A startup’s ability to attract the best people increases as it becomes more successful. However, if a company’s founding team has enjoyed previous startup success or helped build a new business within a respected company, the quality of the founding team may be perceived as excellent. And that high quality will make it easier to recruit other high-quality team members.

The skills that a startup needs to hire for become more specialized as a company grows, and some individuals can adapt while others can’t. Many founders prefer to promote original team members who have excelled as the startup has grown because these individuals have demonstrated that they can learn new skills and they fit with the culture. But those who can’t go further may leave the firm or find a position where they can contribute effectively.

As a company seeks to build a scalable business model , the CEO must hire from the outside. If people who have been with the firm since the beginning can’t take on bigger jobs, the startup will usually try to hire people who have done the jobs at a company in the industry that enjoyed a successful IPO. Hiring such experienced leaders can have considerable advantages, but can also cause significant problems if the new leaders do not fit the startup’s culture.

As companies specialize by function, they often adopt more specific performance measures . We will examine how startups hold people accountable in Chapter 7. However, as a company scales, it adopts specific goals and systems to measure performance. CEOs can use these systems to identify whom to promote and whom to let go.

CEOs must lead the process of deciding whom to hire, promote, and let go. The CEO’s role changes as the company progresses through the four stages of scaling. In the first stage, the CEO often establishes the interview process and meets with the best candidates, decides how much to pay them, chooses whom to promote and let go, and tells them the news. However, as the company gets larger, the CEO delegates many of these activities to members of the executive team who direct specific functions, and the CEO may only get personally involved in decisions about strategically important individuals.

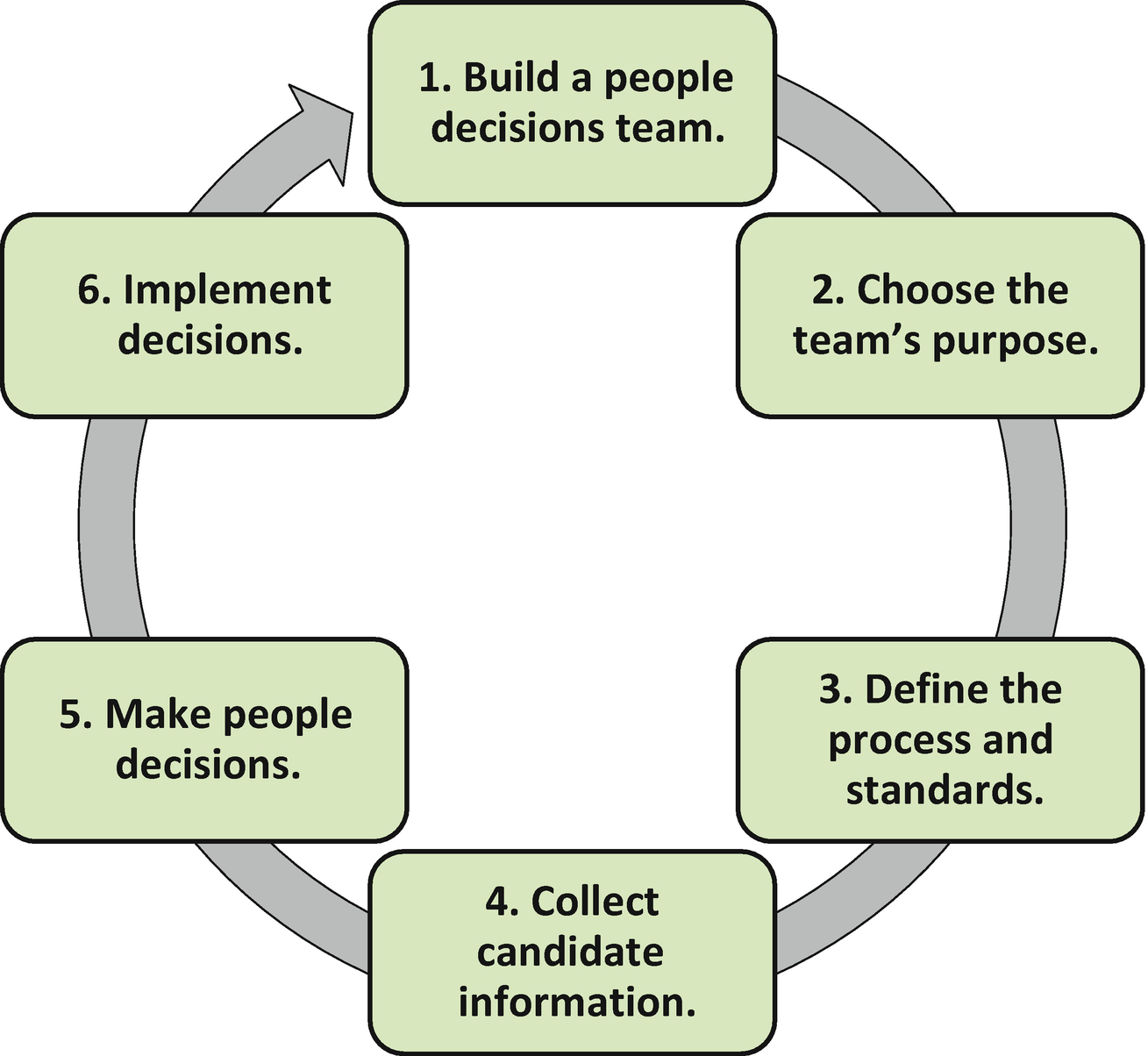

Six steps to hiring, promoting, and letting people go

- 1.

Build a people decisions team . In the first stage of scaling, the CEO will assemble a team of people to interview candidates. Team members usually include leaders of key functions such as product development, sales, marketing, and administration. As the company scales, the hiring teams for lower level positions will be decided on by department heads and may be coordinated by human resources. Decisions about promotions and firing may be made by teams chosen by those department heads. In cases of strategic promotions and firings, the board, CEO, and top executive team may also be involved.

- 2.

