The mission and strategy layer, which consists of three scaling levers that relate to defining the company’s purpose and formulating and raising capital for its growth strategy.

The execution layer, to be examined more closely in Chapter 5, in which leaders implement the strategy by managing four scaling levers: redefining jobs; hiring, firing, and letting people go; holding people accountable; and coordinating processes.

The mission and strategy layer

Creating growth trajectories: As we’ll see below, growth trajectories articulate a startup’s current and potential sources of revenue growth by making clear choices about the markets in which the startup will compete and how it will gain share.

Raising capital: As a startup scales, founders must persuade different kinds of investors to provide capital. Those investors will invest, in part, depending on their confidence in the startup’s growth trajectories.

Sustaining culture: By defining the startup’s values, the founder articulates the startup’s enduring purpose, which helps motivate potential and current employees and helps to attract the right kinds of investors.

Growth Trajectories

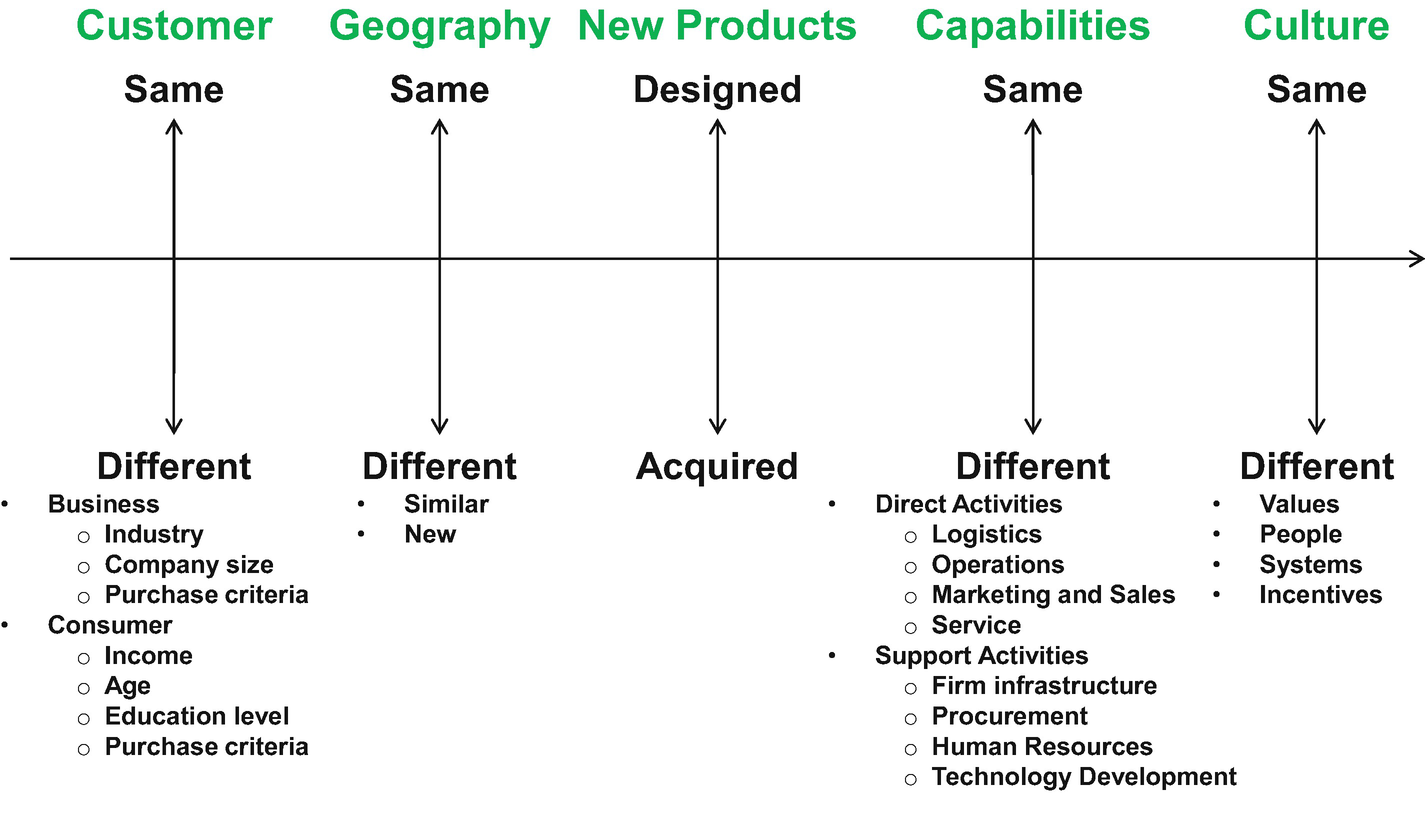

Five dimensions of growth

Customer groups: Customers are grouped differently depending on whether they are businesses or individuals. Businesses are grouped based on attributes such as industry, size, purchase criteria, or level of interest in buying a company’s product. Consumers can be grouped based on age, income, and the other factors illustrated.

Geographies: This refers to the regions in which the company sells its products.

Products must be renewed or expanded because of customer needs and technology changes and competitors adapting their strategies in order to take share from a company’s successful product. Products can be built internally or acquired,

Capabilities are a company’s business functions, such as product development, sales, and customer service.

Culture means the company’s values and the specific practices used to hire, promote, and motivate people so everyone will act according to the values. Capabilities and culture can be both a source of growth and a means of achieving growth.

How can growth levers be pulled to gain market share? To gain market share, startups must convince customers to buy. And to do that, the company must outperform rivals on the customer’s ranked purchase criteria (CPC), factors such as quality, price, and product variety, and deploy capabilities, such as product development, sales, and customer service, that enable the startup to win on those CPC consistently.

