There’s no disputing the fact that there is a key reason why many digital SLR buyers choose Nikon cameras: Nikon lenses. Some favor Nikon cameras because of the broad selection of quality lenses. Others already possess a large collection of Nikon optics (perhaps dating from the owner’s photography during the film era), and the ability to use those lenses on the latest digital cameras is a big plus. Many choose Nikon because of the overall image and build quality of the Nikon lineup.

It’s true that there is a mind-bending assortment of high-quality lenses available to enhance the capabilities of Nikon cameras. In mid-2016, Nikon announced the production of its 100 millionth Nikkor lens. You can use thousands of current and older lenses introduced by Nikon and third-party vendors since 1959, although lenses made before 1977 may need an inexpensive modification (roughly $35 per lens) for use with your D500 (more on this later). These lenses can give you a wider view, bring distant subjects closer, let you focus closer, shoot under lower light conditions, or provide a more detailed, sharper image for critical work. Other than the sensor itself, the lens you choose for your dSLR is the most important component in determining image quality and perspective of your images.

This chapter explains how to select the best lenses for the kinds of photography you want to do.

Sensor Sensibilities

From time to time, you’ve heard the term crop factor, and you’ve probably also heard the term lens multiplier factor. Both are misleading and inaccurate terms used to describe the same phenomenon: the fact that cameras like the D500 (and most other affordable digital SLRs) provide a field of view that’s smaller and narrower than that produced by certain other (usually much more expensive) cameras, when fitted with exactly the same lens.

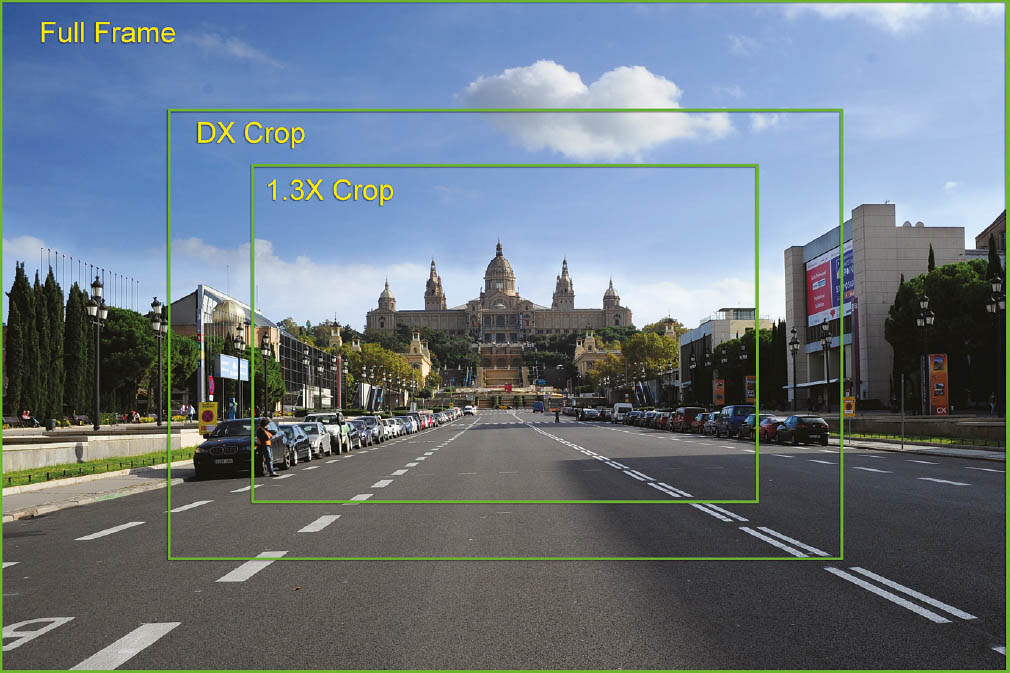

Figure 7.1 quite clearly shows the phenomenon at work. The outer rectangle, marked Full Frame, shows the field of view you might expect with a 35mm wide-angle lens mounted on one of Nikon’s “full-frame” (non-cropped) cameras, like the Nikon D810, D750, D610, or D5. The area marked DX Crop shows the field of view you’d get with that 35mm lens installed on a D500, in DX mode. Inside, marked 1.3X Crop, is the field of view when using the D500 in 1.3X crop mode. It’s easy to see from the illustration that the full-frame rendition provides a wider, more expansive view, while the two inner fields of view are, in comparison, cropped.

The cropping effect is produced because the sensors of DX cameras like the Nikon D500 are smaller than the sensors of the Nikon D5, D810, D750, D610, and earlier full-frame cameras. The “full-frame” camera has a sensor that’s the size of the standard 35mm film frame, 24mm × 36mm. Your D500’s sensor does not measure 24mm × 36mm; instead, it specs out at approximately 24mm × 16mm. In 1.3X crop mode, the effective frame size is 18mm × 12mm.

The cropped sensor effect is most useful when using longer lenses, where extra “reach” is considered a benefit. So, using a 100mm lens instead as an example, when that optic is mounted on a D500 it has the same field of view as a 150mm lens on the Nikon D810. In DX 1.3X crop mode (which actually produces an effective 2X crop compared to a full-frame image), the field of view is equivalent to a 200mm lens. The optional DX 1.3X crop is a boon to sports and wildlife photographers who want to “extend” the reach of their lens without the need to manually crop each shot in an image editor. You can enable the DX 1.3X crop using the Choose Image Area entry in the Photo Shooting menu, as described in Chapter 11.

Figure 7.1 The relative fields of view of full-frame (1X), DX (1.5X), and DX 1.3 (2X) crops.

This translation is generally useful only if you’re accustomed to using full-frame cameras (usually of the film variety) and want to know how a familiar lens will perform on a digital camera. I strongly prefer crop factor over lens multiplier, because nothing is being multiplied; a 100mm lens doesn’t “become” a 150mm lens—the depth-of-field and lens aperture remain the same. (I’ll explain more about these later in this chapter.) Only the field of view is cropped. But crop factor isn’t much better, as it implies that the 24 mm × 36mm frame is “full” and anything else is “less.” I get e-mails all the time from photographers who point out that they own full-frame cameras with 36mm × 48mm sensors (such as the Mamiya or Hasselblad medium-format digitals). By their reckoning, the “half-size” sensors found in cameras like the Nikon D810 and D5 are “cropped.”

If you’re accustomed to using full-frame film cameras, you might find it helpful to use the crop factor “multiplier” to translate a lens’s real focal length into the full-frame equivalent, even though, as I said, nothing is actually being multiplied. Throughout most of this book, I’ve been using actual focal lengths and not equivalents, except when referring to specific wide-angle or telephoto focal length ranges and their fields of view.

Crop or Not?

There’s a lot of debate over the “advantages” and “disadvantages” of using a camera with a “cropped” sensor, versus one with a “full-frame” sensor. The arguments go like this:

- “Free” 1.5X/2X teleconverter. The Nikon D500 (and other cameras with the 1.5X crop factor), magically transforms any telephoto lens you have into a longer lens, which can be useful for sports, wildlife photography, and other endeavors that benefit from more reach. Yet, your f/stop remains the same (that is, a 300mm f/4 becomes a very fast 450mm f/4 lens, or super-fast 600mm f/4 optic with the 1.3X crop). Some discount this advantage, pointing out that the exact same field of view can be had by taking a full-frame image, and trimming it to the cropped equivalent. While that is strictly true, it doesn’t take into account a factor called pixel density.

- Dense pixels = more noise. The other side of the pixel density coin is that the denser packing of pixels to achieve 20.7 megapixels in the D500 sensor means that each pixel must be smaller, and will have less light-gathering capabilities. Larger pixels capture light more efficiently, reducing the need to amplify the signal when boosting ISO sensitivity, and, therefore, producing less noise. In an absolute sense, this is true, and cameras like the D5 do have sensational high ISO performance. However, the D500’s sensor is improved over earlier cameras, so you’ll find it performs very well at higher ISOs—considerably better than its predecessor, the D300s, which had larger pixels and “only” 12 megapixels of resolution.

- Lack of wide-angle perspective. Of course, the 1.5X default “crop” factor applies to wide-angle lenses, too, so your 20mm ultra-wide lens becomes a hum-drum 30mm near-wide-angle, and a 35mm focal length is transformed into what photographers call a “normal” lens. Zoom lenses, like the 16-80mm f/2.8-4 lens that is often purchased with the D500 in a kit, have less wide-angle perspective at their minimum focal length. The 16-80mm optic, for example, is the equivalent of a 24mm moderate wide angle when zoomed to its widest setting. Nikon has “fixed” this problem by providing several different extra-wide zooms specifically for the DX format, including the (relatively) affordable 12-24mm and 10-24mm DX Nikkors. You’ll never really lack for wide-angle lenses, but some of us will need to buy wider optics to regain the expansive view we’re looking for.

