Chapter 2. Nontechnical Influences

Why does one pen get thrown in the garbage after use, another is worthy of a refill cartridge, another becomes a family heirloom, and another resides in a museum? Ancient philosophers asserted the three motivators of all human inquiry are pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness. This triumvirate of cognition, aesthetics, and morality offers a framework for looking at design as an attempt to develop functional products and systems, express cultural heritage, and express an aesthetic quality. The first category can be referred to as mechanistic influences. The other categories can be referred to as nonmechanistic (a fancy name for nontechnical) influences such as aesthetics, brand management, and material culture. These nonmechanistic influences can be determined by delving into the social sciences, perhaps most appropriately ethnography, which is the study of human culture.

The Role of Aesthetics in Design

The philosophy of aesthetics is connected with value judgments and is a preeminent concern for industrial designers. Even in a study of engineering principles, this subject cannot be ignored. The mark of a professional designer is integrating aesthetics into everything. Often beauty is subordinated to other concerns such as functionality and brand management, but making a design appealing and intuitive is part of the aesthetic treatment. These are key added values provided by the designer.

Aesthetic can be defined as “pleasing in appearance,” and while an important design consideration, this quality is subjective and defies quantification. While three-dimensional forms consider traditional elements of design such as symmetry, repetition, rhythm, balance, proportion, harmony, movement, color, and texture, a broader aesthetic assessment can be informed by all the sensory inputs: sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. The interplays between these senses are complicated; for example, the visual appearance of a perfume bottle is often as important as the smell, while the thickness, shape, crunch (biting pressure), and color of a potato chip influence the consumer experience beyond smell and taste.

The foundation under which aesthetics are evaluated is a contested issue among philosophers. One philosophical school (aestheticism) believes aesthetic evaluation is independent of other judgments, while others, such as the instrumentalists, believe aesthetic value is connected to function.

A synonym for aesthetics could be appeal. Making a design appealing to the senses has allure. Allure is why all cultures seem to surround themselves with appealing things from nature, whether attractive stones or flamboyant feathers. You might not think of a Hummer as a pretty car but it is appealing in its own way. The same is true with an aircraft carrier or Parisian coffee shop. They have appeal beyond the visual.

The aircraft carrier in Figure 2-1 is probably not considered beautiful—its appeal lies in its capabilities, which are reflected in the ship design. The watch in Figure 2-2 is a rather busy collection of round and linear shapes, yet it has an appeal with its technical proclamation.

Figure 2-1. While violating all visual design principles, aircraft carriers have a peculiarly provocative visual appeal

Figure 2-2. Complexity can be appealing, as in the case of this watch

A discussion of aesthetics should consider the notion of beauty. Art is often created so its beauty is proffered to human regard. The Austrian-Swiss poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s poems speak of beauty making the inanimate alive, where an ancient torso of Apollo “would burst out of its confines and radiate like a star” much like the Jaguar E-Type sports car. Human beauty has its effect: from Helen of Troy’s face “launching a thousand ships” seeking to rescue her from Troy to the political intrigue caused by Cleopatra and Antony. The mythological three graces of beauty, charm, and joy (Figure 2-3) entertained the guests of the gods while the poetry of Sappho and Dante drool with notions of beauty and passion. Beauty can evoke protectiveness—you kill a cockroach, but not a butterfly. Beauty is a force to be dealt with, although it is less charged when considering nonsentient objects.

Figure 2-3. Detail of the Three Graces from Botticelli’s Primavera

We drive out of our way to see a beautiful vista or to catch eyes with a charming dog on a porch. We carry things of beauty with us, and like crows, seem to like shiny things that leap out. We often like small things we can wear or hold. Jewelry, watches, wallets, clothes, shoes, and personal electronics are staples of the consumer market. We leave the big stuff to the state to maintain in museums.