Choose the team’s purpose . The CEO will lead the process of gaining consensus on the mission of the people decisions team. To that end, the CEO should articulate the company’s values and vision and incorporate them into the team’s statement of purpose.

- 3.

Define the process and standards . The CEO could ask the people decisions team to propose a process and standards for deciding whom to hire, promote, and let go. The CEO would review the proposal, make suggestions, and modify it based on feedback after the company has used the process to make people decisions.

- 4.

Collect candidate information . The company will gather information about candidates for hiring, promotion, and letting people go. To hire people, the company will seek candidates from internal referrals and job postings, and outside recruiters will interview the best candidates, check references, and offer positions to the ones with the best cultural fit and qualifications. For promotions, the company will speak with people who have worked with the candidate, both inside and outside the company, as appropriate, and make decisions based on the individual’s performance and potential to excel in the new position. In letting people go, the company will also speak with people who have worked with the individual, gathering different information depending on the reason.

- 5.

Make people decisions . Once all the information has been gathered, the people decisions team will meet, discuss what to do, make some decisions, and possibly seek out more information for other decisions.

- 6.

Implement decisions . Ultimately, the company must carry out its people decisions. It will communicate job offers and sign contracts with them; share promotion news including job responsibilities, office location, and compensation; and prepare termination contracts and communicate with employees let go.

Takeaways For Stakeholders

- Board

Identify key roles that must be filled to meet goals.

Refer strong candidates to the CEO.

Offer feedback on most strategic people decisions.

- CEO

Create a people decisions team.

Define vision and values, and incorporate them into the process of hiring, promoting, and letting people go.

Delegate people decisions where appropriate and step in where needed.

- Employees

Refer candidates for new positions.

Apply for promotions and help create new positions that will boost the company’s growth.

Hiring, Promoting, and Letting People Go Success and Failure Case Studies

In this section, I offer case studies of hiring, promoting, and letting people go by successful and less successful startups at each scaling stage, analyze the cases, and extract principles for helping founders to hire, promote, and let people go at each stage.

Stage I: Winning the First Customer

Before a startup can win its first customers, it must win the battle for the most outstandingly qualified cofounders. The best cofounders are essential to winning a startup’s first customers because such leaders have a better chance of finding customers who are willing to help the company design its product and possess the technical skills needed to build a series of ever-better prototypes to make those early customers willing to use and serve as references for the startup’s product.

Passionate about the problem they are trying to solve by starting a company

The most talented product developers or company builders from the most successful companies and the best schools

Well-networked in their industries

At the first stage of scaling, cofounders must attract the best talent they can to solve the many problems required of a company seeking to win its first customers. And cofounders who satisfy these tests have a much better chance of hiring the best talent for achieving the startup’s mission.

Success Case Study: With $173 Million in Capital, Cloudian’s Experienced Team Builds a Scalable Business Model

Introduction

If a startup targets a large market with a product that gives customers more bang for the buck, it has a shot at winning its first customers. Moreover, if the startup wins enough customers under the leadership of its founding team, it may be able to attract considerable private capital to fuel that growth. Indeed, that success should make it easier to attract a team of functional leaders who can help the company build a scalable business model. Once that team is in place, the startup may be able to sprint to liquidity. This comes to mind in considering Cloudian, a San Mateo, California-based distributed file systems purveyor supplying so-called object storage to the $52 billion enterprise storage market, which was growing at a more than 34% annual rate. But Cloudian was growing much faster than the industry, always winning against incumbents like NetApp and EMC when potential customers did a technical evaluation of its product.

Case Scenario

While Cloudian’s business model was not yet scalable, it won customers for three reasons: it spent years building an excellent product for one of the world’s most demanding customers, it started with an excellent technical team, and it was able to hire experienced functional leaders. Cloudian built a product that made a large company very happy and willing to recommend the company to others. “We spent three years making sure that our first customer, [Tokyo-based telecommunications giant] NTT, would be so happy with our product that it would be willing to tell the public about it. We will end 2018 with about 220 people, and to build a scalable business model we are increasing the proportion of revenues through value-added resellers (from 25% in 2016 to 90% in 2017),” said CEO Michael Tso. Cloudian was founded by technically outstanding leaders. For example, one of its cofounders, Hiroshi Ohta, is known in Japan for his engineering prowess. And Tso is an exceptionally talented engineer. He moved from mainland China to Hong Kong and then to Australia for high school. He was accepted at the only school he applied to, MIT, where he earned two BS degrees in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and an MS in Electrical Engineering—all in 1993. He is a prolific inventor. According to Pitchbook, “Tso holds 36 patents and has been a technology trailblazer for over 20 years. At Inktomi, Tso led engineering for an e-commerce search engine, and designed a network congestion control system for KDDI which later became an industry standard. At Intel, he [led the development of] NarrowBand Sockets , commonly known as SmartMessaging , which enabled the world’s first SMS ringtone download service.”

Such experience and excellence made it easier for Cloudian to attract talented functional leaders, particularly as it grew. “Our heads of sales, marketing, customer success, engineering, and finance have all been in the industry for a long time. The team can take us to an IPO, though our investors are very patient,” Tso said. For example, consider Jon Ash, Cloudian’s Vice President of Worldwide Sales. Ash, who was hired into the position in September 2014, was put in charge of Cloudian’s direct and channel sales teams and its systems engineering organization. He had previously been Vice President of Sales at storage software vendor Nexenta . Ash said he was drawn to Cloudian by its “unbeatable value proposition, battle-hardened software platform, compelling appliances, and expanded sales team. Cloudian will introduce enterprises to entirely new levels of scalability, flexibility, and business value from their storage infrastructure.” By August 2018, Ash was still leading Cloudian’s sales, which helped the company to grow to 160 employees and 240 enterprise customers.

Case Analysis

Cloudian did all the right things to win its first customers. It made sure that its product would create value for an influential customer who would be a good reference for potential customers; its cofounders had outstanding technical credentials, which made it easier to attract top talent; it raised a substantial amount of capital; and its initial success made it easier to hire and motivate experienced functional executives who helped propel the company’s growth.

