[ 2 ]

EXTRACTING INSIGHT FROM EXPERIENCE

To be thrown upon one’s own resources is to be cast into the very lap of fortune; for our faculties then undergo a development and display an energy of which they were previously unsusceptible.

—Benjamin Franklin

PEOPLE WHO UNDERGO A CRUCIBLE and grow through the experience all share something vital: they don’t become stuck. No matter how much they struggle, no matter how much they may grieve, and no matter how much they may chafe at finding themselves in situations they cannot immediately control, they are not paralyzed by difficult situations. Where others see chaos and confusion, they see opportunities to learn and grow.

This chapter explores the role of crucibles in the education of a leader and begins to examine the first of the four major findings from my recent research—specifically, that crucibles contain two valuable lessons, not just one: lessons in leadership and lessons in learning. Here we search for answers to core questions about how leaders learn, like What is life like inside a crucible? How do people make sense of their crucibles, much less learn from them? And perhaps most importantly, Can anyone harness the power of experience—or is that a reward reserved for a favored few?

I have already defined a crucible as a transformative experience through which an individual comes to a new or an altered sense of identity. But look closely at the crucible experience, and you will see distinctive contours and trajectories. Crucibles invariably rupture the status quo. Sometimes they sever a comfortable web of relationships, as in the case of war, insurrection, or terrorist attack. Sometimes they change a person’s expectations dramatically and unpredictably, such as when a policeman is thrust into the role of wartime commander or when a consummate insider is expelled by her comrades. Other crucibles challenge an individual’s identity, like the wrenching episodes of self-doubt occasioned by bankruptcy, loss of an election, or the death of a loved one. People experience crucibles most commonly as a profound tension or conflict between opposing forces.

Despite their differences, a powerful unifying theme emerges from close study of the variety of crucible stories: crucibles catalyze the process of learning from experience. Consider, for example, the following story from Major Joe Rupp, U.S. Marine Corps and a commander in Desert Storm.

Early in his career, Rupp took leave from the military to fulfill his missionary obligation to the Mormon church—where he would learn things about leading that he’d overlooked in officer candidate school (OCS). Assigned to a village in Mexico, he and a companion were making their rounds, meeting church members on a particularly hot day. “This was really unfamiliar territory to me,” he recalled. “Despite having been through boot camp and OCS, I was basically still this kid from Utah.” So when a village woman offered the young men some refreshing papaya water, they eagerly accepted. “She chopped that papaya up and threw it in a bucket of water and threw some sugar in there and gave it to us,” Rupp said. “And I drank three glasses. I was thirsty and didn’t want to offend anyone.”

His politeness cost him dearly. He got a case of dysentery that made him drop twenty pounds within a week. He was so sick that at one point he asked his zone leader whether he could call his mother. “I’d been a Marine. I was strong,” he recalled. “I knew all about going on a mission. And there I am in front of my zone leader crying. All I want to do is just call my mom because I feel absolutely miserable. But he said, ‘No. I’m not going to let you call your mom. That’s not why you’re here. You didn’t come here so you can get sick and feel sorry for yourself and call your mom. When Christ was here on earth, he suffered the same things that the people on earth suffered. And these type of infirmities are what these people down here deal with every day. This isn’t about you. It’s about them.’”

Rupp said his leader’s words had such an effect on him that he wrote them down. “That situation taught me a great lesson: that I should not be so focused on myself and look at situations only as how they affect me.”

While in OCS, Rupp had been advised repeatedly to put his people ahead of his own needs (and to avoid untreated water), but those lessons never really took root. That bout of dysentery put his view of himself into stark relief—in a way that classroom instruction and even Marine training couldn’t. He “mattered,” as he was reminded by his zone leader, but not in the way Rupp had thought: not at the center of the situation, but as a part of the situation. A mild rebuke, perhaps, and certainly not an earth-shattering experience, but it forced Rupp to both recognize and resolve a tension between his vision of himself and his role and the expectations that others had of him.

Later, as a helicopter pilot and commander in Desert Storm, he recalled his experience in that little Mexican town and counseled his peers as well as his direct reports about the importance of attending to the needs of the local population before grousing about the heat, dust, and sand. It is also important to note that Rupp, like many leaders we studied, did not go through his crucible alone. The lessons he learned were intensely personal, but in his case (and others I’ll explore later), a teacher, a guide, a mentor, or a coach played an essential role in helping him sharpen his focus, to see what truly mattered in the situation he faced.