Customer perception of Berlin Packaging on ranked purchase criteria

Purchase Criteria | Berlin Relative Performance | Basis for Assessment |

|---|---|---|

Price | Matching | Berlin seeks to match the price customers require, as do its rivals. |

Reliability of supply | Superior | As of April 2015, “for the last 131 months in a row we have delivered 17,000 shipments a month 99% on time; that is better than the industry,” according to Berlin. |

Product quality | Superior | Products conform to customers’ quality standards more frequently than rivals, says Berlin. |

Increase customer EBITDA | Superior | Berlin gives customers services that boost their EBITDA in exchange for long-term contracts. |

Berlin Packaging’s relative performance on critical plastic bottle capabilities and importance to winning in customer purchase criteria

Capability | Evaluation Criteria | Assessment and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

Purchasing | Importance to purchase criteria | Economies of scale in purchasing helps Berlin to lower its costs, thus enabling it to match price demands. |

Berlin relative performance | Superior. Berlin designs its own packaging and contracts out the manufacturing to 700 suppliers around the world. | |

Outbound logistics | Importance to purchase criteria | Efficient outbound logistics helps Berlin to maintain high shipping reliability. |

Berlin relative performance | Superior. Berlin uses tight control of outbound logistics to ship the right packages to the right destinations on time. | |

Human resources management | Importance to purchase criteria | Human resources management enables Berlin to attract and motivate people who boost Berlin’s EBITDA. |

Berlin relative performance | Superior. Berlin uses a psychological contract with its employees, paying them more than the industry standard to boost Berlin’s EBITDA. | |

Firm infrastructure | Importance to purchase criteria | Firm infrastructure is applied to customers to boost their EBITDA. |

Berlin relative performance | Superior. Berlin gives away services to customers in exchange for long-term contracts. It lends customers money to buy productivity-enhancing machines at zero interest, helps customers to install enterprise resource planning and lean manufacturing techniques, works with them to get International Standards Organization-quality certified, and helps customers to analyze weaknesses in their competitors’ product lines and develop products to exploit those weaknesses. |

Home AED growth trajectory

Dimension | Choice |

|---|---|

Target customer | SCA candidates living in U.S. apartments |

Winning on CPC | High quality product sold at lowest price in the industry ($500) |

Manufacturing | Outsource to China |

Distribution | Express mail from warehouse |

Marketing | Internet and radio advertising |

Sales | Call on cardiac care centers |

Takeaways for Stakeholders

- Startup CEO

Solve an important problem of potential customers in a unique way.

Interview potential customers to understand the factors that drive their purchase decisions.

Build inexpensive prototypes, get feedback from earliest customers, and improve the prototype until customers are willing to buy.

Keep looking for new customer groups who will buy the product.

Adjust marketing, sales, and service processes to create high customer retention and repurchase.

- Customers

Consider working as a design partner with a startup that aspires to solve your most painful problems.

If you are highly satisfied with the startup’s product and support, consider recommending the startup’s product to others in your professional network.

- Investors

Seek out startups that fit with your firm’s skills and provide them capital and advice that helps them build sustainable growth trajectories.

Growth Trajectories Success and Failure Case Studies

In this section, I offer case studies of growth trajectories used by successful and less successful startups at each scaling stage, analyze the cases, and extract principles for helping founders to create sustainable growth trajectories at each stage.

Stage I: Winning the First Customers

Pick the right pain point. Identify unmet customer needs that are important to potential customers, ideally based on the CEO’s own experience and skill.

Find design partners. Find two or three potential customers who are so eager for a solution to this pain point that they are willing to collaborate with the startup to help develop the product.

Build and get feedback on prototypes. The startup should develop an inexpensive version of its product with the features that are most important to these design partners. The startup should observe how the design partners use the prototype, get feedback on what works, what is missing, and what needs to be fixed, and then repeat the process until the customer is eager to purchase the product.

Develop a sales strategy. Once the startup gets its first customer, it should identify a group of customers that is most likely to want to purchase the product and create a process that will introduce the product to an enterprise or consumer, encourage the right people to try it, and ultimately pay for the product.

Successful Case Study: Platform.sh Wins Its First Customers After Careful Development and Extends Its Lead

Introduction

Platform.sh, a San Francisco-based application platform as a service supplier, was very successful at winning its first customers and expanding from there. Founded in 2010, Platform.sh described itself as “an automated, continuous-deployment, high-availability cloud hosting solution that helps web applications scale effortlessly and serve the most demanding traffic. Developers can develop, test, deploy, and maintain their applications faster and more consistently.” Before joining Platform.sh, as CEO in July 2014, Fred Plais founded or co-founded three other businesses (Commerce Guys, the software vendor behind Drupal Commerce; af83, a digital agency operating in Paris and San Francisco; and Infoclic, a natural language search engine in 2000).

Case Scenario

To win initial customers, startups must identify customer pain and develop a product that relieves that pain. Platform.sh clearly passed this initial stage of the scaling process. By June 2018 it had 650 customers including GAP, the Financial Times, Stanford University, and Adobe Systems. Platform.sh spent years fitting its product to what it saw as a big unmet need. As Plais said, “We launched Platform.sh in 2014 after taking three years to build it. We saw that companies were experiencing two problems: they needed to develop and deploy business-critical web applications in response to rapid changes in the marketplace and they had to make the transition from developing to deploying these applications without crashing their production sites.” Platform.sh’s initial customers were developers who worked for retail companies. As Plais explained, “We got really good traction by selling to developers who were making the transition from building applications on laptops to the cloud. We went from retailers to media, including the Financial Times, Slate, Le Temps, and Hachette as well as social networks. Our business model was to offer a free trial for a month followed by two paying options: the developer and enterprise offerings.”

There was more to winning the first customers than simply building a product that customers loved. If the startup’s product was made for business customers, the startup needed a carefully considered and well-executed sales process to win those initial customers. Platform.sh did so through a marketing strategy that built on strong relationships with developers. “We have won customers because we focus our marketing on how well our service solves their pain points. While developers lack the budgets for our product, they work through the layers of the organization to convince those who do have budgets, such as the vice presidents of engineering or chief technology officers, to buy our product,” said Plais.

Case Analysis

Focus on an important source of customer pain. Platform.sh picked the right problem: the expanding need for companies to develop new business applications without interrupting their existing operations.

Invest heavily in a product that relieves that pain effectively. What’s more, Platform.sh took three years to develop a solution to this problem that worked well for retail customers who were feeling this pain most acutely.

Develop and execute an efficient sales strategy. Finally, Platform.sh was able to persuade companies to pay for its product by giving it away to developers who quickly recognized the product’s value and acted as internal ambassadors for introducing the company to the higher-level executives who controlled budgets for its product.

Less Successful Case Study: harmon.ie Takes Its Time Winning Customers

Introduction

harmon.ie, a Boston-based software maker that organized corporate data by topic to make workers more productive, was founded in 2008. harmon.ie described its product as “a suite of user experience products that empower the digital workplace.” A global company serving thousands of enterprise customers, harmon.ie helped information workers focus on getting work done, rather than on using a multitude of tools. harmon.ie helped Microsoft customers to “increase their adoption and return on investments in SharePoint, Office 365 and other Microsoft collaboration products.” harmon.ie CEO Yaacov Cohen was a Paris native who graduated with a degree in computer engineering from Haifa, Israel’s Technion. In 1994, he joined Mainsoft, a Tel Aviv-based maker of application porting software, where he eventually rose to CEO, after relocating the company to San Francisco in 2000. In June 2008, he relaunched Mainsoft in Boston as harmon.ie, offering “an enterprise collaboration and digital workplace company. He brought in new venture capital, a new management team, and a new product line to humanize the digital experience by aggregating multiple cloud services into business users’ comfort zone: the email client.”

