C H A P T E R 21

Understanding Linux Users and File Permissions

Most modern operating systems work with user accounts to grant people access to the system, and Ubuntu is no exception. You might not have noticed this—if during installation or when you personalized your system you selected the option to allow automatic logins, you are taken directly to your desktop when you boot your PC, thus masking the fact that a user is actually logging into the system.

So, whether you’re aware of it or not, you always have a user account inside Ubuntu. Your user account will have a defined set of attributes that will distinguish it from other user accounts: for example, a name and a Home folder. But it also will be a member of a group. Being a member of certain groups allows access to portions of the system that would be otherwise hidden, because groups can enable permissions to access and manipulate files on your hard disks. And, since all configuration in Ubuntu is stored in files (see Chapter 10), those permissions will allow it to change the system itself.

Understanding User and Group Accounts

We’ve already stated that to interact with Ubuntu you need a user account. However, there’s more to the story than that. For example, there are situations in which you might need more than one user account. Either in the office or at home there may be more than one person that uses the computer, and you surely will want to keep your personal configuration and data separate from theirs. That’s when the need for additional user accounts arises. This section will explain what a user account is, how to create it, and how to work with groups.

Users and Groups

Each person who wishes to log into Ubuntu must have a user account. This will define what that user can and cannot do on the system, with specific reference to files and folders. Because Ubuntu is effectively one large file system (even hardware devices are files; see Chapter 10), user permissions lie at the heart of controlling the entire system. They can limit which user has access to which hardware and software, and therefore control access to various PC functions.

Each user also belongs to a group. Groups have the same style of permissions as individual users. File or folder access can be denied or granted to a user, depending on that person’s group membership.

![]() Note As in real life, a group can have many members and can be based around various interests. In a business environment, this might mean that groups are created for members of the accounting department and the human resources department. By changing the permissions on files created by the group members, each group can have files that only the group members can access (although, as always, anyone with superuser powers can access all files).

Note As in real life, a group can have many members and can be based around various interests. In a business environment, this might mean that groups are created for members of the accounting department and the human resources department. By changing the permissions on files created by the group members, each group can have files that only the group members can access (although, as always, anyone with superuser powers can access all files).

On a default Ubuntu system with just a handful of users, the group concept might seem somewhat redundant. However, the concept of groups is fundamental to the way Ubuntu works and cannot be avoided. Even if you don’t use groups, Ubuntu still requires your user account to be part of one.

In addition to actual human users, the Ubuntu system has its own set of user and group accounts. Various programs that access hardware resources or particular sets of files are part of these groups. Setting up system users and groups in this way makes the system more secure and easier to administer.

Root User

On most Linux systems, the root user has power over the entire system. Root can examine any file and configure any piece of hardware. Root typically belongs to its own unique group, also called root.

Ubuntu is different from most Linux distributions in that the root account isn’t used by default. Instead, certain users—including the one set up during installation can “borrow” root-like, or super user, powers by simply typing their login password. This is done by preceding commands with sudo or gksu at the command-line prompt, or as needed when using GUI programs that affect system settings. For some programs you need to click an Unlock button to gain superuser powers. If you wish, you can activate the root user account on your system for administration purposes. To activate the root account, use the following command in a terminal window (see Appendix A for details on issuing commands in a terminal window):

Sudo passwd root

After typing your own login password, you’ll be invited to define a password for the root user. Because of its power, the root user can cause a lot of accidental damage, so by default Ubuntu prevents you from logging in as root. Instead, you can switch to being the root user temporarily from an ordinary user account by using the Switch From option in the Shutdown menu. This will leave your session open while letting you open an additional session as any user (e.g., root).

You will be prompted for the root password and then given root powers for as long as you need. When you’ve finished, log out and return to your ordinary user account.

![]() Tip You can tell when you’re logged in as the root user because in the Me menu your name is “root.” This should be seen as a warning that you now have unrestricted control over the system, so be careful what you type, and double-check everything before pressing Enter!

