- Adding new customers : Every quarter the CEO sets goals for growth in the number of new customers. To achieve the goals, CEOs must encourage departments to act as follows:

Engineering develops products that customers want to buy.

Marketing generates interest in the company and its products, and siphons out all but the most interested prospective purchasers.

Sales provides the most interested potential customers with a proof of concept and wins hopefully many of these competitive face-offs.

- Increasing revenue per customer : Companies need to retain almost all their customers and encourage them to buy more. To do this, the CEO must coordinate three departments to do the following:

Customer success calls new customers to evaluate how they are using the product, identifying which product functions they find useful, which are not, which don’t work right, and which should be added.

Engineering incorporates this feedback into new versions of the company’s product.

Sales contacts customers before their contract expires to encourage them to renew and to purchase the new products that company built in response to their feedback.

Hiring and motivating top talent: Rapidly growing companies must retain their best talent and hire new talent to tackle the challenge of sustaining rapid growth. To achieve this critical aim, CEOs must manage a process that anticipates the number of people the company will need to hire in each department based on the company’s revenue growth goals. Each department must work with human resources to identify, interview, and hire excellent candidates to fill these roles. At the same time, departments must assess their people, identify the top performers, and make sure they’re motivated and paid enough to keep them happy at the company.

- Scaling the culture globally: The CEO is unable to make all the business decisions in a global company. Scaling the culture is a way for the CEO to create an environment in which talented people can make those decisions in a way that’s consistent with the company’s values. To achieve these aims, CEOs must communicate regularly with the company’s employees around the world. To that end, CEOs should

Send weekly corporate emails to share details of the company’s operations.

Require all employees of a global company founded, say, in France to speak English in all business communications.

Hold quarterly all-hands meetings to celebrate employees who embody the company’s values.

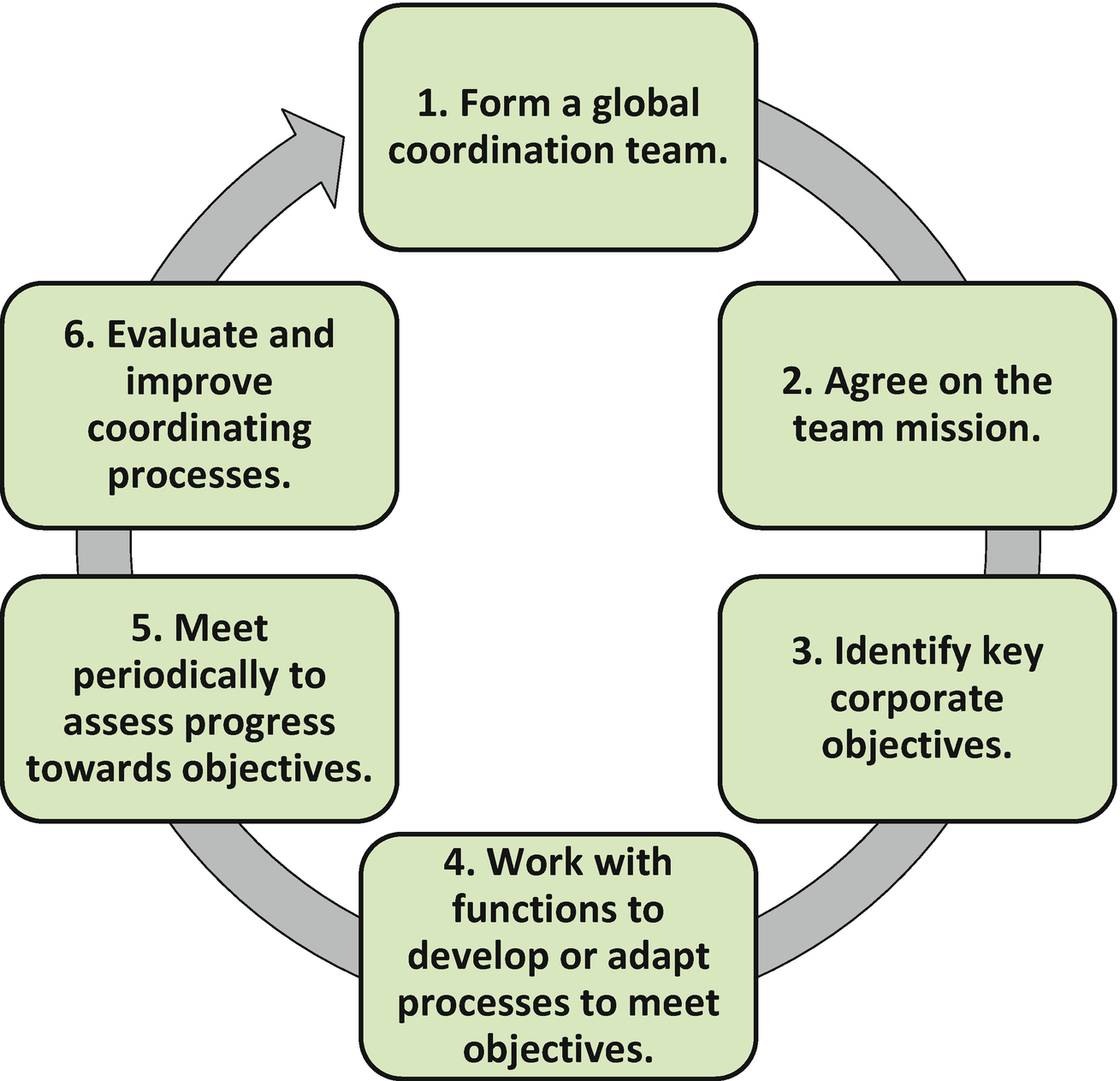

Six steps to coordinating processes

- 1.

Form a global coordination team. The CEO must first assemble a team of key functional executives. The team should consist of the heads of sales, engineering, marketing, service, finance, and human resources.

- 2.

Agree on the team mission. The team should meet to agree on its purpose. A good mission for the team might be to create and improve processes to coordinate functions to achieve the company’s evolving goals.

- 3.

Identify key corporate objectives. After the team has agreed on its mission, the CEO should suggest a set of three to five corporate objectives. These might include specific revenue growth goals, new product initiatives, and plans to expand into new countries. Such corporate objectives would evolve in response to changing customer needs, new technologies, and other factors.

- 4.

Work with functions to develop or adapt processes to meet objectives. The heads of the functions should propose processes for coordinating their efforts to meet corporate objectives. Four such processes were outlined above.

