Estimate amount of capital needed. The first step in raising capital is to estimate how much money the startup needs. The amount required will vary depending on the startup’s industry, business model, and scaling stage. The estimate should be based on a detailed analysis of all the costs the startup will incur to achieve its objectives for that stage, and typically it makes sense to consider doubling that bottoms-up estimate to provide a cushion for unexpected outcomes.

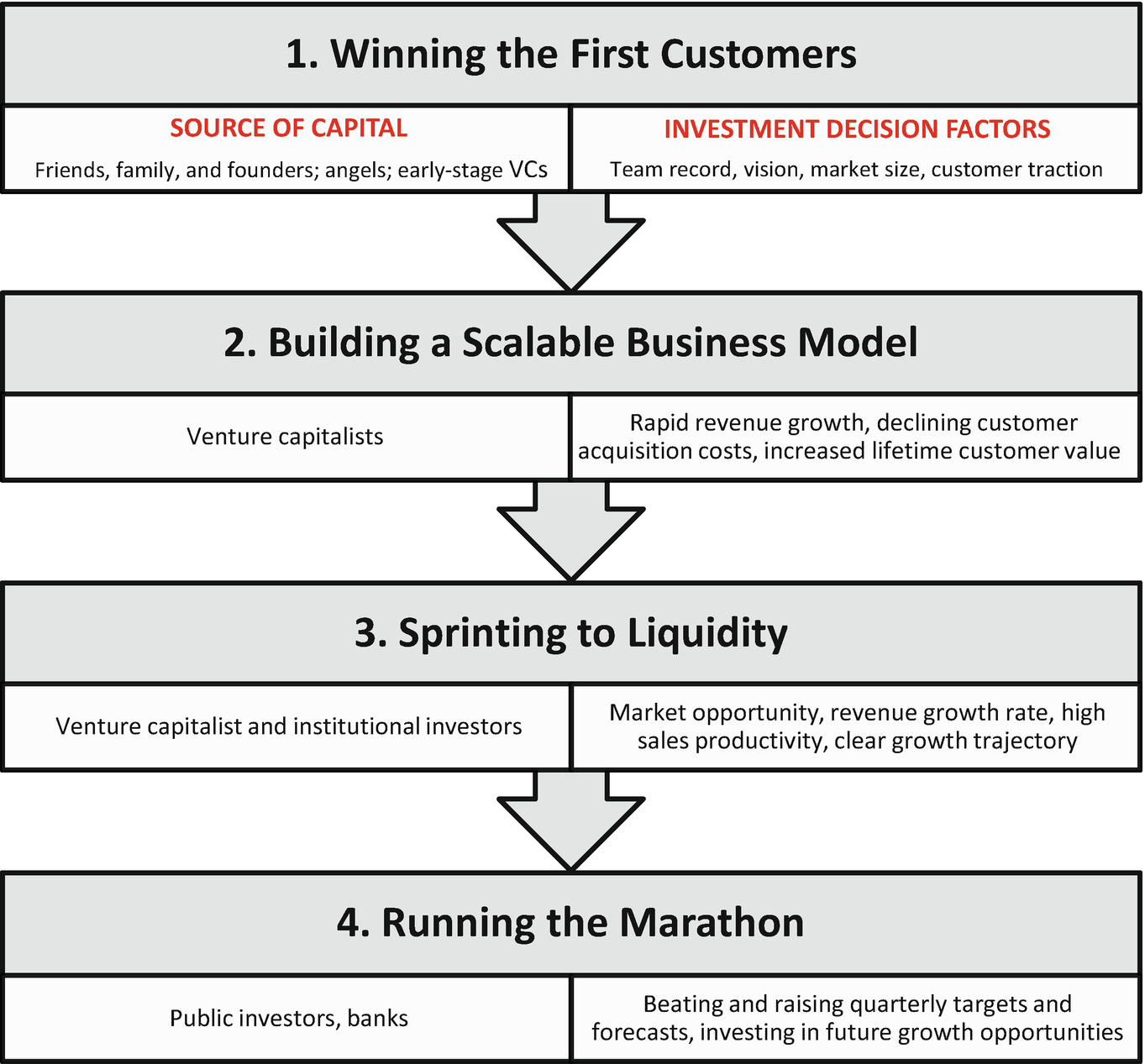

- Identify potential sources of capital. The sources of capital vary by scaling stage. One key factor that affects the CEO’s choice of capital source is whether the founder and management team have previously achieved successful outcomes for investors. For example, if a CEO has already enriched venture capital investors in a previous startup, those investors will be far more willing to invest early in that CEO’s next venture.

Stage 1: A first-time entrepreneur will need to approach friends and family, and seek grants, angel investors, or crowdfunding. A previously successful founder will be able to self-fund or go to venture capitalists at this initial stage. Indeed, depending on the amount of time it takes to generate initial revenues from first customers, startups may end up seeking capital from seed stage, Series A, and possibly Series B venture capital providers.

Stage 2: Many startups do not make it past the first stage. But those that do, whether they are run by serial or first-time founders, will seek capital for this round from venture capital firms that are comfortable with later-stage investing. Moreover, many startups continue to receive funding without having a scalable business model because investors are convinced that the company can go public due to its rapid growth, despite requiring enormous amounts of capital to fund their losses.

Stage 3: When a startup has proven it has a scalable business model and a large untapped market opportunity, it will have an easier time raising capital from venture capitalists and institutional investors who envision a relatively risk-free path to high returns from an IPO within the next year or two.

Stage 4: Following a company’s initial public offering, CEOs usually have a much easier time raising new capital, either by selling stock, borrowing from banks, or selling bonds.

- Understand investor decision criteria . Investors decide whether to invest depending on specific factors that vary by stage.

