ONE

Futureback Thinking

About Office Shock

Future Shock, Alvin Toffler’s landmark book,1 made the case that if one major change is happening in your life, you should avoid making any other major changes at the same time—or risk experiencing “future shock.” Toffler argued that individuals, and even societies, could be future shocked if they experienced “too much change in too short a time.”

Toffler was concerned about the dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Age, including technology and office work. Orson Welles, in the movie version of Future Shock that he directed, said:

Our modern technologies have achieved a degree of sophistication beyond our wildest dreams, but this technology has exacted a pretty heavy price. We live in an age of anxiety and a time of stress and with all our sophistication, we are in fact the victims of our own technological strength. We are victims of shock, of future shock.2

Remarkably, Welles said this in 1970 when “modern technologies” were unimpressive compared to what we have now—and crude compared to what we will have ten years from now.

The Shocks Keep Coming

The future shock Toffler was describing grew out of the explosive stresses of the 1960s, including the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the building of the Berlin Wall, May 1968 protests in Paris, the civil rights movement, and the deaths of inspirational figures such as John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.

The shocks still keep coming, reverberating across working and living. The aftershocks of COVID-19 were amplified by global movements seeking social justice, economic equality, and slowing of climate change, including: Black Lives Matter,3 #MeToo,4 Anti-work,5 PeopleNotProfit,6 FridaysForFuture,7 and Scientist Rebellion.8 The groundswell of underrepresented and suppressed people reveals the depth of the social, economic, and health faults the pandemic exposed. Culture wars fume.

Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine9 looked at governmental actions that negatively affected people in war or natural disasters. In 2021, science fiction writer Neal Stephenson published Termination Shock,10 which explored a world so endangered by climate change and governmental inaction that unorthodox solutions were carried out by wealthy private individuals.

During the COVID-19 shutdowns, many people working in offices were shocked by too much change in too short a time regarding where and how they worked. People were stunned by orders to evacuate their office buildings and work from wherever. A cascade of jagged future shocks followed, with second- and third-order consequences. Office work and private life are now intensely entangled, with emotionally mixed consequences. Office shocks were deeply unfair: for some the sudden flexibility was liberating; for others it was awful.

Local governments around the world (with little consistency or coordination) inched at varied rates toward what public health experts call an “interpandemic” or an “endemic” period. As incidence of the virus decreased and impatience increased, there were growing top-down executive orders for workers to return to their office buildings. Many workers, however, refused to go back. Many began searches for new jobs and hybrid ways of working with a new sense of mobility and flexibility.

During the COVID-19 crisis, many organizations were surprisingly productive when people were working from home. Owners of office buildings struggled to make their offices safe and adaptable for new hybrid work arrangements, but the sanitized adaptations were often unsettling and rarely welcoming for a warm-and-friendly reunion. Some returned to ghost offices and quickly went back to work-from-home if they could. Nobody understood what permanent hybrid work at scale could become. Many people did want to return to in-person offices.

Some of the old-fashioned offices that were shuttered during the COVID-19 crisis were the epitome of what is wrong with corporate life. The traditional office itself has many inherent problems, even though it took a global pandemic to shock open executive’s minds to the possibility of better ways of working. Many of the old offices were unfair, uncomfortable, uncreative, and unproductive. Office workers, corporations, and policy makers were shocked into imagining new realities and new options. In some cities, commercial office real estate is a wobbling house of cards.

The old-fashioned office is dead. Office shock is an opportunity to make offices better than they were—and most offices need to be better.

Early Futureback Thinking

In 1901, science fiction writer H. G. Wells sought to forecast “the way things will probably go in this new century.” His aim in writing this nonfiction work was reflected in the title itself: Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life. Later he used the term foresight to describe the systemic study of the future.11 A domain of expertise and practices followed suit, called a variety of names ranging from futures studies to futurology. Accelerated by World War II and enhanced by the emergence of systems science, futures studies became an academic discipline in the mid-1960s. Sociologists like Fred L. Polak,12 philosophers like Marshall McLuhan,13 and environmentalists like Rachel Carson14 anticipated possible futures across social, technological, economic, environmental, and political spheres of human activity.

