[ 8 ]

EXPERIENCE-BASED LEADER DEVELOPMENT

The Organizational Dimension

Experience is not so much what happens to you as what you make of what happens to you.

—Aldous Huxley

WHERE DO THE MOST IMPORTANT formative events for leaders occur? If you’ve read to this point in the book, you already know what the answer isn’t: it isn’t in the classroom, the assessment center, the company off-site, or the annual performance review. It isn’t in the conventional domain of leader development, and it isn’t within the purview of most performance management systems. Rather, the richest and most memorable events are leaders’ personal crucible experiences.

So, do organizations take full advantage of these rich development opportunities? Not really. In fact, my research suggests that implementing a process through which to leverage experience poses fundamental challenges for organizations. Crucibles are hard to schedule. It can be difficult to tell when they are occurring—for individuals or for organizations. There’s a good chance crucibles won’t occur on the job. And if they do occur on the job, they don’t stop with the closing bell and restart the following morning. Finally, crucibles are idiosyncratic; they won’t be the same for everyone in either their origin or their impact.

There is, however, an upside: crucibles are frequent and free.

Organizations can tap into the power of crucibles by adopting an experience-based approach to leader development. An experiencebased approach represents a comprehensive new way of developing leaders because it weaves together life experience, on-the-job experience, and specific skill development. In other words, employees need more than a laundry list of classes and programs tenuously linked to career development. And organizations need to find ways to draw personal experience and aspirations into the development process, instead of treating these facts of life as if they were out of bounds. What I propose is an approach that can be adapted to the needs and opportunities of people at all stages of their careers and that can help them on their journey from novice to adept to eminent leadership. It is an approach that can also adapt to the changing needs of organizations operating in complex and uncertain environments.

This chapter will examine the efforts of several organizations that have sought explicitly to incorporate experience into leader development. We will also take a closer look at a pair of organizations that have fully embraced an experience-based approach to leader development and have benefited enormously as a result.

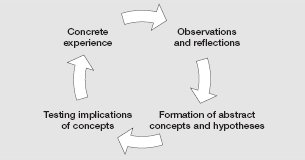

WHAT EXPERIENCE-BASED LEADER DEVELOPMENT CAN DO

The goal of experience-based leader development is to equip employees so that they can mine their experiences—continuously and intensively—for insight into what it takes to lead, what it takes to grow as a leader, and what it takes to cultivate the leader in others (peers and superiors as well as subordinates). The experience-based approach builds from the research reported in the preceding six chapters and from the classic works on learning, especially the writings of John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, Paulo Freire, and David Kolb and their specific applications to leadership by Warren Bennis, Ed Schein, Chris Argyris, Donald Schon, and Morgan McCall.1 (See the box, “The Learning Cycle.”) Their inspiration will be obvious in what I describe as the core “moments” in experience-based leader development: preparing, deploying, and renewing.

However, I want to do more than create yet another interesting but difficult-to-assemble model. Instead, I hope to link the leader development activities most organizations already have in place—assessment centers, classroom training, career development, succession planning, performance management, and the like—with real work assignments, innovative uses of technology, and, most importantly, individual Personal Learning Strategies to grow more leaders at all levels faster than ever before.

Ambitious though this undertaking may appear, the logic is simple: we know that concrete experiences—in particular, crucible experiences—are not only a vital part of the learning process; they are often the best teacher too. But we also know that experience by itself is not enough. Individuals must prepare to make the most of experience. They need observational skills, comfort with techniques of experimentation, and more than a modicum of self-understanding in order to extract insight from experience. The burden or responsibility for acquiring requisite skills, perspectives, and self-understanding—the elements of a PLS—falls squarely on the shoulders of the individual, not the human resource department. Only an individual can understand her own aspirations; only she can be truly aware of the prism of past experiences, personal values, and preconceptions that shape what she sees; only she can honestly assess how she learns (and why she learns that way); and only she can choose the level of risk she is willing to take in order to learn.

We know that organizations have at their disposal resources that individuals need, like self-assessment tools, classrooms, coaches, and experiences—stretch assignments, foreign postings, or mentoring relationships—that can enable them to deploy or apply valuable skills and teach valuable lessons about leading. And we know that organizations can create processes, like assessment and tracking and personal development planning, that can guide the selection and grooming of leadership candidates. But if those developmental experiences and processes do not align with individuals’ aspirations, motivations, and learning styles—their Personal Learning Strategies—there is little reason to believe that they will have the effect that organizations hope for. And if the results of personality assessments and learning diagnostics are not shared with individuals in a way that educates them as to their abilities and options, then the value of testing and tracking will be limited by more than half. In other words, organizations routinely deploy people into assignments, but often development is only loosely coupled with deployment. Managers either don’t ask what a candidate should learn from an assignment, or they do but don’t follow up to see whether what was intended was actually achieved. Filling the leadership pipeline is not just a supply chain problem.