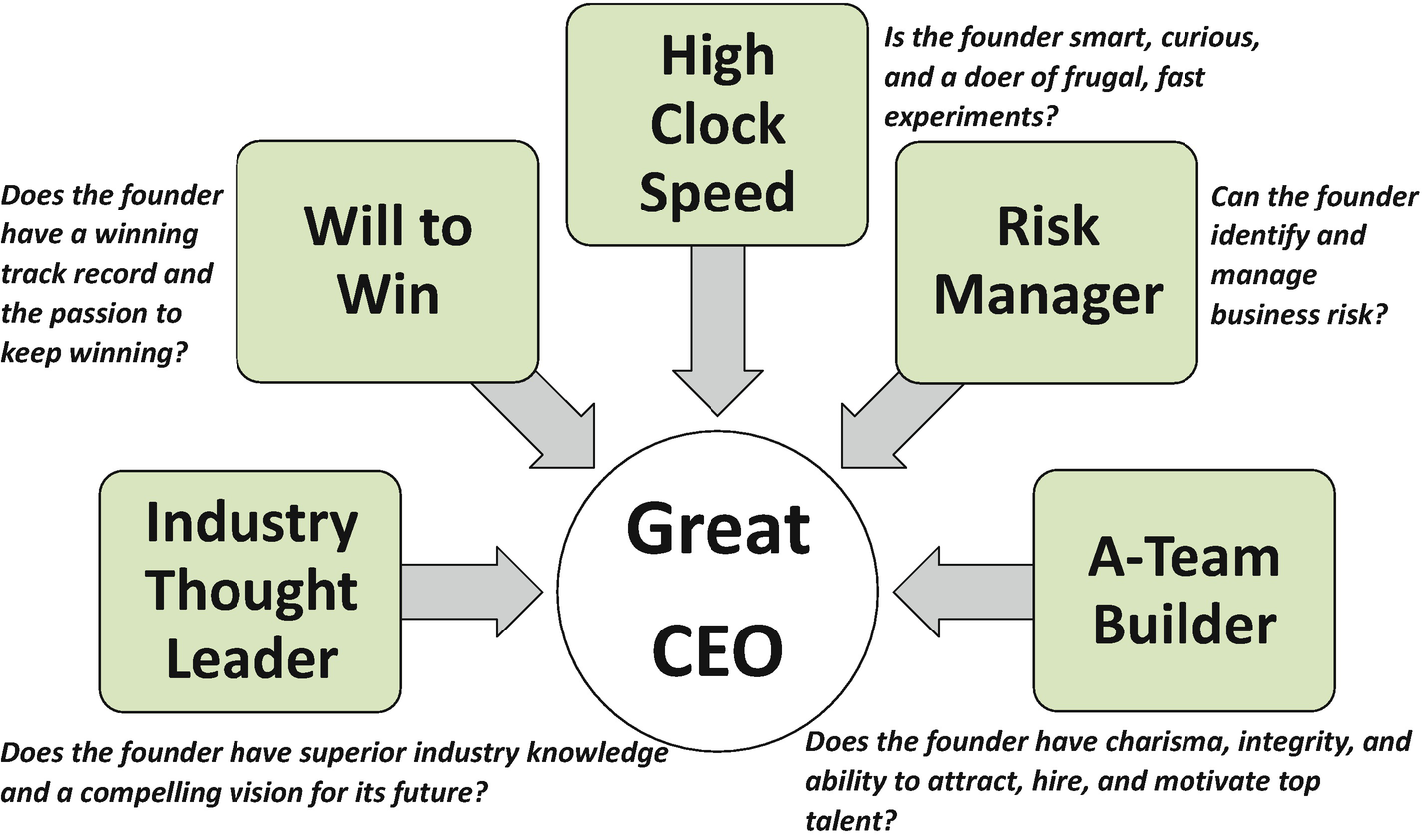

Stage 1: As illustrated in Figures 3-2 and 3-3, investors’ decision criteria at Stage 1 are the least tangible. Before the company has generated any revenue, investors will assess whether the startup is targeting a market that has the potential to get big quickly and whether its founder could be a great CEO. As a startup gains a handful of early customers, investors will conduct in-depth due diligence by asking the early customers how satisfied they are with the company and its product, how likely they are to buy more from the company, and whether they see the company’s solution as broadly useful for many potential customers.

In Stage 2, investors seek signs that the company has a scalable business model that will enable the startup to grow quickly while its incremental costs for marketing, selling, and servicing customers drop, and the profit generated by each customer relationship grows because those customers buy more of the startup’s product and keep buying over time.

At Stage 3, investors provide funds based on the size of the market opportunity; the demonstrated ability of the company to scale efficiently, as measured by a declining cost of customer acquisition; a high customer retention rate; the startup’s ability to sell more to existing customers; and its previous record of setting and exceeding quarterly business objectives.

At Stage 4, investors will purchase the company’s stock if it persistently exceeds revenue and earnings expectations while raising its forecast and investing successfully in future growth trajectories to sustain rapid revenue growth.

Develop and deliver investor presentation . CEOs generally communicate with potential investors using a pitch deck, usually a series of PowerPoint slides. CEOs seek feedback on their presentations from mentors before delivering them to potential investors. And the topics addressed in these presentations are intended to address the investment decision criteria of potential investors at each scaling stage.

Negotiate and finalize deal structure and valuation . If the startup satisfies investors’ questions, it is likely to receive offers to invest. The founder and the investors will tussle over specific deal terms including the structure of the investment, generally some form of convertible preferred stock that pays a quarterly dividend and at maturity is converted into a specific number of common shares; the valuation of the company prior to the investment, which determines what percent of the company the investors will receive in exchange for their money; liquidation preferences, which specify how the proceeds of a sale of the company will be divided; and how many board seats the investor will receive.

Strategies for raising capital at each scaling stage

Stage 1 investment criterion: big potential market

Stage 1 investment criterion: great CEO

Takeaways for Stakeholders

- Startup CEO

Target a market opportunity with the potential to enable the startup to get large quickly.

Seek out design partners that suffer acutely from the problem your startup seeks to solve.

Build, sell, and service a product that customers are eager to purchase.

Provide service and new products that keep customers wanting to purchase more.

Find potential investors who can help the startup grow by providing capital and advice that will help the startup grow.

Set and exceed ambitious quarterly performance goals as the startup scales.

- Investors

Assign a partner to the startup’s board who can advise the CEO on how to realize the startup’s vision and meet shorter- term growth milestones.

Help the startup exercise scaling levers, particularly assisting with hiring key executives, finding customers and partners, and raising sufficient capital.

Capital-Raising Success and Failure Case Studies

In this section, I offer case studies of capital-raising strategies used by successful and less successful startups at each scaling stage, analyze the cases, and extract principles for helping founders to raise growth capital at each stage.

Stage I: Winning the First Customers

Customer profitability : Offer customers a product that is so valuable to potential customers that they are willing to pay enough money upfront to make the company profitable.

Founder’s funds : Create a founding team that can fund the early stages of the company from their own funds, possibly due to previous startup success or from borrowing.

Previous VC-backed exit : As mentioned, an entrepreneur seeking to raise seed capital for a new venture could receive funding from a VC firm if the CEO has already enriched that VC thanks to a prior successful sale or IPO.

Absent these paths, the CEO will likely need to try to persuade the capital sources mentioned above (such as friends and family, crowd-funders, business plan competitions) that it is worth taking a risk on funding the startup’s first stage of scaling.

The cases that follow highlight successful and less successful handling of the challenges such a CEO must overcome.

Success Case Study: As JASK Wins Customers, It Raises Capital from Kleiner Perkins

Introduction

Founded in 2016, San Francisco and Austin, Tex.-based JASK helped organizations analyze threats to their IT operations. JASK (a contraction of “Just Ask”) “fuses collected data with alerts from existing security solutions and applies AI and machine learning to automate the correlation and analysis of threat alerts. JASK Insights deliver the most high-priority threat incidents for streamlined investigations and faster response times, guiding the security operations center (SOC) analyst to the most critical tasks and freeing them to proactively identify new threats.” By July 2018, JASK had raised $40 million in capital as it aspired to reach $10 million in 2018 revenue. In March 2018, Greg Martin, the CEO of JASK, told me that the company was winning business from HP, IBM, and Splunk in 30% of its deals and expected that share to grow. Martin was an ex-FBI, Secret Service, and NASA hacker. As he explained in a March 2018 interview, he led the SOC for ArcSight, which went public in 2008 before HP acquired it in 2010 for $1.5 billion. Martin also founded cyber threat intelligence company ThreatStream in 2012, now known as Anomali (it’s raised over $96 million). Martin started JASK in January 2016 to fix the flaws in products from IBM, HP, and Splunk that show security officers “thousands of alerts—think of them as dots—but failed to connect them. To deal with the volume, SOCs threw more bodies at the problem and suffered from wasted time to connect the dots from thousands of alerts that machines are now capable of handling.”

Case Scenario

In 2018, JASK was gaining share of a growing market which had eased, though not eliminated, all the challenges of raising $40 million of capital in its first stage of scaling. JASK and its rivals were vying for a $5 billion market—expected to reach $6 billion by 2023—for security intelligence and event management (SIEM) software that tracked and analyzed cyberattacks. JASK was in the first stage of scaling. As Martin explained in a July 2018 interview, “We are at the product/market fit stage where we want to win 50 to 100 customers. We typically want to win $100,000 per contract and are not focused at all on Stage 2. We pay out all of our revenues to our sales team, which is not sustainable.” JASK won its first customers from companies that its founders knew well before they started the company. “You can’t afford to try a bunch of experiments; you have to spray and pray. We tried to sell to five to 10 customers that were friends and family, marquee names that we hoped could become reference customers. The earliest customers happened to be in finance and health care, and we expanded into those verticals,” he said.

Customers bought from JASK because they believed the product would help them solve current and future problems and due to JASK’s meticulous customer support. According to Martin, “Our first 20 customers bought because we offer a future-proof platform that meets their needs now and will continue to do so in the future. These days 80% of Chief Information Officers see the value of the public cloud because of the cost savings to them. And we offer world-class support, letting customers talk to the people who developed our product.” JASK’s sales process is based on both inside and outside sales. As he said, “When we sell to companies with fewer than 15,000 employees, we can use our inside sales people who are based in Austin. For larger clients, we have outside sales representatives in eight regions around North America.” In mid-2018, JASK won its biggest contract, worth $2 million over three years, from a “Fortune 100 company.” As Martin said, “We came in late in the process, competing against Splunk and FireEye. HP ArcSight had been there for 10 years. The company wanted the next generation. They had used Splunk, which was proposing an $8 million , eight-year contract, but an internal advocate for JASK added us late in the process. We wrapped ourselves around the customer and addressed their transition process. There was a vote of all the people involved and the Chief Information Officer and Chief Information Security Officer finally signed off.”