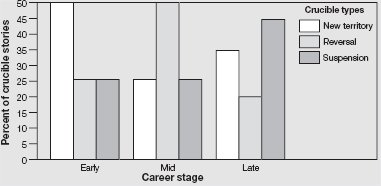

Crucible experiences like Rupp’s teach something deep and enduring about how to behave (or how not to) in the face of real impairment and demoralization. In fact, my analysis of nearly two hundred crucible experiences pointed to three major types, each with its own unique signature. (See the box, “Crucibles in a Career Perspective.”) Some involve encounters with the new or unknown, which I refer to as new territory. These crucibles sharpen an individual’s alertness to new information and his or her skill at sense making in the midst of confusion. A second type of crucible involves loss, impairment, defeat, or failure of the kind that Rupp faced; I refer to this as reversal. Reversal teaches both endurance and imagination. Finally, there are the crucibles that involve an extended period of contemplation or deliberation, which I refer to as suspension. Suspension challenges a leader to clarify his or her values and purpose in life.

All three types of crucible test an individual’s adaptive capacity and resilience in the face of trying circumstances. Each crucible represents a different kind of problem, but what they share in common is a fundamental tension. Like a stretched rubber band, a crucible embodies potential energy—energy that can be released productively or unproductively. In the following sections, we’ll consider examples of each type of crucible, first in the context of lessons they have to teach about leadership and then through the lens of lessons that each type has to teach about learning.

LESSONS ABOUT LEADERSHIP

Crucibles teach powerful leadership lessons. Repeatedly, the lessons people extract from their times of trial became touchstones they carry with them for the rest of their lives. Crucible stories are, in many respects, the raw material from which outstanding leaders derive their core qualities—that is, these are lessons about adapting and growing, about discovering new ways to engage or enroll others in a shared pursuit, and about recognizing the right thing to do and summoning the courage to do it.

Let’s begin by looking at the kinds of leadership lessons that crucible experiences in new territory can foster.

New Territory

Being thrust into a new terrain—an overseas assignment, an unexpected turn of events in business or family life, a new social or organizational role—carries with it a challenge not simply to survive but also to prosper in unfamiliar soil. The challenge is to overcome the disorientation and weave it into one’s own experiential tapestry, rather than being consumed in the newness, confusion, and deluge of foreign sensations. For many of the leaders with whom we spoke, the crucible was a dividing line that, once crossed, forever heightened their alertness to the power of experience.

Consider the example of Patrick Mellon (not his real name), an executive highly regarded for his track record as a leader of corporate turnarounds. Over the course of nearly three decades and in a dozen companies, he has earned a reputation as a toughas-nails negotiator who can stare down creditors, soothe anxious investors, and rally the spirits and the energies of employees and pensioners with the greatest personal stakes to lose.

When asked about a time in his life in which he learned something important about leadership, Mellon paused and took a breath before describing an event that occurred when he was a teenager pledging membership in a high school honor society. “They dropped me in the woods in what had to be the darkest, the most isolated corner of this huge forest,” he began, “and they made me swear on my mother’s grave to not remove the blindfold until I could no longer hear them. This was part of the test. If I could find my way back to camp, I’d be accepted into the society.” When Mellon finally removed the blindfold, he found himself in complete darkness, in a place so pitch-black that he couldn’t see the hand in front of his face. “I didn’t dare move because I couldn’t tell if I was on the edge of a cliff or at the bottom of a pit,” he recalled.

That’s when it hit him: he was utterly alone, in a way he’d never been before in his fifteen years. “I started to shiver and panic,” he said. “I moaned out loud. I broke down and cried. It’s embarrassing to tell you this. Gone completely was the Eagle Scout who had all these merit badges. I was totally, completely panicked and sure that I would never find my way back to camp, that I would be lost there, fall off a cliff, break my leg … or worse, that they would have to mount a search and it would be on TV and I would be embarrassed beyond belief.”

After about two hours, Mellon recalled, he finally calmed down. “It was like one half of me—the rational half—had to talk the other, irrational half through a crisis. I’d never had to calm myself like that before.” That night he learned two important things about himself, he said: that he is capable of panic—and of leading himself out of panic.

Still, the fact that he’s capable of panic is why he preferred to use a pseudonym for his interview: for fear that his direct reports might lose confidence in him. Today when he starts to feel panic coming on, he said he stops and takes a few deep breaths. “And I recall what I learned when I was 15. I walk myself mentally back through situations where I’ve faced that kind of stress and uncertainty before. And I recall what I did to sort things out, how I behaved, how I enlisted other people to help me, and how we created a solution where it didn’t look like one was possible.”

Given that Mellon was in the midst of a difficult turnaround assignment at the time of our interview, his choice of crucibles to relate was probably not coincidental. But in that story, he revealed how he had transformed his own sense of weakness and shame—a profound tension between the way he’d always thought about himself and the young man immobilized by fear in that dark corner of a forest—into a strategy for managing himself and others around him in times of distress bordering on panic.