Finally, we know that the ability to renew and enhance oneself by learning from experience is not something that we should automatically expect from incumbent leaders or from candidates for leadership positions. In many organizations, individuals have advanced up the hierarchy in the early part of their careers by outperforming their peers (what researchers refer to as a tournament model of career mobility).2 This can easily lead them to the conclusion that continued success—especially movement into the executive suite—will come about as a result of honing and refining what they already know, not from experimenting and learning new things.

An experience-based approach does not abandon the time and money already invested in assessment centers and training programs. It leverages those investments. But it does call for a reorientation on the part of top management—the men and women ultimately responsible for identifying and developing the next generations of leaders—and on the part of the professionals formally charged with recruitment, training, and succession planning.

Organizations, in short, must commit themselves to providing robust resources and durable processes that will prepare, deploy, and renew existing and prospective leaders by means of a more active and creative use of experience. That commitment must be visibly enacted and supported by top management if an organization truly hopes to make learning from experience a central value.

EXPERIENCE-BASED LEADER DEVELOPMENT IN ACTION

Fortunately, both the profit and the not-for-profit sectors can provide examples that can give us an inkling of the shape and the potential benefits of experience-based leader development. Companies like Toyota, Boeing, and General Electric and organizations like MIT’s Leaders for Manufacturing program have undertaken initiatives that leverage experiential learning.

Yet as we will see, few organizations successfully integrate crucible experiences into leader development, even when those most responsible for leader development recognize—indeed, testify—that experience is the best teacher. Indeed, when it comes to looking for ways to integrate experience into leader development, most tend to stay comfortably within their own boundaries. They restrict their search to allied industries and settings, leaving aside the possibility that someone in a nonindustrial or nonbusiness setting may have already solved their problem. They enact what I described in chapter 5 as the banking model of learning: a semiindustrial process in which cost per unit is the key performance measure and knowledge is something deposited in students’ heads for later use. They encourage aspiring leaders to “get experience,” take on stretch assignments, take risks, and the like, but provide precious little guidance in how to mine experience for insight.

Even when organizations recognize the influence of crucible events, they find it difficult to engage leaders and leadership candidates in dialogue about them. The chief leadership officer at a major pharmaceutical company put it simply: “Incorporating life experiences into work experiences is taboo, even if it would give more insight into individuals and what shapes them as leaders,” he said. “So, it’s taken us a long time to get to the point where we are now: experimenting with a developmental process that actually understands [very senior executives] as individuals.”

The irony, he went on to say, was that those executives have proved very open in talking about what has shaped them as leaders. My experience in talking with hundreds of business and governmental executives echoes this point: given the opportunity, leaders want to talk about their developmental experiences; they practically gush with exuberance. The limiting factor, therefore, may not be individual privacy but organizational ability to make use of that very valuable data. It’s almost as if organizations—and especially the people responsible for leader development—are residents of a high-rise, witnessing a mugging ten floors below: they very much want to help but don’t know what to do.

Toward the end of this chapter, I present as a partial remedy two examples that illustrate the real potential of crucibles for leader development—in two organizations on opposite ends of virtually any spectrum: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons) and the Hells Angels (an outlaw motorcycle gang).3 Aside from their appeal as exotic stories, these two cases demonstrate experience-based leader development in action.

But first, let’s examine more closely the three core moments in experience-based leader development: preparing, deploying, and renewing.

Preparing

Huxley made the point beautifully: experience is not so much what happens to you as what you make of what happens to you. Preparation, like the stance a tennis player takes while waiting to receive a serve, is about being in motion, observing and adjusting, anticipating whatever comes. Motorola’s Bob Galvin underscored that point when he told me, “You have to have a disposition to being in motion, anticipating what’s coming.”

Organizations often do an excellent job of teaching analytical skills—how to diagnose problems and fix them—but many struggle with helping leaders hone their skills at sensing and observing. They might benefit from a closer look at what’s been going on at Boeing.

The Boeing Company

A comprehensive program of preparing leaders to learn from experience has been under way for several years now at Boeing—and the company has linked the effort directly to business strategy. Best known for its eponymous commercial aircraft, Boeing has grown by leaps and bounds over the past decade, acquiring rival McDonnell Douglas, the space and defense business of Rockwell International, and Hughes Space and Communications. The technical integration tasks by themselves were monumental, but of equal concern to Boeing’s leadership has been its ability to prepare the next generation of executives to lead the network of businesses as a coherent whole. Leader development and training became a central initiative in achieving integration, in two distinct ways.4

The first prong of Boeing’s strategy was to create a leadership center that would serve as both a training ground and a crossroads for all of the company’s leaders. Collaborative learning features prominently at the center, particularly experiences that familiarize leaders from disparate corners of the company with the organization’s products and technologies and that help form shared mindsets among the next generation of leaders. At center stage is an elaborate computer-based simulation that offers leaders an opportunity to work together in high-pressure situations.