Case Scenario

harmon.ie won customers, but after Cohen’s 24 years of involvement with the company (including his time at Mainsoft), took its time scaling the company. As Cohen explained, “We started harmon.ie in 2008 with the idea of making enterprise software as easy to use as consumer applications. From no revenue in 2008, we reached $10 million in annual recurring revenue in 2017. We have self-funded since 2009.” Cohen rejected both the Silicon Valley and Israeli models of entrepreneurship. As he said, “We loved the energy and passion for changing the world in Silicon Valley and saw that the goal of Israeli companies was to get acquired by a big U.S. company. They looked at people as pairs of eyeballs, They don’t respect my soul.” harmon.ie sees itself as more humanistic. “Social networks are destructive, competing for attention. I believe in focus and mindfulness, committing to something bigger than you. It is impossible for you to concentrate when your iPhone is constantly interrupting you. To make it easier for you to concentrate, harmon.ie organized information by the most important topics to each of its users, the five things you care most about, rather than by app,” said Cohen.

harmon.ie depended heavily on Cohen’s personal salesmanship to develop its customer base and found its first customers in government. “Our first customer was the Missouri Department of Transportation. I spent lots of time flying from customer to customer. I met with the chief information officer of Missouri and offered advice on whether Missouri should trust Gartner’s roadmap for Microsoft. The CIO said, ‘I feel I should do business with you and I think you care about money.’ Missouri bought $260,000 worth of software from us.”

Case Analysis

Offer customers a vitamin, rather than a drug. In the context of winning customers, a vitamin is a product that sounds like it should be useful but is not a drug (a must-have cure for urgent pain). harmon.ie’s idea of organizing information by topic struck me as a vitamin rather than a drug. Since the company won customers, some organizations found it worth buying. Yet the very slow pace of harmon.ie’s scaling hinted that its product was not a drug. In short, harmon.ie seems to have picked the wrong problem.

Put the CEO on the road making all key sales calls. Depending too heavily on the CEO to bring in all new customers impedes a company’s growth. Indeed, as Cohen said, he spent 20 years flying from Tel Aviv to the U.S. twice a month. To his credit, Cohen recognized the need to hire sales people and give them more of the responsibility for bringing in customers. However, harmon.ie’s slow pace of building and training a sales force (Cohen hired actors to play customers in Tel Aviv as part of the company’s sales training) suggests that the company would not become more efficient as it grew.

Principles

- Do

Focus product development on relieving intense customer pain.

Collaborate with early customers you already know to develop and deliver a better product that relieves customer pain.

Sell to a customer group that feels this pain more intensely than others.

Use a sales strategy that has the potential to scale efficiently.

- Don’t

Build the initial product around a “vitamin.”

Cold call potential customers before doing research to identify groups who will need the product the most.

Sell the product through a long, CEO-led consultative process.

Stage 2: Building a Scalable Business Model

Target customers. Choose which customers to target as the firm grows based on a combination of growth vectors such as customer group or geography. Typically, startups focus on a single customer group in Stage 1 and either add new customer groups or expand geographically within the same customer group(s).

Product line. Develop the product that the company will sell initially and identify adjacent ones, such as complementary products that are natural extensions of the initial product.

Successful Case Study: Threat Stack Grows Rapidly and Plans to Follow the Same Six-Vector Growth Trajectory as Industrial Defender

Introduction

Boston-based Threat Stack was a cloud security service provider whose CEO previously founded Industrial Defender, a cybersecurity firm that protects industrial control systems for the electrical grid and oil, gas, and chemical companies, which Lockheed Martin acquired in 2014. The CEO of both companies, Brian Ahern, earned an electrical engineering degree from University of Vermont and started Industrial Defender in 20012 with help from an unnamed angel investor who “bet on people heading in the right direction.” Ahern oversaw rapid growth at Threat Stack. He took over as CEO of Threat Stack in May 2015 and it grew from 11 employees to about 100 in September 2017, and he expected to add 86 more in 2018. Between 2016 and 2017, its annual recurring revenue was up 187% and in the 12 months ending March 2018 that growth rate accelerated to 342%.

Case Scenario

Ahern proposed his own model, breaking down the challenge of scaling into three stages based on funding levels: Early (during which a company raises seed, Series A, and B funding), Growth (Series C and D), and Later (Series E to IPO). Ahearn expected to follow the same approach with Threat Stack as he did with Industrial Defender, whose growth trajectory evolved along six vectors. Specifically, as it grew, Industrial Defender shifted from selling its initial built product targeted at an initial customer group; expanding to new customer groups and then to new geographies; and finally to unserved customers in those groups through channels and partners.

Threat Stack intended to follow a similar path. As Ahern explained, “Initially, we built a great product that we are selling to middle market customers; next, we are expanding from the middle market to Fortune 500 customers. We will then invest in leveraging partnerships and channels to expand our reach within served markets; followed by an investment in geographic expansion from North America to Europe and eventually Asia Pacific. And finally we will transcend our served markets from the commercial sector to the government sector. In March 2018, we were in the first phases of our build strategy, continuing to build a great product selling to mid-market.” However, Ahern’s geographic expansion strategy cost jobs for some Threat Stack employees. In October 2018, Threat Stack announced that “in support of its refined strategy, we have made a strategic decision to reallocate resources” which would cost the jobs of “less than 10% of [its 150 as of May 2018] employees. Threat Stack said it planned to fill 17 open positions, which would leave its headcount unchanged.

Case Analysis

Industrial Defender achieved some success with its growth trajectory, although it was acquired for an undisclosed amount after 12 years, so it is difficult to evaluate how successful. To be fair, Threat Stack was growing rapidly, albeit from an unknown base of revenue. It is also likely that Ahern gained considerable insights into building sustainable growth trajectories from his Industrial Defender experience and was likely to apply them to Threat Stack. One key principle that emerges from these cases is that in the first stage of scaling a startup should seek to win customers within an initial market segment and in the second stage it should expand into a different group of customers. Ahern wanted next to target larger companies and ultimately tried to mop up the remaining customers in those segments through channel partnerships. In the third stage of scaling, Ahern believed in geographic expansion within many of the same customer groups. To that end, Threat Stack wanted to replace employees who did not fit its strategy with those who could help implement it.

Less Successful Case Study: Actifio Struggles to Shift into a New Customer Segment

Introduction

Waltham, Mass.-based Actifio, founded in July 2009, provided company data storage as a service. According to Actifio, its service “replaces siloed data management applications with a radically simple, application-centric, service-level-agreement-driven approach that lets customers capture data from production applications, manage it more economically, and use it when and where they need. The result is enterprise data available for any use, anytime, anywhere, for less.”