- Mixed body mix-up. The relatively small number of Nikon D500 owners who also have an affordable Nikon full-frame camera like the D610 or D750 can’t ignore the focal-length mixup factor. If you own both FX- and DX-format cameras (some D500 owners use them as a backup to a D750, for example), it’s vexing to have to adjust to the different fields of view that the cameras provide. If you remove a given lens from one camera and put it on the other, the effective focal length/field of view changes. That 16-35mm zoom works as an ultra-wide to wide angle on a D750, but functions more as a moderate wide-angle to normal lens on a D500. To get a somewhat similar “look” on both cameras, you’d need to use a 12-24mm zoom on the D500, and the 16-35mm zoom on the D750. It’s possible to become accustomed to this field of view shake-up and, indeed, some photographers put it to work by mounting their longest telephoto lens on the D500 and their wide-angle lenses on their full-frame camera. Even if you’ve never owned both an FX and DX camera, you should be aware of the possible confusion.

Your First Lens

Some Nikon dSLRs are almost always purchased with a lens. The Nikon D500 is sometimes bought by those new to digital SLR photography who find the AF-S DX Nikkor 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR or even the more costly AF-S DX Nikkor 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR (both shown in Figure 7.2) irresistible bargains. Both have shake-canceling vibration reduction built in. Other Nikon models, including the Nikon D5, Df, and D810, are often purchased without a lens by veteran Nikon photographers who already have a complement of optics to use with their cameras.

I bought my D500 as a body only, an option that was available immediately at camera introduction. Depending on which category of photographer you fall into, you’ll need to make a decision about what kit lens to buy, or decide what other kind of lenses you need to fill out your complement of Nikon optics. This section will cover “first lens” concerns, while later in the chapter we’ll look at “add-on lens” considerations.

When deciding on a first lens, there are several factors you’ll want to consider:

- Cost. You might have stretched your budget a bit to purchase your Nikon D500, so the 18-140mm VR kit lens helps you keep the cost of your first lens fairly low. In a kit, this lens may tack on just $300 to the price of the body alone. In addition, there are other excellent moderately priced lenses available that will add from $100 to $500 to the price of your camera if purchased at the same time.

Figure 7.2 The AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR (left), and AF-S DX Nikkor 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR (right) can be purchased as the basic kit lens for the D500.

- Zoom range. If you have only one lens, you’ll want a fairly long zoom range to provide as much flexibility as possible. Fortunately, several popular basic lenses for the D500 have 3X to 7.8X zoom ranges (I’ll list some of them next), extending from moderate wide-angle/normal out to medium telephoto. These are all fine for everyday shooting, portraits, and some types of sports.

- Adequate maximum aperture. You’ll want an f/stop of at least f/3.5 to f/4 for shooting under fairly low light conditions. The thing to watch for is the maximum aperture when the lens is zoomed to its telephoto end. You may end up with no better than an f/5.6 maximum aperture. That’s not great, but you can often live with it, particularly with a lens having vibration reduction (VR) capabilities, because you can often shoot at lower shutter speeds to compensate for the limited maximum aperture.

- Image quality. Your starter lens should have good image quality, because that’s one of the primary factors that will be used to judge your photos. Even at a low price, several of the different lenses that can be used with the D500 kit (such as the 18-140mm zoom) include extra-low dispersion glass and aspherical elements that minimize distortion and chromatic aberration; they are sharp enough for most applications. If you read the user evaluations in the online photography forums, you know that owners of the kit lenses have been very pleased with their image quality.

- Size matters. A good walking-around lens is compact in size and light in weight.

- Fast autofocusing. Your first lens should have a speedy autofocus system (which is where the Silent Wave motor found in all but the bargain basement lenses [older, non-AF-S models] is an advantage). (Many—but not all—third-party lenses also have fast internal focus motors.)

- Close focusing. The ability to focus down to 12 inches or closer will let you use your basic lens for some types of macro photography.

You can find comparisons of the lenses discussed in the next section, as well as evaluations of lenses I don’t describe, third-party optics from Sigma, Tokina, Tamron, and other vendors, in online groups and websites.

Buy Now, Expand Later

A pro camera like the D500 deserves the best lenses you can afford. Unfortunately, the price tag for upgrading to Nikon’s flagship DX model can be steep enough to limit your initial choices. As I noted earlier, when the Nikon D500 was introduced, it was available both in kit form with the 16-80mm VR lens and in body-only packaging. However, there are other options. The following optics are all good, basic lenses; each can serve you well as a “walk-around” lens (one you keep on the camera most of the time, especially when you’re out and about without your camera bag). The number of choices is actually quite amazing, even if your budget is limited to less than $350 for your first lens. Here’s a list of Nikon’s best-bet “first” lenses. Don’t worry about sorting out the alphabet soup right now; I provide a complete list of Nikon lens “codes” later in the chapter.

- AF-S DX Nikkor AF-S DX 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR. Introduced in 2015, this lens, at roughly $1,100, is a significant upgrade from the 16-85mm lens it replaced and is the standard D500 kit lens at most retailers. It adds around $570 to the price of the body alone, giving you, in effect, a $500-plus discount from the full list price for this lens. (See Figure 7.2, right.)

- AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-120mm f/4G ED VR. If you can live without the focal lengths from 16-23mm (or plan to add a wide-angle zoom that covers that range, such as the Nikon DX 12-24mm or 10-20mm optics), I actually recommend this one over the kit lens. Priced at around $1,100, it has a constant f/4 maximum aperture that doesn’t change as you zoom, and has a very useful zoom range. As a bonus, it is a full-frame lens, so if you ever decide to upgrade to a full-frame camera, you can take this lens along with you. There are two older versions with f/3.5-f/5.6 variable maximum apertures that you might see available on the used market; they’re not as sharp or built as well and should be avoided.

- AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. This is the Nikon DX kit lens offered as an upgrade for the D7200 and other non-pro DX bodies. It has an extended 7.8X zoom range, a minimum focus distance of roughly 18 inches, and manual focus override that allows you to fine-tune focus after the D500 has set basic focus automatically. (That feature is especially useful when shooting macro images or working with selective focus techniques when you might want to select a focus point that’s slightly different from what the camera selects.) Its $500 list price makes this lens a better buy in a kit (which lowers the effective tariff to around $300). (See Figure 7.2, left.)

- AF-S DX Nikkor 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR II. This older lens is one of my economical choices as a “walking-around” lens for this camera. I much prefer it over the 18-200mm VR (described later), even though it has a more limited zoom range. Its focal length range is quite sufficient for most general photography. You might want this as an everyday lens to use in conjunction with some premium non-zoom primes, like the 85mm f/1.4 or 58mm f/1.4 lenses.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G VR II. If you already own this $250 lens, you can continue to use it with your D500, mostly likely supplemented by other optics. This new collapsible VR version of the 18-55mm should not be your first choice, even when costs must be kept low. Fortunately, the vibration reduction (“anti-shake”) feature of this lens partially offsets the relatively slow maximum aperture at the telephoto position. Cash-strapped D500 owners can mate this lens with Nikon’s AF-S DX VR Zoom-Nikkor 55-200mm f/4-5.6G IF-ED to obtain a two-lens VR pair that will handle everything from 18mm to 200mm, at a relatively low price.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. The 16-85mm VR lens is the zoom that would make a lot of sense as a kit lens for the D500 if there weren’t better choices available. It’s still available new for about $700, but I expect it will probably be discontinued soon, as the 16-80mm lens described above effectively provides a (more expensive) replacement. If you really want to use just a single lens with your camera, this one provides an excellent combination of focal lengths, image quality, and features. Its zoom range extends from a true wide angle (equivalent to a 24mm lens on a full-frame camera) to useful medium telephoto (about 128mm equivalent), and so can be used for everything from architecture to portraiture to sports. If you think vibration reduction is useful only with longer telephoto lenses, you may be surprised at how much it helps you hand-hold your D500 even at the widest focal lengths. The only disadvantage to this lens is its relatively slow speed (f/5.6) when you crank it out to the telephoto end.

- AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 18-70mm f/3.5-4.5G IF-ED. If you don’t plan on getting a longer zoom-range basic lens and can’t afford the 16-80 zoom, I highly recommend this aging, but impressive lens, if you can find one in stock as a used item, as it is long-since discontinued. Originally introduced as the kit lens for the venerable Nikon D70, the 18-70mm zoom quickly gained a reputation as a very sharp lens at a bargain price. It doesn’t provide a view that’s as long or as wide as the 16-80mm, but it’s a half-stop faster at its maximum zoom position. You may have to hunt around to find one of these, but they are available for $200 or even less and well worth it. I own one to this day, and use it regularly, although it spends most of its time installed on my D3200, which has been converted to infrared-only photography.

- AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 18-135mm f/3.5-5.6G IF-ED. This lens has been sold as a kit lens for cameras aimed at intermediate amateur-level shooters, and some retailers with stock on hand are packaging it with the D500 body as well. While decent, this predecessor of the current 18-140mm VR model is really best suited for the crowd who buy one do-everything lens and then never purchase another. Available for less than $300, you won’t tie up a lot of money in this lens. There’s no VR, so, for most, the 18-105mm VR or 18-140mm VR lens is a better choice.