Less Successful Case Study: Sapho Enjoys 320% Growth in a Small Market but Can It Get Large Enough to Go Public?

Introduction

One of the most important decisions a founder makes is which problem the startup will try to solve. The right choice is for the startup to deliver a product that offers customers in a huge market much more value at a lower price than rivals do. The wrong choice is to solve a problem that seems compelling to the founder but not to potential customers. A founder who does that may struggle to build a company large enough to change the world and in so doing may encounter challenges in hiring the people it needs to grow. While such a company may make gradual progress and do its best to overcome the limitations of its relatively small market, long sales cycles, humdrum mission, and less than stellar executive team, it is likely to struggle when it comes to attracting the world’s best talent. That’s what came to mind when I learned about San Bruno, California-based Sapho, which offers a company’s employees “a modern portal experience that surfaces personalized and relevant tasks and data using micro apps,” according to CrunchBase.

Founded in 2014, by September 2018 Sapho had raised nearly $28 million and said it was growing fast as it offered what it claimed was an easier way for employees to engage than did Microsoft SharePoint . Sapho was enjoying rapid percentage growth. As Fouad ElNaggar, cofounder and CEO, explained in a July 2018 interview, “We tripled revenues in 2016, experienced 320% revenue growth in 2017, and are on track to almost quadruple our revenues again in 2018. We have dozens of customers.” Sapho was seeking to operate in a scalable manner. As ElNaggar, who earned an undergraduate degree in economics from Dartmouth and an MBA from UCLA, said, “We are much more focused on building a scalable, profitable business, which means we grow employees at a lower rate than revenues. We have grown our employee base by 50% to 75% per year every year since we started.”

Case Scenario

Sapho’s growth strategy hinged on investing heavily to build its product, delivering measurable economic benefits to customers, managing long sales cycles, and hiring people whom it believed would support its long-term growth. As ElNaggar said, “We’ve invested $30 million over four years to build the patented technology that powers Sapho. Solving the integration, workflow, tooling, deployment, and security challenges in a way that enables our customers to roll out our solution in a compliant way to their entire employee base in a matter of weeks instead of eating up a year took a lot of thought in architecting our solution.”

Sapho made money by charging subscription fees. And given companies’ security and compliance concerns, Sapho took a considerable amount of time to close sales transactions. “It takes us three to six months before we can meet with the Chief Information Officer or high-level IT executive who is in a position to make a purchase decision. We seed the organization by explaining how we can help companies engage more effectively with their employees. And once we sign up a company, we deploy quickly, with no systems integrators, and customers get value within a month.”

ElNaggar wanted to make sure that employees were doing the right thing for customers. As he said, “We are building a rational business. We don’t want to starve our growth. And we measure employee engagement and productivity. We sign three-year deals with customers, and unlike competitors, we stay with them to make sure they are getting high usage and return on investment from our product. We want to change how people work and make our customers happy enough to be willing to give us references.”

Despite ElNaggar‘s interesting background, he lacked outstanding technical skills or previous success leading startups to profitable exits for investors. For example, he had extensive business development experience and served as a venture capitalist on the boards of several startups, none of which had successful exits. Sapho’s other cofounder, Peter Yaro, started five enterprise infrastructure startups that were acquired by VMware and Sun Microsystems , among others. Marque Teegardin, Sapho’s Chief Revenue Officer since May 2017, previously held senior sales positions in various software companies, including NICE Systems, StoredIQ (acquired in 2013 by IBM), and Mirantis, an open cloud infrastructure provider that had raised $220 million by September 2018.

Case Analysis

Sapho had won “dozens of customers” after four years in business. While it claimed to be growing rapidly, the high growth rate was likely attributable to its low revenues, although in the absence of disclosing revenues, there was no way to know how successful the company was. One possible flaw in Sapho’s strategy was its decision to focus on solving a relatively unimportant problem, the solution to which would not have a dramatic economic benefit for customers. Another challenge was that the previous accomplishments of its top executives were insufficient for Sapho to attract world-class talent.

Principles

- Do

Hire the best cofounders possible to attract the best talent.

Use initial customer traction to raise capital so that the startup can afford to hire more talent.

Promote from within if the candidate can learn to excel in the next job.

- Don’t

Assemble a founding team that lacks the skills needed to be successful.

Fill a position with a mediocre candidate because of pressure to achieve growth goals.

Hold on to initial team members who can’t contribute enough to the company’s future.

Hire an executive who has a strong track record but does not fit with the culture.

Stage 2: Building a Scalable Business Model

Building a scalable business model is a difficult challenge—made even more difficult if the company’s CEO and board are not committed to doing so. As we’ve seen throughout this book, many rapidly-growing companies seek to sustain very high revenue growth and they fear that worrying about how to do so profitably is a distraction. However, if a company can go public while burning through capital, it will eventually have to forge a path to profitability. A handful of charismatic CEOs, such as Tesla’s Elon Musk or Elizabeth Holmes, former CEO of Theranos, can defer that day of reckoning by galvanizing investors’ emotions. However, the better path at this stage is for a company to stop growing quickly until it can make its business model self-sustaining. If that does not happen, the company will have trouble holding on to its talent.

Design an organization with the key functions that must be managed efficiently to build a scalable business model.

Promote or hire executives to lead the functions who fit the culture and have or can learn the skills needed to make their function far more efficient so the startup’s business model is scalable.

Let people go or move aside executives who can’t contribute to this effort or try to slow it down.

Success Case Study: Confluent’s Scalable Business Model Is Built on World Class Talent

Introduction

If the talented inventors of a key product built for a respected company decide to start their own company, good things can happen. The good things are particularly pronounced if the company targets a large market that needs the product they invented. If the company builds a product that delivers better value to customers at a lower price, growth is likely to follow. And that should ease the recruitment of talented executives and others. This comes to mind in considering Palo Alto-based Confluent, a player in the $27 billion market for middleware, software that tracks the flow of data from its source to its destination. Confluent was founded in September 2014 by a team of techies from LinkedIn and by September 2018 had raised nearly $81 million. With over 300 employees (up from three in 2014), Confluent boosted its subscription revenue four-fold in 2017 and said it expected to do the same in 2018, according to my August 2018 interview with CEO Jay Kreps. Kreps was the lead architect for data infrastructure at LinkedIn and developed the open source Apache Kafka distributed streaming platform the business social network used, before cofounding Confluent. He helped develop Kafka to manage the growing complexity of distributed systems brought on by new applications and larger data sets. His unit was spun out and won business from Netflix, Uber, Airbnb, Goldman Sachs, and Target. Audi said that Kafka was powering its connected cars.

