safe, while chapter 13 tells you how and when to say yes and support HEROes as they innovate.

We bring it all together in chapter 14, which discusses the new mind-set everybody needs in the world of HERO-powered business.