But what real impact did Mellon’s experience have on his later behavior as a leader? He said, “It made me a more compassionate leader. Up until that time, I’d never met a challenge I couldn’t take on and beat. But here was a situation where the stakes turned out to be much, much higher than I’d ever faced before. I just suddenly realized that this was real—not an exercise, not a classroom test, not me scampering down a rock wall with a belay rope there to save my ass if I did something stupid. There was no walking away.” He understood for the first time what it meant to be faceto-face with forces he couldn’t control. As a leader today, Mellon said, that experience as a teenager later helped him understand how people, from executives to blue-collar workers, feel when higher-ups make a radical change that affects their lives.

“I realized something about the panic that other people must feel when things just suddenly fall apart—like losing your job or seeing your pension evaporate. I learned that panic can be real, that I could experience it, and that fortunately I could also work my way out of it. And so could other people,” Mellon said. “It’s a truth I’ve tried to pass along to the people I mentor.”

His memory of that crucible—and the way he resolved the tension and he drew himself out of it—have enabled him to cope with the vexing, contentious, and worrisome situations that beset an organization or a community in crisis, situations he faced dozens of times over the years. Indeed, that night in the woods alerted him to the learning opportunities that are so often deeply embedded in crisis.

Another leader whose crucible experience involved new territory was Ling Yun Shao, a sergeant in the U.S. Army Reserve. Shao, named by a leading women’s magazine as one of the top ten women leaders in U.S. colleges, initially applied for an ROTC scholarship in order to pay for college. However, after a year of what she dismissed as “simulated soldiering,” she enlisted in the regular army and went through basic training. As it was for the millions of men and women who preceded her, boot camp was an eye-opener for Shao. Even though she learned a great deal about American diversity (having grown up in a fairly sheltered suburban environment after her parents emigrated from China), the leadership crucible she nominated as most influential in her life occurred in her first assignment.

Trained as a medic but aspiring to be a doctor, Shao found herself thrust into a netherworld between hurricane relief and military “police action” when, in the wake of Hurricane Mitch, she was dispatched to a field hospital on the border between El Salvador and Nicaragua—which was considered a hostile-fire zone. She recalled, “I was supposed to have an officer who ran a battalion aid station. But the day before we left, she got sick, so for the time I was there I was left to run the battalion aid station alone. And it was the best leadership experience I’ve ever had.” Although she didn’t do any highly skilled medical procedures, she felt she helped people take care of themselves.

“All I had was bandages and ointments, but I felt like I had made this enormous difference,” she said. “And these people lined up for literally a mile outside of the base, just to come in and have someone look at their wound.”

Providing care, solving problems, and mobilizing people to do great things with limited resources emerged for Shao to be a compelling definition of what it meant to be a leader—especially when contrasted with the nightmare of insurance forms and bureau cratic regulation she knew to be the norm in U.S. medical care. The experience of doing familiar things in an unfamiliar territory opened her eyes to the tension between the results she truly wanted to achieve and the limits of conventional practice in the U.S. medical establishment. Shao therefore reset her sights: her goal after gaining her medical degree is to establish a clinic in South Boston for immigrants who lack insurance but who are, in her words, “contributing members to society.”

A crucible experience in new territory both demands and teaches an almost preternatural alertness. It encourages an openness to signals and guidance, often from unanticipated sources, that makes it possible over time to get more skilled at detecting impending traps and diversions. See table 2-1 for more leadership lessons drawn from interviews about crucible experiences in new territory.

Reversal

The loss of a loved one, a divorce, bankruptcy, or failure in a major assignment can be profoundly disruptive and disconfirming. At its core is another form of tension: something thought to be permanent turns out to be transient, or something believed to be true turns out to be false. A reversal can bring a leader to understand her situation in a fundamentally new—and more comprehensive—way.

TABLE 2-1

New territory: lessons about leadership*

| • Don’t assume anything about a situation; you’ll likely be wrong if you rely on your first impression. |

| • Leaders need to ask questions as often as they give answers. |

| • Be aware of the lenses you bring to a situation; a leader needs to question himself or herself. |

| • Learn to rely on others; a leader needs to be able to trust other people. |

| • When you’re new to a leadership situation, find common ground by telling stories and getting people to share theirs. |

| • Remember that sometimes events can conspire to make you a leader. |

*These lessons were extracted from interviews.