JASK had a relatively easy time raising nearly $40 million in capital. Indeed, in June 2018, it raised a $25 million Series B round led by Kleiner Perkins and in 2017, it raised a $12 million Series A round led by Dell’s venture arm and TenEleven Ventures. Battery Ventures provided its initial $3.4 million in funding. As Martin explained, “It took four months using a PowerPoint presentation to raise the initial round from Battery, which was much easier because of our prior track record of success. We had a team with a strong background; our team brings together decades of experience solving real-world SOC issues from ArcSight, Carbon Black, Cylance, Netflix, Cloudera, and the U.S. counter intelligence community, and a novel approach to a large addressable market. Our Series A round raised a relatively large amount of money—such rounds range from $6 million to $12 million—due to strong competition among investors. We had product/market fit and 10 customers.” The Series B round was quite challenging. “The bar of success is raised high for collecting the $15 million to $30 million provided by a Series B. Investors expect revenue of $1 million per quarter and annual recurring revenue of $2 million to $3 million, with few exceptions. The investors talk to at least six customers and partners to find out why they purchased.” Whatever Kleiner Perkins found in its due diligence made it want to put its General Partner, Ted Schlein, on the JASK board. As Schlein said, “Through advanced AI and machine learning, JASK frees security analysts from onerous data review to focus on investigating and responding to the most critical threats, improving efficiency, and reducing organizational risk exposure.”

Case Analysis

Field a successful founding team.

Focus on unresolved customer pain.

Hire people with expertise and passion for solving the problem.

Design, deliver, and service a product that customers love.

Less Successful Case Study: With $37 Million in Capital, OmniSci Gradually Gets Its Product Up to Speed

Introduction

Founded in September 2013, San Francisco-based OmniSci (which changed its name from MapD in October 2018), provided a database that helped companies analyze and visualize huge amounts of data very quickly. OmniSci had taken about five years to reach the end of the first stage of scaling and as of July 2018 had gradually raised $37 million to fuel its growth. OmniSci described itself as “the extreme analytics platform used in business and government to find insights in data beyond the limits of mainstream analytics tools. The OmniSci platform delivers zero-latency querying and visual exploration of big data, dramatically accelerating operational analytics, data science, and geospatial analytics.”

OmniSci’s cofounder and CEO, Todd Mostak, started programming in his early teens but ended up with a degree in economics and anthropology from UNC, earned a Masters’ degree in Middle Eastern Studies from Harvard, and became fascinated with analyzing the locations from which Egyptian tweets emanated during the Arab Spring. He spent 2013 as a researcher at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab where he wowed his professors with the demo he developed for a database that could visualize billions of points on a map. P&G, a company participating in MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program, was impressed and wanted to buy the product. The company was an MIT spinout started because its product targeted a real point of customer pain. As Mostak said in a July 2018 interview, “The demo was not ready for production but the fact that it fit a major need made me think I should work on it. In September 2013, I spoke with a friend from Harvard Law School and decided to leave MIT and start the company, which I did in January 2014.”

Case Scenario

OmniSci’s gradual growth paralleled the pace of its capital raising. To be sure, OmniSci was targeting a large addressable market. Adding up all the segments in which it competed in July 2018 yielded $70 billion worth of revenues from three markets: $40 billion from analytics databases, $25 billion from business intelligence, and $5 billion from geographic information systems. But OmniSci took its time turning the demonstration version of the product that Mostak had developed at MIT. By July 2018, OmniSci had grown to between 75 and 80 employees and “gotten decent customer traction,” competing against big companies like IBM (Netezza), Oracle, SAP, and Vertica, which HP sold to Microfocus, to win “50 to 100 customers.” OmniSci’s victorious battles resulted from unique capabilities such as real-time analysis of 5 to 100 billion records and rendering capabilities that enable users to pinpoint specific data points on a map, which customers valued. OmniSci’s customers fell into three industries. “We have 8 to 10 telecommunications customers around the world who are using our product to find out why calls are dropped. They are slow to move, but offer us significant revenues,” he said. In addition to defense department and intelligence clients, companies also use its product to analyze real-time purchases to pick winning investments. “We have hedge fund and investment banking clients that use OmniSci to analyze stock ticker data and credit card transactions. They analyze 10% to 30% of all transactions in real time to see which companies are enjoying upticks in purchases. Our product lets them refresh their analysis every 30 minutes instead of daily.”

Its journey to that end was impeded by several factors: the company’s founder had never started a company before, the product was technically complex, and its earliest customers were cautious in their collaboration with the company. Initial money came from family and a business plan competition. As Mostak said, “We got loans for between $5,000 and $10,000 from our parents. My family was questioning why I was doing this instead of working for the man. They would have pushed me to take a real job if we had not succeeded. But we won a $100,000 early stage challenge from Nvidia during a period when big data was hot.” Between 2014 and 2017, OmniSci raised more money. “In June/July 2014, we raised $2 million more from Nvidia; after endless meetings they decided to give us more money to develop our product. In March 2016, we raised a $10 million Series A led by Vanedge, a Vancouver, BC-based fund, which was tricky because we were still trying to get product/market fit with potential customers like Verizon. And in February 2017, we raised a $25 million Series B, at which point we had double-digit numbers of customers, some of whom paid over $1 million.” By October 2018, OmniSci had raised a $55 million Series C round of funding led by hedge fund Tiger Global Management. “It was clear that [Series C investors] held a strong thesis around the massive market opportunity in front of our company and were fully aligned with our vision of the disruptive power of GPU-accelerated analytics,” Mostak wrote.

Case Analysis

Their startup’s product will address real customer pain.

They can turn an idea into a product that will produce tangible benefits for which customers will pay.

The market for that product will be worth billions of dollars.

They can build and run an organization that can design, build, market, sell, and service products for a growing collection of customers.

To OmniSci’s credit, it was able to overcome the first three challenges, succeeding despite significant obstacles to raise enough capital to keep the company going until it could begin to generate revenues. And in October 2018, it raised a significant Series C round, indicating that investors found its vision compelling.

Principles

- Do

Focus on a source of unrelieved customer pain that is so high that potential customers would pay for a product to alleviate it.

Form design partnerships with early customers who feel this pain most intensely.

Build a team that cares passionately about building such a product and has the skills needed to make that product a market leader.

Demonstrate that the product targets a large market opportunity.

Seek capital from sources that will care most about contributing to your Stage 1 success.

- Don’t

Assume—without talking to dozens of potential customers—that your unresolved pain is shared at all or, if it is shared, is intense enough to make potential customers pay to relieve it.

Seek to raise capital without conducting in-depth research with potential customers that provides strong evidence that there could be a big market for your product.

Assume venture capitalists will invest in you if your company has a founding team without a track record of turning ideas into large companies or lacks relevant industry expertise.

Stage 2: Building a Scalable Business Model

Reference customers : Investors want to conduct in-depth interviews with a startup’s happiest customers who know the company well and have benefited significantly from its products. Based on these interviews, investors should be convinced that your startup’s reference customers will keep buying more from you and will happily help you win more customers;

Evidence of a large potential market : Investors will also want to be convinced that the market for your product is, or is quickly growing to be, at least $1 billion. Such evidence can come from research reports from analyst firms such as Gartner or IDC. If your company is creating a new product category, such research may not be available, in which case the CEO should provide an estimate of the size of the addressable market based on the number of potential users, the expected purchase frequency, and an estimated purchase price.

Team with strong functional skills : Potential investors will also assess the strength of a startup’s team to reach a conclusion about whether its key functional executives (e.g., Chief Marketing Officer, Chief Technology Officer, and Chief Sales Officer) have a prior track record of building an organization that can boost the efficiency of their functions as the company grows to $100 million in revenue.