Case Scenario

Confluent’s business model was scalable, meaning it grew revenues far faster than its costs so it had a path to profitability. As Kreps said, “We offer a subscription product and as companies get more value, they pay more. This means that we don’t need to grow headcount as fast as we grow revenue. We can’t mess it up. Despite the surplus of private capital, we have to focus on efficiency and make sure that the cost to acquire a customer is less than the amount of recurring revenue that customer generates.” Confluent was organized by function and said it made money on its customers, although it spent money to grow. “We have sales (by region), marketing (public relations, lead generation, advertising, and conferences), customer success (training and service), engineering (architecture and implementation), and product management (developing and tracking the roadmap). Growth requires investment, which is not bad if the core economics are sound,” he said. Confluent tried to promote from within but was doing quite a bit of hiring from the outside. “This organization structure works well. But we often hire functional leaders and executives who have done it before from the outside. We usually know the person we hire and are confident that they can be successful at Confluent. We need people for execution and give them a runway,” said Kreps.

Confluent’s founding team helped it to attract excellent talent. In addition to Kreps, cofounder and Chief Technology Officer Neha Narkhede was one of the initial engineers who created Apache Kafka and was responsible for LinkedIn’s petabyte-scale streams infrastructure. Confluent also hired and promoted Todd Barnett, an experienced sales executive who had previously led the America’s sales force for Acquia, that helped organizations use Drupal (another open source platform) for web engagement management. Barnett joined Confluent as Vice President of Worldwide Sales in April 2016 and in August 2018 was promoted to Chief Revenue Officer. Confluent believed that Barnett would help accelerate its growth when he was hired. According to the company, Barnett had previously worked at “Aperture (acquired by Emerson), Systinet (acquired by Mercury Interactive) and others. With a strong track record for creating momentum-driven sales models that expand both the mid-market and enterprise customer base, Barnett is responsible for expanding the Confluent sales team and driving global sales.”

Case Analysis

Confluent grew much faster than the middleware market while creating a scalable business model by offering a groundbreaking product that was used by LinkedIn. The outstanding technical accomplishments of its founding team made it possible for Confluent to raised considerable capital to fund its rapid growth and to attract outstanding talent such as Barnett, who had previous experience scaling organizations like Confluent.

Less Successful Case Study: BigID Targets a Large Opportunity but Can It Build a Scalable Business Model?

Introduction

When a company says it’s growing at over 100% and won’t disclose its revenues, you can be confident that it’s not quite ready for an IPO. But it’s unusual for me to talk with a CEO who reports 800% revenue growth in a $19 billion market and claims his company is winning business from IBM, Oracle, and a raft of smaller companies like Varonis, Talend, and Symantec.

But that’s what Dimitri Sirota, CEO of Manhattan-based data protection provider BigID, told me in an August 2018 interview. Sirota, who studied physics at McGill and University of British Columbia, was head of strategy for CA Technologies after it acquired cloud security provider Layer7 Technologies, which he cofounded. As he commuted to work from New York City, he was reading and hearing about the abuse of personal information and realized that there was no purpose-built solution for protecting it. This gave him an idea for BigID, “A lightbulb went off in my head: what if you could secure personal information and help companies comply with GDPR and privacy legislation that’s likely to go into effect in Japan, Korea, Australia, Brazil, Chile, and India? There was a gap in the market.”

Case Scenario

Sirota believed that the opportunity for BigID was large and he raised considerable capital to support its growth. As he said, “Access governance is a $1 billion market, data governance is $3 billion, data loss protection is a $1.5 billion market. And the market for data governance is growing at a breakneck pace to $19 billion.” BigID was growing. “Between February 2016 and August 2018, we’ve grown from six people to about 60 and expect to end the year with 80 people and we’ve raised $46.1 million. We were growing so fast that we did Series A and Series B rounds in quick succession. That’s because we were able to get product market fit and repeatedly bring in customers quickly. We are using the money to build a salesforce, putting people in new territories as we generate sizeable revenues from our accounts.” By August 2018, BigID was targeting its next round of financing by growing from about $10 million to $40 million. “We are training people to sell and build a support organization that can provide 24x7 coverage. We are also showing partners interested in the market what we are doing. When we get our Series C, we will go into new territories, expanding into Asia and Europe,” he said.

BigID’s top executive team was missing people with a track record of tremendous success. For example, it lacked a head of sales and was trying to hire one by the end of September 2018. As Sirota said, “We want somebody who has had experience growing from $30 million to $60 million and is a good cultural fit. We should laugh at each other’s jokes. The person should have worked in more places than one and know the challenges and how to solve them.” Nimrod Vax, BigID’s head of R&D, formalized the product development processes as the company grew. According to Sirota, “At the beginning, it’s important to have clarity about what you want to build. You must make sure your minimum viable product solves a problem. After you get product/market fit, you must build a product that can handle commercial realities such as security, scaling, and performance. Then you must support a variety of use cases, introduce quality assurance, and build add-on products.” Prior to BigID, Vax had worked as a development manager at identity management software provider Netegrity , which CA acquired in 2005 for $430 million, and he rose to VP of Product Management before leaving to start BigID. And BigID employed Scott Casey as COO/CFO, yet his previous experience as CFO of previous startups did not include any successful exits and he had not previously served as Chief Operating Officer.

Case Analysis

BigID grew rapidly from a small base as it took advantage of a major push in the spring of 2018 for companies to comply with European privacy regulations. It raised considerable capital, yet it was missing key strengths in its management team and was struggling to hire the talent needed to expand the company, build a scalable business model, and find new markets that would enable it to sustain its growth. It was unclear whether its founding team had the skill to recruit the talent it would need to reach its growth goals.