In October 2012, my interview with Actifio’s founder and CEO, Ash Ashutosh, reflected optimism for an initial public offering by the end of 2013. Ashutosh was an expert in storage; before he started Actifio, he was Vice President and Chief Technologist for Hewlett Packard’s storage business and was a partner at Greylock Partners. But he left there in 2008 and decided to open Actifio soon thereafter with the idea of making “copy data management (CDM) radically more efficient.”

What is CDM? Companies make many copies of the same electronic data to analyze and share it and also to protect themselves if their computing infrastructure crashes due to a blackout or to comply with record retention policies. These copies are produced by different people in different departments. In the past, these copies were stored in different ways, including magnetic tapes, hard disks, and even on paper hived away in boxes. Storing so many different copies of the same data was inefficient. Ashutosh saw clearly that several recent trends could make it possible for companies to obtain the perceived benefits of all those copies at a much lower cost. For example, the growing popularity of virtualization, a way to store and retrieve data with less hardware, coupled with the rising share of hard disk as the primary medium for data storage meant that CDM could get much more efficient. And that meant that companies could have only one copy of their “production data” instead of “between 13 and 120.” And companies could “reuse that golden copy multiple times for multiple applications.” Fixing CDM was a $34 billion opportunity in Ashutosh’s estimation, one that no other companies were addressing.

Ashutosh started Actifio in July 2009. Between the April 2010 introduction of its Protection and Availability Storage (PAS) product, an “appliance” consisting of a cluster of servers and software that cost companies anywhere from $50,000 and $1.2 million depending on their data volumes, and October 2012, Actifio grew at “500% year-over-year, faster than any enterprise storage company ever.” Starting with four people, it had won 170 customers by October 2012. Behind that growth was a boost in efficiency that Actifio customers got when they installed its product. According to Ashutosh, Actifio’s product could cut by 95% the “data footprint” that companies created in their CDM process while reducing by 75% the amount of “network bandwidth” required to move it around their data centers.

That October, Ashutosh painted a bright picture of Actifio’s future. It planned to add 80 people in 2013 as it expanded globally, hiring sales and marketing people and product developers. He expected Actifio to grow from 200 to 800 customers by the end of 2013 and was targeting the end of 2013 or early 2014 for an initial public offering. But managing a rapidly growing company loomed as a challenge. As Ashutosh explained, “2012 is our break point.” By that, he meant that the company was “going from startup to grown up.” And that meant he was talking to his employees about how important it was “to consolidate our focus on quality when we release, sell, and service our products.” He expected that another such break point would occur after Actifio’s IPO. By then, it would have revenues “between $100 million and $150 million and will control 10% of the market.”

Case Scenario

Six years after that bullish projection, Actifio was still private and had not raised new capital since March 2014 when a $100 million round of funding valued the company at $1.1 billion. At the core of this stall out was a failure to build a sustainable growth trajectory when it shifted its focus onto a new customer group from large companies to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In February 2015, Actifio had been growing for years by selling its product to very large companies. But as Ashutosh told me then, he was thinking about finding a way to add more predictable cash flows to Actifio’s income statement. To that end, the company created a service called Actifio One, a “business resiliency cloud” that would deliver the company’s technology to SMEs via the cloud using a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) model that would yield monthly cash flows for Actifio and would be sold and serviced to SMEs through distribution partners.

He envisioned that ActifioOne would be targeting a huge market opportunity worth $580 billion, which was the amount Ashutosh said SMEs spent on IT. As he explained in a July 2016 interview, he thought that it would be much more efficient to sell to distribution partners who sold to SMEs. “With big companies, it takes us 83 days to convince them that we can generate business value. But it can take six to 14 months for their procurement departments to qualify us and pay us as a first-time supplier. Working with distribution partners who sell to SMEs, the procurement process is shorter: 20 to 80 days.”

Sadly for Actifio, it took about six months for the company to realize that this strategy would not work. As Ashutosh said, “We spun out a separate group across the street. After one-and-a-half quarters we realized that the logic was right but the reality was that we had the organizational DNA of working closely with large enterprises, developing technology solutions to work with petabytes of data.” Actifio then realized that it lacked the capabilities to sell successfully to SMEs. “One of the biggest differences in working with SMEs was how we needed to run finance. Whereas big companies might make three to five big payments during a contract, SMEs would pay monthly. To bill and collect from them we needed to add 20 people and be (Payment Card Industry) PCI-compliant so we could accept credit cards from them. Also, we were uncomfortable not having a direct relationship with the end users of our product,” he said. Actifio decided to scrap its separate subsidiary and instead license its technology to bigger “service providers,” companies that deliver an array of IT services to SMEs. As Ashutosh explained, “We license our technology to 5 of the 10 largest service providers that deal with SMEs. Like large organizations, they make a smaller number of large payments. And they may have 100 to 600 SME customers within a region. To sell to them, we need to show that our technology will help their SME customers to cut capital expenditures and achieve operational excellence.”

A year later, Actifio was cutting back to achieve profitability and an IPO was off the table.

In July 2017, he said that an IPO was not a current possibility and that Actifio was “on track for its third consecutive profitable quarter, although it went into the black partly because of staff reductions.” As he said, around the end of 2016, “we started hearing from our customers. They told us, ‘Hey guys, we want to choose you as a strategic platform, but you better be able to survive long term.’ That meant we either had to be profitable or we had to go public. Getting to profitability became our imperative. We did what was required. We got out of geographic markets where we only had a few customers. We got out of other vertical industries that didn’t really help us create a scalable business. Yes, we reduced the number of people, but we also have hired new people for different geographies and different verticals. We brought in 87 new people last year [who] had different skill sets. We brought in people with cloud capabilities that we didn’t have 18 months ago. Our head count was about 360 then. We are at 346 now.”

Nevertheless, Actifio had thousands of customers and was growing in two market segments: DevOps and the hybrid cloud. As Ashutosh said, “We have more than 2,200 customers and add an average of about 100 new customers every quarter. Most of our customer base is within large enterprises that spend on average between $200,000 and several million dollars with us per transaction. We just closed deals with one of the largest retail organizations, one of the largest organizations in healthcare [and] pharma, and with the fifth-largest bank. In all cases, they were saying, ‘Hey, I have thousands of developers and I can’t afford to have them twiddling their thumbs while they wait for data.’ Hybrid cloud storage is one of the fastest-growing [trends] with many of our large customers. Hybrid cloud is about 6% of our business now. It was zero three quarters ago.”