Potential for improved efficiency : Investors at this stage will try to assess whether a startup has the potential to grow quickly to $100 million without spending too much money. For example, if the startup’s revenues increase at 200% annually, investors will look for the company to achieve that growth while increasing the number of employees more slowly, say by 50%. To persuade investors that this is possible, a startup should track metrics such as the cost to acquire a new customer, the customer retention rate, the company’s net promoter score, the cost to filter qualified leads from inquiries, the coefficient of virality, and the lifetime value of customers. Moreover, the CEO should have ideas on how to improve the startup’s performance on these measures as the company grows.

Absent these paths, the CEO will likely need to try to persuade the capital sources mentioned above (such as friends and family, crowd-funders, business plan competitions) that it is worth taking a risk on funding the startup’s first stage of scaling.

The cases that follow highlight successful and less successful handling of the challenges such a CEO must overcome.

Success Case Study: Varsity Tutors Raises $107 Million to Target $1 Trillion Market Opportunity

Introduction

A first-time entrepreneur with a knack for turning problems into opportunities was able to tranform an idea into a company that was growing rapidly thanks to his ability to solve difficult operational problems and to keep finding new growth opportunities. The company in question was St. Louis and Seattle-based Varsity Tutors, “a live-learning platform that in minutes connects students with vetted tutors and offers Instant Tutoring that matches students in 15 seconds with tutors in over 100 subjects.” By July 2018, Varsity Tutors had grown from an idea in 2007 to a service with about 500 employees, some 40,000 tutors, and 100,000 customers who could be tutored in 1,000 subjects. Students paid between $60 and $70 per hour, and as of February 2018, the company had facilitated 3 million hours of tutoring, yielding about $200 million in revenue since 2007.

CEO Chuck Cohn discovered the value of good tutoring in high school. As he said, “I had a range of experiences with tutoring—from the incredible experience of raising my honors geometry grade from an F to an A thanks to a great tutor, to working with a French tutor who couldn’t speak English and couldn’t help me, to failing to find a qualified biology tutor in time for a big test despite looking online, asking for referrals, and calling local colleges.” One night in college, I was studying for a Calculus 2 test and I was really struggling with a few key concepts. I was on the verge of failing the exam and probably the class . Thanks to two good friends who explained the concepts in a fundamentally new way, I got a great grade on the test. I realized that had I had access to tutors like my two friends—academically gifted, personable, exceptional communication skills—I would have had a better high school experience. I would have had better grades, enjoyed school more, and been less stressed. I asked my two friends if they would be willing to work as tutors, we haggled over a rate, and eventually came to an agreement. I borrowed a $1,000 from my parents to start the business and Varsity Tutors was born.”

Case Scenario

Varsity Tutors participated in a $100 billion fragmented industry. As he said, “The top 10 companies control 8% market share; the other 92% is controlled by 5,000 mom & pops and one to two million independent tutors.” Cohn saw Varsity Tutors applying its platform beyond school-related tutoring to other skills like do-it-yourself home projects, computer programming, chess, and yoga, which he saw as a $1 trillion market opportunity.

As Cohn devoted more attention to the company, after spending years working full time in investment banking and venture capital during the day while working on the company at night, he figured out how to make Varsity Tutors far more scalable. In 2011, he realized that he could build a large, profitable, fast-growing company. As he said, “The sales process was not standardized, there was no tracking of marketing spend, we were paying tutor interviewers to do nothing because the candidates did not show up, we had a weak website, and the e-mails we sent were no good. I was exposed to great operators and they told me how they would scale.” So, he became its full-time CEO in 2012. He fixed the interaction between students and tutors and improved the overall customer experience, leading to rapid growth.

As a result, he was able to raise $107 million in capital for the company. By 2015, after turning it into a learning platform, Varsity Tutors switched from providing all its tutoring face-to-face to 70% online. The company had a relatively easy capital raising experience. As Cohn said, “I borrowed $1,000 from my parents and was basically profitable from the beginning. In 2014, we raised a $7 million Series A round of capital from two local entrepreneurs whom I asked for advice on how to scale the company. They asked me to pitch and they led the round.” Things got easier from there because he realized that Varsity Tutors was scalable. “In 2015, we had improved our reporting and gotten our online business running. 40 firms contacted us, and we picked the five we respected most, raising a $50 million Series B round from Technology Crossover Ventures, a VC firm that has invested in Netflix, Spotify, Airbnb, and Facebook. They wanted in because we were profitable and growing and we had happy customers because we focused on getting more efficient at identifying great tutors as we scaled,” said Cohn. Varsity Tutors raised more capital in 2018. “In January 2018, we raised another $50 million in a Series C round from Learn Capital, a global ed tech venture capital firm, and The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. They shared our vision of the big opportunity from building a huge online business,” he said.

Case Analysis

To raise capital during the second stage of scaling, founders must provide investors what they want -- a company that’s growing fast and making a profit. While CEOs must spend time raising capital, such financial performance will attract interested investors. It is far easier to select the best investors from a set of interested candidates than to cold call hundreds of potential investors who do not know about the company.

Target a huge market.

Identify flaws in the business model that add cost and customer friction.

Redesign operations to reduce the cost to acquire and service customers and boost customer’s desire to buy more over time.

Design, deliver, and service a product that customers love.

Expand geographic scope through acquisitions and new sales offices.

Select investors who share the CEO’s vision for the startup.

Less Successful Case Study: Tipalti Raises $40 Million As It Ambles to Liquidity

Introduction

By 2018, Palo Alto, California-based Tipalti, founded in 2010 to help improve the way companies make global payments, had raised $60 million. Targeting the $1.9 billion (expected 2025) U.S. accounts payable software market, Tipalti saw itself scaling to liquidity after seven years. Tipalti was established to solve a problem for global online advertising or crowdsourcing networks. They faced a blizzard of complexity in getting funds to payees. Each country had different rules for different forms of payments and fees as well as myriad country-specific regulations to block money laundering and funding of terrorism.

Tipalti cofounder and CEO Chen Amit was a serial entrepreneur. He earned a BSc from the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology and an MBA from INSEAD and had an impressive track record. He founded ECI Telecom’s ADSL business unit and led it to $100 million in sales. He was co-founder and CEO of a business intelligence software supplier and was CEO of Atrica, a Carrier Ethernet company that Nokia-Siemens acquired.

Amit and his co-founder started Tipalti in the summer of 2010 when the president of InfoLinks, an online advertising exchange, told them that mass payments were a pain that needed a solution. Amit wanted to be sure that the market opportunity for helping InfoLinks would be enough to warrant starting a company so they “conducted due diligence to make sure it was a generic need.” The company launched its first version in September 2011 and a year later had signed up 25 customers and employed 15. Tipalti won new customers because of its financial and technical advantages, according to Amit. Tipalti “white labeled” its services, letting customers maintain their brands, but gave them access to its remittance capabilities with “a single line of code” so new customers could be “up and running in half a day.” Tipalti charges customers various transaction fees and partners with leading banks and payment providers as “a layer on top of their payment methods.”

Case Scenario

By 2018, Tipalti was growing rapidly, had 230 customers of which it retained nearly 100%, its revenues were growing at 100% a year, it employed over 100 people, and had raised $60 million in capital. Amit had built an organization of strong functional leaders. As he explained, “Our head of operations worked for a payments startup that was acquired by Fiserv; our head of marketing was previously a vice president of online marketing at NetSuite; our head of sales helped Coupa grow from $1 million to $100 million in revenue; and our head of engineering was hired out of the Technion and has grown into the CTO role. We are now looking for an internal CFO.” Investor and cofounder Oren Zeev helped recruit these talented executives. As Zeev said, “When we were recruiting the head of marketing, he was not looking for a job. But he liked Tipalti’s problem domain, was impressed that it had near-perfect customer retention, and he got a strong message about the value of its product. And Chen comes across as a grownup, not a jerk. It is rare that I sit down with someone who I believe is a good fit for the company and can’t convince him. I have the credibility to convey the message.”