Principles

- Do

Hire the best functional leaders possible to make key processes such as landing new customers, generating high quality sales leads, and assuring high customer satisfaction more efficient and effective.

Seek candidates for these roles from people in the founders’ professional networks who fit the startup’s culture and have demonstrated their ability to lead a company to an IPO within the startup’s industry.

Once hired, give the executives the freedom to identify and solve business problems.

- Don’t

Hire quickly to fill a key slot without assuring cultural fit and relevant experience.

Attempt to control the key decisions of the newly hired executive.

Stage 3: Sprinting to Liquidity

Sprinting to liquidity works best when the company has made its business processes scalable. If the company has achieved this, it will have hired or promoted key executives into the leadership roles needed to build a scalable business model and sprint to liquidity. Having achieved this goal, the company should be able to raise enough capital to hire sales teams, boost marketing efforts, build or acquire new products, and provide excellent service to bring in new customers at a rapid rate and keep them happy enough for them to boost their spending on the company’s products. If the company has world-class executives, they should be able to attract and promote talented people who can manage the teams of individual contributors in roles such as sales, marketing, product management, engineering, and service who will do the work needed to sprint to liquidity. By setting clear goals and holding everyone accountable for achieving them, such a company should be well positioned to go public.

Success Case Study: With Leadership from Two Nutanix Executives and $296 Million in Capital, ThoughtSpot Sprints to IPO

Introduction

When a startup achieves unicorn status, a private market valuation of at least $1 billion, it marks a considerable leap forward on the path to an initial public offering. The chances for such a liquidity event are increased if the company has excellent top leaders, targets a huge market, is boosting revenues rapidly, and has a scalable business model in place. What’s more, the prospect that such a company could soon go public would ease the recruitment of talented executives who had previously led a private company to an IPO. This comes to mind in considering Palo Alto-based data analysis service provider ThoughtSpot (which raised nearly $296 million in venture capital). ThoughtSpot, which raised $145 million in May 2018 at a pre-money valuation of $855 million, was founded in June 2012 by Ajeet Singh, a Nutanix cofounder. In August 2018, he stepped aside from the CEO position and up to Executive Chairman to bring on Nutanix’s President, Sudheesh Nair, as CEO. ThoughtSpot was growing rapidly. As Nair told me in a September 2018 interview, “We are growing at triple digits [fourth quarter fiscal year 2018 revenues were up 180%, according to Barron’s], winning at the tip of the pyramid, and revenue from our largest customer is eight figures.”

Case Scenario

ThoughtSpot was doing so well because it offered customers what they perceived as a better product in a huge market. By bringing in a new CEO who was well-acquainted with its founder, it was positioning itself well for an IPO. ThoughtSpot viewed an IPO as a funding milestone, a step in its long-term mission. As Nair said, “It’s a tremendous market worth over $100 billion, according to IDC. The value will only increase, and the market will get bigger at a rapid clip. We are solving a difficult problem with the right team. We are investing in a search/artificial intelligence platform. We have three of the five Fortune 5 companies. They choose us due to our platform’s performance, usability, scale, security, and ability to integrate with their systems.” ThoughtSpot was growing—and taking business from publicly traded rival Tableau— because it took advantage of three key trends better than rivals. As Nair said, “First, data is created everywhere at a much more rapid pace from the cloud and IoT—coming from Salesforce, AWS, Azure, and Oracle databases. Second, businesses are in a race with the competition to see who can turn data into actionable insights most quickly. Finally, in looking at one and two, people are the bottleneck; there are not enough database administrators, data analysts, and data scientists to satisfy the demand. A Tableau report takes seven to 10 days to produce. That’s too long. ThoughtSpot shortcuts it all.”

Between Singh and Nair, Nutanix’s pain from losing top talent was ThoughtSpot’s gain. Nair explained that he enjoyed the building stage of a startup when it’s “us against the world.” And he clearly felt he was getting back to that feeling when he joined ThoughtSpot. In September 2018, Singh told me that the combination of his long-standing relationship with Nair from Nutanix and his interest in focusing on product development made him comfortable with the idea of ceding the CEO job and giving Nair the responsibility for achieving ThoughtSpot’s ambitious growth goals. Nair was happy to have someone to talk with about the challenges of being CEO. As he said, “I knew Ajeet and the people he assembled. Being CEO is a lonely job and Ajeet is not pulling out. He will be as involved, and we will work side by side focusing on different decisions.” Nair saw joining ThoughtSpot to change the kinds of conversations he had with customers. As he said, “Nutanix and cloud players were sucking the oxygen out of the industry by cutting prices 40%. I wanted to go from having conversations about saving money to talking about how to help customers make money.” Singh wanted help scale ThoughtSpot after raising the latest round of funding. As he said, “We raised $145 million and I needed help scaling the business. Sudheesh was an angel investor in ThoughtSpot. My passion is product; I was Chief Product Officer at Nutanix. I am like a kid in the candy store and ThoughtSpot was my most ambitious undertaking. I was hoping to have him along for the journey.”

In September 2018, ThoughtSpot had 300 people and wanted to preserve its culture based on the values of selfless excellence, team, and doing the right thing as it grew to 1,000 people. As Singh said, “40% of the team works on product, 40% on sales, and 20% on marketing, general, and administration. We are expanding into Australia, Japan, and Europe and are operating offices in Palo Alto, Seattle, Dallas, and Bangalore.” Filling new roles as the company grew was a challenge. As he explained, “The talent we have developed since the beginning of the company is some of the most valuable. But we need different scaling skills to build new product and business streams. We have a sales person who built a team and became a chief evangelist who landed customers in Japan, Singapore, and Australia.” Before hiring Nair, ThoughtSpot had already succeeded in hiring excellent executive talent. Consider the example of its Chief Revenue Officer, Brian Blond. He joined the company in 2016 having previously led strategic business development and sales, resulting in rapid global growth at enterprise software companies. He had previously been at Vitrue, a social marketing platform provider acquired in 2012 for $300 million by Oracle. Prior to that, he was a sales executive at Moxie Software and BladeLogic, contributing to its 2007 IPO.