Tip You can tell when you’re logged in as the root user because in the Me menu your name is “root.” This should be seen as a warning that you now have unrestricted control over the system, so be careful what you type, and double-check everything before pressing Enter!

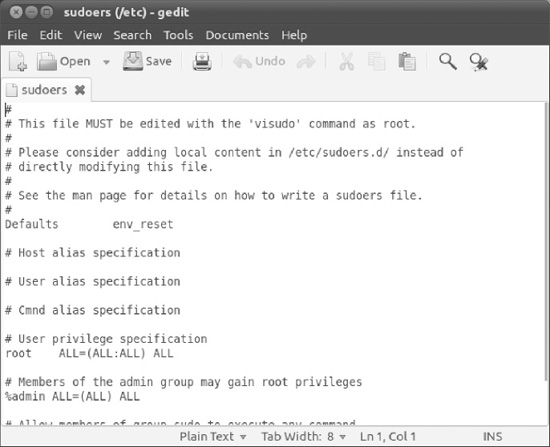

If you enable the root password in the name of security, it might be a sensible precaution to then disable sudo, thus preventing nonadmin users from playing with things they shouldn’t. To do this, you’ll need to edit the file /etc/sudoers. There will be a line (shown in Figure 21-1) that reads as follows:

%admin ALL=(ALL) ALL

Comment this out with a # sign and save the file (see Figure 21-1). This, of course, will all need to be done using root privileges, so use gksudo gedit in the Run a command dialog box (accessible by pressing Alt+F2) to launch the text editor, and then navigate to and open the file. Also make sure you’ve set up the root password, as shown earlier, before you do this.

Figure 21-1. Be very cautious when editing these files.

Users and File Permissions

The concepts of users and permissions are as important to Ubuntu as the idea of a central and all-encompassing file system. In fact, the two are implicitly linked.

When initially installing Linux, you should have created at least one user account. By now, this will have formed the day-to-day login that you use to access Linux and run programs.

Although you might not realize it, as a user you also belong to a group. In fact, every user on the system belongs to a group. Under Ubuntu, ordinary users belong to a group based on their usernames (under other versions of Linux, you might find that you belong to a group called users).

![]() Note Groups are yet another reminder of Ubuntu’s UNIX origins. UNIX is often used on huge computer systems with hundreds or thousands of users. Putting each user into a group makes the system administrator’s job a lot easier. When controlling system resources, the administrator can control groups of users rather than hundreds of individual users. On most home user PCs, the concept of groups is a little redundant because there’s typically a single user, or at most two or three. However, the concept of groups is central to the way that Linux handles files.

Note Groups are yet another reminder of Ubuntu’s UNIX origins. UNIX is often used on huge computer systems with hundreds or thousands of users. Putting each user into a group makes the system administrator’s job a lot easier. When controlling system resources, the administrator can control groups of users rather than hundreds of individual users. On most home user PCs, the concept of groups is a little redundant because there’s typically a single user, or at most two or three. However, the concept of groups is central to the way that Linux handles files.

A standard user account under Ubuntu is typically limited in what it can do. As a standard user, you can save files to your own private area of the disk, located in the /home directory, but usually nowhere else. You can move around the file system, but some directories are strictly out of bounds. In a similar way, some files are read-only, so you cannot save changes to them. All of this is enforced using file permissions.

Every file and directory is owned by a user. In addition, files and directories have three separate settings that indicate who within the Linux system can read them, who can write to them, and, if the files in question are runnable (usually programs or scripts), who can run (execute) them. In the case of directories, it’s also possible to set who can browse them, as well as who can write files to them. If you try to access a file or directory for which you don’t have permission, you’ll be turned away with an “access denied” error message.