Raising a $30 million Series C round in February 2018 was made easier because Tipalti had become more efficient at marketing. As Amit explained, “Our VP of marketing, hired about three years ago, helped us generate strong interest among potential customers, which we call inbound leads. We used to get 95% of our leads from direct sales calls, so-called outbound, and 5% from inbound. Now 70% are inbound and 30% are outbound.” Zeev said, “At the seed round, I look for the size of the opportunity, the strength of the founder, and the value proposition of the product. When you get to later stages in a company’s growth, you can get data on the customer churn rate, the lifetime value of the customer, and the cost of customer acquisition. We assume a Tipalti customer has an eight-year life and only 1% to 2% churn.”

Zeev , who contributed $21 million of the $30 million round, and Amit saw Tipalti’s potential for scaling thanks to three principles: Tipalti boosted its customers’ productivity, its culture supported high customer retention, and Tipalti was able to sell more to its happy customers. As Amit said, “Tipalti’s near-perfect record of customer satisfaction and retention rates [demonstrate how] much value our service generates for our clients. By modernizing the finance operation, we typically automate 80% of an organization’s AP and cross-border payments workload, freeing the finance team to focus on scaling their business globally and [boosting their] profitability. This funding round enables us to continue [to innovate].” Tipalti’s culture made it clear to employees that customers mattered. As Amit said, “We created a culture driven by our leaders. We hire people who will do a great job for customers. They in turn hire people who share those same values. And as the company has grown to 100 people, we have become more deliberate about articulating and communicating those values.” Customers saw Tipalti as the best product in the industry. Zeev made his investment in part on his belief that Tipalti was delivering on this premise. As he said, “It was a relatively easy decision to continue investing in Tipalti since it’s a category leader. When you talk to Tipalti’s clients like Amazon, GoDaddy, Indeed, Roku, and Twitter, or read the company’s five-star reviews, the consensus is that businesses around the globe love using Tipalti.” Moreover, Tipalti was able to sell more to its current customers. According to Zeev, “The reasons our customers buy more from us is because they start in one division and the product works so well there that other divisions follow. At Twitter, we started in one business unit initially, expanded to three, and today we are being used in seven business units. Other companies made acquisitions and we’re always on the winning side.”

Case Analysis

Tipalti took about eight years for its business model to become scalable. To be fair, Tipalti decided to focus on providing customers with excellent service so they would renew their contracts with the company. In so doing, Tipalti was in no hurry to expand its customer base and it may have struggled to sell efficiently. To Tipalti’s credit, it accelerated its growth in recent years, possibly due to an increase in inbound inquiries from customers that helped reduce its time to close new sales. Nevertheless, Tipalti’s heavy dependence on Oren Zeev’s capital to sustain itself raised questions about whether, perhaps due to the relatively small target market, he was one of the few investors to see high potential returns from Tipalti.

Principles

- Do

Target a market opportunity of at least $2 billion; a larger market is better.

Achieve rapid, profitable revenue growth; these results will attract many potential investors and make it easier to choose the best from among those interested.

Measure operations to identify opportunities to lower the cost of developing, marketing, and selling the product.

Monitor and take steps to assure high customer satisfaction to boost retention rate and increase revenue per customer.

- Don’t

Target a market with less than $2 billion in revenue.

Spend much more money to build, market, and sell than you can collect from customers.

Operate a sales process that requires hiring expensive sales people who take too long to become productive and leave after they are unable to meet their quotas.

Stage 3: Sprinting to Liquidity

It is gaining share in a large market . A market in the tens of billions of dollars growing at double digit rates is compelling to the venture capitalists, private equity firms, and institutional investors who may provide capital at this stage. Moreover, such investors are likely to be heartened if there are large, publicly-traded companies against which these startups are competing. Such public companies help investors estimate the price at which they may be able to sell shares in the startup in the hoped-for IPO.

It offers a product that customers love . Investors will talk with your current customers to assess how enthusiastic they are about your startup’s product, how likely they are to keep buying and using it, and whether they have unmet needs that they think your startup could satisfy.

Its executive team has prior success scaling to liquidity. Potential investors will also evaluate the strength of the startup’s executive team, specifically looking for each executive’s previous success in scaling a startup to liquidity as well as the CEO’s ability to motivate the executive team to collaborate in pursuit of rapid revenue growth.

Its business processes are sufficiently robust to enable the company to sustain high customer satisfaction as it grows. Investors also will investigate whether the startup has robust business processes. This means they will examine whether it can develop new products that customers want without taking too much time or costing too much, whether it can market and sell the product quickly, and whether it can provide after-sale service that satisfies customers and does not require too much time or cost. Moreover, investors will want assurances that the startup can perform these activities effectively and efficiently as the startup grows rapidly.

The cases that follow highlight successful and less successful handling of these investor requirements.

Success Case Study: Anaplan Sprints to a 2018 IPO

Introduction

Founded in 2006, San Francisco, California-based Anaplan, a cloud-based business planning service, had raised about $300 million in capital by July 2018 and under a new CEO was able to go public in October 2018, months before its 2019 IPO goal. Anaplan was taking customers from IBM, Oracle, and SAP in the $20 billion market for enterprise performance management. CEO Frank Calderoni said Anaplan “helps companies to make better decisions in response to change through connected planning. For example, [our cloud-based planning service lets] Revlon connect information about customer retail purchases with its supply chain so that Revlon can stock the right product in the right place at the right time.” Calderoni joined as CEO in January 2017. Before that he had spent 17 years as CFO, often paired with an operating role, at Cisco Systems and SanDisk. Most recently, he had been CFO and EVP of operations at Red Hat, an enterprise software company, where he spent less than two years.

Calderoni took over after its previous CEO, Frederic Laluyaux, who had previously been an executive at SAP, parted with the company in April 2016. Laluyaux spent over three years as CEO, having taken over in September 2012 from co-founder Guy Haddleton. Laluyaux raised $90 million in a Series E round of capital in January 2016, which valued Anaplan at $1.1 billion. But the board decided that the company would not be able to go public under Laluyaux’s leadership, After Laluyaux left, then-Chairman Bob Calderoni (Frank’s brother) said, “The board and Fred believe it’s the right time to bring in a new set of talent to take us to a much higher level and become a much bigger company.” Ravi Mohan, Anaplan board member and managing director at Shasta Ventures, said, “Unbridled growth [is no longer] the most valued characteristic. Now, it’s profitable sustained growth, and we’re building a company that reflects that.”

Case Scenario

When he took over as CEO, Anaplan, which made money by selling monthly subscriptions, was large enough to go public and was still growing fast. As Calderoni pointed out, “In its fiscal year ending January 2017, Anaplan had $120 million in revenue, was growing at 75%, added 250 customers for a total of 700, employed over 700 people in 16 offices in 12 countries, had raised a total of $240 million in capital, and generated good cash flow.” Anaplan believed that customers preferred its service to those from IBM (such as Cognos) or Oracle (Hyperion) because these products did not help companies respond as quickly to change. Calderoni said, “Customers are moving away from the spreadsheet model that compares actual results to plan. They want what we offer, which is to make it easy to connect large numbers of users to each other and to make decisions with the help of ‘what if’ analyses; for example, to help them set prices by estimating sales under different price scenarios.”

By April 2018, the company had grown to over 1,000 employees and was getting ready for an IPO. As Calderoni explained, “In the early stage, you are in a trial customer situation where you hope to get 5 or 10 early adopter customers who see your product’s benefits. In the middle stage, you are going to market, building on your proof points; you are setting revenue, growth, and customer acquisition objectives. In the late stage, you take your success, say, in three domestic vertical markets and expand globally. At this stage, where we are now, we want to sustain and repeat growth predictably so we can become a public company.”