- AF-S DX VR II Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6G IF-ED. I owned this $600 lens for about three months, and decided it really didn’t meet my needs. It was introduced as an ideal “kit” lens for the Nikon D200 many years ago, and, at the time had almost everything you might want. It’s a holdover, more upscale kit lens for the D500. Its stunning 11X zoom range covers everything from the equivalent of 27mm to 300mm when the 1.5X crop factor is figured in, and its VR capabilities plus light weight let you use it without a tripod most of the time. However, I found the image quality to be good, but not outstanding, and the slow maximum aperture at 200mm to be limiting when a fast shutter speed is required to stop action. The “zoom creep” (a tendency for the lens to zoom when the camera is tilted up or down) found in many examples will drive you nuts after a while. Fortunately, the newer version with improved VR and with the creep fixed has been available for some time.

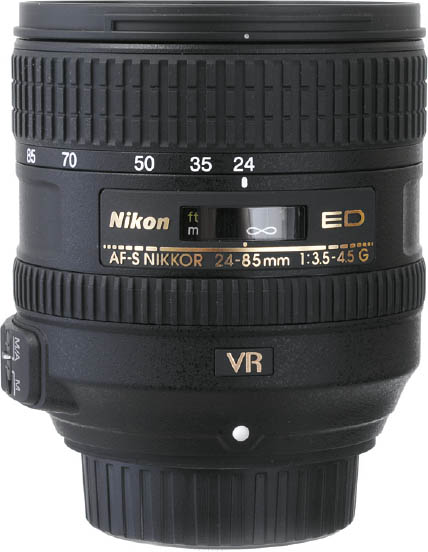

- AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G. Priced at about $500, this lens is reasonably priced, and has the advantage (like the 24-120mm lens) of being a full-frame optic, so if you upgrade in the future to a Nikon FX camera, you can take this one along with you. I happen to own both this lens and Nikon’s much more expensive 24-70mm f/2.8 optic (the non-VR version, priced at about $1,800), and tend to use this one (which costs less than one-third as much) much more often. It’s not as fast at its maximum zoom setting, but offers a bit more reach, vibration reduction, and is much more compact. This is an excellent walk-around lens for the D500 if you don’t need the extra-wide 18-23mm focal lengths. (See Figure 7.4.)

Figure 7.3 The AF-S DX VR II Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6G IF-ED is a lightweight “walking-around” lens.

Figure 7.4 This AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G lens is affordable, and is compatible with full-frame cameras, too.

When you’re ready to expand your DX lens collection, the following lenses are some of your best-bet options. If an FX camera is in your future, I’ll describe some full-frame lenses at the end of this chapter.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 12-24 f/4G IF-ED. This $1,150 lens was the original wide zoom for DX cameras, and is great for those who want a fast, constant f/4 maximum aperture and don’t need an ultra-wide view. It’s still available new, as an extra-cost option with a more rugged build, and a front thread that accepts “professional” 77mm filters.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5G ED. If you need a wider view and lower price, this newer lens, at $900, is the most popular Nikon ultra-wide lens for the D500. It focuses nearly three inches closer than its older sibling.

- AF Fisheye-Nikkor 10.5mm f/2.8G ED. The only “drawbacks” to this superb fisheye are its inability to use external filters and its non-removable lens hood. Fortunately, the $775 lens can use rear-mounted gelatin filters (front filters would vignette significantly, anyway), and many enterprising souls have managed to file off the hood to capture an even wider non-circular view.

Warning: This is not an AF-S lens, and relies on the focusing motor built into your D500 and many other upscale Nikon cameras. It will not autofocus on any D5xxx or D3xxx series camera, if you happen to own one. That’s virtually a moot point, anyway, given that the depth-of-field of this optic encompasses typical subjects from a few feet away to infinity.

- AF-S 35mm f/1.8G DX. If you want a fast, inexpensive “normal” lens for your D500 for street photography, interiors, photojournalism, or indoor sports, this $200 lens fills the bill.

- AF-S 40mm f/2.8G DX Micro-Nikkor. This lens and the 85mm optic described next make up Nikon’s reasonably priced macro lens lineup. This one is just $280 and does an excellent job. I describe Nikon’s broader range of full-frame macro lenses at the end of this chapter.

- AF-S 85mm f/3.5G ED DX Micro-Nikkor VR. A bit more expensive at about $530, this longer Micro-Nikkor gives you a bit more distance from skittish subjects (like insects) and has vibration reduction so you can often shoot nature close-ups hand-held. Keep in mind that VR won’t freeze fronds swaying in the breeze; you’ll still need to use higher shutter speeds on windy days.

- AF-S 17-55 f/2.8G DX IF-ED. This was the first “pro” lens for the DX format and remains a popular, if expensive (at around $1,500) option. Personally, if I didn’t need a fast f/2.8 constant maximum aperture, I’d prefer to spend those bucks on a similar full-frame lens, like the 24-120mm f/4, which has VR to boot.

- AF-S 55-300mm f/4.5-5.6G DX VR. For the price, this lens is an excellent lens in the short telephoto to supertelephoto range. Its $400 price tag won’t deplete your pocketbook as much as Nikon’s 18-300mm lens if you don’t need the wide-angle focal lengths. It’s a better performer at the telephoto lens, as well.

- AF-S 55-200mm f/4-5.6G DX ED VRII / AF-S 55-200mm f4.5-5.6 DX IF-ED VR. Nikon offers two lenses in the 55-200mm focal length range; a newer version with upgraded VR at $350, and an older model with similar specs, but less advanced vibration reduction. If you can locate one, the latter lens can often be purchased new for around $200. It’s not as sharp as its upgraded sibling, but it can make a good addition to your camera bag until you can afford a deluxe version.

Your Best Do-Everything Option?

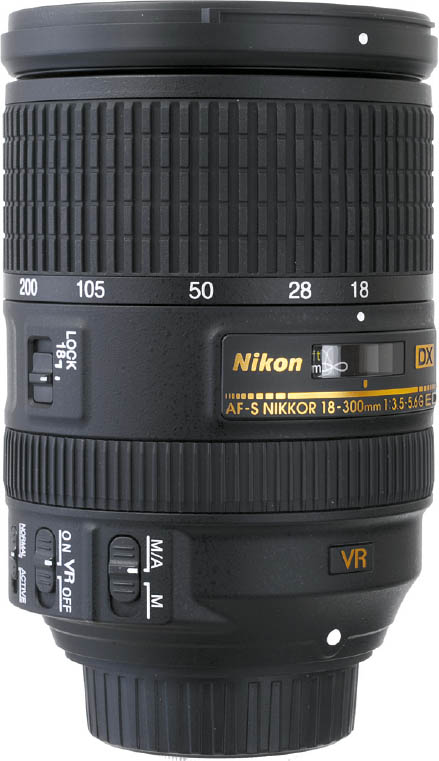

Nikon has introduced an updated version of a DX lens originally unveiled in 2012. It might actually be the best do-everything option for some D500 shooters, if top-notch image quality at every focal length is not a priority. The $1,000 AF-S DX Nikkor 18-300mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR zoom has an incredible 16.7X zoom range, yet is relatively light and compact, focuses close, and has image stabilization built in. (See Figure 7.5.) It’s become a standard walk-around lens for many DX format users, because its 27-450mm equivalent focal length range is spectacular for sports and wildlife. It’s not the sharpest lens at its maximum focal length, but it more than makes up for a little softness at the far end with versatility.

Figure 7.5 Nikon’s versatile 18-300mm f/3.5-5.6 G ED VR zoom lens.

- Ultra-long zoom range. Used on your D500, this lens provides the equivalent field of view as a full-frame 27-400mm lens. That’s sort of wide to supertelephoto, without the need to swap lenses. That versatility is important when shooting stills, of course, especially with sports and other rapidly changing scenes. But if you’re shooting movies, the 18-300mm focal lengths come in especially handy. You can capture a wide establishing shot to set the scene, switch to a medium shot to draw viewer attention to your main subjects, then capture an extreme close-up. Even if you’re collecting short clips, the action may be continuing between “takes,” so if you had to switch lenses you might miss something. Not so with this lens. You can change field of view between each shot as quickly as you can rotate the zoom ring. The lens’s long range has some possibilities for those mind-boggling quick zooms in or out during video capture, too. (Use with restraint!) The only drawback this lens has is that it is not especially sharp as a telephoto from 200-300mm, nor at the widest angle settings. If most of your work requires 18-200mm focal lengths and you have an occasional need for the 200-300mm range (and don’t want to shoot wide open), this lens can be very useful. However, sports and wildlife photographers who would use the longest focal lengths of this lens extensively would probably be better served by the AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6G IF-ED, which is about 1/3 less expensive, sharper at 300mm, and will work on full-frame cameras should you upgrade later on.