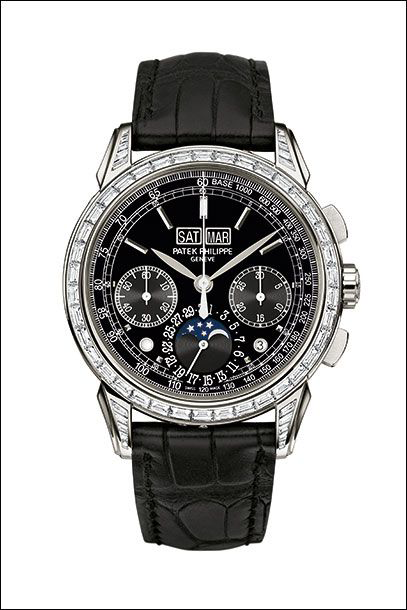

Beauty has a historical component and our notion of beauty changes. Time makes human beauty rise and fade from baby to the gruesome corpse. In the same fashion, an object’s allure also changes with time. Byzantine paintings may have lost their beauty, but are preserved to maintain a connection with our past. Will Pollock’s drip paintings be attractive in 1,000 years? The notion of beauty in the fine arts changes century to century, as illustrated in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4. These paintings show the changing appearance of contemporary beauty from Byzantine to Renaissance to Abstract

Observing a three-dimensional object has a time component like a cartoon strip. We see different things as we move with respect to the object. This movement shows us new vistas and even surprises like what we might encounter during a walk in the woods. Design that reveals new features, functions, and forms can be equally intriguing.

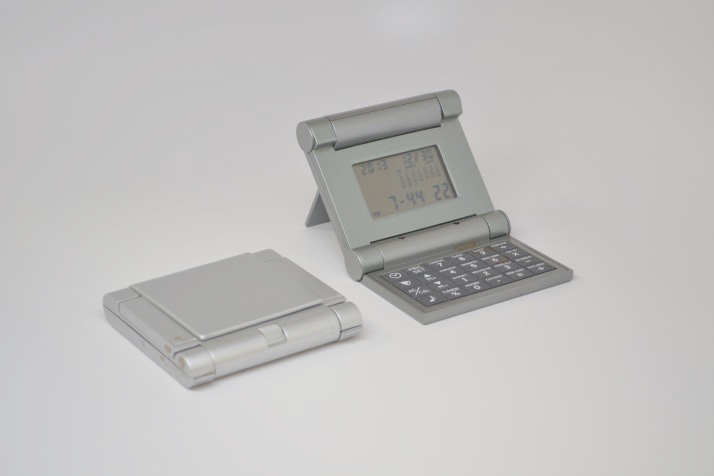

Some designs are appealing for unique reasons. For example, the sculpture in Figure 2-5 fits nicely into a hand and that has its own appeal. The electronic calendar in Figure 2-6 unfolds automatically—an intriguing and surprising dynamic.

Figure 2-5. Part of this sculpture’s appeal is that it feels nice in the hand

Figure 2-6. Watching this calculator unfold is appealing

It is important to note that pretty two-dimensional renderings are not design. Software has allowed us to make a cheese slicer or a lawn mower look like a gleaming pearl with diamond accents. Dramatic portrayals of ideation can show the progression from a cube to an elegant toaster. Software can then make the toaster look like it went to the best beauty parlor in Palm Springs. But is it a good design? Is it appealing in its real “I need to make toast at 6 a.m." context?

There is a difference between the fine arts and design. Fine arts are self-expression, while design is purposeful art that needs to be informed by all the stakeholders and especially the end user. Consequently, when designing for others, aesthetics takes on a tricky character and must be developed not only by the designer’s creative senses and style orthodoxy but also by cultural issues that may be best approached ethnographically.

The black utility knife in the background of Figure 2-7 has an inner beauty. It has been carefully designed so that the user can easily open it and change blades. The new blade holder rotates up and makes the whole process pleasant. The red utility knife in foreground requires a screwdriver, patience, and a spare screw after the original one rolls off the workbench and becomes lost.

The Need for Brand Management

Design is not self-expression; rather, it synthesizes a variety of market requirements. One of these requirements is brand management. Designs often need to perpetuate hard-earned brand appeal. The transcendent appeal of branded products is carefully managed and jealously guarded.

As products moved from the local artisan, branding emerged from the marketplace largely to confirm legal protection and guarantee quality as well as homogeneity of product or experience. Branding allows for market control and rapid introduction of new products or features. I remember traveling in India many years ago and buying a boxed set of cookies. Usually goods were not packaged in any fashion and I was eager to enjoy the yummy cookies that the photographs on the box promised. I soon found out that the cookies pictured on the package did not represent what was inside. I was so conditioned to truthfulness in presentation that I didn’t think of this possibility. I can’t remember the brand but I remember the experience!