Ashutosh’s persistence paid off in 2018. That August, Actifio raised another $100 million, valuing the company at $1.3 billion. Ashutosh said that its customer base topped 3,000 including five of top 20 global financials, four of the top 10 energy companies, three of the top 10 healthcare providers, six of the top 10 service providers, and four of the top 20 global retail organizations. By November 2018, it remained unclear whether Ashutosh, who said Actifio had become a multi-cloud data-as-a-service company targeting a $50 billion market, could use its latest investment to go public or be acquired.

Case Analysis

Don’t confuse a market’s size with its profit potential. When Actifio targeted SMEs, Ashutosh estimated that there was a $680 billion market opportunity. That figure seemed to me to be much higher than the addressable market for Actifio’s services but given that SMEs have smaller IT budgets it seemed that pricing would be lower than for large companies. The lesson here is to do detailed market research before launching a new growth vector to gain deeper insight into the market’s profit potential.

Don’t assume you will gain market share unless you have a competitive advantage. As I discussed at the beginning of this chapter, to gain market share, a company must deliver superior performance on CPC and deploy capabilities in a way that enables it to outperform its rivals. Ashutosh discovered soon after launching its SME strategy that Actifio could not outperform its rivals in working with channel partners because its culture was based on close collaboration with customers, a collaboration that was impossible to achieve when selling through channels that maintain those relationships. If Actifio had done the right research, it would have known this before launching the strategy.

Don’t pursue new growth opportunities unless you can scale. Many companies go public with rapid revenue growth and significant net losses. This gives some CEOs the hope that they can do the same thing. Yet the experience of Actifio and many other companies that sell to businesses is that lengthy sales cycles and winning by offering customers the lowest price is not scalable. As I discussed in Chapter 1, startups should not “pour gasoline” on their business until they can get more efficient at selling as they grow. Actifio does not appear to have figured out how to do this. After four years of struggle, perhaps Actifio’s August 2018 capital infusion was a sign that its business model had finally become scalable.

Principles

- Do

Target new growth vectors with significant profit potential.

Research whether the startup’s product can outperform rivals on the new growth vector’s CPC.

Win market share by applying capabilities at which the startup excels.

Market, sell, and service customers in the new growth vector in ways that lower the cost of those activities as the startup scales.

- Don’t

Assume that a large market opportunity means big potential profits for the startup.

Assume that the startup’s ability to win market share in its core market will lead to similar gains in the new market.

Grow in existing markets through higher marketing, sales, and service costs and lower prices.

Stage 3: Sprinting to Liquidity

Target customers: Often startups that are sprinting to liquidity seek to do so by selling to the same customers as they have in the past, but to find those customers in new geographies. For example, startups seeking to go from $25 million to $100 million in revenue might attempt to do so by entering, say, 50 countries where it currently does not operate.

Product line: The injection of capital that often kicks off this stage of growth can be used to adapt a startup’s core product to the specific requirements of customers in new geographies and to add to the company’s product line, often through acquisitions of companies that have built products that the company can sell to its current and potential customers.

Partnerships: The third scale of staging often demands that CEOs form partnerships with companies in the new countries in which the startup hopes to expand. The terms of such partnerships could require investment in the partner, sharing in marketing and service costs, and splitting revenue generated through the partnership.

Success Case Study: Looker Sprints to a 2019 IPO

Introduction

In October 2017, Looker, a Santa Cruz, California-based supplier of analytics tools for businesses such as business intelligence (BI) and data visualization was planning a 2019 IPO. According to Gartner, the $18 billion market for data analytics was expected to grow at a 7.6% compound annual rate to about $22.8 billion by the end of 2020. Looker’s CEO, Frank Bien, who joined the company as president in 2013, grew up in a family of technology entrepreneurs and did not want to follow in their footsteps. But apparently, he could not resist. He ended up helping three startups get to the point where they were acquired by other companies. Bien was “a punk rock kid in LA in the 80s and never had a master plan for running a company.” But he was an executive at four startups that grew and were later acquired: Vignette bought Instraspect Software for $20 million in 2003, KEYW bought SenSage in 2008 for about $35 million; EMC acquired Greenplum in 2011; and VMWare bought Virsto in 2013.

Case Scenario

Looker had grown rapidly under Bien’s leadership. As Bien said in a May 2018 interview, “In the last 22 quarters we’ve grown from under 20 employees to about 500 and from a few customers to 1,500 including Amazon’s Retail Group, Fox Networks Group, Square, trivago, CrossFit, and Five Guys.” Looker had raised $180 million in funding, was growing revenue at 85% a year, and had boosted the size of its average contract by 75% since 2015. While Looker’s vision had not changed, its customers did. “Technology companies were our first customers: people out of investment banks and Google want the most sophisticated tools. The next group of customers was Facebook users. After that our product was adopted by Fortune 200 companies like Cigna and State Street. 20% of our customers are in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa doing GDPR stuff [General Data Protection Regulation, meaning the right to be forgotten]. We built our growth trajectory around our financial model. There are between 100,000 and 500,000 potential customers in the world and if our customer acquisition cost is $100, we will not be able to scale. We defined our metrics around specific customer acquisition costs and lifetime value of the customer ratios. We figured out how to make our model scalable by pouring through the financial statements of our competitors and examining what we can do to modify our operations to be effective. We also track how customers are using our product. And if customers stop using the product, we will find ways to keep them engaged.”

Case Analysis

Target a large, rapidly growing global market. A company seeking to reach $100 million must target a market that is well over $1 billion in revenue because the maximum market share it could achieve is likely no more than 10%. A much larger market leaves room for error. Looker’s decision to target a $20 billion market is helpful in its efforts to reach liquidity.

Shift growth vectors as you scale. Looker set ambitious quarterly growth goals and met them consistently. One key to achieving this is for leaders to recognize that their current growth vector is likely to slow down; therefore, in order to keep growing rapidly, a startup must target new growth vectors before the old ones mature. In its transition from serving investment banks to Facebook users to Fortune 200 financial services firms to Europe, Looker has been able to sustain its rapid growth.

Invent a scalable business model. In Stage 3, startups should operate so that their selling costs drop and the value of their product to customers rises as the company grows. Looker’s CEO is very conscious of this goal and appears to be using a disciplined financial model to keep the company on a path to profitability. If Looker does go public, it will become apparent whether he succeeded.