- Vibration reduction. It’s so common to have VR in telephoto lenses these days, especially those with equivalent or actual focal lengths of 400mm or more, that you might not stop to think how rare image stabilization is at the other end. While it’s arguable that VR is less essential in a wide-angle lens because camera shake blur is less of a problem, having a lens that starts wide and goes all the way to supertelephoto with optical image stabilization built in is a definite plus.

- Compact size. Although it replaces a half-dozen or more lenses, the 18-300mm zoom measures just 3.3 × 4.7 inches and weighs 1 pound, 13 ounces, which is svelte for a 300mm lens (even if a bit large for an 18mm wide angle). However, it almost doubles in length when cranked out to its full 300mm setting, becoming lanky instead of svelte. Even so, in weight and size, your do-everything walk-around lens compares favorably to its 18-200mm predecessor (3 × 3.8 inches, 1 pound, 4 ounces), takes pro-standard 77mm filters (vs. 72mm for the older model), and has a lock to totally prevent dreaded zoom creep, to boot. Mine doesn’t exhibit creep even with the lock off, however.

- Close focusing. The 18-300mm has the ability to focus down to 1.48 feet at 300mm, giving you a 1:3.2X maximum reproduction ratio (about one-third life-size in DX format). The 18-300mm is not a true macro lens, but when you’re venturing out with a single lens on your D500, the ability to focus that closely at 300mm is the next best thing.

- Good (not great) image quality. Nikon says that three extra-low dispersion (ED) elements and three aspheric elements deliver the promised minimized chromatic aberration (which can be especially troublesome at wide-angle focal lengths), and the typical aberrations that appear when a lens is used at larger apertures (that’s something that will probably happen given the relatively slow f/5.6 maximum aperture at 300mm). Nikon touts this lens’s 9-bladed aperture for its pleasing bokeh, too. (I’ll show you the effects of bokeh later in this chapter.) As I said earlier, this lens delivers useful image quality even if it’s not the sharpest 300mm lens you can own.

What Lenses Can You Use?

The previous section helped you sort out what basic lens you need to buy with your Nikon D500. Now, you’re probably wondering what lenses can be added to your growing collection (trust me, it will grow). You need to know which lenses are suitable and, most importantly, which lenses are fully compatible with your Nikon D500.

With the Nikon D500, the compatibility issue is a simple one: It can use any modern-era Nikon lens with the AF-S designation, with full availability of all autofocus, auto aperture, autoexposure, and image stabilization features (if present). You can also use any Nikon AI, AI-S, or AI-P lens, which are manual focus lenses that were produced starting in 1977 and continue in production effectively through the present day, because Nikon continues to offer a limited number of manual focus lenses for those who need them.

Today, in addition to its traditional full-frame lenses, Nikon offers lenses with the DX designation, which is intended for use only on DX-format cameras, like your D500. While the lens mounting system is the same, DX lenses have a coverage area that fills only the smaller frame, allowing the design of more compact, less-expensive lenses especially for non-full-frame cameras. The AF-S DX Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G, a fixed focal length (non-zoom) lens with a fast f/1.8 maximum aperture, is an example of such a lens.

Ingredients of Nikon’s Alphanumeric Soup

Nikon has always been fond of appending cryptic letters and descriptors onto the names of its lenses. Here’s an alphabetical list of lens terms you’re likely to encounter, either as part of the lens name or in reference to the lens’s capabilities. Not all of these are used as parts of a lens’s name, but you may come across some of these terms in discussions of particular Nikon optics:

- AF, AF-D, AF-I, AF-S, AF-P. In all cases, AF stands for autofocus when appended to the name of a Nikon lens. An extra letter is added to provide additional information. A plain old AF lens is an autofocus lens that uses a slot-drive motor in the camera body to provide autofocus functions (and so cannot be used in AF mode on the entry-level models noted earlier). The D means that it’s a D-type lens (described later in this listing); the I indicates that focus is through a motor inside the lens; and the S means that a super-special (Silent Wave) motor in the lens provides focusing. (Don’t confuse a Nikon AF-S lens with the AF-S [Single-Servo Autofocus mode].) Nikon is currently upgrading its older AF lenses with AF-S versions, but it’s not safe to assume that all newer Nikkors are AF-S, or even offer autofocus. For example, the PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED perspective control lens must be focused manually, and Nikon offers a surprising collection of other manual focus lenses to meet specialized needs. Nikon has recently started introducing lenses marked “AF-P” with faster, quieter stepper motors that make them especially suitable for video

- AI, AI-S. All Nikkor lenses produced after 1977 have either automatic aperture indexing (AI) or automatic indexing-shutter (AI-S) features that eliminate the previous requirement to manually align the aperture ring on the camera when mounting a lens. Within a few years, all Nikkors had this automatic aperture indexing feature (except for G-type lenses, which have no aperture ring at all), including Nikon’s budget-priced Series E lenses, so the designation was dropped at the time the first autofocus (AF) lenses were introduced.

- D. Appended to the maximum f/stop of the lens (as in f/2.8D), a D-Series lens is able to send focus distance data to the camera, which uses the information for flash exposure calculation and 3D Color Matrix II metering.

- DC. The DC stands for defocus control, which allows managing the out-of-focus parts of an image to produce better-looking portraits and close-ups.

- DX. The DX lenses are designed for use with digital cameras using the APS-C–sized sensor having the 1.5X crop factor. The image circle they produce isn’t large enough to fill up a full 35mm frame at all focal lengths, but they can be used on Nikon’s full-frame models using the automatic/manual DX crop mode.

- E. The E designation was used for Nikon’s budget-priced E-Series optics, five prime and three zoom manual focus lenses built using aluminum or plastic parts rather than the preferred brass parts of that era, so they were considered less rugged. All are effectively AI-S lenses. They do have good image quality, which makes them a bargain for those who treat their lenses gently and don’t need the latest autofocus features. They were available in 28mm f/2.8, 35mm f/2.5, 50mm f/1.8, 100mm f/2.8, and 135mm f/2.8 focal lengths, plus 36-72mm f/3.5, 75-150mm f/3.5, and 70-210mm f/4 zooms. (All these would be considered fairly “fast” today.)

However, today the E designation is applied to lenses to represent those that stop down the lens to the “taking” aperture electronically. (During framing, focusing, exposure metering, and other pre-photo steps, the lens always remains at its maximum aperture unless you stop it down using a Preview—depth-of-field preview—button.) Non-E lenses use a lever in the camera body that mates with a lever in the lens mount. Lenses with an E in their names, such as the 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR optic, use an electronic mechanism instead. You should be aware that many older film and digital camera bodies (those produced prior to the D3 and D3000, introduced in 2007, plus the Nikon D90 and D3000) are unable to adjust the aperture of this type of E lens, and must be used wide open.

- ED (or LD/UD). The ED (extra-low dispersion) designation indicates that some lens elements are made of a special hard and scratch-resistant glass that minimizes the divergence of the different colors of light as they pass through, thus reducing chromatic aberration (color “fringing”) and other image defects. A gold band around the front of the lens indicates an optic with ED elements. You sometimes find LD (low dispersion) or UD (ultra-low dispersion) designations.

- FX. When Nikon introduced the Nikon D3 as its first full-frame camera, it coined the term “FX,” representing the nominal 24mm × 36mm sensor format as a counterpart to “DX,” which was used for its 16mm × 24mm APS-C–sized sensors. Although FX hasn’t been officially applied to any Nikon lenses so far, expect to see the designation used more often to differentiate between lenses that are compatible with any Nikon digital SLR (FX) and those that operate only on DX-format cameras, or in DX mode when used on an FX camera like the D700, D800, D3, D3s, D3x, and D4.

- G. G-type lenses have no aperture ring, and you can use them at other than the maximum aperture only with electronic cameras like the D500 that set the aperture automatically. Fortunately, this includes all Nikon digital dSLRs.

- IF. Nikon’s internal focusing lenses change focus by shifting only small internal lens groups with no change required in the lens’s physical length, unlike conventional double helicoid focusing systems that move all lens groups toward the front or rear during focusing. IF lenses are more compact and lighter in weight, provide better balance, focus more closely, and can be focused more quickly.

- IX. These lenses were produced for Nikon’s long-discontinued Pronea 6i and S APS film cameras. While the Pronea could use many standard Nikon lenses, IX lenses cannot be mounted on any Nikon digital SLR.

- Micro. Nikon uses the term micro to designate its close-up lenses. Most other vendors use macro instead.

- N (Nano Crystal Coat). Nano Crystal lens coating virtually eliminates internal lens element reflections across a wide range of wavelengths, and is particularly effective in reducing ghost and flare peculiar to ultra-wide-angle lenses. Nano Crystal Coat employs multiple layers of Nikon’s extra-low refractive index coating, which features ultra-fine crystallized particles of nano size (one nanometer equals one millionth of a mm).