Root vs. Sudo

Most versions of Linux have two types of user accounts: standard and root. Standard users are those who can run programs on the system but are limited in what they can do. The root user has the complete run of the system, and as such, is often referred to as the superuser. The root user can access and/or delete whatever files it wants. It can configure hardware, change settings, and so on.

Most versions of Linux create a user account called root and let users log in as root to perform system maintenance. However, for practical as well as security reasons, most of the time the user should be logged in as a standard user.

Ubuntu is different in that it doesn’t allow login as the root user. Instead, it allows certain users, including the one created during installation, to temporarily adopt root-like powers. You will already have encountered this when configuring hardware. As you’ve seen, all you need to do is type your password when prompted in order to administer the system.

This way of working is referred to as sudo, which is short for superuser do. Most applications that require root privileges will ask you for your password if you are a sudoer (i.e., a standard user with permission to act as root in specific circumstances). Other applications might not require that you have root privileges, but you might want to open them as root from time to time. Good examples of this are Nautilus and gedit—maybe you want to completely remove a deleted user’s Home folder and you can’t do that as a standard user. For this you use Gksudo, which is a graphical front end to the sudo command (which will let you adopt root powers at the shell prompt—simply preface any command with sudo and type your password when prompted in order to run it with root privileges). If you open the Run a command dialog box (press Alt+F2) and type gksudo Nautilus, you will be able to browse the file system as root. Or, if you want to edit a file to which only root has write privileges, run gksudo gedit. Ubuntu remembers when you last used sudo, too, so it won’t annoy you by asking you again for your password within 15 minutes of its first use.

In some ways, the sudo system is arguably slightly less secure than using a standard root account. But it’s also a lot simpler. It reduces the chance of serious errors too. Any command or tweak that can cause damage will invariably require administrative powers, and therefore requires you to type your password or preface the command with gksudo or sudo. This serves as a warning and prevents mistakes.

UIDs and GIDs

Although we talk of user and group names, these are provided only for the benefit of humans. Internally, Ubuntu uses a numerical system to identify users and groups. These are referred to as user IDs (UIDs) and group IDs (GIDs), respectively.

Under Ubuntu, all the GID and UID numbers below 1,000 are reserved for the system. This means that the first nonroot user account created during installation will probably be given a UID of 1000. In addition, any new groups created after installation are numbered from 1,000. The first user you add has a UID of 1000 and a GID of 1000, the second user a UID of 1001, and so on.

![]() Note UID and GID information isn’t important during everyday use, and most commands used to administer users, groups, and file permissions understand the human-readable names. However, knowing about UIDs and GIDs can prove useful when you’re undertaking more complicated system administration, such as setting up a restricted system for children or scripting.

Note UID and GID information isn’t important during everyday use, and most commands used to administer users, groups, and file permissions understand the human-readable names. However, knowing about UIDs and GIDs can prove useful when you’re undertaking more complicated system administration, such as setting up a restricted system for children or scripting.

Adding and Deleting Users and Groups

The easiest and quickest way to add a new user or group is to use the Users and Groups tool under the System Administration menu. Of course, you can also perform these tasks through the command line.

Adding and Deleting Users

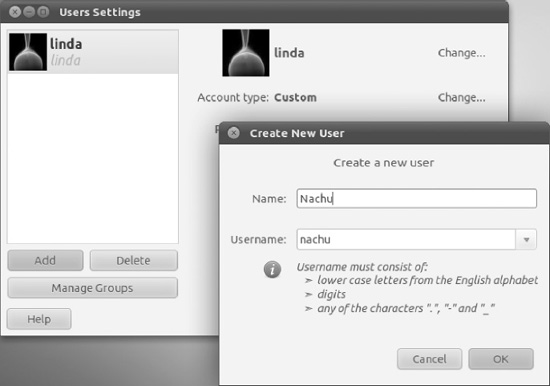

To add a new user, choose the Users and Groups command from the Application menu. Next, click Add. In the authentication window, supply your password and click Authenticate. You’ll see the Create New User dialog box, as shown in Figure 21-2.