Case in point: Jeff Wilke, senior vice president of online retailer Amazon.com and widely regarded for his rare combination of being both people savvy and numbers driven, recalled a major reversal that became a turning point in his education as a leader: at a chemical plant where he worked before joining Amazon.com, one of his employees died on the job. He said he went through a lot of soul-searching. “How could this happen? Who’s responsible? Or are we in some way responsible?” he wondered. “You start to question all these things. And to go to the town, to meet his widow, to speak at the plant, to spend a week with these folks and to understand their pain and to try to help them through what’s happened. It’s a transformational experience. So you can convince yourself in an industrial environment that leadership is about making money, making the quarter—and at the end of the day you get to go home to your nice cushy urban or suburban life style. But in the end it’s all these lives that are all wrapped up together, and every so often an event happens that isn’t just about whether we made the quarter. It hits you square in the face.”

Though Wilke had always prided himself on his analytical skills, he recognized that he and his coworkers faced events that could not be resolved through detached calculation. There was a profound tension induced by the need to reconcile two very different modes of thinking and behaving. Within weeks he began to notice a profound change in the way he thought about his job: “I was no longer willing to focus on the business as detached from everything else that happened along with it. I began to give myself permission to have emotion about my work. At the end of the day leadership is about people, and you can’t separate their lives from their work or your work.”

The ability to find meaning and strength in adversity distinguishes leaders from nonleaders. When terrible things happen, less-able people feel singled out, powerless, even victimized. Leaders find purpose and resolve. The experience of reversal, like Wilke’s, challenges the individual to transcend narrow self-regard and reflect on the self in relation to others. Reversals are often places where one becomes intensely aware of his or her connectedness. Above all, they are experiences from which one extracts meaning that leads to new definitions of self and new competencies that better prepare one for the next crucible.

Sometimes the tension at the core of reversal is not loss or failure, but profound disconfirmation, even contradiction. Consider a story from Edwin Guthman, now professor emeritus at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Communications, and widely acclaimed for both his reporting at the Seattle Times (where he won a Pulitzer Prize) and his leadership as national editor at the Los Angeles Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He was working as a press secretary for Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in the early 1960s when he had his crucible experience that taught him something important about leadership.

The time was September 1962, and the place was Oxford, Mississippi, on the campus of the University of Mississippi. Guthman was stationed by a pay phone along with other Justice Department officials in a campus building while an angry and armed crowd threatened to riot in opposition to the registration of James Meredith, a young black man, at the university. According to Guthman, “There were about 300 marshals and five or six of us from the [Justice] Department. And we are besieged by a mob of a couple thousand people. And we have tear gas and we’re armed and we’re able to hold off the mob, although ultimately 29 of the marshals are wounded by gunfire. The injured are laying on the floor of the Lyceum Building. And there’s an Army division on its way down from Memphis.”

That’s when he and other members of his group decided it was time to ask permission to use their weapons. Deputy Attorney General Nick Katzenbach made the call to Robert Kennedy. The answer? An unequivocal “No!” Guthman recalled, “And there’s a discussion about this. We’re really pissed off because we think we’re going to get killed!” Most of all, Guthman himself felt outraged that Kennedy, this young thirty-five-year-old attorney general—with no previous military experience, at that—was leaving his own staff people in such a vulnerable position.

But of course none of them were killed, and a few hours later the army showed up and things quieted down. Later, the group involved met in the Justice Department to critique how they’d handled that situation. They realized that if Robert Kennedy had given them permission to fire, it would have been an utter disaster. “Imagine if we’d fired into this mob!” said Guthman. He and his colleagues met several times in subsequent days, on their own and with no prompting from Kennedy, to try to understand how they got to a point where they were urging the attorney general to take arms against fellow citizens.

That painful and in many ways embarrassing process of reflection proved fateful to Guthman. Despite his initial anger at Kennedy—an anger fueled as much by Kennedy’s youth and lack of military experience as by Guthman’s fear of impending harm—Guthman volunteered Kennedy’s decision as a powerful influence on his behavior as a leader in years to come. In his words: “We realized how important that decision was, but we also realized that we had made some mistakes … Looking back, I’ve often learned from this. When something happens, go in and try to figure it out, not to blame somebody, but so you don’t make the same mistakes. You should always take the time to confront the problem; face up to it.”

It was a powerful lesson about the need to recognize the tension between personal ego and the welfare of others that can accompany high-stakes decision making. Guthman’s resolve as a leader to think decisions through and to ask the tough questions of himself and the people who worked for him was tested several times over the course of his career. For example, when the Philadelphia Inquirer published an editorial criticizing Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, and Guthman and his staff were roundly chastised for their position, he spent weeks meeting with Jewish organizations in his own investigation to determine whether the paper had made the right decision.

