SEVEN

From Market-Driven to Market-Driving

Incrementalism is innovation’s worst enemy.

CEOs DEMAND, EXHORT, AND BEG their organizations to innovate. In particular, CEOs stress the value of radical or discontinuous innovation because it helps a company outpace its competition and thus deliver sustained growth. Yet innovation often inches along rather than leaps forward in established firms. Why? Because companies revere the market-driven process that currently dominates business.

Current practice intimates that careful market research of the customers’ needs and creative development of differentiated products or services for a well-defined segment will lead to success. Various strong companies such as Nestlé, P&G, and Unilever effectively employ this market-driven approach. However, successful pioneers like Amazon, The Body Shop, CNN, IKEA, Starbucks, and Swatch have created new markets and revolutionized existing industries through radical business innovation. In essence, they have driven the market; they are market-driving.

Consider Aravind Eye Hospital of Southern India.1 In 1976, a fifty-eight-year-old retired eye surgeon, Dr. G. Venkataswamy, devised a plan to serve the 20 million residents of India who were blind from cataracts. Venkataswamy envisioned marketing cataract surgery, a relatively straightforward operation, like McDonald’s hamburgers. Hospitals in India typically fell into one of two categories—private, state-of-the-art hospitals that served the small, wealthy segment of the population or charitable, outmoded, overcrowded hospitals that served the poor, vast majority. Moreover, a large number of the poor, who reside in the countryside, could not access these urban hospitals.

To realize his vision of eyesight for the blind regardless of their ability to pay, Venkataswamy founded hospitals in southern India that serve both the rich, who pay for the modern cataract surgery, and the poor, who receive almost identical service for free. The sales, advertising, and promotion of Aravind Eye Hospital focus on attracting free rather than paying patients. For example, the sales force has annual targets for the number of free patients admitted; weekly “sales meetings” monitor individual performance toward these targets. Aravind’s sophisticated salespeople scour the Indian countryside looking for poor patients within their assigned territories and then transport them to the hospital at no cost.

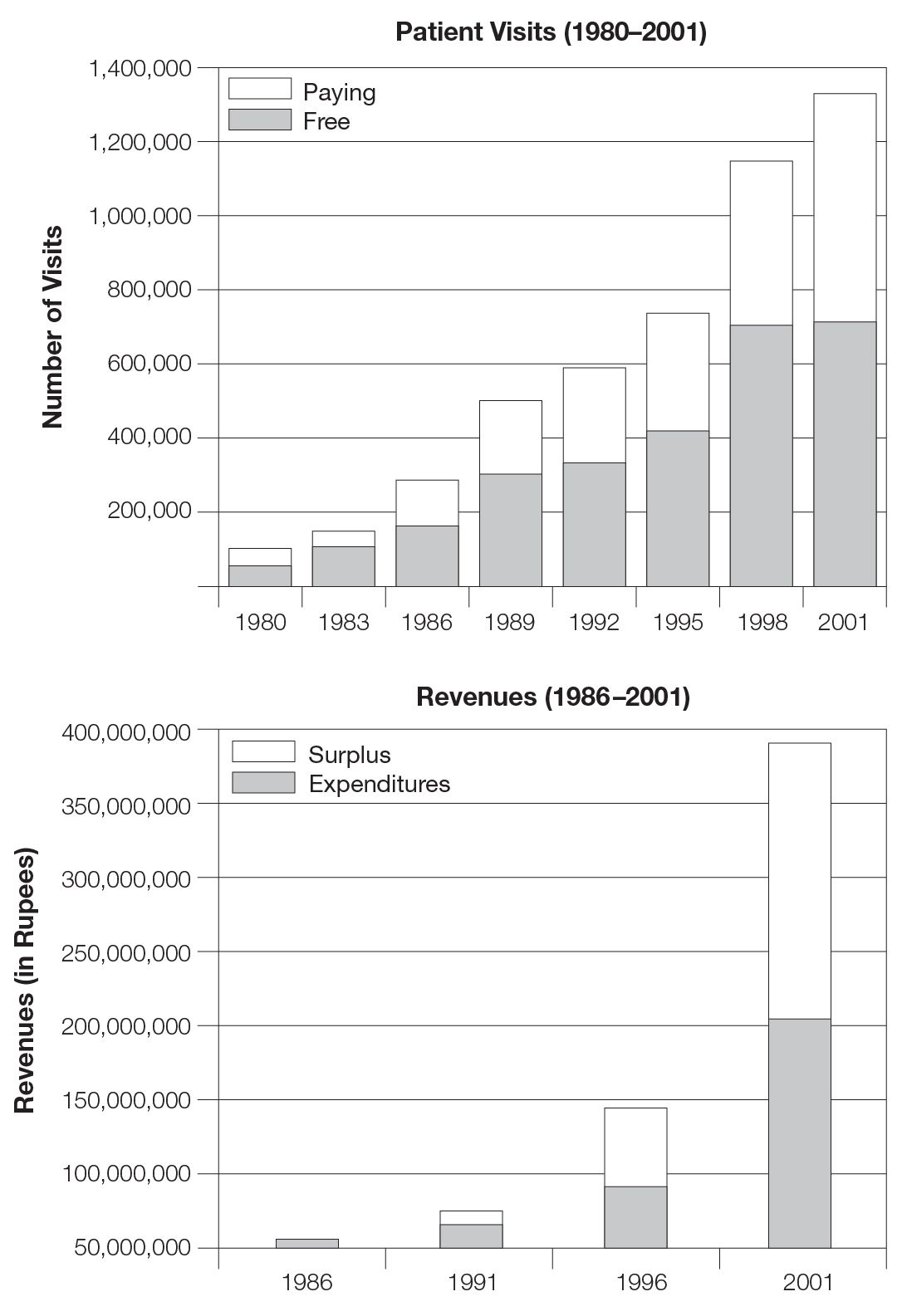

By focusing on eye care and routinizing procedures, Aravind’s surgeons are so productive that this nonprofit organization has a gross margin of 50 percent despite the fact that more than 65 percent of the patients served do not pay. Unlike most nonprofit organizations in the developing world, it does not depend on donations and attempts to maximize the number of free patients served (see figure 7-1 ). In 2002, Aravind Eye Hospital served 1.4 million patients and performed 200,000 eye surgeries.

Aravind Eye Hospital’s market-driving approach resembles those of Amazon, The Body Shop, Club Med, Dell, Hennes and Mauritz, IKEA, Sony, Swatch, Tetra Pak, Virgin, and Wal-Mart. These market-driving firms did not use traditional market research to devise their status quo–busting strategies. Market research seldom leads to such breakthrough innovations.2 As Henry Ford observed, “If I’d listened to customers, I’d have given them a faster horse.”

Growth of Aravind Eye Hospital

The inspiration for the radical business ideas of market-driving firms came from visionaries such as Venkataswamy, Anita Roddick of The Body Shop, and Richard Branson of Virgin, who saw the world differently and whose vision addressed deep-seated, latent, or emerging customer needs. Rather than focusing on obtaining market share in existing markets, these market drivers created new markets or redefined the category in such a fundamental way that competitors were rendered obsolete (for example, none of the top ten discounters of 1962, the year Wal-Mart was born, are in business today).3 Ultimately, these firms revolutionized their industries by “driving” their markets, rules and all.