Brands add value to a product. This brand equity is an example of customer-perceived value and is worth real money. We don’t buy clothes to keep us warm or a car to simply allow us to travel between points. The added values fall into the categories of experience, effectiveness, visual appearance, and social associations.

Brand experience reflects the personality of the brand, such as the comforts associated with Betty Crocker or Birkenstock. The effectiveness of the brand relates to product superiority, whether it is the driving experience of a BMW or the curative powers of proprietary drugs. The visual appearance of labeling can be powerful. Imagine selling unbranded bottled waters and juices at the prices proffered now? Trendy drinks and delicate perfumes live off packaging.

The people associated with a brand are perhaps the leading connection into what is now known as a lifestyle brand. The brand we select represents both our individual and group identity. We value and defend our group/brand. This people association feeds right into natural group dynamics.

Sociological identity theories describing the relationship between an individual and a group are built upon the individual’s value for self. Individuals become group members who then need to protect the positive image of their group to satisfy the self-esteem they derived from the group. As a result, they regard other groups as inferior to their group. Group members with strong group identification attributed successful endeavors to the group members and negative group outcomes to external factors. Those who identified weakly with a group were more inclined to attribute negative group outcomes to group members and positive group outcomes to external factors. Myths and stories can also perpetuate a group identity.

To move design beyond individual connoisseurship, you need to consider the following in connection with brand management:

-

Themes associated with brand. You could consider action words or moods that are evoked by this brand. Use data (ethnographic and otherwise), not your own personal opinions.

-

Verbal associations with brand (e.g., tag line).

-

Graphic associations with brand (e.g., logo and colors). How does your design visually connect with the brand?

-

Does your design support the brand? Think in terms of:

-

Experience

-

Effectiveness

-

Visual appearance

-

People associations

-

Material Culture: The Context of Design

Is the Mona Lisa really a beautiful painting? Do we fly to Paris, wait in queues at the Louvre, and then take a picture of the painting through its bulletproof glass structure because we want to cherish the image, or are we more interested in telling our friends about our visit? Perhaps we are trying to connect with others through a communal experience. Perhaps we are trying to connect with an important time in human history or with Leonardo da Vinci himself.

The relationship between the individual, society, and history is considered in the concept of material culture. People understand material objects as they have been learned from their culture and we are compelled to understand the relationship between material objects and meaning. Individuals and groups attribute powerful significance to their history and strive to preserve it. A resistance to design change can derive from the dissonance between the identified cultural heritage and a proposed design change. This resistance can also be understood by considering the power of group identity in preserving the vital definition of a group upon which the individual derives identity. We often critique these designs as being too “something”—trendy, old looking, urban, country, ethnic, commercial, and so on. Design can derive from filial piety, where we identify with our ancestors and honor them by incorporating elements they value into design.

While traditional knowledge can be thought of as taking the past and applying it to the future, material culture motivates people to look at the present and relate it to the past, much like ethnography can inform anthropology and anatomy can guide paleontology.

A sense for material culture can be derived from gaining insights into the culture’s history and how the design application you are investigating is typically used. Think about special requirements, such as an oven being oversized to accommodate a Thanksgiving turkey or a refrigerator sized to accommodate a minivan full of food from a supermarket as opposed to a small grocery store. Consider how the product is disposed; does it become an heirloom or garbage? Does the product show up in family photographs and other memorabilia? Do people normally put their name or distinguishing marks on the product? Do people proudly show off the product to others? Is this product suitable for a gift to commemorate a special occasion, such as a wedding? Finally, a designer reflects on how his or her design aligns or offends the material culture.

The Influence of Tradition

Tradition reminds of us of the reliable comforts of home and hearth. We think of traditional knowledge as being refined by time to become an important standard for comparison, from the ingredients in our favorite food, to the tonal structure of music, to the shape of a chair. Traditional or indigenous knowledge is defined by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) as “the knowledge that an indigenous (local) community accumulates over generations of living in a particular environment. This definition encompasses all forms of knowledge—technologies, know-how skills, practice, and beliefs—that enable the community to achieve stable livelihoods in their environment.” Tradition represents one way of doing things or one way of understanding what has been successful in a particular cultural and technological context, providing the underpinning for designs such as used with houses, tools, furniture, and clothing. Traditions are valuable in many respects because they reduce mistakes and reinforce material culture.