- 5.

Meet periodically to assess progress towards objectives. The CEO may delegate to the Chief Operating Officer responsibility for making sure that each of the coordinating processes is operating according to a schedule. The COO will will work closely with the heads of the functions to keep the processes on track.

- 6.

Evaluate and improve coordinating processes. The CEO should reevaluate the business process each quarter or each year, depending on how well the company is meeting its goals. If the company is meeting its goals, then the processes may be fine but could be made more effective through minor tweaks. If the company is not meeting its goals, the processes might need more radical updating. And if the company changes its corporate objectives, some processes might need to be eliminated and other new ones created.

Takeaways for Stakeholders

- CEO

Work with the executive team to set corporate objectives.

Establish coordinating processes to achieve corporate objectives.

Supervise the coordinating processes or delegate that supervision to the Chief Operating Officer.

Evaluate and improve the effectiveness of the coordinating processes.

- Functional executives

Take responsibility for achieving departmental performance indicators.

Define roles of employees in processes.

Collaborate across departments and identify improvement opportunities.

- Employees

Understand and perform activities required to achieve departmental goals.

Assess the effectiveness of the departmental process.

Make recommendations on how to improve the process .

Coordinating Processes Success and Failure Case Studies

In this section, I offer case studies of coordinating processes used by successful and less successful startups at each scaling stage, analyze the cases, and extract principles for helping founders to coordinate processes at each stage.

Stage 1: Winning the First Customers

Engineering <> Marketing: Engineering and marketing ought to discuss what product features the early adopters find the most valuable and why. This will help marketing to identify which groups of customers might be most interested in the product. For a product sold to enterprises, such customers might be more clustered in specific industries or sizes of companies.

Product Management <> Sales: Product management helps sales to close deals by providing updates on product development plans, often in front of potential customers. Sales also tells product management about what product features are of most interest to potential customers.

Product Management <> Engineering: Product management also takes this input from sales and works with engineering to identify the highest priority opportunities for enhancing current products and developing new ones.

Sales <> Marketing: Sales should talk with marketing to share which kinds of leads are most effective and which do not work so that the company can improve the quality of the lead generation process.

Sales <> Engineering: For smaller companies that chose not to create product management roles, sales should communicate with engineering about its challenges and successes in selling the products. These conversations should yield insights about what features help the sales people to close deals, which do not help, and which features are missing,

Success Case Study: Arcadia Data Plans for Growth As It Adds Blue Chip Customers

Introduction

To win its first customers , a startup’s most important task is to solve the right problem much better than rivals do. The right problem is one that both causes potential customers significant “pain,” the solution of which represents a large market, and that your company is better equipped to solve than rivals. If your company builds a better product, it will be easier to sell to win initial customers and, if those initial customers are happy with the product, to win more customers. To achieve this goal , the CEO must manage a process of setting goals, anticipating the resources needed to achieve those goals, monitoring progress, and taking prompt action to repair any deviations from the plan.This comes to mind in considering San Mateo, California-based business analytics service Arcadia Data, which I discussed in Chapter 7.

Case Scenario

Collect new names from inquiries or conference attendees. Arcadia Data’s marketing sought to generate interest in its products. To do that well, marketing identified which groups of potential customers to target. Marketing hosted conferences, got articles written in relevant media outlets, and conducted social media and email marketing campaigns to interest potential customers in the company.

Send company and product information electronically. Arcadia Data’s marketing department automatically emailed documents and videos to potential customers who expressed interest in the company. Marketing analyzed the responses to what Thomas called electronically-qualified leads generated by these emails: the people who opened the emails, clicked on the videos, and read the documents.

Contact electronically-qualified leads by telephone . Arcadia Data’s telesales force contacted the electronically-qualified leads and asked them about their job responsibilities, why they were interested in the company’s products , whether they were considering purchasing products from other companies, and when they expected to make a purchase decision. When those conversations went well, telesales considered them qualified leads.

Forward telesales-qualified leads to the account executive in the right territory. Arcadia Data’s telesales contacted the manager of the territory or a specific account executive and shared the information they learned from their conversations.

Evaluate whether to bid on the deal. If the telesales-qualified lead sounded promising, the account executive designated it a sales-accepted lead. For each of them, the account executive spoke with the potential customer to assess whether the project was real, who the executive sponsor(s) were within the company, and the project budget. If these details suggested that there was a good opportunity for the company, the sales executive deemed it what Thomas referred to as a sales-qualified lead.

Win the bid. For each sales-qualified lead, Arcadia Data assigned resources to develop a proof of concept for the potential customer. If the customer decided that this proof of concept was better than that of the competitors, it asked for Arcadia Data’s proposed terms and checked references. If all that checked out, Arcadia Data won the bid.

Arcadia Data continued to improve its sales/marketing funnel. For example, over time the company learned what conversion rates (e.g., at Stage 2, how many people who received social media messages or email would turn into electronically-qualified leads) to expect at each stage. What’s more, the company made sure it had the right number of telesales people and account executives to follow up on leads and turn the best ones into paying customers. Its marketing department also learned from failure: how to target its social media and email campaigns to surface a higher proportion of electronically-qualified leads; how telesales could boost the number of leads they qualified that turned into paying customers; and when the company lost to competitors, whether the loss was due to fielding the wrong product at too high a price or whether the failure was due to the company’s need to strengthen its reputation.

Case Analysis

Arcadia Data was adding customers rapidly because it offered them a better product. Moreover, its CEO was doing an excellent job of sustaining the company’s growth by managing a formal business planning process : setting specific corporate and departmental goals, tracking actual progress towards the goals, and acting to correct deviations from plan. Moreover, Arcadia Data’s process of attracting potential customer interest and siphoning off all but the best sales leads seemed to be setting the stage for the company to build a scalable business model in the future.

Less Successful Case Study: Molekule Builds a Better Air Purifier but Struggles to Meet Demand

Introduction

What happens to a company that identifies a groundbreaking idea to solve a huge medical problem, but the chief inventor takes 20 years to build a working prototype of the solution? And once that prototype is built, can the inventor’s son and daughter, who have no prior management experience, build and manage a company to satisfy the swell of demand for the product once it is available to the public? These are the questions that come to mind in considering San Francisco-based air purifier provider Molekule.