These firms are market drivers for three reasons:

- They trigger industry breakpoints, or what Andy Grove of Intel calls “strategic inflexion points,” which change the fundamentals of the industry through radical business innovation.

- Visionary rather than traditional market research inspires their radical business concept.

- Rather than learn from existing customers, they often teach potential customers to consume their drastically different value proposition.

The Market-Driving Firm

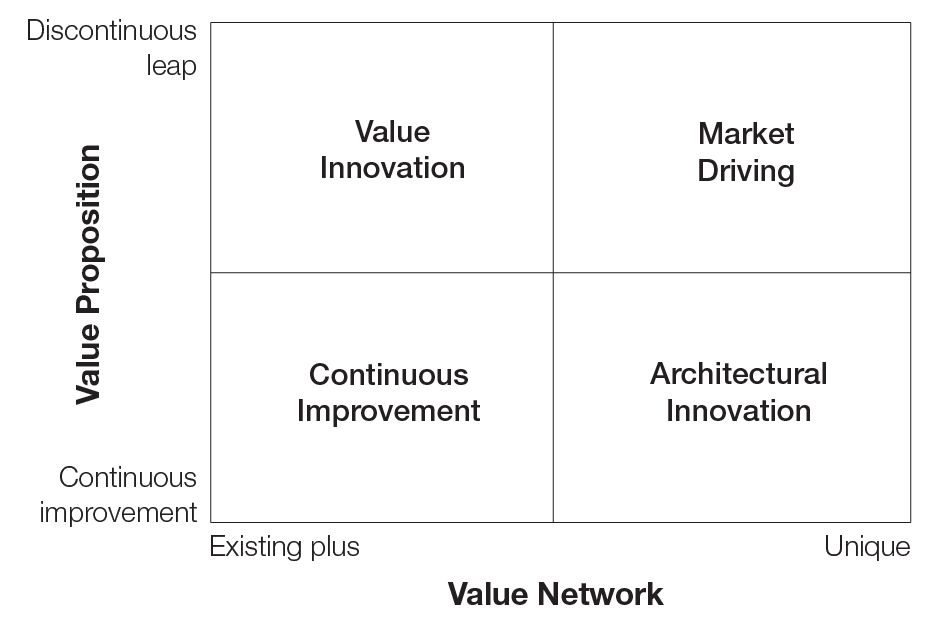

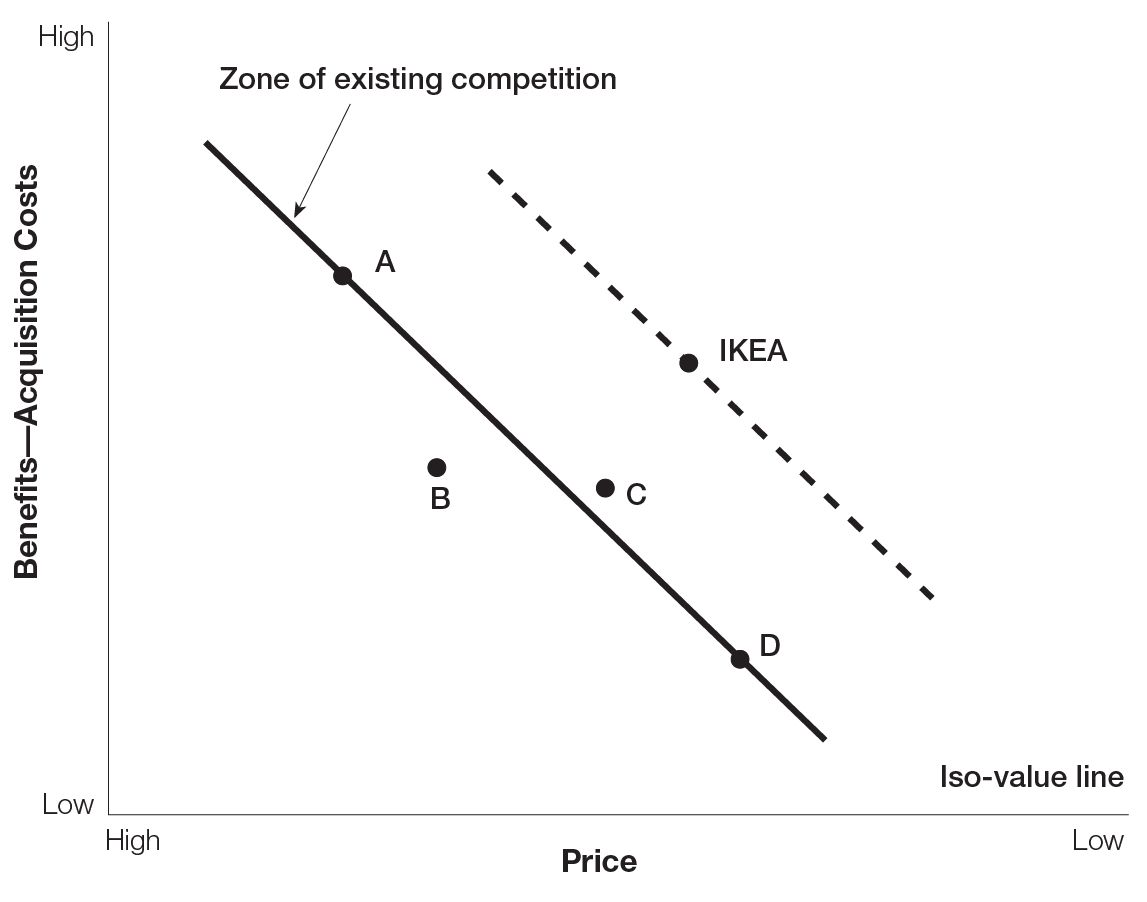

The success of market-driving firms stands on radical innovation in two dimensions—a discontinuous leap in the value proposition and the rapid configuration of a unique value network (see figure 7-2). Value proposition, as defined in chapter 2, refers to the combination of benefits and price offered to customers.

Market Driving IKEA Style

Ingvar Kamprad opened his furniture retailer IKEA in the 1950s; it now employs 70,000 people, operates in thirty countries, and generates a turnover of 11 billion euros. Rather than target middle-aged people in city centers as traditional full-service high-end furniture stores did, IKEA focused on young people and young families. To these customers, IKEA offered clean Scandinavian design and image, tremendous assortment, immediate delivery, a pleasant shopping atmosphere, and low prices in exchange for self-service, self-assembly, and self-transportation of purchases. As figure 7-3 indicates, rather than straddle the existing industry iso-value line, market-driving firms such as IKEA deliver a discontinuous leap in customer value.

Types of Strategic Innovation

The transformation in customer value may involve either breakthrough technology or breakthrough marketing. The success of companies such as IKEA is less about new technology than about aggressively exploiting existing technology to serve the customer in an unconventional manner. The key to the success of market-driving firms is that they create and deliver a leap in benefits, while reducing the sacrifices and compromises that customers make to receive those benefits.4 They create a product or service experience that vastly exceeds customer expectations and existing alternatives, thereby elevating the industry landscape.