In December 2017, Calderoni raised a $60 million Series F round of funding which valued Anaplan at $1.3 billion. And in a July 2018 interview, he described how Anaplan’s five rounds of capital raising fit within the three scaling stages. “Our January 2010 Series A and January 2012 Series B rounds raised $5 million and $11 million, respectively. The A round went to product development and the B round was to expand the sales force and win early adopter customers. At that point we had completed Stage 1 and were on to Stage 2. Our April 2013 Series C ($33 million) and May 2014 Series D ($100 million) rounds went to building out our expansion plan. With the Series C and D funds, we started out in the UK and California and expanded in Europe and the U.S. By 2016, we had 40% of our revenue outside the U.S. and were moving into Stage 3. Our 2016 Series E and 2017 Series F rounds helped us build disciplined processes and are helping us to scale to an IPO. At the Series F round, investors were asking whether we had customers with whom we could land and expand and whether we had a path to cash flow breakeven. We must achieve this while adding to our global sales and customer service operations tailored to each country’s regulatory, language, and currency differences. We are also investing in developing partnerships with distribution channels and consultants to help us reach new customers. At the same time, we are becoming more efficient; we are articulating how we will lower our costs through better processes.” And on October 12, 2018, Anaplan went public, valuing the company at about $3 billion.

Case Analysis

To succeed at raising capital during the third stage of scaling, investors look for a company that is on a clear path to $100 million or more in revenues and is growing at least 40% annually. Depending on market conditions, investors may also expect a company to be profitable. More specifically, if investors are feeling flush with cash, they may be willing to provide Stage 3 capital to a company that is unprofitable but growing quickly to $100 million; however, if they are afraid of a market reversal, they may only invest at this stage if they are convinced that the company is or can become profitable by the time it reaches $100 million in revenue.

Set and achieve ambitious quarterly targets for revenue and customer growth.

Build a team of top executives that has prior experience taking companies public and sustaining their growth.

Assure that systems and processes for running a public company are in place and have been tested.

Have a clear roadmap for sustaining rapid growth for at least three years into the future.

Measure costs and customer satisfaction, and redesign the organization and key processes to assure that costs will drop and customer satisfaction will remain high as the company scales to an IPO.

Less Successful Case Study: SentinelOne Is Not IPO-Ready As It Grows to $100 Million

Introduction

In April 2018, Palo Alto, California-based anti-virus software provider SentinelOne expected to win $100 million in revenue from its rivals in 2019 but with $110 million in capital did not see itself as being ready for an IPO, probably due to the challenge of standing out from many competitors. SentinelOne, which was founded in 2013, said its endpoint security product was “a uniquely integrated platform that combined behavioral-based detection, advanced mitigation, and forensics to stop threats in real-time. Specializing in attacks that utilize sophisticated evasion techniques, SentinelOne was the only vendor who offered complete protection against malware, exploit, and insider-based attacks.” SentinelOne’s cofounder and CEO, Tomer Weingarten, was “responsible for the company’s direction, products, and services strategy. Before SentinelOne, Weingarten led product development and strategy for the Toluna Group as a VP of Products. Prior to that he held several application security and consulting roles at various enterprises and was CTO at Carambola Media.”

Case Scenario

At 300%, SentinelOne was growing faster than its industry—2018 endpoint security industry revenues of $11 billion were expected to grow at a 12.7% rate to $20 billion by 2023—and had raised $110 million to fund its growth, much of which came at the expense of incumbents. What’s more, SentinelOne expected that in 2019 the revenue it would take from incumbents would total $100 million, which is typically sufficient for a fast-growing company to go public. The good news about SentinelOne was that its product received high marks for effectiveness and low price. According to an April 17, 2018 NSS Labs report, “Advanced Endpoint Protection Comparative Report,” SentinelOne was recommended with a 97.7% security effectiveness score and a total cost of ownership per protected node of $148, which is 51% below the average TCO/node of $301 for the 11 recommended products covered in the report. Perhaps this strong relationship between effectiveness and price contributed to SentinelOne’s growth. As Weingarten explained in an April 2018 interview, “We are growing bookings at 300%. 70% of them are complete rip and replace from McAfee and Symantec. Pandora replaced Symantec with SentinelOne. We win 70% of the time we compete in a proof of concept. We expect a displacement book of $100 million in 2019.”

SentinelOne succeeded in raising $110 million over four rounds between 2013 and 2017, the largest of which was used to fuel aggressive marketing and sales expansion. SentinelOne was not preparing for an IPO. SentinelOne’s seed rounds in March 2013 ($20,000) and August 2013 ($2.5 million led by Granite Hill Capital) were to be used to transition from beta to launch by September 2013 and to hire its initial workforce and sales force in the United States, according to Weingarten. It raised a $12 million Series A round in April 2014 led by Tiger Global Management and a $25 million Series B in October 2015 led by Third Point Ventures that valued the company at $98.2 million. The Series B was intended to scale sales and marketing and to add features to its platform, according to Weingarten, increasing the company’s headcount from 50 to an estimated 120 by the middle of 2016. In January 2017, SentinelOne raised a $70 million Series C round in led by Redpoint to aggressively expand its sales and marketing efforts. At the time of the Series C closing, Redpoint partner Tom Dyal, who joined SentinelOne’s board, was excited about the size of its market and its recent customer wins and distribution partnership, As he said, “Endpoint security [was] a $10 billion market opportunity as businesses migrate away from traditional anti-virus software. SentinelOne customers include Time and it [had] recently signed a North American distribution deal with Avnet.”

Nevertheless, by April 2018 SentinelOne seemed to be growing rapidly but making organizational adjustments that suggested not all its operations were in shape for an IPO. According to Weingarten, “Between 2016 and 2017, we boosted new customer bookings 300%, increased our customer base 370% to 2,500, and added to our employee headcount by 175% to over 300.” This growth was remarkable considering the organizational churn it suffered, which hurt Sentinel One’s execution and vision. According to the January 2018 Gartner “Magic Quadrant for Endpoint Protection” report, SentinelOne’s biggest 2017 challenge was “churn in staff roles across product, sales, marketing, and other internal and client-facing groups. Gartner clients reported inconsistent interactions with SentinelOne throughout the year.” SentinelOne viewed this turmoil as an investment with a positive return. “2017 was a year of significant change and development for SentinelOne. The company up-leveled its leadership team to take the product and go-to market to new heights. These leadership changes are exactly what has created the unprecedented results we’re currently experiencing, and in record time! Key was the hire of Nicholas Warner, Chief Revenue Officer, who led Cylance’s global sales growth,” said Weingarten.

Unfortunately for SentinelOne’s investors, by January 2018 there appeared to be too many cybersecurity companies competing for a spot in a very small IPO window. Too many startups could not keep growing as technology changed. David Cowan, a partner at Bessemer Venture Partners, said “I have never seen such a fast-growing market with so many companies on the losing side.” With so many vendors, investors were deciding to concentrate on just a few, which left the remaining companies stranded. Dave DeWalt, the former CEO of cyber security company FireEye, said, “Suddenly, we are in this situation where there are just too many vendors and too few can be sustained. You’re starting to see companies go, ‘Oh my gosh, what do I do? Can I get more capital? Do I have to merge?’” Meanwhile, unsuccessful IPOs in the sector seemed to have scared investors. A case was ForeScout Technologies, a provider of software that helped companies keep the devices of their employees secure, which raised $116 million in an IPO in October 2017 that valued the company at about $800 million, down from its $1 billion valuation in the private markets a year earlier. ForeScout’s backers, including Intel Capital and Accel Partners, had to moderate their valuation expectations for the IPO to be successful. (By July 20, 2018, it was trading at a $1.5 billion market capitalization.) “Some have compared some cyber security companies to cockroaches,” DeWalt said. “They can’t die, but they aren’t smoking hot either.”

Case Analysis

SentinelOne’s efforts to raise capital for the third stage of scaling appear less successful than Anaplan’s. SentinelOne appears to be growing very rapidly, citing very high rates of growth in the number of customers and employees. Moreover, if the company indeed can gain $100 million in revenue by taking business from rivals, it should be able to go public with such high growth. On the other hand, the intensity of the rivalry in the industry, the rise in venture capital skepticism about being able to earn a high return on investment in the endpoint security market, and the organizational churn at SentinelOne seem to mitigate against hopes for a positive outcome for the company. In the absence of audited financial statements, it is impossible to discern whether the company needs a new round of funding to keep growing; however, unless the company is profitable, there is a good chance it will need to raise even more money to reach the level needed to go public.