Case Analysis

ThoughtSpot reached unicorn status six years after it was founded—and a few months after raising $145 million was able to hire a CEO to supplement the founder’s product development skills. The company’s outstanding executive team was able to develop a product that customers found compelling, which propelled its growth. It seems likely that ThoughtSpot will be successful at continuing to build the company and ultimately go public.

Less Successful Case Study: After Five Years, Exabeam Raises $115 Million to Accelerate Its March to 10% Market Share

Introduction

A company that takes its time to build a scalable business model is better off than one that can’t get more efficient as it expands. If this company is targeting a relatively small market filled with rivals, the challenge is made even greater. For such ventures, the question is whether the company’s cofounders can hire the kind of top-notch talent it will need to sprint to liquidity. Through patience, determination, and disciplined execution, such a company might eventually reach the point where it could go public. By August 2018, these questions loomed large for Exabeam, a San Mateo, California-based security information and event management (SIEM) company founded in 2013. SIEM providers searched through billions of pieces of data in a company’s computer infrastructure to try to figure out which PCs and laptops had been hacked. In an August 2018 interview, Exabeam CEO Nir Polak explained that he saw combat in the Israeli army and served as a top executive at Imperva, a Redwood Shores, California-based $322 million (2017 revenue) cybersecurity firm, and its application delivery platform-subsidiary Incapsula. He came up with the idea for Exabeam because he thought that companies could find the hacker’s path more quickly if an AI-backed algorithm did the searching instead of a person.

Case Scenario

Exabeam had grown rapidly by taking market share from the leading publicly-traded SIEM provider, Splunk. And Exabeam’s success was due to several factors including the perceived value of its product, its ability to raise enough capital, the way it organized its people, and its culture. However, it remained to be seen whether its people could take the company to an IPO.

Exabeam had added staff quickly and organized by function. “We had four people in 2013, we launched in February 2015 and began hiring, Now we have 250. To make sure we are scaling efficiently, we track top line growth and the ratio of cost of goods sold to revenue. We look at how we compare on sales and marketing, general and administrative, and research and development expenses and margins to publicly traded companies when they were at our stage. Every year we need to be much more efficient,” he said. Exabeam had a strong culture and, with its five-star rating on Glassdoor, did not suffer much turnover. “We hire raw talent and let them grow; we have little attrition. I share information from board meetings with everyone. We work together and win together; hold cross-departmental events so people can connect socially; have a no-ego executive staff; engage in open communication. We trust and share, and we do what’s right for the customer.” Exabeam hired people who were seasoned in private and public companies like FireEye and EMC . As Polak explained, “We have heads of marketing, field operations, customer success, engineering, general and administration, and IT who report to me. We are all trying to meet our revenue goals within budget. And we have a strong board with a fiduciary responsibility that will push you.”

Exabeam hired executives with prior experience helping startups to go public. For example, Executive Vice President of Field Operations Ralph Pisani previously led the Imperva worldwide sales organization from an early stage through its successful IPO. Prior to Imperva, he was Vice President of Worldwide OEM Sales at SecureComputing, which was acquired by McAfee. In July 2014, when Exabeam hired Pisani, Polak said, “Ralph brings his vast experience in cybersecurity and sales to play a key role on our team as we continue to grow and develop our technology. [Given the number of competitors in the SIEM market,] having an influential player like Ralph will elevate Exabeam above the noise,” Pisani said he joined Exabeam because of its “impressive founding team that’s applying big data security analytics to arm IT with the tools it needs.” By November 2018, Exabeam had added two more senior executives to its team: Manish Sarin, who since 2012 had been Executive Vice President of Corporate Planning and Development at Proofpoint, as its new CFO and Rajiv Taneja, who had previously been Vice President of Engineering at Cisco, as Executive Vice President of Engineering. As for Exabeam’s future, in August 2018, Polak said, “In three years we will be much bigger, a leader in our industry.”

Case Analysis

Exabeam achieved considerable success, although compared to ThoughtSpot, it had chosen a smaller market opportunity and after almost the same amount of time in business had yet to reach unicorn status as of August 2018. Nevertheless, Exabeam was able to grow rapidly, claimed to be displacing the incumbent in competitive bids, and had attracted a talented executive team from a previous publicly traded company where the CEO and the head of field operations had both worked. It seems that Exabeam will be able to go public by 2021; however, many challenges need to be met to reach that goal.

Principles

- Do

Promote or hire executives to key leadership roles who have previous experience taking companies public.

Let people go or move aside executives who cannot fulfill the responsibilities as the company goes towards an IPO.

Set specific quarterly goals for the company and key functions, reward executives who meet the goals, and hire replacements for those who, after a chance to improve, cannot.

Share information with all employees.

- Don’t

Promote people into executive roles who lack the skill and attitude to fulfill them effectively.

Hire executives from outside who do not fit with the company’s culture.

Hide information from all but favored executives.

Stage 4: Running the Marathon

Success Case Study: SendGrid’s CEO Takes the Company Public in 2017 and Sells Out to Twilio in 2018

Introduction

What happens when you put a talented turnaround executive in charge of a flailing medium-sized, money-losing, stagnant tech company? In the case of Denver-based SendGrid , a firm founded in 2009 that supplied cloud-based email service, you get a publicly traded company that was growing fast and generating positive cash flow and in the 10 months following its IPO had roughly doubled its stock price. SendGrid described itself as a leader in the $11 billion “digital communication” market that provided links to ads, password changes, and other sites at the bottom of emails. In September 2018, SendGrid said it “had 74,000 paying customers, including Spotify, Airbnb, and Uber, and sent 1.5 billion messages on an average day, touching more than three billion unique email recipients every quarter.”