Less Successful Case Study: Snowflake Computing Grows Fast, But Is Losing Money

Introduction

San Mateo, California-based data warehousing cloud service provider Snowflake Computing was valued at $1.5 billion when it raised a whopping $263 million in January 2018. That trend was good for Snowflake, which offered data warehousing as a service through Amazon’s AWS. Demand for Snowflake had been spiking; its customer count for the year ending January 2018 was up 300% (including Capital One and Nielsen) and investors had plowed $473 million into the company since its 2012 founding. Companies use data warehousing to store and analyze their data to find useful insights such as from machine learning algorithms. Snowflake’s CEO, Bob Muglia, was a 20-year Microsoft veteran who was responsible for its $16 billion Windows Server, SQL Server, System Center, and Azure products. Muglia said “it’s a $15 billion market, according to IDC, but the big data portion that uses open source database Hadoop is only $1 billion to $2 billion. That segment is limited because customers find it difficult to work with.”

Case Scenario

In June 2018, Muglia spoke with me about how Snowflake had grown in the four years since he joined as CEO. And a key reason for that growth was Snowflake’s compelling value proposition to companies; in a nutshell, the product did more of what customers wanted at a small fraction of the price of competing products from Oracle and SAP. Snowflake was growing rapidly by displacing incumbents with a service that did more and cost less. An example was Capital One (which also invested in Snowflake). According to Muglia, “Capital One was way ahead of the crowd. In 2013, its CEO decided to move its entire IT operation into the cloud and that process is likely to be complete this year. The CEO wanted to change the culture of the company. He thought that technology was so meaningful that Capital One needed to be more integrated into Silicon Valley.” Amazon and Microsoft both offered data warehousing, but Capital One picked Snowflake. “They don’t take full advantage of the cloud and Capital One was looking for a shift forward. They concluded that Teradata could not take them into the cloud. And they picked Snowflake because it could run 250 concurrent data analysis queries, compared to 60 for Teradata, at a much lower price (25% to 30% of what Teradata charges).”

Snowflake saw itself as sprinting to liquidity, “We are definitely at Stage 3. Since I joined in June 2014 we have grown from 34 people to 450 and we are on track for $100 million in 2018 bookings. We have been tripling every year. Stages 1 and 2 overlapped. We were working on our product and business model simultaneously.” Snowflake maintained a consistent approach to winning customers. “Our sales strategy is direct: we let customers evaluate and sign up for the service online followed by a capacity purchase, when a sales person encourages customers to make a 24-month purchase if they are happy following the product evaluation,” he explained. Snowflake’s growth came from different groups of customers as it became larger. “Three years ago our customers were already using AWS—companies in the entertainment, media, online gaming, and technology industries. Later we began to focus on traditional enterprise customers—companies in financial services, manufacturing, oil and gas, and retail—that were converting from on-premise to the cloud. They were switching to Snowflake from Netezza (which was acquired by IBM) and Teradata boxes,” Muglia explained.

Even though Snowflake said it was in Stage 3, it remained to be seen whether it could make a profit, suggesting to me that Stage 2 was a work in process. As Muglia said, “We have positive gross margins but our sales and engineering costs make us unprofitable. And when we hire new sales people, it takes time for them to bring in new customers. As sales territories mature and we get bigger, our cost of goods sold and cost of sales will decline and we will be on a path to profitability.”

By November 2018, it was clear that investors were happy to invest in Snowflake despite the absence of a scalable business model. In October 2018, Snowflake raised $450 million, bringing its 2018 total capital raised to $713 million. Between January 2018 and October 2018, Snowflake’s valuation soared from $1.5 billion to $3.5 billion. CFO Thomas Tuchscherer said that the increased valuation was “driven by the growth numbers of almost quadrupling the revenue and tripling the customer base.”

Case Analysis

Snowflake was growing rapidly and had raised a significant amount of capital. Its growth trajectory had evolved as it scaled. So why was it a less successful case? Muglia said that the company was generating negative cash flow due to its high marketing and other operating expenses. This raised the possibility that Snowflake was keeping its prices below the competition’s yet was not achieving efficiencies in key processes such as marketing, selling, service, and product development as it grew. What’s more, Snowflake appeared to be dependent for growth on hiring new salespeople who were expensive to train, took time to reach full productivity, and tended to leave their employers, creating the need to hire new sales people to replace them. By November 2018 it was unclear whether Snowflake would be able to go public without being profitable. However, the month before, its investors sent a strong signal that rapid growth, not profitability, was what mattered most.

Principles

- Do

Set aggressive growth targets and employ disciplined operating strategies to meet them consistently.

Recognize that current growth vectors may mature quickly and therefore keep investing in new growth vectors.

Experiment with sales, marketing, service, and product development approaches that will cost less as the company grows.

- Don’t

Pour gasoline on a business model that does not scale efficiently.

Stage 4: Running the Marathon

Exceed quarterly investor expectations. Public companies are graded every quarter. If they exceed revenue and profit growth targets and raise their forecasts for these variables, what I call “beat and raise,” investors applaud. Otherwise, the stock price can take a nasty hit. CEOs must manage their communications with investors and employees so that they predictably beat and raise. And that comes from carefully developing and executing a sustainable growth trajectory that yields results for which the entire company is accountable.

Invest in future growth. Founders are typically much better at identifying and investing in new growth opportunities than public company CEOs. Conversely, most such CEOs have little experience successfully creating new businesses from scratch. To run the marathon, founders must develop the skills needed to beat and raise while enhancing the scale at which they exercise their ability to identify and profit from new growth opportunities.

Success Case Study: Amazon’s Value Surges from $0 to $825 Billion in 24 Years

Introduction

In 1994, Seattle-based Amazon was an idea in the mind of a hedge fund executive. 24 years later it was a $178 billion (2017 annual revenue) company worth $825 billion, with a stock price that had risen at a 37.6% average annual rate between its May 15, 1997 IPO price of $1.96 a share to $1,710 by July 6, 2018. By 2017, Amazon had broadened its product and geographic scope from the online book selling service to become far more diversified. “Online product and digital media content sales accounted for 61% of net revenue in 2017; followed by commissions, related fulfillment and shipping fees, and other third-party seller services (18%); Amazon Web Services’ cloud compute, storage, database, and other service offerings (10%); Prime membership fees and other subscription-based services (6%); product sales at Whole Foods and other physical store retail formats (3%); and advertising/cobranded credit cards (3%). International segments totaled 33% of Amazon’s non-AWS sales in 2017, led by Germany, the United Kingdom, and Japan.”