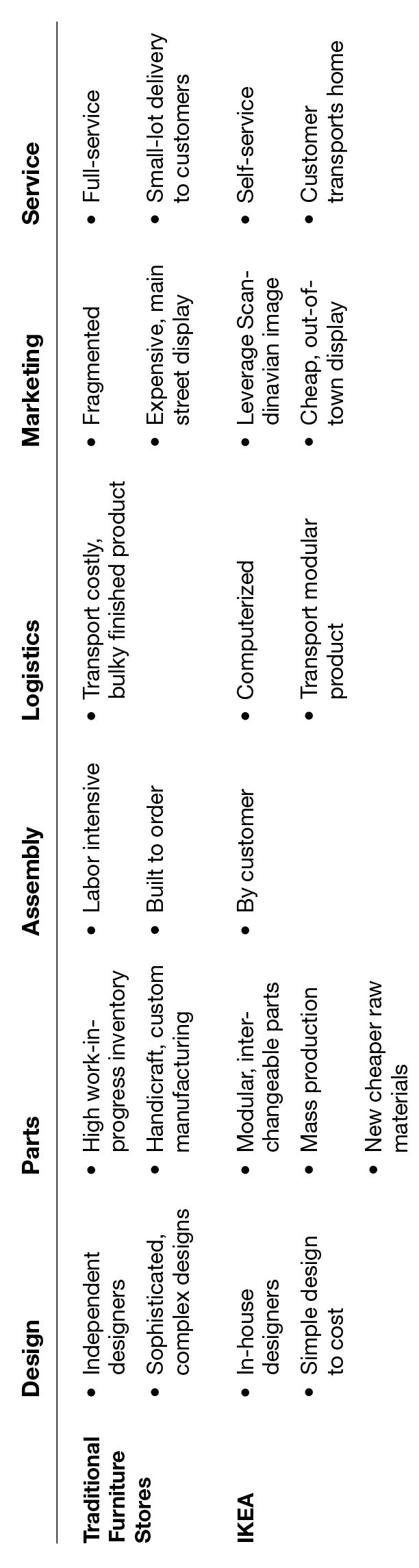

Value network refers to the configuration of activities required to create, produce, and deliver the value proposition to the customer. IKEA could not deliver discontinuous value by simply improving upon the business model of traditional furniture stores beleaguered by expensive independent designers, high work-in-progress inventory, labor-intensive handicraft manufacturing, transportation and inventory of finished goods, fragmented marketing, costly retail locations, elaborate displays, and expensive delivery to the consumer. IKEA had to reconfigure the model radically. CEO Anders Dahlvig observes, “Most others were copying what everyone else was doing and tried to do it a little better here and there. We did it totally different.”5

IKEA’s Leap in Customer Value

As table 7-1 reveals, IKEA’s unique value network uses costconscious in-house design, interchangeable parts, high volume component manufacturing, parts inventory (rather than more expensive finished product inventory), extensive computerization of logistics, its natural Scandinavian image, relatively inexpensive peripheral locations, and simple display facilities, leaving final transportation and assembly to the consumer.6 To copy IKEA’s value proposition profitably, firms in the traditional channel would need to dismantle the existing value network while migrating to an IKEA-type network.

IKEA’s Unique Value Network

Source: Adapted from Xavier Gilbert, “Achieving Exceptional Competitiveness” (presentation at IMO, Lausanne, Switzerland, 1999).

Because the value proposition is visible in the marketplace while the value network is harder to discern, competitors often miss the importance of the latter. Without a unique value network, existing players can fairly rapidly copy any advantage gained from a discontinuous leap in the value proposition. Therefore, market-driving firms that change the rules of the game are those that innovate on both dimensions of figure 7-2. The unique value network creates a more sustainable advantage. Would-be competitors need time to acquire the competencies as well as assemble the intraorganizational and interorganizational players necessary for replicating that unique value architecture.

Four Orientations to the Marketplace

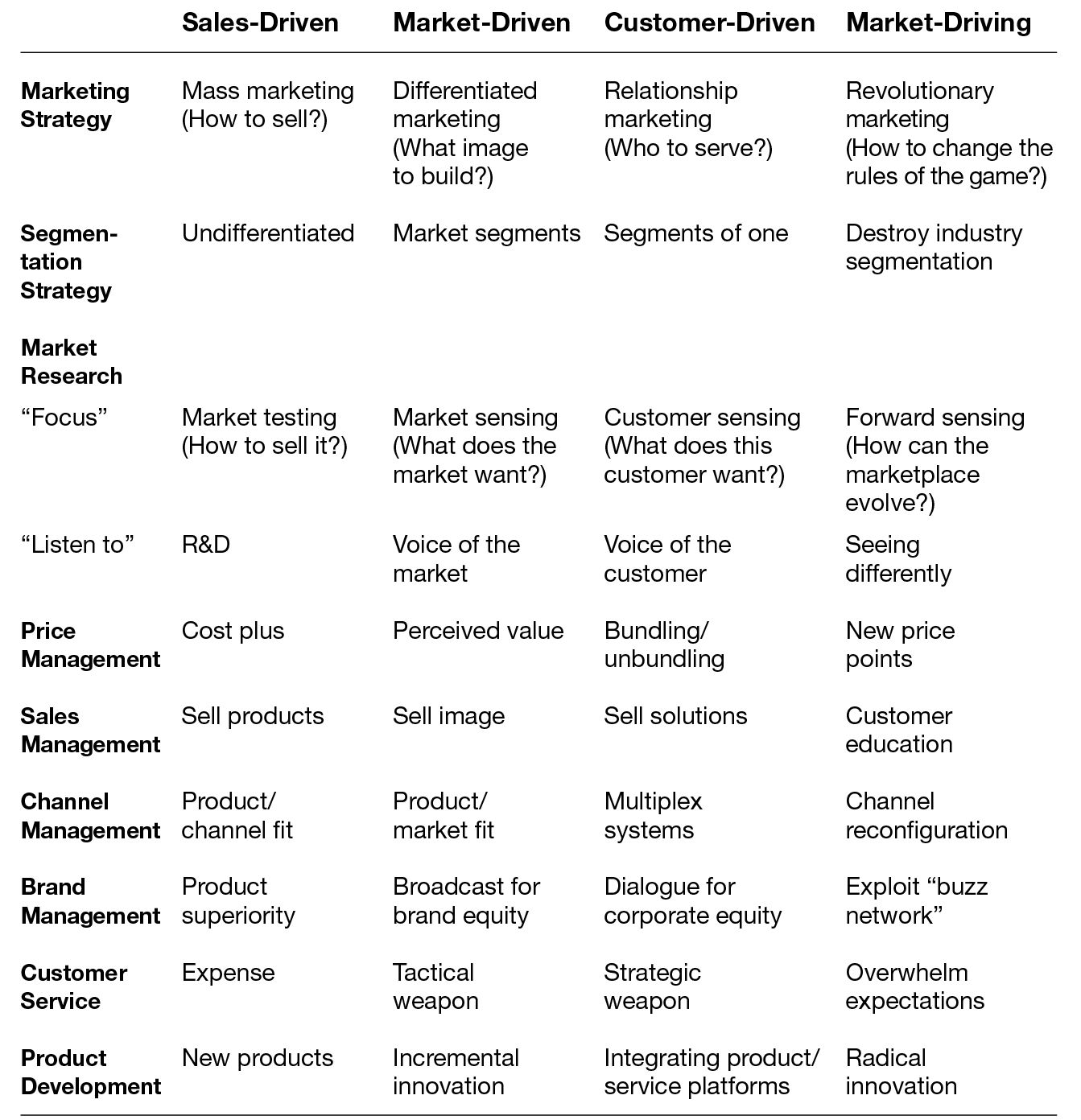

In addition to market-driving, there are three other corporate orientations toward the marketplace: sales-driven, market-driven, and customer-driven.