SendGrid’s CEO took on the job in September 2014. According to SendGrid’s 2018 proxy statement, Sameer Dholakia, who had a BA and MA from Stanford and a Harvard MBA, was previously Group Vice President and General Manager of the Cloud Platforms group from 2011 to 2014 and Vice President of Marketing from 2010 to 2011 at Citrix Systems after Citrix’s 2010 acquisition of VMLogix, a provider of virtualization management software, of which he was CEO. These experiences helped prepare him to be CEO of a public company. As he told me in a September 2018 interview, “VMLogix was a pre-revenue, pre-cash flow company when I joined with seven employees. I built it out and in 2008 we had a term sheet to be acquired by Citrix and then the financial crisis hit. We kept the company going and in 2010, Citrix bought the company. I stayed at Citrix and soaked up insights from its CEO about how to manage a company with 5,000 or 6,000 employees.” SendGrid gave Dholakia a chance to go back to being CEO. “I met with a partner at Bessemer Ventures and he told me the SendGrid opportunity was all the things I cared about. SendGrid placed a strong cultural value on humility. It had $30 million in trailing revenue, nearly 200 people, a decelerating growth rate, and a negative 30% margin. I saw the potential for it to be a great company and I joined in 2014,” he said. By October 15, 2018, SendGrid lost its independence after Twilio announced that would acquire the company for $2 billion.

Case Scenario

After its IPO, SendGrid continued to grow quickly and generate positive cash flow although it was unprofitable. In the process of turning around SendGrid, Dholakia replaced most of the executives who were there when he joined, added a new product line, and made the business more focused and productive with a clearly-articulated culture. In the second quarter of 2018, SendGrid, which went public in November 2017, reported faster revenue growth (32%) and $3.9 million worth of free cash flow while reporting a $300,000 net loss. Dholakia, who lived in Silicon Valley, faced a challenge in boosting growth and reducing cash bleed of a company that had most of its people in Denver and in Irvine, California. As he said, “I saw that we could be a leader in push notifications (delivering messages and conversations with end users). We stopped hiring so many people who we couldn’t ingest and make productive. We created alignment around a mission and vision in 2014 and 2015.” SendGrid also launched a second product for marketing, which nearly doubled the company. As he said, “The new product was instrumental; we had a $25 million run rate. And we became laser-focused on improving weaknesses in our product relative to the competition from the perspective of customers. This gave us a tailwind in 2016 and 2017 leading up to our November 2017 IPO.”

Getting the company to IPO-readiness was not without pain. “Getting the right people is a difficult topic. When I stepped in we changed executive leadership. Only one (the general counsel) out of the eight original members of the executive team are still with the company. We had people who were important to getting the company from $0 to $30 million in revenue, but the skill set for a public company is different. If they didn’t have the right skills, we helped them with love and grace in an honest and clear conversation,” he said. For example, in August 2016 Dholakia replaced SendGrid’s head of sales and customers success with Leandra Fishman, who had previously been VP Global Corporate Sales at Jive Software , VP Worldwide Inside Sales at EMC , and VP Sales at VMLogix (where Dholakia had been CEO). Another big change was in culture and organization design. “We have a 4H culture: Happy, Hungry, Humble, Honest. As a public company we have made changes in our go to market, opening new ways to get to customers. We are making long-term investments in product and engineering that will take three to five years to pay off. We are also extending the planning cycle from quarterly before we were public to three to five-year views,” said Dholakia. He was in no hurry to move elsewhere. As he said, “I have so much fun every day. You must love what you’re doing, believe in the mission and vision, and love building the business. We created the category and we are the leader amongst 6 to 12 players (which include AWS’s simple email service). I also love the people and you need a great culture to keep people wanting to be there.” Would Dholakia continue to love the culture after the deal closed in 2019? Twilio said that SendGrid would become a wholly owned subsidiary of Twilio but Dholakia would not be taking over the CEO slot at Twilio.

Case Analysis

SendGrid faced an existential crisis when it brought in Dholakia as CEO in 2014. He took the company public about three years later and by September 2018 had overseen rapid growth, positive cash flow generation, and a more than doubling of its stock price. A key part of that success was its ability to broaden its product line, expand its geographic scope, and replace almost every member of its executive team with skilled outsiders. As of September 2018, Dholakia appeared to be enthusiastic about the company, his job, and the people he worked with. However, the next month SendGrid was acquired. I’d give Dholakia high marks for turning around the company when he joined and finding a good exit for the company.

Less Successful Case Study: Anaplan Files for IPO with Inexperienced Executive Team

Introduction

Companies can go public despite imperfections. For example, as we saw in Chapter 3, planning software provider Anaplan had raised substantial amounts of capital with help from a new CEO who had brought in many new executives. And in September 2018, Anaplan filed for an initial public offering despite losing substantial amounts of money and fielding a team of executives with little experience working together, including a then-recently departed accounting officer who the week before had quit Tesla after working there for less than a month.

Anaplan, which was founded in 2006 and valued at $1.4 billion in November 2017, had undergone considerable turmoil at the top. Anaplan’s CEO since January 2017, Frank Calderoni spent 17 years as CFO, often paired with an operating role, at Cisco Systems and SanDisk . Most recently, he had been CFO and EVP of operations at Red Hat, an enterprise software company, where he spent less than two years. Calderoni took over after its previous CEO, Frederic Laluyaux, who had previously been an executive at SAP, parted ways with the company in April 2016. Laluyaux spent over three years as CEO, having taken over in September 2012 from cofounder Guy Haddleton. Laluyaux raised $90 million in a Series E round of capital in January 2016, which valued Anaplan at $1.1 billion. But the board decided that the company would not be able to go public under Laluyaux’s leadership. After Laluyaux left, then-Anaplan Chair Bob Calderoni (Frank’s brother) said, “The board and Fred believe it’s the right time to bring in a new set of talent to take us to a much higher level and become a much bigger company.” Ravi Mohan, Anaplan board member and managing director at Shasta Ventures, said, “Unbridled growth [is no longer] the most valued characteristic. Now, it’s profitable sustained growth, and we’re building a company that reflects that.” When he took over as CEO, Anaplan, which makes money by selling monthly subscriptions, was large enough to go public and was still growing fast. As Calderoni pointed out, “In its fiscal year ending January 2017, Anaplan had $120 million in revenue, was growing at 75%, added 250 customers for a total of 700, employed over 700 people in 16 offices in 12 countries, had raised a total of $240 million in capital, and generated good cash flow.”