- NAI. This is not an official Nikon term, but it is widely used to indicate that a manual focus lens is Not-AI, which means that it was manufactured before 1977, and therefore cannot be used safely on modern digital Nikon SLRs (other than the retro Df model) without modification.

- NOCT (Nocturnal). Used primarily to refer to the prized Nikkor AI-S Noct 58mm f/1.2, a “fast” (wide aperture) prime lens, with aspherical elements, capable of taking photographs in very low light.

- PC (Perspective Control). A PC lens is capable of shifting the lens from side to side (and up/down) to provide a more realistic perspective when photographing architecture and other subjects that otherwise require tilting the camera so that the sensor plane is not parallel to the subject. Older Nikkor PC lenses offered shifting only, but more modern models, such as the PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED lens introduced early in 2008 allow both shifting and tilting.

- UV. This term is applied to special (and expensive) lenses designed to pass ultraviolet light.

- UW. Lenses with this designation are designed for underwater photography with Nikonos camera bodies, and cannot be used with Nikon digital SLRs.

- VR. Nikon has an expanding line of vibration reduction (VR) lenses, including several very affordable models and the AF-S DX Nikkor 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR lens, which shifts lens elements internally to counteract camera shake. The VR feature allows using a shutter speed up to four stops slower than would be possible without vibration reduction, according to Nikon.

Zoom or Prime?

When selecting between zoom and prime lenses, there are several considerations to ponder. Here’s a checklist of the most important factors. I already mentioned image quality and maximum aperture earlier, but those aspects take on additional meaning when comparing zooms and primes.

- Logistics. As prime lenses offer just a single focal length, you’ll need more of them to encompass the full range offered by a single zoom. More lenses mean additional slots in your camera bag, and extra weight to carry. Just within Nikon’s line alone you can choose from a good selection of general-purpose (if you can count AF lenses that won’t autofocus with the D500 as “general purpose”) prime lenses in 28mm, 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, 100mm, 135mm, and 200mm focal lengths, all of which are overlapped by the 18-200mm zoom I mentioned earlier. Even so, you might be willing to carry an extra prime lens or two in order to gain the speed or image quality that lens offers.

- Image quality. Prime lenses usually produce better image quality at their focal length than even the most sophisticated zoom lenses at the same magnification. Zoom lenses, with their shifting elements and f/stops that can vary from zoom position to zoom position, are in general more complex to design than fixed focal length lenses. That’s not to say that the very best prime lenses can’t be complicated as well. However, the exotic designs, aspheric elements, and low-dispersion glass can be applied to improving the quality of the lens, rather than wasting a lot of it on compensating for problems caused by the zoom process itself.

- Maximum aperture. Because of the same design constraints, zoom lenses usually have smaller maximum apertures than prime lenses, and the most affordable zooms have a lens opening that grows effectively smaller as you zoom in. The difference in lens speed verges on the ridiculous at some focal lengths. For example, the 18-55mm super-bargain kit lens gives you a 55mm f/5.6 lens when zoomed all the way out, while prime lenses in that focal length commonly have f/1.8 or faster maximum apertures. If you require speed, a fixed focal length lens is what you should rely on. Figure 7.6 shows an image taken with the Nikon 105mm f/1.4 lens.

- Speed. Using prime lenses takes time and slows you down. It takes a few seconds to remove your current lens and mount a new one, and the more often you need to do that, the more time is wasted. If you choose not to swap lenses, when using a fixed focal length lens, you’ll still have to move closer or farther away from your subject to get the field of view you want. A zoom lens allows you to change magnifications and focal lengths with the twist of a ring and generally saves a great deal of time.

Figure 7.6 A 105mm f/1.4 lens was perfect for this hand-held photo at a concert featuring Raul Malo of the Mavericks.

Categories of Lenses

Lenses can be categorized by their intended purpose—general photography, macro photography, and so forth—or by their focal length. The range of available focal lengths is usually divided into three main groups: wide angle, normal, and telephoto. Prime lenses fall neatly into one of these classifications. Zooms can overlap designations, with a significant number falling into the catch-all, wide-to-telephoto zoom range. This section provides more information about focal length ranges, and how they are used.

When the 1.5X crop factor (mentioned at the beginning of this chapter) is figured in, any lens with an equivalent focal length of 10mm to 16mm is said to be an ultra-wide-angle lens; from about 16mm to 28mm is said to be a wide-angle lens. Normal lenses have a focal length roughly equivalent to the diagonal of the film or sensor, in millimeters, and so fall into the range of about 30mm to 40mm on a D500. Short telephoto lenses start at about 40mm to 70mm, with anything from 70mm to 250mm qualifying as a conventional telephoto. For the Nikon D500, anything from about 300mm to 400mm or longer can be considered a super-telephoto.

Using Wide-Angle and Wide-Zoom Lenses

To use wide-angle prime lenses and wide zooms, you need to understand how they affect your photography. Here’s a quick summary of the things you need to know.

- More depth-of-field. Practically speaking, wide-angle lenses offer more depth-of-field at a particular subject distance and aperture. You’ll find that helpful when you want to maximize sharpness of a large zone, but not very useful when you’d rather isolate your subject using selective focus (telephoto lenses are better for that).

- Stepping back. Wide-angle lenses have the effect of making it seem that you are standing farther from your subject than you really are. They’re helpful when you don’t want to back up, or can’t because there are impediments in your way.

- Wider field of view. While making your subject seem farther away, as implied above, a wide-angle lens also provides a larger field of view, including more of the subject in your photos.

- More foreground. As background objects retreat, more of the foreground is brought into view by a wide-angle lens. That gives you extra emphasis on the area that’s closest to the camera. Photograph your home with a normal lens/normal zoom setting, and the front yard probably looks fairly conventional in your photo (that’s why they’re called “normal” lenses). Switch to a wider lens and you’ll discover that your lawn now makes up much more of the photo. So, wide-angle lenses are great when you want to emphasize that lake in the foreground, but problematic when your intended subject is located farther in the distance.

- Super-sized subjects. The tendency of a wide-angle lens to emphasize objects in the foreground, while de-emphasizing objects in the background can lead to a kind of size distortion that may be more objectionable for some types of subjects than others. Shoot a bed of flowers up close with a wide angle, and you might like the distorted effect of the larger blossoms nearer the lens. Take a photo of a family member with the same lens from the same distance, and you’re likely to get some complaints about that gigantic nose in the foreground.

- Perspective distortion. When you tilt the camera so the plane of the sensor is no longer perpendicular to the vertical plane of your subject, some parts of the subject are now closer to the sensor than they were before, while other parts are farther away. So, buildings, flagpoles, or NBA players appear to be falling backward, as you can see in Figure 7.7. While this kind of apparent distortion (it’s not caused by a defect in the lens) can happen with any lens, it’s most apparent when a wide angle is used.

- Steady cam. Hand-holding a wide-angle lens at slower shutter speeds, without vibration reduction, produces steadier results than with a telephoto lens. The reduced magnification of the wide-lens or wide-zoom setting doesn’t emphasize camera shake like a telephoto lens does.

- Interesting angles. Many of the factors already listed combine to produce more interesting angles when shooting with wide-angle lenses. Raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting. The same change in elevation can produce a dramatic effect for the much-closer subjects typically captured with a wide-angle lens or wide-zoom setting.

Avoiding Potential Wide-Angle Problems

Wide-angle lenses have a few quirks that you’ll want to keep in mind when shooting so you can avoid falling into some common traps. Here’s a checklist of tips for avoiding common problems:

- Symptom: converging lines. Unless you want to use wildly diverging lines as a creative effect, it’s a good idea to keep horizontal and vertical lines in landscapes, architecture, and other subjects carefully aligned with the sides, top, and bottom of the frame. That will help you avoid undesired perspective distortion. Sometimes it helps to shoot from a slightly elevated position so you don’t have to tilt the camera up or down.

- Symptom: color fringes around objects. Lenses are often plagued with fringes of color around backlit objects, produced by chromatic aberration, which is produced when all the colors of light don’t focus in the same plane or same lateral position (that is, the colors are offset to one side). This phenomenon is more common in wide-angle lenses and in photos of subjects with contrasty edges. Some kinds of chromatic aberration can be reduced by stopping down the lens, while all sorts can be reduced by using lenses with low diffraction index glass (or ED elements, in Nikon nomenclature) and by incorporating elements that cancel the chromatic aberration of other glass in the lens.

Figure 7.7 Tilting the camera back produces this “falling back” look in architectural photos.

- Symptom: lines that bow outward. Some wide-angle lenses cause straight lines to bow outward, with the strongest effect at the edges. In fisheye (or curvilinear) lenses, this defect is a feature, as you can see in Figure 7.8, the otherwise difficult-to-capture interior of a cramped barracks at Fort Matanzas, in Florida. When distortion is not desired, you’ll need to use a lens that has corrected barrel distortion. Manufacturers like Nikon do their best to minimize or eliminate it (producing a rectilinear lens), often using aspherical lens elements (which are not cross-sections of a sphere). You can also minimize barrel distortion simply by framing your photo with some extra space all around, so the edges where the defect is most obvious can be cropped out of the picture. Some image editors, including Photoshop and Photoshop Elements and Nikon Capture NX-D, have a lens distortion correction feature.