Figure 21-2. Adding new users and groups is easy with the Users and Groups program.

Complete the account creation wizard as follows:

Create a new user: As during initial installation (see Chapter 5), you’re invited to enter a username as well as a real name. The username is how the user is identified to the system, while the real name is how the user will be identified to other users. By default they are set to the same. Press OK when done.

Changing user password for: You can set the user’s password by hand or let the system generate a random password for you. In either case, make sure to remember the password to give it to the person that will use the user account. You can also select the option to let the user to log into his session without entering the password. Press OK when finished.

Once the user has been created, you can set additional settings by selecting the user from the list and clicking the various options at the left of the User Settings window. The user account is disabled by default, so you should click the Enable Account button before using it.

Account type: You can select the profile you want the user to have: Administrator, Desktop User, or Custom. Users with the Administrator profile can use

sudoorgksuto administer the system. Although desktop users can’t use these commands, they do have access to most other system resources. For most users, the Desktop User profile is a good choice. You cannot select the Custom profile for a user account, but if you manually change its privileges (more about this shortly), this profile is selected automatically.Password: An initial password for the user is required, but you can change it any time you want with the Users and Groups tool (as long as you have the required privileges). You can enter it in the text box (and confirm it below) or let the system generate a random password from letters and numbers, but this may be harder for the user to remember.

If you click the Advanced Settings button, more options will be available, as follows:

Contact Information: Here you can enter contact information for the user. This is not obligatory.

User Privileges: The settings on this tab offer much more control over what a user can and cannot do on the system. Here you can prevent users from using certain hardware, such as the 3D capabilities of graphics cards, or modems. You can also control whether the user is able to administer the system. Simply put a check alongside any relevant boxes.

Advanced: Here you can alter additional settings, if you wish, relating to the technical setup of the account on the system. If you’re not sure about these parameters, it’s best to leave the default settings alone. You can disable the account from here, and it will no longer be available for login. You might like to change the main group for the user as well. By default, the user will belong to a newly created group based on the user’s own username. For example, if you add the user

john, he will be added to the groupjohn. This private group approach enforces a more stringent policy regarding personal file access. Alternatively, you could create a single group and assign several users to that group for file-sharing purposes. We’ll discuss adding and removing groups in the next section.

![]() Caution Many groups are listed in the Main Group drop-down list. Nearly all of these relate to the way the Linux operating system works and can be ignored (you can see the list of groups in Table 21-1). You should never delete any of these groups or add new users to them. This may make the system unstable and/or insecure.

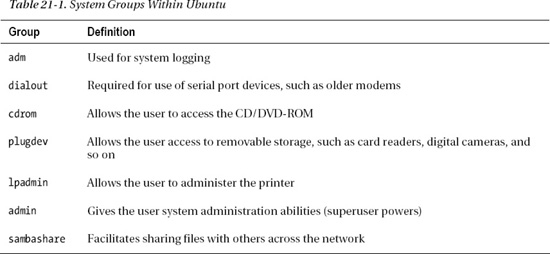

Caution Many groups are listed in the Main Group drop-down list. Nearly all of these relate to the way the Linux operating system works and can be ignored (you can see the list of groups in Table 21-1). You should never delete any of these groups or add new users to them. This may make the system unstable and/or insecure.

Deleting a user is simply a matter of highlighting the username in the list within the main Users and Groups window and clicking the Delete button. Note that you can choose to either delete the user’s Home folder or to keep the files. You might want to access the files yourself and make a backup of them before completely removing the Home folder.

Creating and Deleting Groups

Adding a group is simply a matter of clicking the Manage Groups button in the Users and Groups program window. After clicking the Add button, you’ll be prompted to give the group a name. The GID will be filled in for you automatically, but you could choose a different number if you have good reason to do so. (Remember to use a number above 1,000 to keep in line with the way Ubuntu operates.)