Principles

- Do

Aim at large markets.

Generate rapid revenue and customer growth that motivates venture capital firms to ask to invest in the company.

Have a clear path to reducing costs for designing, selling, and servicing products and boosting the value of the product to current and potential customers as the company grows.

Hire an executive team with prior experience taking a company public and continuing its growth after the IPO.

- Don’t

Assume that capital providers will keep funding a growing company that has no plan to become profitable.

Shield your current executive team from pressures to adapt to the needs of Stage 3 scaling.

Target a small market and fail to shift focus in response to changing investor sentiment.

Stage 4: Running the Marathon

It is very rare that a founder can turn an idea into a public company and keep the company growing after the IPO to become a leader in a very large market. My conversations with hundreds of entrepreneurs suggest that virtually none of them will publicly acknowledge that the IPO is an important event in the company’s development. Most often they refer to the IPO as a minor funding event that should not interrupt the company’s inexorable march to becoming a company that grows so influential that it will change the world. Not surprisingly, given that only a handful of founders have achieved this, most founders who take their company public lack the skills needed to keep running their companies following their IPO until they surpass, say, $10 billion in annual revenues while growing at over 20% a year.

Cash flow from operations: Profits are always the lowest-cost source of capital. If a company is generating enormous amounts of cash flow from its operations, it can simply use that money to fund its investments in future growth.

Higher share price : The key to success is taking actions that propel the company’s stock price upward. That’s because one of the easiest ways for a public company to raise more capital is to sell stock. And the higher the stock price, the more capital can be raised at minimum dilution to existing shareholders.

Borrow money : If a company generates high cash flows, they will provide ample comfort for bankers or bond-holders should the company decide that borrowing money is a better way to raise funds for future growth because it does not require diluting existing shareholders.

Beat and raise : Every quarter investors await the company’s financial report and its forecast for the next quarter. If the reported results and forecasts for measures such as revenue growth, profit growth, and number of customers exceed investors’ expectations, the stock price will rise. If investors are disappointed, the stock will fall. For a CEO to beat and raise each quarter, the company must be able to set ambitious goals, make sure that the right people oversee achieving those goals and have the resources they need, and monitor progress during the quarter to make any needed adjustments. Of course, even the best founder-led companies miss quarters occasionally. But if such CEOs can beat and raise in most quarters, investors are more likely to view such misses as a buying opportunity.

- Invest in growth : To keep beating and raising, CEOs must also take a longer-term view of their company’s growth opportunities. Specifically, CEOs must try to make the most of the company’s current sources of growth from among the five dimensions of growth I discussed in Chapter 2, but recognize that these sources of growth will become saturated. Such saturation means that unless the company invests in new and accelerating growth vectors, the company’s overall growth will stagnate. Investing in the right growth opportunities, which could include selling current products into new geographies, acquiring new products, or building new products to sell to current and new customers, is an essential skill that few CEOs can master. Envisioning such opportunities requires creativity, vision, and a deep understanding of how customer needs, technology, and competitor strategies are evolving. But investing in the right growth opportunities hinges on affirmative answers to five questions:

Is the market opportunity large and growing rapidly?

Do we have the capabilities needed to build and sell a product that leads in that market?

If not, can we acquire those capabilities and integrate them effectively?

Do we, or can we obtain, the capital needed to fund the growth investment?

Can we communicate to investors our goals and progress in capturing the growth opportunity?

Success Case Study: Talend Goes Public and Its Stock Soars

Introduction

Redwood City, California-based data cleaning service Talend went public in 2016, 11 years after it was founded, and in the nearly two years thereafter its stock rose 146%. Talend provided open source software with a “wrapper” that cleaned data so companies could analyze it to make decisions. Its software platform, “Data Fabric, integrates data and applications in real time across modern big data and cloud environments as well as traditional systems,” according to the company. Talend, which targeted the $2.7 billion (2016 revenue) data integration tools market, made money by selling subscriptions to software that cleaned up data errors. “We help companies get value from data used to make decisions. We work on the first mile in the data analysis process, which is to fix errors in the data before companies analyze it. Every customer’s biggest problem is data quality. Our product is a combination of open source software and a wrapper that is sold by subscription,” said CEO Mike Tuchen in a July 2018 interview. Talend was founded in 2005 but Tuchen signed on as CEO in January 2014 as the company was raising a round of funds. He came to the company with a strong background in the software industry but had never taken a company public or been CEO of one thereafter. He had previously been CEO from May 2008 to October 2012 of security data and analytics provider Rapid7; was General Manager of SQL Server Marketing at Microsoft; and had a nice string of degrees: a B.S. from Brown and M.S. from Stanford (both in Electrical Engineering) and an M.B.A. from Harvard.

Case Scenario

Talend enjoyed rapid revenue growth while reporting net losses and fluctuating free cash flow. Since 2013, its revenues had grown at a 29.5% compound annual rate to $148.6 million in 2017; its net loss increased from about -$20 million to -$31 million, and its free cash flow was negative in each of those years except 2016 when it was about +$2 million, according to Morningstar. Talend’s 2018 unit economics looked good. According to a June 2018 investor presentation, in the first quarter of 2018, the company enjoyed over 100% cloud and big data growth; 121% net expansion, a measure of its ability to sell more to existing customers; 85% subscription revenue; and $5 million in positive free cash flow. Talend expected rapid growth in 2018. “When I joined the board in 2013, we had about 300 people and now we have 1,000. Our revenue was about $50 million in 2013 and we expect $203 million in 2018 revenue this year [which is 36.6% more than 2017 revenue],” Tuchen explained.

Under Tuchen’s leadership, Talend prepared itself to be a public company, in part by changing who it sold to and how it sold. As he said, “In 2013, we sold to mid-market companies and lower enterprise customers. But the market was confused about the company. 72% of our customers stayed with us each year and we had no clear advantage in our position. We needed to be more efficient about how we sold. We changed the team, the strategy, and the way we set and hit goals.” The changes Tuchen made worked, resulting in a 73% increase in sales productivity. “We changed our strategy from being a low-end disrupter to a next generation leader. Due to rapid changes such as the move to the cloud and the use of data lakes [a storage repository that holds raw data in its native format until it is needed] we had an opportunity to be a leader. We targeted early adopters in financial services, retail, high technology, and manufacturing (companies using sensor data). We improved the way we described our product benefits and the way we hired and trained our sales people. Since they were meeting their goals right away, our attrition rate dropped,” according to Tuchen.

While Tuchen was figuring out how to fix these problems, he was also thrown into the middle of a major funding effort, raising $20 million in capital and retiring $20 million in debt, with hopes of going public thereafter. Investors ask different questions as a startup goes from Series A funding to later rounds, according to Tuchen. Before a Series A, they want to know what problem the company is trying to solve, the size of the market opportunity, why the company’s solution will win, and whether the team can build a solution. In Series B, investors care about early customer traction, revenue, and repeatability. And in Series C, they want to see that you are getting the unit economics in line. When Tuchen was trying to close the pre-IPO round of funding, he was in a hurry. “We started in October 2013 and closed in December. Investors asked us how we would get our unit economics in line. We wanted to improve sales productivity but did not have all the details.”

Tuchen also shed light on Talend’s IPO process . As he said, “We started six months before the IPO with our pre-IPO road show, getting feedback on our presentation. Two weeks before the IPO, we went out on a corporate jet to visit with potential investors. Now that we are public, the marathon is just starting. I spend 20% of my time involved with externally-facing activities like investor meetings and earnings calls.” Talend has not needed to raise money since the IPO. “With the exception of a $10 million acquisition, we have not touched the $109 million we raised in the IPO because we were cash flow positive when we did the IPO. We have done three follow-ons in which investors sold shares. I spent a couple of hours with lawyers; within two hours of the market close, two or three investors cashed out their stakes. One of our venture investors paid back its entire fund from those proceeds.”