Consider Boeing’s simulation of an as-yet-infant underwater transportation industry. The simulation centers on a company it calls AquaTek and two other fictional competitors. Participants in the simulation are assigned to all the major functional roles one might find in a small but growing business and are given realistic budgets and constraints. They draft learning contracts based on their experiences during the simulation, and these, in turn, become a vital guide for the coaches responsible for follow-through. Even during the simulation, coaches review the experience with participants as individuals and in their teams.

The simulation experience is like spring training for major league business. According to Ron Marcotte, deputy general manager of Air Force Systems for Boeing, “It gets people out of their comfort zones and stirs them up to learn about everybody else’s business. On the last day, you end up presenting to the real CEO, and nerves go to a fevered pitch.” The whole process is ideal preparation for future leaders and has the added benefits of providing a crossroads for the company’s far-flung leadership and giving peers the opportunity to witness one another’s business strengths directly.

The second prong of Boeing’s strategy for preparing leaders to make the most of experiential opportunities involved a pilot effort called Waypoint. The brainchild of a vice president of human resources and a small cadre of researchers, Waypoint sought to leverage the findings of Morgan McCall’s research (and subsequent development at the Center for Creative Leadership) to create a database of leadership lessons learned from a variety of assignments that Boeing managers had described in interviews.5 The objective was to generate a resource that managers and their career coaches could consult once they had identified developmental needs by mapping out “the invisible markers, the key turning points in managers’ careers.”6

After five years of intensive interviews and systematic tracking of a cross section of Boeing managers (121 in total), the Waypoint project accumulated enough data and insights to create a series of career-planning tools, including a growing catalog of assignments classified by the developmental opportunities, and a companion Web site on the company portal that allows individuals and their career counselors to link to resources that Boeing managers recommended on the basis of their experience.

Learning from experience, interestingly enough, has become the hallmark of an innovative approach pioneered at an educational institution best known for its research labs, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MIT’s Leaders for Manufacturing Program

In the mid-1980s, when the United States was in the midst of a debilitating recession and the international outsourcing of manufacturing employment was just in its infancy, a group of faculty, government, and industry representatives convened at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and launched a no-holds-barred investigation into the roots of America’s industrial malaise. The result was the provocative 1989 book Made in America, which pointed to a vacuum in the leadership ranks of major manufacturing firms.7 Not only were U.S. companies shortsighted when it came to product development and unwilling to learn from the best global competitors, but also the best leadership talent was assiduously avoiding manufacturing companies and the manufacturing function, in particular. Intent on addressing those shortcomings, a group of companies banded together to underwrite the creation of a program of education and research called the Leaders for Manufacturing program, or LFM.

LFM fosters leadership in both technology and organization, and nowhere is this emphasis greater than in the education of the Leaders Fellows. From the moment of their arrival on campus, Fellows are immersed in discussions about, and practice in, leadership. Throughout the two years of the program, leadership occupies center stage as an organizational problem, a technical challenge, and a personal goal. And with an alumni network of well over seven hundred members, it has also become a focus for continuing education and dialogue among cohorts of graduates.

The LFM starts from the assumption that the most important lessons about leadership cannot be taught in traditional ways. LFM director Donald Rosenfeld described it this way: “Experience is critical to the learning process. So, too, are opportunities to reflect on practice … to connect the analytical side of leadership training with personal experience.” The program accomplishes this in several ways. For example, in the first week, students—who average eight years of work experience in diverse backgrounds—are immersed in a unique program titled “The Universe Within,” devoted to opening students’ eyes to how they learn, how mental models shape their perceptions and constrain their ability to talk across cultural and disciplinary boundaries, and how they, as a cohort, can achieve a measure of collective intelligence based on teamwork and competition. This focus on observation and inference provides a valuable foundation for student internships, the crown jewel of the program.

At the end of the first year of core courses in management and engineering, students are dispatched to six-month internships at sponsoring companies, where they are tasked to work with (and in some instances to lead) a team in resolving a significant manufacturing problem. The internship represents a unique laboratory for applying and evaluating ideas about world-class manufacturing and supply chain management, but it also provides practice fields for students to gain experience in leading organizational change. Subsequent classes on leadership and change draw explicitly on students’ experiences and challenge them to make sense of what they learned on the factory floor.

Learning does not end with graduation. In fact, one of the most distinctive features of the LFM program is the size and vitality of its alumni network. The network holds annual meetings to discuss and debate new developments in manufacturing practice and business strategy and to counsel the program’s administrators about how to keep the educational process and content in sync with industry developments. Moreover, the trust and mutual respect forged in the common, crucible-like experience of classes, team working, and internships has made the network a valuable source of advice for its members, akin to what I described earlier as the YPO Forum.