- Symptom: dark corners and shadows in flash photos. The Nikon D500’s optional electronic flash is designed to provide even coverage for lenses as wide as 17mm. If you use a wider lens, you can expect darkening, or vignetting, in the corners of the frame.

Figure 7.8 Many wide-angle lenses cause lines to bow outward toward the edges of the image; with a fisheye lens, this tendency is considered an interesting feature.

Using Telephoto and Tele-Zoom Lenses

Telephoto lenses also can have a dramatic effect on your photography, and Nikon is especially strong in the long-lens arena, with lots of choices in many focal lengths and zoom ranges. You should be able to find an affordable telephoto or tele-zoom to enhance your photography in several different ways. Here are the most important things you need to know. In the next section, I’ll concentrate on telephoto considerations that can be problematic—and how to avoid those problems.

- Selective focus. Long lenses have reduced depth-of-field within the frame, allowing you to use selective focus to isolate your subject. You can open the lens up wide to create shallow depth-of-field, or close it down a bit to allow more to be in focus. The flip side of the coin is that when you want to make a range of objects sharp, you’ll need to use a smaller f/stop to get the depth-of-field you need. Like fire, the depth-of-field of a telephoto lens can be friend or foe. Figure 7.9 shows a photo of a merry-go-round horse shot with a 200mm lens and a wider f/2.8 f/stop to de-emphasize the distracting background.

Figure 7.9 A wide f/stop helped isolate the merry-go-round horse, while allowing the background to go out of focus.

- Getting closer. Telephoto lenses bring you closer to wildlife, sports action, and candid subjects. No one wants to get a reputation as a surreptitious or “sneaky” photographer (except for paparazzi), but when applied to candids in an open and honest way, a long lens can help you capture memorable moments while retaining enough distance to stay out of the way of events as they transpire.

- Reduced foreground/increased compression. Telephoto lenses have the opposite effect of wide angles: they reduce the importance of things in the foreground by squeezing everything together. This compression even makes distant objects appear to be closer to subjects in the foreground and middle ranges. You can use this effect as a creative tool to squeeze subjects together. You’ll find the effect used all the time in TV shows, where the hero dashes toward the camera while racing between slow-moving automobiles, seemingly each just a foot or two apart.

- Accentuates camera shakiness. Telephoto focal lengths hit you with a double whammy in terms of camera/photographer shake. The lenses themselves are bulkier, more difficult to hold steady, and may even produce a barely perceptible see-saw rocking effect when you support them with one hand halfway down the lens barrel. Telephotos also magnify any camera shake. It’s no wonder that vibration reduction is popular in longer lenses.

- Interesting angles require creativity. Telephoto lenses require more imagination in selecting interesting angles, because the “angle” you do get on your subjects is so narrow. Moving from side to side or a bit higher or lower can make a dramatic difference in a wide-angle shot, but raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting.

Avoiding Telephoto Lens Problems

Many of the “problems” that telephoto lenses pose are really just challenges and are not that difficult to overcome. Here is a list of the seven most common picture maladies and suggested solutions.

- Symptom: flat faces in portraits. Head-and-shoulders portraits of humans tend to be more flattering when a focal length of 50mm to 85mm is used. Longer focal lengths compress the distance between features like noses and ears, making the face look wider and flat. A wide angle might make noses look huge and ears tiny when you fill the frame with a face. So stick with 50mm to 85mm focal lengths, going longer only when you’re forced to shoot from a greater distance, and wider only when shooting three-quarters/full-length portraits, or group shots.

- Symptom: blur due to camera shake. Use a higher shutter speed (boosting ISO if necessary), consider an image-stabilized lens, or mount your camera on a tripod, monopod, or brace it with some other support. Of those three solutions, only the first will reduce blur caused by subject motion; a VR lens or tripod won’t help you freeze a race car in mid-lap.

- Symptom: color fringes. Chromatic aberration is the most pernicious optical problem found in telephoto lenses. There are others, including spherical aberration, astigmatism, coma, curvature of field, and similarly scary-sounding phenomena. The best solution for any of these is to use a better lens that offers the proper degree of correction, or stop down the lens to minimize the problem. But that’s not always possible. Your second-best choice may be to correct the fringing in your favorite RAW conversion tool or image editor. Photoshop’s Lens Correction filter offers sliders that minimize both red/cyan and blue/yellow fringing.

- Symptom: lines that curve inward. Pincushion distortion is found in many telephoto lenses. You might find after a bit of testing that it is worse at certain focal lengths with your particular zoom lens. Like chromatic aberration, it can be partially corrected using tools like the correction tools built into Photoshop and Photoshop Elements. You can see an exaggerated example in Figure 7.10, especially at the edge; pincushion distortion isn’t always this obvious.

- Symptom: low contrast from haze or fog. When you’re photographing distant objects, a long lens shoots through a lot more atmosphere, which generally is muddied up with extra haze and fog. That dirt or moisture in the atmosphere can reduce contrast and mute colors. Some feel that a skylight or UV filter can help, but this practice is mostly a holdover from the film days. Digital sensors are not sensitive enough to UV light for a UV filter to have much effect. So you should be prepared to boost contrast and color saturation in your Picture Controls menu or image editor if necessary.

- Symptom: low contrast from flare. Lenses are furnished with lens hoods for a good reason: to reduce flare from bright light sources at the periphery of the picture area, or completely outside it. Because telephoto lenses often create images that are lower in contrast in the first place, you’ll want to be especially careful to use a lens hood to prevent further effects on your image (or shade the front of the lens with your hand).

- Symptom: dark flash photos. Edge-to-edge flash coverage isn’t a problem with telephoto lenses as it is with wide angles. The shooting distance is. A long lens might make a subject that’s 50 feet away look as if it’s right next to you, but your camera’s flash isn’t fooled. You’ll need extra power for distant flash shots. The Nikon SB-5000 and SB-910 Speedlights, for example, can automatically zoom coverage to illuminate the area captured by a 200mm telephoto lens, with three light distribution patterns (Standard, Center-weighted, and Even).

Figure 7.10 Pincushion distortion in telephoto lenses causes lines to bow inward from the edges.

Telephotos and Bokeh

Bokeh describes the aesthetic qualities of the out-of-focus parts of an image and whether out-of-focus points of light—circles of confusion—are rendered as distracting fuzzy discs or smoothly fade into the background. Boke is a Japanese word for “blur,” and the h was added to keep English speakers from rendering it monosyllabically to rhyme with broke. Although bokeh is visible in blurry portions of any image, it’s of particular concern with telephoto lenses, which, thanks to the magic of reduced depth-of-field, produce more obviously out-of-focus areas.

Bokeh can vary from lens to lens, or even within a given lens depending on the f/stop in use. Bokeh becomes objectionable when the circles of confusion are evenly illuminated, making them stand out as distinct discs, or, worse, when these circles are darker in the center, producing an ugly “doughnut” effect. A lens defect called spherical aberration may produce out-of-focus discs that are brighter on the edges and darker in the center, because the lens doesn’t focus light passing through the edges of the lens exactly as it does light going through the center. (Mirror or catadioptric lenses also produce this effect.)

Figure 7.11 Bokeh is less pleasing when the discs are prominent (top), and less obtrusive when they blend into the background (bottom).

Other kinds of spherical aberration generate circles of confusion that are brightest in the center and fade out at the edges, producing a smooth blending effect, as you can see at bottom in Figure 7.11. Ironically, when no spherical aberration is present at all, the discs are a uniform shade, which, while better than the doughnut effect, is not as pleasing as the bright center/dark edge rendition. The shape of the disc also comes into play, with round smooth circles considered the best, and nonagonal or some other polygon (determined by the shape of the lens diaphragm) considered less desirable.

If you plan to use selective focus a lot, you should investigate the bokeh characteristics of a particular lens before you buy. Nikon user groups and forums will usually be full of comments and questions about bokeh, so the research is fairly easy.

Nikon’s Lens Roundup

The following section represents my personal recommendations on Nikon lenses, based on the more than four dozen lenses I owned in the past and the more than 30 lenses that remain in my collection today. What follows are just my opinions, and descriptions of what has worked for me. If you want lens testing and more detailed qualitative/quantitative data, you’re better off visiting one of the websites devoted to providing up-to-date information of that type. I recommend Bjørn Rørslett’s original Nature Photograph website (which no longer receives updates, but has a lot of information about older lenses) at www.naturfotograf.com, and the newer www.nikongear.com, as well as DPReview at www.dpreview.com.

Here, my goal is simply to let you know the broad range of optics available and help you narrow down your choices from the vast array of lenses offered. Not all of the lenses I mention will be currently available new from Nikon, but all can be readily found in mint used condition.