Reversal tests both wherewithal and imagination. It stretches to the limits an individual’s self-confidence. At the same time, reversal sharpens the ability to see beyond or through bleak circumstances to another set of outcomes. Reversal teaches leaders the power of optimism and the courage to reflect honestly on one’s own shortcomings. See table 2-2 for more examples of leadership lessons learned through reversal.

TABLE 2-2

Reversal: lessons about leadership*

| • Leaders need to remember the importance of interdependence—that life is not just about the business; an organization is a community of human beings. |

| • Leaders need to care about interpersonal relationships and be willing to be cared about. |

| • A leader doesn’t have to be superhuman or have all the answers, no matter how much people may wish it to be so. |

| • Failing is only a step on the path to success. |

| • Trouble doesn’t last forever. |

| • Know what you stand for as a leader before crisis hits; when things are crashing down around you and people are looking for your leadership, it’s too late to figure things out. |

| • Integrity is the only thing you have that’s truly yours. |

* These lessons were extracted from interviews.

Suspension

Crucibles of this type involve a hiatus, often one that is unanticipated, during which a well-known set of behaviors and routines is set aside, sometimes forcibly, and replaced with a regimented structure or no structure at all. Suspension has at its core a tension between realities—old and new, immediate and indeterminate, comforting and uncomfortable—and with that tension an opportunity for both exploration and reflection. College, prolonged unemployment, and jail time can be crucibles, particularly as they afford time and space to explore other possible selves and lifestyles. The same can also be said for entry into more severely structured settings—“total institutions” like a boot camp or a convent—that demand a wholesale change in identity.1

Suspension challenges leaders to clarify—or, in some instances, to create—their personal mission and purpose; to cement their own personal foundation of beliefs and values.

Ali Omar, a captain in the Palestinian security forces who had been active in the Fatah branch of the Palestinian National Liberation Movement since the age of fifteen, recalled a time in the heat of battle and its aftermath when he realized that he could be imperfect and yet still be an effective leader. From an early age, he had looked to the commanders under whom he served for his models of leadership. One leader in particular, the acting commander of a major city force, had a profound effect on him. “He had joined the forces after the Israeli occupation of the West Bank,” Omar recalled. “I believed that he knew everything, that he had the answer to all questions, the solution to all the problems, and the knowledge to lead us in critical situations.”

At a decisive juncture, however, this commander faltered—hesitating and looking confused—leaving Omar and his comrades to their own devices. With the commander unable to lead them, Omar suddenly found himself in charge of leading a group of men to defend a neighborhood. “[The commander] sent me a message saying simply that I had to depend on myself and to stop sending correspondents asking for orders,” he said. “I recognized then how difficult it is to be a leader, especially when defending a city and protecting civilians and trying to give the right orders to the soldiers without making a mistake that I would regret to the last day in my life.”

Importantly, the order for Omar to make his own decisions came not from a commander too busy to attend to the pestering of an underling; it came from a man who had suddenly lost his will to lead, who had withdrawn into a shell from which pleas could not extract him.

Captain Omar described the feeling as a “slap in the face,” akin to being rejected by a father figure. Even worse, this father figure had revealed himself to be a coward, afraid, self-absorbed, and completely without regard for those in his charge. Omar felt acute pain in those moments. He felt both empathy for and fury toward his commander. He questioned his own ability to lead but would not walk away from his men. He concluded, “I learnt from this great experience that nothing can change the fact that all of us are human beings who may make mistakes any moment that can cause a lot of losses. But a man can also take the risk and act in an unexpected way and develop himself to a certain level where he surprises everybody, including himself. And I think this is what happened to me.”

Among other things, Omar decided in the wake of that crucible to dedicate himself to something he’d never considered possible previously: to become an active participant in the process of creating a viable Palestinian state and to help secure its place in the international community through diplomatic service.

Suspension challenges individuals to create structures, first for themselves and then, potentially, for others. By snatching people out of a familiar web of relationships that appear self-sealed and lasting and inserting them into what can feel like free fall, suspension calls forth the ability to impose meaningful rules on oneself—to create a foundation of values and meaning on which to stand and then perhaps to extend that foundation into organizing principles for one’s life, one’s pursuits, and one’s relationships. Table 2-3 offers further examples of leadership lessons learned through the experience of suspension.

TABLE 2-3

Suspension: lessons about leadership*

| • It is crucial for you, as a leader, to have a purpose or mission; people respond to your earnestness and authenticity as much as to your logic. |

| • Leaders need to be at peace with themselves before they can ask others to be peaceful; leaders need to be clear about what they value if they expect others to be driven by their values. |

| • Leaders don’t need to be bulletproof: although it’s scary not to have all the answers, it can help engage others in the decision-making process. |

| • Leaders need to roll with the punches and be ready to acknowledge when they’re wrong. |

*These lessons were extracted from interviews.