It isn’t essential that you add users to the group then and there, but a list of users is provided at the bottom of the dialog box. Put a check alongside any user to grant that user access to your group.

![]() Note Bear in mind that users can be members of more than one group, although all users have a main group that they belong to, from which the GID is assigned to files they create.

Note Bear in mind that users can be members of more than one group, although all users have a main group that they belong to, from which the GID is assigned to files they create.

As with user accounts, deleting a group is simply a matter of highlighting it in the list and clicking the Delete button. You should ensure that the group no longer has any members before doing this, because Ubuntu won’t prevent you from removing a group that has members (although it will warn you that this is a bad thing to do).

![]() Note Ubuntu appears to offer protection against the havoc caused by deleting a group that is the main group of users on your system. When we deleted an entry that was the main group of a different user and then logged in as that user, the group was automatically re-created! You shouldn’t rely on this kind of protection, however, and should always check before deleting a group.

Note Ubuntu appears to offer protection against the havoc caused by deleting a group that is the main group of users on your system. When we deleted an entry that was the main group of a different user and then logged in as that user, the group was automatically re-created! You shouldn’t rely on this kind of protection, however, and should always check before deleting a group.

As you might have guessed, to manually add a user under Ubuntu, not only must you create a group and then add the user to it, but you must also add that user to the required selection of supplementary groups. Some groups are considered mandatory for effective use of the computer, such as plugdev, while others are optional, depending on how much freedom you want to afford the new user (see Table 21-1).

Adding and Changing Passwords

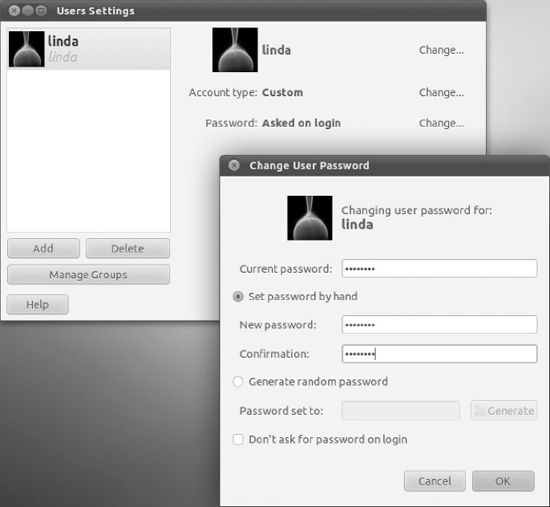

On a default Ubuntu installation, ordinary users are able to change their own passwords by using the Users and Groups tool. Select your user account from the list and click the Change button next to the Password field. You will be prompted with the Change User Password window, shown in Figure 21-3, in which you must enter your current password and select the new one, with the same options as when you originally created the account.

Figure 21-3. The Change User Password window

You need root privileges to change other users’ passwords, but the procedure is the same. For obvious security reasons, Ubuntu won’t allow blank passwords. (It might allow you to set a blank password, but then it won’t let that user log in—this is an interesting way of disabling a user account).

You can enter just about anything as a password, but you should bear in mind some common-sense rules. Ideally, passwords should be at least eight characters long and contain letters, numbers, and even punctuation symbols. You might also want to include both uppercase and lowercase letters, because that makes passwords harder to guess.

![]() Tip You can temporarily switch into any user account by using the Switch From option on the Shutdown menu. In this way your session will be kept open. If you log out, on the other hand, the session will be closed and you’ll need to save your open documents to keep them for future use.

Tip You can temporarily switch into any user account by using the Switch From option on the Shutdown menu. In this way your session will be kept open. If you log out, on the other hand, the session will be closed and you’ll need to save your open documents to keep them for future use.

Understanding File and Folder Permissions

One of the main reasons why users and groups exist is to manage different permissions for different people. Each file and folder on your disk has permissions associated with it, along with a user and group who own it. Without permissions, a user cannot do anything to a file.