In 1968, a group of former RAND Corporation researchers with a grant from the Ford Foundation and Arthur Vining Davis Foundation founded the Institute for the Future (IFTF) to take leading-edge research methodologies into the public and business sectors. Since then, IFTF has been committed to building the future by understanding it deeply. IFTF’s mission is to help communities across the globe create stories from the future that provoke insights and actions in the present. For over fifty years, IFTF has applied strategic foresight to help communities develop clarity while avoiding certainty. Many other global communities have contributed to the rise of foresight as a practice, including Singapore,15 the European Union,16 the United Arab Emirates,17 and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.18

Strategic foresight is a powerful way to face the VUCA world: Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous. The VUCA acronym came into being in 1987 at the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.19 The leadership theories of Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus were influential in helping the military to face the uncertainty of what they often called the fog of war. Today’s VUCA world includes the rolling risk of new pandemics, the ongoing challenges of systemic racism, the rich-poor gap (many people cannot afford a decent home office), workers’ increasing concerns about work-life navigation, chronic climate emergencies, and severely degraded trust in institutions.

Foresight enables us to think systemically about VUCA and avoid the techno-optimisim plaguing many people who think technology will solve all our wicked problems.20 As IFTF has argued in its research, foresight enables people and organizations to flip VUCA dilemmas into positive opportunities:

![]() Vision counters Volatility

Vision counters Volatility

![]() Understanding counters Uncertainty

Understanding counters Uncertainty

![]() Clarity counters Complexity

Clarity counters Complexity

![]() Agility counters Ambiguity21

Agility counters Ambiguity21

This approach helps people understand that VUCA is not insurmountable and can be navigated to envision paths to a better future.

VUCA will demand breakthrough ways to “office” for a better future. In the VUCA world, office shock will be an inevitable part of work life, and it won’t be just about the office as a place. It will become increasingly obvious that “office” is both place (an office building or workplace) and a process (officing)—both a noun and a verb. Office shock will be about a lot more than office buildings. Returning to offices won’t be simple, but office shock is a critical opportunity to reimagine where, when, and how “office work” can and should be done in the future.

Think Futureback

Office Shock profoundly blends two concepts: future and back.

Bob Johansen and Mark Johnson, the cofounder with Clayton Christensen of Innosight, have been engaged with each other’s work and started using the term futureback (or future-back) at about the same time.22 Bob and IFTF focus on the long-term future, thinking at least ten years ahead. Mark Johnson and Innosight are strategy consultants, drawing from foresight but emphasizing the present-value of futures thinking.

Thinking futureback—in contrast to present-forward—transforms our thinking and helps us explore alternative futures. This book shows you how to tell futureback stories. Thinking futureback will help you prepare for and navigate future shocks, including office shock.

Surprisingly, it is easier to anticipate directions of change thinking ten years ahead than it is to look out just one or two years. Thinking futureback allows you to sense directions of change—even when the specifics are yet to be determined. Signals that are very specific innovations or events that stretch our thinking about the future can spark thinking futureback. Institute for the Future scans signals globally and studies the emerging patterns of signals that are emerging.

Think Futureback to Reduce Your Cone of Uncertainty

Even though the future is unpredictable, we can do a lot better than just waiting for the future to happen to us. In the introduction we used the example of sensors. Thinking futureback from ten years ahead, it is obvious that sensors will be everywhere, they will be very cheap, many of them will be connected, and some of them will be in our bodies.

To take that example further many people already wear body sensors like smart watches that track biometrics. Ten years from now, most people who want one and can afford it will be wearing a body sensor and many people will have embedded body sensors. Health data from body sensors will be constant and confusing. We’re at the start of a health data gold rush. Like the original California Gold Rush, many people will benefit as this new territory develops, many people will get hurt, and a very few people will discover gold. Looking futureback, the issues—such as privacy, data sensemaking, and equal access to health services for everyone, rich and poor alike—are obvious. The implication of using sensors in other applications, for example, in enhancing knowledge work, is less obvious. The direction of change regarding sensors is clear when you think futureback.