_________

Each story just recounted about crucibles involving new territory, reversal, and suspension had at its core a tension, a kind of potential energy, that demanded a behavior or maybe an answer that either did not exist previously or went unrecognized. Although some of the lessons in leadership learned from these crucible experiences may not seem particularly new or noteworthy, the manner in which these leaders recounted them was dramatic indeed—and therein lies a key aspect of effective leadership.

As the scholar Noel Tichy argues, leaders must be teachers—and the leaders in this chapter offer precisely what Tichy calls a “teachable point of view.”2 He argues that leaders’ responsibility is not only to provide direction or judgment in the moment, but to strive continuously to develop leadership in others, now and into the future. Stories, especially stories of trial and transcendence, provide a foundation for a teachable point of view. They provide the grit and detail, the suspense, and the credibility that turns what might otherwise sound like a homily into something that screenwriter Robert McKee once termed “advice with substance.”3

Let’s turn now to the lessons that each of the three types of crucibles have to teach about learning itself.

LESSONS ABOUT LEARNING

Although leadership lessons gained from crucible experiences are valuable enough in themselves, crucibles go a step further to offer lessons in learning as well: the subtext to virtually every crucible story reveals the conditions associated with gaining new, useful knowledge. The men and women who recounted their stories in this chapter, then, also gained deep insights about how they learn—about what it takes for them as capable and accomplished people to learn new things, to resolve the tensions inherent in a crucible, and to raise the level of their performance. They each described a powerful flywheel effect: once alerted to what it takes to draw insight from experience, they began seeing learning opportunities all around them.

Lessons about learning are arguably more valuable than leadership lessons, per se, because learning is what enables an individual to grow and adapt to changing circumstances. Indeed, lessons about learning make it possible to even recognize that circumstances are changing, that adaptation is needed, and that growth is possible. Liken it to the difference between a novice and an expert in virtually any artistic or athletic domain (a theme to which we return in the next chapter): a neophyte delights in accidentally executing a difficult move, be it a dance step, a chess maneuver, or a tricky approach shot in golf; but an expert appreciates the combination of skill and practice it takes to execute consistently and notices the learning opportunity in even the most elegant and seemingly flawless move. Learning about learning makes it possible to take control of one’s education, to learn better and faster, and to adapt and grow across time, across circumstances, and across organizations.4

Lessons about learning often had to be teased out of offhand remarks, such as Bob Galvin’s comment (from the example in chapter 1) about the encouragement he received from a factory foreman.5 Sometimes these lessons are overlooked or taken for granted—but that doesn’t mean they’re not critically valuable. Some leaders, like performers in other domains, are unconsciously competent. They literally cannot describe what they do when they lead or how they learned to do it. That doesn’t make them less effective or less likely to learn from experience. However, those who are aware of how they learn—and learn best or most deeply and durably—seem to learn with greater economy and speed. They are also better at explaining what they know to apprentices and protégés, meaning that they are likely to leave more leaders in their wake. Their conscious competence does not slow them down or render them paralyzed by self-analysis. In fact, it enhances their ability to spot learning needs and opportunities in themselves and in others.

How does learning about learning manifest itself? In my interviews and in discussions with leaders about crucibles, I would ask not only what they learned but how they learned it. I asked, “What made it possible for you to learn what you learned? If I were to change one thing about your story that would have made it ordinary, what would that be?”

Answers to those questions yielded valuable and sometimes surprising clues as to how some leaders learn from experience. Most importantly, learning from crucibles (and, I’ll later argue, learning from any experience) tended to occur when the individual could identify a connection among three things: their personal aspirations (i.e., what they pictured as their best or ideal self), their motivations (what they most deeply valued), and their learning style (how they learned best or most effectively).6

For example, Jeff Wilke earlier recounted the epiphany that occurred to him with the tragic loss of an employee at a plant he managed. He described it as an insight about the connectedness among people that a leader needs to comprehend, honor, and support. He also talked about the insight that crucible had teased out of him about himself—how he needed to more effectively resolve the tension between the emotional aspects of work (and himself) and the analytical. When pressed to “go deeper” and explore the conditions surrounding that learning, he began to talk about the importance of being out of his comfort zone, to be confronted with facts and with feelings that were unfamiliar, and to acknowledge that the whole package—situation, resources, emotions—created an opening for better understanding the world and himself.