Of course, all the preparation in the world won’t help if you tense up and revert to old habits in the face of a crucible. That’s why it is essential for organizations to find ways to support leaders so that they deploy newly acquired skills.

Deploying

Most organizations do not manage their leadership assets as carefully or as systematically as they do their capital assets. They treat succession as a queuing problem and discover too late (and too often) that the people currently in the pipeline lack some of the skills or the perspectives that the CEO and the board now realize are essential for success in a changing competitive landscape.8 Fact is, they know very little about the people ten or fifteen years removed from the top leadership slots: how they think, what they’ve learned from the assignments they’ve had, what they care about, or how they define success for themselves and for the organization.

While there is no denying that demographic shifts are part of the root explanation for the troubles facing industry, equal weight needs to be given to the failure of many organizations to grow leaders through work.9 However, several organizations renowned for their financial prowess and their accumulated intellectual capital may hold promise for how effective deployment of experience can lead to more effective leader development.

General Electric

Although this leadership powerhouse has been examined many times, there are still some foundational lessons to learn from General Electric. Most important is the way in which learning and doing are woven into the very fabric of its process and culture.

General Electric, particularly under Jack Welch, is legendary for the attention it gives to selecting and developing leaders at all levels. Welch assiduously tracked potential leaders throughout the organization, leveraged the differences in GE’s businesses to give people opportunities to lead in a wide variety of circumstances (e.g., growing versus plateauing markets, capital asset intensive versus human capital intensive, unionized and nonunionized), and used every speech, supplier visit, and public appearance to search out the best talent available in the open market. But he was also legendary for declaring that the task of leader development was too important to be left to human resources—in large measure because, as colleague Steve Kerr (former chief leadership officer and director for many years of GE’s Crotonville management education center) argued, “Starting in 1992 Welch decided it was folly to try to prepare for a future that was so uncertain. We decided instead that most of our efforts would be spent making leadership of change a core competence of the firm.”

The key phrase from Kerr is “a core competence of the firm.” In other words, it’s not just about growing a stratum of leaders; it’s about increasing the number of leaders at all levels. Rather than limit the objective to senior management, Welch (and subsequently his successor, Jeff Immelt) pledged to drive leadership of change deeply into the organization—to create what Joseph Raelin refers to as a “leaderful organization”—and to do so by adroitly combining learning and doing.10 The Work-Out methodology—lionized for its contributions to performance improvement—is just as significant for the combination of hands-on experience and the training it gives to line employees, first- and second-level supervisors, and managers in how to collaborate in solving problems and how to make and implement effective decisions in a timely way. The experience gained in Work-Out lasts a very long time; hence, the investment in training pays out year after year. The same can be said for GE’s dedication to Six Sigma and Change Acceleration: while ostensibly focused on continuous performance improvement, each builds off a robust philosophy of structured experimentation, analysis, and learning.

Like many professional services organizations, management consultancies live or die by their intellectual capital—not just what they’ve documented in software or manuals, but also in the knowhow, the tacit skills that employees carry in their heads (and take home with them at night). Poor or inexperienced or inflexible leadership can drive intellectual assets out of the firm literally overnight. For this reason, some, like Accenture and Deloitte, strive to grow leaders at the same time that they solve client problems.

Accenture and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

Like many professional services firms, Accenture (my current employer) and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu organize themselves around projects. But unlike many peer organizations, they use projects not just to deliver services to their clients, but also to grow and test leaders.

Consulting engagements vary in length from a few months to a year or more, but in that time consultancies like Accenture use team and peer reviews to provide project leaders with a continuing stream of feedback on their performance and that of their teams. Given the intense pressures created by deadlines and client expectations, these firms cannot afford to let problems arise without being quickly resolved. Feedback that is fast, honest, and constructive is absolutely essential. So, too, is managers’ ability to incorporate the feedback immediately into changed practice. That’s why in these two companies, in recent years significant investments have been made in growing both the interpersonal and the technical skills of leaders at the project level.11

Accenture’s MyLearning and Deloitte’s Global Learning technology platforms are aimed at providing a wraparound resource for their professional staffs. That is, they create an Internet-based storehouse that allows individuals to locate their personal learning plans (often constructed in collaboration with career counselors), to access a rich portfolio of online training materials at a moment’s notice, to identify projects (both internal and client-facing) that will provide a chance to acquire or practice specialized skills, and to catalog their accomplishments.

Deloitte’s Career Value Map is an interactive online career development tool that seeks explicitly to align individual interests with experiential opportunities as they arise—for example, openings in new or ongoing client projects. According to Nick van Dam, Deloitte’s chief learning officer, “Half the task is helping individuals get clear about what they want to accomplish in their careers. When they can state their interests and ambitions more clearly, we can guide their search for relevant experiences.”12 Accomplishing that within a global network of over ninety thousand employees is no simple job.