A practical example of the value of futureback is retirement planning. If you are young, it is very difficult to think of yourself as old. People do not tend to be very good at imagining their future selves. If you can think futureback, you can estimate your lifespan and the approximate income you will need as you age. Then, it will be important to consider your sources of income and your strategy for employment and retirement. If you have a traditional job and are planning to retire at age sixty-five, for example, modeling your income needs will be more straightforward than if you are a gig worker or creative artist. As part of a retirement plan, your needs will include mandatory expenses like health care, housing, and food—but your lifestyle choices will make a big difference. Scenario planning can help you play out different lifestyle options under different assumptions. Thinking futureback allows you to see where you need to be and want to be at different stages of your life. Risk tolerance will make a big difference in your choices. The impact of compound interest will be much more visible thinking futureback, even though interest rates are not precisely predictable. Futureback thinking will help prepare you for a better future with financial independence.

An important aspect of retirement planning is deciding where you would like to live as you age. Given the risks of climate change, according to Climate Central,23 flooding is a very likely phenomenon in many parts of the world. Since flooding will influence prices and value of homes, you could check out a futureback map for 2050.24 What will be the flooding risks in areas where you think you might like to retire?25

Even when we look at the forecasts, however, it is very difficult to imagine areas of major cities under water. It is even harder to imagine your own home being flooded. People do not tend to be very good at imagining their future selves. Our colleague Jane McGonigal, in her book Imaginable, describes the difference between thinking futureback based on available forecast data and your personal feelings about places. A data-based forecast of a future with climate change might be: “By 2050, sea levels may rise by as much as 9 feet (2.75 meters) and 750 million people may be displaced.” Your personal forecast of a future with climate change might be something like this: “I’ll be seventy-five years old in 2050. The two airports I use now will both be at risk of flooding. Flying will be less reliable due to extreme weather, so I’ll live near my kids.” You may even want to imagine an innovative solution, such as designing a home with a mechanism to move like a crab to higher ground. Danish architect Bjarke Ingels26 imagined that Manhattan could have a protective green cushion, called the Dryline,27 to protect its coastline from flooding.

Thinking futureback can help you explore different housing options under different assumptions. Risk tolerance will make a big difference in your choices. The possible impacts of climate change will be much more visible thinking futureback. Futureback thinking will help you prepare and be more future-ready.

Futureback is an uncommon common sense today. Ten years from now, thinking futureback will be a survival skill that all successful people will practice. This book will help readers get a head start by teaching your brain new tricks. Thinking futureback is liberating.

In times of great uncertainty, thinking futureback—FUTURE, next, now—is much more revealing than thinking present-forward.

FUTURE, then NEXT, then NOW

Most people today, however, are stuck in linear time: NOW, next, future. Most people are constrained by what some neuroscientists call “The Eternal Now.” Futureback is not the way most people think today. The prefrontal cortex resists thinking futureback, it is focused on protecting you in the present.