When he was a baby, Dilip Goswami suffered from asthma and allergies. After 20 years of work, his father, University of Florida mechanical engineer and veteran energy researcher Yogi Goswami, built a prototype of an air purifier that could relieve Dilip’s symptoms. It also formed the basis of Molekule (cofounded in 2014 by CEO Dilip), which took on Honeywell and Dyson in the $33 billion air filter market. Since launching in May 2016, Molekule had been working hard to make enough of its air purifiers to keep up with demand. Its $799 product (annual air filter subscriptions cost $129) had sold out seven times by September 2018. Molekule’s product worked better than standard high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters , which were invented in the 1940s. As Fast Company wrote “Molekule is the world’s first air purifier that destroys pollutants at the molecular level. Its process, called photoelectrochemical oxidation (PECO) , involves shining light onto a filter membrane that has been coated with proprietary nanoparticles, triggering a reaction that breaks down pollutants of any size, including allergens, mold, bacteria, viruses, and carcinogenic volatile organic compounds that concentrate in indoor air.”

The market potential for the PECO-based product was significant. In addition to helping Dilip, Molekule’s product also helped Jaya Rao, Yogi Goswamis’ daughter, who was the company’s cofounder and COO. As Rao told me in a September 2018 interview, “I moved to Tampa and suffered from migraine headaches. I used the prototype my father had developed and a week later my headaches went away.” Molekule helped people in California affected by wildfire smoke in the summer of 2018. Moreover, in August 2018, the company saw a market opportunity in reaching the 80 million Americans with allergies and the 25 million asthma sufferers. My math (I multiplied the total number of allergy and asthma sufferers by Molekule’s prices) suggests that these two groups of customers represent a total addressable market of $83.9 billion in air purifiers and another $13.5 billion in filters.

Case Scenario

Molekule, which had raised $13.4 million in capital by October 2018, began shipping the product in July 2017. As Rao said, “We’ve sold tens of thousands of the devices, more than we originally imagined. We’ve grown from 11 people to 72 to meet demand for the product, which we sell directly to the consumer. We manufacture through a partnership with Foxconn in China.”

Molekule’s 72 people were organized by function , and collaboration across these functions was crucial. As Rao explained, “we were mission driven from our earliest days. We sit in the interviews with every new hire. And we want to create teams of scientists that collaborate with each other. Dilip and I are siblings who collaborate, which is good and bad. But we fill in the gaps. Dilip started working on the core technology ; he is deeper into the technology and is continuously innovating. I communicate with customers because the scientists have trouble getting across the benefits of the product to customers. We have leaders for each of our functions : manufacturing, engineering, R&D, marketing, and customer service. We want to have a flow of value and information across the functions. We need everyone to collaborate because it leads to better outcomes.”

Case Analysis

Molekule took decades to build a product to realize its vision of building a breakthrough in the air purifier industry. While there is a huge market for its product, it is unclear whether the brother and sister who are managing the company have the know-how to turn the company into a large company that will realize its mission. Certainly, the vagueness of the description that Rao provided of its coordinating processes does not inspire confidence that Molekule would be able to scale the company efficiently. As of October 2018, it was unclear whether the company would be able to raise enough capital and attract the management talent needed to realize the company’s vision.

Principles

- Do

Create a formal business planning process.

Use a marketing/sales funnel to increase sales efficiency.

Assess and improve coordinating processes.

- Don’t

Assume that enforcing the right culture is sufficient to sustain rapid growth.

Stage 2: Building a Scalable Business Model

As they seek to sustain rapid growth while becoming more efficient, startups must manage cross-functional processes that bring in new customers, retain existing ones, boost average revenue per customer, and reduce costs. For first-time founders, managing such processes successfully is a significant challenge. Successful startups should approach the challenge with intellectual humility and an eagerness to learn from those who have succeeded in similar situations. With the right mental attitude, such CEOs can make the most of their efforts to build networks of advisors among other CEOs and investors. Moreover, if they can hire functional executives who have had prior success building scalable business models, such founders can learn how to establish and operate such processes effectively.

Success Case Study: Algolia Outdoes Google in Business Search As It Grows Along a Path to Profitability

Introduction

Between 2015 and 2018, I took undergraduate students to visit startups in Paris each spring. Our visits there highlighted a handful of startups that seemed to be coping with their challenges. However, we did not see any companies that had recently raised significant amounts of capital or were aggressively seeking to hire people. However, in May 2018, we visited with a company that was founded in Paris; our visit featured recent college graduates from around the world who had recently joined the company, and they were all speaking to the audience of American students in English. The company in question was Algolia, a San Francisco-based provider of enterprise search services . In an October 2018 interview with Algolia cofounders, I learned that behind its rapid growth was a product that better served its business customers and a willingness to learn the Silicon Valley approach to growing a startup, coupled with its intent to hire the best talent globally and to move towards profitability.

Algolia, which was founded in 2012 in Paris and had raised a total of $74 million by October 2018, was growing fast. According to my October 2018 interview with cofounders CEO Nicolas Dessaigne and CTO Julien Lemoine, by September 2018, its customer count had grown 38% to 5,700 businesses since the start of 2018; annual recurring revenue was expected to more than double to between $40 million and $50 million by year-end, up from $1 million in 2014, $10 million in 2016, and $20 million in 2017; and headcount was expected to soar 33% to 300 by year end from 200 in 2017 and 60 the year before. Algolia was targeting the enterprise search market that was expected to reach $8.9 billion by 2024, according to Grandview Research . And Dessaigne said that this number excluded a significant segment: marketplaces and other business-to-consumer search.

Case Scenario

Algolia was growing rapidly for three reasons: its product was a better solution for businesses; its cofounders were schooled in the Silicon Valley approach to startup growth; and its process for hiring talent was helping to fuel its continued growth as it became more profitable on its path to an IPO. Before meeting Algolia, I thought that Google had the search market sewn up. But there was one segment of the market that Google had abandoned: the business of helping consumers search through a company’s online product catalog. Google was good at bringing users to a website but once there, customers relied on the websites’ own search functions to find products. Some companies built their own engines; others used open-source software , such as Elasticsearch ; and Algolia, which charged clients for its service, rather than selling ads and collecting user data, was rapidly gaining market share by supplying a service that hunted the client’s website and swiftly offered consumers relevant results.