Tuchen was focused on the short- and long-term future of Talend. “You can’t just beat-and-raise each quarter. We set a three-year goal and do detailed planning for the year ahead. If we are doing well each quarter, it is progress on a multi-year journey.” In May 2018, Tuchen sounded optimistic after reporting its first quarter results. As he said, “Our solid financial results were driven by strong subscription revenue growth of 44% and continued success with large enterprise customers. We anticipate our cloud momentum will continue as we roll out our new cloud product roadmap in 2018 and collaborate more closely with leading cloud partners.”

Case Analysis

Make the business model scalable before going public.

Create structured processes that enable the company to set and achieve realistic yet ambitious goals for future growth.

Plan three years into the future and make everyone accountable for achieving quarterly goals in the first year of the plan.

Less Successful Case Study: Domo Raises $690 Million and Loses 78% of Its Value in Its June 2018 IPO

Introduction

American Fork, Utah-based Domo designed and delivered an executive management platform as a service to help executives manage their business. It was founded in December 2011, went public in June 2018 at a 78% discount to its most recent private valuation, and a month later its shares had lost 32% of their value. Domo had 796 employees and 1,500 customers in industries such as financial services, professional services, technology, energy, consumer goods, manufacturing, healthcare, media, retail, and transportation. Its clients included small organizations to large enterprises, including 36% of the 2017 Fortune 50. IDC estimated that Domo’s target market of business intelligence software would reach $24.4 billion in 2018. Founder and CEO Josh James, who controlled 86.1% of Domo’s voting stock and owned 3,263,659 of its Class A shares, cofounded and was CEO of marketing services firm Omniture from 1996 to 2009, which went public in June 2006 and was acquired in September 2009 for $1.8 billion, a 24% premium to its pre-deal value, by Adobe Systems. James studied entrepreneurship at Brigham Young University for three years before dropping out.

Case Scenario

While Domo grew, its business model was unprofitable. For example, its 2018 revenue grew 32% to $108.5 million from the year before while it lost money in both years, but its 2018 loss of $176 million was 5% below its 2017 net loss. The basic version of its product was available for free for a year and allowed five users access to analyze up to five million rows of data. After a year, the users were required to choose from three pricing tiers “ranging from $83 per user per month to $190 per user per month. The highest tier subscription came with features such as the ability to analyze up to two billion rows of data, advanced governance and security, HIPAA compliance capability, consulting from certified partners, and premium support.”

Domo failed to scale its business model before going public. Between January 2017 and April 2018, Domo went from no debt to $96.1 million as it burned through nearly $150 million in cash a year from its operations in both years. Indeed, without the proceeds of its IPO, Domo did not expect to be able to meet its expected cash needs. According to its June 2018 prospectus, as of April 2018, its roughly $72 million in cash coupled with a tapped-out line of credit would only be enough money to cover its operating obligations for the year ending April 2019 unless Domo was able to raise money in an IPO. Without the IPO, Domo said it would seek other forms of financing and absent “other equity or debt financing by August 2018, management [would slash] operating expenses, [including] significant reductions to marketing costs, including reducing the size and scope of our annual user conference, lowering hiring goals, and reducing or eliminating certain discretionary spending as necessary.”

Domo raised 11 rounds of financing totaling nearly $690 million but compared to other venture-based startups generated relatively little annual recurring revenue. Indeed, Domo’s valuation at the time of its $125 million Series C round was $825 million, a figure that soared to $2 billion when Domo raised its $200 million Series D round in 2015 and inched up to $2.3 billion at the time of its $100 million Series E round in 2017. Pre-IPO investors took a huge loss since Domo’s June 28, 2018 IPO, which raised $193 million, valued Domo at $500 million, or 22% of its peak private market valuation. According to the so-called hype ratio, defined as the amount of venture capital invested in the company divided by its annual recurring revenue, Domo was a very highly hyped company. Other SaaS companies generated far lower hype ratios. Adaptive Insights, which raised $175 million and generated $106 million in revenue, had a ratio of 1.6 and Zuora, with $250 million in capital and $138 million in annual recurring revenue, had a ratio of 1.8. Domo, with a hype ratio of 6.4, topped them all. As technology executive Dave Kellogg wrote, “It’s one of the most hyped companies I’ve ever seen.”

James was optimistic about Domo’s future , viewing the IPO as the best way to raise money to help achieve his vision. As he said on the day of the company’s IPO, “We’re hitting all the right metrics in terms of finally proving the enterprise. Now we have to go and execute.” Domo went public to avoid getting “stuck on a bridge to nowhere, or in the middle of the desert, when something like that happens.” Domo claimed to have 400 CEOs as users, thus making it different than rivals. He viewed Domo’s high marketing and R&D costs as a positive investment in its future. He had no intention, for example, of stopping its Domopalooza conference, which had included celebrities such as Alec Baldwin, Nelly, and Kesha. James blamed Domo’s change from targeting small businesses to big-company CEOs as the source of its afflictions in early years in the wake of the high turnover among smaller customers. Echoing Theranos ex-CEO Elizabeth Holmes’s October 2015 CNBC interview, James said, “People have taken pot shots, people have questioned our product. When you’re innovating and doing something that no one’s done before, you are going to have a lot of doubters. That’s why no one has done it.”

Case Analysis

James used his success with Omniture to insulate the company from scrutiny while raising capital.

Domo spent too heavily on marketing and research, and assumed that investors would keep investing more to cover their losses.

Domo raised too much capital before hurdling the second stage of scaling.

Dome overconcentrated control in the CEO’s hands.

Principles

- Do

Try to generate sufficient operating cash flow to finance growth.

Beat expectations and raise guidance consistently each quarter.

Invest, after careful research, in new growth opportunities that can sustain rapid growth.

- Don’t

Go public before building a scalable business model.

Demand total control of the board.

Expect investors to fund post-IPO operating losses.

Capital Raising Success and Failure Principles

Summary of capital raising principles

Scaling Stage | Dos | Don’ts |

|---|---|---|

1:Winning the first customer | If you are a first-time founder, try to raise capital from friends, family, crowdfunding, and business plan competitions. Use the funds to improve product so initial design partners will become enthusiastic customers. | If you are a first-time founder, don’t try to raise capital from venture capitalists or angel investors, unless you have strong personal connections to them. Work on product in isolation from potential customers. |

2: Scaling the business model | Look for venture capitalists who have industry expertise and knowledge of how to scale. Make sure you have at least 10 customers who are willing to recommend your company to others. Target a large market. Field an executive team of functional leaders who have enjoyed previous scaling success. Set and exceed growth targets. Redesign business processes to lower cost and boost customer retention | Try to raise capital for scaling before your business model is efficient. Focus on revenue growth at any cost. Field a team of executives who lack experience scaling. Attempt to raise capital without customers who are willing to serve as enthusiastic references. Focus on a market that is too small. |

3: Sprinting to liquidity | Set and exceed aggressive quarterly revenue, customer count, and cash flow goals. Hire a team with experience taking a company public. Enhance sales, marketing, service, and product development processes to lower costs. | Raise capital for a business that consumes much more capital than it can generate. |

4: Running the marathon | Beat revenue, profit, and customer count goals each quarter and raise guidance. Identify and invest in future growth opportunities with attractive markets in which the company can become a leading player. Plan for the long-term and make people accountable for the first year of the plan. | Grow revenues without controlling costs. Assume that investors will continue to finance operating losses. |

Are You Doing Enough to Raise Capital at Each Scaling Stage?

Do you have or are you creating customers who will happily refer you to others?

Is your product targeting very large markets?

Can your company offer so much value to customers that it will gain significant market share?

Do you have a team of experienced executives with prior experience taking a company public?

Does your company have the discipline to set and exceed ambitious quarterly goals for growth and profitability?

Conclusion

Raising the capital needed to fund growth is much easier if your company has or can build a reputation for creating value for customers and operating a business model that becomes more efficient as your company grows. If your company can set and exceed ambitious goals for revenue and customer growth paired with improving cash flow, investors will ask to invest in your company. When CEOs generate such inbound investor interest, they are more likely to be able to select investors who share their vision, can help the company achieve that vision through capital and advice, and are willing to accept a reasonable valuation of the company as they invest. A critical element of achieving and sustaining growth is creating culture, which we’ll explore in Chapter 4.