Generally, I’m not going to cover non-Nikon lenses, primarily because I have stuck to Nikon products for most of my career. While Nikon lenses aren’t always the best in their focal length/speed ranges, they are always near the top and have proved to be dependable and consistent. I’m not going to provide a lot of exact pricing information, as you can easily Google that, and prices have been trending upward for some time. One of my favorite lenses, which I purchased new for $1,300 now lists at $1,800!

The Magic Three

If you cruise the forums, you’ll find the same three lenses mentioned over and over, often referred to as “The Trinity,” “The Magic Three,” or some other affectionate nickname. They are the three lenses you’ll find in the kit of just about every serious Nikon photographer (including me). They’re fast, expensive, heavier than you might expect, and provide such exquisite image quality that once you equip yourself with the Trinity, you’ll never be happy with anything else. One big advantage of these lenses is that they are all full-frame lenses, so if you upgrade from your Nikon D500 to an FX camera, the hefty price you must pay for this collection won’t be wasted.

In recent years, Nikon has replaced the original members of the Magic Three with new lenses, and most recently upgraded the middle lens—the 24-70mm f/2.8—to VR status. I’ve been fortunate enough to own almost all of these lenses, and will describe them for you lovingly. They’re now divided into two kits, the original trio, which I describe as the Affordable Magic Three—because all of them are still readily available, and at much lower prices than the new, reigning magic lineup.

The Original Magic Three

For a significant number of years, the most commonly cited “ideal” lenses for “serious” Nikon digital SLRs were the 17-35mm f/2.8, 28-70mm f/2.8, and 70-200 f/2.8 VR. (See Figure 7.12.) The trio share a number of attributes. All three are non-DX lenses that (theoretically) work equally well on film cameras, the full-frame models like the D810 and D5, as well as advanced DX cameras like the D500 for those who could justify their cost, making for a sound investment in optics that could be used on any Nikon SLR, past or future. Indeed, I owned all three well before I bought my first full-frame digital Nikon, as my purchases pre-dated the introduction of the original Nikon D3 and D700 models.

Figure 7.12 The “affordable” Magic Three lenses.

All three incorporate internal Silent Wave motors and focus incredibly fast. They all have f/2.8 maximum apertures that are constant; they don’t change as the lens is zoomed in or out. All three are internal focusing (IF) models that don’t change length as they focus, and include extra-low dispersion (ED) elements. And, all three are expensive, at $1,000 to $1,600 each, whether you manage to find one new or, more likely, in mint used condition. But, as I discovered when I added this set, once you have them, you don’t need any other lenses unless you’re doing field sports like football or soccer, extreme wide-angle, or close-up photography. When these three were my primary lenses, I took them with me everywhere, adding another lens or two as required for specialized needs. If you can’t find a new AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8G IF-ED of the VR I variety, Nikon has introduced an f/4 version that, too, is available for an affordable price, and I’ll describe it later in this chapter.

- AF-S Zoom-Nikkor 17-35mm f/2.8D IF-ED. When I am shooting landscapes, doing street photography, or some types of indoor sports, this lens can go on my camera and never come off, even though I also own its nominal replacement, the AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8G ED. Its actual direct replacement, in terms of focal length range and size, is the AF-S Nikkor 16-35mm f/4G ED VR. The newer lens is slower at f/4 instead of f/2.8, but adds VR as an equalizer. The 17-35mm is known to have autofocus motor problems (although my copy has been trouble-free), so if you buy this lens used and find one with a motor that has been recently replaced, that’s a plus. I kept this lens after I got the 14-24mm zoom, because I find I need its 24-35mm focal length range more often than I need the 14-17mm range of the latter lens. I don’t need to swap out for a longer lens as often, and, as a bonus, the 17-35mm lens accepts 77mm filters if I need them, and has an actual old-school aperture ring. I’ll keep this member of the Affordable Magic Three forever.

- AF-S Zoom-Nikkor 28-70mm f/2.8D IF-ED. Nicknamed “The Beast” because of its size and weight, this lens, too, is wonderfully sharp, and well-suited for anything from sports to portraiture that falls within its focal length lens. I know many photographers who aren’t heavily into landscapes who use this lens as their main lens. With its impressive lens hood mounted, The Beast is useful for terrifying small children, too. I eventually sold mine and replaced it with the newer 24-70mm f/2.8 lens described later. This one is just as good as its replacement, and it, too, sports an aperture ring that’s not really essential these days.

- AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8G IF-ED. This legendary lens is perfect for some indoor and many outdoor sports, on a monopod, or hand-held, and can be used for portraiture, street photography, wildlife (especially with the 1.4X teleconverter), and even distant scenics. I use it for concerts, too, alternating between this lens and my 85mm f/1.4. It takes me in close to the performer, and can be used wide open or at f/4 with good image quality. The only time I leave it behind is when I need to travel light (although it’s not really that huge). This is the only lens of the magic trio that lacks an aperture ring, but you probably won’t be using it with a bellows extension, anyway.

The original AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8G IF-ED is typical of the VR lenses Nikon offers. Like the newer model, it has the basic controls shown in Figure 7.13, top left, to adjust focus range (full, or limited to infinity down to 2.5 meters); VR On/Off; and Normal VR/Active VR (the latter an aggressive mode used in extreme situations, such as a moving car). Not visible (it’s over the horizon, so to speak) is the M/A-M focus mode switch, which allows changing from autofocus (with manual override) to manual focus. There’s also a focus lock button near the front of the lens (see Figure 7.13, bottom left). I often use the rotating tripod mount collar, which helps take some stress off the camera lens mount, as a grip for the lens when shooting hand-held, and, as you can see in Figure 7.13, right, I’ve replaced the factory tripod mounting foot with Kirk’s Arca-Swiss-compatible quick-release mount foot.

Figure 7.13 On the Nikon 70-200mm VR zoom you’ll find (top left): the focus limit switch, VR on/off switch, and Normal/Active VR adjustment. The lens also includes an autofocus lock button that can be activated while holding the lens (bottom left). Right: The rotating collar allows mounting the lens/camera to a tripod in vertical or horizontal orientations—or anything in-between.

FULL-FRAME FOLLY?

The only “problem” with the original 70-200mm lens is that it produces noticeable vignetting and reduced sharpness in the corners at many focal lengths when used on a full-frame camera like the D810. These characteristics tend to vanish when the lens is used on the D500 or with a 1.4X teleconverter. To be honest, I’ve had wonderful results with this lens with my full-frame cameras. I don’t shoot landscapes or brick walls with 70mm to 200mm focal lengths, and for the portrait and fashion work I do, the corners aren’t important. You should keep this “shortcoming” of the original 70-200mm zoom in mind. And, unlike the newer 70-200mm f/2.8 VR II lens, it doesn’t “breathe” (a trait I’ll discuss later).

The Reigning Magic Three

When Nikon introduced the D3 and the original D300, it also debuted two new lenses, an AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8G ED and an AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8G ED lens. (The latter lens was replaced by a version with VR in September 2015.) Both are G-type lenses (they lack an aperture ring), have AF-S focusing, and have constant f/2.8 apertures. In 2009, Nikon announced a replacement for the 70-200mm VR lens, rounding out the Magic Trio with an all-new lineup. Like the original big three, these are all full-frame lenses that work with any DX- or FX-format Nikon camera. (See Figure 7.14.)

Other than some minor (and major) sharpness tweaks, one chief advantage of the new lineup (if you can call it that) is that there is no overlap. You can go from 14-24mm to 24-70mm to 70-200mm with no gaps in coverage. I don’t find that an overwhelming advantage, because there are lots of situations in which the 17-35mm range of my existing lens is exactly what I need; if I used the “new” trio exclusively, I’d find myself swapping lenses whenever I needed more than a 24mm focal length.

So, I now own both the new 14-24mm f/2.8 zoom and the old 17-35mm f/2.8 lens—and I use them both about equally. The 14-24mm gives me a bit more wide-angle perspective than the 17-35mm lens, and it is fabulously sharp. I use the 17-35mm lens when I think I’ll need the longer focal length, when I want to shoot semi-macro pictures of, say, flowers, and when I am traveling light. For example, when shooting in Europe I take along the 17-35mm lens (which is much smaller than the 14-24mm, and can be used with polarizing filters, to boot) and my 28-200mm zoom (described later).

Figure 7.14 The reigning Magic Three.

Carefully consider the focal lengths you need before deciding which “magic” triad is best for you. The new lineup looks like this:

- AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8G ED. I own this lens, and its image quality is incredible, with very low barrel distortion (outward bowing at the edges) and very little of the chromatic aberrations common to lenses this wide. Because it has full-frame coverage, it’s immune to obsolescence. It focuses down to 10.8 inches, allowing for some interesting close-up/wide-angle effects. The downside? The outward curving front element precludes the use of most filters, although I haven’t tried this lens with add-on Cokin-style filter holders, including one very expensive ($200) Lee Kit-SW150 Super Wide Filter Holder, which uses 150mm × 170mm and 150mm × 150mm filters. Usually, lack of filter compatibility isn’t a fatal flaw for most users, as the use of polarizers, in particular, would be problematic at wider focal lengths. The polarizing effect would be highly variable because of this lens’s extremely wide field of view.

- AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8G ED. This lens seems to provide even better image quality than the legendary Beast, especially when used wide open or in flare-inducing environments. (You can credit the new internal Nano Crystal Coat treatment for that improvement.) My recommendation is that if you already own The Beast, or can get one used for a good price ($1,200 or less), you don’t sacrifice much going with the older 28-70mm lens, and may find the overlap with the 14-24mm lens useful. But if you have the cash and opportunity to purchase this newer lens, you won’t be making a mistake. Some were surprised when it was introduced without the VR feature, but Nikon has kept the size of this useful lens down, while maintaining a reasonable price for a “pro-level” lens. Some have reported a light leakage problem in the lens barrel, associated with the transparent focus scale window. Nikon will fix it for you, but a temporary fix is to cover the window with black tape.

Nikon has also introduced a slightly bulkier version that does include vibration reduction, the AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR, at a lofty price of $2,400 (roughly $500 more than the MSRP for the non-VR version). I haven’t got around to test it yet, and only you can decide if the extra cost is worth it. Indeed, the older lens will probably be reduced in price and eligible for Nikon rebates as the company closes out its inventory.

- AF-S VR II Zoom-Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8G IF-ED. Not a lot to be added about the latest version of this lens, which is a worthy representative of the telephoto zoom range in this “ideal” trio of lenses. It does have better performance in the corners on full-frame cameras, but most of its other attributes remain the same. One aspect that is different is the tendency of this lens to “breathe” when focused at close distances and long focal lengths, as I’ll describe next.

Lenses that Breathe

One difference between the older VR I and newer VR II versions of Nikon is that the newer lens has a tendency to exhibit focus breathing. That is, the effective focal length of the lens changes as you focus closer and closer. This is not a phenomenon that’s unique to the 70-200mm f/2.8 VR II lens; some lens designs breathe, and some don’t. The original 70-200mm f/2.8 VR I lens exhibited much less of this effect, so those who are upgrading to the newer lens may be in for a surprise.

By convention, the advertised focal length of a lens is measured when the lens is focused at infinity. The effective focal length of the original VR I lens when cranked all the way to its maximum and focused at infinity is 196mm, so it’s assigned a nominal focal length of 200mm (just as 2 × 4 lumber doesn’t really measure 2 × 4 inches). The VR II lens at its maximum zoom setting has an effective focal length of 192mm, so it, too, qualifies for the 200mm designation. At their minimum zoom settings, both lenses are close enough to 70mm that either can be described as 70-200mm zooms. This happens to be true whether either lens is focused at infinity or at their closest focusing distances.

However, at the 200mm setting, when either lens is focused at its minimum focus distance, something interesting happens. The original VR I lens has an effective focal length of 182mm—but the VR II lens’s magnification drops to the equivalent of a 135mm lens. (The original lens focuses down to 4.9 feet, while the newer one focuses slightly closer at 4.6 feet.) At the same distance, that’s quite a difference. Most people don’t shoot these lenses at their maximum zoom setting and minimum focus distance—but I do, and I prefer the older lens for a lot of my work. If I’m shooting very close to my subject, I want and expect a lens that performs more like a 200mm telephoto (even if it’s effectively 182mm) than one that acts like a 135mm medium tele. Figure 7.15 shows the difference.

Figure 7.15 The Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 VR I lens at its maximum zoom setting and closest focus distance (left); the 70-200mm f/2.8 VR II lens at the same zoom setting and focus distance.

New Affordable Honorary Magic Three Entry

Nikon has made things even more interesting with an additional “affordable” replacement for the original 70-200mm f/2.8 zoom. The Nikkor AF-S 70-200mm f/4G ED VR lens, priced at about $1,400, is a slower, lower-cost zoom with the same zoom range. It does focus down to 3.3 feet, but, unlike virtually all of Nikon’s “pro” lenses, takes 67mm filters instead of the standard 77mm diameter filters. Plan to buy yourself a 67mm–77mm step-up ring.

This has proved to be a very good lens, indeed. It has the Nano Crystal Coat and Super Integrated multilayer coating, which should reduce ghosting, flare, and internal reflections, along with three extra-low dispersion (ED) elements. The lens has a newer VR system, with a claimed five-stop improvement in camera stabilization, meaning that, theoretically, you could shoot at, say, the 200mm zoom setting with a shutter speed of 1/30th second and achieve the same camera steadiness that you would have gotten at 1/1000th second. Nikon must be confident about the lens’s VR capabilities, as it’s not even furnished with a tripod collar. That’s an optional accessory; the Nikon RT-1 tripod mount ring is priced at around $225. I recommend that; it’s always wisest to center a long lens to your tripod or monopod instead of the camera’s tripod socket.

Wide Angles

Earlier in this chapter I discussed some select Nikon DX-format lenses. If you can afford to purchase any of the FX lenses described in the following sections, your investment will be protected if you upgrade to a full-frame camera. Among its FX lenses, Nikon has an interesting collection of wide-angle prime lenses and zooms, both old and new, that range in price from a few hundred dollars to around $2,000. Here’s a list of some of the key lenses that are readily available. I’ll describe the zooms and prime lenses separately.

Wide Zooms

These lenses include the widest zooms Nikon offers, along with a set of three prime lenses that cover roughly the same focal length range. These zoom lenses are as follows:

- 14-24mm f/2.8G ED AF-S. Simply the sharpest wide-angle zoom ever made (don’t take my word for it: Google), this is a hefty lens that produces an exquisite rectilinear image (virtually no bowed lines), and it’s fast, to boot. Its chief drawback is that it doesn’t take conventional filters, although Lee makes an expensive adapter for square filters, as I mentioned earlier in this chapter. Expect to pay at least $2,000 for this lens, and, if you depend on gradient ND for your landscape photos, you’ll need to add a second wide-angle lens that does accept filters. Or rely on the D500’s HDR capabilities.

- 17-35mm f/2.8D IF-ED. This member of the “affordable” Magic Three is still offered, and, unless you find a mint used copy, isn’t even that affordable. I described its positives earlier. As I said, I use it in tandem with the 14-24mm f/2.8.

- 16-35mm f/4G ED VR AF-S. A tiny bit slower with a constant f/4 maximum aperture, this lens includes VR. For hand-held shots, that means you won’t miss f/2.8 at all. Instead of 1/60th second at f/2.8, you can shoot at 1/30th second at f/4 and expect the same sharpness.

- 18-35mm f/3.5-4.5G ED AF-S. This is a $750 ultra-wide-angle zoom lens for those who don’t want to spend the bucks for the 17-35mm and 16-35mm VR optics. It’s small and light (at just under 14 ounces), and has three aspherical and two ED elements for great image quality.

- 18-35mm f/3.5-4.5D AF IF-ED. Although replaced by the lens above in 2013, this older lens is still available, and much less than the other three wide-to-35mm zooms. It lacks an internal Silent Wave motor and focuses a bit more slowly, and does not have a constant aperture. The maximum f/stop ranges from f/3.5 at the 18mm focal length setting to f/4.5 at 35mm. Many shooters have found this to be an excellent lens for building a modest collection of FX optics on a budget.

Wide Prime Lenses

Many photographers build a nice kit of lenses using only primes rather than zoom lenses. Most of these lenses are compact, light in weight, and fast, with an f/2.8 or better maximum aperture. A large number of us grew up using only prime lenses—we’re the folks you might have seen a few decades ago with two and three cameras around our neck, each outfitted with a different prime lens. We learned quickly how to use “sneaker zoom” to move in closer or to back up to change our field of view without swapping optics. Not all of these lenses are ancient; Nikon has introduced an affordable 28mm f/1.8 lens, and two wide-angle f/1.4 lenses in 24mm and 35mm focal lengths are fairly recent additions.

- 14mm f/2.8D ED AF. This lens has been largely supplanted by the 14-24mm f/2.8 zoom. It’s not much cheaper, weighs two-thirds as much, isn’t quite as sharp—and doesn’t zoom. It does take rear-mounted gelatin filters, however.

- 20mm f/1.8G ED AF-S. This is an $800 full-frame wide angle that works well on the D500, giving you a large maximum aperture that provides a little more selective focus control despite the wide depth-of-field found in lenses of this focal length. In other words, you can throw your backgrounds and/or foregrounds out of focus if you shoot with this lens wide open.

- 20mm f/2.8D AF / 24mm f/2.8D AF / 28mm f/2.8D AF. This is a trio of affordable (around $300 to $600 each) wide prime lenses, all with f/2.8 maximum apertures and AF (non-AF-S) focusing. You won’t need all three, but you might like to pair the 20mm and 28mm lenses to give you a decent wide-angle range, or stake out the middle ground with the 24mm version.