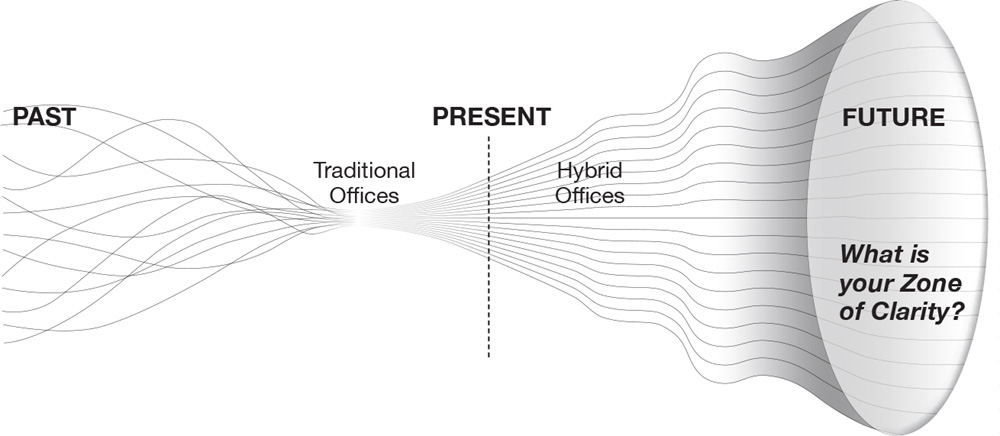

FIGURE 5: The Cone of Uncertainty for Offices. A wide range of choices for offices and officing.

Present-forward thinking is fraught with the urgent details of everyday life—as well as blinders and burdens from the past. Futureback is counterintuitive. Thinking futureback is a challenge of imagination, not of intelligence.

For most adults, especially successful young adults, thinking present-forward is so much of an unexamined assumption that they would never even consider thinking futureback. Thinking back from the future feels off-kilter if you are trapped in the present worrying about pressures like making money, career advancement, paying off mortgages, and child-rearing. The present is so very noisy, so demanding, and so mind-numbing—particularly in chaotic times.

Thinking futureback will help you develop your clarity and moderate your certainty. It is easier to develop clarity when you think futureback—especially in times of crisis. To thrive in the increasingly VUCA world of the future, we will all need to be very clear where we want to go, but very flexible about how we get there. We call this flexive intent, and this is a theme that will continue through the rest of this book.

Our goal is to reduce the cone of uncertainty, help people develop their own zones of clarity while resisting certainty. We can develop clarity by looking futureback, even though we can’t have certainty.

At the present time, the cone of uncertainty, as shown in figure 5, is very wide regarding the future of office buildings and distributed office work. “Return to Office” is a term often used with certainty, but not clarity. The past is known and certain. The present is all-consuming. The future is unknown and filled with uncertainties. Futureback thinking can help narrow the range of uncertainty and help bring clarity. Nobody yet knows what hybrid work will look like in the future. Each worker and each organization will need to develop their own zone of clarity regarding where, when, how, and why they work.

Think Futureback with Stories

Thinking futureback is like a good story—magical, mythic, and fun. Like the outback, the futureback is the mysterious back of the beyond. Like the diamondback rattlesnake, the futureback is dangerous. Like a setback, there will be pathways forward that fail, but provide learning experiences. If you aren’t at least a little frightened by the future, you’re not paying attention. Thinking futureback allows you to sense directions of change and prepare—even when the specifics are impossible to predict.

Our brains look into the future automatically to protect us from what might be coming next.28 The hippocampus contributes to creating visions by using past information to construct the scene of a possible future event. The power of stories lies in breaking free of our prefrontal cortex (the locus of logical thinking), to refocus our attention on what is beyond.29 Recent research on the neuroscience of storytelling has concluded that our brains are wired for stories and, if we do not hear stories, we make them up.30

Stories help us make some sense out of what’s going on around us. They help us to connect with others, either reconstructing the past or imagining a future, using verbal and visual language capabilities. We fill these mental-made worlds with the fictional narratives we call identities. Games are enacted stories. We play games of aspiration, decision, action, and learning that expand our connections with new stories.

A good story is unforgettable when it provokes the brain’s neurotransmitters. Storyteller David Philips31 describes a good story as offering listeners a neurochemical cocktail: endorphins are secreted when people laugh, characters that create empathy and trust release oxytocin, and a dopamine rush is experienced by piquing curiosity with problems and suspense, rather than the exhilaration of resolution.32

Consider this brief story: Go is perhaps the most complex game ever designed by humans, the oldest continuously played board game, and the biggest challenge for AI competitions with humans. In 2016, the DeepMind program AlphaGo defeated legendary human Go player Lee Sodel, who said afterward that “this experience made me grow. . . . I found my reason to play Go.”33 When a computer program defeated a human Go player, it wasn’t the end of the Go game (in fact, global sales went up), it was the beginning of new ways to play Go. Augmented humans now play Go, and they play it differently than before. This story animates the facts, brings them to life, and makes them more memorable.