A sales-driven organization views marketing as a tool to sell whatever it produces. In such companies (often public utilities, monopolies, and some large manufacturers), marketing and selling are interchangeable.

Market-driven companies develop appropriate products and the desired image for their target segments based on market research. Most successful consumer packaged goods companies such as L’Oreal fall in this category.

Customer-driven companies target “segments of one” and conduct “relationship marketing” to deliver customized value configurations. The Swiss private banking industry, which serves high-net-worth individuals, typifies such customer-driven firms.

Table 7-2 summarizes the key distinctions among these four orientations. All four categories represent ideals, however; no large organization adopts a single orientation through all business units.

Four Orientations to the Marketplace

How Market-Driving Firms Seize Advantage

Based on an in-depth study of twenty-five market-driving firms, this chapter concentrates not only on how market-driving firms compete, but also on the transformational marketing strategies that undergird these companies.7 The following sections detail how market-driving companies differ from more traditional companies on the various dimensions of marketing strategy.

Lead by Vision Rather Than by Market Research

Consumers and organizational buyers (such as purchasing agents) are excellent at motivating and evaluating incremental innovation. However, customers cannot usually visualize the revolutionary products, concepts, or technologies themselves. Swatch offers an excellent case study. The Swatch models that received the highest intention-to-purchase rating in consumer research looked like traditional watches, but they ultimately generated very few sales. The more radically different Swatch models that rated the least likely to sell were subsequently the bestsellers. Had Swatch followed its market research, it would have missed a runaway success. Similarly, customers did not clamor for Starbucks coffee, CNN, or overnight small package delivery prior to their introduction.

Market-driving firms instead coalesce around visionaries who see opportunity where others do not—an opportunity to fill latent, unmet needs or to offer an unprecedented level of customer value. In market-driving firms, generation and development of “the idea” is a combination of serendipity, inexperience, and persistence. For example, Starbucks was founded in 1983 after Howard Schultz, charmed by the Italian coffee culture of Verona and Milan, promised to bring it to the United States.

Frequently, the visionaries’ relative inexperience with the industry meant they had not yet been inoculated with that industry’s received wisdom. Nike’s Bill Bowerman was a college track coach, Club Med’s Gerard Blitz was a diamond cutter, and Ingvar Kamprad of IKEA began his entrepreneurial career selling fish. Often, these visionaries persisted in the face of many failures and rejections to realize their dream. For example, Fred Smith of FedEx developed the guaranteed overnight delivery idea in a business school term paper as a junior at Yale. He received a C for the paper because the instructor was not convinced of its practicality.8

Some market-driving firms spent years muddling through refining their vision before perfecting their strategies. Sam Walton’s initial attempts at opening stores were underwhelming. David Glass, who later became CEO of Wal-Mart but was at that time employed by a competing store, reportedly opined after checking out the first Wal-Mart Discount City Store, “Those guys will never make it.” Sam Walton continued to tinker with the formula until he got it right. Few of these visionaries expected that their business idea would achieve the level of success that was ultimately attained. As Hasso Plattner, the cofounder of SAP, observed: “When people ask how we planned all this, we answer ‘We didn’t. It just happened.’”9

Because they are changing the rules of the game and facing many obstacles on the way to success, market-driving companies recruit and select people who subscribe to the values of the organization. There is often an attempt to attract those with little experience in the industry, individuals who have not been infused with the industry’s conventional wisdom about why the market-driving idea is doomed to fail. Such employees are motivated strongly by their belief that they are on a mission, not simply by money. A compelling vision enthusiastically articulated by a charismatic leader turns these employees into crusaders.

- Sam Walton wanted to “give the world an opportunity to see what it’s like to save and have a better lifestyle, a better life for all.” This mission, paired with the belief that Wal-Mart stores would “lower the cost of living for everyone, not just America,” energized his employees.

- Ninety percent of The Body Shop franchisees are women who have no formal business training but are instead chosen on the basis of personality tests, home visits, and attitudes toward the environment and people. They are motivated by founder Anita Roddick’s idea that they can make a difference in people’s lives and in the world through The Body Shop.

- In the early days at FedEx, there were couriers who pawned their watches to pay for gasoline.

Such historic, sometimes mythic, stories become part of the organizational culture of most market-driving firms.

Redraw Industry Segmentation

By attracting their customers from a variety of previously defined market segments, a new market coalesces around the market-driving firm’s product-service offering and marketing strategy. This creates havoc in the industry by destroying the industry segmentation that existed prior to the market driver’s entry and replacing it with a new set of segments reflecting the new, altered landscape.

- Aravind Eye Hospital did not accept the normal segmentation between rich and poor patients.

- Southwest Airlines destroyed the segmentation between ground transportation and airlines, attracting many who would not otherwise have flown at all.

- Swatch, with its cheap and fashionable watches, bridged the chasm between the segments for cheap, utilitarian watches and expensive, fashionable ones.

- Wal-Mart demonstrated that small rural towns could support huge discount stores, which previously had been located only in large urban areas.

- While existing software vendors concentrated on developing different software packages for different departments (for example, manufacturing, sales, human resources), SAP destroyed these distinctions by developing enterprise software that could integrate and run the entire business.

Create New Price Points for Value

To deliver a leap in customer value, market-driving firms establish new industry price points for the quality or service levels they deliver. Swatch, Aravind Eye Hospital, Southwest Airlines, and Charles Schwab all set prices much lower than those previously available for similar products. This puts existing competitors under tremendous pressure. The competitors must make dramatic changes in operations and product lines to survive, but they cannot swiftly meet the challenge because they cannot quickly and successfully reproduce the innovative value network that enables the lower price point. Continental learned this the hard way when it tried to compete against Southwest Airlines with “Continental Lite.”

- When Southwest Airlines enters a new city, it prices against ground transportation, not just against existing air service, so that its prices fall at least 60 percent below competitive airfares. For example, early in its history, Southwest charged $15 for a trip from Dallas to San Antonio when Braniff, the next most inexpensive competitor, was charging $62. A shareholder asked the CEO, “Could you not raise the price two or three dollars?” The response: “We are not competing against other airlines but ground transportation.”

- Swatch adopted a simple introductory pricing strategy—$40 in United States, 50 CHF in Switzerland, 60 DM in Germany, and 7,000 yen in Japan—and held those prices for the first ten years despite high demand.