Just as it has become apparent that change is a continuous process in most organizations (and certainly business organizations), so too must learning be a continuous process, especially for leaders. To treat learning as episodic—which a curriculum of periodic seminars inevitably does—says that learning occurs only during prescribed times. In experience-based leader development, renewal is a continuous activity.

Renewing

Geeks and Geezers introduced the term neoteny to characterize lifelong learners: men and women who march through their lives (not just their work) with their “eyebrows arched in surprise.”13 They delight in learning new things, especially when insight leads to enhanced performance. Leaders who exhibit neoteny are never bored and never tire of change; they routinely interpret a disruption in the status quo as a challenge to grow.

The challenge for most organizations, it seems, is that they are paralyzed when confronted by equally compelling but seemingly contradictory demands. Either they freeze or they pursue one purely out of frustration with not being able to do both (or alternate between them). Thus, faced with the dilemma of promoting stability through shared mind-sets on the part of the leadership cadre while, at the same time, promoting change through divergent thinking, many will opt for the former until such time as it fails—and then they will turn 180 degrees to salute the flag of divergent thinking as they usher in an outsider as CEO.

Fortunately, several organizations have found a way to create experiences that renew and refresh leaders even as they strive to keep on a stable course. Toyota is a powerful example.

Toyota

At Toyota, much of the training that helps individuals learn and grow as leaders is embedded in initiatives and programs that have, on the surface at least, little to do with leadership. For example, according to Jeffrey Liker’s book about the company, supervisors and managers are routinely handed assignments that require them to reach out to others for information, resources, labor, and political support if they are to be successful.14 These tasks are not just obstacle courses that regulate movement up the ranks; they are opportunities to be coached or mentored and to experiment with new styles of managing and leading. Though referred to casually by some as a manifestation of Toyota’s deep “paranoia,” the discipline of continuous renewal applies to individuals, teams, technologies, products, and the organization as a whole.15 It’s a culture and a leadership philosophy dedicated to learning as a way to avoid the traps of success.

In fact, Toyota embeds four fundamental principles into its production system in a creative illustration of the power of renewal through experience. According to Steven Spear’s research at Toyota:16

• There is no substitute for direct observation. When it comes to diagnosing the ailments of a mechanical process, a business function, or a management practice, the ability to observe and document is essential. While not eschewing aggregate data, statistics, or the like, Toyota managers learn early on to watch people and processes rather than jump to conclusions. Doing this effectively demands discipline; it’s far too easy to jump to conclusions and, therefore, far too easy to overlook vital clues and surprises.

• Proposed changes should be structured as experiments. That is, disciplined approaches not only increase understanding but also make learning more efficient. Again, nothing is taken for granted. But employees at all levels must also have a facile understanding of what an experiment requires in the way of planning and controls.

• Workers and managers should experiment as frequently as possible. Small, simple experiments not only accelerate the pace of improvement and learning, but they also increase comfort and confidence with putting ideas at risk.

• Managers should coach, not fix. Leaders need to be open to learning, and they must encourage others to learn, too. As Spear observed, “Indeed, the more senior the manager, the less likely he was to be solving problems himself … The result of this unusual worker-manager relationship is a high degree of sophisticated problem-solving at all levels of the organization.”

No single one of the Toyota principles, by itself, seems remarkable. Taken together, however, they constitute an approach to learning from experience that is simple, adaptable, and inclusive. More important, it is a learning process that Toyota relies on, in order to keep ahead of the competition by means of rapid technological change, a continuously refined product development process, and work methods, that has successfully transferred throughout the world.

Now let’s look at another car company that also offers lessons in renewing.

Ford Motor Company’s Virtual Factory

One popular way to help seasoned veterans see the world differently is to pull them out of familiar surroundings. Off-sites in the woods and courses in the pastoral setting of a corporate university encourage everyone to breathe deeply and slip free from the tunnel vision of work where everything-is-so-urgent-youcan’t-stop-to-think. Or maybe not.

In 2001, Ford Motor Company founded and built the Virtual Factory and housed it in the basement of a nondescript brick building just off the crowded and perpetually under-repair Southfield Freeway in Dearborn Heights, Michigan. The “factory” resides in a single room, and the assembly operation consists of a network of personal computers arrayed in a large circle and partitioned into stages that mirror an assembly plant: chassis, body-inwhite, interior assembly, and final assembly. There are no cars in sight, except as subassembly cartoons that slowly march their way across the screen of each computer. Each computer represents a workstation—for example, where doors are hung on the naked chassis before painting. Simulated forklift trucks (dollies for carrying floppy disks that replenish the inventory of parts for each workstation), a tool crib, and an infirmary (a chair off to the side of the “factory floor”) complete the scene.

