PRINCIPLE

5

Beliefs Defend Themselves

Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.

—Philip K. Dick

Between 2003 and 2005, researchers conducted a series of studies comparing how Democrats and Republicans interpreted facts about the war in Iraq.1 The researchers were interested in what happens when people encounter new information, especially when it contradicts their existing beliefs.

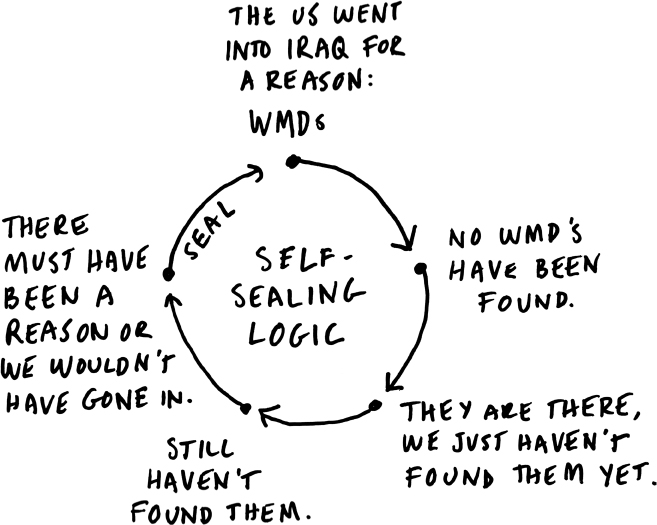

The original invasion was justified in no small part by the Bush administration’s claim that Iraq was concealing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and posed a threat to the United States.

The U.S. did not find any WMDs, and as the war continued, it seemed increasingly unlikely that WMDs would be found.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats challenged these facts. But they had very different interpretations. Democrats concluded that the WMDs had not existed. Republicans concluded that Iraq had moved the WMDs, or destroyed them, or that they had not yet been found. When it became increasingly clear over time that no WMDs would be found, Republican explanations shifted to “Well, there must have been a reason or we wouldn’t have gone in!”

This isn’t just a Republican phenomenon. For the purposes of comparison, the researchers looked at Democrat and Republican attitudes during the 1995 Clinton-led U.S. intervention in the Bosnian conflict and found similar dynamics. They wrote:

“In short, Democrats and Republicans flip when attention shifts from Bosnia to Iraq, as the president responsible for the intervention changes from a Democrat to a Republican. Citizens set aside general partisan values about war and intervention—if any such values exist—to support their party’s position in each conflict.”2

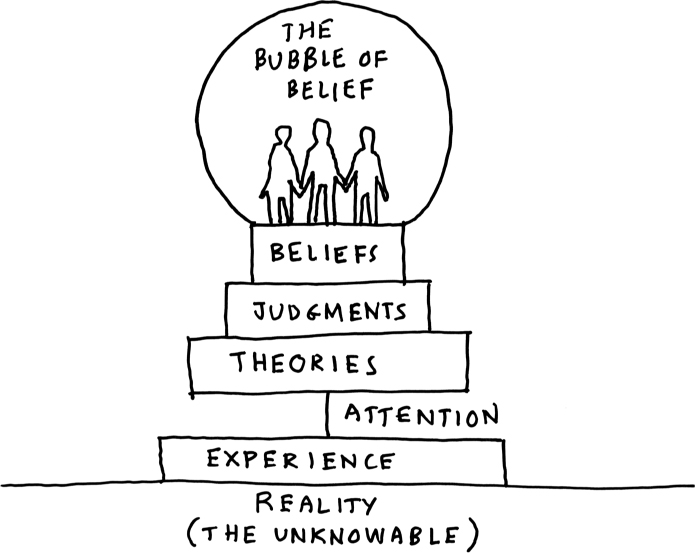

Whatever groups you belong to or most strongly associate with, the dynamics will be similar. Collectively, we create a kind of bubble of belief that reinforces and protects our existing beliefs by denying that alternative beliefs are within the realm of possibility. It’s a kind of collective delusion or dream that we co-create in order to maintain a group map that we use to navigate the world.

It’s a bit like living in a snow globe. If you shake it up, you will get a lot of noise in there as people try to convince themselves that their beliefs are an accurate depiction of reality.

Argyris called this self-sealing logic, or, when applied to organizations, organizational defensive routines.3

In order to maintain a sense of certainty and control, as well as a collective self-image of who we are and what we stand for, we work together to create and maintain this shared map of reality. You probably have more than one shared map that you use to navigate different areas in your life—one that you share with your family, one you share with friends, another one you share with co-workers.

These shared maps are useful because they allow us to do things together, based on shared assumptions. They are also efficient, because they save us from asking questions all the time, so we can get on with our work.