Whereas the trend is toward higher performance at lower price points, there are market-driving firms who have established elevated price points that are higher than typical in an industry. CNN, Starbucks, and FedEx set prices considerably above what customers had been paying. Inducing the buyer to pay these higher prices requires that these market-driving firms have a value proposition that is substantially more compelling than the available alternatives.

Educate Customers for Sales Growth

Given the radical new concept, the sales task for market-driving firms is not to sell but rather to educate the customer on the existence of, and how to consume, their radical value propositions (see figure 7-4).

- Aravind Eye Hospital must continuously educate its “free” patients, who are predominantly illiterate, that their vision can in fact be restored and that the necessary surgery is available to them free of charge.

- IKEA had to teach consumers the benefits of transporting furniture components home for self-assembly instead of buying it preassembled and delivered. When IKEA entered Switzerland, they ran advertisements that joked about the Swiss unwillingness to transport and assemble furniture, even for lower prices. The advertisements poked fun at the self-delivery and self-assembly aspects, saying “That is a stupid thing” and “You can’t do that to the Swiss.”

Reconfigure Channels

In almost every market-driving firm, channel reconfiguration initiated the architectural innovation that yielded a unique business system. Consider the following:

- FedEx transports packages using its own planes via a “hub and spokes” air freight system rather than “point-to-point” commercial flights used by competitors such as Emery. FedEx is twice as likely as Emery to deliver on time.

- Benetton subcontracts simple, nonessential tasks and performs only crucial quality-maintenance tasks such as dyeing. By knitting products before rather than after dyeing, Benetton can respond faster to sales data on color preferences than its competitors.

- Wal-Mart insists that P&G and other suppliers rationalize product lines, adopt everyday low prices, eliminate wholesalers, present one invoice per company, and establish electronic links with Wal-Mart stores, all to eliminate considerable costs in the network.

Exploit the “Buzz Network” for Brand Attachment

Market-driving firms often rely more on the “buzz network” to convey their message. Since these firms offer a leap in customer value, many customers will notify others of their “amazing new find.” Reporters in trade publications and the popular press want to be the first to cover the radical new innovation. Early adopters and opinion leaders generate the excitement and brand cachet that market-driving firms strive to maintain. Consequently, market drivers spend less money on traditional advertising; the advertising-to-sales ratio pales compared to that of their established competitors.

- Southwest Airlines boasts, “We have a lot of ambassadors out there, our Customers.” Every year representatives from dozens of cities beg Southwest to launch services in their area.

- A 1958 thirteen-page Life magazine photo spread on Club Med drew many more customers than capacity. In 1962, twelve years after the first village was built, it turned away more than a 100,000 applicants as it could only accommodate 70,000 members.

- Nike did not run a single national television advertisement until it reached $1 billion in sales. It used “word-of-foot advertising” by getting the best athletes to wear its products.

- Virgin’s Richard Branson generates constant free press through his hot air balloon expeditions, highly public media wars against the established players (such as having all planes painted with a banner against the proposed BA-AA merger), and appearing publicly in “drag.”

Overwhelm Customer Expectations

Market-driving firms surpass customer expectations by delivering service at levels far above what consumers expect for the market driver’s price.

- The poor patients of Aravind Eye Hospital never expected to regain their sight, since surgery was out of their geographical, economic, and psychological grasp.

- Since other discounters lower customer expectations by providing poor service, Wal-Mart seems to provide great value. Whenever it rains in Houston, an umbrella-wielding service rep walks customers to their cars at Wal-Mart’s discount store and Sam’s Club, a warehouse club that operates on slim 10 percent gross margins. No wonder a typical Wal-Mart customer visits Wal-Mart thirty-two times a year compared to a Kmart customer who shops only fifteen times per year there.

- Twelve times between 1987 and 1993, low-priced Southwest won the unofficial “triple crown” of commercial aviation—fewest customer complaints, fewest delays, and fewest mishandled bags—an unprecedented feat. CEO Herb Kelleher observed, “It’s easy to offer great service at a high cost. It’s easy to offer lousy service at low cost. What’s tough is offering great service at low cost, and that is what our goal is.”10

Barriers to Market Driving in Incumbent Firms

Large incumbents typically launch incremental innovations rather than radical ones. Since the success of market-driving firms depends on radical innovation in value and network, market drivers are typically newcomers whose founders grew frustrated by their staid employers:

- Ben Franklin franchise headquarters rejected the “big stores in small towns” idea of Sam Walton, one of Ben Franklin’s franchisees.

- Many major shoe manufacturers rejected the athletic shoe concept—a shoe with lighter soles and better support, traction, and stability that would be comfortable for athletes—that Nike eventually implemented.

- Ex-IBM employees formed SAP after IBM Germany refused their request to develop enterprise software for ICI.

Why do successful incumbents flounder in combining radical innovation in value proposition and value network? Primarily because their well-established new business development processes cannot accommodate the following four features of market-driving ideas.

Market-Driving Ideas Overturn Industry Assumptions

Market-driving ideas are maverick and serendipitous in nature. Nobody can predict where such an idea will originate or who will generate it. Since most companies organize for efficiency, they react negatively to surprises.11 Furthermore, individuals often feel pressure to hide market-driving ideas since they rebel against the prevailing industry and incumbent wisdom. The vast industry experience of established firms therefore becomes a barrier to driving markets. People cannot easily unlearn conventional wisdom, however irrelevant.12 Current market leaders often discard maverick ideas that clash with prevailing industry intelligence. An obsession with history—or even the present—can prevent a firm from shaping its future.

Consider Linotype-Hell, a German company that invented Linotype printing presses in 1886. The “hot-type” Linotype system was widely used for printing books, magazines, and newspapers until the 1970s. Although the company had dominated every advance in publishing technology, the digital age of software-and scanner-based printing blindsided it. As Linotype managers clung to their “hot-type” mind-set, the company’s stock fell from a record high of 970 DM in May 1990 to 56 DM in July 1996. In 1997, Heidelberger Druckmaschinen, AG, acquired Linotype-Hell.

Market-Driving Ideas Are Risky

Market-driving ideas involve high risk. For every successful radical innovation in value proposition and value network, probably hundreds fail. An entrepreneur chasing a market-driving dream has delimited downside financial risk as he generally invests enormous effort but limited capital. However, if the idea succeeds, then he has unlimited upside potential to make a vast personal fortune. In most organizations, the originator of a successful market-driving idea may receive a nice bonus or promotion (limited upside potential), but a public failure may destroy his or her career (substantial downside potential). When the high failure rate of radical innovation is combined with the risk/reward ratio in most large organizations, pursuing market-driving ideas is irrational for employees.

Market-Driving Ideas Consistently Lose to Incremental Innovation

The new business development process in most firms tends to disfavor, and therefore squelch, innovative breakthroughs that might create new markets. When competing for attention, resources, and approval, incrementally innovative projects tend to edge out more radical ones. In most established firms, the new product development and new business development processes favor the triable, reversible, divisible, tangible, and familiar. Projects must clearly benefit current customers, move in the organization’s direction, and correspond with R&D investments, corporate image management, sales training, and distribution—all of which rarely typify radically innovative offerings.