Since its inception, the factory has “graduated” over four thousand Ford employees to rave reviews. Everyone who passes through the virtual gates—whether they are assemblers and machine operators, first-level supervisors, engineers, or plant managers—walks away with a firsthand exposure to what the company hopes will be its factory of the future, based on the principles and practices of lean engineering and lean manufacturing. They don’t just play a video game; they rotate through roles: supervisor, line worker, skilled tradesman, union committeeman, and engineer. Pressure, noise, stress, and time constraints are re-created through elaborate but, according to participants, very realistic artifices, like simulated material shortages, physical accidents, machine breakdowns, surprise visits by the plant manager, and eight-hour shifts in a windowless environment. After-shift meetings focus on process improvement, as well as on team building and one-on-one coaching and feedback from trained observers. Veteran “factory rats” praise the simulation for its authenticity, but then marvel at the differences in their own behavior brought about by minor shifts in rules and roles. (Remember Penn and Teller’s approach to magic?)

The objective of the virtual factory is nothing less than to create “a paradigm shift in pedagogy that focuses on learning, not teaching,” according to Hossein Nivi, one of its principal designers. “Typical teaching techniques create disengaged students who are eager to escape an instructor reciting canned material. In the Virtual Factory, students learn by discovering the material through simulation and they develop the mental muscles needed to apply their discoveries.”

The core premise in the design of the factory is simple and familiar: production leaders have few, if any, opportunities to practice new skills or ways of working. Simulation provides the time and the methods to help participants renew themselves with challenging new practices, to think about alternative realities while enmeshed in a convincing simulation, and to refresh their enthusiasm for learning.

LOOKING BEYOND CONVENTIONAL BOUNDARIES

Although each organization described in the preceding section offers valuable examples and insights, none is a complete example of experience-based leader development.17 Yet by expanding the scope of exploration to the less conventional (“closed” or highly selective organizations as well as those that engage in activities that require secrecy and/or substantial bonds of trust), I found two organizations that do, in fact, offer a closer approximation of what I refer to as experience-based leader development. These two organizations rely heavily on experience—and on learning from experience—as a central part of their practice of growing leaders. In fact, they are organizations that must “grow their own” because of self-imposed restrictions on their ability to recruit leaders from the outside.

In the two organizations—the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints (the Mormons) and the Hells Angels motorcycle club—there is a strong need for leadership, particularly during periods of growth or attack from the outside. Likewise, in both religious organizations and outlaw gangs in general, members often operate over large territories, requiring them to both grow and populate an administrative structure of some sort.

Given that neither is unlikely to be in the leader development business—and that both are likely to be wary of outsiders—where do they go for leaders? How do they combat the tendency toward a weak leadership “gene pool”? What alternative approaches to leader development might they use?18

Before I begin to answer those questions, consider too that both organizations are large, durable, complex, multiunit, multinational entities that have experienced periods of rapid growth in the past three decades. Both have elected, for different reasons, to not go outside for leaders. Yet neither has suffered an obvious shortage of leaders. Both have closed borders and engage in selective recruitment of new members; and they rarely admit converts into the top leadership ranks. Yet neither suffers from a weak leadership gene pool. Most importantly for our purposes, both use crucible experiences as a central part of leader development. The most visible crucible for members and leaders of the Mormon church is the missionary experience: an eighteen-month to twoyear test of faith, identity, and leadership talent that also serves as the principal growth engine for church membership. For the Hells Angels, it takes the form of the motorcycle run: an event remarkable for its functional similarity to that of a missionary tour of duty, but also a period of time in which important leadership and learning lessons can be achieved.

A brief analysis of these organizationally instigated crucibles provides the final piece of the puzzle for what I have been calling experience-based leader development.

The Missionary Experience

With 12 million members, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints is well on its way to becoming a world religion. Especially notable is the fact that church membership doubled between 1985 and 2005 and has averaged 53 percent expansion per decade since 1945.19 The principal mechanism through which the Mormon church grows is proselytizing (or what members refer to as “proselyting”) largely through missionary work. In 2005, the Mormon church had over 52,000 men and women serving as missionaries in 162 countries. Since missions last two years for men and eighteen months for women, nearly 30,000 new missionaries must come forward each year.