Viewing Permissions

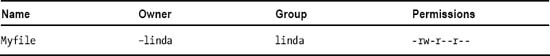

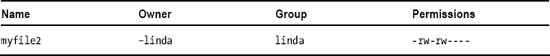

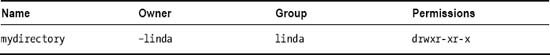

Within Nautilus, is easy to see the users and groups who own a file or folder and the permissions associated with it. Simply select the List view; then select the View Visible Columns option from the menu and check the Owner, Group, and Permissions boxes. Here’s an example of one line of a file listing from our test PC:

In the Permissions column are the permissions for the file or folder. The permission list usually consists of the characters r (for read), w (for write), x (for execute), and/or — (meaning none are applicable).

The Owner column lists the owner of the file (linda in this example) and the group that has permission to access the file (in this case, linda).

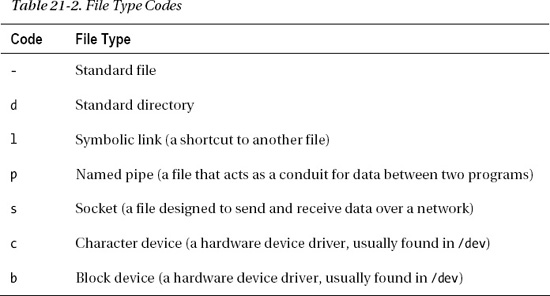

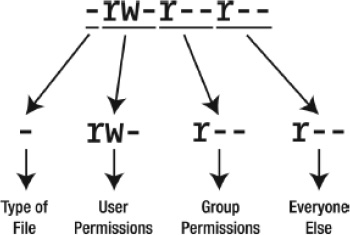

The file permissions part of the listing might look confusing, but it’s actually quite simple. To understand what’s going on, you need to split it into four groups, as illustrated in Figure 21-4.

Figure 21-4. The file permissions part of a file listing can be broken down into four separate parts.

The four groups are as follows:

Type of file: This character represents the file type. A standard data file is indicated with a hyphen (

-). Most files on your system fall into this category. Adshows that the entry is not a file, but a directory. Table 21-2 lists the file type codes.User permissions: Next come the permissions of the person who owns the file. The three characters indicate what the person who owns the file can do with it. The owner of a file is usually the user who created it, although the owner can be changed later on. In this example,

rw-is shown. This means that the owner of the file can read (r) and write (w) to the file. In other words, she can look at it and also save changes to it. However, there’s a hyphen after therw, which indicates that the user cannot execute the file. If this were possible, there would be anxin this spot instead.Group permissions: After the owner’s permissions are the permissions given to the specified group that the file is assigned to. This is indicated by another three characters in the same style as those for user permissions. In the example, the group’s permission is

r--, which means that the members of the specified group can read the file but don’t have permission to write to it, because there’s a hyphen where thewwould normally appear. In other words, as far as they’re concerned, the file is read-only.Everyone else’s permissions: The last set of permissions indicates the permissions of everyone else on the system (other users in other groups). In the example, they can only read the file (

r); the two hyphens that follow indicate that others cannot write to or execute the file.

As with Windows, programs are stored as files on your hard disk, just like standard data files. On Linux, program files need to be explicitly marked as being executable. This is indicated in the permission listing by an x. Therefore, if there’s no x in a file’s permissions, it’s a good bet that the file in question isn’t a program or script (although this isn’t always true for various technical reasons).

To make matters a little more confusing, if the entry in the list of files is a directory (indicated by a d), then the rules are different. In this case, an x indicates that the user can access that directory. If there’s no x, the user’s attempts to browse to that directory will be met with an “access denied” message.

File permissions can be difficult to understand, so let’s look at a few real-world examples. These examples assume that you’re logged into Linux as the user ubuntu.

Typical Data File Permissions

Here’s the first example:

You know that this file is owned by user linda because that username appears in the Owner column. Also notice that the group linda has access to the file, although precisely how much depends on the permissions.