Algolia’s cofounders had been exposed to the Silicon Valley approach to startups via their participation in the famed startup incubator Y Combinator. As we saw in May 2018, Algolia used English in all its offices and sought U.S. clients from the beginning. Dessaigne and Lemoine were in their first time as startup leaders and they were learning some important lessons about how to scale. As Dessaigne said, “We would view an IPO as a funding event . We want to keep the company independent so it can achieve its full potential. It is not about the money, it’s about learning. And one thing we are focused on is finding the right talent in functions like sales, customer success, marketing, and engineering. As you grow bigger, the roles become more specific. For example, we hire account executives for small and medium-sized businesses, middle-market with industry specializations, and enterprise. When we feel the pain, we hire. It’s very humbling. What do we need to learn? Who do we need to hire? We learn from other companies at our stage of development. The reason talent would want to work at Algolia was not the same in October 2018 as it was in its early days.” As Lemoine explained, “We tell candidates to join us for the adventure. The market has unrealized potential; we’ve only tapped 1% of it so far. The entrepreneurial talent we hired in the early days would not join us today. Now we are hiring for a narrower scope. We need experienced people now who have seen this before.”

Algolia was not profitable. As Dessaigne said, “Like many fast SaaS companies our stage, we invest in growth over short term profit. That growth is sustainable and will lead to higher profits in the future.” Algolia was keeping a close eye on the IPO of another company in the business search industry , Elastic , which commercialized open-source software for search and data analytics. Elastic enjoyed 79% revenue growth in the July 2018-ending quarter to $56.6 million and a net loss of $18.6 million. And its stock price soared 94.4% on its first day of trade, October 5, 2018. Would Algolia sustain its growth rate long enough to go public in 2020?

Case Analysis

Unlike other Parisian startups I’ve visited, Algolia was growing rapidly on a path to profitability . In addition to providing a better solution to the problem of business search, its growth was attributable to the intellectual humility of its cofounders. This mindset enabled them to fill in the gaps in their knowledge and experience as they tried to sustain an annual doubling of revenue, hire the talent needed to sustain that growth pace, and make its operations more sustainable. Algolia was growing mostly due to the competitive superiority of its product, almost in spite of its less-than-fully developed business processes. While it appeared to be eager to hire and motivate talented people around the world and efficiently bring in new customers, retain existing ones, and sell them more. Algolia’s leaders seemed to be learning how to coordinate its processes efficiently.

Less Successful Case Study: After Eight Years, Kinetica Hires a New CEO to Jump-Start Its Growth

Introduction

There’s no guarantee that a company’s founder has what it takes to build a large company. In fact, some 60% of founders do not survive their Series D round of venture funding. This comes to mind in considering San Francisco-based database supplier Kinetica . Founded in 2009, Kinetica raised $50 million in June 2017, bringing its total funding to $63 million. Six months later, Kinetica’s board replaced cofounder and CEO Amit Vij with Paul Appleby, an experienced sales executive. Kinetica said that its technology “combined artificial intelligence and machine learning, data visualization and location-based analytics, and the accelerated computing power of a GPU [graphical processing units made by the likes of Nvidia to run video games] database.” Kinetica built relationships with companies and technology partners to bring this idea to life. Kinetica’s customers came from industries including healthcare, energy, telecommunications, retail, and financial services. And its technology and marketing partners included NVIDIA, Dell, HP, and IBM.

The brains behind Kinetica were Vij and his Kinetica co-founder, Nima Negahban. As Fortune wrote, “They worked at the United States Army Intelligence and Security Command and the National Security Agency creating a system to track and capture terrorists in real time. The U.S. Postal Service has used Kinetica since 2014 in a system that optimizes routes and tracks packages.” Vij lost the top spot at Kinetica to Appleby in December 2017. The company was looking for “sales momentum ” and Kinetica director Ray Lane seemed to think Appleby fit the bill. Appleby most recently served as President, Worldwide Sales and Marketing at BMC Software (and previously as an executive at Salesforce, C3 IoT, and Siebel Systems). As Lane said in December 2017, “2017 has been a breakout year for Kinetica, doubling headcount while it onboards and grows new customers and partners around the globe. There is considerable demand today for Kinetica’s speed and capabilities produced by its native GPU-accelerated , in-memory architecture. Paul recognizes the strategic nature of the enterprise data challenges Fortune 2000 companies face and how Kinetica can accelerate real-time insights from any data sources, regardless of volume, velocity, and structure. Paul’s proven experience leading global growth teams, plus the drive to take Kinetica to the next level, makes him a unique choice for Kinetica.”

Case Scenario

Appleby delivered growth. As he said in a September 2018 interview, “At the beginning of the year we had 70 to 80 people and now we have 110. In the first half of 2018, we grew bookings 156% and the number of net new customers by 190%. A significant number of our existing customers are expanding their relationship with Kinetica. We could grow [with a scalable business model].” To get Kinetica to the next level, Appleby organized the company by function. “We’re an innovation-driven company, and most of our employees, two-thirds of the company, are engineering and innovation-focused. Almost half of our employees are based out of our Arlington, Virginia engineering office. Our administrative, finance, and marketing functions are San Francisco-based, and our sales team is distributed across Europe, Asia, and the United States,” he said. Appleby believed that everyone who worked with a company, including its leadership, employees, and partners, should be “aligned to a common set of strategic goals and objectives. As such, creating an environment where all parties felt ownership of the company strategy and alignment to that is a top priority. Our objectives span product, ecosystem, customer success, and culture. We use them to formulate our employees’ MBOs [Management by Objectives ], and to guide our company direction holistically.”

He chaired Kinetica’s Executive Leadership Team (ELT) which included executives from its “product development, customer success, sales, marketing, and finance [functions]. ELT meets regularly to plan, track, and execute on our key objectives. Every member of the team has detailed dashboards that map to key metrics that measure progress towards our objectives.” Kinetica held everyone accountable for results. “On a quarterly basis, our executive team determines key outcomes we want to achieve, in accordance with our strategic objectives. These leaders then meet with their teams and determine MBOs for each employee that help us meet those objectives. The MBOs change each quarter, but they are always formulated to meet our strategic goals,” Appleby told me, “Everybody in the company knows how their success will be measured. As he said, “We link metrics and objectives by following the Objectives & Key Results (OKR) model used by Facebook, Amazon, and Salesforce. The metrics, or key results, are in place at company, departmental and individual levels to gauge progress. Each employee has a specific set of measurable, quarterly MBOs that act as the metrics to track progress towards our company objectives.”