Problems with Tradition

Some traditions are deeply embedded in the contours of society, such as road widths or legal systems, while others are new and potentially frustrating, such as increasing reliance upon remote controls, small display screens, or automated telephone systems. Traditional knowledge often supports nonmechanistic requirements such as belief systems, relationship to nature, and aesthetics. However, traditional behavior can be in conflict with normally powerful nonmechanistic forces. Anthropological studies show deforestation, fishing by water poisoning, hunting by large-scale forest burns, burning caches of food for social prestige, or even taunting children into touching fire and laughing at their pain occur even when these actions present some conflict with belief systems.

The problems associated with tradition can be seen in the design community where protective laws or tariffs are enacted or legal entanglements are erected. For example, the antiquated design of Harley-Davidson motorcycles was protected by US tariffs in 1983 and the entrenched automobile industry legally pursued the Tucker Car Corporation in 1949, resulting in part from Tucker’s nontraditional safety innovations that threatened the status quo. Within products themselves we see traditional design still giving us slotted screws (versus Phillips), undersized mug handles, excessively wide stovetops, and nonintuitive door operation.

Visual Stereotype: Familiarity Influencing Design

One subset of tradition that can be very helpful in design is the entrenched visual stereotypes we hold. Visual stereotypes are exemplars of form that provide a culturally relevant expectation of function. The visual stereotype helps users understand the product’s role. The identified visual stereotype represents an archetype upon which to start a design or as a baseline to compare a new design’s nonmechanistic appeal. This information is especially helpful when designing for a foreign culture or otherwise distinct community.