From left to right, the initial file permission character is a hyphen, which indicates that this is an ordinary file and has no special characteristics. It’s also not a directory.

After that is the first part of the permissions, rw-. These are the permissions for the owner of the file, linda. You’re logged in as that user, so this file belongs to you, and these permissions apply to you. You can read and write to the file but not execute it. Because you cannot execute the file, you can infer that this is a data file, not a program (there are certain exceptions to this rule, but we’ll ignore them for the sake of simplicity).

Following this is the next part of the file permissions, rw-. This tells you what members of the group linda can do with the file. It’s fairly useless information if you’re the only user of your PC, but for the record, it tells you that anyone else belonging to the group Ubuntu can also read and write the file but not execute it. If you’re not the only user of a computer, group permissions can be important. The “Altering Permissions” section, coming up shortly, describes how to change file permissions to control who can access files.

Finally, the last three characters tell you the permissions of everyone else on the system. The three hyphens (---) mean that they have no permissions at all regarding the file. There’s a hyphen where the r normally appears, so they cannot even read it. The hyphens afterward tell you they cannot write to the file or execute it. If they try to do anything with the file, they’ll get a “permission denied” error.

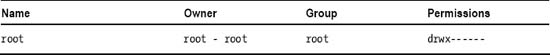

Permissions on a User’s Directory

Here’s another example:

The list of permissions starts with d, which tells you that this isn’t a file but a directory. After this is the list of permissions for the owner of the directory (linda), who can read files in the directory and also create new ones there. The x indicates that you can access this directory, as opposed to being turned away with an “access denied” message. You might think being able to access the directory is taken for granted if the user can read and write to it, but that’s not the case.

Next are the permissions for the group members. They can read files in the directory but not write any new ones there (although they can modify files already there, provided the permissions of the individual files allow this). Once again, there’s an x at the end of their particular permission listing, which indicates that the group members can access the directory.

Following the group’s permissions are those of everyone else. They can read the directory and browse it, but not write new files to it, as with the group users’ permissions.

Permissions on a Directory Owned by Root

Here’s the last example:

You can see that the file is owned by root. Remember that in this example, you’re logged in as linda and your group is linda.

The list of permissions starts with a d, so you can tell that this is actually a directory. After this, you see that the owner of the directory, root, has permission to read, write, and access the directory.

Next are the permissions for the group: three hyphens. In other words, members of the group called root have no permission to access this directory in any way. They cannot browse it, create new files in it, or even access it.

Following this are the permissions for the rest of the users. This includes you, because you’re not the user root and don’t belong to its group. The three hyphens mean you don’t have permission to read, write, or access this directory. In other words, it’s out of bounds to you, probably because it contains files that only the root user should access!

Altering Permissions

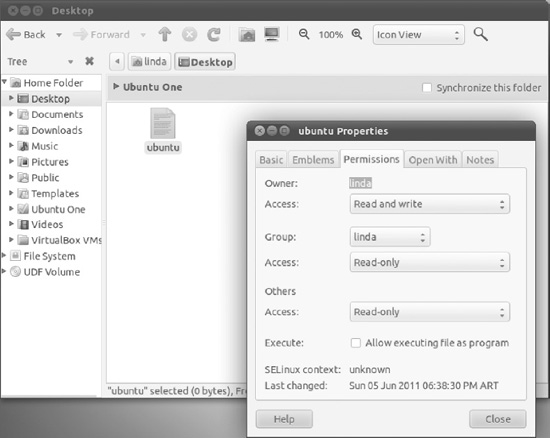

You can easily change permissions of files and directories within Nautilus. You must be the owner of a file to change its permissions (or you can be root, of course; remember to use Gksudo in the Run Applications dialog box to open Nautilus with root privileges). Just right-click a file and select Properties.