But a shared map also has some dangers, especially when, over time, the map begins to get out of sync with what’s really going on. And the longer a group of people have been operating with a shared map, the more likely there will be a mismatch between the map and reality.

People like stability. Once a group of people has formed a belief, they will tend to reinforce it in a way that creates blind spots to alternative beliefs.

In his book, The Future of Management, Gary Hamel tells the story of a conversation he had with senior auto executives in Detroit.4 He asked them why, after 20 years of benchmarking studies, their company had been unable to catch up to Toyota’s productivity. Here’s what they said:

Twenty years ago, we started sending our young people to Japan to study Toyota. They’d come back and tell us how good Toyota was, and we simply didn’t believe them. We figured they’d dropped a zero somewhere—no one could produce cars with so few defects per vehicle, or with so few labor hours.

It was five years before we acknowledged that Toyota really was beating us in a bunch of critical areas. Over the next five years, we told ourselves that Toyota’s advantages were all cultural. It was all about wa and nemawashi—the uniquely Japanese spirit of cooperation and consultation that Toyota had cultivated with its employees. We were sure that American workers would never put up with these paternalistic practices.

Then, of course, Toyota started building plants in the United States, and they got the same results here they got in Japan—so our cultural excuse went out the window. For the next five years, we focused on Toyota’s manufacturing processes. We studied their use of factory automation, their supplier relationships, just-in-time systems, everything. But despite all our benchmarking, we could never seem to get the same results in our own factories.

It’s only in the last five years that we’ve finally admitted to ourselves that Toyota’s success is based on a wholly different set of principles—about the capabilities of its employees and the responsibilities of its leaders.

I had a similar experience. I was working on a project at Nokia when the iPhone was first announced. I asked a senior executive in the company, “Aren’t you worried about Apple getting into the phone business?”

He said, “No, we’re not worried. They are just going to increase the market for smart phones, and ours is better.”

The company at the time had 40 percent share of the global smart phone market. Today they have less than one percent.

This is self-sealing logic at work. New information from outside the bubble of belief is discounted, or distorted, because it conflicts with the version of reality that exists inside the bubble.

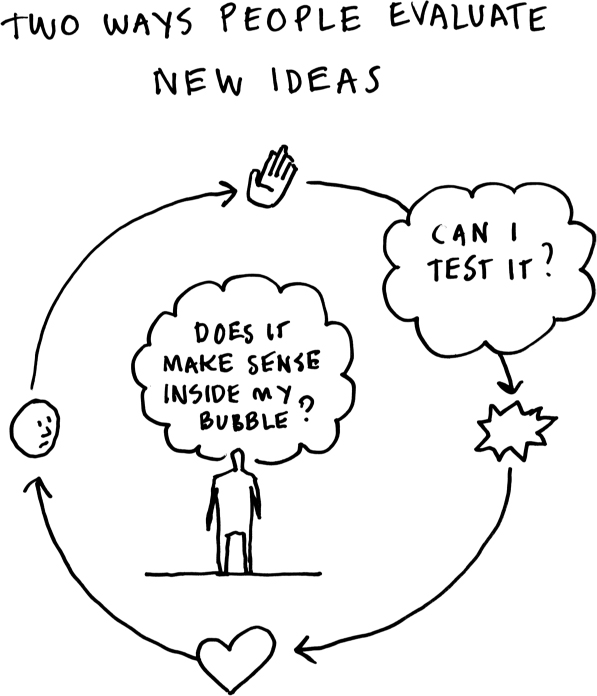

This has to do with the way people evaluate new information. There are two ways that people make sense of new ideas:

• First, is it internally coherent? Does it make sense, given what I already know, and can it be integrated with all of my other beliefs? In other words, does it make sense from within my bubble?

• Second, is it externally valid? Can I test it? If I try it, does it work? This is an excellent way to test a new idea, but one big problem, which causes blind spots and reinforces those self-sealing bubbles, is that people rarely test ideas for external validity when they don’t have internal coherence.

That concept is important enough that I’m going to say it again:

People rarely test ideas for external validity when they don’t have internal coherence.

If it doesn’t make sense from within the bubble, you’re going to think it’s a mistake, or a lie, or somebody got it wrong. You will tend to do whatever is necessary to protect the consistency and coherence of that bubble, because to you, that bubble is reality itself.

Liminal thinking requires a willingness to test and validate new ideas, even when they seem absurd, crazy, or wrong.

PRINCIPLE 5

Beliefs defend themselves.

Beliefs are unconsciously defended by a bubble of self-sealing logic, which maintains them even when they are invalid, to protect personal identity and self-worth.