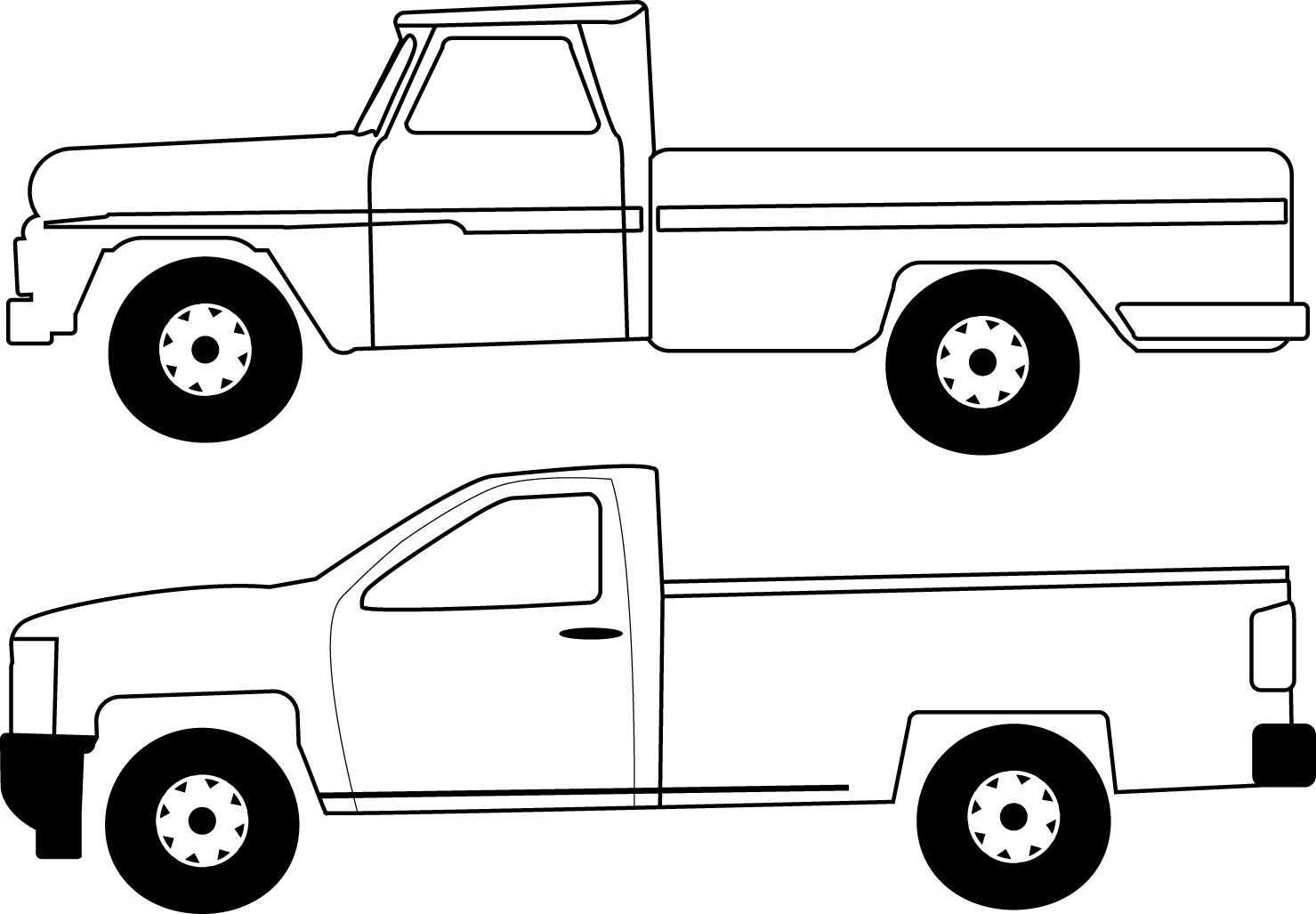

A good example of the power of visual stereotype is in American pickup trucks in which the proportions have remained unchanged for more than 40 years. This continued sense of proportion and visual stereotype is seen when comparing a 1965 and 2016 Ford pickup in Figure 2-8.

Figure 2-8. These visual stereotypes define a pickup truck

Deviations from the visual stereotype can be troubling because the purpose of the design can be unclear and its connection with a particular application (e.g., trucking) becomes confused. A designer must be aware of market expectations and artfully blend the expected form with new and exciting elements. This is much akin to poetry, in which a new language is not created, but rather exists as an established language used in surprising ways.

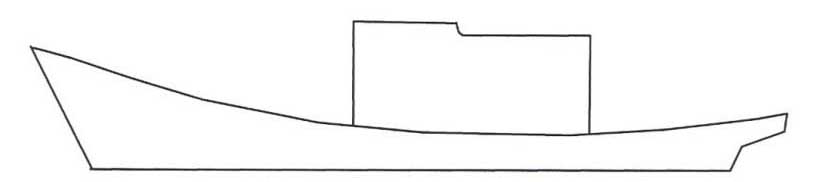

You can use visual stereotypes in practice by taking photographs of traditional designs and overlaying to find an expected visual stereotype that can provide a helpful starting point for design. For example, obtaining outlines of Malaysian trawlers like those shown in Figure 2-9 can produce the stereotypical profile shown in Figure 2-10. This profile gives us a starting point for design or a baseline upon which to compare design changes. This baseline is a helpful adjunct in ethnographic design.

Figure 2-9. Traditional Malaysian fishing boats

Figure 2-10. Visual stereotype of traditional Malaysian fishing boat

Ethnography’s Role in User-Centered Design

Ethnography is the study of human culture and strives to extract truths based on holistic and richly detailed subjective appraisals of small populations. Ethnography is an active form of research that requires the researcher to obtain data by observation or interviews while being able to respond to variables such as changing mood of the respondents, nonverbal behavioral cues, and sensitivity to ethical constraints. All the while, the ethnographer must be aware of this influence on respondents’ behavior and how it might skew results. Moreover, ethnography requires data triangulation and rigorous treatment of data in order to obtain valid conclusions.

Ethnographic design most commonly employs interviews and observation of potential users. These same techniques can also be applied to other stakeholders, such as retailers, repair services, and so on. Sometimes, potential users can give you information in creative ways. Figure 2-11 shows a Malaysian boat builder using clay to describe boat form and technical features.

Figure 2-11. Boat builder carving clay to communicate design details

Some of richest ethnographic data is derived from participant observation. This is where a trained ethnographer joins a group, and intimately knowing their social perspectives, observes how they interact with a design. However, focus groups and a variety of interviewing techniques are often used in industry, and they can provide a deep and focused insight into a design and its socially derived meaning.