Mission work—in the form of teaching, service, conversion, and baptizing—is critical to fulfillment of the members’ and the church’s spiritual obligation. But the mission is also fascinating from a sociological perspective. The mission is, at one and the same time, a critical organizational function, a rite of passage for young men and women (ages nineteen to twenty-six), and a leadership crucible. Missionary work grows the church and helps fulfill its earthly and spiritual objectives. It provides a capstone experience for young people—something they’ve been anticipating since childhood that cements them as adult members of the community. And it serves as a leadership crucible—a time of test or trial from which an individual emerges with a new or an altered sense of identity and from which also emanate the future leaders of the church.20

Mission work can easily be compared to a classic international assignment. Individuals are selected and assigned, prepared for the culture and the unique requirements of the job, deployed and managed while on-site, and renewed or reincorporated with new skills and perspectives. Yet, in order to capture the most from the experience, the Mormon process goes deeper on every level. Each phase emphasizes the acquisition of technical skills and learning skills. For example, before they leave for their particular posting, missionaries get intense training in language, culture, and pedagogical technique (the stages of conversion referred to as the commitment pattern). Those are the technical skills. In addition, missionaries are also steeped in methods for reading situations, judging the sincerity of someone on the journey to conversion, resolving conflicts and maintaining productive relationships with their missionary companions (with whom they live and work 24/7 for upwards of six months), and practicing in very practical terms the personal resilience necessary to withstand frequent rejection. Many missionaries keep journals during their time away and record their impressions, insights, and lessons learned so that they can revisit them later and gain insight through reflection.

Mission is a time for deploying skills and for experimenting, if only in small ways, with the words, gestures, images, and stories at the heart of the proselytizing process. It’s also a time for testing, exploring, and shaping one’s own identity. Indeed, it’s nearly impossible not to do so when, in the words of one missionary I spoke with: “You go to the door and for the ten-thousandth time you’re greeted with ‘Oh, you guys are crazy’ or ‘No thanks, I’m all set’ and the door slams in your face … The mission definitely teaches you how you can take a bad day and turn it into the most wonderful day of your life. It teaches you not to let the negative things that happen to you shape your decisions and your actions that day. You can use that negative and turn it into a positive.”

Successfully deploying a particular set of skills, whether you measure that success in the number of conversions or length of service, reinforces and extends the lessons learned in preparation and adds new ones. Support, in the form of senior companions like Major Rupp’s zone leader (described in chapter 2), enables missionaries to navigate through uncertain times and situations.

Return from the mission is a time of renewal for the individual and for the organization. Special parties are organized to welcome missionaries home. Families are counseled to give returning members time and space to collect themselves and to fit their new identity into an environment that will appear to them as having changed dramatically in their absence. Individuals find themselves displaying a newer, more mature and confident persona: someone both more worldly and more parochial (or dedicated to the church and the Mormon community). Alumni networks are formed among cohorts of returnees—many of whom will have gone through the Missionary Training Center together—and these serve not only to ease reentry but to periodically reunite and celebrate the experience.

As a result of the mission, then, the organization has new members and a fresh supply of dedicated individuals who represent the pool from which the next generation of lay leaders can be recruited. Let’s look now at how the Hells Angels accomplishes experiencebased leader development.

The Motorcycle Run

The Hells Angels began in 1948 in Oakland, California, and claims upwards of 2,500 members spread across 227 chapters in the United States and around the world. Alternately reviled and mythologized, the Hells Angels is perhaps best known for two things: its violent past—including murders, drug wars, and gang fights—and its longevity. This last point is fascinating because only a small handful of other groups involved in organized crime in the United States have remained viable entities for over fifty years. The Hells Angels has not only grown in number and complexity—there are, for example, dozens of branded products for sale, and the gang recently sued Walt Disney for copyright infringement—but it has also demonstrated remarkable stability and flexibility as an organization, despite the periodic arrest of large fractions of its leadership.

Like many network-based organizations, the Hells Angels maintains a strong core leadership and a relatively flat, multinodal (chapter) structure. This enables it to be both centralized, with a constitution and a clearly defined division of labor between the international organization and the chapters, and decentralized—for example, to protect itself from decapitation with the arrest and incarceration of top leaders.

Contrary to its media image as ruthlessly violent and anarchic, the Hells Angels shares in common with the Mormon church certain core attributes and practices. Leaders are rarely recruited from the outside, and candidates undergo both a careful screening process and critical crucible experiences. The most relevant crucible experiences involve organizing and successfully managing motorcycle runs. The run, according to retired Angels president Sonny Barger, “is a real show of power and solidarity when you’re an Angel. It’s being free and getting away from everything. Angels don’t go on runs looking for trouble; we go to ride our bikes and to have a good time together.”21

Organizing a run is no simple affair. Runs typically stretch hundreds of miles along public thoroughfares. The extraordinarily loud and deep rumble of dozens (occasionally hundreds) of unmuffled Harley-Davidson motorcycles can be heard for miles—no small source of delight to the riders. Though legal in most jurisdictions, runs nonetheless attract a great deal of attention from local law enforcement agencies and civic officials anxious to divert the event if possible. Moreover, runs invariably cross territorial boundaries between different clubs, many of which are hostile. Hence, negotiating a run is a challenge, and in some chapters it is a task rich with opportunities for learning about leadership.