Amazon’s founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, the son of a teenage mother, loved gadgets as a child, was his high school valedictorian, a graduate of Princeton, and a hedge fund star who quit to start an online book seller in Seattle. Bezos “showed an early interest in how things work, turning his parents’ garage into a laboratory and rigging electrical contraptions around his house.” He was valedictorian of his Miami high school class, graduated from Princeton summa cum laude in 1986 with a degree in computer science and electrical engineering, and worked at several Wall Street firms. In 1990, he became the youngest senior vice president at the investment firm D.E. Shaw. In 1994, he quit to start Amazon. As he said, “The wakeup call was finding this startling statistic that web usage in the spring of 1994 was growing at 2,300% a year. You know, things just don’t grow that fast. It’s highly unusual, and that started me about thinking, ‘What kind of business plan might make sense in the context of that growth?’” After making a list of the top 20 products that he could potentially sell on the Internet, he decided on books because of their low cost and universal demand.

Case Scenario

Despite minimal profitability, a key to Amazon’s success has been its growth trajectory. Between 1995 and 2018, that trajectory brought Amazon into new customer groups, new products (both built internally and acquired), new geographies, and new capabilities. For example, Amazon started selling books online; broadened its online product portfolio; turned its internal computer systems into a service (Amazon Web Services); made its own hardware devices such as the Kindle and Echo; developed its own video content; acquired a leading grocery store chain; and through acquisitions and a joint venture targeted the markets for health care and pharmaceuticals retailing.

Amazon used the capabilities that enabled it to succeed with selling books online to selling other products there. Amazon moved into selling electronics, which caused consumers to try out the products at retailers liked Circuit City before purchasing them on Amazon, and extended its product line to home goods and shoes (it paid $850 million to acquire Zappos in 2009) among many others. In the early 2000s, Amazon decided to extend its own computer systems to offer other companies its AWS cloud service. Once people started developing apps for the iPhone, AWS became the place to host these apps. AWS became a nearly $20 billion business that generated much of Amazon’s profit. AWS also formed the basis of its advertising technology business that helped other shops identify potential customers. Amazon also built its own hardware, including the Kindle e-reader, which launched in 2007; it entered the tablet market with the Amazon Fire HD in 2012; the video and audio streaming marketing in 2014 with the Amazon Fire TV; and in 2015 Amazon launched its digital home assistant device, the Amazon Echo. Amazon created its own content through Amazon Studios, which launched in 2010. By 2017, one of its movies, Manchester by the Sea, won two Oscars. Amazon made dozens of acquisitions including Twitch, which enabled Amazon to compete with YouTube. Amazon got started in the grocery delivery business in 2007 through AmazonFresh, which spent six years working out logistical problems in a Seattle suburb before launching in Los Angeles and San Francisco. In 2017, Amazon acquired Whole Foods for $13.7 billion. In 2018, Amazon, through a partnership with JP Morgan and Berkshire Hathaway, started a venture to reduce corporate health care costs and spent about $1 billion acquiring a startup PillPack, dedicated to lowering the price consumers pay for drugs.

Case Analysis

In 2018, Amazon was the most successful company still being led by its founder. An important element of Amazon’s success was its ability to sustain growth that exceeds 20% per year even as it approached $200 billion in annual revenue. A key reason for its sustained high growth rate was its ability to produce quarterly revenue gains that exceeded investor expectations while investing in new businesses through a combination of internal product development, partnerships, and acquisitions that tapped into large market opportunities. Moreover, Amazon’s growth trajectory led to gains in its market share because Amazon offered customers greater value than its rivals and it performed activities to deliver that value consistently at global scale.

Less Successful Case Study: Blue Apron Stock Plunges As It Burns Its Cash Pile

Introduction

Manhattan-based Blue Apron, founded in 2012, assembled and delivered “meal kits:” prepared ingredients and a recipe that consumers could follow to make at home. It offered two delivery options: a two-person meal plan (all the fixings for three meals for two people for $59.94) and a family plan. Blue Apron shares fell 64% between July 6, 2018 and the stock’s trading debut in June 2017, and 29% of its shares were sold short as of May 31, 2018. While Blue Apron’s revenues had grown at a 124% annual rate since 2014 to $881 million in 2017, its negative free cash flow had soared from $21 million to $277 million and it had a mere $204 million in cash as of March 2018 and $125 million in long-term debt.

Matt Salzberg founded the company and took it public. In high school and college (Harvard), Salzberg aspired to be an entrepreneur. He worked three years at Blackstone before entering Harvard Business School. Salzberg joined Bessemer Venture Partners after HBS to learn more about startups. During a happy hour for Boston-based sales analysis software provider Insight Squared, Salzberg met a technical consultant named Ilia Papas. They started a crowd-funding platform for research scientists that raised $800,000 in seed funding from Bessemer and failed. While working together, Papas came to work after spending hours buying and cooking Argentinean-style steaks. “Wouldn’t it be awesome if someone delivered you the ingredients in the right amounts?” he asked Salzberg. This is how they said they founded Part & Parsley which later changed its name to Blue Apron. Salzberg raised a $3 million Series A investment round led by Bessemer and First Round Capital. Blue Apron went public in June 2017 but in November 2017 Salzberg was replaced as CEO by a finance expert, Bradley Dickerson, who was then Blue Apron’s Treasurer (since January 2017) and its Chief Financial Officer since February 2016. Before Blue Apron, Dickerson was Under Armour’s CFO from December 2014 to February 2016.

Case Scenario

Blue Apron’s financial performance suggested that there was a gap between its belief about the profit potential of its market and its ability to capture that value through its growth trajectory. Blue Apron believed that its market opportunity was broad due to “the quality of our product, the meaningful experiences we create, and the deep, emotional connection we have built with our customers; this positions us well to grow in the dynamic and high-profile category in which we operate.” In February 2018, Blue Apron believed it participated in the global grocery and restaurant industries. Blue Apron estimated that the U.S. grocery market was $780 billion and the global grocery market was “more than eight times larger.” And the company estimated that the annual U.S. restaurant market totaled $540 billion and the global restaurant market was “almost five times larger.”

Blue Apron struggled to retain customers and to get those customers to keep using its service after they signed up for it. The company warned of this problem and gave an example of how it affected its results. According to the company, “If we are unable to retain our existing customers, cost-effectively acquire new customers, keep customers engaged, or increase the number of customers we serve, our business, financial condition, and operating results would be materially adversely affected. For example, the number of our customers declined to 746,000 in the three months ended December 31, 2017 from 879,000 in the three months ended December 31, 2016, and our revenue declined to $187.7 million from $215.9 million in those periods.”