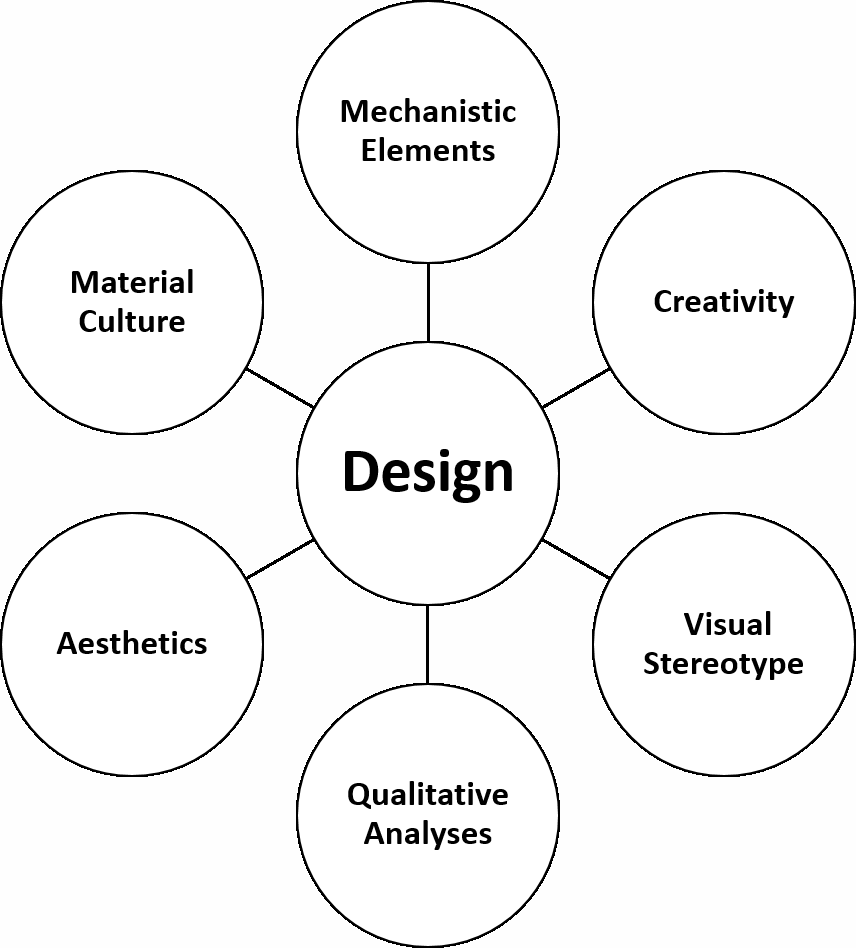

Ethnographically driven design has the advantage of broad application and allows a designer to work outside his or her culture to create effective designs. While it is unfair to ethnographers to say you can just read some books and go out and “do ethnography,” if ethnography is closed to designers, exclusionary barriers are raised that cripple both design and ethnography. The crippling is caused by failure to consider data that can only be approached ethnographically and depriving ethnography of practical application. We need to feed from a deep trough for our designs—physical sciences, life sciences, math, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and economics can all be tapped for methods that improve design. Designers need to borrow from all disciplines with alacrity and continually explore. Figure 2-12 offers a structure of culturally relevant design.

Figure 2-12. Designs derive from many inputs

Creativity: The Fount of Design

Because design is a practical application of creativity, it is worth a moment to consider some foundational aspects of this ability. Creativity is an abstract quality that can quietly aid our pedestrian problem-solving abilities or engorge our senses in artistic expressions. Creativity is most often recognized and honored in the arts and sciences, and a “creative person” is commonly associated with someone capable of producing art, literature, or scientific innovation. Creative expressions in other forms are not provided similar accolades. Therefore, we can’t discern between creative versus noncreative people in a universal sense, if that delineation even exists, by societal judgments. Shakespeare’s plays are still being performed, thereby reinforcing their relevance to contemporary Western society, whereas the game devised by some parent in a remote village disappears into the flow of time.

Investigating individual creativity may also have a disruptive effect on the process itself. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung noted “as long as we ourselves are caught up in the process of creation, we neither see nor understand; indeed we ought not to understand, for nothing is more injurious to immediate experience than cognition.” However, we can gain insight into individual and group motivations for acting creatively. These encouraging forces can best be considered by investigating different psychological and sociological theories for behavior.

While psychological theories describe individual motivations for creativity, our desire to act creatively is also influenced by social context. Groups can support or hinder creativity. Creativity can be part of a culture or dismissed as a distraction. The influence of groups upon creativity can be quite overt, as in the employment of scheduled brainstorming meetings, or the use of tangible rewards for creativity, such as money. However, the group forces can also be subtle. A group can view itself as being creative and therefore the individuals within the group also consider themselves creative. This self-identification is similar to the brand appeal arduously earned by sophisticated advertisers and is highly potent in directing individual behavior.