A Hells Angels chapter president I interviewed leads a major California chapter, and though he refused to be identified publicly, he talked to me out of interest in the leadership topic. From his perspective, a run is a testing ground for future leaders: “The run organizer’s got to figure out the route and who we’re going to have to negotiate with to get it done. Sometimes it’s cops who’ve got it in for us and don’t want us near their town. So he’s got to figure out if it’s worth it to challenge them or whether to take a detour. If the guys in the chapter smell a little fear or whatever, they might push back and say, ‘Hell, let’s scare them!’ So, he’s gotta balance a lot of things. Keep in mind, it’s gotta be fun but it’s serious, too, because we got guys that are on parole so they can’t be outrageous. Unless they want to.”

A successful run requires imagination, negotiating skill, a surprise or two (e.g., an unusual camping spot or entertainment), and attention to history. Veteran members recall past runs and judge current ones accordingly. Run organizers benefit from building on legend and venturing to enable new ones. For example, one member discovered that bicycle paths could be used for legal passage when two towns refused to allow parade permits for a planned run.

Runs are organized several times a year in this leader’s chapter, and he allocated responsibility for organizing and managing them to men he considered “leadership material.” He explicitly counseled organizers to talk with veterans about what lessons they’d learned in previous runs and to prepare themselves for any of a host of contingencies, including accidents, brushes with the law, and inclement weather. Reflecting on his own experiences, the chapter president recalled, “It never occurred to me how organized we had to be in order to appear disorganized,” he said. “We have rules about lots of things—like when we carry guns and what time of day it’s allowable to shoot them. But you have to know town rules and laws, you have to be a lawyer to know whether crossing some county lines will violate a guy’s parole or something. It opened my eyes even more to what it takes to keep your freedom to do what you want.”

Every run, like every major Angels event (including the death of a member), is followed by a leadership meeting in which every detail is reviewed with a level of candor that journalist Hunter S. Thompson described forty years ago in the Nation as a “grouptherapy clinic.” Refusing to go into detail, the chapter president depicted these meetings to me as “an important part of a guy’s education. Who else is going to tell him that he fucked up but his family? We’re his family.”

Paradoxical as it may seem for an organization widely regarded as anarchic, the Hells Angels is exemplary in its use of critical experiences to grow leaders.

____________

Crucibles are transformative events through which people learn powerful lessons about what it takes to be a leader: how to adapt, how to engage others, how to live (not just to display) their integrity. And they learn a great deal about how they learn and how they can keep on learning. Crucibles are complex, demanding, and daunting, but they are frequent and they are free. The challenge, as I’ve tried to portray it in this chapter, is in how organizations can leverage and even foster the experiences that help aspiring leaders become adept or even outstanding leaders.

Fortunately, the power of experience is not lost on organizations that have set for themselves the task of growing leaders. But few organizations carry the task through all phases of the learning cycle. Some excel at preparing or deploying but have yet to extend the process to renewal. Others strive to renew but have yet to connect those efforts to preparing. And then some—indeed, the majority, I would argue—deploy potential leaders into assignments and geographies pregnant with the potential to learn from experience, but largely fail to prepare them and almost always neglect to renew them.

A brief side trip in my quest for an experience-based approach to leader development provided glimpses at a solution that more mainstream businesses and governments might consider applying. As we saw, the Mormons and the Hells Angels demonstrate how it is possible to craft or to convert core activities to serve as practice fields for leaders. In both cases (though in very different ways), the Mormons and the Hells Angels engage in elaborate preparation before sending would-be leaders out into the field. They teach technical skills, certainly, but as important are the learning skills: the rules of the road, the watch-outs for oncoming trouble, and the ways to preserve one’s identity and sense of wholeness while engaging with others.

The Mormons and the Hells Angels also provide a supporting infrastructure while members are in the midst of a crucible. There are senior, seasoned companions and supervisors who know when to say no. Coach or mentor, the role is not just a job. It is a statement of commitment to the individuals in need and to the mission of the organization, as well.

Finally, both the Mormons and the Hells Angels recognize the need for renewal in both individuals and the organization. They organize to accomplish both stability and change by investing in crucible events. Crucibles foster a new generation of leaders, enable each organization to replenish and even to expand its ranks, and provide a selective membrane that screens new ideas and new technologies before they enter the organization.

Five criteria for effective experience-based leader development can be extracted from GE, Toyota, Ford, Accenture, Deloitte, MIT, the Hells Angels and the Mormon church:

• Helping individuals clarify their aspirations and values will strengthen their ability to mine experience for insight.

• Leaders need to learn technique and judgment, and organizations can foster both.

• Feedback needs to be fast, honest, and immediately incorporated into changed behavior.

• Practice needs to be encouraged as a lifelong pursuit.

• Adaptive capacity is essential for individual leaders and for the organizations that want to grow them.

Now it is time, in the next chapter, to merge the two models at the heart of experience-based leader development. For individuals: the model of expert performance with a Personal Learning Strategy at its core; for organizations: prepare, deploy, renew.