Blue Apron’s financial results suggested a company that poured gasoline onto a business model that was not scalable and remained so after it went public. According to its IPO prospectus, Blue Apron ended March 2017 with almost $62 million in cash, having burned through $20 million that quarter, suggesting that it would not have made it through 2017 without its IPO. The first mistake Blue Apron made was that its service did not address a source of significant customer pain: for most subscribers, deciding what to make for dinner, shopping for the ingredients, and cooking them was not a problem they were desperate to solve every week for the rest of their lives. To be sure, Blue Apron sales soared 10-fold between 2014 and 2016 to $795.4 million while its net loss increased 16% from 2015 to $54.8 million in 2016. Sadly, its growth did not lead to lower costs. For example, its marketing expenses, spent on television, digital and social media, direct mail, radio, and podcasts, soared 10-fold to $144.1 million between 2014 and 2016. And as it grew, its ingredients and other costs of goods sold rose as a percent of sales, resulting in a decline in its gross margin from 35% to 31% between the first quarter of 2016 and 2017.

If these diseconomies of scale and potentially high costs were not bad enough, Blue Apron’s business lacked what Warren Buffett called a moat. Blue Apron’s idea attracted competition from rivals including HelloFresh, Sun Basket, and “the vegetarian-focused Purple Carrot,” according to the New York Times. Perhaps this competition was a factor in its slowing growth. After all, as the Times noted, “Its average order value for the first three months of 2017 shrank slightly from the same period a year ago, to $57.23. Both the number of orders per customer and the average revenue per customer also fell slightly in the first quarter of this year compared with the first quarter of 2016.”

Blue Apron’s inability to deliver what customers ordered on time seemed to have contributed both to its loss of customers and the replacement of Salzberg as CEO. In August 2017, Blue Apron’s stock lost 17% of its value after a disappointing financial forecast for the second half of 2017. Blue Apron’s warehouse inefficiencies cascaded into unhappy customers who quit the service and marketing challenges also hurt its revenues. Specifically, Blue Apron encountered “unexpected complexities” in transitioning from its previous New Jersey warehouse to “a new, highly automated” one. Salzberg laid the blame on “over 5,000 employees who are all being trained in new processes and new systems that are more advanced than the systems that they are used to working with. The training produces costs [since people being trained] are not doing day-to-day proactive work.” The result was a deterioration in the percentage of orders that arrived on time and with all the correct ingredients (in full), the company said. Failed first orders caused more customers to leave the service, which meant that the company wasted marketing dollars. And Blue Apron’s plan to reduce its marketing expense as a percent of revenue from 20% to 15% required the company to slash its revenue forecast from $421 million in revenue in the second half of 2016 to between $380 million to $400 million for the second half of 2017. By November 2, 2018, Blue Apron’s stock had fallen to $1.41 a share and it was hoping that an October 2018 partnership to distribute its products with Jet.com , a Walmart subsidiary, would help the company survive.

Case Analysis

Solve an important customer pain point. One way that startups can boost their odds of success is to solve a problem that customers find important. More specifically, startups should solve a problem that is so painful that customers would gladly pay for its solution, that other companies are not addressing, and that the startup is uniquely skilled at solving. Blue Apron’s first mistake was deciding to offer customers a vitamin—a solution to a relatively unimportant problem.

Outperform rivals in satisfying CPC. Once startups have picked the right problem, they must investigate the factors that customers will use to decide whether to purchase the startup’s product and deliver a product that wins on those CPC. Blue Apron has grown revenues rapidly, suggesting that customers are willing to try its service. Yet its declining profitability reflects the high cost of customer churn coupled with the pressure to lower its prices thanks to rival services.

Lower costs and boost customer perception of value as you scale. As I discussed earlier, companies should master the second stage of scaling, lowering their costs and boosting the value to customers of their product as they get bigger. Blue Apron skipped Stage 2 and went on to Stage 3. In Stage 4, it is visibly failing to master the complex challenge of fulfilling hundreds of thousands of orders correctly, leading customers to quit and revenues to decline.

Invest in capabilities to retain customers as you scale. To keep customers happy, companies must build capabilities that make customers loyal and excited to recommend the company to others. Blue Apron failed in building the right capabilities such as an effective and efficient supply chain. Thus, it suffered a decline in accurately fulfilled orders. It remains to be seen whether the company can solve these operational problems and prove to investors that it can grow profitably.

Principles

- Do

Solve an important customer pain point.

Consistently outperform rivals in satisfying CPC.

Invest in capabilities that enable high customer loyalty.

Beat and raise each quarter.

Invest in new growth opportunities as you scale.

- Don’t

Do the opposite of these five principles.

Growth Trajectories Success and Failure Principles

Summary of growth trajectory principles

Scaling Stage | Dos | Don’ts |

|---|---|---|

1: Winning the first customer | Focus product development on relieving intense customer pain. Collaborate with early customers you already know to develop and deliver a better product that relieves the customer pain. Sell to a customer group that feels this pain more intensely than others. Use a sales strategy that has the potential to scale efficiently. | Build the initial product around a vitamin. Cold call potential customers before doing research to identify groups who will need the product the most. Sell the product through a long, CEO-led consultative process. |

2: Scaling the business model | Target new growth vectors with significant profit potential. Research whether the startup’s product can outperform rivals on the new growth vector’s CPC. Win market share by applying capabilities at which the startup excels. Market, sell, and service customers in the new growth vector in ways that lower the cost of those activities as the startup scales. | Assume that a large market opportunity means big potential profits for the startup. Assume that the startup’s ability to win market share in its core market will lead to similar gains in the new market. Grow through higher marketing, sales, and service costs and lower prices. |

3: Sprinting to liquidity | Set aggressive growth targets and employ disciplined operating strategies to meet them consistently. Recognize that current growth vectors may mature quickly and therefore keep investing in new growth vectors. Experiment with sales, marketing, service, and product development approaches that will cost less as the company grows. | Pour gasoline on a business model that does not scale efficiently. |

4: Running the marathon | Solve an important customer pain point. Consistently outperform rivals in satisfying CPC. Invest in capabilities that enable high customer loyalty. Beat and raise each quarter. Invest in new growth opportunities as you scale. | Do the opposite of these five principles. |

Are You Doing Enough to Create Sustainable Growth Trajectories?

Is your startup solving a problem that is so painful that potential customers would be willing to pay for an effective solution?

Do you know which growth vectors your startup will follow to get big and keep growing at each of the stages of scaling?

Does your company continue to invest in new growth opportunities to sustain its rapid growth at each stage?

Conclusion

Creating and executing sustainable growth trajectories is essential to keep a startup growing from an idea into a large publicly-traded company. To do this successfully, leaders must be prepared to follow the principles outlined in this chapter to reinvent their growth trajectories as the company gets bigger. At the core of effective growth trajectories are strategic decisions about which customers to serve and how to build, market, sell, and service those products so that the startup can win customers, keep them buying over time, and attract new customers who remain loyal as the company grows. In Chapter 3, I will tackle one of the most challenging and time-consuming jobs of a startup CEO: how to raise the capital needed to fund growth.