Established firms select new business development opportunities based on technological feasibility and potential market size. However, in the early developmental stages, no one can definitely know which technology will succeed, with what capabilities, for which markets. The technological and operational problems seem insurmountable, often with no obvious market. Expected applications dissolve and unforeseen opportunities emerge while the firm experiments.

For example, Nutrasweet’s two initial applications—replacing saccharin and artificially sweetening breakfast cereals—fizzled because saccharin users actually preferred saccharin’s aftertaste and Nutrasweetened breakfast cereal hit technical and regulatory obstacles. Instead, Nutrasweet found a sizzling market in dissatisfied sugar users.13

Market-Driving Ideas Cannibalize Existing Business

Finally, established firms often perceive that they have too much invested in the status quo to risk destroying the existing industry and market. The greater the threat of cannibalization, the more intense is the resistance to market-driving ideas.

- IBM focused too long on mainframes because PCs required a different distribution system, had lower margins, and lacked after-sales service opportunities.

- General Motors and Ford responded to the popularity of minivans too slowly because minivans jeopardized their station wagon market.

- Bausch & Lomb ignored the more comfortable disposable soft lens market because of its robust permanent soft lens and solution businesses.

The Market-Driving Transformation Process

Although new entrepreneurial firms can single-mindedly pursue a make-or-break market-driving project, most established firms have too many obligations to chase only radical market-driving ventures. They cannot pursue radical business innovation without improving the existing business and devoting much of their efforts to market-driven activities, such as incremental innovation and traditional market research. Nevertheless, top management must find room and resources for radical innovation or the market leader risks being leap-frogged and deposed by upstart market drivers.

Firms need to be ambidextrous, capable of simultaneously managing incremental as well as radical innovation.14 However, this is difficult to do since radical and incremental innovation are different animals requiring their own supporting cultures (see table 7-3). As Bernard Charles, president of Dassault Systemes, argues:

Incremental Versus Radical Innovation

| Incremental | Radical | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Low | High |

| Focus | Cost or feature improvements in existing products | Development of new products/ services and functionalities |

| Business Model | Known—detailed plan can be developed | Uncertain—plan evolves as learn by doing |

| Value Network | Utilizes existing industry value network—competence enhancing | Requires new value network—competence destroying |

| Project Evolution | Linear and continuous | Sporadic and discontinuous |

| Process | Formal, phase-gate model to allow high control | Informal, flexible model to allow serendipity |

| Resources | Standard resource allocation process | Creative acquisition of resources |

| Project Speed | Being first is important | Important to time when market is “ready” |

| Customer Interaction | Test with, and learn from, key customers | Speculate with fringe customers |

Source: Adapted from http://www.1000ventures.com/business_guide.

Company cultures that are more risk averse ultimately drive innovation through a practice of continuous improvement and steady progress, and as a consequence are more consistent in meeting their goals. Cultures that are less risk averse tend to target major gains in a single, bold step. They do not always succeed, but when they do, the impact is significant.15

Managers in established firms must choose projects to balance incremental and radical innovation in the companies’ portfolios so that both promising incremental projects and radical projects obtain time, money, and resources. An established firm that wishes to engage in market-driving faces two challenges: it must have the vision and environment to generate breakthrough ideas and it must have the capital, fortitude, and risk tolerance to persevere and give the radical idea a fair chance to succeed.

The first challenge involves developing the ability to “see differently.” Since radical concepts often spring from a single person’s imagination, the firm must create an environment where individual creativity flourishes. Without the ability to see differently, the firm cannot change the rules of the game. The second challenge is to successfully market the unique concept, which requires a team effort. Without the ability to implement a market-driving concept, the firm will join the ranks of companies that failed to capitalize on their inventions, such as Xerox with personal computers and EMI with scanner technology.

Unlike incremental innovation, where innovating is an ongoing process, the development of market-driving ideas is more project-based. Perhaps what Somerset Maugham observed about writing novels applies here: “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately no one knows what they are.” Yet certain practices can help established firms increase their probability of driving market innovations. As Viacom’s chairman and CEO Sumner Redstone pointed out, “Size is not a barrier to creativity; it’s bad management.”16 Firms aspiring to market-driving innovations should adopt the following processes and practices.

Develop Processes to Identify Hidden Entrepreneurs

In any large company, many employees have radical business ideas. Top management must formalize processes to encourage out-of-the-box thinking and discover these hidden entrepreneurs within the firm. For example, in 1992, NEC invited its employees to submit proposals for their own start-up companies to give new business ideas space to develop outside the corporate bureaucracy. 17 Entitled “Venture Promotion and Entrepreneur Search Program,” it generated 146 proposals.

Shirota, a fifty-six-year-old career NEC employee, submitted one of the selected proposals. His business idea was to develop and market a software program that would provide a high-tech design tool for Japan’s kimono makers. By scanning the customer’s photograph into a computer and then graphically superimposing kimonos, the customers can “try on” different kimonos without actually changing outfits. The company, Kainoatec, was launched in 1995 with NEC providing 54 percent of the 13 million yen start-up capital and with Shirota and a colleague, Koterazawa, each chipping in 3 million yen. Since its launch, Kainoatec has developed similar software for the eyeglass industry so that customers can try on spectacles without having to remove their own eyeglasses. The venture generated profits of nearly 5 million yen in its first year and has increased sales and profits every year since then.

The in-house entrepreneur program has become an annual event at NEC. More than six hundred new business ideas have been generated. To maximize the number of proposals, the annual invitation is widely publicized to all employees of NEC and its subsidiaries. Furthermore, initial proposals are limited to presenting only an overview of the new business concept. Later, as proposals move through various selection steps, projected sales, profits, and investment information are gathered through detailed business plans. As Shirota, now president of Kainoatec, observes, the program helps discover hidden entrepreneurs among the Japanese salarymen who are waiting for someone to tap them on the shoulder and give them a chance.

Allow Space for Serendipity

Serendipity has played a role in the development of many radical new ideas. To allow for serendipity, 3M researchers are encouraged to spend up to 15 percent of their time on a research project of their choice. This ensures that problem-driven research does not preclude all curiosity-driven research. 3M’s famous Post-it notes were invented when an associate was attempting to develop a better bookmark for his hymn book. Similarly, one of Searle’s research scientists discovered the artificial sweetener Nutrasweet while looking for a possible treatment for ulcers. As Schumpeter observed: “History is a record of ‘effects,’ the vast majority of which nobody intended to create.” Unfortunately, reengineering efforts in most firms have eliminated much of the slack within which serendipity thrives.

Select and Match Employees for Creativity

To generate new ideas, Nissan Design International deliberately promotes “creative abrasion” by hiring a diverse group of people and putting them to work in contrasting pairs (for example, balancing nerds with hippies). Employees are encouraged to display color charts of their “personalysis” to help managers do the mixing.