Kinetica’s MBOs seemed much more specific and measurable than its goals/objectives, which were meant to inspire. For example, Appleby said one of the company’s objectives was “change the world by helping companies innovate and transform in the post-big data world.” Two MBOs associated with that objective seem to drive people to find good sales leads and achieve high customer retention. The first MBO was “identify the number of companies that are tackling new initiatives. This gives us an indication that companies can use our technology to drive their business forward as we enter the extreme data economy.” The second was to achieve “high customer retention rates [which] give us a way to show we’re delivering value and are critical to our customers’ business,” he said.

Case Analysis

In less than a year after having taken over as CEO of Kinetica , Appleby had demonstrated his ability to accelerate the company’s revenue growth. Moreover, he had established clear goals, a clearly articulated process for making people accountable, and the hope that Kinetica’s organization would be able to achieve the ambitious goals he set. However, Kinetica’s processes for bringing in new customers, retaining and selling more to existing customers, and making its operations more efficient were unclear in October 2018.

Principles

- Do

Establish a process for understanding customer pain and building products that relieve that pain better than competitors’ products.

Manage the process of attracting, motivating, and retaining the best talent for key jobs.

Maintain intellectual humility and a deep commitment to admitting areas of ignorance and building professional networks to close the knowledge gaps.

- Don’t

Hold on too long to a technical CEO who lacks the ability to set aggressive growth goals and drive the company to achieve them.

Stage 3: Sprinting to Liquidity

Success Case Study: JFrog Sprints to Liquidity with a Scalable Business Model

Introduction

A startup that helped software developers to deliver software updates to customers was growing so rapidly after a decade in operation that investors valued it at over $1 billion as the company sprinted to liquidity. The company solved a common problem: almost everything people did at home or work was powered by software. But not too long after getting that software, it stopped working as well as it should. How so? Hackers exploited its weaknesses, it took too long to open pages or to respond after a user clicked on a button, it didn’t work right when a user bought a new device or installed a new app, and if the user tried to retrieve things from the cloud, it took too long before responding. Delivering software as a service, in which fixes were sent to users a few times a day, helped solve these problems. But the software developers had a big problem of their own: the process of creating and updating software was fraught with problems: it was expensive, slow, and vulnerable to hackers. Not surprisingly, there was a big business, dubbed DevOps (short for development operations), to solve this problem. It was a $50 billion market populated by some big companies like Google , Microsoft (which acquired GitHub for $7.5 billion), and Amazon as well as many smaller companies such as Atlassian, which has enjoyed an 88% rise in its stock as of October 2018.

And one of those, 10-year-old Mountain View, California-based JFrog , raised a whopping $165 million on October 4, 2018 to continue outpacing these big rivals. JFrog’s so-called liquid software allowed its customers to deliver code in the form of binaries so they could distribute it regularly behind the scenes without impinging on the user experience. JFrog, which had raised a total of $226.5 million and was valued way north of $1 billion in October 2018, had grown rapidly in the previous two years. Between January 2016, when it raised its $50 million Series C funding, and October 2018, JFrog said its sales had grown over 500%. It had more than 4,500 customers , including more than 70% of the Fortune 100—including Amazon, Facebook, Google, Netflix, Uber, VMware, and Spotify. JFrog was popular with developers. The company said it added 100 new corporate customers a month and its so-called Bintray binary hub , a place to store, monitor, and send the collection of 1s and 0s, images, sounds, and compressed versions of other files that make computer hardware do its magic, was used by 700,000 open source community projects distributing more than 5.5 million unique software releases that generate over three billion downloads a month.

Case Scenario

JFrog, which had operations in Israel, North America, Europe, and Asia, had grown its staff considerably since it was founded in 2008. According to my October 2018 interview with cofounder and CEO, Shlomi Ben Haim, “We had under five people in 2008 and today we have 400. In 2012, revenues were $2 million, and we will end 2018 with $100 million in revenues.”

Along with its rapid growth, the company had been profitable since 2014. As Ben Haim explained, “We have been cash flow positive since 2014. We did it because we built an efficient funnel [a marketing process to filter out efficiently all but potential customers eager to buy the product]. We did it with zero field sales people. It was all inbound leads converted to buyers by inside sales people. It works because developers don’t like salespeople; they test our product, like it, and adopt it. Developers saw that we are solving their pain; our product became viral.”

JFrog’s people were organized by function, with people in R&D, sales and marketing, and customer success. “JFrog values customer happiness , not satisfaction. We have less than 3% churn. We listen well to our community, which sends us tickets suggesting how to improve the product. We are best of breed on what matters most to the community rather than trying to do everything, as some competitors do. We solve the most urgent customer pain and then launch it,” he said. With its October 2018 capital infusion, JFrog planned to add talent to fuel global expansion . Ben Haim explained, “We plan to grow organically offices around the world, offering a platform with seven solutions. We will build an enterprise field sales force and use the professional services company we acquired. We also plan to acquire companies in the landscape of our technology.” The company said it had a bright future. “Our revenue growth rate is not coming down. We will reach $1 billion in revenue by 2025. An IPO would be a milestone. We are built to last and an IPO is a tool to get there.”

Case Analysis

A decade after its founding, JFrog was clearly sprinting to liquidity. With $100 million in revenue, ample capital, and a business model that enabled it to grow profitably, which had been working since 2014, in October 2018 JFrog was aiming to go public within a few years. JFrog coordinated several important processes that enabled it to grow profitably; most notably, its product development process yielded product improvements driven by direct feedback from its users and the company managed an efficient marketing funnel that produced inbound leads without field sales people—a powerful combination.

Less Successful Case Study: After 10 Years, Virtual Instruments Is Growing at 20% While Hoping to Be Acquired

Introduction

Some CEOs describe their venture backers as patient. But after holding on for a decade, even the most patient venture capitalists can be excused for their eagerness to realize a return on their investment. Such impatience can prompt investors to turn their back on a startup, asking for more capital if its CEO can’t deliver sufficiently rapid revenue growth due to having saturated a small market. Lacking cash, such a CEO would need to shut down or merge. And if the CEO of that merger partner was run by an executive who had previously sold companies that he had led, the investors might be willing to pour in more capital to target a larger market. That is the labyrinthine story of San Jose, California-based Virtual Instruments, a provider of “application-centric infrastructure performance monitoring.” Founded in 2008, it had raised $96.5 million by October 2018.