Stories can take many forms, including visual. For example, as more data are available about us, about what we eat, who we interact with, what we say, how we feel, our stories of self will take on new significance. In the future, cheap sensors will be everywhere, including inside our bodies, and they will generate lots of data. As this health data gold rush increases,34 we will be able to make stories about ourselves come true by manipulating how we eat, work, and play.

Will Storr believes “we are all story makers.”35 A 2020 MIT Technology Review cover story introduces readers to the next generation’s stories of multiple selves. By using technology to describe, reveal, expand, and sometimes mask identities, a new generation is expressing itself in ways not part of the traditional office.36 Future projections of the self, based on data from the present, open new paths to explore identity in more meaningful ways.37 Cross-generational communication is so important right now, since the officeverse will be created largely by young people—some of whom are not even in the workforce yet.

Stories and their accompanying neural networks correspond loosely to the ways we absorb, manipulate, and socialize information. This helps us step away from focusing on an individual’s intelligence to an individual’s interactions with others.38

Anthropologists believe storytelling to be one of the primary reasons Homo sapiens survived over other species.39 Sharing stories is powerful because it synchronizes the brain activity of the teller and the listener.40 The stronger the synchronization, the better the understanding between people.41 Storymaking—the co-creation of a shared story—amplifies synchronization and mobilizes people for change.42

Our practice of worldbuilding extends the boundaries of experience with characteristics such as history, geography, and even ecology.43 Worldbuilding establishes boundaries with characteristics such as history, geography, and ecology. These worlds enable listeners to fill in the details, making the story a shared experience.

Futureback Thinking Requires a Full-Spectrum Mindset

This is no time to lock yourself into any fixed way of thinking, or any fixed strategy about offices.

The office shock provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic was just the first of many related shocks to come. This is the beginning of a major cycle of change in the ways we organize work and labor, and ultimately our lives. The traditional office is a social and physical technology that no longer works for many people. We cannot go back to the office the way it was, and the path forward is not at all clear.

Thinking futureback requires a full-spectrum mindset:44 the ability to seek patterns and clarity across gradients of possibility, outside, across, beyond traditional boxed categories, or maybe even without any boxes or categories, while resisting false certainty. It helps us find the multidimensional ways in which things are connected—not just the ways in which they are distinct from each other. To think and act across gradients of possibility is to avoid simplistic categorizations or false certainty. We need to look beyond binary choices. In this book, we apply full-spectrum thinking to the future of offices and officing by identifying spectrums of choices that must be made in the present to start charting the paths to the future.

At the core of a full-spectrum mindset are both the ancient traditions and latest neuroscience findings that encourage humans to find balance and navigate life’s ambiguities. In a real sense, human life has always been a VUCA world, beginning with the fact that we all must die. This universal message is central to the teachings of the Tao, concepts of heaven and earth, and even “The Force” in the Star Wars movies. It is also reinforced by scientific understanding of homeostasis for any biological system. Humans maintain optimal stability for survival by adjusting our internal chemistry according to external conditions. Full-spectrum thinking seeks a balance between the dichotomies of life: alone and together, giving and taking, surviving and providing. A full-spectrum mindset aims to empower us to find the balance necessary for creating better futures for working and living.

In these times of great uncertainty, thinking futureback and with a full-spectrum mindset is much more revealing about the future than staying stuck in present-forward mode. African American writer and activist James Baldwin added a cautionary note:

Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.45

Your Choices about Futureback Thinking

Strategic foresight using futureback thinking with a full-spectrum mindset will help you write your own stories of offices and officing:

1. How can you break out of thinking present-forward, reduce your own cone of uncertainty, and move toward the futureback thinking of Future-Next-Now?

2. Full-spectrum thinking requires breaking out of the ingrained patterns of categorizing things into familiar boxes. How might you grow your full-spectrum mindset?

3. How can you develop and practice your storymaking skills?