Case Scenario

In September 2018, Anaplan filed for an IPO. It reported 40% revenue growth along with considerable losses and a management team with very limited experience working together. Anaplan’s prospectus indicated that its revenues had risen about 40% to $168 million in fiscal 2018, its user count had soared 126% from 434 in January 2016 to 979 in July 2018, and its net loss increased 19% to $47.5 million in 2018. Along with the losses came a management team with strong prior experience, little of which occurred at Anaplan. For example, its CFO, David Morton, was hired in early September 2018 after he had toiled for less than a month as Tesla’s Chief Accounting Officer. From 2015 to August 2018, Morton had been Seagate Technology’s CFO. Anaplan’s Chief Revenue Officer, Steven Birdsall, had been onboard since February 2018; previously he held brief executive positions at Radial, an e-commerce startup, and Hearst Business Media. Prior to that Birdsall was a top executive at SAP, including Chief Operating Officer. What’s more, Anaplan’s Chief People Officer, Chief Marketing Officer, and Chief Account Officer had also joined within the year before its IPO filing. As Anaplan’s prospectus warned, “These members of management are critical to our vision, strategic direction, culture, and overall business success. Because of these recent changes, our senior management team, including members of our financial and accounting staff, has not worked at the company for an extended period and may not be able to work together effectively to execute our business objectives,” As we saw in Chapter 3, by November 2, 2018, it was clear that Anaplan’s IPO had been successful, valuing the company at $4 billion—way above its $1.4 billion valuation in its last pre-IPO financing round.

Case Analysis

Anaplan endured considerable turmoil at the top but its most recent CEO was able to file for an IPO in September 2018. While one of Anaplan’s lead investors was eager for the company to grow profitably when the board appointed Calderoni as CEO in January 2017, its financial filings presented a mixed picture: rapid growth with growing losses. Moreover, Calderoni scrambled to appoint executives responsible for revenue, marketing, people, and finances after his appointment. In so doing, he assembled a team of people with strong prior work experience who had not worked together effectively. By November 2018, it was unclear whether its executive team would be able to lead Anaplan to profitable growth after its successful IPO.

Principles

- Do

Articulate the company’s vision and values clearly and embed them in the process for hiring and promoting people.

Hire a top executive team that is motivated by the company’s vision, shares its values, and has prior experience running key functions in a rapidly growing public company.

Replace top executives who are unable to achieve the company’s short- and longer-term goals.

- Don’t

Neglect the formulation and communication of vision and values.

Hire executives with strong functional expertise but limited experience in the industry and unclear commitment to the company’s vision and values.

Hiring, Promoting, and Firing Success And Failure Principles

Summary of principals for hiring, promoting, and letting people go

Scaling Stage | Dos | Don’ts |

|---|---|---|

1: Winning the first customer | Hire the best cofounders possible to attract the best talent. Use initial customer traction to raise capital so that the startup can afford to hire more talent. Promote from within if the candidate can learn to excel in the next job. | Assemble a founding team that lacks the skills needed to be successful. Fill a position with a mediocre candidate because of pressure to achieve growth goals. Hold on to initial team members who can’t contribute enough to the company’s future. Hire an executive who has a strong track record but does not fit with the culture. |

2: Scaling the business model | Hire the best functional leaders possible to make key processes, such as landing new customers, generating high quality sales leads, and assuring high customer satisfaction, more efficient and effective. Seek candidates for these roles from people in the founders’ professional networks who fit the startup’s culture and have demonstrated their ability to lead a company to an IPO within the startup’s industry. Once hired, give the executives the freedom to identify and solve business problems. | Hire quickly to fill a key slot without assuring cultural fit and relevant experience. Attempt to control the key decisions of the newly hired executive. |

3: Sprinting to liquidity | Promote or hire executives to key leadership roles who have previous experience taking companies public. Let people go or move aside executives who cannot fulfill the responsibilities as the company goes towards an IPO. Set specific quarterly goals for the company and key functions, reward executives who meet the goals, and hire replacements for those who, after a chance to improve, cannot. Share information with all employees. | Promote people into executive roles who lack the skill and attitude to fulfill them effectively. Hire executives from outside who do not fit with the company’s culture. Hide information from all but favored executives. |

4: Running the marathon | Articulate the company’s vision and values clearly and embed them in the process for hiring and promoting people. Hire and motivate a top executive team that is motivated by the company’s vision, shares its values, and has prior experience running key functions in a rapidly-growing public company. Replace top executives who are unable to achieve the company’s short- and longer-term goals. | Neglect the formulation and communication of vision and values. Hire executives with strong functional expertise but limited experience in the industry and unclear commitment to the company’s vision and values. |

Are You Doing Enough to Hire, Promote, and Let People Go Effectively?

Have you articulated a clear vision and values that inform the process of hiring, promoting, and letting people go?

Are you weighing the advantages and disadvantages of promoting from within to fill a new executive or management role?

If a strong contributor does not fit the requirements of a new role, do you help the person find a new job or manage them respectfully out of the company?

If you hire from the outside for a new role, do you evaluate whether the candidate embraces the company’s vision and values, has the skills needed to do the job as it evolves, and will take responsibility for achieving the company’s goals?

Conclusion

Hiring, promoting, and letting people go effectively is an element in a cluster of scaling levers that enable a company to implement its growth strategy for turning an idea into a large company. Underlying the process of hiring, promoting, and letting people go effectively is the notion that a leader must be hard-headed and warm-hearted when it comes to deciding which person should perform a key role in the organization as it progresses from winning its first customers to running the marathon. The right person for each role should embrace the company’s vision and values and can meet the goals the company expects of the role as it changes to help the company sustain its growth. Chapter 7 will focus on how companies hold people accountable for achieving the company’s short- and longer-term goals.