Figure 21-5 shows the Permissions tab of a file. You can set permissions for the owner, group, or everybody else. The available permissions are None (no access), Read-Only, and Read and Write. The permissions are applied automatically when you select them; if you keep your Nautilus windows open and visible behind the file properties window, you will see this, as the permissions get updated almost instantly.

Figure 21-5. The file Permissions tab

You can enable the Execute permission by checking the “Allow executing file as program” check box. It applies for the owner, group, and other users alike.

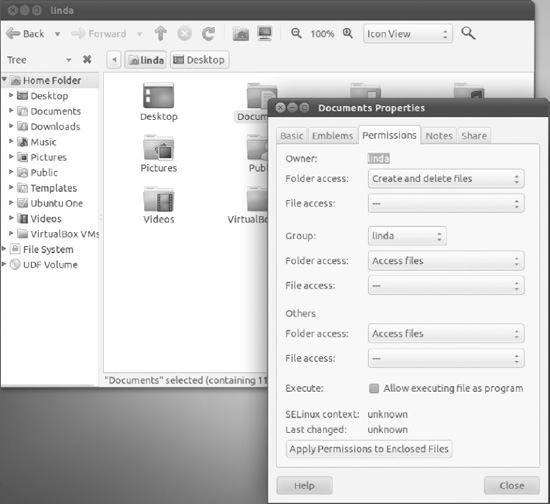

The permissions on a folder are somewhat more complicated, as shown in Figure 21-6.

Figure 21-6. The folder Permissions tab allows you to change its files’ permissions as well.

You can change the group of the folder by selecting the one you want in the Group drop-down list.

There are three levels of folder access that you can set at any particular folder for the owner, the group, and everybody else: List Files Only (which really allows read access to the folder), Access Files (which allows read and execute access), and Create and Delete Files (which allows read, write, and execute access). You can also change the permissions applied to the files contained in the folder by selecting the appropriate level in each of the “File access” dialog boxes: Read-Only or Read and Write. Check the “Allow executing file as program” box to set the Execute permission on contained files. Click the Apply Permissions to Enclosed Files button to propagate the changes down into the hierarchy.

To change the ownership of a file or folder, you need to have root privileges, so make sure you open Nautilus with Gksudo. In the Owner field, select the user.

![]() Tip Directory permissions are rather strange in that it’s easy to set confusing and even illogical permissions. Generally speaking, the day-to-day rules you should follow are simple. If you wish to stop a particular user from accessing a directory, remove all permissions—Read, Write, and Execute (

Tip Directory permissions are rather strange in that it’s easy to set confusing and even illogical permissions. Generally speaking, the day-to-day rules you should follow are simple. If you wish to stop a particular user from accessing a directory, remove all permissions—Read, Write, and Execute (rwx). If you wish to make a directory read-only, leave the Read and Execute permissions in place, but remove the Write permission (r-x). It’s even possible to make a directory write-only, by leaving the Write and Execute permissions in place and removing the Read permission (-wx). However, it’s rare that you would want to do this.

NUMERIC FILE PERMISSIONS

![]() Tip You can view the octal notation by adding the column in Nautilus. Select View Visible Columns, and check the box next to Octal Permissions.

Tip You can view the octal notation by adding the column in Nautilus. Select View Visible Columns, and check the box next to Octal Permissions.

Summary

In this chapter you got to know two important elements of the Ubuntu experience, largely derived from its UNIX and Linux predecessors: users and permissions. These are important concepts that lay the foundation of the security implemented in Ubuntu. Through users, people can have their own experiences, configurations, data, and permissions. An important characteristic is that every user account can have its own files and set permissions on them. What files a user can change determines in brief what that user can do with the system.

We discussed the differences between root and standard users, and how to allow temporary access to root’s privileges. We showed you the steps to create users and group accounts, and investigated the sometimes puzzling notation for file and folder permissions. Once you’ve mastered the basics, you should be ready to set permissions on your own.