Ling Yun Shao’s experience as a medic in El Salvador clarified her self-perception. Moreover, in comparing her role in that village with what she knew she’d do as a doctor in an American hospital, Shao got a rare glimpse into both her core motivations (healing, not prestige) and her preferred learning style (hands-on, interactive, kinesthetic).

Sidney Harman, founder of Harman International (previously Harman-Kardon) and former deputy secretary of commerce about whom Warren Bennis and I wrote at length in Geeks and Geezers, talked about two important insights he had regarding his own learning style. First, he believed that through his daily journal entries, he could literally see what was on his mind: what questions he needed to answer and what answers were forming. (Brandeis University president Jehuda Reinharz and legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden also told me that writing helped clarify their own learning.) Second, Harman claimed that by spending time with masters in a given field—working alongside them, interviewing them as a journalist or historian might—he “borrowed energy” from their passion and depth of understanding to aid him in gaining insight into that field quickly and effectively. For example, in order to deepen his understanding of what jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis wanted his horn to sound like when reproduced by Harman-Kardon stereo equipment, Harman studied and questioned Marsalis the way a music critic might.

But how do the seeds for such lessons about learning come about in the first place—and how does a leader learn to recognize and cultivate them? Engaging in what I call a Personal Learning Strategy is key.

The Personal Learning Strategy

The ability to recognize the tension at the core of a crucible and to convert the energy of a crucible to productive uses through awareness of one’s own aspirations, motivations, and learning style—these represent the foundation of a Personal Learning Strategy. Such a strategy enables two things: (1) it guides an individual in identifying learning needs and opportunities, and (2) it provides insights about what conditions, resources, and supports are most likely to result in improved performance.

For some leaders, the interviews I conducted about crucible experiences turned into explorations of the contours of the individual’s Personal Learning Strategy: what an individual might have described as “restlessness” or “entrepreneurial spirit” would, on closer inspection, reveal an intuitive self-understanding that learning can be either pleasant or unpleasant but that it most likely occurs under fairly specific circumstances. For example, Bill Porter, founder of the first completely online brokerage, E*TRADE, prided himself on the “problem-finding” skills he applied with as much gusto to organization building as he did to helping develop satellite stabilizers, measurement devices, and electronic exchanges.

In other instances, the people interviewed clearly recognized how they learned best—and they routinely engaged that knowledge as a guide for their next project or assignment or personal challenge. Sometimes, as in the case of former SEC chair Arthur Levitt Jr., they became seekers of crucibles, constantly looking for the kinds of challenges that would stretch them. In a career of more than fifty years, Levitt served in the air force, was both a cattle rancher and an editor at Look, and served, under President Clinton, as chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “What I believe is important in life is to keep as many doors open as possible,” Levitt explained. “You close a door when you fall in love with a community and say you won’t move. I’ll move any place. I couldn’t care less where. And I think that’s important. You re-pot yourself.”

A Personal Learning Strategy, then, is an individualized routine or recipe for learning, with a special quality to it: its function is to challenge other routines—that is, to uncover patterns of activity that can, through repeated use, become habitual, stagnant, resistant to change, obsolete, ineffective, and, ultimately, destructive. The ability to engage this unique routine is nearly as important as the routine itself. The same attentiveness to situations that enables some people to spot trends, to see market opportunities, or to discern openings for negotiating through an impasse gets applied internally. The same resolve to act that propels an organization to move when an opportunity is spotted gets applied to the self. Warren Bennis, interviewed about his experience as a university president, talked about learning as a spark of insight, sometimes a “premonition about what I need to do or to be in order to avoid getting mired in habit.” People attuned to learning are what Saul Bellow once described as “first-class noticers”—not just of the world, but of themselves, too.

On the other hand, a Personal Learning Strategy is not just the state of self-awareness or situational awareness described in recent writings as “emotional intelligence.” Those qualities are real and important, but they do not quite capture the potential of a Personal Learning Strategy: the potential it contains for propelling an individual, a leader, forward into situations and relationships that will cause him or her to put to the test enduring, but potentially obsolete, ideas and behaviors, or to encounter things (relationships, cultures, technologies, and worldviews) that are not only unfamiliar but potentially antagonistic to a comfort able current reality.

But how exactly do Personal Learning Strategies connect to crucible experiences? On one level, crucibles are quite often the catalyst not only to learning important things about leadership but also to insights about learning—about the conditions and resources in and through which learning is most likely to occur. At another level, once a person recognizes his or her Personal Learning Strategy, that strategy can guide the individual to detect the need for challenge and learning, for growth and adaptation, and for situations in which they are possible. A Personal Learning Strategy leads, perhaps inevitably, to future crucibles.