The best description of the nature of creativity lies in a mix of psychological and sociological theories that attempt to describe both the individual motivations for creativity and the influence of group behavior. The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, who suffered from depression, paranoia, and many phobias, said: “My affliction belongs to me and my art—they have become one with me. Without illness and anxiety, I would have been a rudderless ship.” This unfortunate relationship shows us that creativity can be associated with powerful cognitive forces—a dance between a primal, perhaps slightly mad, cognition, and a consciousness that is needed to tame it.

Creativity often requires a combining of two ideas with related functions, such as adding a claw for removing nails to the back of a hammer. It also may require the development of the desired goals or market demand to provide a focus upon the thinking process. This latter notion is reinforced by the American physicist Arthur Schawlow, who claims “the most successful scientists often are not the most talented, but the ones who are just impelled by curiosity…. They’ve got to know what the answer is.” Creativity, when viewed from many perspectives, can be seen as combining two or more ideas, processes, or daydreams. Therefore, the collaborations among people multiply the opportunity to combine ideas.

Creativity often seems to prosper in a collaborative environment. The connection between collaboration and creativity appears to be an innate need. The American psychologist Howard Gruber noted “Creative people must use their skills to devise environments that foster their work. They invent new peer groups appropriate to their projects. Being creative means striking out in new directions and not accepting ready-made relationships…. Each creator therefore invents new forms of collaboration.” According to the American anthropologist Edward T. Hall, “There is a natural drive to collaborate. It may be one of the basic principles of living in substances.”

The interactions of people within a group are an important component of creative expression. Creativity can be nurtured or nullified in a group. While Picasso and Braque collaborated to lead the Cubist movement and Einstein worked with Grossman to develop the mathematical language of nonlinear geometry for expressing relativity theories, many creative people from Sappho to Shakespeare did not collaborate. But how many great creators have had their creative products discarded when their life ended? How many more individuals who, while working within a group, had a wonderful idea attacked or ridiculed so as not to ever be developed? We will never know.

The nature of creativity lies among various psychological and sociological models. While these theories do not predict actions or offer any complete description of creativity, they offer a fragmented foundation for gaining insight. Is creativity an innate talent or something drawn from us by other forces or circumstances? The individual must be creative in order to manage daily challenges, but creativity can arise in spectacular form in the arts and sciences. Creative collaborations can lead to dramatic objects of art and literature as well as powerful changes in human perspective. However, these are forms of creativity that are rewarded and recognized and do not represent the range of human creative expressions. Games with a child or daydreams may express as much creativity as Dante’s Inferno, but it is not recognized in the same light. Moreover, some people never have an opportunity for their creative expressions to find a public forum. Therefore, the individual propensity for creativity in a general sense is impossible to assess.

Sociological models of individual self and its relations to groups indicate people benefit from group participation and identification. The group you identify with can have consequences beyond the functioning of that group—the group can in turn define your self-worth. Moreover, this relationship between self and group can adversely affect your view of those outside your group. Identity theory suggests that when self-proclaimed creative people gather in groups, they will deeply nurture one another’s creativity and at the same time excoriate other groups’ creative efforts. We can see in reviewing historic collaborations of artists and scientists that they gained confidence based on numbers. Therefore, while individual creativity is difficult to appraise, a group culture can have a predictable effect upon the individual members’ creative expression.

What Is Creativity?

Creative action normally has to pass three tests: it must be original, valuable, and require special abilities. Like poetry, creativity often embodies something new and unexpected. Judging a product’s creativity can be based on newness, effectiveness, and the manner in which the problem is solved. These basic categories are referred to as novelty, resolution, and elaboration and synthesis, respectively.

A product with low novelty in reproducing a form might be a chisel, while a product with high novelty might be a 3D printer. This rating would be akin to the low novelty of Norman Rockwell’s art versus the high novelty of Salvador Dali’s art. In the resolution category, a fastener product with low resolution would be a button in contrast to the mechanically complex zipper. This is like comparing blank verse poetry to a structured sonnet. Finally, if elaboration and synthesis were considered for a mathematical machine, an abacus or slide rule would be rated low, while a computer would be rated high.

This rating system has problems in actually attributing creative value, and a high ranking in each of these categories does not necessarily dictate creative superiority. However, these categories provide a helpful language in critiquing designs.

A reflection on what creativity is could be simply anything that provides a delightful surprise.