That incarnation of Virtual Instruments was formed in 2016 when it merged with Load Dynamix, of which Philippe Vincent was CEO. Vincent, a native of France with an MS in Mechanical Engineering from Berkeley and a Harvard MBA, spent 10 years at Accenture where he rose to partner. In 2007, he started as Chief Operating Officer of Big Fix software, a provider of intelligent monitoring of devices and infrastructure for security and compliance issues, which IBM bought for $400 million in July 2010. In 2012, he became CEO of Load DynamiX, which had raised about $19.3 million to simulate and monitor corporate storage workloads. In April 2016, Load DynamiX merged with Virtual Instruments , whose product tapped the flow of information through network equipment (such as Fibre Channel and Ethernet). They merged for two reasons: first, Virtual Instruments had run out of room to grow in its core fibre channel market , which led its investors to turn down another round of investment. Second, customers were installing products from both companies (LoadDynamiX used Virtual Instruments’ product) and wanted them to work together. At the time of the merger, Virtual Instruments’ VirtualWisdom product analyzed the performance of a company’s computing infrastructure, but it was unable to simulate production workloads in its lab, which was where LoadDynamiX’s technology fit in.

Case Scenario

Virtual Instruments grew following the merger, yet it was still refining its processes for product development and marketing . Vincent wanted to accelerate revenue growth from about 20% to above 30%; however, he hinted that being acquired was a more likely outcome than going public. Under Vincent’s leadership, Virtual Instruments has grown since the merger. In an October 2018 interview, he said, “We merged to invest in innovation and to reposition around a larger total addressable market. At the time of the merger, we had 140 employees and we now have 210 plus engineering contractors. We spent 2016 and part of 2017 enhancing the product. In the four quarters since we began selling the product, we have grown in the mid-20% growth rate. We went from 0 to 60 in a year and in 2017 had 173% growth rate in new customers. We are planning on $75 million in revenue for 2018. We expect to boost our growth rate to at least 30% in the future.

Vincent saw a $20 billion addressable market for Virtual Instruments. “Gartner says that the performance and availability space will reach $4.8 billion in 2018, growing to $6.13 billion in 2022. When you add infrastructure monitoring to application monitoring, the business of AppDynamics [which Cisco Systems acquired for $3.7 billion in January 2017 just after it filed for an IPO], to workload automation, you get $20 billion,” he explained. Virtual Instruments won business because it gave companies a single tool built to automate the data center. As Vincent said, “The analogy is to look at the way Google built self-driving cars. Instead of using legacy technologies that solved parts of the problem and trying to make them work together, Google built an integrated system specifically for self-driving cars. We do the same for the data center. VirtualWisdom monitors the entire infrastructure and analyzes and optimizes the performance, utilization, and health of IT infrastructure within the context of the applications running on it.” There was evidence that customers preferred VirtualWisdom to similar products from VMWare, CA, and IBM. Gartner Peer Insights found that of 12 verified reviews by customers, VirtualWisdom (with 4.7/5.0 rating) came out ahead of Computer Associates (4.0 rating), IBM (4.3 rating), and VMware (4.5 rating).

To accelerate its growth, Virtual Instruments was working on its product and improving the way it marketed and sold that product. “The first version of our app-centric version of VirtualWisdom hit the market in April 2018 and it has been adopted well by big customers. We must learn how to take it to market. We are learning,” he said. Virtual Instruments had a multi-pronged marketing strategy . “We are holding a three-day bootcamp so our sales people can understand the value proposition of our new product, focusing on the gaps in competitors’ products and describing how our product closes those gaps. We are partnering with channels and application performance monitoring vendors, VMWare, and change management vendors like ServiceNow,” according to Vincent. By October 2018, Virtual Instruments seemed to me to be looking for an acquisition partner. As Vincent explained, “We don’t know about an IPO. AppDynamics filed for an IPO and Cisco bought it. It’s a $20 billion market and Cisco is building a portfolio through acquisition. Splunk could bring our approach to the hybrid cloud. We believe our principles will carry our growth.” Vincent helped to build BigFix, which IBM acquired. It looks to me like he could sell Virtual Instruments to Cisco or IBM.

Case Analysis

Virtual Instruments expected to reach $75 million in revenue by the end of 2018, and if it could maintain its 20% revenue growth rate, it would be able to reach $100 million in revenue by 2020, 12 years after it was founded. Since $100 million is the informal threshold for taking a company public, were Virtual Instruments to reach that size, it would have reached an important benchmark for success. Yet compared to JFrog, Virtual Instruments was lagging in important ways: its revenue growth rate was much slower, it did not have well-developed processes for setting and achieving goals, it was probably not profitable since its sales force was still learning how to sell its product, and it was unclear whether it would be able to gain enough market share to accelerate its revenue growth rate.

Principles

- Do

Establish a process for understanding customer pain and building products that relieve that pain better than competitors’ products.

Operate a selling process that enables the company to grow rapidly and profitably.

Maintain intellectual humility and a deep commitment to admitting areas of ignorance and building professional networks to close the knowledge gaps.

- Don’t

Develop new products without involving the sales force.

Add products through a merger before building an efficient marketing and sales process.

Stage 4: Running the Marathon

For a company to go public , it usually needs at least $100 million in revenue and to sustain growth of at least 30% a year. Before a company goes public, many founders describe the IPO as a funding event. However, this statement downplays the amount of preparation required to make the company successful after it goes public. After all, a public company CEO must report to shareholders each quarter and make sure that the company complies with all the requirements of being a publicly-traded company. Being public puts pressure on a company to beat investors’ expectations for revenue and profit growth and to increase its forecasts for future quarters every three months. In order to accomplish that, the CEO must create and run processes that make the company’s quarterly results as predictable as possible.

Such processes include the four mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. But after a company goes public, there is one process that often sits above the rest in importance: financial forecasting and reporting. Setting up such a system must begin years before the company goes public so that when public reporting becomes mandatory, its system will have been tested and improved so it will work effectively. Fortunately for companies, there are many services available to support this planning and reporting process. Yet the systems will only work if the data provided to these systems, both the financial goals and the assumptions that underly them (e.g., the number of new customers, the anticipated revenue per customer, the customer retention rates), reflect what people in the business believe are realistic, yet ambitious goals. It is not difficult to imagine that a founder who started a company based on product innovation skill might find it less than appealing to spend time managing this process . Indeed, many founders who remain CEO after a company goes public may choose to delegate this process to a Chief Operating Officer or Chief Financial Officer.