A Personal Learning Strategy can also alert one to learning opportunities that are far less special (or extreme) than the crucibles we’ve been describing to this point. It can enhance a person’s alertness to the myriad opportunities for learning that occur in everyday life—opportunities for conscious experimentation and testing in real time. Mellon, the turnaround specialist who earlier described how panic had taught him to calm himself and others, explained it this way:

Whether I am at the podium at an investor conference, with all these razor-sharp analysts trying to reveal some hidden weakness, or in a small group with a bunch of junior people who want desperately to believe that we’re going in the right direction and that somebody—anybody—has a plan they can trust, I feel like I’m on stage and I’ve got to perform. I’ve got to project confidence even when I’m unsure. I’ve got to truly believe that what I am asking people to do is possible, that it’s going to lead to results we want and need. I’m acting—for sure—but I’m not pretending. I am walking a tightrope with all the confidence of a professional, knowing fully well that if I fall I’m in serious trouble, but never looking down. That’s the work of leading.

How did Mellon get to a point where he felt confident in his ability to perform? “It takes practice,” he said. “I’ve learned a lot from experience and reflecting on that experience.”

The ability to experiment in real time is not exclusively a product of crucible experiences. It is an ability, however, that seems unusually common among leaders who have had a crucible experience that caused them to reflect on their own Personal Learning Strategy. Once aware of the way they learned from experience, they saw opportunities for learning all around them. Not unlike stage actors repeating their performance of a particular play, they could be “in role” but still able to improvise in tone or emphasis and thus to judge the reaction of the audience or their fellow actors. Not unlike martial artists Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan, who perform exquisitely complicated bodily contortions with speed and grace, these leaders are intensely aware of themselves and their surroundings even as they seem to observers to be a blur of motion. And not unlike consummate musicians who tune themselves and their instruments in midperformance, these leaders demonstrate that they can practice while they perform.

Table 2-4 lists more lessons on learning extracted from interviews about crucible experiences. Notice as you read through them the very individual and yet practical quality to the lessons people gained from a wide variety of experiences.

One thing that came across during the interviews for this book is that many, if not all, of these leaders are what I call “egoless” learners. They are constantly in search of new ideas and new ways of thinking about and solving perennial problems. Like trapeze artists, they let go in order to move forward—even when they’re uncertain that the swing will be there to catch hold of at the precise moment it’s needed. Calling them egoless doesn’t mean they don’t have egos—not by a stretch. Rather, it means that they refuse to let what they know get in the way of learning new things. Morgan McCall underscored this point in his study of successful executives: “[They] took responsibility for their own learning. Instead of denying critical feedback that hurt, they swallowed their pride and took it to heart. Instead of blaming everything on an intolerable boss, they dug out messages for themselves. Instead of dismissing other people because they were too old or too young or too abrasive or too soft or too different, they adopted the attitude that you can learn something from everyone.”7

TABLE 2-4

Lessons about learning

| Crucible type | Lessons about learning* |

|---|---|

| New territory | • Leaders learn through tests and challenging situations—not from things with which they’re already familiar. |

| • Leaders learn best when out of their comfort zones and forced to try on new behaviors. | |

| • Leaders learn best from the best: search out the leading practitioners, and try to find out both what they do that’s different and what they can teach you about the inner game. | |

| • Everything is theoretical until you’ve been there. Seek out new places and experiences to build a stockpile of examples. | |

| Reversal | • Face your fears: rather than sidestep or delay, address your deepest worries and concerns directly; then gather yourself up to move on. |

| • Recognize that panic often precedes learning—and that calm often comes after panic. | |

| • Don’t fail to learn from failing. | |

| • While not endangering yourself, sometimes it’s good to put yourself to the test. | |

| • Be willing to fail in order to learn. | |

| Suspension | • Practice before you preach: take the time to practice a new skill or behavior alone—in quiet and without fanfare—before you take it public. |

| • Learn to use every moment to reflect; i.e., if you take a deep breath or meditate, you can engage in short but relaxing bursts of creative thought. | |

| • Recognize that there are times, like being fired or laid off, when you may get an unexpected opportunity to think, to sort out your priorities, and to explore what you could be—rather than being shackled to who you were. |

*These lessons were extracted from interviews.

Experiences, crucible experiences most profoundly, may provide the opportunity and the reason to learn, but, like a horse drawn to water, individuals won’t learn from experience if they are not prepared to learn. Thus, a crucial precondition for mining experience for insight is awareness of what it takes to learn. To understand how people achieve this awareness and how the flywheel of learning starts to move, we must venture deeper into what goes on inside a crucible—the topic of the next chapter.