In an industry known for both creativity and massive excess, Alain Levy, chairman and CEO of EMI, has similarly found success by matching skills and attitude using a two-headed structure which he refers to as “my creative head and his No.” For example, Matt Serletic sniffs out new talent as head of Virgin Music, and Roy Lott keeps Serletic financially in check.18

For implementation of creative ideas, Henry Ford looked toward inexperienced employees: “It is not easy to get away from tradition. That is why all our new operations are always directed by men who have no previous knowledge of the subject and therefore have not had the chance to get on really familiar terms with the impossible.”19 In many market leaders, however, rounds of testing and interviews do more to reinforce conformity than to assemble a collection of individuals with diverse capabilities and perspectives. Creativity demands team diversity on function, age, gender, education, culture, mind-set, and life experiences.

Offer Multiple Channels for New Idea Approval

Even firms with a history of prior market-driving activity find it difficult to keep the fires of iconoclastic creativity stoked. Today’s successful market driver must beware of ossifying into the cautious, market-driven behemoth of tomorrow. In any large firm many frustrated potential entrepreneurs can be found who have ideas as yet unveiled. In most organizations, approval of a new business idea requires several “yes” votes up the hierarchy while a single “no” can kill it; and a market-driving idea will almost certainly get a “no” somewhere in the process.

To surface promising new initiatives, 3M has numerous channels that employees can use to secure approval and support for a project if their immediate superior rejects it. Providing alternative routes to authorization alters the dynamic to one where a project garnering a single “yes” and several “no’s” can still proceed.

Establish Competitive Teams and “Skunk Works”

Early in development, no one can unconditionally forecast the winning technology or final market. Assuming that the marketplace will select the winner, Motorola encourages its wireless divisions to compete against each other. IBM had about half a dozen parallel development teams for the PC. When focusing on a new technology, Sharp often maintains small R&D projects on alternative technologies.

In an established firm, a radical new concept will typically either fall outside the current business definition and target markets of the firm (for example, Nutrasweet for Searle) or threaten to destroy the firm’s existing business (for example, IBM’s PC). In addition, market-driving projects, by definition, require a unique business system and therefore lack synergy with the firm’s existing value network. When people pursue market-driving ideas within the existing structure, other priorities often hinder a speedy fruition.

To overcome organizational resistance and inertia, firms can set up “skunk works,” physically and organizationally independent, self-contained entities with dedicated members. Skunk works harness and concentrate the entrepreneurial zeal and urgency of members, and protect the fledgling project from bureaucrats who would otherwise kill it.

Apple, 3M, IBM, Raychem, DuPont, Ericsson, General Electric, Xerox, and AT&T all use skunk works in order to nurture the soul of a small, entrepreneurial outfit within their large corporations. Some companies have recently soured on skunk works, mostly likely because they used skunk works inappropriately, for incremental innovation and adjacencies. Skunk works work best for unleashing “killer apps,” not “feature creeps.”

Cannibalize Your Own Products

Established market leaders rarely pursue projects that might undermine their core business. For example, Kodak’s desire to ensure that its new digital business does not encroach on its traditional film business has slowed its progress in digital imaging. But as Pablo Picasso once observed, “Every act of creation is first of all an act of destruction.”

Market-driving explicitly encourages cannibalization, based on the belief that since some firm will cannibalize a company’s core business, it might as well do it itself. When Sony introduces a major new product, three teams are created: the first team tinkers with minor improvements, the second seeks major improvements, while the third explores ways to make that new product obsolete. At Hewlett-Packard, which fosters competition among its divisions, products less than two years old account for 60 percent of orders.

Market-driving retailers such as Starbucks and Sam’s Clubs of the United States, Sweden’s Hennes and Mauritz, and Italy’s Benetton strategically cannibalize their own stores to some extent by building new outlets close to existing, successful locations, thereby leaving few vacant spaces for competitors to exploit. They believe in keeping the cannibals in the family.

Encourage Experimentation and Tolerate Mistakes

Developing an experimenting organization that seeks creative solutions requires a tolerance for mistakes. Firms must probe and learn in the marketplace, improving with each successive generation. The first Wal-Mart store was horrible but Sam Walton improved the format over time by trying different ideas and watching customer reactions. Similarly, Nike’s original shoe wasn’t very good but the company kept learning and improving the technology. As Ingvar Kamprad of IKEA observed, “Only while sleeping one makes no mistakes. The fear of making mistakes is the root of bureaucracy and the enemy of all evolution.”20

In the United States, the focus on daily stock price, quarterly results, and Wall Street analysts tends to severely punish missteps. This is another hurdle that large, publicly traded market leaders must manage to effectively cultivate market-driving activity. The company must carve out a sheltered area where the risk-taking associated with experimenting can be tolerated and where there is room for the inevitable failures that will ensue. These potential failures are the price the firm must pay to cultivate market driving. As Thomas Edison was quoted as saying, “I have not failed, I have simply found 10,000 ways that do not work.”

There must, however, be some rules regarding failures. David Pottruck, CEO and president of Charles Schwab, articulated the following three rules: (1) Don’t put the company at risk. By limiting the enormity of possible failure, one ensures that employees bet the horse, not the farm. (2) Take reasonable precautions against failure. (3) Learn something from it.21 As Philips’ CEO, Gerard Kleisterlee, observed, “a learning culture means allowing mistakes to be made but making sure they are not repeated. ”22

Putting It All Together: Sony’s Market-Driving Culture

Over time, even successful market-driving firms change, as they should, into market-driven firms. The history of innovation consists of patterns in which bursts of breakthrough innovation that reshape an industry are interspersed by flows of less dramatic incremental improvements and refinements. Once the radical innovation phase is over, incremental innovation to improve the existing offering and business system becomes the primary challenge.

Furthermore, competitors ultimately emerge with competitive, or even superior, value propositions and business systems modeled after the “new” market leader. At this stage, market-driving firms like Tetra Pak must search for their next market-driving innovation. However, as the successful market driver transforms into an established market leader, it faces all the same obstacles to motivating market-driving strategies that the former market leaders faced. As Picasso noted: “Success is dangerous. One begins to copy oneself. It is more dangerous than copying others. It leads to sterility.”

With age and size, firms tend to become increasingly bureaucratized, routinized, and risk averse. To date, very few firms—except perhaps Sony—have consistently launched a series of successful market-driving ideas.23 Sony has been a powerhouse in developing and launching innovative products that have created new markets and businesses, such as the transistor radio, Walkman, 3.5-inch diskette, and audio compact disc. “New products create new markets” is a guiding credo at Sony. Sony claims that their strongest assets are employees who combine dreams of creating new products or markets with the passion and enthusiasm to execute them.

Sony practices several principles that large, established companies should adopt to become more market-driving. Sony leaves room for experimentation, tolerates mistakes, cannibalizes its own, encourages competitive teams, and offers multiple channels for approval of new ideas. It also nurtures and rewards individual creativity, as illustrated by the following story.

In 1980, three teams in two departments were working in parallel to develop a 10× improvement to the conventional 5.25-inch “floppy” diskette. Initially, each team was a single individual with a distinct vision of the product concept. The first individual envisioned it as a more compact floppy, the second individual visualized it as a 3.5-inch plastic-encased disk, and the third individual, who was in a different department, was working on a 2-inch diskette with high rotation speed. At this stage, it was unclear whether any of these would deliver a product that could be marketed successfully.