Success Case Study: Okta Goes Public and Keeps Revenue Growing Faster Than 50%

Introduction

If a company can go public and keep growing rapidly thereafter, investors are likely to bid up its value. Underlying such a company’s ability to increase its stock price are processes that reliably yield faster-than-expected growth each quarter. If the company continues to exceed investor expectations for both the most recent quarter and the next one, its stock is likely to keep rising. Sustaining such growth depends on careful management of all seven growth levers discussed in this book. This comes to mind in considering San Francisco-based identity management services provider Okta . In a nutshell, Okta kept companies from letting unwanted people access their computer systems. Okta provided its Okta Identity Cloud , which “lets companies securely connect the right people to the right technology, improving security, employee productivity, and user experience.”

Okta’s stock price responded favorably to its expectations-beating results. As of October 2018, Okta had a record of growth, which as of October 4, 2018 had propelled its stock up by 150% since its April 2017 IPO. Since 2015, its revenues had grown at an 85% annual rate from $41 million in 2015 to $260 million in 2018. It had generated negative free cash flow in each of those years, burning through $37 million worth in 2018. In September 2018 Okta posted better-than-expected results and its shares popped 16%. More specifically, on September 6, 2018 Okta reported a 57% rise in revenues to about $95 million, nearly $10 million more than analysts anticipated, and its loss of 15 cents a share was four cents lower than expected, according to Investors.com. Okta’s forecast for the quarter ending in October also beat expectations. Its revenue forecast of $96.5 million was $7.5 million more than analysts expected while its loss forecast of 11 cents to 12 cents was about six cents better than expectations.

Case Scenario

Okta’s expectations-beating growth came from a product that kept it ahead of its evolving customer needs and its ability to set and achieve ambitious goals for revenue growth and hiring to deliver on those goals. As CEO Todd McKinnon explained in a September 2018 investor call, “Our customer-first focus impacts everything we do: how we design and develop our technology; how we go to market; how we service our customers every day. So as we look at our long-term product strategy, we strive to anticipate what will solve our customer’s business pain points today and over time.” Turning that idea into tangible outcomes was the job of Charles Race, Okta President, Worldwide Field Operations. Since joining Okta in November 2016, he had been responsible for “growing Okta’s addressable market, building a world class delivery capability built on customer and partner success, and driving revenue growth [globally]. [He oversees] worldwide sales, customer success and support, partner ecosystems, field marketing, professional services, and business operations,” according to the company.

One way that Okta executed its strategy was to plan rigorously. As Race explained in an October 2018 interview, “Six months ahead [of the next fiscal year] we use a planning process we call Vision, Methods, Targets. [On my team,] we plan for consolidated growth by product, customer, and expansion into distinct markets. We set metrics such as annual recurring revenue growth, renewal rates, introduction of new product functionality, and adding new partners, and we decide how much of our budget to spend on achieving them.” Okta ranked opportunities so it would feel confident that it could achieve its ambitious growth goals. “We allocate quotas across geographies, prioritizing opportunities based on the growth rate, our competitive position, and the resources we have there. Our go-to-market strategy varies by customer group. We sell to a 100-person company using digital sales, work with partners for small and medium enterprises, and assign field sales people to Global 2000 companies,” he said. Okta’s partner program was very broad. According to Race, “We have technology alliances with Google , Amazon, and VMWare; we go to market with vendors like SailPoint which complement our offerings; we work with systems integrators such as Accenture and Deloitte; we partner with resellers like Active Cyber and CDW; and in countries where we don’t have a presence we work with indirect channels.”

To grow fast enough, Okta sought to bring in new customers and to sell more to existing ones. As he said, “Once we acquire a customer we ask how we can upsell. Our customer success people make sure that customers are getting value; they find out what product functions they’re using and which they’re having trouble deploying. We consider what we can sell by customer segment and by product. We have goals for increasing revenue from existing customers and allocate marketing resources to achieve them.” Okta also anticipated the talent it would need to hire and retain to achieve these goals. “We have a software-as-a-service model , which requires us to plan two three quarters out. And we need lead time to recruit and get up to speed the direct sales and technical resources we think we will need to meet our objectives,” he explained. Because it was growing “57% year on year,” Okta faced an ongoing challenge of hiring enough people with the right skills in the right places and getting them on board in time to minimize the chaos. “To keep growing at that rate, we need to either double the quotas or half the territories [Okta did the latter]. And we hire new people to cover the new territories. That means our new and current sales people get new territories and it takes time for them to get up to speed. Our first quarter is not as productive,” said Race.

Okta believed that it had unlimited growth potential, Race concluded, “We are at the intersection of three megatrends : cloud, mobile, and Internet of Things. To tap that unlimited potential, we have to align our product strategy to international growth opportunities.”

Case Analysis

Okta enjoyed a successful IPO and kept growing faster than investors expected thereafter due to three factors : its product stayed ahead of its customers changing needs, its CEO had hired a skilled executive to manage the processes of setting and achieving ambitious revenue goals, and its ability to hire, motivate, and retain top talent to sustain that growth. Okta’s ability to continue to beat expectations would depend on whether these processes would function even more effectively as the company grew.

Less Successful Case Study: ForeScout Technologies Pays the Price for Lowering Its Growth Expectations

Introduction

There is a dark side to taking public a rapidly-growing company that is consistently unprofitable. If it is unable to sustain expectation-beating growth for the current and future quarters every three months, investors will sell the stock, driving its price down substantially. Even if a company delivers faster-than-expected growth for the recently completed quarter, investors will punish the company should it simultaneously lower its forecast for the current and/or future reporting periods. Investors not only punish such a company in the immediate aftermath of a disappointing report, they also stand ready to punish its shares even more if the company does not resume the desired pattern of beating and raising each quarter. If a company does not recover quickly from a bad quarter, investors will question not only its strategy and talent pool, but the company may also need to look at whether its coordinating processes need repair.

This comes to mind in considering San Jose, California-based ForeScout Technologies, an Internet of Things (IoT) security company that let companies track the growing number of devices connecting to their networks. ForeScout went public in October 2017 and its shares had risen 44% as of October 3, 2018. In its second quarter 2018 report, ForeScout beat analysts’ expectations but lowered its guidance for the quarter. Its revenues were up 35.2%, over $4 million more than analysts expected, while it reported negative EPS of $0.18, which was 19 cents less bad than expected. But not only did ForeScout report negative EPS, it burned through cash, posting a free cash flow margin of negative 12%. The biggest problem for ForeScout was that it lowered its revenue growth forecast. CFO Chris Harms said in an August 2018 investor conference call that the company expected to report 13% revenue growth and a net loss of 11 cents a share. And for the full year, revenue was expected to rise 25% while ForeScout expected EPS of negative 11 cents a share (all figures at the midpoint of the forecast range). Investors did not like this report much; its shares lost 14% of their value in the week following the conference call.

Case Scenario

Was ForeScout’s lower growth forecast a result of focusing on a trend that had peaked? The trend in question was General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) , a European data privacy requirement that forced companies to invest in new technology to avoid paying significant fines for being out of compliance with GDPR, which went into effect in 2018. ForeScout believed that GDPR-like regulation was spreading around the world and would create opportunity for ForeScout to provide companies with real-time data on what was connected to their networks. As CEO Mike DeCesare said in an August 2018 investor conference call, GDPR is driving companies to protect data on corporate networks, a challenge that companies can’t meet unless they know what devices are connected to them. And he believed that the growth in such new devices is growing fast. These include, “nontraditional IoT devices on campus, wired and wireless networks like security cameras, televisions, HVAC controllers, and phones,” he said.

ForeScout hoped that its coordinating processes would help it improve its competitive position. DeCesare, who joined ForeScout in 2015 from Intel/McAfee, believed that as a public company ForeScout ought to raise its game due to the added scrutiny. “After an IPO, your data becomes public. How much you spend on R&D, sales and marketing, and G&A as well as days sales outstanding and cash is subject to a higher level of scrutiny. This forces you to inspect yourself more carefully and to do better,” he said in an October 2018 interview. ForeScout’s primary goal was to maintain a high growth rate. “We set goals for R&D, sales and marketing, and G&A functions all premised on the corporate goal of high top-line growth. Since the IPO we have been growing at least 30% a quarter. To get there, we need new logos, we need to boost the revenue coming from each customer, and we need to hire and motivate new talent,” he said.

To bring in new customers, ForeScout’s engineering, marketing, and sales functions needed to collaborate effectively. As DeCesare said, “Thanks to companies like Salesforce and Facebook, customers expect us to be much more agile, updating our product frequently, and making it easy to use, like Facebook. Engineering must work with customers to quickly evaluate and streamline the product. Marketing is responsible for identifying which 500 of the Global 2000 are the best prospects. Marketing gets the product into the hands of their key people so they can test drive the product. This surfaces opportunities for sales, which participates in bake-offs and closes deals.” To boost the ratio of total revenue from a customer to the amount earned in the original sale, ForeScout coordinated engineering, marketing, and sales. “We sell more as customers add more devices to their networks. We want customers to be successful with our product and we track product quality through our net promoter score, which is in the high 70s,” he said.

Bringing in talent was another crucial process for enabling ForeScout to grow. “Salary and bonus are our biggest costs. We have grown our employee base 80% in the last four years. We want to minimize unwanted attrition and we are as careful about last 100 people we hired as the first 100. I am pushing the hiring decisions down to executives, but I still approve every offer because I want to see the level of talent our managers are bringing in. We need to make sure every person is a good fit and we must reward, recognize, and not lose our top performers,” said DeCesare.

Case Analysis

ForeScout was growing rapidly before it went public. However, in August 2018 it announced that growth would slow down considerably in the quarter ending September 2018. The company’s CEO had succeeded in taking the company public two-and-a-half years after he joined as CEO. He was managing important coordinating processes such as signing up new customers; keeping customers satisfied so they would renew their contracts and buy more of ForeScout’s services; and hiring, motivating, and retaining top talent. Because ForeScout forecast a growth slowdown, investors slashed by over 10% the value of the company . By October 2018, it remained uncertain whether ForeScout had the right strategy, talent, and processes needed to get itself back on the path of regularly exceeding investor expectations and raising guidance every three months.

Principles

- Do

Manage a product development process that keeps the company ahead of rivals in anticipating customer needs and building new products to meet them.

Delegate growth planning to a Chief Operating Officer.

Operate a rigorous process for hiring, motivating, and retaining top talent.

- Don’t

Depend too heavily on unsustainable growth trends.

Coordinating Processes Success and Failure Principles

Summary of the principals for coordinating processes

Scaling Stage | Dos | Don’ts |

|---|---|---|

1: Winning the first customer | Create formal business planning process. Use a marketing/sales funnel to increase sales efficiency. Assess and improve coordinating processes management process. | Assume that enforcing the right culture is sufficient to sustain rapid growth. |

2: Scaling the business model | Establish a process for understanding customer pain and building products that relieve that pain better than competitors’ products. Manage the process of attracting, motivating, and retaining the best talent for key jobs. Maintain intellectual humility and a deep commitment to admitting areas of ignorance and building professional networks to close the knowledge gaps. | Hold on too long to a technical CEO who lacks the ability to set aggressive growth goals and drive the company to achieve them. |

3: Sprinting to liquidity | Establish a process for understanding customer pain and building products that relieve that pain better than competitors’ products. Operate a selling process that enables the company to grow rapidly and profitably. Maintain intellectual humility and a deep commitment to admitting areas of ignorance and building professional networks to close the knowledge gaps. | Develop new products without involving the sales force. Add products through a merger before building an efficient marketing and sales process. |

4: Running the marathon | Manage a product development process that keeps the company ahead of rivals in anticipating customer needs and building new products to meet them. Delegate growth planning to a Chief Operating Officer. Operate a rigorous process for hiring, motivating, and retaining top talent. | Depend too heavily on unsustainable growth trends. |

Are You Doing Enough to Coordinate Processes?

Did you build an executive team charged with creating and operating processes to achieve corporate goals?

Did you engage your functional executives in identifying the mission and objectives of these coordinating processes?

Do you monitor the effectiveness of the coordinating processes?

Do you improve processes that are still essential, eliminate ones that are no longer worth performing, and create new processes to meet new objectives?

Conclusion

Coordinating processes is an essential lever for uniting a company in pursuit of corporate objectives. As a startup goes from an idea to a public company and beyond, it needs to add more coordinating processes, enhance the ones it has created in the past, and eliminate ones that no longer serve an important purpose. All these processes are focused in some way on sustaining a high level of growth. In the first stage of scaling, the most important process coordinates the efforts of marketing, engineering, and sales to develop a product that customers are eager to buy. As the company grows, it must build an efficient process for attracting new customers, retaining existing ones, and providing a broader array of products that yield higher revenues for each customer. As a company sprints to liquidity and goes public, it must ultimately operate a reliable process for planning and achieving aggressive growth goals, while hiring, motivating, and retaining the talent needed to achieve those goals. Chapter 9 concludes the book by presenting a CEO action agenda for startup scaling.