After three months, the first team had encountered several technical problems while the second team, led by twenty-eight-year-old Kamoto, had developed a promising prototype (an early version of the 3.5-inch plastic-encased diskette that is the world standard today). Since they belonged to the same department, the first team was disbanded with the former members redirected to other projects, including a few who were assigned to the second team. The head of the department asked the former leader of the first team to author and present a paper on the 3.5-inch diskette at an upcoming Japanese technical conference. It was explained to Kamoto that while all the internal recognition at Sony for the invention of the 3.5-inch diskette would go to Kamoto, it was important to keep the former leader of the first team motivated.

The 3.5-inch diskette, unveiled at the Chicago industry show in 1981, piqued Apple’s interest. In 1983, Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple Computer, adopted the new diskette for the Macintosh, but demanded assurances that the product would be substantially improved within one year. The enhanced system would be doublesided rather than single-sided, incorporate an automatic inject and eject system, and still reduce power consumption, height of the disk drive, and price by 50 percent. Despite these improvements, the product was still ignored by most of the larger IBMcompatible world, and was adopted by only two major customers, Apple and Hewlett-Packard. In 1987, Kamoto was transferred to sales and marketing despite having no experience in these functions. It was thought that only he, having invented the 3.5-inch diskette, had the passion to make it a worldwide standard. It replaced the 5.25-inch floppy diskette as the standard format for storing data by personal computer users.

In 1991, Sony put Kamoto in charge of improving its languishing personal computer internal hard drive business, hoping that he would do for hard drives what he had done for the 3.5-inch diskette. Unfortunately, despite his best efforts, the venture was an expensive failure and Kamoto was asked to close down the operation. Given this highly visible failure, Kamoto thought his career at Sony was effectively over. Sony, however, recognized that he was motivated by his enthusiasm to contribute to the company and accepted the failure as a learning experience. Following the hard drive fiasco, Sony gave Kamoto the responsibility for managing another data storage device, the magnetic tape drive. Under his charge, Sony’s worldwide market share for magnetic tape drives increased from 3 to 25 percent over three years.

While Kamoto and the 3.5-inch diskette were moving from one success to another, the leader of the third team, Ken Kutaragi, was struggling. His design for the 2-inch diskette was completed in 1982, the year after the 3.5-inch diskette. Kutaragi’s diskette delivered excellent performance, but its architecture required significant changes in the associated hardware. As a result, Sony was the only company to adopt it for their laptop, “Produce.” Unfortunately, the laptop did not succeed and Kutaragi had to search for other applications for the 2-inch diskette.

The diskette found its next home in Sony’s new still camera, “Mavica,” which also failed, despite high expectations. Kutaragi, doggedly persisting in the face of continuing failure, then approached Nintendo in the hope of persuading them to use the 2-inch diskette with their video game software. When Nintendo signed a contract with Sony for the 2-inch diskette, Kutaragi thought he had finally found the killer application for his invention. But three years later, Nintendo canceled the contract without ever using the product.

A disappointed Kutaragi approached Sony’s leadership with a proposal to develop their own line of video games using CD-ROMs. Kutaragi convinced Sony that his three years of discussion with Nintendo had given him a deep understanding of the video-game business and insights into Nintendo’s strengths and weaknesses. With assistance from Sony’s business strategy group, PlayStation video games were developed and launched in 1994 as a competitor to Nintendo. Since its launch, Sony has sold more than 90 million PlayStations and controls 70 percent of the global video-game market of $10 to 15 billion.24 The game unit that Sony first deemed tangential to its operations now generates a third of the company’s profits and embodies Sony’s vision of integrating games and consumer electronics.

Conclusion

This book began with Peter Drucker’s observation, “The business enterprise has two and only two basic functions: Marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs.” Yet large business enterprises in particular struggle with both marketing and innovation.

Marketing must become more innovative—but it must do so in a way that will help the organization to make discontinuous leaps. It must provide more business model and business concept innovation by finding underserved markets, developing radically new value propositions, and creating new delivery mechanisms. Marketing cannot rely solely on R&D for new product development. The following box provides a market-driving checklist.

Market-Driving Checklist

Market-Driving Mind-Set

- Does our top management continuously reinforce the need for market-driving ideas?

- Do we actively seek to cannibalize our own products?

- Is the pursuit of competing emerging technologies permitted?

- Are new ideas routinely imported from the outside?

- Are time and resources allocated for curiosity-driven explorations?

Market-Driving Culture

- Do we tolerate failures when people are attempting something really new?

- Are processes in place to capture learning from failures?

- Are people encouraged to share their failures publicly?

- Do we constrain innovation through too much respect for hierarchy?

- Are organizational rules and norms enforced too rigidly?

- Do we tolerate mavericks and allow space for champions to flourish?

Market-Driving People

- Do we hire people who will increase the genetic pool of our company?

- Do we mix people on teams to generate creative abrasion?

- Are novices included on important projects to question assumptions?

- Do we think our people are entrepreneurial?

- Are exceptional innovation achievements and efforts recognized and rewarded?

Market-Driving Processes

- Do we allow for long payback horizons for innovation projects?

- Do we accept alternative routes to obtain funding and approval for market-driving ideas?

- Do we have processes that move ideas from the bottom to the top without obstruction?

- Do we run competitions to generate radical new concepts?

- Do we ensure that radical ideas do not lose resources to incremental ideas?

In addition, innovation must be linked more tightly to marketing. History is replete with innovative new products and business ideas that have failed to succeed because of poor marketing. In incremental innovation, marketing’s role is clear: provide customer feedback and market research as well as manage the market launch process. For radical innovation and market-driving ideas, the role of marketing is more obtuse and often contrary to deep-seated marketing beliefs. The challenge in these cases is to find a segment of the market for whom the radical value proposition is attractive. This initial “innovator” segment is then used as the beachhead from which to improve the firm’s attack on the more mainstream markets.

From the CEO’s perspective, lack of time, resources, or money are poor excuses for a failure to be innovative in large companies. As Scott McNealy, Sun Microsystem’s cofounder, noted, “there’s never been a successful well-funded startup. If you have too much money, you’re not going to find a new and different and more efficient and effective way. You’re just going to try and overpower the current players with the same strategy. You can’t win a sailboat race if you’re behind by tacking behind the boat in front of you.”25

The CEO’s mandate is clear. As Francisco Gonzalez, technophile chairman of Spain’s Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA, puts it, “We’ve got one clear premise: we want entrepreneurs more than administrators.”26 But hiring entrepreneurs is easier than giving them the space to be creative. For example, while most media companies struggle to manage the interface between creative thinking and the corporate profit center, HBO prides itself on having an edgy creative outfit within a vast corporation. It does it by creating a small boutique-like identity and granting creative independence within a tightly controlled operation. As an HBO creative noted, “It’s an amazing place to work. Once they have hired the right people, they give you the liberty to do what you want.” The result, directors and writers coming knocking at their door rather than the other way round, as at most media companies.27

Perhaps there is no better way to end this chapter than to note that at market-driving firms, the sense of radical innovation starts at the top. Sony’s President, Kunitake Ando, declares, “Sony’s mission is to make our own products obsolete. Otherwise somebody else will do it.”28 With this attitude, everyone in the company, including marketers, must always be aware that a customer is someone who has not yet found a better alternative.